Abstract

This article summarizes the historical background for the use of oxygen during newborn resuscitation and describes some of the research and the process of changing the previous practice from a high- to a low-oxygen approach. Findings of a recent Cochrane review suggest that more than 100 000 newborn lives might be saved globally each year by changing from 100 to 21% oxygen for newborn resuscitation. This estimate represents one of the largest yields for a simple therapeutic approach to decrease neonatal mortality in the history of pediatric research. Available data also suggest that, for the very low birth weight infant, use of the low-oxygen approach should be considered with the understanding that some of the smallest and sickest preterm neonates will need some level of oxygen supplementation during the first minutes of postnatal life. As more data are needed for the very preterm population, creation of strict guidelines for these infants would be premature at present. However, it can be stated that term and late preterm infants in need of resuscitation should, in general, be started on 21% oxygen, and if resuscitation is not started with 21% oxygen, a blender should be available, enabling the administration of the lowest FiO2 possible to keep heart rate and SaO2 within the target range. For extremely low birth weight infants, initial FiO2 could be between 0.21 and 0.30 and adjusted according to the response in SaO2 and heart rate.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Obladen M . History of neonatal resuscitation. Part 2: oxygen and other drugs. Neonatology 2009; 95: 91–96.

Klaus M, Meyer BP . Oxygen therapy for the newborn. Pediatr Clin North Am 1966; 13: 731–752.

Emergency Cardiac Care Committee Subcommittees of the American Heart Association. Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care, IV: pediatric basic life support. J Am Med Assoc 1992; 268: 2276–2281.

Campbell AGM, Cross KW, Dawes GS, Hyman AI . A comparison of air and O2 in a hyperbaric chamber by positive pressure ventilation, in the resuscitation of newborn rabbits. J Pediatr 1966; 68: 153–163.

Saugstad OD, Aasen AO . Plasma hypoxanthine concentrations in pigs. A prognostic aid in hypoxia. Eur Surg Res 1980; 12: 123–129.

Granger DN, Rutili G, McCord JM . Superoxide radicals in feline intestinal ischemia. Gastroenterology 1981; 81: 22–29.

Perez-de-Sa V, Cunha-Goncalves D, Nordh A, Hansson S, Larsson A, Ley D et al. High brain tissue oxygen tension during ventilation with 100% oxygen after fetal asphyxia in newborn sheep. Pediatr Res 2009; 65: 57–61.

Saugstad OD . Hypoxanthine as an indicator of hypoxia: its role in health and disease through free radical production. Pediatr Res 1988; 23: 143–150.

Poulsen JP, Oyasaeter S, Saugstad OD . Hypoxanthine, xanthine, and uric acid in newborn pigs during hypoxemia followed by resuscitation with room air or 100% oxygen. Crit Care Med 1993; 21: 1058–1065.

Rootwelt T, Løberg EM, Moen A, Oyasaeter S, Saugstad OD . Hypoxemia and reoxygenation with 21 or 100% oxygen in newborn pigs: changes in blood pressure, base deficit, and hypoxanthine and brain morphology. Pediatr Res 1992; 32: 107–113.

Rootwelt T, Odden JP, Hall C, Ganes T, Saugstad OD . Cerebral blood flow and evoked potentials during reoxygenation with 21 or 100% O2 in newborn pigs. J Appl Physiol 1993; 75: 2054–2060.

Feet BA, Medbö S, Rootwelt T, Ganes T, Saugstad OD . Hypoxemic resuscitation in newborn piglets: recovery of somatosensory evoked potentials, hypoxanthine, and acid-base balance. Pediatr Res 1998; 43: 690–696.

Feet BA, Yu XQ, Rootwelt T, Oyasaeter S, Saugstad OD . Effects of hypoxemia and reoxygenation with 21 or 100% oxygen in newborn piglets: extracellular hypoxanthine in cerebral cortex and femoral muscle. Crit Care Med 1997; 25: 1384–1391.

Kutzsche S, Ilves P, Kirkeby OJ, Saugstad OD . Hydrogen peroxide production in leukocytes during cerebral hypoxia and reoxygenation with 100 or 21% oxygen in newborn piglets. Pediatr Res 2001; 49: 834–842.

Kutzsche S, Kirkeby OJ, Rise IR, Saugstad OD . Effects of hypoxia and reoxygenation with 21 and 100%-oxygen on cerebral nitric oxide concentration and microcirculation in newborn piglets. Biol Neonate 1999; 76: 153–167.

Medbø S, Yu XQ, Asberg A, Saugstad OD . Pulmonary hemodynamics and plasma endothelin-1 during hypoxemia and reoxygenation with room air or 100% oxygen in a piglet model. Pediatr Res 1998; 44: 843–849.

Ramji S, Ahuja S, Thirupuram S, Rootwelt T, Rooth G, Saugstad OD . Resuscitation of asphyxic newborn infants with room air or 100% oxygen. Pediatr Res 1993; 34: 809–812.

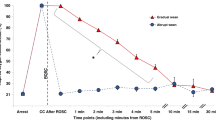

Saugstad OD, Rootwelt T, Aalen O . Resuscitation of asphyxiated newborn infants with room air or oxygen: an international controlled trial: the Resair 2 study. Pediatrics 1998; 102: e1.

Saugstad OD, Ramji S, Irani SF, El-Meneza S, Hernandez EA, Vento M et al. Resuscitation of newborn infants with 21 or 100% oxygen: follow-up at 18 to 24 months. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 296–300.

Munkeby BH, Børke WB, Bjørnland K, Sikkeland LI, Borge GI, Halvorsen B et al. Resuscitation with 100% O2 increases cerebral injury in hypoxemic piglets. Pediatr Res 2004; 56: 783–790.

Solberg R, Andresen JH, Pettersen S, Wright MS, Munkeby BH, Charrat E et al. Resuscitation of hypoxic newborn piglets with supplementary oxygen induces dose-dependent increase in matrix metalloproteinase-activity and down-regulates vital genes. Pediatr Res 2010; 67 (3): 250–256.

Lakshminrusimha S, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH, Swartz DD, Ryan RM, Gugino SF et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in neonatal lambs resuscitated with 21, 50, and 100% oxygen. Pediatr Res 2007; 62: 313–318.

Lakshminrusimha S, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH, Ryan RM, Gugino SF, Morin 3rd FC et al. Pulmonary arterial contractility in neonatal lambs increases with 100% oxygen resuscitation. Pediatr Res 2006; 59: 137–141.

Markus T, Hansson S, Amer-Wåhlin I, Hellström-Westas L, Saugstad OD, Ley D . Cerebral inflammatory response after fetal asphyxia and hyperoxic resuscitation in newborn sheep. Pediatr Res 2007; 62: 71–77.

Koch JD, Miles DK, Gilley JA, Yang CP, Kernie SG . Brief exposure to hyperoxia depletes the glial progenitor pool and impairs functional recovery after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 1294–12306.

Vento M, Sastre J, Asensi MA, Viña J . Room-air resuscitation causes less damage to heart and kidney than 100% oxygen. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172: 1393–1398.

Oxer HF . Simply add oxygen: why isn’t oxygen administration taught in all resuscitation training? Resuscitation 2000; 43: 163–169.

Niermeyer S, Kattwinkel J, Van Reempts P, Nadkarni V, Phillips B, Zideman D et al. International guidelines for neonatal resuscitation: an excerpt from the guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care: international consensus on science. Contributors and reviewers for the neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics 2000; 106: e29.

WHO. Basic Newborn Resuscitation: A Practical Guide. WHO: Geneva, 1998.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation. Pediatrics 2006; 117: e978.

Saugstad OD, Ramji S, Soll RF, Vento M . Resuscitation of newborn infants with 21 or 100% oxygen: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology 2008; 94: 176–182.

Davis PG, Tan A, O’Donnell CP, Schulze A . Resuscitation of newborn infants with 100% oxygen or air: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2004; 364: 1329–1333.

Saugstad OD, Ramji S, Vento M . Resuscitation of depressed newborn infants with ambient air or pure oxygen: a meta-analysis. Biol Neonate 2005; 87: 27–34.

Rabi Y, Rabi D, Yee W . Room air resuscitation of the depressed newborn: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2007; 72: 353–363.

Linner R, Werner O, Perez-de-Sa V, Cunha-Goncalves D . Circulatory recovery is as fast with air ventilation as with 100% oxygen after asphyxia-induced cardiac arrest in piglets. Pediatr Res 2009; 66: 391–394.

Solevåg AL, Dannevig I, Nakstad B, Saugstad OD . Resuscitation of severely asphyctic newborn pigs with cardiac arrest by using 21 or 100% oxygen. Neonatology 2010; 98: 64–72.

Yeh ST, Cawley RJ, Aune SE, Angelos MG . Oxygen requirement during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to effect return of spontaneous circulation. Resuscitation 2009; 80: 951–955.

Matsiukevich D, Randis TM, Utkina-Sosunova I, Polin RA, Ten VS . The state of systemic circulation, collapsed or preserved defines the need for hyperoxic or normoxic resuscitation in neonatal mice with hypoxia-ischemia. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 224–229.

Liu JQ, Saugstad OD, Cheung PY . Using 100% oxygen for the resuscitation of term neonates until evidence of spontaneous circulation: More investigations needed. Resuscitation 2010; 81: 145–147.

Canadian Paediatric Society. Neonatal resuscitation program. http://www.cps.ca.

Australian Resuscitation Council. Airway and mask ventilation of the newborn infant. Australian Resuscitation Council February 2006, Guideline 13.4: 1–9. Available from http://www.resus.org.au/(Accessed May 2006).

van den Dungen FA, van Veenendaal MB, Mulder AL . Clinical practice: neonatal resuscitation. A Dutch consensus. Eur J Pediatr 2010; 169: 521–527.

Resuscitation Council UK. Newborn life support. http://www.resus.org.uk.

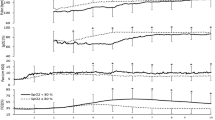

Escrig R, Arruza L, Izquierdo I, Villar G, Sáenz P, Gimeno A et al. Achievement of targeted saturation values in extremely low gestational age neonates resuscitated with low or high oxygen concentrations: a prospective, randomized trial. Pediatrics 2008; 121: 875–881.

Wang CL, Anderson C, Leone TA, Rich W, Govindaswami B, Finer NN . Resuscitation of preterm neonates by using room air or 100% oxygen. Pediatrics 2008; 121: 1083–1089.

Vento M, Moro M, Escrig R, Arruza L, Villar G, Izquierdo I et al. Preterm resuscitation with low oxygen causes less oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 2009; 124: 439–449.

Dawson JA, Kamlin CO, Wong C, te Pas AB, O’Donnell CP, Donath SM et al. Oxygen saturation and heart rate during delivery room resuscitation of infants <30 weeks’ gestation with air or 100% oxygen. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009; 94: F87–F91.

Stola A, Schulman J, Perlman J . Initiating delivery room stabilisation/resuscitation in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants with an FiO2 less than 100% is feasible. J Perinatol 2009; 29: 548–552.

Ezaki S, Suzuki K, Kurishima C, Miura M, Weilin W, Hoshi R et al. Resuscitation of preterm infants with reduced oxygen results in less oxidative stress than resuscitation with 100% oxygen. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2009; 44: 111–118.

Finer N, Saugstad O, Vento M, Barrington K, Davis P, Duara S et al. Use of oxygen for resuscitation of the extremely low birth weight infant. Pediatrics 2010; 125 (2): 389–391.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This paper resulted from the Evidence vs Experience in Neonatal Practices conference, 19 to 20 June 2009, sponsored by Dey, LP.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saugstad, O. Why are we still using oxygen to resuscitate term infants?. J Perinatol 30 (Suppl 1), S46–S50 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.94

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2010.94