Abstract

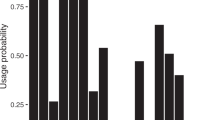

Parabens and phthalates are potential endocrine disruptors frequently used in personal care/beauty products, and the developing fetus may be sensitive to these chemicals. We measured urinary butyl-paraben (BP), methyl-paraben, propyl-paraben, mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP), and monoethyl phthalate (MEP) concentrations up to three times in 177 pregnant women from a fertility clinic in Boston, MA. Using linear mixed models, we examined the relationship between self-reported personal care product use in the previous 24 h and urinary paraben and phthalate metabolite concentrations. Lotion, cosmetic, and cologne/perfume use were associated with the greatest increases in the molar sum of phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations, although the magnitude of individual biomarker increases varied by product used. For example, women who used lotion had BP concentrations 111% higher (95% confidence interval (CI): 41%, 216%) than non-users, whereas their MBP concentrations were only 28% higher (CI: 2%, 62%). Women using cologne/perfume had MEP concentrations 167% (CI: 98%, 261%) higher than non-users, but BP concentrations were similar. We observed a monotonic dose–response relationship between the total number of products used and urinary paraben and phthalate metabolite concentrations. These results suggest that questionnaire data may be useful for assessing exposure to a mixture of chemicals from personal care products during pregnancy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BP:

-

butyl-paraben

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DBP:

-

dibutyl phthalate

- DEP:

-

diethyl phthalate

- EDC:

-

endocrine-disrupting compound

- MBP:

-

mono-n-butyl phthalate

- MEP:

-

monoethyl phthalate

- MP:

-

methyl-paraben

- PP:

-

propyl-paraben

- SG:

-

specific gravity

References

Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA . Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 935–943.

Shen X, Wu S, Yan C . Impacts of low-level lead exposure on development of children: recent studies in China. Clin Chim Acta 2001; 313: 217–220.

Calafat AM, Wong LY, Ye X, Reidy JA, Needham LL . Concentrations of the sunscreen agent benzophenone-3 in residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003—2004. Environ Health Perspect 2008; 116: 893–897.

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Bishop AM, Needham LL . Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the U.S. population: NHANES 2005-2006. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 679–685.

Silva MJ, Barr DB, Reidy JA, Malek NA, Hodge CC, Caudill SP et al. Urinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2000. Environ Health Perspect 2004; 112: 331–338.

Rice D, Barone S, Jr. . Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect 2000; 108 (Suppl 3): 511–533.

Andersen A . Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben,iIsopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol 2008; 27 (Suppl 4): 1–82.

Boberg J, Taxvig C, Christiansen S, Hass U . Possible endocrine disrupting effects of parabens and their metabolites. Reprod Toxicol (Elmsford, NY) 2010; 30: 301–312.

Oishi S . Effects of propyl paraben on the male reproductive system. Food Chem Toxicol 2002; 40: 1807–1813.

Oishi S . Effects of butyl paraben on the male reproductive system in mice. Arch Toxicol 2002; 76: 423–429.

Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, Ashby J, Sumpter JP . Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998; 153: 12–19.

Shirai S, Suzuki Y, Yoshinaga J, Shiraishi H, Mizumoto Y . Urinary excretion of parabens in pregnant Japanese women. Reprod Toxicol (Elmsford, NY) 2012; 35: 96–101.

Koo HJ, Lee BM . Estimated exposure to phthalates in cosmetics and risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health 2004; 67: 1901–1914.

Howdeshell KL, Wilson VS, Furr J, Lambright CR, Rider CV, Blystone CR et al. A mixture of five phthalate esters inhibits fetal testicular testosterone production in the sprague-dawley rat in a cumulative, dose-additive manner. Toxicol Sci 2008; 105: 153–165.

Harris CA, Henttu P, Parker MG, Sumpter JP . The estrogenic activity of phthalate esters in vitro. Environ Health Perspect 1997; 105: 802–811.

Engel SM, Miodovnik A, Canfield RL, Zhu C, Silva MJ, Calafat AM et al. Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with childhood behavior and executive functioning. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 565–571.

Miodovnik A, Engel SM, Zhu C, Ye X, Soorya LV, Silva MJ et al. Endocrine disruptors and childhood social impairment. Neurotoxicology 2011; 32: 261–267.

Swan SH, Main KM, Liu F, Stewart SL, Kruse RL, Calafat AM et al. Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 1056–1061.

Whyatt RM, Liu X, Rauh VA, Calafat AM, Just AC, Hoepner L et al. Maternal prenatal urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and child mental, psychomotor, and behavioral development at 3 years of age. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 290–295.

Buckley JP, Palmieri RT, Matuszewski JM, Herring AH, Baird DD, Hartmann KE et al. Consumer product exposures associated with urinary phthalate levels in pregnant women. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 22: 468–475.

Duty SM, Ackerman RM, Calafat AM, Hauser R . Personal care product use predicts urinary concentrations of some phthalate monoesters. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 1530–1535.

Janjua NR, Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, Wulf HC, Andersson AM . Urinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humans. Int J Androl 2008; 31: 118–130.

Just AC, Adibi JJ, Rundle AG, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Hauser R et al. Urinary and air phthalate concentrations and self-reported use of personal care products among minority pregnant women in New York city. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2010; 20: 625–633.

Romero-Franco M, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Calafat AM, Cebrian ME, Needham LL, Teitelbaum S et al. Personal care product use and urinary levels of phthalate metabolites in Mexican women. Environ Int 2011; 37: 867–871.

Silva E, Rajapakse N, Kortenkamp A . Something from "nothing"—eight weak estrogenic chemicals combined at concentrations below NOECs produce significant mixture effects. Environ Sci Technol 2002; 36: 1751–1756.

Braun JM, Smith KW, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Berry K, Ehrlich S et al. Variability of urinary phthalate metabolite and bisphenol A concentrations before and during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 739–745.

Smith KW, Braun JM, Williams PL, Ehrlich S, Correia KF, Calafat AM et al. Predictors and variability of urinary paraben concentrations in men and women, including before and during Pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 1538–1543.

Silva MJ, Samandar E, Preau JL, Jr., Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM . Quantification of 22 phthalate metabolites in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2007; 860: 106–112.

Ye X, Bishop AM, Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM . Parabens as urinary biomarkers of exposure in humans. Environ Health Perspect 2006; 114: 1843–1846.

Ye X, Bishop AM, Needham LL, Calafat AM . Automated on-line column-switching HPLC-MS/MS method with peak focusing for measuring parabens, triclosan, and other environmental phenols in human milk. Anal Chim Acta 2008; 622: 150–156.

Hornung RW, Reed LD . Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Appl Occup Environ Hygiene 1990; 5: 46–51.

CDC 2012 C.f.D.C.a.P. NHANES-Whats New http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/new_nhanes.htm#Jan12, 2012. Accessed January 2012.

Safe SH . Hazard and risk assessment of chemical mixtures using the toxic equivalency factor approach. Environ Health Perspect 1998; 106 (Suppl 4): 1051–1058.

Wild CP . Complementing the genome with an "exposome": the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 1847–1850.

Adibi JJ, Whyatt RM, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Camann D, Herrick R et al. Characterization of phthalate exposure among pregnant women assessed by repeat air and urine samples. Environ Health Perspect 2008; 116: 467–473.

Casas L, Fernandez MF, Llop S, Guxens M, Ballester F, Olea N et al. Urinary concentrations of phthalates and phenols in a population of Spanish pregnant women and children. Environ Int 2011; 37: 858–866.

Philippat C, Mortamais M, Chevrier C, Petit C, Calafat AM, Ye X et al. Exposure to phthalates and phenols during pregnancy and offspring size at birth. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 120: 464–470.

Shen HY, Jiang HL, Mao HL, Pan G, Zhou L, Cao YF . Simultaneous determination of seven phthalates and four parabens in cosmetic products using HPLC-DAD and GC–MS methods. J Sep Sci 2007; 30: 48–54.

Ye X, Pierik FH, Hauser R, Duty S, Angerer J, Park MM et al. Urinary metabolite concentrations of organophosphorous pesticides, bisphenol A, and phthalates among pregnant women in Rotterdam, the Netherlands: the Generation R study. Environ Res 2008; 108: 260–267.

Hubinger JC . A survey of phthalate esters in consumer cosmetic products. J Cosmet Sci 2010; 61: 457–465.

Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH . Women's exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 23: 197–206.

Meeker JD, Cantonwine D, Rivera-Gonzalez LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM et al. Distribution, variability and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol 2013; 47: 3439–3447.

Howdeshell KL, Furr J, Lambright CR, Wilson VS, Ryan BC, Gray LE, Jr. . Gestational and lactational exposure to ethinyl estradiol, but not bisphenol A, decreases androgen-dependent reproductive organ weights and epididymal sperm abundance in the male long evans hooded rat. Toxicol Sci 2008; 102: 371–382.

Sagiv SK, Thurston SW, Bellinger DC, Tolbert PE, Altshul LM, Korrick SA . Prenatal organochlorine exposure and behaviors associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171: 593–601.

Loretz L, Api AM, Barraj L, Burdick J, Davis de A, Dressler W et al. Exposure data for personal care products: hairspray, spray perfume, liquid foundation, shampoo, body wash, and solid antiperspirant. Food Chem Toxicol 2006; 44: 2008–2018.

Loretz LJ, Api AM, Barraj LM, Burdick J, Dressler WE, Gettings SD et al. Exposure data for cosmetic products: lipstick, body lotion, and face cream. Food Chem Toxicol 2005; 43: 279–291.

Bennett DH, Wu XM, Teague CH, Lee K, Cassady DL, Ritz B et al. Passive sampling methods to determine household and personal care product use. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 22: 148–160.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the technical assistance of M. Silva, E. Samandar, J. Preau, X. Ye, X. Zhou, R. Hennings, and J. Tao (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)) in measuring the urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and parabens. This work was funded by NIEHS grants T32 ES007069, R01 ES009718, P30 ES000002, and R00 ES020346.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braun, J., Just, A., Williams, P. et al. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 24, 459–466 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2013.69

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2013.69

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Personal care product use patterns in association with phthalate and replacement biomarkers across pregnancy

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2024)

-

Occupational differences in personal care product use and urinary concentration of endocrine disrupting chemicals by gender

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2023)

-

Interventions to Reduce Exposure to Synthetic Phenols and Phthalates from Dietary Intake and Personal Care Products: a Scoping Review

Current Environmental Health Reports (2023)

-

Influence of living in the same home on biomonitored levels of consumer product chemicals

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2022)

-

Chemical exposures assessed via silicone wristbands and endogenous plasma metabolomics during pregnancy

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2022)