Abstract

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are driving a shift toward energy-efficient illumination. Nonetheless, modifying the emission intensities, colors and directionalities of LEDs in specific ways remains a challenge often tackled by incorporating secondary optical components. Metallic nanostructures supporting plasmonic resonances are an interesting alternative to this approach due to their strong light–matter interaction, which facilitates control over light emission without requiring external secondary optical components. This review discusses new methods that enhance the efficiencies of LEDs using nanostructured metals. This is an emerging field that incorporates physics, materials science, device technology and industry. First, we provide a general overview of state-of-the-art LED lighting, discussing the main characteristics required of both quantum wells and color converters to efficiently generate white light. Then, we discuss the main challenges in this field as well as the potential of metallic nanostructures to circumvent them. We review several of the most relevant demonstrations of LEDs in combination with metallic nanostructures, which have resulted in light-emitting devices with improved performance. We also highlight a few recent studies in applied plasmonics that, although exploratory and eminently fundamental, may lead to new solutions in illumination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

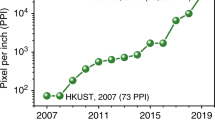

Solid-state lighting (SSL) is an illumination technology that has emerged in the past decade due to the development of white light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Currently, LEDs use a mature technology that can outperform traditional light sources due to their higher efficiencies, longer lifetimes, fast switching, robustness and compact size1, 2. The working principle of LEDs is based on electroluminescence, that is, the radiative recombination of injected electron–hole pairs in a material. Electroluminescence in inorganic semiconductors was first observed by Round3, who applied a voltage across two contacts on a SiC crystal to generate yellow light. Electroluminescence was intensely investigated in subsequent years4 and was reported in several III–V semiconductors in the 1950s5, 6. Techniques to create p–n junctions also improved, leading to the demonstration of infrared and red LED emission in GaAs and GaAsP in 19627, 8. Although blue LED emission turned out to be more complex than initially thought, due to difficulties associated with producing high-quality GaN and doping this material, it was finally accomplished in the early 1990s by two independent research groups9, 10, 11. This achievement represented a technological breakthrough that led to the award, in 2014, of the Nobel Prize in Physics to Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura. We expect to see widespread replacement of traditional light sources with LEDs within the next two decades, leading to a considerable reduction in worldwide electricity consumption. To facilitate this transition, we must integrate LEDs into many different applications. To do this, we must be able to accurately and specifically control brightness, color and directionality of light emitted from LEDs. It appears that this control may be achieved using nanostructures12.

Nanostructures, which have dimensions comparable to the wavelength of light, are especially suited to enhancing light–matter interactions13. Metallic surfaces and nanostructures supporting surface plasmon polariton (SPP) resonances are of particular interest in this regard14. These resonances have their origin in the coherent oscillation of charge carriers in the metal. The spontaneous emission from sources in the proximity of metals can be modified by SPPs, thereby influencing the emission rate and directionality15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. These modifications are analogous to the resonant amplification and directional radiation of antennas. Therefore, metallic nanoparticles supporting SPPs have been referred to as optical antennas or nanoantennas35, 36. However, integrating such resonant nanostructures into state-of-the-art lighting applications remains challenging. The vast majority of studies has focused on modification of the emission properties of single and/or low-efficiency emitters23, 37, 38, while real applications in SSL require modification of emission over macroscopic areas, typically in the mm2 range, of highly efficient emitters for which the typical photoluminescence quantum yield (QY) exceeds 90%. Until recently, these stringent requirements have limited the use of plasmonic structures for SSL. This situation is quickly changing due to the introduction of cost-effective nanofabrication techniques for use in light extraction, spectral shaping of emissions and strong beaming, without requiring additional external optical components37, 39, 40, 41, 42. This article reviews recent developments regarding nanostructured metallic surfaces and nanoantennas for use in SSL, an emerging field that provides new opportunities for plasmonics applications.

Solid-state white-light generation

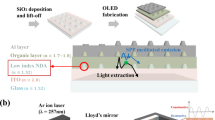

Organic LEDs43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 and light-emitting electrochemical cells51, 52 are lightweight, flat and thin large-area diffuse light sources that represent new illumination technologies. However, inorganic LEDs are currently best suited for general illumination purposes53. Therefore, the following discussion focuses on inorganic LEDs. There are two generic approaches to generating artificial white light using inorganic semiconductor LEDs54, 55, 56. In the first, several LEDs emit different colors that are combined to produce white light57. Although significant advances have been made in the development of nanoscale LEDs58, 59, 60, 61, 62, the maximum efficiency of all semiconductor-based white LEDs is limited by the relatively low efficiencies of green and yellow LEDs, a challenge referred to as the green–yellow gap. In the second and currently the most prevailing approach, highly efficient blue LEDs are used to generate green and red light via color conversion using one or more photoluminescent materials, traditionally called phosphors63, 64, 65. This second approach is illustrated in Figure 1. The phosphor must have the following: (i) a close-to-one QY to maximize blue-to-green/red conversion efficiency; (ii) excellent temperature and chemical stabilities; (iii) moderate thermal quenching of emissions at temperatures over 100 °C; (iv) an absorption spectrum that overlaps with the blue LED emission spectrum; (v) a large absorption cross section; and (vi) an emission spectrum that leads to high-quality white-light emission. Therefore, one of the greatest remaining challenges in SSL is the difficulty associated with simultaneously tuning the chemical, structural and optical characteristics of the phosphor material that fulfills the above requirements. This challenge has become the subject of extensive research in materials science66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73.

Currently, the leading commercial methodology for obtaining white light using phosphors, so-called phosphor-converted LEDs (pcLEDs), uses yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG, Y3Al5O12) doped with Ce3+ rare-earth ions (YAG:Ce) as the phosphor. Phosphors based on rare-earth ions have low absorption coefficients in the blue region, resulting in the need for a relatively large amount of material (the typical thickness of such phosphors is on the order of several tens of microns). Such phosphor layers incorporate randomly positioned light scatterers that maximize light extraction74, 75, 76, albeit with a Lambertian angular profile. Moreover, approximately half of the converted light exits the phosphor layer in the backward direction, that is, toward the blue LED. For these reasons, additional optical elements, such as mirrors or scattering materials, are incorporated into the device to maximize light output.

Efficiency of LEDs

In general terms, the efficiency of a light-emitting device is the product of three partial efficiencies:

ηexc is the excitation efficiency. In the case of electrically driven devices, it represents the fraction of injected carriers that recombine in the active region. In the case of optically pumped devices, it accounts for the absorption efficiency of the phosphor. ηrad is the radiative efficiency, often referred to as the internal quantum efficiency or QY. It represents the fraction of the excited or injected electron–hole pairs that recombine to emit a photon, and it is defined as the ratio of the radiative rate to the total recombination rate. The last factor in Equation (1) is the extraction efficiency ηext, which is the fraction of blue/green/red light that escapes the device into free space. Because emitted light can be trapped within the device (via total internal reflection) and eventually absorbed, many light-emitting devices rely on the integration of light-extracting structures to increase ηext. In addition to efficiency, other parameters defining the color of the emission must be assessed when developing new LEDs77.

Metals and light emission

Recently, various arrangements of metallic nanostructures have been proposed as a means of controlling light emission15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33. Research efforts in nanophotonics have mainly focused on using nanostructures to improve ηrad via modification of the local density of optical states to which an emitter can decay15, 78. For low-QY emitters (for example, QY<0.3), this approach leads to a significantly brighter source. However, emitters with QY ca. 100% are readily available for use in SSL. Therefore, enhancing the QY of poor emitters is not necessary for SSL applications. In fact, metallic nanostructures may reduce the overall efficiency of phosphor-based devices. Where metallic nanostructures benefit emission wavelength is in extracting specific emission colors in defined directions, thereby controlling the angular and spectral distributions of emitted light without diminishing significantly the device efficiency. Regarding ηexc, optical losses occurring at the excitation wavelength associated with the permittivity of metals are expected to be among the main limitations with regard to the overall efficiencies of plasmonic pcLEDs. A recent article addresses the role of metal absorption in the external QY of emitters coupled to arrays of plasmonic nanoparticles. It concludes that due to the reduced fraction of light absorbed by the metal nanoparticles control of the illumination conditions of the arrays can provide significant QY enhancement79.

SPPs are surface waves at the interface between a metal and a dielectric that are characterized by the manner in which they propagate along the surface while decaying evanescently away from it. These characteristics depend on the permittivities of the metal and the dielectric. SPPs result from the coherent oscillations, driven by the electromagnetic field, of the charge carriers in the metal. Emissions from sources in proximity to a metallic layer are strongly modified via the excitation of SPPs, which can be coupled to free space radiation by structuring the metal surface. A number of calculations describing the SPP modification of exciton decay rates have been reported40, 80, 81, 82, 83. As illustrated in Figure 2, SPP-coupled emission can be described according to a simple model based on coupling rates, in which the transfer of energy from the emitter to the plasmon modes occurs, followed by the radiative coupling of the plasmon modes into radiation. As discussed in the next section, this coupling has been used to improve the emission of LEDs. Complementary to metal layers are metal nanostructures that support localized optical resonances known as localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs). The LSPR frequency and linewidth depend on the geometry and size of the nanoparticles84, the permittivity of the metal and the surrounding medium. For emitters in close proximity to metallic nanoparticles, the fluorescence can be modified via processes occurring at the excitation and/or the emission wavelengths15, 17, thereby involving all three terms in Equation (1). In addition, fluorescence enhancement depends strongly on the QY of the emitter81, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90. Indeed, for high-QY emitters distributed over large areas, very little improvement of the QY can be obtained when using nanostructures that only modify the emissions of highly localized sources in their proximity80. Nevertheless, the directionality of the emission of a localized source coupled to a resonant metal nanoparticle can be modified as illustrated in Figure 3a.

Sketch of the surface plasmon-coupled emission. It illustrates the coupling of an emitter into a SPP with the subsequent coupling of the energy of this plasmon mode into the radiation continuum. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 82. Copyright 2008 Optical Society of America.

(a) Sketch of the interaction between a light emitter and an optical antenna. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 25. Copyright 2009 Optical Society of America. Side view of the simulated spatial field distribution in three unit cells of the array at a frequency corresponding to (b) a localized surface plasmon resonance and (c) a collective resonance33.

Individual nanoantennas may be used to modify the emission of quantum wells, but they are not an option for influencing the emission of the much thicker phosphor layers. To circumvent this limitation, nanoparticles can be arranged in periodic arrays, such that their optical response is reinforced through coherent scattering. This leads to a collective plasmonic–photonic resonance first described by Carron et al.91. and Markel92 in the context of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Schatz and co-workers later revived interest in this collective resonance phenomenon via a series of theoretical papers that demonstrate the emergence of very sharp resonances (ca. 1-meV linewidth) in the extinction spectra of arrays composed of metal nanoparticles93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103. Such sharp resonances signify the extremely low radiation losses that collective resonances feature. In-plane scattering by the nanoparticles and phase accumulation of these scattered fields govern the optical response of the array104. Periodic arrays in homogeneous dielectrics are characterized by narrow resonances called surface lattice resonances (SLRs). Interestingly, SLRs with linewidths as narrow as ca. 8 meV have been obtained experimentally using carefully designed periodic arrangements of gold nanorods103. These comprise the sharpest plasmonic resonances ever reported, reaching values close to those theoretically predicted by Schatz, which are the limit of meaningful expectations for lighting applications. In addition, if an optical waveguide is placed near the array, waveguide-plasmon polaritons can be excited105, 106, 107. In the case of SLRs, the nanoparticles interact with Rayleigh anomalies, which are the onset of diffraction orders, that is, the frequency at which diffraction orders propagate in the plane of the array. This in-plane diffraction enhances the radiative coupling between the individual nanoparticles, giving rise to a collective resonance. For waveguide-plasmon polaritons, this radiative coupling between nanoparticles is enhanced by guided modes in high-refractive index layers108. In the particular case of light emission, emitters in the proximity of an array can decay into either of these collective resonances and consequently radiate into free space with a spectrum and directionality determined by the dispersion of these collective modes107, 108.

Figure 3b and 3c illustrates the electromagnetic field enhancements characteristic of two distinct resonances in a periodic array of metal nanoparticles. Figure 3b represents a cross section at the LSPR condition. Associated with the LSPRs is a large electromagnetic field enhancement that is highly localized to the individual particles, as seen near the base of the nanostructures in Figure 3b. In contrast, Figure 3c shows a collective resonance where the field is enhanced over a much larger volume. These extended field enhancements enable circumvention of the limitations regarding critical placement of the emitter relative to the metal nanoparticles109. Moreover, the emission from such an extended state can be highly directional110, 111, as shown below. These are the key advantages of using collective resonances for modifying the emission of phosphor layers33. The metallic nanoparticle array behaves as a phased array of optical antennas, with the relative phases between antennas determined by their resonant responses and separations. The radiation patterns of subwavelength sources are modified by coherent scattering within the periodically spaced metal nanoparticles112.

It is noteworthy that although this review focuses on the impact of metallic nanostructures on the performance of light-emitting devices, metallic and dielectric nanostructures represent complementary approaches to modifying the emission properties of light sources. Several reviews that discuss modification of the emission characteristics of LEDs using dielectric materials have been reported in the past few years113, 114, 115. In particular, wavelength-sized dielectric structures have demonstrated improved light extraction116, 117, 118, and accurate control of radiation patterns119 and polarizations120. A recent report demonstrated that the effects of periodic arrays of Si nanoparticles on the performance of thin layers of emitters are similar to those of their plasmonic counterparts121. Choosing between metals and dielectrics for enhancement of light emission will depend on fabrication constraints and/or the limitations associated with the particular goal.

Plasmonic-based light emission enhancement

Plasmon-enhanced emission from quantum wells

In this section we focus on the different nanophotonics-based approaches that have been used to improve the efficiencies of inorganic semiconductor LEDs. Inorganic blue LEDs that are based on InGaN/GaN multi-quantum-well heterostructures are currently used in advanced architectures to obtain white-light emission. However, light generated in the active region of the multi-quantum-well structure can be reflected at the interfaces and trapped in the layered structure before it reaches the phosphor. To remedy this and maximize light extraction, metallic surfaces and nanostructures have been used.

The metallic thin films used with SPPs have been applied directly to LEDs to enhance the spontaneous emission rate of excitons in quantum wells and, therefore, the QY37, 39, 40, 41, 122, 123, 124. The process can be explained as follows. Electron–hole pairs are injected in the active region of the LED. When a metal layer is grown at a distance smaller than the evanescent decay length of the SPPs, the electron–hole pairs recombine, giving their energy to the SPPs. Thus, the metal provides additional states for exciton recombination125. This enhanced density of states for exciton recombination can significantly increase the recombination rate. Because SPPs are evanescent surface waves, they cannot radiate to free space. The metallic surface can be made rough to efficiently couple SPPs to free space radiation and enhance the emission intensity. To illustrate this effect, Figure 4a shows the photoluminescence intensity spectrum for different metal layers deposited over the blue LED at a distance of 10 nm. Enhancement of the visible light emission originates from a combined higher recombination rate and a higher quantum-well extraction efficiency enabled by the nanometer-sized roughness in the metal layer. Although such random textures result in improved extraction efficiencies, they provide little control over the directionality of the emitted light, which typically displays a Lambertian profile127.

(a) Photoluminescence spectra of blue LEDs coated with Ag, Al and Au. The enhanced emission of the coated LEDs is due to the outcoupling of SPPs with the roughness of the metal to far-field radiation. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd122, copyright 2004. (b) Far-field radiation patterns of blue LEDs that feature a one-dimensional grating (red solid curve) and triangular nanoantennas (black dotted curve), compared with those of the bare LED sample (blue dashed–dotted curve) and a flat metallic coating (green dashed curve). Reprinted with permission from Ref. 126. Copyright 2013, AIP Publishing LLC.

Accurate control over the angular distribution of the emission can be achieved using metallic nanostructures, which are directly fabricated, with predetermined geometries and dimensions, on the emissive semiconductor surface80, 128, 129, 130. Aperiodic designs may also be used to avoid undesirable angular and/or spectral dependencies131. Unidirectional beaming of the LED emission has been recently demonstrated using a periodic array of optical antennas with specifically designed geometries126. Figure 4b shows the far-field radiation pattern of such a nanostructured blue LED. In the absence of the metallic nanostructure, a broad Lambertian emission is observed (blue dashed dotted curve). The silver flat film causes a substantial reduction in the intensity of the emitted light for both polarizations (green dashed curve), because no mechanism is provided to scatter the excited SPPs into radiation. In contrast, in the direction of the maximum intensity for one polarization, the output intensity of the LED with metallic nanostructures (black dotted and red solid curves) is enhanced compared with that of the flat sample. This polarization dependence can be attributed to the asymmetric shape of the nanostructures. Emission enhancements with a preferential light polarization can be beneficial for applications where light impinges upon smooth surfaces at nearly grazing angles, for example, automotive lighting. In these cases, it may be desirable to selectively enhance the emission obtained for one polarization only, because the other polarization may lead to unwanted effects, such as glare from incoming drivers.

Plasmon-enhanced emission from phosphor layers

We now turn our attention to emission modifications obtained using extended emitting layers. Phosphor layers are typically much thicker than quantum wells. The potential of metallic nanoparticle arrays to modify the Lambertian emission from such thick luminescent layers has been demonstrated in several reports24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 42, 108, 132, 133. This section provides few examples of how these arrays modify the emissions of layers of emitters. In contrast to LSPRs, which are usually characterized by their broadband responses and weak angular dependence, collective plasmonic–photonic resonances in antenna arrays can be spectrally very narrow and exhibit strong angular dependence.

Vecchi et al.24 first demonstrated the use of collective plasmonic resonances to modify the emission of luminescence layers, using near-infrared-emitting dye molecules and arrays of gold nanoparticles. Lozano et al.33 proposed that these systems be applied to SSL by using highly efficient visible-light-emitting dye molecules as extended phosphor layers and arrays of aluminum nanoparticles. In this work, a sample such as the one shown in Figure 5a was used to enhance the emission of a 700-nm-thick phosphor layer consisting of a high-QY and a photo-stable dye by more than a factor of 60 at certain wavelengths and in defined directions. This enhancement is illustrated in Figure 5b and 5c for normal incidence, where the extinction and photoluminescence enhancement (PLE) spectra are displayed, respectively. The latter is given by the ratio of the emission from the dye layer with and without the nanoantenna array. The enhanced directional emission can be described as follows. The photo-excited dye molecules relax, exciting collective resonances in the particle array. The periodic structure of the array is responsible for the directional outcoupling of the emission in defined directions. The narrow linewidths of the emission associated with the collective modes are a direct consequence of the enhancement of the spatial coherence of the emission due to the coherent scattering by the nanoantennas. The 60-factor fluorescence enhancement of Ref. 33 can be attributed to a ca. 6-fold enhancement of the excitation efficiency (ηexc) and a ca. 10-fold enhancement of the extraction efficiency (ηext). Moreover, based on time-resolved measurements, only a very small modification of the QY was determined (ca. 15% degradation at most). A visualization of this enhanced emission is shown in Figure 5d, which is a photograph of the emission of a phosphor layer on top of a nanoantenna array (right side). For direct comparison, a reference sample consisting of the phosphor layer with the same thickness but without the antenna array is also shown (left side).

(a) Scanning electron micrograph of a square array of aluminum nanoparticles. The inset is a sketch of a metal nanoparticle array pcLED, where the phosphor layer is represented by the transparent red layer. (b) Extinction and (c) PLE of an aluminum nanoparticle array covered by a thin phosphor layer. Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd33, copyright 2013. (d) Photograph of the emission of a standard pcLED (left) and a pcLED that exhibits enhanced emission due to the integration of a hexagonal array of metal nanoparticles (right). (e) Fourier image of the unpolarized red emission (610–620 nm) of an unstructured pcLED. (f–h) Fourier images of the unpolarized red emission of a similar pcLED that features a hexagonal array of Al nanoparticles with lattice constants (f) 475 nm, (g) 425 nm and (h) 375 nm. Reproduced from Ref. 42 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The directionality of this emission enhancement can be controlled depending on the application. Figure 5e–5h highlights recent results demonstrating tailored enhanced directional emission in narrow angular ranges for red light (λ=620 nm) with hexagonal arrays of nanoantennas42. This spectral region is of particular interest with regard to achieving warm white light in SSL applications. High symmetry lattices, such as the hexagonal array, facilitate a more homogeneous distribution of the emission over the azimuthal angle, as shown in the photoluminescence intensity polar plot measurements displayed in Figure 5e–5h. Manipulating the separation distance between aluminum particles enables accurate control over the directionality of the red emitted light in pcLEDs42.

The inclusion of metallic nanoparticles minimizes the need for optical components in LEDs, such as parabolic mirrors or condenser lenses that are used for beaming the emission. These optical elements are often bulky, increasing the total size of the LEDs and limiting their integration. Therefore, the performance of metallic nanoparticle arrays in SSL applications must be assessed in terms of overall system efficiency with and without the presence of the metallic nanoparticle arrays. From a device perspective, the enhancement of phosphor-layer emissions enabled by the use of nanoparticles must not only be compared with emissions obtained from the same layer when no nanoparticles are used. We must also compare the results obtained with the same phosphor layer under conditions in which the usual secondary optical elements are in place.

An additional advantage of nanoantenna-enhanced emission is that it also reduces the phosphor-layer thickness, which is important with regard to heat dissipation. Heat reduces emission efficiency, limiting the performance of LEDs. So far, it has not been easy to use thin layers in pcLEDs owing to their low blue absorption; the conversion efficiencies of these layers have not been sufficient to generate the desired emission spectrum. Therefore, the combination of metallic arrays and new phosphors, such as dye molecules or quantum dots, enables the use of layers that are much thinner than standard YAG:Ce pallets, resulting in improved heat management and high extraction efficiencies.

Outlook and conclusions

LEDs constitute a new technology that is currently driving substantial changes in the way artificial light is generated. Metallic nanostructures enable strong light–matter interactions that facilitate unprecedented improvements in the emission intensities, colors and directionalities of light sources positioned nearby. This review presents and discusses new methods for enhancing the efficiency of LEDs using metals structured on the nanometer scale. We have provided a general overview of state-of-the-art LED lighting, discussing the main requirements of both quantum wells and phosphors for efficient generation of white light. We also discuss the main challenges facing researchers in this regard and the potential of plasmonics to overcome them. In what follows, we highlight a few recent findings in plasmonics that may lead to new illumination solutions and provide perspectives for future progress.

Several applications, for example, screen or automotive lighting, require light to be directed in only one direction. For planar structures, such as shallow nanoantenna arrays, light beaming into small angles is enhanced with roughly equal strengths in the forward and backward directions. The light emitted backward must be recycled using secondary optics, resulting in losses. To address this issue, the forward–backward light emission symmetry of planar structures can be broken by integrating an array of nanostructures with a pyramidal shape into the fluorescent layer134. Figure 6 shows the PLE spectrum of an aluminum nanopyramid array. Notice that the PLE differs toward the top (black curve) and bottom (red curve) of the nanopyramids. At the LSPR wavelength (~650 nm), the nanopyramid array beams more light toward the bottom of the pyramids. The opposite occurs at the SLR wavelength (~585 nm). These effects are due to the enhanced magnetoelectric response of the nanopyramid array (magnetic dipole moments are excited via the electric field of light), which originates from the pyramidal shape and height of the nanostructures134. Future research should further investigate these phenomena in order to increase emission asymmetry and maximize the fraction of the emitted intensity that can be efficiently used in SSL.

PLE toward the top (black curve) and bottom (red curve) of the pyramids. The inset displays a scanning electron micrograph of the fabricated structures before the deposition of the luminescent layer. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 134. Copyright 2014, American Physical Society.

Beyond passive spectral and directional control of light emission, a long-standing goal in nanophotonics is to actively control emitted light properties by means of an external tuning parameter. This can be achieved by incorporating materials with optical properties that depend on applied voltages, heat, strain or illumination profiles135, 136, 137, 138. Liquid crystals are particularly interesting in this regard. Their tunable orientations have been used to actively control the properties of LSPRs and SPPs139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145. Active light emission from antenna arrays has recently been demonstrated with liquid crystals146. Further research in this regard is sure to attain active control of the color, direction, polarization and intensity of emission from pcLEDs.

Thus far, the examples of spontaneous emission modifications of light emitters coupled to plasmonic resonances provided in this review involve the so-called weak coupling regime. Recently, strong coupling has attracted more attention. Strong coupling is characterized by an emitter–resonator energy exchange rate that exceeds all loss rates. The energy exchange rate between an ensemble of emitters, such as those found in macroscopic light-emitting devices, and an optical mode depends on the concentrations of the emitters. When the collective oscillator strength of the ensemble of emitters becomes comparable to that of the optical mode, that is, at high densities of emitters, mixed light–matter states known as polaritons can be created. Strong coupling between emitters and SPPs has been investigated with regard to propagating modes in flat147, 148, 149 and perforated150, 151, 152 metallic layers, as well as creating localized modes in nanostructures153, 154, 155, 156. Recently, strong coupling between SLRs and emitters has also been observed157, 158, 159. Törma and Barnes160 have recently published a review article in this emerging field. Although the physics of strongly coupled plasmon-emitter systems is very rich, and the prospect of strongly interacting emitters is exciting, the potential of these systems for use in light-emitting devices has rarely been discussed. One of the challenges in this regard is related to the poor QY that phosphor layers with high densities of organic molecules display. Although it is required to access the strong coupling regime, a high molecular density degrades the QY of the ensemble via an effect known as ‘concentration quenching’161. Therefore, challenges remain with regard to improving high-QY light-emitting devices via strong emitter–plasmon coupling.

Laser diodes are being considered as an alternative to LEDs for future SSL applications to circumvent the strong reduction of ηrad that blue LEDs experience at high current densities. This issue, called the efficiency droop162, 163, 164, is one of the biggest challenges with regard to utilizing blue-light-emitting materials and devices for SSL165. Photonic band-edge lasers have been extensively investigated during the past two decades166, 167, 168, 169. Plasmonic nanolasers provide faster dynamics and offer the opportunity to realize ultracompact devices at the expense of beam directionality170. Diffractive plasmon lattices overcome this limitation32, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175. Figure 7a displays the lasing threshold curve for an Au particle array combined with a dye-doped polymer acting as a gain medium32. Figure 7b and 7c shows the Fourier images of the emissions below and above threshold for an array made of Ag nanoparticles, respectively, illustrating the highly directional nature of the lasing mode. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the lasing modes in these sorts of arrays can be modified with liquids of different indexes of refraction, as illustrated in Figure 7d175.

(a) Emission spectra as a function of the pump power for a plasmonic array laser. The inset shows the output emission intensity as a function of the input pump pulse energy. Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd32, copyright 2013. (b,c) Fourier images below and just above threshold for an array with a lattice constant of 380 nm. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 174. Copyright 2014, American Physical Society. (d) Lasing emission from Au arrays embedded in different refractive index environments. Reprinted from Ref. 175, Macmillan Publishers Ltd, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

In conclusion, we have reviewed different metallic nanostructures that provide new possibilities for efficient light management in the next generation of LED devices. A central goal of SSL technology is to replace all incandescent light bulbs worldwide. Consequently, efficiency and cost are currently driving the market. Solutions implying an increase in the overall cost of the lighting device are currently not viable for general lighting purposes. However, this situation will change if the market becomes design- or performance-driven or once the first generation of LED luminaires becomes obsolete. Such a paradigm shift will open the door to the integration of cost-effective nanophotonic structures, which will in turn enable realization of more compact devices with fine control over the intensity, directionality and color quality of the resulting emitted light. Several parameters are typically used to assess the performance of LED-based lighting, that is, quantum efficiency, luminous efficacy, correlated color temperature and color-rendering index (CRI), and maximizing all of them simultaneously is unfeasible. Indeed, there exists a clear trade-off between luminous efficacy and light quality. White-light sources require an emission spectrum that extends throughout the visible range, thereby significantly reducing their maximum luminous efficacy (which is attained for a light source that converts 100% of its electrical power into green radiation, to which the human eye is most sensitive). A wide variety of applications can benefit from LED devices that integrate different emission characteristics. In particular, for general illumination applications, the light source must show a high correlated color temperature as well as a CRI of at least 90 and a uniform color-over-angle. Even higher CRI values, that is, toward 100, are required in museums or in retail businesses. In contrast, highly directional sources are sought for automotive lighting, where the compactness and the freedom to design the esthetics of the light source are more important than the efficiency or quality of the emitted light. Finally, directional narrowband sources are needed in the light guides used in screens. Metallic nanostructures offer new opportunities for tailoring the emission spectra of luminescent materials that compose emitting devices as well as associated angular dependence. Such fine emission control, as illustrated by the different approaches highlighted in this review, should certainly improve the performances of devices designed to for the aforementioned applications. The overall benefit of nanostructures is, in many cases, still limited due to increased complexities in device fabrication. Nonetheless, tuning light emission in LEDs continues to be a key challenge of fundamentally interest and technological relevance.

References

Schubert EF, Kim JK . Solid-state light sources getting smart. Science 2005; 308: 1274–1278.

Tsao JY, Crawford MH, Coltrin ME, Fisher AJ, Koleske DD et al. Toward smart and ultra-efficient solid-state lighting. Adv Opt Mater 2014; 2: 809–836.

Round HJ . A note on carborundum. Electr World 1907; 49: 308.

Losev OV . Luminous carborundum detector and detection with crystals. Telegr Telef Prov 1927; 44: 485–494.

Wolff GA, Hebert RA, Broder JD . Electroluminescence of GaP. Phys Rev 1955; 100: 1144–1145.

Braunstein R . Radiative transitions in semiconductors. Phys Rev 1955; 99: 1892–1893.

Holonyak Jr N, Bevacqua SF . Coherent (visible) light emission from Ga(As1−xPx junctions. Appl Phys Lett 1962; 1: 82–83.

Pankove JI . Tunneling-assisted photon emission in gallium arsenide pn junctions. Phys Rev Lett 1962; 9: 283–285.

Itoh K, Kawamoto T, Amano H, Hiramatsu K, Akasaki I . Metalorganic vapor phase epitaxial growth and properties of GaN/Al0.1Ga0.9N layered structures. Jpn J Appl Phys 1991; 30: 1924.

Nakamura S, Senoh M, Mukai T . p-GaN/N-InGaN/N-GaN double-heterostructure blue-light-emitting diodes. Jpn J Appl Phys 1993; 32: L8.

Nakamura S, Mukai T, Senoh M . Candela‐class high‐brightness InGaN/AlGaN double‐heterostructure blue‐light‐emitting diodes. Appl Phys Lett 1994; 64: 1687–1689.

Krames MR, Shchekin OB, Mueller-Mach R, Mueller GO, Zhou L et al. Status and future of high-power light-emitting diodes for solid-state lighting. J Disp Technol 2007; 3: 160–175.

Koenderink AF, Alù A, Polman A . Nanophotonics: shrinking light-based technology. Science 2015; 348: 516–521.

Barnes WL, Dereux A, Ebbesen TW . Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 2003; 424: 824–830.

Biteen JS, Pacifici D, Lewis NS, Atwater HA . Enhanced radiative emission rate and quantum efficiency in coupled silicon nanocrystal-nanostructured gold emitters. Nano Lett 2005; 5: 1768–1773.

Anger P, Bharadwaj P, Novotny L . Enhancement and quenching of single-molecule fluorescence. Phys Rev Lett 2006; 96: 113002.

Kühn S, Håkanson U, Rogobete L, Sandoghdar V . Enhancement of single-molecule fluorescence using a gold nanoparticle as an optical nanoantenna. Phys Rev Lett 2006; 97: 017402.

Pillai S, Catchpole KR, Trupke T, Zhang G, Zhao J et al. Enhanced emission from Si-based light-emitting diodes using surface plasmons. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 88: 161102.

Muskens OL, Giannini V, Sánchez-Gil JA, Rivas JG . Strong enhancement of the radiative decay rate of emitters by single plasmonic nanoantennas. Nano Lett 2007; 7: 2871–2875.

Biteen JS, Sweatlock LA, Mertens H, Lewis NS, Polman A et al. Plasmon-enhanced photoluminescence of silicon quantum dots: simulation and experiment. J Phys Chem C 2007; 111: 13372–13377.

Iwase H, Englund D, Vučković J . Spontaneous emission control in high-extraction efficiency plasmonic crystals. Opt Express 2008; 16: 426–434.

Ringler M, Schwemer A, Wunderlich M, Nichtl A, Kürzinger K et al. Shaping emission spectra of fluorescent molecules with single plasmonic nanoresonators. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 100: 203002.

Kinkhabwala A, Yu Z F, Fan S H, Avlasevich Y, Müllen K et al. Large single-molecule fluorescence enhancements produced by a bowtie nanoantenna. Nat Photon 2009; 3: 654–657.

Vecchi G, Giannini V, Rivas JG . Shaping the fluorescent emission by lattice resonances in plasmonic crystals of nanoantennas. Phys Rev Lett 2009; 102: 146807.

Bharadwaj P, Deutsch B, Novotny L . Optical antennas. Adv Opt Photonics 2009; 1: 438–483.

Walters RJ, van Loon RVA, Brunets I, Schmitz J, Polman A . A silicon-based electrical source of surface plasmon polaritons. Nat Mater 2010; 9: 21–25.

Schuller JA, Barnard ES, Cai W S, Jun YC, White JS et al. Plasmonics for extreme light concentration and manipulation. Nat Mater 2010; 9: 193–204.

Curto AG, Volpe G, Taminiau TH, Kreuzer MP, Quidant R et al. Unidirectional emission of a quantum dot coupled to a nanoantenna. Science 2010; 329: 930–933.

Aouani H, Mahboub O, Bonod N, Devaux E, Popov E et al. Bright unidirectional fluorescence emission of molecules in a nanoaperture with plasmonic corrugations. Nano Lett 2011; 11: 637–644.

Aouani H, Mahboub O, Devaux E, Rigneault H, Ebbesen TW et al. Plasmonic antennas for directional sorting of fluorescence emission. Nano Lett 2011; 11: 2400–2406.

Rodriguez SRK, Lozano G, Verschuuren MA, Gomes R, Lambert K et al. Quantum rod emission coupled to plasmonic lattice resonances: a collective directional source of polarized light. Appl Phys Lett 2012; 100: 111103.

Zhou W, Dridi M, Suh JY, Kim CH, Co DT et al. Lasing action in strongly coupled plasmonic nanocavity arrays. Nat Nanotechnol 2013; 8: 506–511.

Lozano G, Louwers DJ, Rodriguez SRK, Murai S, Jansen OTA et al. Plasmonics for solid-state lighting: enhanced excitation and directional emission of highly efficient light sources. Light Sci Appl 2013; 2: e66.

Langguth L, Punj D, Wenger J, Koenderink AF . Plasmonic band structure controls single-molecule fluorescence. ACS Nano 2013; 7: 8840–8848.

Greffet JJ . Nanoantennas for light emission. Science 2005; 308: 1561–1563.

Mühlschlegel P, Eisler HJ, Martin OJF, Hecht B, Pohl DW . Resonant optical antennas. Science 2005; 308: 1607–1609.

Gontijo I, Boroditsky M, Yablonovitch E, Keller S, Mishra UK et al. Coupling of InGaN quantum-well photoluminescence to silver surface plasmons. Phys Rev B 1999; 60: 11564.

Eggleston MS, Messer K, Zhan L, Yablonovitch E, Wu MC . Optical antenna enhanced spontaneous emission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: 1704–1709.

Hecker NE, Höpfel RA, Sawaki N . Enhanced light emission from a single quantum well located near a metal coated surface. Physica E 1998; 2: 98–101.

Vuckovic J, Loncar M, Scherer A . Surface plasmon enhanced light-emitting diode. IEEE J Quantum Electron 2000; 36: 1131–1144.

Neogi A, Lee CW, Everitt HO, Kuroda T, Tackeuchi A et al. Enhancement of spontaneous recombination rate in a quantum well by resonant surface plasmon coupling. Phys Rev B 2002; 66: 153305.

Lozano G, Grzela G, Verschuuren MA, Ramezani M, Rivas JG . Tailor-made directional emission in nanoimprinted plasmonic-based light-emitting devices. Nanoscale 2014; 2014: 9223–9229.

Kido J, Kimura M, Nagai K . Multilayer white light-emitting organic electroluminescent device. Science 1995; 267: 1332–1334.

Sheats JR, Antoniadis H, Hueschen M, Leonard W, Miller J et al. Organic electroluminescent devices. Science 1996; 273: 884–888.

D'Andrade BW, Forrest SR . White organic light‐emitting devices for solid‐state lighting. Adv Mater 2004; 16: 1585–1595.

So F, Kindo J, Burrows P . Organic light-emitting devices for solid-state lighting. MRS Bull 2008; 33: 663–669.

Reineke S, Lindner F, Schwartz G, Seidler N, Walzer K et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 2009; 459: 234–238.

Tyan YS . Organic light-emitting-diode lighting overview. J Photon Energy 2011; 1: 011009.

Gather MC, Köhnen A, Meerholz K . White organic light‐emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2011; 23: 233–248.

Reineke S, Thomschke M, Lüssem B, Leo K . White organic light-emitting diodes: status and perspective. Rev Mod Phys 2013; 85: 1245–1293.

Pei QB, Yu G, Zhang C, Yang Y, Heeger AJ . Polymer light-emitting electrochemical cells. Science 1995; 269: 1086–1088.

Meier SB, Tordera D, Pertegás A, Roldán-Carmona C, Ortí E et al. Light-emitting electrochemical cells: recent progress and future prospects. Mater Today 2014; 17: 217–223.

Pimputkar S, Speck JS, DenBaars SP, Nakamura S . Prospects for LED lighting. Nat Phtoton 2009; 3: 180–182.

Žukauskas A, Shur MS, Gaska R . Introduction to Solid-State Lighting. New York: Wiley. 2002.

Steigerwald DA, Bhat JC, Collins D, Fletcher RM, Holcomb MO et al. Illumination with solid state lighting technology. IEEE J Sel Topics Quantum Electron 2002; 8: 310–320.

Shur MS, Žukauskas A . Solid-state lighting: toward superior illumination. Proc IEEE 2005; 93: 1691–1703.

Hong YJ, Lee CH, Yoon A, Kim M, Seong HK et al. Visible-color-tunable light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2011; 23: 3284–3288.

Qian F, Gradečak S, Li Y, Wen CY, Lieber CM . Core/multishell nanowire heterostructures as multicolor, high-efficiency light-emitting diodes. Nano Lett 2005; 5: 2287–2291.

Funato M, Hayashi K, Ueda M, Kawakami Y, Narukawa Y et al. Emission color tunable light-emitting diodes composed of InGaN multifacet quantum wells. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 93: 021126.

Limbach F, Hauswald C, Lähnemann J, Wölz M, Brandt O et al. Current path in light emitting diodes based on nanowire ensembles. Nanotechnology 2012; 23: 465301.

Li SF, Waag A . GaN based nanorods for solid state lighting. J Appl Phys 2012; 111: 071101.

Bengoechea-Encabo A, Albert S, Lopez-Romero D, Lefebvre P, Barbagini F et al. Light-emitting-diodes based on ordered InGaN nanocolumns emitting in the blue, green and yellow spectral range. Nanotechnology 2014; 25: 435203.

Höppe HA . Recent developments in the field of inorganic phosphors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009; 48: 3572–3582.

Smet PF, Parmentier AB, Poelman D . Selecting conversion phosphors for white light-emitting diodes. J Electrochem Soc 2011; 158: R37–R54.

Lin CC, Liu RS . Advances in phosphors for light-emitting diodes. J Phys Chem Lett 2011; 2: 1268–1277.

Demir HV, Nizamoglu S, Erdem T, Mutlugun E, Gaponik N et al. Quantum dot integrated LEDs using photonic and excitonic color conversion. Nano Today 2011; 6: 632–647.

Dohnalová K, Poddubny AN, Prokofiev AA, de Boer WDAM, Umesh CP et al. Surface brightens up Si quantum dots: direct bandgap-like size-tunable emission. Light Sci Appl 2013; 2: e47.

Li XF, Budai JD, Liu F, Howe JY, Zhang JH et al. New yellow Ba0.93Eu0.07Al2O4 phosphor for warm-white light-emitting diodes through single-emitting-center conversion. Light Sci Appl 2013; 2: e50.

Zhang R, Lin H, Yu YL, Chen DQ, Xu J et al. A new-generation color converter for high-power white LED: transparent Ce3+: YAG phosphor-in-glass. Laser Photon Rev 2014; 8: 158–164.

Pust P, Weiler V, Hecht C, Tücks A, Wochnik AS et al. Narrow-band red-emitting Sr[LiAl3N4]: Eu2+ as a next-generation LED-phosphor material. Nat Mater 2014; 13: 891–896.

Pust P, Schmidt PJ, Schnick W . A revolution in lighting. Nat Mater 2015; 14: 454–458.

Zhu HM, Lin CC, Luo WQ, Shu ST, Liu ZG et al. Highly efficient non-rare-earth red emitting phosphor for warm white light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4312.

Meyer J, Tappe F . Photoluminescent materials for solid-state lighting: state of the art and future challenges. Adv Opt Mater 2015; 3: 424–430.

Liu ZY, Liu S, Wang K, Luo XB . Measurement and numerical studies of optical properties of YAG: Ce phosphor for white light-emitting diode packaging. Appl Opt 2010; 49: 247–257.

Vos WL, Tukker TW, Mosk AP, Lagendijk A, IJzerman WL . Broadband mean free path of diffuse light in polydisperse ensembles of scatterers for white light-emitting diode lighting. Appl Opt 2013; 52: 2602–2609.

Leung VYF, Lagendijk A, Tukker TW, Mosk AP, IJzerman WL et al. Interplay between multiple scattering, emission, and absorption of light in the phosphor of a white light-emitting diode. Opt Express 2014; 22: 8190–8204.

Oh JH, Yang SJ, Do YR . Healthy, natural, efficient and tunable lighting: four-package white LEDs for optimizing the circadian effect, color quality and vision performance. Light Sci Appl 2014; 3: e141.

Frimmer M, Chen Y, Koenderink AF . Scanning emitter lifetime imaging microscopy for spontaneous emission control. Phys Rev Lett 2011; 107: 123602.

Guo K, Lozano G, Verschuuren MA, Gómez-Rivas J . Control of the external photoluminescent quantum yield of emitters coupled to nanoantenna phased arrays. J Appl Phys 2015; 118: 073103.

Barnes WL . Electromagnetic crystals for surface plasmon polaritons and the extraction of light from emissive devices. J Lightwave Technol 1999; 17: 2170–2182.

Khurgin JB, Sun G, Soref RA . Enhancement of luminescence efficiency using surface plasmon polaritons: figures of merit. J Opt Soc Am B 2007; 24: 1968–1980.

Sun G, Khurgin JB, Soref RA . Plasmonic light-emission enhancement with isolated metal nanoparticles and their coupled arrays. J Opt Soc Am B 2008; 25: 1748–1755.

Paiella R . Tunable surface plasmons in coupled metallo-dielectric multiple layers for light-emission efficiency enhancement. Appl Phys Lett 2005; 87: 111104.

Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC . The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J Phys Chem B 2003; 107: 668–677.

Song JH, Atay T, Shi SF, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV . Large enhancement of fluorescence efficiency from CdSe/ZnS quantum dots induced by resonant coupling to spatially controlled surface plasmons. Nano Lett 2005; 5: 1557–1561.

Tam F, Goodrich GP, Johnson BR, Halas NJ . Plasmonic enhancement of molecular fluorescence. Nano Lett 2007; 7: 496–501.

Giannini V, Sánchez-Gil JA, Muskens OL, Rivas JG . Electrodynamic calculations of spontaneous emission coupled to metal nanostructures of arbitrary shape: nanoantenna-enhanced fluorescence. J Opt Soc Am B 2009; 26: 1569–1577.

Mertens H, Polman A . Strong luminescence quantum-efficiency enhancement near prolate metal nanoparticles: dipolar versus higher-order modes. J Appl Phys 2009; 105: 044302.

Bharadwaj P, Novotny L . Plasmon-enhanced photoemission from a single Y3N@C80 fullerene. J Phys Chem C 2010; 114: 7444–7447.

Wenger J . Fluorescence enhancement factors on optical antennas: enlarging the experimental values without changing the antenna design. Int J Opt 2012; 2012: 828121.

Carron KT, Fluhr W, Meier M, Wokaun A, Lehmann HW . Resonances of two-dimensional particle gratings in surface-enhanced Raman scattering. J Opt Soc Am B 1986; 3: 430–440.

Markel VA . Antisymmetrical optical states. J Opt Soc Am B 1995; 12: 1783–1791.

Zou SL, Schatz GC . Narrow plasmonic/photonic extinction and scattering line shapes for one and two dimensional silver nanoparticle arrays. J Chem Phys 2004; 121: 12606–12612.

Hicks EM, Zou SL, Schatz GC, Spears KG, Van Duyne RP et al. Controlling plasmon line shapes through diffractive coupling in linear arrays of cylindrical nanoparticles fabricated by electron beam lithography. Nano Lett 2005; 5: 1065–1070.

Chu YZ, Schonbrun E, Yang T, Crozier KB . Experimental observation of narrow surface plasmon resonances in gold nanoparticle arrays. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 93: 181108.

Auguié B, Barnes WL . Collective resonances in gold nanoparticle arrays. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 101: 143902.

Kravets VG, Schedin F, Grigorenko AN . Extremely narrow plasmon resonances based on diffraction coupling of localized plasmons in arrays of metallic nanoparticles. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 101: 087403.

Vecchi G, Giannini V, Rivas JG . Surface modes in plasmonic crystals induced by diffractive coupling of nanoantennas. Phys Rev B 2009; 80: 201401.

Rodriguez SRK, Abass A, Maes B, Janssen OTA, Vecchi G et al. Coupling bright and dark plasmonic lattice resonances. Phys Rev X 2011; 1: 021019.

Zhou W, Odom TW . Tunable subradiant lattice plasmons by out-of-plane dipolar interactions. Nat Nanotechnol 2011; 6: 423–427.

Rodriguez SRK, Schaafsma MC, Berrier A, Gómez-Rivas J . Collective resonances in plasmonic crystals: size matters. Physica B 2012; 407: 4081–4085.

Teperik TV, Degiron A . Design strategies to tailor the narrow plasmon-photonic resonances in arrays of metallic nanoparticles. Phys Rev B 2012; 86: 245425.

Abass A, Rodriguez SRK, Rivas JG, Maes B . Tailoring dispersion and Eigenfield profiles of plasmonic surface lattice resonances. ACS Photon 2014; 1: 61–68.

de Abajo FJG . Colloquium: light scattering by particle and hole arrays. Rev Mod Phys 2007; 79: 1267–1290.

Christ A, Tikhodeev SG, Gippius NA, Kuhl J, Giessen H . Waveguide-plasmon polaritons: strong coupling of photonic and electronic resonances in a metallic photonic crystal slab. Phys Rev Lett 2003; 91: 183901.

Zentgraf T, Zhang S, Oulton RF, Zhang X . Ultranarrow coupling-induced transparency bands in hybrid plasmonic systems. Phys Rev B 2009; 80: 195415.

Rodriguez SRK, Murai S, Verschuuren MA, Rivas JG . Light-emitting waveguide-plasmon polaritons. Phys Rev Lett 2012; 109: 166803.

Murai S, Verschuuren MA, Lozano G, Pirruccio G, Rodriguez SRK et al. Hybrid plasmonic-photonic modes in diffractive arrays of nanoparticles coupled to light-emitting optical waveguides. Opt Express 2013; 21: 4250–4262.

Pellegrini G, Mattei G, Mazzoldi P . Nanoantenna arrays for large-area emission enhancement. J Phys Chem C 2011; 115: 24662–24665.

Shi L, Hakala TK, Rekola HT, Martikainen JP, Moerland RJ et al. Spatial coherence properties of organic molecules coupled to plasmonic surface lattice resonances in the weak and strong coupling regimes. Phys Rev Lett 2014; 112: 153002.

Shi L, Yuan XW, Zhang YF, Hakala TK, Yin SY et al. Coherent fluorescence emission by using hybrid photonic-plasmonic crystals. Laser Photon Rev 2014; 8: 717–725.

Lozano G, Barten T, Grzela G, Rivas JG . Directional absorption by phased arrays of plasmonic nanoantennae probed with time-reversed Fourier microscopy. New J Phys 2014; 16: 013040.

Wiesmann C, Bergenek K, Linder N, Schwarz UT . Photonic crystal LEDs-designing light extraction. Laser Photon Rev 2009; 3: 262–286.

Matioli E, Weisbuch C . Impact of photonic crystals on LED light extraction efficiency: approaches and limits to vertical structure designs. J Phys D Appl Phys 2010; 43: 354005.

David A, Benisty H, Weisbuch C . Photonic crystal light-emitting sources. Rep Prog Phys 2012; 75: 126501.

Kim DH, Cho CO, Roh YG, Jeon H, Park YS et al. Enhanced light extraction from GaN-based light-emitting diodes with holographically generated two-dimensional photonic crystal patterns. Appl Phys Lett 2005; 87: 203508.

Gong HB, Hao XP, Wu YZ, Cao BQ, Xia W et al. Enhanced light extraction from GaN-based LEDs with a bottom-up assembled photonic crystal. Mater Sci Eng B 2011; 176: 1028–1031.

Lawrence N, Trevino J, Dal Negro L . Aperiodic arrays of active nanopillars for radiation engineering. J Appl Phys 2012; 111: 113101.

Wierer Jr JJ, David A, Megens MM . III-nitride photonic-crystal light-emitting diodes with high extraction efficiency. Nat Photon 2009; 3: 163–169.

Matioli E, Brinkley S, Kelchner KM, Hu YL, Nakamura S et al. High-brightness polarized light-emitting diodes. Light Sci Appl 2012; 1: e22.

Ding P, Li MY, He JN, Wang JQ, Fan CZ et al. Guided mode caused by silicon nanopillar array for light emission enhancement in color-converting LED. Opt Express 2015; 23: 21477–21489.

Okamoto K, Niki I, Shvartser A, Narukawa Y, Mukai T et al. Surface-plasmon-enhanced light emitters based on InGaN quantum wells. Nat Mater 2004; 3: 601–605.

Gu XF, Qiu T, Zhang WJ, Chu PK . Light-emitting diodes enhanced by localized surface plasmon resonance. Nanoscale Res Lett 2011; 6: 199.

Chu WH, Chuang YJ, Liu CP, Lee PI, Hsu SLC . Enhanced spontaneous light emission by multiple surface plasmon coupling. Opt Express 2010; 18: 9677–9683.

Barnes WL . Fluorescence near interfaces: the role of photonic mode density. J Mod Opt 1998; 45: 661–669.

DiMaria J, Dimakis E, Moustakas TD, Paiella R . Plasmonic off-axis unidirectional beaming of quantum-well luminescence. Appl Phys Lett 2013; 103: 251108.

Fujii T, Gao Y, Sharma R, Hu EL, DenBaars SP, Nakamura S . Increase in the extraction efficiency of GaN-based light-emitting diodes via surface roughening. Appl Phys Lett 2004; 84: 855–857.

Hecker NE, Höpfel RA, Sawaki N, Maier T, Strasser G . Surface plasmon-enhanced photoluminescence from a single quantum well. Appl Phys Lett 1999; 75: 1577–1579.

Henson J, DiMaria J, Dimakis E, Moustakas TD, Paiella R . Plasmon-enhanced light emission based on lattice resonances of silver nanocylinder arrays. Opt Lett 2012; 37: 79–81.

Sadi T, Oksanen J, Tulkki J . Effect of plasmonic losses on light emission enhancement in quantum-wells coupled to metallic gratings. J Appl Phys 2013; 114: 223104.

David A, Fujii T, Matioli E, Sharma R, Nakamura S et al. GaN light-emitting diodes with Archimedean lattice photonic crystals. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 88: 073510.

Giannini V, Vecchi G, Rivas JG . Lighting up multipolar surface plasmon polaritons by collective resonances in arrays of nanoantennas. Phys Rev Lett 2010; 105: 266801.

Teperik T, Degiron A . Control of plasmonic crystal light emission. J Opt Soc Am B 2014; 31: 223–228.

Rodriguez SRK, Arango FB, Steinbusch TP, Verschuuren MA, Koenderink AF et al. Breaking the symmetry of forward-backward light emission with localized and collective magnetoelectric resonances in arrays of pyramid-shaped aluminum nanoparticles. Phys Rev Lett 2014; 113: 247401.

Jin P, Tazawa M, Xu G . Reversible tuning of surface plasmon resonance of silver nanoparticles using a thermochromic matrix. J Appl Phys 2006; 99: 096106.

Olcum S, Kocabas A, Ertas G, Atalar A, Aydinli A . Tunable surface plasmon resonance on an elastomeric substrate. Opt Express 2009; 17: 8542–8547.

Beeckman J, Neyts K, Vanbrabant PJM . Liquid-crystal photonic applications. Opt Eng 2011; 50: 081202.

Lumdee C, Toroghi S, Kik PG . Post-fabrication voltage controlled resonance tuning of nanoscale plasmonic antennas. ACS Nano 2012; 6: 6301–6307.

Müller J, Sönnichsen C, von Poschinger H, von Plessen G, Klar TA et al. Electrically controlled light scattering with single metal nanoparticles. Appl Phys Lett 2002; 81: 171–173.

Kossyrev PA, Yin AJ, Cloutier SG, Cardimona DA, Huang DH et al. Electric field tuning of plasmonic response of nanodot array in liquid crystal matrix. Nano Lett 2005; 5: 1978–1981.

Chu KC, Chao CY, Chen YF, Wu YC, Chen CC . Electrically controlled surface plasmon resonance frequency of gold nanorods. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 89: 103107.

Evans PR, Wurtz GA, Hendren WR, Atkinson R, Dickson W et al. Electrically switchable nonreciprocal transmission of plasmonic nanorods with liquid crystal. Appl Phys Lett 2007; 91: 043101.

Dickson W, Wurtz GA, Evans PR, Pollard RJ, Zayats AV . Electronically controlled surface plasmon dispersion and optical transmission through metallic hole arrays using liquid crystal. Nano Lett 2008; 8: 281–286.

Khatua S, Chang WS, Swanglap P, Olson J, Link S . Active modulation of nanorod plasmons. Nano Lett 2011; 11: 3797–3802.

Li HB, Xu SP, Gu YJ, Wang K, Xu WQ . Active modulation of wavelength and radiation direction of fluorescence via liquid crystal-tuned surface plasmons. Appl Phys Lett 2013; 102: 051107.

Abbas A, Rodriguez SRK, Ako T, Aubert T, Verschuuren MA et al. Active liquid crystal tuning of metallic nanoantenna enhanced light emission from colloidal quantum dots. Nano Lett 2014; 14: 5555–5560.

Bellessa J, Bonnand C, Plenet JC, Mugnier J . Strong coupling between surface plasmons and excitons in an organic semiconductor. Phys Rev Lett 2004; 93: 036404.

Hakala TK, Toppari JJ, Kuzyk A, Pettersson M, Tikkanen H et al. Vacuum rabi splitting and strong-coupling dynamics for surface-plasmon polaritons and rhodamine 6G molecules. Phys Rev Lett 2009; 103: 053602.

González-Tudela A, Huidobro PA, Martín-Moreno L, Tejedor C, García-Vidal FJ . Theory of strong coupling between quantum emitters and propagating surface plasmons. Phys Rev Lett 2013; 110: 126801.

Dintinger J, Klein S, Bustos F, Barnes WL, Ebbesen TW . Strong coupling between surface plasmon-polaritons and organic molecules in subwavelength hole arrays. Phys Rev B 2005; 71: 035424.

Vasa P, Pomraenke R, Schwieger S, Mazur YI, Kunets V et al. Coherent exciton–surface-plasmon-polariton interaction in hybrid metal-semiconductor nanostructures. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 101: 116801.

Schwartz T, Hutchison JA, Genet C, Ebbesen TW . Reversible switching of ultrastrong light-molecule coupling. Phys Rev Lett 2011; 106: 196405.

Sugawara Y, Kelf TA, Baumberg JJ, Abdelsalam ME, Bartlett PN . Strong coupling between localized plasmons and organic excitons in metal nanovoids. Phys Rev Lett 2006; 97: 266808.

Cade NI, Ritman-Meer T, Richards D . Strong coupling of localized plasmons and molecular excitons in nanostructured silver films. Phys Rev B 2009; 79: 241404.

Manjavacas A, de Abajo FJG, Nordlander P . Quantum plexcitonics: strongly interacting plasmons and excitons. Nano Lett 2011; 11: 2318–2323.

Zengin G, Wersäll M, Nilsson S, Antosiewicz TJ, Käll M et al. Realizing strong light-matter interactions between single-nanoparticle plasmons and molecular excitons at ambient conditions. Phys Rev Lett 2015; 114: 157401.

Rodriguez SRK, Feist J, Verschuuren MA, Vidal FJG, Rivas JG . Thermalization and cooling of plasmon-exciton polaritons: towards quantum condensation. Phys Rev Lett 2013; 111: 166802.

Väkeväinen AI, Moerland RJ, Rekola HT, Eskelinen AP, Martikainen JP et al. Plasmonic surface lattice resonances at the strong coupling regime. Nano Lett 2014; 14: 1721–1727.

Rodriguez SRK, Rivas JG . Surface lattice resonances strongly coupled to Rhodamine 6G excitons: tuning the plasmon-exciton-polariton mass and composition. Opt Express 2013; 21: 27411–27421.

Törmä P, Barnes WL . Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and emitters: a review. Rep Prog Phys 2015; 78: 013901.

Penzkofer A, Leupacher W . Fluorescence behaviour of highly concentrated rhodamine 6G solutions. J Luminesc 1987; 37: 61–72.

Shen YC, Mueller GO, Watanabe S, Gardner NF, Munkholm A et al. Auger recombination in InGaN measured by photoluminescence. Appl Phys Lett 2007; 91: 141101.

Verzellesi G, Saguatti D, Meneghini M, Bertazzi F, Goano M et al. Efficiency droop in InGaN/GaN blue light-emitting diodes: physical mechanisms and remedies. J Appl Phys 2013; 14: 071101.

Iveland J, Martinelli L, Peretti J, Speck JS, Weisbuch C . Direct measurement of auger electrons emitted from a semiconductor light-emitting diode under electrical injection: identification of the dominant mechanism for efficiency droop. Phys Rev Lett 2013; 110: 177406.

Wierer JJ, Tsao JY, Sizov DS . Comparison between blue lasers and light-emitting diodes for future solid-state lighting. Laser Photon Rev 2013; 7: 963–993.

Meier M, Mekis A, Dodabalapur A, Timko A, Slusher RE et al. Laser action from two-dimensional distributed feedback in photonic crystals. Appl Phys Lett 2009; 74: 7–9.

Painter O, Lee RK, Scherer A, Yariv A, O’Brien JD et al. Two-dimensional photonic band-gap defect mode laser. Science 1999; 284: 1819–1821.

Altug H, Englund D, Vučković J . Ultrafast photonic crystal nanocavity laser. Nat Phys 2006; 2: 484–488.

Hirose K, Liang Y, Kurosaka Y, Watanabe A, Sugiyama T et al. Watt-class high-power, high-beam-quality photonic-crystal lasers. Nat Photon 2014; 8: 406–411.

Oulton RF, Sorger VJ, Zentgraf T, Ma RM, Gladden C et al. Plasmon lasers at deep subwavelength scale. Nature 2009; 461: 629–632.

Stehr J, Crewett J, Schindler F, Sperling R, von Plessen G et al. A low threshold polymer laser based on metallic nanoparticle gratings. Adv Mater 2003; 15: 1726–1729.

van Beijnum F, van Veldhoven PJ, Geluk EJ, de Dood MJA, Hooft GW et al. Surface plasmon lasing observed in metal hole arrays. Phys Rev Lett 2013; 110: 206802.

Suh JY, Kim CH, Zhou W, Huntington MD, Co DT et al. Plasmonic bowtie nanolaser arrays. Nano Lett 2012; 12: 5769–5774.

Schokker AH, Koenderink AF . Lasing at the band edges of plasmonic lattices. Phys Rev B 2014; 90: 155452.

Yang AK, Hoang TB, Dridi M, Deeb C, Mikkelsen MH et al. Real-time tunable lasing from plasmonic nanocavity arrays. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6939.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO) through the project LEDMAP of the Technology Foundation STW and through the Industrial Partnership Program Nanophotonics for Solid State Lighting between Philips and the Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter FOM. It is also supported by NanoNextNL of the Government of the Netherlands and 130 partners.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lozano, G., Rodriguez, S., Verschuuren, M. et al. Metallic nanostructures for efficient LED lighting. Light Sci Appl 5, e16080 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.80

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.80

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Efficiency enhancement of micro-light-emitting diode with shrinking size by localized surface plasmons coupling

Applied Physics B (2024)

-

A multi-mode super-fano mechanism for enhanced third harmonic generation in silicon metasurfaces

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

Room-temperature electrical control of polarization and emission angle in a cavity-integrated 2D pulsed LED

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Efficiency improvement of AlGaN-based deep ultraviolet LEDs with gradual Al-composition AlGaN conduction layer

Optoelectronics Letters (2020)

-

Spontaneous emission rate enhancement with aperiodic Thue-Morse multilayer

Scientific Reports (2019)