Abstract

Major basic protein (MBP), the predominant cationic protein of human eosinophil specific granules, is stored within crystalloid cores of these granules. Secretion of MBP contributes to the immunopathogenesis of varied diseases. Prior electron microscopy (EM) of eosinophils in sites of inflammation noted losses of granule cores in the absence of granule exocytosis and suggested that eosinophil granule proteins might be released through piecemeal degranulation (PMD), a secretory process mediated by transport vesicles. Because release of eosinophil granule-derived MBP through PMD has not been studied, we evaluated secretion of this cationic protein by human eosinophils. Intracellular localizations of MBP were studied within nonstimulated and eotaxin-stimulated human eosinophils by both immunofluorescence and a pre-embedding immunonanogold EM method that enables optimal epitope preservation and antigen access to membrane microdomains. In parallel, quantification of transport vesicles was assessed in eosinophils from a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). Our data demonstrate vesicular trafficking of MBP within eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils. Vesicular compartments, previously implicated in transport from granules to the plasma membrane, including large vesiculotubular carriers termed eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs), were found to contain MBP. These secretory compartments were significantly increased in numbers within HES eosinophils. Moreover, in addition to granule-stored MBP, even unstimulated eosinophils contained appreciable amounts of MBP within secretory vesicles, as evidenced by immunonanogold EM and immunofluorescent colocalizations of MBP and CD63. These data suggest that eosinophil MBP, with its multiple extracellular activities, can be mobilized from granules by PMD into secretory vesicles and both granule- and secretory vesicle-stored pools of MBP are available for agonist-elicited secretion of MBP from human eosinophils. The recognition of PMD as a secretory process to release MBP is important to understand the pathological basis of allergic and other eosinophil-associated inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Classical functions of eosinophils are based on their effector responses involving secretory processes that mobilize and release their preformed pools of granule-stored cationic proteins, including major basic protein (MBP), the most abundant eosinophil granule cationic protein. The functions of MBP in mediating cytotoxicity and allergic disorders such as asthma are long recognized. In addition to being cytotoxic to a variety of tissues, including heart, brain and bronchial epithelium, MBP increases smooth muscle reactivity by causing dysfunction of vagal muscarinic M2 receptors, which may contribute to the development of airway hyperreactivity, a cardinal feature of asthma (reviewed in References 1–3). MBP is also a potent helminthotoxin.4, 5, 6

Within eosinophils, MBP is synthesized first as a precursor pro-MBP protein that is proteolytically processed within cytoplasmic granules into 14 kDa MBP. MBP is then packaged and stored within the often electron dense crystalline cores of eosinophil secretory ‘specific’ granules.7, 8 Early transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies of lesional eosinophils in Crohn's disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) noted that eosinophils lost their electron dense cores9, 10, 11 and suggested that eosinophil granule core-derived MBP might be released by a mechanism not involving wholesale granule fusion at the plasma membrane. A candidate mechanism suggested by these early reports was that eosinophil granule proteins might be mobilized from within intracellular granules into vesicles that traffic to and release extracellularly at the cell surface, a process termed piecemeal degranulation (PMD).12, 13, 14 Recent studies from our laboratory demonstrate the selective secretion by PMD of eosinophil granule-stored cytokines, such as IL-4.15, 16, 17 Based principally to date on ultrastructural observations of eosinophil granules, PMD has been suggested to be involved in the release of products from activated eosinophils in a range of human diseases including allergic inflammation.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In full support of these earlier studies, we now demonstrate increased numbers of large vesiculotubular carriers termed eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs), previously determined to function in cargo transport from granules to the plasma membrane,25 in the absence of granule–granule or granule–plasma membrane fusion events in eosinophils from a patient with HES. Recently, we detected the presence of MBP in transport vesicles within human eosinophils activated in vitro with the eosinophil-active chemokine, eotaxin (CCL-11).25 These results, in concert with prior observations of the losses of MBP-containing cores within granules of eosinophils in sites of inflammation, provided inferential indications about mechanisms underlying MBP release. Although MBP is extensively detected in inflammatory sites,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 little is known about whether this eosinophil granule protein can be secreted by PMD.

With pre-embedding immunonanogold electron microscopy (EM) for precise epitope preservation and secondary antibody (Ab) Fab fragments specifically conjugated with very small gold particles (1.4 nm) as a probe, we now demonstrate MBP in vesicles surrounding and extending from granules and beneath the plasma membrane within human eosinophils stimulated with eotaxin. Distinct vesicular compartments, including EoSVs,25 were also labeled with anti-MBP antibodies. Furthermore, our findings using immunonanogold EM and immunofluorescent colocalizations of MBP and CD63, a marker of eosinophil granule limiting membranes,32 indicate that secretory vesicles constitute substantial extragranular pools of MBP even within unstimulated human eosinophils. Our findings provide new insights into the intracellular mechanisms mediating secretion of eosinophil granule-derived proteins, corroborate previous evidence of PMD as a predominant mechanism of eosinophil secretion in patients with eosinophilia19, 20, 21, 24 and identify, for the first time, PMD as a secretory process to release the granule-derived cationic protein, MBP, from human eosinophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eosinophil Isolation, Stimulation and Viability

Granulocytes were isolated from the blood of different healthy donors and from one patient with HES (negative for Fip1-like 1/platelet-derived growth factor-α mutation). Eosinophils from the former donors were enriched and purified by negative selection using human eosinophil enrichment cocktail (StemSep; StemCell Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) and the MACS bead procedure (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), as described,33 with the exception that hypotonic red blood cell (RBC) lysis was omitted to avoid any potential for RBC lysis to affect eosinophil function. Experiments were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Committee on Clinical Investigation, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Purified eosinophils (106 cells per ml) were stimulated with recombinant human eotaxin (100 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in RPMI-1640 medium plus 0.1% ovalbumin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) or medium alone at 37°C, for 1 h. Eosinophil viability and purity were greater than 99% as determined by ethidium bromide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) incorporation and cytocentrifuged smears stained with HEMA 3 stain kit (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX, USA), respectively.

Antibody Reagents

Anti-human mouse IgG1 CD63 (clone H5C6) and irrelevant isotype control monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for flow cytometry (5 μg/ml) and fluorescence (5 μg/ml) and EM (2 μg/ml) immunodetection studies. Secondary Ab for CD63 immunofluorescence in eosinophils was an anti-mouse Alexa 594 prebound to the primary Ab using Zenon labeling as per the manufacturer's directions (Molecular Probes) and for CD63 flow cytometry of isolated granules was a goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Ab (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch). The secondary Ab for immunoEM was an affinity-purified goat anti-mouse Fab fragment conjugated to 1.4 nm gold (1:100, Nanogold; Nanoprobes, Stony Brook, NY, USA). Abs for MBP detection in eosinophils by immunofluorescence (5 μg/ml for single staining, 2.5 μg/ml for dual staining) and immunoEM (5 μg/ml) were monoclonal mouse anti-human MBP (clone AHE-2) and irrelevant isotype IgG1 control (BD Pharmingen). Secondary Ab for MBP immunofluorescence in single-stain experiments was anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes), and for dual staining anti-MBP mAb was detected with anti-mouse Alexa 488 using Zenon-labeling kits (Molecular Probes). Mouse anti-human MHC class I (HLA-ABC, clone G46-2.6, 14 μg/ml; BD Pharmingen) FITC-conjugated mAb was used with the respective FITC-conjugated IgG control mAb.

Subcellular Fractionation

Eosinophils were resuspended in disrupting buffer as described,34 supplemented with 5 μg/ml dithiothreitol and subjected to nitrogen cavitation (Parr, Moline, IL, USA) under pressure of 600 p.s.i. (10 min). Postnuclear supernatants, recovered after centrifugation (400 g, 10 min), were ultracentrifuged (1 00 000 g, 1 h at 4°C) in linear Accudenz or isotonic Optiprep (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway) gradients (0–45% in disrupting buffer without protease inhibitors). Fractions (20 × 0.5 ml) were collected with a peristaltic pump. Eosinophil granules and EoSVs were isolated, as previously described.16

Preparation of Cells and Subcellular Fractions for EM

Purified eosinophils and their isolated, purified subcellular fractions were immediately fixed in a mixture of freshly prepared aldehydes (1% paraformaldehyde (PFO) and 1.25% glutaraldehyde) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h, at room temperature (RT), washed in the same buffer and centrifuged at 1500 g for 1 min. Samples were then resuspended in molten 2% agar in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and quickly recentrifuged. Resultant agar pellets were kept in the same buffer at 4°C for further processing. For immunoEM, cells or subcellular fractions were fixed in fresh 4% PFO in 0.02 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 (CD63 labeling) or 1% PFO and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4 (MBP labeling), for 30 min at RT, washed in PBS and embedded in molten 2% agar, as above. Pellets were immersed in 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C, embedded in OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN, USA), and stored in −180°C liquid nitrogen for subsequent use.

Conventional TEM

Agar pellets containing either intact eosinophils or their isolated eosinophil granules were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in Sym-Collidine buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at RT. After washing with sodium maleate buffer (pH 5.2), pellets were stained en bloc in 2% uranyl acetate in 0.05 M sodium maleate buffer (pH 6.0) for 2 h at RT and washed in the same buffer as above before dehydration in graded ethanols and infiltration and embedding with a propylene oxide-Epon sequence (Eponate 12 Resin; Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA). After polymerization at 60°C for 16 h, thin sections were cut using a diamond knife on an ultramicrotome (Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA). Sections were mounted on uncoated 200-mesh copper grids (Ted Pella) before staining with lead citrate and viewed with a transmission electron microscope (CM 10; Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) at 60 kV. For EoSV quantification in granule fractions, electron micrographs from different subcellular fractionations (n=3) were randomly taken at × 21 000 and analyzed at the final magnification of × 58 000. A total of 941 EoSVs were counted. To quantify the total number of EoSVs within eosinophils from the HES donor, we randomly obtained 35 electron micrographs of cell sections showing the entire cell profile and nucleus at × 12 000 and analyzed these at a final magnification of × 33 000. Data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test (P<0.05).

ImmunoEM

Pre-embedding immunolabeling was carried out before standard EM processing (dehydration, infiltration, resin embedding and resin sectioning). Pre-embedding immunoEM optimizes antigen preservation and is more sensitive to detect small molecules than post-embedding labeling that is carried out after conventional EM processing. Moreover, to reach antigens at membrane microdomains such as small vesicles, we used labeling with very small (1.4 nm) gold particles (Nanogold). Immunonanogold was performed on cryostat 10 μm sections mounted on glass slides. All steps were carried out at RT as before,16 and modified as follows: cells or EoSVs isolated by subcellular fractionation were incubated in a mixture of PBS and bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA buffer; 0.02 M PBS plus 1% BSA) containing 0.1% gelatin (20 min) followed by PBS-BSA plus 10% normal goat serum (NGS) and incubated with primary Ab (1 h). After blocking with PBS-BSA plus NGS (30 min), cells were incubated with secondary Ab (1 h), washed in PBS-BSA, postfixed in 1% glutaraldehyde (10 min) and incubated with HQ silver enhancement solution (Nanoprobes) (10 min). Cells or fractions in cryostat sections were immersed in 5% sodium thiosulfate (5 min), postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in distilled water (10 min), stained with 2% uranyl acetate in distilled water (5 min), embedded in Eponate and thin sectioned as described.35 Two controls were performed: (1) primary Ab was replaced by an irrelevant Ab and (2) primary Ab was omitted. Specimens were examined as described for conventional TEM. Electron micrographs from different experiments (n=4) were randomly taken at magnifications of × 12 000 to × 40 000 to study the entire cell profile and vesicle features. A total of 195 electron micrographs were evaluated.

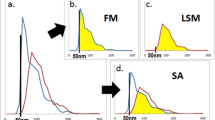

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Eosinophils (15 × 106 cells per ml) were gently mixed at 37°C with a low-gelling temperature 1.25% agarose (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) in a 3:1 ratio (cells/agarose) and carefully spread onto slides (20 μl per slide). After agarose was solidified, a perfusion chamber (CoverWell; Grace Bio-Labs, Bend, OR, USA) was affixed over cells and medium added to maintain moisture. After several minutes to allow for cell attachment and spreading, chambers were removed and cells fixed in 2% PFO for 5 min at RT. Slides were then washed with Ca2+/Mg2+ free Hanks-buffered salt solution (HBSS−/−) alone, followed by a 5 min incubation in permeabilization solution (0.1% saponin, 5% milk, 1% NGS in HBSS−/−). For MBP single-staining experiments, permeabilized cells were incubated with primary Ab for 1 h, washed and incubated with secondary Ab for 45 min at RT. For dual labeling with anti-MBP and anti-CD63, permeabilized cells were incubated with Zenon-labeled primary Abs for 45 min at RT. Cells were washed (2 × 10 min) before drying and coverslipping. Analyses were performed by both phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

Deconvolution Microscopy

Fluorescence images were acquired using a Retiga EXi cooled CCD camera (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) coupled to a Provis AX-70 Olympus microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY, USA) and an UPlanApo objective (100 × 1.35). The microscope, Z-motor drive, shutters and camera were controlled by IPLab 3.6 for Mac (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA, USA). Acquired stacks were further processed for deconvolution with Volocity 2.6 (Improvision, Lexington, MA, USA).

Flow Cytometry

Nonpermeabilized granules were incubated either with primary FITC-conjugated Ab (45 min) or primary (1 h) and then FITC-conjugated secondary (15 min) Abs on ice in the absence of granule fixation. After staining, granules were fixed in buffer containing 2% PFO without methanol (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 5 min. Flow cytometric data, acquired using a FACScan with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), were analyzed by comparisons of mean fluorescent intensities of unimodal histograms.

RESULTS

Intracellular Compartmentalization of MBP in Unstimulated Human Eosinophils

With eosinophils isolated from normal donors and prepared for immunofluorescent staining on air-dried cytospins, punctate (luminal) granule staining was observed for MBP (Figure 1a), as previously reported with this anti-MBP mAb.34 In contrast, when eosinophils were kept moist in an agarose matrix that combines cell labeling with preservation of cell morphology, MBP staining was closely associated with granules and often exhibited circumferential, perigranular staining (Figure 1b). To further evaluate the perigranular MBP staining, we utilized deconvolution microscopy of eosinophils stained for both MBP and CD63 (Figure 1c), a tetraspanin transmembrane protein that is localized at the cytoplasmic face of eosinophil granule membranes as evidenced by EM immunonanogold (Figure 1d) and by flow cytometry showing anti-CD63 on the membranes of eosinophil granules isolated by subcellular fractionation (not shown).25, 32 Deconvolution microscopy revealed CD63 granule membrane labeling, often associated with MBP labeling peripheral to the CD63 ring (Figure 1c). Control cells assayed with an irrelevant Ab were negative. The two different MBP-labeling patterns observed in the present study can be explained by the use of different cell preparation methodologies. Cell drying before labeling favors Ab access to the compact granule cores, but likely eliminates MBP labeling on other labile intracellular sites. On the other hand, these sites are detected only when the cells are kept moist, although in this case the antibodies cannot access granule cores.

Major basic protein (MBP) and CD63 colocalize within human unstimulated eosinophils. (a) When eosinophils were allowed to dry in cytospin preparations, MBP immunodetection (green fluorescence) was observed within specific granules. A single eosinophil is shown in phase contrast (ai), fluorescence microscopy (aii) and an overlay of these two images (aiii). (b) Fluorescence (bi) and phase contrast (bii) microscopy of an identical field of eosinophils kept in a wet agarose preparation show green MBP labeling often circumferentially peripheral to specific granules. (ci) MBP (green) and CD63 (red) colocalizations, evaluated by deconvolution microscopy, reveal both fluorescent sites marginal to cytoplasmic granules, with MBP labeling often peripheral to membrane-bound CD63 (arrow). cii is a higher magnification of the boxed area in ci. (d) Immunogold electron microscopy demonstrates CD63 labeling primarily on the cytoplasmic surface of eosinophil granule limiting membranes. Fluorescence images were acquired using a Retiga EXi cooled CCD camera coupled to a Provis AX-70 Olympus microscope and an UPlanApo objective (100 × 1.35). Acquired stacks were further processed for deconvolution with the software Volocity 2.6. Fluorochromes used were Alexa 488 (MBP) and Alexa 594 (CD63). The electron micrograph was obtained on a CM 10 (Philips) transmission electron microscope at 60 kV. Bar, 6 μm (a and b); 5 μm (ci); 2 μm (cii); 400 nm (d). Gr, specific granules.

Vesicular Transport of MBP in Activated Eosinophils

To ascertain the intracellular localizations of MBP within activated eosinophils, we utilized immunonanogold EM protocols likely to preserve extragranular membranous organelles (ie, vesicles) and to detect antigenic epitopes.16 With pre-embedding immunonanogold EM for epitope preservation and a secondary Fab Ab fragment conjugated to very small gold particles to access possible vesicular domains positive for MBP, MBP was immunolocalized within eosinophils stimulated with an agonist, eotaxin, that elicits mobilization of eosinophil granule proteins.16 MBP was detected within granule matrices (Figure 2ai arrows, ) and within granules with apparently mobilized crystalline cores (Figure 2a and d). Moreover, MBP was present within vesicles attached to or surrounding the surface of emptying granules (Figures 2aii, 2b and 3c). Vesicles containing MBP were distributed around mobilized granules (Figure 2b), in the cytoplasm and beneath the cell surface (Figures 2c and 3a). MBP-positive vesicles fused with the plasma membrane (Figures 2c and 3b). Of note, the MBP-positive vesicular system was associated with secretory pathways operating from eosinophil granules and not with a synthetic route from the trans-Golgi network, which was rarely labeled for MBP (not shown). Control cells in which the primary Ab was replaced by an irrelevant Ab were negative (not shown). Altogether, these findings indicate that in activated eosinophils granule-derived MBP can be segregated into secretory vesicles and released through PMD.

Major basic protein (MBP) is localized to specific granules and cytoplasmic vesicles in human eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils. Immunonanogold electron microscopy revealed MBP-positive vesicles surrounding (a and b) and arising (c) from granules undergoing depletion of their contents. (aii) is the boxed area of (ai) and shows a tubular vesicle (arrowheads) at the surface of a specific granule. Note that MBP is present in the granule and in the attached vesicle. In (b), a pool of vesicles around a secretory granule is labeled for MBP. Observe that (aii) and (b) show specific granules in progressive stages of content emptying, characterized by reduced electron density. In (c), a linear array of small, MBP-positive vesicles bud from a granule surface into the cell surface. The inset shows a vesicle fused with the plasma membrane at higher magnification. In (d), a granule, which demonstrates its disarranged core and matrix, is densely labeled for MBP. A similar image is seen at low magnification in ai (arrows). Bar, 800 nm (ai); 300 nm (aii and c); 500 nm (b and d). Gr, specific granules.

Large tubular carriers actively transport MBP. (a–c) Eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs; arrows) are observed in the cytoplasm of activated eosinophils by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) after immunonanogold labeling for MBP. Vesicles are seen beneath the plasma membrane in the cytoplasm (a), fused with the plasma membrane (b) and attached to an enlarged partially empty granule (c), typically indicative of PMD. In (d), EoSVs, isolated by subcellular fractionation from unstimulated eosinophils, are densely labeled for MBP. Note that MBP is preferentially localized within the vesicle lumen. Eosinophils were stimulated by eotaxin as described in Materials and methods section. Bar, 400 nm (a); 230 nm (b); 250 nm (c); 200 nm (d). Gr, specific granules; N, nucleus.

Intracellular Transport of MBP is Mediated by Large Vesiculotubular Carriers

MBP-containing vesicles included both spherical small vesicles (Figure 2c) and morphologically distinct, large vesiculotubular EoSV compartments (Figure 3). EoSVs, recently associated with eosinophil secretory pathways, represent vesiculotubular pathways for transport of eosinophil granule products for their rapid extracellular release at the plasma membrane.16, 36 The lumina of EoSVs consistently labeled for MBP (Figure 3). EM quantitative analyses revealed up to 39 gold particles per vesicle section. EoSVs were distributed in the cytoplasm, beneath plasma membranes (Figure 3a) and at times fused with plasma membranes (Figure 3b), and attached to secretory granules undergoing PMD in in vitro eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils (Figure 3c).

Because EoSVs are prominently formed within in vitro-activated eosinophils36, 37 and these vesicles were extensively labeled for MBP, we next investigated the distribution of EoSVs within otherwise unstimulated eosinophils from a patient with HES. This disorder is characterized by increased numbers of activated eosinophils in the blood and tissues38, 39, 40 and was previously associated with losses of specific granule cores.11 Our EM quantitative analyses found that the total number of EoSVs in HES eosinophils was significantly higher compared to eosinophils from healthy donors (35.4±11.4 per section for HES vs 21.3±4.9 for normal eosinophils (mean±s.e.m.), n=35 cells, P<0.05) (Figure 4a). In the eosinophils of a HES subject, EoSVs were distributed in the cytoplasm and were clearly observed in contact with granules showing disassembled cores (Figures 4b and 5). Granule–granule or granule–plasma membrane fusion events were not observed within HES eosinophils (Figure 5).

Eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs) are significantly increased within HES eosinophils. (a) Significant increases in EoSV numbers are observed within eosinophils from a patient with HES compared to normal donors (*P<0.05). (bi and bii) The boxed area shows EoSVs (arrows), with typical morphology, close or associated with an emptying specific granule. A total of 958 EoSVs were counted in 35 cell sections showing the entire cell profile ad nucleus. Bar, 600 nm (bi); 250 nm (bii). Gr, specific granules; N, nucleus; HES, hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Ultrastructure of an eosinophil from a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. (ai) Specific granules (Gr) with typical crystalloid cores are observed together with enlarged granules with disassembled cores (boxed area in higher magnification in aii). Arrows indicate eosinophil sombrero vesicles (EoSVs). Bar, 800 nm (ai); 300 nm (aii). Gr, specific granules; LB, lipid body.

To corroborate a function for EoSVs in transporting MBP, we utilized subcellular fractionation16 to isolate EoSVs from unstimulated eosinophils. By immunonanogold EM, isolated EoSVs contained MBP (Figure 3d). As observed in intact eosinophils (Figure 2a–c), MBP was densely labeled within the tubular lumina of EoSVs (Figure 3d). These results provide new documentation that even within unstimulated human eosinophils MBP is found within secretory vesicles of eosinophils and document that large vesiculotubular carriers, a secretory compartment increased in patients with HES, can mediate transport of this cationic granule-derived protein.

Unstimulated Eosinophils Contain Pools of MBP-Loaded Cytoplasmic Vesicles

Although activation of eosinophils leads to mobilization of granule-derived MBP into secretory vesicles, several findings, noted above, indicate that even unstimulated eosinophils contain extragranular, vesicular pools of MBP. For instance, these vesicular pools were imaged both by immunofluorescence as labeling circumferential to specific granules in wet preparations (agarose matrix) (Figure 1b and c) and by immunonanogold EM as a collar of MBP-loaded vesicles (Figure 6a and b). The presence of pools of MBP-positive vesicles in unstimulated eosinophils was confirmed by immunonanogold EM after vesicle isolation by subcellular fractionation (Figure 3d).

A major pool of MBP-loaded vesicles is tightly associated with secretory granules in unstimulated eosinophils. (a) Immunonanogold electron microscopy reveals MBP labeling within and around specific granules in an unstimulated eosinophil. (b) In higher magnification, labeling around granules is imaged as a consistent pool of MBP-positive vesicles. Labeling is observed in both round small and large vesiculotubular (arrowheads) carriers. Note that the vesicles are closely associated with the granule. (c) A cluster of free granules released from a disrupted eosinophil after double immunolabeling for CD63 and MBP shows fluorescence for MBP (green) peripheral to CD63 (red) in some granules. Fluorescence image was acquired using a Retiga EXi cooled CCD camera coupled to a Provis AX-70 Olympus microscope and an UPlanApo objective (100 × 1.35). Fluorochromes used were Alexa 488 (MBP) and Alexa 594 (CD63). Bar, 600 nm (a); 250 nm (b); 2 μm (c). Gr, specific granules; N, nucleus.

We further evaluated associations between MBP-positive vesicles and specific granules in unstimulated eosinophils. Using the agarose matrix system, we analyzed free granules released from mechanically disrupted unstimulated eosinophils after double immunolabeling for CD63 and MBP. Clusters of free eosinophil granules evaluated at high magnification exhibited granules with the same MBP/CD63 pattern of labeling as observed in intact cells, ie, with membrane CD63 labeling associated with MBP labeling peripheral to CD63 (Figure 6c). This indicates that MBP-loaded vesicles are associated with and likely derived from eosinophil-specific granules. TEM of subcellularly isolated granules,25 identified EoSVs, with their typical morphology and size (150–300 nm), in granule-enriched fractions (Figure 7a). These subcellular fractions were free of other organelles and exhibited granules with intact surrounding membranes. EM analyses were performed using 48 electron micrographs randomly taken from denser granule and supragranule eosinophil subcellular fractionations (n=3) isolated from isotonic Optiprep gradients for optimal membrane preservation. A total of 941 EoSVs were counted. Our analyses indicated that part of this EoSV population (38%) was attached to the granule delimiting membrane in isolated granules (Figure 7a and b), as seen in intact cells (Figure 3c) and a larger fraction (62%) was not visibly attached to granules. Of note, granules isolated by subcellular fractionation did not express contaminating plasma membrane or endosomal MHC class I protein as assessed by flow cytometry after staining with anti-MHC I mAb (data not shown). Taken together, our findings identify cytoplasmic vesicles, derived from eosinophils granules, as intracellular sites of MBP localization in unstimulated eosinophils.

Ultrastructure of isolated eosinophil granules. (ai and bi) Transmission electron microscopy of a granule-enriched fraction isolated by subcellular fractionation shows typical EoSVs, the lumens of which are highlighted in pink in (aii and bii). EoSVs are imaged as open, curved, tubular-shaped structures. EoSVs are seen around and in close association with isolated granules. Granules were isolated and fixed for optimal membrane preservation as described in Materials and methods section. Bar, 250 nm (a and b). Gr, specific granules.

DISCUSSION

Release of granule-derived MBP by human eosinophils is a key event in the pathogenesis of allergic airway diseases, such as rhinitis and asthma, and other eosinophil-mediated diseases; but little is known about the cellular mechanisms of MBP release from eosinophils. Granule-stored products are released from eosinophils through different modes; (1) classical exocytosis by which granules release their entire contents following granule fusion with the plasma membrane, including compound exocytosis, which also involves intracellular granule–granule fusion before extracellular release; (2) PMD, which is mediated through vesicular transport and secretion of granule-derived proteins; and (3) cytolysis, which involves the extracellular deposition of intact granules upon lysis of the cell (reviewed in References 41–43). PMD is likely the predominant mode of secretion from eosinophils in different human diseases;18, 20, 22, 23 and both PMD and cytolysis are reported to occur in the airway lumen and tissues.21, 44, 45 Of note, one eosinophil granule-derived protein, eosinophil cationic protein, has been documented in subcellular fractionations studies to be localized in cytosolic vesicles isolated from eosinophils of allergic patients specifically during their seasonal allergen exposures.19 During eosinophil development, MBP is sequentially synthesized, processed and then packaged within the crystalline cores of eosinophil-specific granules.7, 46 Despite observed extracellular MBP deposition, granule-mobilized MBP had not previously been detectable within eosinophil cytoplasmic vesicles in association with eosinophil-associated diseases. For instance, in human atopic dermatitis, although extracellular deposition of MBP was observed in parallel with ultrastructural changes within eosinophils indicative of PMD (granule core lucencies and vesicles budding from granules), for likely technical reasons, MBP was not demonstrable within eosinophil secretory vesicles.28 Prior MBP localization by immunoEM has been evaluated only by post-embedding techniques,28, 47 ie, when labeling is carried out after dehydration and resin embedding, steps that may affect epitope preservation in membrane microdomains. In addition, these techniques used larger sized gold particles (around 15 nm) conjugated to polyclonal Abs28, 47 that might also compromise subcellular localization of MBP in vesicular compartments. In contrast, our findings used a pre-embedding technique combined with a smaller Fab secondary Ab fragment conjugated with very small gold particles to facilitate access to vesicles. These immunonanogoldEM techniques were complemented with additional experimental approaches.

To evaluate potential PMD-mediated release of granule MBP from human eosinophils, we studied eosinophils from normal and eotaxin-activated human eosinophils. Eotaxin stimulation of eosinophils in vitro elicits gross alterations in granule ultrastructure typical of PMD,25, 37 as well recognized to occur within activated eosinophils in vivo,19, 21 including the mobilization of granule core and/or matrix contents. We found that both unstimulated and in vitro-eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils demonstrated vesicular trafficking of MBP. A prominent system of secretory vesicles from specific granules to plasma membrane was consistently labeled for MBP. This important process has likely been previously underestimated because of technical issues—inadequate preservation of vesicles and/or inability of Ab access to them. In fact, using different technical approaches for cell preparation before labeling, we were able to detect two different MBP labeling patterns. Our present immunofluorescent findings showed that extragranular sites for MBP can be detected only in wet preparations of eosinophils (Figure 1). MBP detection within granules by immunofluorescence depended on cell drying, which favors Ab access to the compacted crystalline core, but likely eliminates the vesicular pool. It is important to note that although our EM approach using pre-embedding labeling with mAbs strongly favored vesicle labeling, it did not enable optimal Ab access to the intact crystalline cores. Granules showing different degrees of core disarrangement, a process that seems fundamental for MBP release by PMD, were densely labeled for this cationic protein.

MBP was consistently detected in large tubular vesicles (EoSVs) (Figure 3), a vesicular system actively formed when eosinophils are stimulated with classical eosinophil agonists.16 Moreover, we demonstrate that the total numbers of EoSVs are significantly increased within HES eosinophils (Figure 4a), which are typically activated38 compared to normal donors. These findings are important because they would explain the reason for the loss of electron dense cores (enriched in crystallized MBP) observed in tissue eosinophils from a range of disorders, such as Crohn's disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and HES.9, 10, 11 In fact, deposition of MBP can be demonstrated in affected tissues of patients with HES48 and vesicular trafficking is likely involved in this secretory mechanism.

Increasing evidence has shown that large tubular carriers provide an additional mechanism to rapidly transport material between membranes in different secretory pathways and are also responsible for moving the bulk of the secretory traffic between distant compartments.49, 50 In eosinophils, EoSVs may be fundamental for the diversity of proteins that need to be rapidly transported from within these cells.36 Interestingly, MBP was observed preferentially within the lumen of EoSVs (Figure 3) in contrast to vesicle membrane-bound localization of eosinophil cytokines, such as IL-4,16 a mechanism mediated by cognate, membrane-inserted receptors, as recently demonstrated by our group.17 The present finding showing preferential MBP labeling within vesicle lumina instead of at vesicle membranes provides more evidence for the occurrence of distinct cellular mechanisms involved in the mobilization of specific proteins from eosinophil granules. In fact, it is now apparent that eosinophils have a remarkable capacity to select proteins to be secreted from their cytoplasmic granules,25, 41 an event that underlies their multiple functions. An understanding of the intrinsic complexity of the eosinophil secretory pathway is beginning to emerge.

Rapid release of MBP may involve the presence of small storage/transient MBP sites (vesicular pools) in the cytoplasm as identified, for the first time, in the present work in unstimulated eosinophils (Figure 1). These extragranular sites appear to be relevant for the rapid release of small concentrations of MBP under cell activation without immediate disarrangement of the intricate crystalline cores within eosinophil-specific granules. This is important because it may underlie eosinophil functions as an immunoregulatory cell. Indeed, the eosinophil functions as a regulator of local immune and inflammatory responses has increasingly been appreciated (reviewed in References 51–53); and MBP, in addition to being a recognized molecule for defense against parasites, seems to be involved in the regulation of cytokine responses.54

We also demonstrated that MBP-positive vesicles, including a large number of EoSVs, are tightly associated with specific granules. This finding supports our previous EM tomographic studies showing that EoSVs can arise from specific granules.16 Moreover, our present results shed more light on the understanding of the eosinophil secretory pathway. MBP-loaded vesicles maintain an effective interaction with the secretory granules and seem to be, at least in part, structurally linked to them. This interaction may be important for vesicular replenishment of MBP from granules. As noted here, the MBP-positive vesicular system was associated with a secretory pathway transporting MBP from eosinophil-specific granules and not with a synthetic route from the trans-Golgi network, which was rarely labeled for MBP.

In summary, our studies have identified vesicular trafficking in activated human eosinophils that directs transport of MBP from secretory granules to the cell surface. We also demonstrated a pool of secretory vesicles as an additional intermediate storage site for MBP in unstimulated eosinophils. The recognition of PMD as a secretory process to release MBP is important to understand the pathological basis of allergic and other eosinophil-associated inflammatory diseases.

References

Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP . The eosinophil. Annu Rev Immunol 2006;24:147–174.

Gleich GJ . Mechanisms of eosinophil-associated inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000;105:651–663.

Trivedi SG, Lloyd CM . Eosinophils in the pathogenesis of allergic airways disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2007;64:1269–1289.

Wassom DL, Gleich GJ . Damage to Trichinella spiralis newborn larvae by eosinophil major basic protein. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1979;28:860–863.

Hamann KJ, Barker RL, Loegering DA, et al. Comparative toxicity of purified human eosinophil granule proteins for newborn larvae of Trichinella spiralis. J Parasitol 1987;73:523–529.

Butterworth AE, Wassom DL, Gleich GJ, et al. Damage to schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni induced directly by eosinophil major basic protein. J Immunol 1979;122:221–229.

Popken-Harris P, Checkel J, Loegering D, et al. Regulation and processing of a precursor form of eosinophil granule major basic protein (ProMBP) in differentiating eosinophils. Blood 1998;92:623–631.

Egesten A, Alumets J, von Mecklenburg C, et al. Localization of eosinophil cationic protein, major basic protein, and eosinophil peroxidase in human eosinophils by immunoelectron microscopic technique. J Histochem Cytochem 1986;34:1399–1403.

Torpier G, Colombel JF, Mathieu-Chandelier C, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: ultrastructural evidence for a selective release of eosinophil major basic protein. Clin Exp Immunol 1988;74:404–408.

Dvorak AM . Ultrastructural evidence for release of major basic protein-containing crystalline cores of eosinophil granules in vivo: cytotoxic potential in Crohn's disease. J Immunol 1980;125:460–462.

Dvorak AM, Weller PF, Monahan-Earley RA, et al. Ultrastructural localization of Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (lysophospholipase) and peroxidase in macrophages, eosinophils, and extracellular matrix of the skin in the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Lab Invest 1990;62:590–607.

Dvorak AM, Ackerman SJ, Furitsu T, et al. Mature eosinophils stimulated to develop in human-cord blood mononuclear cell cultures supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-5. II. Vesicular transport of specific granule matrix peroxidase, a mechanism for effecting piecemeal degranulation. Am J Pathol 1992;140:795–807.

Dvorak AM, Estrella P, Ishizaka T . Vesicular transport of peroxidase in human eosinophilic myelocytes. Clin Exp Allergy 1994;24:10–18.

Dvorak AM . Piecemeal degranulation of basophils and mast cells is effected by vesicular transport of stored secretory granule contents. Chem Immunol Allergy 2005;85:135–184.

Bandeira-Melo C, Sugiyama K, Woods LJ, et al. Cutting edge: eotaxin elicits rapid vesicular transport-mediated release of preformed IL-4 from human eosinophils. J Immunol 2001;166:4813–4817.

Melo RCN, Spencer LA, Perez SAC, et al. Human eosinophils secrete preformed, granule-stored interleukin-4 (IL-4) through distinct vesicular compartments. Traffic 2005;6:1047–1057.

Spencer LA, Melo RCN, Perez SA, et al. Cytokine receptor-mediated trafficking of preformed IL-4 in eosinophils identifies an innate immune mechanism of cytokine secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:3333–3338.

Dvorak AM, Monahan RA, Osage JE, et al. Crohn's disease: transmission electron microscopic studies. II. Immunologic inflammatory response. Alterations of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, and the microvasculature. Hum Pathol 1980;11:606–619.

Karawajczyk M, Seveus L, Garcia R, et al. Piecemeal degranulation of peripheral blood eosinophils: a study of allergic subjects during and out of the pollen season. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;23:521–529.

Erjefalt JS, Greiff L, Andersson M, et al. Degranulation patterns of eosinophil granulocytes as determinants of eosinophil driven disease. Thorax 2001;56:341–344.

Ahlstrom-Emanuelsson CA, Greiff L, Andersson M, et al. Eosinophil degranulation status in allergic rhinitis: observations before and during seasonal allergen exposure. Eur Respir J 2004;24:750–757.

Caruso RA, Ieni A, Fedele F, et al. Degranulation patterns of eosinophils in advanced gastric carcinoma: an electron microscopic study. Ultrastruct Pathol 2005;29:29–36.

Qadri F, Bhuiyan TR, Dutta KK, et al. Acute dehydrating disease caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 induce increases in innate cells and inflammatory mediators at the mucosal surface of the gut. Gut 2004;53:62–69.

Shahana S, Bjornsson E, Ludviksdottir D, et al. Ultrastructure of bronchial biopsies from patients with allergic and non-allergic asthma. Respir Med 2005;99:429–443.

Melo RCN, Perez SAC, Spencer LA, et al. Intragranular vesiculotubular compartments are involved in piecemeal degranulation by activated human eosinophils. Traffic 2005;6:866–879.

Mueller S, Aigner T, Neureiter D, et al. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in oesophageal mucosa from adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis: a retrospective and comparative study on pathological biopsy. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:1175–1180.

Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kephart GM, et al. Striking deposition of toxic eosinophil major basic protein in mucus: implications for chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:362–369.

Cheng JF, Ott NL, Peterson EA, et al. Dermal eosinophils in atopic dermatitis undergo cytolytic degeneration. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99:683–692.

Dauer EH, Ponikau JU, Smyrk TC, et al. Airway manifestations of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: a clinical and histopathologic report of an emerging association. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2006;115:507–517.

Butterfield JH, Kephart GM, Banks PM, et al. Extracellular deposition of eosinophil granule major basic protein in lymph nodes of patients with Hodgkin's disease. Blood 1986;68:1250–1256.

Leiferman KM, Fujisawa T, Gray BH, et al. Extracellular deposition of eosinophil and neutrophil granule proteins in the IgE-mediated cutaneous late phase reaction. Lab Invest 1990;62:579–589.

Mahmudi-Azer S, Downey GP, Moqbel R . Translocation of the tetraspanin CD63 in association with human eosinophil mediator release. Blood 2002;99:4039–4047.

Bandeira-Melo C, Gillard G, Ghiran I, et al. EliCell: a gel-phase dual antibody capture and detection assay to measure cytokine release from eosinophils. J Immunol Methods 2000;244:105–115.

Lacy P, Mahmudi-Azer S, Bablitz B, et al. Rapid mobilization of intracellularly stored RANTES in response to interferon-gamma in human eosinophils. Blood 1999;94:23–32.

Feng D, Flaumenhaft R, Bandeira-Melo C, et al. Ultrastructural localization of vesicle-associated membrane protein(s) to specialized membrane structures in human pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. J Histochem Cytochem 2001;49:293–304.

Melo RCN, Spencer LA, Dvorak AM, et al. Mechanisms of eosinophil secretion: large vesiculotubular carriers mediate transport and release of granule-derived cytokines and other proteins. J Leukoc Biol 2008;83:229–236.

Melo RCN, Weller PF, Dvorak AM . Activated human eosinophils. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2005;138:347–349.

Ackerman SJ, Bochner BS . Mechanisms of eosinophilia in the pathogenesis of hypereosinophilic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2007;27:357–375.

Sheikh J, Weller PF . Advances in diagnosis and treatment of eosinophilia. Curr Opin Hematol 2009;16:3–8.

Hogan SP, Rosenberg HF, Moqbel R, et al. Eosinophils: biological properties and role in health and disease. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:709–750.

Moqbel R, Coughlin JJ . Differential secretion of cytokines. Sci STKE 2006;2006:pe26.

Erjefalt JS, Persson CG . New aspects of degranulation and fates of airway mucosal eosinophils. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:2074–2085.

Bandeira-Melo C, Weller PF . Mechanisms of eosinophil cytokine release. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2005;100:73–81.

Erjefalt JS, Andersson M, Greiff L, et al. Cytolysis and piecemeal degranulation as distinct modes of activation of airway mucosal eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;102:286–294.

Erjefalt JS, Greiff L, Andersson M, et al. Allergen-induced eosinophil cytolysis is a primary mechanism for granule protein release in human upper airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:304–312.

Peters MS, Rodriguez M, Gleich GJ . Localization of human eosinophil granule major basic protein, eosinophil cationic protein, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin by immunoelectron microscopy. Lab Invest 1986;54:656–662.

Dvorak AM, Furitsu T, Estrella P, et al. Ultrastructural localization of major basic protein in the human eosinophil lineage in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem 1994;42:1443–1451.

Tai PC, Ackerman SJ, Spry CJ, et al. Deposits of eosinophil granule proteins in cardiac tissues of patients with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Lancet 1987;1:643–647.

Simpson JC, Nilsson T, Pepperkok R . Biogenesis of tubular ER-to-Golgi transport intermediates. Mol Biol Cell 2006;17:723–737.

Luini A, Ragnini-Wilson A, Polishchuck RS, et al. Large pleiomorphic traffic intermediates in the secretory pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2005;17:353–361.

Jacobsen EA, Taranova AG, Lee NA, et al. Eosinophils: singularly destructive effector cells or purveyors of immunoregulation? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119:1313–1320.

Adamko DJ, Odemuyiwa SO, Vethanayagam D, et al. The rise of the Phoenix: the expanding role of the eosinophil in health and disease. Allergy 2005; 60:13–22.

Akuthota P, Wang HB, Spencer LA, et al. Immunoregulatory roles of eosinophils: a new look at a familiar cell. Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38: 1254–1263.

Specht S, Saeftel M, Arndt M, et al. Lack of eosinophil peroxidase or major basic protein impairs defense against murine filarial infection. Infect Immun 2006;74:5236–5243.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants AI020241, AI051645, and AI022571 to PFW; Interest Section and Faculty Development Awards to LAS from AAAAI; and CNPq and CAPES (Brazil) to RCNM, SACP and JSN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Melo, R., Spencer, L., Perez, S. et al. Vesicle-mediated secretion of human eosinophil granule-derived major basic protein. Lab Invest 89, 769–781 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2009.40

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2009.40

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Functions of tissue-resident eosinophils

Nature Reviews Immunology (2017)

-

Eosinophils in vasculitis: characteristics and roles in pathogenesis

Nature Reviews Rheumatology (2014)

-

Pre-embedding immunogold labeling to optimize protein localization at subcellular compartments and membrane microdomains of leukocytes

Nature Protocols (2014)

-

Visualizing aquatic bacteria by light and transmission electron microscopy

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (2014)

-

Morphology, cytochemistry and immunocytochemistry of the circulating granulocytes of the loggerhead sea turtle Caretta caretta

Comparative Clinical Pathology (2013)