Abstract

The pharmacokinetics among children has been altered dynamically. The difference between children and adults is caused by immaturity in things such as metabolic enzymes and transport proteins. The periods when these alterations happen vary from a few days to some years after birth. We hypothesized that the effect of gene polymorphisms associated with the dose of medicine could be influenced by age. In this study, we analyzed 51 patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) retrospectively. We examined the associations between the polymorphism in NUDT15 and clinical data, especially the dose of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP). Ten of the patients were heterozygous for the variant allele in NUDT15. In patients under 7 years old with NUDT15 variant allele, the average administered dose of 6-MP was lower than that for the patients homozygous for the wild-type allele (P=0.04). Genotyping of NUDT15 could be a beneficial to estimate the tolerated dose of 6-MP for patients with childhood ALL, especially at a preschool age in Japan. Furthermore, the analysis with stratification by age might be useful in pharmacogenomics among children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The different sensitivity for drugs between children and adults has been well known. The influence of growth and development on drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion is thought to be a major cause of the differences.1 Recently, some reports showed an age-dependent influence of gene polymorphisms.1, 2, 3

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a rare disease, which occurs at a rate of <500 per year in Japan, but remains the most frequent type of pediatric cancer.4 Its treatment protocol has been well developed. It achieved a >90% overall survival rate at 5 years in the 2000 s among Japanese children with ALL.5 In most treatment protocols, childhood ALL is treated based on the risk classification.6, 7 The major factors of classifying patients are age and initial white blood cell (WBC) count at diagnosis. Older age and higher WBC count at diagnosis are risk factors of poor prognosis. The key drugs to prevent disease relapse are daily oral 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and weekly methotrexate (MTX) during maintenance therapy. The dose of 6-MP was reported to have an association with diphosphate-linked moiety X-type motif 15 (NUDT15), thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) and inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPA), which are the enzymes of 6-MP metabolism.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

We hypothesized that the influence on gene polymorphisms associated with the dose of 6-MP during maintenance therapy depended on the patients’ age. In this study, we examined the association between three polymorphisms (NUDT15, TPMT and ITPA) and clinical data of childhood ALL with stratification by age in Japan.

Materials and methods

Patients and treatment

We enrolled patients treated at the University of Tsukuba Hospital or Ibaraki Children’s Hospital. All of the patients with childhood ALL underwent chemotherapy according to the Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group protocol (L-95, L-99 and L-0416) between 1998 and 2014.6, 15 All of them completed the maintenance therapy of childhood ALL. Patients were categorized according to their age (under 7 years old or 7 years old and older) and initial WBC count (under 50 000 per 10−6 l or 50 000 per 10−6l and more than 50 000 per 10−6 l) at the diagnosis as the risk classification in Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group protocol. Patients in the highest risk group who had an initial WBC count of more than 50 000 per 10−6 l and were above 10 years old, or whose initial WBC count was more than 100 000 per 10−6 l at any age or patients with congenital chromosome abnormalities such as trisomy 21 were excluded.

In these protocols, the starting dose of oral 6-MP was 40 mg m−2 daily and oral MTX was 25 mg m−2 weekly. The dose of 6-MP and MTX was adjusted by physicians according to the WBC count and hepatotoxicity within the WBC count of 2000–3500 per 10−6 l, and alanine transferase <750 IU l−1.

Data collection

Clinical data were collected from patients’ medical records retrospectively. We calculated the total amount of 6-MP and MTX for each patient and divided them by the number of days and weeks during maintenance therapy as the average dose.

We collected clinical data during 6 to 12 months from the beginning of the maintenance therapy, including WBC count, hemoglobin, platelet count and the highest alanine transferase level. Current situations such as disease status and follow-up periods were also included.

Frequency and the reason for therapy interruption during maintenance therapy were also collected. Frequent withdrawal due to infection or fever was defined as more than 4 times in a year.

Ethical statement

The protocol for this study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Tsukuba Hospital and Ibaraki Children’s Hospital following the Ethical Guidelines for Human Genome/Gene Analysis Research of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents or guardians, and informed assent was also obtained from the patients appropriate to their age and understanding ability.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from the blood when patients were in complete remission using Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit: QIAGEN, Venlo, The Netherlands) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Polymorphisms of NUDT15 (c.415C>T, p.Arg139Cys, rs116855232), TPMT (c.719A>G, p.Tyr240Cys, rs1142345) and ITPA (c.94C>A, p.Pro32Thr, rs1127354) were genotyped with TaqMan PCR Genotyping Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Automatic allele calling was performed using ABI PRISM 7900HT data collection and analysis software, version 2.2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, CA, USA).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS statistical software version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.1.1 (https://www.r-project.org/). Allele frequencies of the patients were compared with the Japanese general population16 by Fisher’s exact test. Mann–Whitney’s U-test was used to analyze associations between polymorphisms and clinical data. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze the association between polymorphisms and patients with frequent withdrawal or relapse.

Results

Patient characteristics

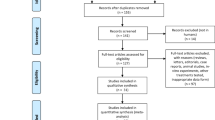

We enrolled 59 Japanese children with ALL, but eight of them were excluded because of the patients in highest risk group, congenital chromosome abnormality, and deviant protocol (Figure 1). Fifty-one Japanese children (23 males and 28 females) with ALL were analyzed. The median age at diagnosis was 5.1 (range 1.6–15.8) years old. Forty-eight patients (94.1%) were in their first complete remission and three patients (5.9%) had experienced relapse, one patient was in the second complete remission and one patient was in the third complete remission, and the other died of disease at 14 years after she had been diagnosed with leukemia. The median follow-up period from the diagnosis was 8.3 (range 1.7–17.1) years.

Genotyping of NUDT15, TPMT and ITPA

The genotyping data are summarized in Table 1. Ten patients were heterozygous for the variant allele at NUDT15 (c.415C>T, p.Arg139Cys, rs116855232), and no patient was homozygous for the variant alleles. The minor allele frequency of NUDT15 c.415C>T in the present study was 0.098, and was not significantly different from the one in the Japanese general population, which was 0.11616 (P=0.65). Allele frequency did not significantly deviate from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05) by exact test.

The minor allele frequencies of TPMT (c.719A>G, p.Tyr240Cys, rs1142345) and ITPA (c.94C>A, p.Pro32Thr, rs1127354) in the present study were not different from the Japanese general population (Table 1) and did not significantly deviate from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05) by exact test.

Association between NUDT15 genotype and clinical data

The association between the polymorphism of NUDT15 c.415C>T and clinical data is summarized in Table 2. No patients received blood transfusion because of anemia or thrombocytopenia during whole period of maintenance therapy. The average dose of 6-MP for patients with the variant allele was 27.2 mg m−2 per day and the average dose for patients with homozygote for the wild-type allele was 32.0 mg m−2 per day, which was not statistically different (P=0.27). Also, NUDT15 c.415C>T was not associated with the dose of MTX, hematological toxicity or hepatotoxicity. Considering relapse rate, one patient with heterozygote for the variant allele and two patients with homozygote for the wild-type allele had relapsed. There was no association between NUDT15 c.415C>T and relapse rate of childhood ALL in the present study (P=0.54).

Among the younger age group (under 7 years old), there were 7 patients with heterozygote for the variant allele at NUDT15 c.415C>T and 24 patients with homozygote for the wild-type allele. In the analysis of the younger age group, the average dose of 6-MP in patients with heterozygote for the variant allele at NUDT15 was 22.3 mg m−2 per day and with homozygote for the wild-type allele was 32.7 mg m−2 per day (P=0.04, Figure 2a). Among the older age group (above 7 years old or older), there were three patients with heterozygote for the variant allele and 17 patients with homozygote for the wild-type allele. The average dose of 6-MP was 37.9 mg m−2 per day in patients with heterozygote for the variant allele and 28.8 mg m−2 per day in patients with homozygote for the wild-type allele (P=0.42, Figure 2b). Polymorphism of NUDT15 had no association with the average dose of MTX, hematological toxicity and hepatotoxicity in each age group (Table 2).

Among the lower WBC count group (under 50 000/10−6 l), 10 patients were heterozygous for the variant allele at NUDT15 c.415C>T and 36 patients were homozygous for wild-type allele. There were no association between the dose of 6-MP and NUDT15 variant (P=0.16). Among the higher WBC count group (50 000 per 10−6 l and more than 50 000 per 10−6 l), all of five patients were homozygous for wild-type allele.

Association between TPMT and ITPA genotype and clinical data

Because only two patients had TPMT variant allele (c.719A>G, p.Tyr240Cys, rs1142345), the association between TPMT c.719A>G and clinical data could not be evaluated in our study. The polymorphism at ITPA (c.94C>A, p.Pro32Thr, rs1127354) had no association with the dose of 6-MP, MTX, the WBC count and hepatotoxicity (P-value is 0.59, 0.79, 0.76 and 0.82, respectively).

Discussion

The polymorphism of NUDT15 (c.415C>T, p.Arg139Cys, rs116855232) was associated with the dose of 6-MP in maintenance therapy of childhood ALL in the younger age group (under 7 years old) in the present study. In previous reports, the associations between NUDT15 variant allele and thiopurine intolerance were shown in patients among the Asian adults with inflammatory bowel disease and children with ALL, same as our result12, 17, 18, 19 And also, our results suggested that patients’ age was one of the key factors to predict thiopurine intolerance for patients with NUDT15 variant.

The role of NUDT15 is thought to have an anti-mutagenic activity.20, 21 NUDT15 hydrolyzes 8-oxo-dGTP and 8-oxo-dGDP which induced base mispairing such as AT-to-CG and GC-to-TA in cells. The loss of function of NUDT15 may let 8-oxo-dGTP and 8-oxo-dGDP stay at high levels in cells. As a result, base mispairing occurs frequently and induces cells to apoptosis. Meanwhile, 6-MP is metabolized by enzymes and inhibits DNA synthesis. Thus, production of WBC is suppressed at bone marrow. We assumed that suppressed production of WBC due to NUDT15 variant became obvious while using 6-MP for a long period. Recently, Moriyama et al.14 newly reported that NUDT15 inactivated thiopurine metabolites and was directly related to their cytotoxic effects by using NUDT15-knockdown human lymphoid cells. We supposed that NUDT15 had an age-dependency as CYPs or the younger patients are politically powerless that they are susceptible to gene polymorphisms.

With that the minor allele frequency of NUDT15 c.415C>T among Japanese is 0.11616, we estimate that more than 10% of patients carries variant allele at NUDT15 c.415C>T who could develop severe leukopenia due to 6-MP. Considering the higher minor allele frequency among Japanese more than Caucasians (0.116 and 0.002, respectively), this polymorphisms could explain the stronger effect on bone marrow toxicity among Japanese than Caucasians. Genotyping of NUDT15 before using 6-MP could be a valuable clinical examination to predict the appropriate dose of 6-MP especially for the Japanese younger population.

In this study, the minor allele frequency of TPMT was as low as that shown in previous reports.12, 22 Even though the dose of 6-MP in patients with TPMT variant allele was lower than in those with homozygote for the wild-type allele, genotyping of TPMT would not significantly influence 6-MP tolerance for most Asians due to its lower minor allele frequency. Polymorphisms of ITPA had no association with the dose of 6-MP and hepatotoxicity as shown in previous reports among Asians.11, 23 Genotyping of TPMT and ITPA among Asians seems statistically not a good clinical predictor for 6-MP dosage because of its low minor allele frequency or low influence among Japanese.

Among patients with TPMT lower activity, those given doses of 6-MP lower than 50 mg m−2 per day had a higher risk for relapse than those given 75 mg m−2 per day of 6-MP, (19.7% vs 6.7%).24 Therefore, we have to consider whether reduced dose administration of 6-MP due to the variant allele in NUDT15 could cause disease relapse. The previous study reported that after exposure to 6-MP for 24 h in leukemia cell culture experiments, the viable cell number was lower among the NUDT15-mutant cells than cells with wild-type.19 Also, the levels of the apoptosis markers were increased in NUDT15-mutant cells compared with control cells. Considering this report, NUDT15 variant may affect cell apoptosis not only in normal myeloid cells but also in leukemia cells. Because only three patients experienced disease relapse during the follow-up period, it was unclear whether thiopurine intolerance with NUDT15 polymorphisms could be related to disease relapse or not. However, considering the function of NUDT15, we hypothesized that there could be no significant association between dose reduction due to the variant of NUDT15 and disease relapse.

As NUDT15 have an anti-mutagenic activity,20, 21 patients with variant allele could have leukemogenesis as their constitution. Because the minor allele frequency of NUDT15 c.415C>T in children with ALL and the Japanese general population was not different in our study (P=1.00), we did not find significant association between the polymorphism at NUDT15 and leukemogenesis.

This study was not large enough to detect patients homozygous for the variant allele and was smaller than other studies. Despite this limitation, our study shows that 6-MP reduction is significant in the younger age group in relation to NUDT15 variant. Because of many factors associated with the dose of 6-MP such as age and gene polymorphisms including NUDT15, TPMT, ITPA and others, a prospective nationwide large cohort and a multivariate analysis is needed to clarify the relation among them.

Conclusion

The average administrated dose of 6-MP in ALL patients with NUDT15 variant allele (c.415C>T, p.Arg139Cys, rs116855232) was lower than in those with homozygote for the wild-type allele in maintenance therapy in the younger age group. The analysis with stratification by age might be useful in pharmacogenomics research among children.

References

Yokoi, T. Essentials for starting a pediatric clinical study (1): Pharmacokinetics in children. J. Toxicol. Sci. 34 (Suppl 2), Sp307–Sp312 (2009).

Roden, D. M., Wilke, R. A., Kroemer, H. K. & Stein, C. M. Pharmacogenomics: the genetics of variable drug responses. Circulation 123, 1661–1670 (2011).

Fanta, S., Niemi, M., Jonsson, S., Karlsson, M. O., Holmberg, C., Neuvonen, P. J. et al. Pharmacogenetics of cyclosporine in children suggests an age-dependent influence of ABCB1 polymorphisms. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 18, 77–90 (2008).

Yang, L. & Fujimoto, J. Childhood cancer mortality in Japan, 1980-2013. BMC Cancer 15, 446 (2015).

Horibe, K., Saito, A. M., Takimoto, T., Tsuchida, M., Manabe, A., Shima, M. et al. Incidence and survival rates of hematological malignancies in Japanese children and adolescents (2006-2010): based on registry data from the Japanese Society of Pediatric Hematology. Int. J. Hematol. 98, 74–88 (2013).

Manabe, A., Ohara, A., Hasegawa, D., Koh, K., Saito, T., Kiyokawa, N. et al. Significance of the complete clearance of peripheral blasts after 7 days of prednisolone treatment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Tokyo Children's Cancer Study Group Study L99-15. Haematologica 93, 1155–1160 (2008).

Moricke, A., Zimmermann, M., Reiter, A., Henze, G., Schrauder, A., Gadner, H. et al. Long-term results of five consecutive trials in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia performed by the ALL-BFM study group from 1981 to 2000. Leukemia 24, 265–284 (2010).

D'Avolio, A., De Nicolo, A., Cusato, J., Ciancio, A., Boglione, L., Strona, S. et al. Association of ITPA polymorphisms rs6051702/rs1127354 instead of rs7270101/rs1127354 as predictor of ribavirin-associated anemia in chronic hepatitis C treated patients. Antiviral. Res. 100, 114–119 (2013).

Lennard, L., Cartwright, C. S., Wade, R. & Vora, A. Thiopurine methyltransferase and treatment outcome in the UK acute lymphoblastic leukaemia trial ALL2003. Br. J. Haematol. 170, 550–558 (2015).

Zeglam, H. B., Benhamer, A., Aboud, A., Rtemi, H., Mattardi, M., Saleh, S. S. et al. Polymorphisms of the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene among the Libyan population. Libyan J. Med. 10, 27053 (2015).

Kim, H., Kang, H. J., Kim, H. J., Jang, M. K., Kim, N. H., Oh, Y. et al. Pharmacogenetic analysis of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a possible association between survival rate and ITPA polymorphism. PLoS ONE 7, e45558 (2012).

Tanaka, Y., Kato, M., Hasegawa, D., Urayama, K. Y., Nakadate, H., Kondoh, K. et al. Susceptibility to 6-MP toxicity conferred by a NUDT15 variant in Japanese children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 171, 109–115 (2015).

Suzuki, R., Fukushima, H., Noguchi, E., Tsuchida, M., Kiyokawa, N., Koike, K. et al. Influence of SLCO1B1 polymorphism on maintenance therapy for childhood leukemia. Pediatr. Int. 57, 572–577 (2015).

Moriyama, T., Nishii, R., Perez-Andreu, V., Yang, W., Klussmann, F. A., Zhao, X. et al. NUDT15 polymorphisms alter thiopurine metabolism and hematopoietic toxicity. Nat. Genet. 48, 367–373 (2016).

Igarashi, S., Manabe, A., Ohara, A., Kumagai, M., Saito, T., Okimoto, Y. et al. No advantage of dexamethasone over prednisolone for the outcome of standard- and intermediate-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Tokyo Children's Cancer Study Group L95-14 protocol. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 6489–6498 (2005).

Japanese genetic variation consortium. A reference database of genetic variations in Japanese population. in preparation http://www.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SnpDB. Accessed on 7 (July 2015).

Kakuta, Y., Naito, T., Onodera, M., Kuroha, M., Kimura, T., Shiga, H. et al. NUDT15 R139C causes thiopurine-induced early severe hair loss and leukopenia in Japanese patients with IBD. Pharmacogenomics J. (e-pub ahead of print 16 June 2015; doi:10.1038/tpj.2015.43).

Yang, J. J., Landier, W., Yang, W., Liu, C., Hageman, L., Cheng, C. et al. Inherited NUDT15 variant is a genetic determinant of mercaptopurine intolerance in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1235–1242 (2015).

Yang, S. K., Hong, M., Baek, J., Choi, H., Zhao, W., Jung, Y. et al. A common missense variant in NUDT15 confers susceptibility to thiopurine-induced leukopenia. Nat. Genet. 46, 1017–1020 (2014).

Hori, M., Satou, K., Harashima, H. & Kamiya, H. Suppression of mutagenesis by 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine 5'-triphosphate (7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine 5'-triphosphate) by human MTH1, MTH2, and NUDT5. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 1197–1201 (2010).

Takagi, Y., Setoyama, D., Ito, R., Kamiya, H., Yamagata, Y. & Sekiguchi, M. Human MTH3 (NUDT18) protein hydrolyzes oxidized forms of guanosine and deoxyguanosine diphosphates: comparison with MTH1 and MTH2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21541–21549 (2012).

Kubota, T. & Chiba, K. Frequencies of thiopurine S-methyltransferase mutant alleles (TPMT*2, *3A, *3B and *3C) in 151 healthy Japanese subjects and the inheritance of TPMT*3C in the family of a propositus. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 51, 475–477 (2001).

Wan Rosalina, W. R., Teh, L. K., Mohamad, N., Nasir, A., Yusoff, R., Baba, A. A. et al. Polymorphism of ITPA 94C>A and risk of adverse effects among patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated with 6-mercaptopurine. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 37, 237–241 (2012).

Levinsen, M., Rotevatn, E. O., Rosthoj, S., Nersting, J., Abrahamsson, J., Appell, M. L. et al. Pharmacogenetically based dosing of thiopurines in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: influence on cure rates and risk of second cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 61, 797–802 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Center for Child Health and Development (25-2). We thank Mr Charles N Jones for scientific writing assistance and Ms Tanabe Y for her technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, H., Fukushima, H., Suzuki, R. et al. Genotyping NUDT15 can predict the dose reduction of 6-MP for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia especially at a preschool age. J Hum Genet 61, 797–801 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2016.55

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2016.55

This article is cited by

-

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia mercaptopurine intolerance is associated with NUDT15 variants

Pediatric Research (2021)

-

Determination of NUDT15 variants by targeted sequencing can identify compound heterozygosity in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Association of NUDT15 c.415C>T allele and thiopurine-induced leukocytopenia in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2018)

-

Role of TPMT and ITPA variants in mercaptopurine disposition

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2018)