Abstract

India has contributed immensely toward generating evidence on two key domains of newborn care: Home Based Newborn Care (HBNC) and community mobilization. In a model developed in Gadchiroli (Maharashtra) in the 1990s, a package of Interventions delivered by community health workers during home visits led to a marked decline in neonatal deaths. On the basis of this experience, the national HBNC program centered around Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) was introduced in 2011, and is now the main community-level program in newborn health. Earlier in 2004, the Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI) program was rolled out with inclusion of home visits by Anganwadi Worker as an integral component. IMNCI has been implemented in 505 districts in 27 states and 4 union territories. A mix of Anganwadi Workers, ASHAs, auxiliary nursing midwives (ANMs) was trained. The rapid roll out of IMNCI program resulted in improving quality of newborn care at the ground field. However, since 2012 the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare decided to limit the IMNCI program to ANMs only and leaving the Anganwadi component to the stewardship of the Integrated Child Development Services. ASHAs, the frontline workers for HBNC, receive four rounds of training using two modules. There are a total of over 900 000 ASHAs per link workers in the country, out of which, only 14% have completed the fourth round of training. The pace of uptake of the HBNC program has been slow. Of the annual rural birth cohort of over 17 million, about 4 million newborns have been visited by ASHA during the financial year 2013–2014 and out of this 120 000 neonates have been identified as sick and referred to health facilities for higher level of neonatal care. Supportive supervision remains a challenge, the role of ANMs in supervision needs more clarity and there are issues surrounding quality of training and the supply of HBNC kits. The program has low visibility in many states. Now is the time to tap the missed opportunity of miniscule coverage of HBNC; that at least half of the country’s birth cohort should be covered by this program by 2016, coupled with rapid scale up of the community-based treatment of neonates with pneumonia or sepsis, where referral is not possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

What are community- based interventions?

Community-based interventions are those interventions that can be delivered by a community health worker in close proximity to one’s home, including services delivered at home or to the family and through outreach sessions.1 There are several documented interventions to reduce mortality caused by sepsis, asphyxia and preterm birth complications.2 Packaging of interventions is a cost-effective and practical way of delivering them at scale.3

Community-based interventions broadly consist of two approaches: delivery of packages through home visits, and community mobilization.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Several studies have demonstrated the effect of home visits and community mobilization in isolation and also in combination. The population-level effect or impact, however, depends on the baseline neonatal mortality rate (NMR), the effect of the intervention and the population coverage of the interventions.10, 11 The effect of community-based interventions declines as the baseline NMR decreases, especially when it falls below 50.11

Global evidence on community-based newborn care

A meta-analysis of all community-based interventions till 2010 demonstrated a reduction in NMR (risk ratio (RR):0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.68–0.84), stillbirths (RR:0.84; 0.74–0.97) and perinatal mortality (RR:0.80; 0.71–0.91). It also showed an increase in referrals to health facility for pregnancy-related complications (RR:1.40; 1.19–1.65) and improved rates of early breastfeeding (RR:1.94; 1.56–2.42). The results were significant when impact was estimated for early neonatal mortality (RR: 0.74;0.64–0.86).3 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of intervention studies (with home visits as the key intervention) gives a pooled relative risk of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.44–0.87). Higher coverage (⩾50%) was associated with better survival (RR: 0.54; 0.42–0.70) than lower coverage (RR: 1.06; 0.81–1.38). Pooled data showed a reduced risk of stillbirths (RR: 0.76; 0.65–0.89).10 Yet another review suggests that home visits have maximal impact when the first visit is within the first 48 h after delivery.11

It is well-documented that higher reductions in NMR are achieved in the proof-of-principle studies; the meta-analysis estimate showed a 45% reduction (95% CI, 37–52). However, the results of the trials in south Asia in programmatic settings showed substantially lower reductions. The summary estimate represents an overall reduction in NMR of 12% (95% CI, 5–18).9

Community mobilization is also recognized as an effective strategy to improve newborn health. A meta-analysis of seven trials on community mobilization through women’s groups showed that the intervention was associated with a 37% reduction in maternal mortality (odds ratio 0.63, 95% CI, 0.32–0.94), a 23% reduction in neonatal mortality (0.77, 0.65–0.90) and a 9% non-significant reduction in stillbirths (odds ratio 0.91, 0.79–1.03). The analysis concluded that with the participation of at least a third of pregnant women and adequate population coverage, women’s groups practicing participatory learning and action are a cost-effective strategy to improve maternal and neonatal survival in low-resource settings.17

Evidence on community-based newborn care from India

Evidence on the effectiveness of home visits for improving newborn survival comes from some early studies: Pune,8 Ambala7 and Dahanu6 during 1980s and early 1990s. This was followed by ground breaking research on home-based newborn care (HBNC) in Gadchiroli between 1993 and 1998.18 This was the first field trial of HBNC that was evaluated using a quasi-experimental design in 39 intervention and 47 control villages. Village health workers trained in neonatal care made home visits and managed birth asphyxia, premature birth or low birth weight, hypothermia and breastfeeding problems. The package included preventive care along with identification of danger signs, and administration of injectable antibiotics (gentamicin) to infants with suspected sepsis.19

The study demonstrated a significant decline in mortality in neonates (by 62%), and infants (by 46%) and perinatal mortality rate (71%) by the third year.19 The decline was attributed primarily to a significant reduction in neonatal sepsis (by 76%) and birth asphyxia (by 47.6%). The scalability of the model was tested through ANKUR project in several parts of Maharashtra state by different NGOs where a 51% decline in NMR was observed.20 Since then, HBNC has been accepted as a feasible option to address neonatal deaths in underserved areas. This model has taken the shape of HBNC program, the key community-based program to deliver newborn care services in the country.

Home visits were also a part of the Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI) program that was initiated in 2004 in the country. Its effectiveness was demonstrated in a cluster randomized trial where NMR beyond 24 h was significantly lower in the clusters where IMNCI was implemented as compared with the controls (adjusted hazard ratio 0.86; 0.79–0.95). Though the effect of the intervention was seen only among home births, the intervention led to a reduction of post NMR among home births (adjusted hazard ratio 0.73; 0.63–0.84) and health-care facility births (0.81; 0.69–0.96).21

A large-scale community-based Integrated Nutrition and Health Program for behavioral change was implemented through the health system from 2001–2006. Initial evaluation revealed that the frequency of home visits improved during antenatal (16–56%) and post-natal periods (3–39%). That, however, did not translate into a reduction in NMR owing to limited coverage.4

Evidence on efficacy of community mobilization for an improvement in newborn survival was generated in the past decade. Behavior change management by community health workers resulted in a significant decline in NMR (RR 0.59; 0.47–0.74).22, 23 Improvements in birth preparedness, hygienic delivery, thermal care and breastfeeding were observed and a significant reduction in NMR was demonstrated in the intervention arm (RR=0.46; 0.35–0.60).23

Another trial evaluated the effect of participatory interventions through women’s groups.24 The intervention involved local female facilitators guiding women’s groups through a cycle of meetings and activities through participatory learning and action. During such meetings, women identified, prioritized, and analyzed local maternal and neonatal health problems and subsequently devised and implemented strategies to address them. This trial, conducted in the tribal districts of Jharkhand and Odisha, showed a significant decline in NMR by 32% (OR 0.68; 0.59–0.78) over a period of 3 years (2005-2008).24, 25 The effect size was greater (59%) among the most marginalized as compared with less marginalized (35%) populations. The impact was sustained beyond the intervention period.26

Community-based programs in India

The existing evidence-based interventions have been packaged into two programs: IMNCI and HBNC.

Integrated management of newborn and childhood illnesses–IMNCI

During the mid-1990s, the World Health Organization in collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund and many other agencies, institutions and individuals, developed a strategy known as Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. This strategy has been adapted for India as IMNCI adding N for newborn baby as neonatal deaths constitute a major proportion of childhood deaths. The program is based on the principle that impact on newborn health is greatest when community and clinical care are linked and has a strong health system strengthening component.14

IMNCI was rolled out in 2004 across the country and a rapid expansion was observed.27, 28 Home visits of newborn and standardized case management of newborns and children through community workers (female health workers and Anganwari workers) were the key components. Impact of IMNCI was assessed from the district level data of two time periods: 2002–2004 and 2007–2008 from 12 districts across 7 states. The coverage of home visits in IMNCI districts reached only 64% of target neonates. The number of workers trained per year per district ranged from 208 to 1285 across 223 districts in different states.28 Out of the total 202 015 workers trained between 2004 and 2008 in IMNCI, 56% were Anganwari workers (frontline workers under Integrated Child development Services in India), 14% ASHAs and 15% Auxiliary Nursing Midwives (ANMs) or female health workers.28

Since 2012, there has been a shift in the implementation of IMNCI. Currently, only the ANMs are responsible for implementing this program and the Anganwari workers have been excluded.29 The program is now operational in 505 districts in 27 states and 4 union territories.30

Home-based newborn care

The Government of India launched the HBNC program in 2011 with the purpose of improving community newborn care practices, early detection of neonatal illnesses and appropriate referral through home visits. The services are supposed to be delivered by the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), the frontline workers at the village level responsible to deliver preventive care services for mothers and newborns in the community.31

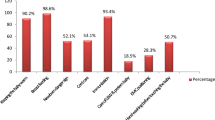

Currently, there are a total of 904 195 ASHAs per link workers in the country.30 A structured course comprised of seven modules has been developed for their training, out of which Modules 6 and 7 focus on newborn care. These modules are covered in four rounds of training over a period of 1 year.32 Recent data shows that 78.2% ASHAs have completed round 1 training, 65.7% have completed round 2 training, whereas only 14% have completed round 4 training (see Figure 1).30, 33 As per the available data, about 4 million newborns have been visited by ASHAs during the financial year 2013–2014 and out of this 120 000 neonates have been identified as sick and referred to health facilities for further care.30

Status of training of ASHAs on Home-Based Newborn Care (Modules 6 &7). Adapted with permission from All India Executive Summary-Status as on 31 March 2016. National Rural Health Mission Report. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi (http://www.nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/mis-report/March-2016/1-NRHM.pdf), copyright 2016 Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

To accelerate the uptake of the HBNC program in states with high NMR—Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar and Odisha, the model has been adapted by Norweignian India Partnership Initiative.34 Several innovative approaches were adopted; it improvised on the pedagogy techniques to train ASHAs, introduced a supportive supervision mechanism, introduced another cadre of worker—Yashoda—to provide care and counseling services to the mothers and newborns and function as a birth companion in maternity wards.35 The analysis done to assess the incremental and combined benefits of Yashoda and ASHA on newborn care showed that the dual exposure of mothers to both Yashoda and Norweignian India Partnership Initiative trained ASHA had an significant incremental effect (almost 3 times) on newborn care indicators related to both counseling and practice (OR varying between 2.96–4.98, P<0.001).36

Strengthening Implementation of community-based programs

The commitment of the government to reach out to its most vulnerable and poorest citizens is reflected in the investment that has gone into the expansion of community-based programs. There is a large pool of trained people in each community to deliver these services which include the ANMs, ASHAs and the Anganwari workers; however, there is a need to structurally link these workers and define their roles. An urgent requirement is to integrate the HBNC and the IMNCI programs to build a comprehensive community-based newborn care.

There is emerging evidence that ASHAs in all the states had received training and were having all three of their primary roles: improving health awareness in the community, providing basic curative care and facilitation of access to services from the health system.37 Despite this, the execution of the programs is fraught with several challenges, as detailed in several assessments.37, 38, 39, 40, 41

Supply side challenges and opportunities

The systemic factors that are impediment to the implementation of community-based programs are related to lack of skilled personnel, issues pertaining to logistics, and weak supervision and monitoring systems. The states have evolved some innovative ways to address the challenges.

Capacity of health-care functionaries

Good-quality training is critical to the functionality of frontline workers. Capacity building occurs not only during induction but is a continuous process. ASHAs have been described as vibrant and enthusiastic, and they take pride in delivering community-based services.40 However, some initial assessments have revealed that they lacked clarity in defining their job responsibilities.42 This could be attributed either to the quality of personnel chosen as ASHAs (as selection criteria were not followed in some places) or inadequate training after their recruitment.42, 43 Besides having the training for a duration that was less than recommended, the pace and quality of training were also serious concerns. In most states, the minimum level of training was achieved, but the pace of training fell far short of what was required.39, 40 Competency-based training did not figure in the design of the training modules.39 This might have influenced them to work more for promoting institutional deliveries and counseling for women on all aspects of pregnancy.37 Service provision under HBNC was largely limited to health education and referral.41 Low levels of effectiveness were observed in terms of providing newborn care services.37

Quality of training gets compromised as program implementation expands. Besides adhering to the stipulated duration of training, the quality of trainers should also be ensured.39 The quality can presumably be improved by using information technology, or using teaching aids that are more interactive and engaging. There is a need to have refresher courses. Pictorial job aids and frequent refresher trainings are crucial to ensure that the ASHA retain her skills.36, 42 The monthly meetings at primary health centers can be utilized effectively for continuing education and refresher courses.

Logistics issues

Disbursement of incentives and allowances were operational issues highlighted in different reports. Evidence shows that the efficiency with which the incentives reached the ASHAs was a concern.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 and 42 Some states, however, reported to have developed robust mechanisms of accounting and timely payment.39

Drug kits that are essential to service provision were either supplied late or not replenished nor maintained as reported in initial assessments.33, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Ad hoc measures used for refilling of ASHA drug kits led to frequent shortages in several states.40 The quality of HBNC kits was also not uniform across states.33

Many states also provide non-monetary incentives. For instance, Assam has introduced a medical insurance scheme for ASHAs, whereas Chhattisgarh has a more elaborate welfare program.40 Reports of grievances being addressed through an informal process during monthly meetings were shared from states like Odisha, Tripura and Uttar Pradesh. Rajasthan has also started a helpline for complaints related to payment but awareness about the helpline was low among ASHAs.40

Supervision and monitoring

Supportive supervision is the cornerstone of any community-based program—and has been identified as a weak area in IMNCI and HBNC programs.28, 41, 43 Assessments show that a formal structure for supervision of ASHAs is lacking. At the ground level, it is unclear whether the ANM or the ASHA facilitator is the key supervisor for HBNC.

Data indicate that out of all the districts where IMNCI is being implemented, only one-third had reported about supervision. The proportion of supervisors trained varied from 0% to around 70%.28 In practice, there exists no formal system for supervision at any level; either in the form of supervisory checklist or regularly monitoring the filled neonatal forms or monthly review at the block or district level. HBNC-related data is not part of the Health Management Information System of the district, moreover this is not discussed during monthly review meetings.41

Various methods to improve supportive supervision have been proposed. Peer supervision by one of the trained frontline workers and health workers could be a strategy.28 Restructuring ASHA monthly meetings to discuss their skills and knowledge could be another potential strategy.44 Besides, engaging NGOs for monitoring community-based programs would also help.45

Demand side challenges and opportunities

Low demand for services and delayed care seeking are linked with barriers of low acceptability, affordability and quality of care. These factors are being addressed by the recent initiatives launched by the Government through various programs.

Care-seeking behavior

The general reasons behind poor utilization of care services for newborns are poor recognition of illness, sociocultural traditions of newborn seclusion, distance to facility or provider, poor quality of care at facilities, lack of financial resources to access care or transport, opportunity costs of missed work or child care. People mostly prefer non-government sources for seeking care.46 The Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram aims to overcome some of these logistic and financial barriers to care seeking.47

The gender of the child influences care seeking to a very large extent and is significantly associated with perception of neonatal illnesses.46 For instance in UP, recognition of the first illness was on the 11th day where the newborn was female, whereas it was on the 9th day for males. In a study, overall rate of perceived illness was lower for females (56 versus 68% for boys). Reports from UP and Maharashtra suggest that households prefer expensive private facilities for treatment of male neonates and free government facilities for females (65 versus 43%).46, 48

Care seeking can be improved by achieving high coverage of home-based care and utilizing those opportunities to educate families to recognize signs of illness early. The Village Health and Nutrition Days platform can be utilized to impart health education and raising community awareness on entitlements given through government programs. The issue of gender sensitization should be highlighted at all levels.49

Opportunities to treat sick neonates

In addition to addressing barriers to accessing facility-based care, another approach is to take effective treatment close to the families. A large body of research has demonstrated that: (a) community health workers can identify neonates and infants with possible sepsis, and (b) a large proportion of neonates with sepsis (who are not critically sick and do not require oxygen or IV fluids and so on) can be treated safely on an ambulatory basis with one oral antibiotic and intramuscular gentamicin when families cannot accept or do not have access to the standard-of-care hospital-based treatment.18, 20, 50

After careful scrutiny of evidence and program imperatives, the Government of India has developed operational guidelines on the use of intramuscular gentamicin by ANMs for management of sepsis in young infants (under 2 months of age) where referral is not possible or is refused. If an infant is identified to have possible serious infection by the IMNCI algorithm, and referral advice is not followed, ANM would offer to treat the infant with a combination of injectable gentamicin plus oral amoxicillin for a period of 7 days.50 It is expected that this approach would reduce deaths due to sepsis and pneumonia particularly among the underserved infants.

Another approach is to engage the private sector in treating sick neonates through a voucher, insurance or any other financing mechanism. The public health program thrust should remain to use the provisions of Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram liberally to connect sick neonates to the facilities. It is equally important that facilities (community health centers, district hospitals and medical college & hospitals, and so on) have well-functioning newborn care services.

Conclusion

The main supply and demand side factors need to be addressed and strategies implemented to increase coverage of neonatal health interventions within the health-care system. An impact will be observed only when the coverage of neonatal health-care packages in the community improves; especially in areas where NMR is high. As NMR improves, equal attention needs to be given to facility-level care and services. India has invested a lot of resources in developing and implementing home- and community-based newborn care. It is important to consolidate the efforts made so far, find innovative solutions to address the challenges, have concerted action points and evolve as we go along.

Recommendations on community- and home-based newborn care

-

Improve the coverage and quality of the HBNC program by:

-

○ Improving the pace and quality of training,

-

○ Operationalizing an effective supportive supervisory mechanism with role clarity of ANMs and ASHA supervisors,

-

○ Ensuring uninterrupted supply of ASHA kits and replenishment thereof,

-

○ Timely reimbursement of ASHA incentives,

-

○ Improving the reporting system.

-

-

Move rapidly from the training phase of HBNC into full operationalization; aim to cover at least 50% of the annual newborn cohort in the country under HBNC by 2016 and 80% by 2017.

-

Continue to train, engage and monitor Anganwari workers in IMNCI.

-

Ensure that all female health workers (ANMs) are trained in IMNCI.

-

Scale up new operational guidelines allowing ANMs to treat neonates with suspected sepsis, where referral is not possible or refused, using injectable gentamicin and oral amoxicillin.

-

Deepen the community participation processes for maternal, newborn and child health by involving the women’s groups more systematically.

-

Increase coverage of Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram to overcome logistic and financial barriers to treatment of sick neonates and connect poor families to facilities.

-

Invest in operations research to refine HBNC and IMNCI for more effective, efficient, and equitable implementation of community-based newborn health programs.

References

Nair N, Tripathy P, Prost A, Costello A, Osrin D . Improving newborn survival in low-income countries: community-based approaches and lessons from South Asia. PLoS Med 2010; 7 (4): e1000246.

Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA . Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics 2005; 115 (Supplement 2): 519–617.

Lassi ZS, Haider BA, Bhutta ZA . Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 10 (11): CD007754.

Baqui A, Williams EK, Rosecrans AM, Agrawal PK, Ahmed S, Darmstadt GL et al. Impact of an integrated nutrition and health programme on neonatal mortality in rural northern India. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86 (10): 796–804A.

WHO, UNICEF. Home visits for the newborn child: a strategy to improve survival – WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. Available at: www.unicef.org/spanish/health/files/WHO_FCH_CAH_09.02_eng.pdf (Accessed on 15 August 2016).

Daga S, Daga A, Dighole R, Patil R, Dhinde H . Rural neonatal care: Dahanu experience. Indian Pediatr 1992; 29 (2): 189–193.

Datta N, Kumar V, Kumar L, Singhi S . Application of case management to the control of acute respiratory infections in low-birth-weight infants: a feasibility study. Bull World Health Organ 1987; 65 (1): 77.

Pratinidhi A, Shah U, Shrotri A, Bodhani N . Risk-approach strategy in neonatal care. Bull World Health Organ 1986; 64 (2): 291.

Kirkwood BR, Manu A, ten Asbroek AH, Soremekun S, Weobong B, Gyan T et al. Effect of the Newhints home-visits intervention on neonatal mortality rate and care practices in Ghana: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381 (9884): 2184–2192.

Gogia S, Sachdev HS . Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88 (9): 658–666.

Gogia S, Ramji S, Gupta P, Gera T, Shah D, Mathew JL et al. Community based newborn care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence: UNICEF-PHFI series on newborn and child health, India. Indian Pediatr 2011; 48 (7): 537–546.

Claeson M, Waldman RJ . The evolution of child health programmes in developing countries: from targeting diseases to targeting people. Bull World Health Organ 2000; 78 (10): 1234–1245.

Bhutta ZA, Ali S, Cousens S, Ali TM, Haider BA, Rizvi A et al. Interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival: what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make? Lancet 2008; 372 (9642): 972–989.

Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, Begkoyian G, Fogstad H, Walelign N et al. Systematic scaling up of neonatal care in countries. Lancet 2005; 365 (9464): 1087–1098.

Martines J, Paul VK, Bhutta ZA, Koblinsky M, Soucat A, Walker N et al. Neonatal survival: a call for action. Lancet 2005; 365 (9465): 1189–1197.

Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L et al. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 2005; 365 (9463): 977–988.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A et al. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 381 (9879): 1736–1746.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD . Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999; 354 (9194): 1955–1961.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB . Reduced incidence of neonatal morbidities: effect of home-based neonatal care in rural Gadchiroli, India. J Perinatol 2005; 25: S51–S61.

Mavalankar DV, Raman P . ANKUR Project. A case study of replication of Home Based Newborn Care. Centre for Management Health Services. Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India.

Bhandari N, Mazumder S, Taneja S, Sommerfelt H, Strand TA . Effect of implementation of Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) programme on neonatal and infant mortality: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012; 344: e1634.

Kumar V, Kumar A, Darmstadt GL . Behavior change for newborn survival in resource-poor community settings: bridging the gap between evidence and impact Seminars in Perinatology Vol 34; 2010; 446–461.

Kumar V, Mohanty S, Kumar A, Misra RP, Santosham M, Awasthi S et al. Effect of community-based behaviour change management on neonatal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 372 (9644): 1151–1162.

Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, Mahapatra R, Borghi J, Rath S et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010; 375 (9721): 1182–1192.

Houweling TA, Tripathy P, Nair N, Rath S, Rath S, Gope R et al. The equity impact of participatory women’s groups to reduce neonatal mortality in India: secondary analysis of a cluster-randomised trial. Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42 (2): 520–532.

Roy SS, Mahapatra R, Rath S, Bajpai A, Singh V, Rath S et al. Improved neonatal survival after participatory learning and action with women's groups: a prospective study in rural eastern India. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91 (6): 426–433B.

Kumar R . IMNCI Factsheet for 14 states—INDIA. PGIMER: Chandigarh, India, 2011.

Mohan P, Kishore B, Singh S, Bahl R, Puri A, Kumar R et al. Assessment of implementation of integrated management of neonatal and childhood illness in India. J Health Popul Nutr 2011; 29 (6): 629.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Annual Report 2013–2014. Available at http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/media/publication/Annual_Report-Mohfw.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2015).

Division of Child Health and Immunization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. New Delhi. Monthly programme monitoring sheets.; 2014.

Revised Home Based Newborn Care Operational guidelines, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. New Delhi. 2014. Available at: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/child-health/guidelines/Revised_Home_Based_New_Born_Care_Operational_Guidelines_2014.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2016).

ASHA status of selection and training. Available at http://nrhm.gov.in/communitisation/asha/about-asha.html (accessed on 19 January 2015).

Seventh Common Review Mission. Government of India. New Delhi National Rural Health Mission 2013.

Pappu K, Kumar H, NPradhan, Misra A, Brusletto K . Experiences with implementation of a district based comprehensive newborn care package. J Neonatol 2011; 25: 2.

Home based newborn care plus. Available at http://www.nipi.org.in/DisplayMoreNew.aspx?itemid=2316 (accessed on 20 January 2015).

Public Health Foundation of India. Assessing and Supporting NIPI Interventions— A Technical Report. New Delhi. 2011.

Mony P, Raju M. Evaluation of ASHA programme in Karnataka under the National Rural Health Mission. BMC Proceedings 2012 6(Suppl 5):P12. doi:10.1186/1753-6561-6-S5-P12.

Planning Commission, Government of India. Evaluation Study of National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) In 7 States, February 2011.

ASHA. Which way forward? Evaluation of ASHA programme. National Health Services resource Centre. New Delhi. 2011.

Sixth Common Review Mission. National Rural Health Mission. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India, New Delhi. 2012.

Nakkeeran N, Patel R, Shetty Y, Kumbar B . Scale-up of SEARCH’s home based newborn care in Karnataka—a case study. Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar and save the Children: Gandhinagar, India, 2014.

Bajpai N, Dholakia JDS Improving access, service delivery and efficiency of the public health system in rural India. Mid term evaluation of the National Rural Health Mission. CGSD working paper no. 37 2009. Available at: http://globalcenters.columbia.edu/mumbai/files/globalcenters_mumbai/F.%20FINAL_NRHM_Report%202009.pdf. (accessed on 18 August 2015).

Bajpai N, Dholakia R . Improving the performance of Accredited Social Health Activists in India. Working paper no. 1. 2011. Available at: http://globalcenters.columbia.edu/files/cgc/pictures/Improving_the_Performance_of_ASHAs_in_India_CGCSA_Working_Paper_1.pdf. (accessed on 18 August 2015).

Strengthening ASHA support mechanisms for improved newborn care in Uttar Pradesh. Available at http://www.intrahealth.org/page/strengthening-asha-support-mechanisms-for-improved-newborn-care-in-uttar-pradesh-technical-brief (accessed on 5 January 2015).

Self Employed Women’s Association. Available at http://www.sewa.org/ (accessed on 31 Aug 2013).

Willis JR, Kumar V, Mohanty S, Singh P, Singh V, Baqui AH et al. Gender differences in perception and care-seeking for illness of newborns in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J Health Popul Nutr 2009; 27 (1): 62.

National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. Guidelines for Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram. 2011. Available at:http://nrhm.gov.in/janani-shishu-suraksha-karyakram.html. (accessed on15th July 2015).

Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS . Awareness and health care seeking for newborn danger signs among mothers in peri-urban Wardha. Indian J Pediatr 2009; 76 (7): 691–693.

Village Health Nutrition Day. Available at nrhm.gov.in/communitisation/village-health-nutrition-day.html (accessed on 19 January 2015).

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. Use of gentamicin by ANMs for management of sepsis in young infants under specific situations. Operational Guidelines. 2014. Available at: http://www.newbornwhocc.org/SOIN_PRINTED%2014-9-2014.pdf. (accessed on 20 December 2015).

Acknowledgements

Support for this publication was provided by Save the Children’s Saving Newborn Lives program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Neogi, S., Sharma, J., Chauhan, M. et al. Care of newborn in the community and at home. J Perinatol 36 (Suppl 3), S13–S17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.185

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.185

This article is cited by

-

Utilization of Postnatal Healthcare Services Delivered through Home Visitation and Health Facilities for Mothers and Newborns: An Integrative Review from Developing Countries

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2020)

-

Distinct mortality patterns at 0–2 days versus the remaining neonatal period: results from population-based assessment in the Indian state of Bihar

BMC Medicine (2019)

-

Effectiveness of a Quality Improvement Program Using Difference-in-Difference Analysis for Home Based Newborn Care – Results of a Community Intervention Trial

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2019)

-

Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) Strategy and its Implementation in Real Life Situation

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2019)

-

Cost analysis of implementing mHealth intervention for maternal, newborn & child health care through community health workers: assessment of ReMIND program in Uttar Pradesh, India

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2018)