Abstract

It is not known whether patient age or tumor characteristics such as tumor regression or solar elastosis influence pathologists’ interpretation of melanocytic skin lesions (MSLs). We undertook a study to determine the influence of these factors, and to explore pathologist's characteristics associated with the direction of diagnosis. To meet our objective, we designed a cross-sectional survey study of pathologists’ clinical practices and perceptions. Pathologists were recruited from diverse practices in 10 states in the United States. We enrolled 207 pathologist participants whose practice included the interpretation of MSLs. Our findings indicated that the majority of pathologists (54.6%) were influenced toward a less severe diagnosis when patients were <30 years of age. Most pathologists were influenced toward a more severe diagnosis when patients were >70 years of age, or by the presence of tumor regression or solar elastosis (58.5%, 71.0%, and 57.0%, respectively). Generally, pathologists with dermatopathology board certification and/or a high caseload of MSLs were more likely to be influenced, whereas those with more years’ experience interpreting MSL were less likely to be influenced. Our findings indicate that the interpretation of MSLs is influenced by patient age, tumor regression, and solar elastosis; such influence is associated with dermatopathology training and higher caseload, consistent with expertise and an appreciation of lesion complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Melanoma staging is determined by histologic characteristics that are known to influence patient outcomes including tumor depth, ulceration, and mitotic rate.1, 2, 3 Of these, tumor depth was the first prognostic factor to be identified4 and remains the strongest predictor of patient outcomes in the absence of tumor extension or metastases.1

Although these characteristics form the basis of pathologists’ interpretations of melanocytic skin lesions (MSL), it remains unclear whether additional characteristics of the lesions or patients also influence interpretations. For example, younger patients, compared with older patients, have lower melanoma incidence rates5 and higher melanoma survival rates.6 Consequently, younger patient age might influence pathologists toward a less severe diagnosis, whereas older patient age may influence toward a more severe diagnosis.

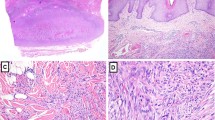

The potential influence of partial tumor regression, uncommon in benign nevi but reported in up to 58% of melanomas,7 is more difficult to anticipate. To the extent that tumor regression obscures depth of invasion, its presence might influence pathologists toward a more severe diagnosis. On the other hand, melanoma tumor regression may be thought to represent local host immune response,8 a potentially favorable process. Studies of associations between partial tumor regression and metastasis or survival have produced mixed results, with some showing improved outcome9, 10 and others showing worse outcome.11, 12, 13

Similarly, it is difficult to predict the potential influence of solar elastosis on the direction of pathologists’ diagnosis. More common in older patients,14 solar elastosis is a microscopic marker of chronic sun exposure,15 and a diagnostic criterion of certain melanoma subtypes.16 Thus, its presence might increase suspicion of an atypical melanocytic lesion or melanoma, swaying pathologists toward a more severe diagnosis. On the other hand, several studies suggest improved melanoma outcome for patients affected by solar elastosis,3, 17, 18 which might influence pathologists toward a less severe diagnosis. Whether pathologists consider these factors in their diagnostic interpretations is not known. To address this gap in knowledge, we sought to determine whether certain contexts (ie, patient age, tumor regression, and solar elastosis) influence the severity of pathologists’ diagnoses when interpreting MSLs. We also assessed pathologist characteristics in relation to the direction of influence within each context found to be influential.

Although this report does not represent a traditional experimental study, it addresses the important issue of contexts that influence pathology diagnoses.

Materials and methods

Study Design and Sample Selection

We conducted a study of pathologists who interpret MSL, including benign nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanoma. Approval from the Institutional Review Board for all study procedures was obtained from the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Rhode Island Hospital, and Dartmouth College. Pathologists were recruited from community practices/laboratories and academic medical centers in 10 states (CA, CT, HI, IA, KY, LA, NJ, NM, UT, and WA). We identified potential participants using Internet searches, professional organizations, and telephone calls to pathology laboratories/practices. Pathologists were invited to participate via e-mail, postal mail, and telephone from July 2013 through August 2014. Eligibility criteria included completion of residency training and/or fellowship training, interpretation of MSL within the previous year, expected continuation of interpreting MSL for the following two years while working in the same state, and verifiable address of practice location.

Survey Content

After consenting to participate, pathologists completed an online survey that elicited general demographic and professional information, including training, practice, and perceptions. A full copy of the survey is available at http://depts.washington.edu/epidem/faculty/elmore-joann.

Pathologists were asked whether each of certain contexts influenced the direction of their diagnosis of MSL. The potentially influential contexts included patient-level characteristics (patient age <30 and patient age >70) and tumor-level characteristics (areas of extensive tumor regression and significant solar elastosis).

Primary Outcome

The primary analytic outcome was the direction of diagnostic influence: influence toward a less severe diagnosis, no influence on diagnosis, and influence toward a more severe diagnosis. The vast majority of responses (≥96% within each context) included the no-influence category and only one direction of influence; consequently, the primary outcome was dichotomized as follows: (a) ‘influence toward a less severe diagnosis’ vs ‘no influence’ or (b) ‘influence toward a more severe diagnosis’ vs ‘no influence,’ depending on pathologists’ responses for each context. For example, in the context of tumor regression, 99% of pathologists reported either influence toward a more severe diagnosis or no influence on diagnosis. Thus, in this context, the primary outcome consisted of ‘influence toward a more severe diagnosis’ vs ‘no influence.’

Pathologist Characteristics

We also explored pathologist's characteristics in relation to diagnostic influence. Variables of interest included pathologist age, gender, residency training, dermatopathology (DP) fellowship training, DP board certification, MSL caseload (defined as the per month sum of benign MSL cases and melanoma/melanoma in situ cases), percentage of cases rendered as borderline or uncertain diagnoses in their final assessment, whether the pathologist requested second opinions from other pathologists (within or outside their practice) at least once per month, and whether pathologists requested specialized molecular tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or comparative genomic hybridization (CGH).

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary analyses showed that pathologists' age and years of interpreting MSL were highly correlated (r=0.85; P<0.0001), precluding simultaneous inclusion in multivariable models; thus, we chose to evaluate years of interpreting MSL due to its greater relevance. Owing to almost perfect concordance between DP fellowship training and board certification, we chose DP board certification to represent specialized knowledge in DP. DP board certification was highly correlated with higher MSL caseload (r=0.64; P<0.0001), and both were considered key variables. To incorporate both into our analysis, we created a three-level composite variable representing DP expertise: (1) no DP certification and low MSL caseload (<35 MSL/month), (2) no DP certification and high MSL caseload (≥35 MSL/month), and (3) DP certification (regardless of caseload). Two variables, the frequency of using borderline/uncertain diagnosis in final assessments and the frequency of asking for second opinions, were dichotomized as yes/no because the relationship with the outcome was not linear.

Our primary analysis described the percent of pathologists reporting a direction of diagnostic influence within each of the four contexts. Correlation matrices were used to assess relationships between pathologist characteristics. The association between pathologists’ characteristics and the direction of diagnosis was displayed in frequency distributions and assessed in logistic regression models. We began by exploring unadjusted models to identify terms for inclusion in multivariable models. Variables associated with the outcome at P<0.10 in unadjusted models were assessed in multivariable models. Variables approaching statistical significance (P<0.06) were retained in the final multivariable models to allow covariate adjustment. By convention, alpha was set at <0.05 (two-sided tests) for statistical significance in the multivariable models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Pathologist Characteristics

Of the 864 potential pathologist participants initially identified, 301 met eligibility criteria and 207 (69%) completed the online survey. The majority (54%) were aged ≥50 years (mean age 51 years) and male (59%; Table 1). A minority (39%) were board-certified in DP, with the remainder certified in anatomic pathology, clinical pathology, hematopathology, or cytopathology. The majority (69%) had interpreted MSL for less than 20 years, and for 63% the caseload was ≥35 MSL per month. Most pathologists (90%) reported ever using the terms borderline/uncertain in their final pathology report, and most (89%) reported they requested second opinions of other pathologists at least once per month.

Influence of Context on Direction of Diagnosis

The percent of pathologists reporting an influence of patient and tumor characteristics on the direction of their diagnosis within each context is shown in Figure 1. A majority of pathologists (54.6%) reported that young patients' age (<30 years) would influence them toward a less severe diagnosis, and most (58.5%) reported that older patients' age (>70 years) would influence them toward a more severe diagnosis. The majority of pathologists also reported that they would be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis in the context of extensive tumor regression (71.0%) or by the presence of significant solar elastosis (57.0%). The full distribution of pathologist characteristics associated with direction of influence within each of the four contexts is provided in the Supplementary Material As Appendix A.

Pathologist Characteristics and the Direction of Diagnosis by Context

Patient Age <30 Years

Within the context of younger patients (<30 years of age), only one variable, years of interpreting MSL, was associated with self-reported influence toward a less severe diagnosis in the unadjusted analyses; therefore, multivariable analysis was unnecessary. Compared with pathologists with less experience, those with ≥20 years of experience interpreting MSL were less likely (OR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.67; P=0.001) to be influenced toward a less severe diagnosis in the context of younger patients' age (Table 2).

Patients' Age >70 Years

Unadjusted analysis showed an association between the outcome and using the term borderline in a final diagnosis; however, this variable lost significance when adjusted for other pathologist characteristics. Two variables, DP expertise and years of interpreting MSL, remained associated with the outcome in adjusted analysis, and were included in the final multivariable model (Table 2). Compared with those without DP certification and with low MSL caseload, those with either a high MSL caseload (OR: 2.03; 95% CI: 0.96, 4.29) or DP certification (OR: 2.82; 95% CI: 1.40, 5.69) were at least twice as likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis when patients were older (global P=0.012). Compared with pathologists with less experience, those with ≥20 years experience interpreting MSL were less likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis (OR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.17, 0.63; P≤0.001).

Tumor Regression

Unadjusted analysis showed an association between the outcome and years of interpreting MSL; however, this variable lost significance after adjustment for other pathologists' characteristics. Variables that remained associated with the outcome in adjusted models were retained in the final multivariable model (Table 2) and included: DP expertise, years interpreting MSL, using the term borderline in a final diagnosis, and seeking second opinions. Compared with those without DP certification and with low MSL caseload, those with either high MSL caseload (OR: 2.87; 95% CI: 1.25, 6.60) or DP certification (OR: 2.91; 95% CI: 1.29, 6.53; global P=0.008) were more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis. Pathologists who ever used the terms borderline/uncertain when interpreting MSL were also more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis by tumor regression (OR: 4.73; 95% CI: 1.66, 13.53; P=0.004), as were those who requested second opinions at least once per month (OR: 3.04; 95% CI: 1.12, 8.26; P=0.029). Although the association was marginally significant, those with ≥20 years of experience interpreting MSL, compared with those with fewer years, were half as likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis (OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24, 1.02; P=0.057).

Solar Elastosis

Two variables, years interpreting MSL and ordering FISH/CGH or other molecular tests, were associated with the outcome in the unadjusted analysis, but were not statistically significant after adjustment for other pathologist characteristics. Three variables remained associated after adjustment, and were included in the final multivariable model: DP expertise, using borderline/uncertain diagnosis, and requesting second opinions (Table 2). Compared with non-DP-certified, low MSL volume pathologists, those with either high MSL volume (OR: 2.06; 95% CI: 0.98, 4.35) or DP certification (OR: 4.07; 95% CI: 1.98, 8.38) were more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis (global P≤0.001). Pathologists who ever used the terms borderline/uncertain when interpreting MSL were also more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis (OR: 2.94; 95% CI: 1.03, 8.37; P=0.044), as were those who requested second opinions at least once per month (OR: 5.45; 95% CI: 1.92, 15.43; P=0.001).

Discussion

We identified four influential contexts that have an impact on the severity of diagnosis: younger patient age, older patient age, tumor regression, and solar elastosis. Only one context, younger patient age, influenced pathologists toward a less severe diagnosis. The three remaining contexts influenced pathologists toward a more severe diagnosis.

Our results concerning patient age are compatible with studies showing a more favorable prognosis in younger patients than in older patients.6 In addition, melanoma is less common in younger than in older individuals;5 thus, the prior probability of disease and the predictive value of a diagnosis of melanoma are greater in older populations.

A majority of pathologists in our study reported that they were influenced toward a more severe diagnosis by melanoma with extensive tumor regression. Such influence may reflect longstanding concerns that tumors with regression have invaded beyond their measurable depth.19 Consistent with this concern, some studies have shown a worse outcome for patients with regressed tumors (reviewed in Piepkorn and Barnhill).20 Other studies, however, have indicated that tumor regression predicts better outcome, although others have shown no association (reviewed in Piepkorn and Barnhill).20 A recent meta-analysis of 14 studies,10 published after our study was underway, noted a strong, inverse association between tumor regression and lymph node metastasis, implying more favorable survival, but heterogeneity was substantial among the analyzed studies.10 It should also be noted that nearly half of melanomas disseminate without first invading the regional lymph nodes.21, 22 Thus, the prognostic role of tumor regression, which has implications for diagnostic interpretation, and possibly for staging, remains unclear.

The majority of pathologists in our study were also swayed toward a more severe diagnosis by the presence of significant solar elastosis, a biological marker of chronic sun exposure.15 This finding seems inconsistent with the relatively slow radial growth rate of lentigo maligna melanoma, the histologic subtype for which solar elastosis is a diagnostic criterion,16 and with past studies showing a favorable influence of solar elastosis on prognosis.3, 17, 18 However, solar elastosis is an indicator of long-term sun exposure, which is a known risk factor for lentigo maligna melanoma,23 and is infrequently found with benign nevi; therefore, its presence in a MSL may increase suspicion of malignancy.

We also explored pathologists' characteristics associated with influence on the direction of diagnosis. Pathologists with more years of MSL interpretation, who also were necessarily older, were less likely to be influenced toward a less severe diagnosis in the context of younger patient age. They were also less likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis in the context of older patient age and tumor regression. Although speculative, these findings may reflect complacency or overconfidence in those with long-term experience interpreting MSL.

Our findings were similar for pathologists who had high MSL caseloads, but lacked DP certification, and for those with DP board certification. Both groups were more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis in the contexts of older age, tumor regression, and solar elastosis. Those who designated tumors as borderline/uncertain in their final reports, and who requested a second opinion at least monthly, were also more likely to be influenced toward a more severe diagnosis in contexts of tumor regression or solar elastosis. These pathologist characteristics are consistent with a higher level of sophistication and appreciation of lesion complexity, although requesting second opinions may also reflect laboratory policies.

Our study relies on self-reported data describing the influence of direction of diagnosis; however, there is no reason to assume pathologists would incorrectly report their usual practice. We also did not compare the diagnostic accuracy of pathologists with more years of MSL interpretation to that of pathologists with specialized DP expertise. However, a recent analysis, based on the same group of pathologists, showed a significantly lower percentage of malpractice suits among those with DP fellowship training or board certification,24 suggesting greater accuracy among those with specialized training. Our sample of pathologists, although arising from diverse settings and geographic areas may not generalize to the population of US pathologists. However, we found no differences between pathologists who agreed to enroll in our study and those who did not. We also cannot be certain that the direction of influence reported by pathologists reflects their actual practice. Strengths of our study include the diversity of the study sample, which represents pathologists in 10 states, a 69% response rate among eligible participants, exceeding the national standard for physician surveys,25 the detailed information gathered on the survey, and the quality of the analysis.

Our findings underscore the complexity inherent in the subjective process of histological diagnosis of MSLs, revealing possible explanations for diagnostic discordance rates for melanoma and illustrating the potential for misclassification errors, with potentially substantial public health impacts, when identifying patient populations diagnosed with this maligancy. Future research may be helpful to assess the potential role of additional pathologist characteristics and other factors not evaluated here, as well as to determine whether the factors identified in this study may result in biases associated with the interpretation of more recent, ‘objective’ diagnostic technology, including immunohistochemical markers, FISH, CGH, and gene expression profiling.

References

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ et al, Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–6206.

Azzola MF, Shaw HM, Thompson JF et al, Tumor mitotic rate is a more powerful prognostic indicator than ulceration in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma: an analysis of 3661 patients from a single center. Cancer 2003; 97: 1488–1498.

Barnhill RL, Fine JA, Roush GC et al, Predicting five-year outcome for patients with cutaneous melanoma in a population-based study. Cancer 1996; 78: 427–432.

Breslow A . Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg 1970; 172: 902–908.

Jemal A, Devesa SS, Hartge P et al, Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence among whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 678–683.

Lasithiotakis K, Leiter U, Meier F et al, Age and gender are significant independent predictors of survival in primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2008; 112: 1795–1804.

McGovern VJ, Shaw HM, Milton GW . Prognosis in patients with thin malignant melanoma: influence of regression. Histopathology 1983; 7: 673–680.

Printz C . Spontaneous regression of melanoma may offer insight into cancer immunology. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 1047–1048.

Burton AL, Gilbert J, Farmer RW et al, Regression does not predict nodal metastasis or survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Am Surg 2011; 77: 1009–1013.

Garbe C . Partial histological tumor regression in primary melanoma as protective factor for lymph node micrometastasis. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 1291–1292.

Clark WH Jr., Elder DE, Guerry Dt et al, Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81: 1893–1904.

Bertolli E, de Macedo MP, Pinto CAL et al, Evaluation of melanoma features and their relationship with nodal disease: the importance of the pathological report. Tumori 2015; 101: 501–505.

Cintolo JA, Gimotty P, Blair A et al, Local immune response predicts survival in patients with thick (t4) melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 3610–3617.

Kvaskoff M, Pandeya N, Green AC et al, Solar elastosis and cutaneous melanoma: a site-specific analysis. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 2900–2911.

Thomas NE, Kricker A, From L et al, Associations of cumulative sun exposure and phenotypic characteristics with histologic solar elastosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 2932–2941.

Smoller BR . Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol 2006; 19: S34–S40.

Berwick M, Armstrong BK, Ben-Porat L et al, Sun exposure and mortality from melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 195–199.

Heenan PJ, English DR, Darcy C et al, Survival among patients with clinical stage-I cutaneous malignant-melanoma diagnosed in Western Australia in 1975/1976 and 1980/1981. Cancer 1991; 68: 2079–2087.

Ribero S, Osella-Abate S, Sanlorenzo M et al, Favourable prognostic role of regression of primary melanoma in AJCC stage I-II patients. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 1240–1245.

Piepkorn M, Barnhill R . Prognostic factors in cutaneous melanoma. In: Barnhill RL, Piepkorn M, Busam KJ (eds). Pathology of Melanocytic Nevi and Melanoma, 3rd edn. Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, 2014, pp 569–602.

Meier F, Will S, Ellwanger U et al, Metastatic pathways and time courses in the orderly progression of cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2002; 147: 62–70.

Tas F . Metastatic behavior in melanoma: timing, pattern, survival, and influencing factors. J Oncol 2012; 2012: 647684.

Reed JA, Shea CR . Lentigo maligna: melanoma in situ on chronically sun-damaged skin. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2011; 135: 838–841.

Carney PA, Frederick PD, Reisch LM et al, How concerns and experiences with medical malpractice affect dermatopathologists' perceptions of their diagnostic practices when interpreting cutaneous melanocytic lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 74: 317–324.

Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA . Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 1129–1136.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 CA151306.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Laboratory Investigation website

The authors surveyed 207 U.S. pathologists to determine whether patient age and tumor characteristics influenced the direction of their diagnosis when interpreting melanocytic skin lesions. The majority (54.6%) reported influence toward a less severe diagnosis by patient age <30, and toward a more severe diagnosis by patient age >70 (58.6%), tumor regression (71.0%), and solar elastosis (57.0%).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Titus, L., Barnhill, R., Lott, J. et al. The influence of tumor regression, solar elastosis, and patient age on pathologists’ interpretation of melanocytic skin lesions. Lab Invest 97, 187–193 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2016.120

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2016.120