Abstract

The nitrogen (N)-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium is globally distributed in warm, oligotrophic oceans, where it contributes a substantial proportion of new N and fuels primary production. These photoautotrophs form macroscopic colonies that serve as relatively nutrient-rich substrates that are colonized by many other organisms. The nature of these associations may modulate ocean N and carbon (C) cycling, and can offer insights into marine co-evolutionary mechanisms. Here we integrate multiple omics-based and experimental approaches to investigate Trichodesmium-associated bacterial consortia in both laboratory cultures and natural environmental samples. These efforts have identified the conserved presence of a species of Gammaproteobacteria (Alteromonas macleodii), and enabled the assembly of a near-complete, representative genome. Interorganismal comparative genomics between A. macleodii and Trichodesmium reveal potential interactions that may contribute to the maintenance of this association involving iron and phosphorus acquisition, vitamin B12 exchange, small C compound catabolism, and detoxification of reactive oxygen species. These results identify what may be a keystone organism within Trichodesmium consortia and support the idea that functional selection has a major role in structuring associated microbial communities. These interactions, along with likely many others, may facilitate Trichodesmium’s unique open-ocean lifestyle, and could have broad implications for oligotrophic ecosystems and elemental cycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most primary producers are associated with a heterotrophic community, often through physical attachment and direct colonization (Nausch, 1996; Fisher et al., 1998; Sapp et al., 2007; Hmelo et al., 2012). A common feature of these associations is the passive transfer from host to epibiont of organic carbon (C), and in the case of diazotrophs such as Trichodesmium, reduced nitrogen (N) (Mulholland et al., 2006). These assemblages provide a dynamic interorganismal interface wherein, despite some likely competitive interactions (Amin et al., 2012), many relationships have been found to be mutualistic. For example, epibionts can assist their host through the acquisition of trace metals or other nutrients, reduction of local concentrations of hazardous compounds, and secretion of anti-biofouling agents (Paerl and Pinckney, 1996; Morris et al., 2008; Bertrand and Allen, 2012; Beliaev et al., 2014; Bertrand et al., 2015). Elucidating the nature of these interactions and their consequent modulation of host/colony elemental fluxes is integral to developing a complete understanding of marine biogeochemical cycling.

At a broad taxonomic level, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes have been consistently found in association with many photoautotrophs (Fisher et al., 1998; Sapp et al., 2007; Amin et al., 2012; Bertrand et al., 2015), including Trichodesmium (Hewson et al., 2009; Hmelo et al., 2012; Rouco et al., 2016), likely because of general lifestyle characteristics such as attachment and opportunism (Hmelo et al., 2012). There has also been evidence supporting host-specific associations at finer taxonomic resolutions within these clades (Stevenson and Waterbury, 2006; Lachnit et al., 2009; Guannel et al., 2011; Sison-mangus et al., 2014). For instance, heterotrophs co-occurring with the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia have been shown to vary as a function of host species and toxicity (Guannel et al., 2011)—with some epibionts being mutualistic with regard to their native host, yet parasitic to others (Sison-mangus et al., 2014). Such organismal-specific mutualistic relationships are believed to have developed through co-evolutionary histories (Stevenson and Waterbury, 2006; Amin et al., 2012; Sison-mangus et al., 2014). The recently proposed Black Queen Hypothesis (BQH) (Morris et al., 2012) offers a mechanistic framework that could drive such interweavings of evolutionary paths. The BQH is built upon two main suppositions: (1) certain bacterial functions are ‘leaky’, meaning they can affect or be used by nearby organisms, and are therefore considered ‘public goods’ (for example, the exudation of fixed C by photoautotrophs); and (2) organisms making use of these public goods may then experience a positive selective pressure resulting in the loss of their own costly pathways responsible for those particular goods (Morris et al., 2012; Sachs and Hollowell, 2012). This process is anticipated to leave in its wake various interorganismal dependencies that can guide community structure and ultimately lead to highly specific associations (Sachs and Hollowell, 2012; Morris, 2015).

Trichodesmium spp. are notoriously difficult to maintain in culture (Paerl et al., 1989; Waterbury, 2006). It has been suggested that this is perhaps in part because of the existence of obligate dependencies between host and epibiont (Paerl et al., 1989; Zehr, 1995; Waterbury, 2006; Hmelo et al., 2012). However, the extent to which the interactions between Trichodesmium and their consortia modulate Trichodesmium physiology and N2 fixation remains largely unstudied, despite having long been recognized as significant (Borstad, 1978; O’Neil and Roman, 1992).

Here we investigate microbial communities associated with Trichodesmium spp. in laboratory enrichments and natural environmental samples, and present a highly conserved association found to be present in both laboratory samples and in situ. We then use an interorganismal comparative genomics approach to generate genetic-based hypotheses as to what interactions may be contributing to the maintenance of these organisms’ co-occurrence.

Materials and methods

Nucleic acid extractions

DNA extractions were performed for this study for tag analysis only. All other data sets were attained from prior studies (detailed in Supplementary Table S1). Extractions utilized the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For enrichments currently maintained, ~75 ml were filtered onto 5 μm polycarbonate Nucleopore filters (Whatman, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Filters were placed directly into lysis tubes of extraction kit. Protocol blanks (nothing added to lysis tubes) were performed to track potential kit-introduced contamination.

Tag data sequencing and analysis

DNA from the 11 samples extracted for this study (plus two blanks) was sent for sequencing by a commercial vender (Molecular Research LP, MR DNA, Shallowater, TX, USA). Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) MiSeq paired-end (2 × 300 bp) sequencing was performed with primers targeting the V4V5 region of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene (515f: 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′; 926r: 5′-CCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT-3′; Parada et al., 2015). Library preparation and sequencing was carried out at the facility following Illumina library preparation protocols.

Tag data curation and initial merging of paired reads were performed within mothur v.1.36.1 (Schloss et al., 2009) following the mothur Illumina MiSeq Standard Operating Procedure (Kozich et al., 2013). These merged and quality-filtered sequences were demultiplexed, primers trimmed, and contigs clustered using Minimum Entropy Decomposition (MED) (Eren et al., 2014). MED is an unsupervised, non-alignment-based algorithm that enables single-nucleotide resolution when segregating amplicon sequences. This has been shown to often result in biologically relevant representative sequences (referred to herein as ‘oligotypes’) more similar than traditional techniques of clustering operational taxonomic units can achieve—even at 99% ID similarity (Eren et al., 2013; Mclellan et al., 2013). Six ‘non-Trichodesmium’, particle-size fraction samples previously sequenced with the same primers (Parada et al., 2015) were added to our data set before clustering with MED in order to address and negate the possibility of the ubiquitous presence of any oligotypes. Extraction blanks (no sample or DNA added to DNA lysis tubes) were used to identify and remove potential contaminants resulting from the lab or extraction kit as described previously (Lee et al., 2015).

Other 16S rRNA sequences used in this study included heterotrophs isolated from Trichodesmium cultures (see below), a clone library study of associated epibionts of natural colonies (Hmelo et al., 2012), 16S rRNA sequences derived from an environmental Trichodesmium metagenomic sample from the Sargasso Sea (Walworth et al., 2015) and a recent marker-gene study (Rouco et al., 2016). These sequences were trimmed to cover only the V4V5 region with mothur v.1.36.1 (Schloss et al., 2009) by aligning to the mothur-recreated Silva SEED database v119 and then trimming to targeted region using database positions 11895:28464. These and the recovered oligotypes from this study were then aligned in Geneious v.9.0.5 (Kearse et al., 2012), using Muscle (Edgar, 2004) with default settings, and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with the PhyML plug-in v.2.2.0 (default settings, 100 bootstraps). In silico analysis of the primers utilized in the Hmelo et al. (2012) clone library study was done with the web-based ‘PCR Products’ tool (www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/pcr_products.html; Stothard, 2000).

Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing and analysis

Various data sets from multiple sources were used in this study and are described in Supplementary Table S1, with further information presented in Supplementary Table S2. Five metagenomic data sets from a long-term Trichodesmium CO2 manipulation experiment, presented elsewhere (Hutchins et al., 2015), were generated through sequencing performed at USC’s Epigenome Center (Los Angeles, CA, USA). DNA from these samples was previously extracted with the MoBio DNA PowerPlant kit (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and sequenced with Illumina’s HiSeq (2 × 50 bp) with a 300-bp insert. Raw data were quality-filtered (minimum quality 20, minimum length 35) with the FASTX-toolkit (hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/).

The quality-filtered forward and reverse reads from the five metagenomic data sets from the long-term Trichodesmium CO2 experiment (Hutchins et al., 2015) were concatenated, interleaved, and co-assembled with IDBA-UD v.1.1.1 (Peng et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table S3 contains co-assembly statistics). Coverage profiles were generated for each of the five original metagenomes by mapping them to the co-assembly with Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Metagenomic binning (clustering contigs into representative genomes) was carried out using the analysis and visualization platform Anvi’o (Eren et al., 2015). Anvi’o utilizes CONCOCT (Alneberg et al., 2014), based on coverage and tetranucleotide composition, to perform an initial unsupervised clustering of contigs, and then allows for human-guided curation. Available environmental Trichodesmium metagenomic (Walworth et al., 2015) and metatranscriptomic (Hewson et al., 2009) data sets were subsequently mapped to these bins to investigate their environmental significance.

Refinement of Alteromonas macleodii bin

To improve our representative genome of A. macleodii, we mapped all five of the metagenomes used in the co-assembly to our A. macleodii bin recovered from Anvi’o. Only reads that successfully mapped were then subsequently assembled with the SPAdes genome assembler v.3.8.1 (Bankevich et al., 2012). Comparing these two bins with QUAST (v.4.1) (Gurevich et al., 2013) revealed this process yielded a higher-quality assembly (Supplementary Table S4), and this refined A. macleodii bin was utilized in subsequent analyses.

Identification of genes/gene clusters within A. macleodii bin

The genetic potential for siderophore and acyl-homoserine lactone production was identified by way of the web-based tool AntiSmash (Weber et al., 2015); this uses well-curated Hidden Markov Models to identify gene clusters involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis and transport. All other genes were identified through BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) or Hidden Markov Model searches (HMMER v.3.1b2) of profiles built from reference sequences as presented in Supplementary Table S5.

Isolation of heterotrophs from Trichodesmium

Epibionts were isolated from Trichodesmium cultures using a soft agar RMP medium with the following modifications: 5 g of agarose added to 250 ml MilliQ water before autoclaving, and a sterile addition of 0.3% methanol, final concentration, was added post-autoclaving and cooled to 50 °C before plates were poured. Trichodesmium cultivars of A. macleodii, A020, A021 and A029, were isolated from T. erythraeum K-11#131 by inoculating colonies onto the solid RMP-methanol medium using a sterile loop and incubating at 27 °C under a 14:10 light:dark regime (100 μM m−2 s−1). Trichodesmium filaments were motile in the soft agar medium leaving trails of epibionts after 7–10 days. Sections of enriched trails were excised using a sterile scalpel and inoculated onto fresh RMP-methanol agar. Individual colonies were isolated and grown in liquid RMP-methanol medium containing 0.1% tryptone and cryopreserved in 10% dimethylsulfoxide at −80 °C.

Siderophore production assay

Chrome azurol S plates were used to screen for siderophore production as described previously (Schwyn and Neilands, 1987).

DMSP analysis

The production of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) by T. erythraeum IMS101 was measured in replete, phosphorus (P)-limited, and iron (Fe)-limited conditions. Enrichments were grown in 1 l of YBC-II media (Chen et al., 1996) in 2 l polycarbonate baffled flasks at 26 °C under a 14:10 light:dark cycle (150 μM m−2 s−1) with fluorescent light. Enrichments were continuously shaken to avoid cell sedimentation. Before analysis of DMSP production, nutrient-limited cultures were semi-continuously acclimated to nutrient conditions (P-limited was 25 × lower than replete and Fe-limited had no Fe added). Limitation was confirmed via growth rates. DMSP was sampled in all cultures on day 10.

DMSP was measured as dimethylsulfide (DMS) on a custom Shimadzu GC-2014 equipped with a flame photometric detector and a Chromosil 330 packed column. Briefly, DMSP was cleaved to DMS via alkaline hydrolysis using 5 m NaOH and pre-concentrated using a liquid-N purge-and-trap method following a modified protocol (Kiene and Service, 1991). Samples for chlorophyll-a were filtered on GF/F filters, extracted in 90% acetone and measured on a Turner Trilogy (San Jose, CA, USA) fluorometer. See supplemental text for further discussion.

Accession information

Accession numbers for previously deposited data sets are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The tag data generated herein have been uploaded to NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP078329. The five metagenomes from the Trichodesmium long-term CO2 manipulation experiment (Hutchins et al., 2015) have been deposited in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive under SRP078343. The draft genome of A. macleodii has been deposited in NCBI’s Whole Genome Shotgun database under accession MBSN00000000. Clone library sequences of isolates from Trichodesmium are available through NCBI’s GenBank, accession numbers KX519544–KX519550.

Results and Discussion

The microbial composition of Trichodesmium consortia

Trichodesmium-associated communities were initially investigated via 16S rRNA gene sequencing performed on 11 samples spanning two species and multiple strains. These included several distinct laboratory-maintained cultures and an environmental sample of handpicked and washed individual Trichodesmium colonies (Webb et al., 2007) (Supplementary Table S1). Consistent with prior studies (Hewson et al., 2009; Hmelo et al., 2012), at a broad taxonomic level this revealed a predominance of sequences sourced from Bacteroidetes, Gammaproteobacteria, and Alphaproteobacteria (Supplementary Data Set S1; Supplementary Table S6). By clustering sequences with single-nucleotide resolution (Eren et al., 2014) into groups, herein referred to as ‘oligotypes’, we identified several identical sequences (100% similarity over the ~370-bp region sequenced; highlighted in Supplementary Table S6) as present in all Trichodesmium samples (n=11), yet absent from ‘non-Trichodesmium’ samples (n=6; consisting of particle-size fraction environmental data sets previously generated utilizing the same primers; Parada et al., 2015). Subsequently aligning these conserved oligotypes (those present in all of our samples) to sequences previously recovered from various other environmental Trichodesmium samples revealed highly similar sequences detected in all sources, and clusters of identical ones within the Gammaproteobacteria (Figure 1). These identical sequences, originating from A. macleodii, were acquired from samples collected independently by different researchers at different times and locations, including an environmental metagenome, and were generated by way of three different sequencing technologies (Figure 1 legend). In light of these results, and genome-level evidence of co-occurrence in natural environmental samples presented in the following section, herein we focus on the A. macleodii association with Trichodesmium. In this vein, we leveraged a recently published study investigating environmental Trichodesmium epibionts in both the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean using tag sequencing from handpicked and washed colonies (Rouco et al., 2016). Processing that data set with single-nucleotide resolution clustering (Eren et al., 2014) reveals our A. macleodii oligotypes are present in 25 of the 27 samples surveyed (100% identical across the shared ~280 bp between the data sets) comprising <1–5% of reads recovered, including Trichodesmium; these data further demonstrate the broadly conserved presence of these A. macleodii sequences in situ. The two samples lacking A. macleodii were out of 10 from the same sampling site, in the North Pacific, whereas all other 8 contained them. It is therefore possible they were simply below detection and/or underrepresented during the initial PCR. Furthermore, Alteromonas has recently been observed to disproportionally contribute to global transcripts, with gene expression being ~10-fold higher than genetic abundance (Dupont et al., 2015)—that is, low relative abundance does not necessarily suggest low activity.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA genes depicting only closely related sequences recovered from Trichodesmium-associated communities of various samples. Colored leaf labels represent the sequence source: blue=tag sequences from this study, included are only those identical sequences that were found to be present in all 11 Trichodesmium samples analyzed*; orange=Sanger sequences from organisms isolated directly from individual Trichodesmium colonies; green=Sanger sequences from a Trichodesmium-associated community clone library study (Hmelo et al., 2012; while this study did not detect A. macleodii, in silico analysis of the primers utilized revealed they would not have amplified these sequences); and red=16S rRNA sequences mined from a metagenomic assembly of an environmental Trichodesmium sample (Walworth et al., 2015). *‘Oligotype 1923’ was present in 10/11 of the samples analyzed.

It is worth noting that all of the 16 ‘finished’ genomes of Alteromonas available through integrated microbial genomes (IMG) (Markowitz et al., 2009) possess five 16S rRNA gene copies, which are often not identical (although typically >99% similar). It is thus possible that the distinct sequences presented in Figure 1 within the A. macleodii clade (which vary only 1–2 bases over the ~370- bp sequenced) may actually be sourced from a single genome. Regardless, this marker-gene analysis revealed the consistent presence of identical sequences within associated consortia of many distinct laboratory-maintained and environmental Trichodesmium samples, suggesting a conserved association with A. macleodii.

Beyond a marker-gene: genome-level evidence of the co-occurrence of Trichodesmium and A. macleodii in situ

The striking ubiquity of these identical sequences across both environmental and laboratory-maintained samples suggested that Trichodesmium epibionts occurring in culture may be environmentally relevant, as opposed to being comprised solely of laboratory-derived contaminants. To investigate this beyond a single marker-gene, we leveraged available enrichment-derived metagenomic and metatranscriptomic (Walworth et al., 2015) data sets from the aforementioned long-term CO2 experiment (Hutchins et al., 2015; Supplementary Table S2). A co-assembly of five metagenomic data sets was performed in an effort to better access those organisms in low abundance (as Trichodesmium contributed ~96–99% of total reads), and the resulting contigs were clustered to identify representative genomes (Supplementary Data Set S2 for co-assembly fasta; Supplementary Table S3 for summary). Beyond Trichodesmium, this process enabled the recovery of three near-complete representative genomes (‘bins’) sourced from members of A. macleodii, Lewinella sp., and Synechococcus sp.—all estimated at >97% complete and <5% contamination (Supplementary Table S4).

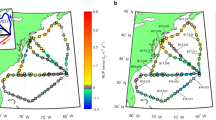

To assess if these bins were truly representative of organisms present within in situ Trichodesmium assemblages, we examined two publically available Trichodesmium-focused environmental data sets including the above-mentioned Sargasso Sea metagenome (Walworth et al., 2015) and a southwest Pacific Ocean metatranscriptome (Hewson et al., 2009). Mapping these data sets to our bins revealed extensive recruitment across our A. macleodii genome (Figure 2). As mapping is a highly stringent alignment process, this demonstrated the presence of a closely related A. macleodii, at the genomic level, present in both of these Trichodesmium environmental samples, yet absent from particle-size fraction ‘non-Trichodesmium’ samples (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure S1 for further discussion). This is particularly remarkable for the Sargasso Sea metagenomic sample as individual Trichodesmium colonies were handpicked and washed several times to remove any organisms not tightly associated—yet this closely related A. macleodii remained.

Visualization of laboratory enrichment and environmental metagenomic (DNA) and metatranscriptomic (RNA) reads mapped to our assembled representative genomic bins revealing the presence of a closely related A. macleodii in both environmental Trichodesmium samples (labeled ‘Tricho’), but absent from samples lacking Trichodesmium (‘non-Tricho’). A hierarchical clustering of contigs from the co-assembly is shown at the top segregating contigs into representative genomic bins as depicted by the four large colored columns and labeled at the bottom. Thin, vertical peaks display log transformed normalized coverage of reads (across that sample/row) mapped to that contig (column/leaf). ‘High’ and ‘low’ CO2 DNA and RNA samples mapping from the long-term experiment to these newly recovered bins revealed their presence and activity were maintained in both CO2 treatments, even after several hundred generations (Hutchins et al., 2015). SCB, Southern California Bight. See Supplementary Table S1 for detailed sample information.

It is worth emphasizing that these metagenomic bins were derived from a laboratory-maintained Trichodesmium erythraeum enrichment, strain IMS101, which was originally isolated ~25 years ago (Prufert-Bebout et al., 1993). Regardless of whether this cohabitation with A. macleodii has persisted over the entire time IMS101 has been in culture, or if the organism was introduced as a ‘contaminant’ at some point in the strain’s long cultivation history (~3500 generations) and subsequently maintained, its co-occurrence in these laboratory enrichments and in the environment in 28/30 available samples (evidenced by marker-gene analysis and at the genome level) intimates a robust stability of this association. It is also important to note that while this relationship may not be exclusive, as A. macleodii is commonly observed in association with other photoautotrophs (Morris et al., 2008; Biller et al., 2015), collectively these data suggest Trichodesmium colonies may consistently harbor A. macleodii—a finding with significant implications regarding our understanding of Trichodesmium’s physiology. As phytoplankton-associated communities are understood to be structured by functional and characteristic properties of host and epibiont (Stevenson and Waterbury, 2006; Guannel et al., 2011; Lachnit et al., 2011; Sison-mangus et al., 2014), this conserved association of Trichodesmium with A. macleodii may in part be maintained by interorganismal interactions.

Genomic signatures of potential interactions

If this co-occurrence of Trichodesmium and A. macleodii is being maintained because of specific interactions, then, as predicted by the BQH, there should exist corresponding genetic signatures underlying them. In considering the implications of the BQH, Sachs and Hollowell (2012) recently noted: ‘This new paradigm suggests that bacteria may often form interdependent cooperative interactions in communities and moreover that bacterial cooperation should leave a clear genomic signature via complementary loss of shared diffusible functions’.

Owing to its tight association with its epibiotic community, Trichodesmium is a prime candidate for evolutionary mechanisms such as those described by the BQH. Moreover, Trichodesmium has long been considered enigmatic because of its ability to carry out N2 fixation (with the O2-sensitive enzyme nitrogenase) while contemporaneously performing O2-evolving photosynthesis with no immediately apparent mechanism for keeping these two processes segregated (Carpenter and Price, 1976; Paerl et al., 1989; Zehr, 1995). It has been suggested that this may in part be because of interactions with its associated community. For example, host exudation of organic C supports associated heterotrophic growth and fuels respiration, which in turn can generate microenvironments of low O2 concentrations thereby reducing oxic inhibition of host N2 fixation (Paerl and Kellar, 1978; Paerl and Bebout, 1988; Paerl et al., 1989; Fay, 1992; Zehr, 1995; Paerl and Pinckney, 1996). This cascade of events benefits the consortium as a whole, and the development of such complex interorganismal networks has been argued to be a natural consequence of the BQH—while the underlying mechanism is certainly not driven by any such mutualisms, they will tend to emergently arise (Sachs and Hollowell, 2012; Morris, 2015).

As a first step toward assessing if any such mutualistic interactions may exist between Trichodesmium and A. macleodii, we applied an interorganismal comparative genomics approach in order to identify any potential interactions through their corresponding genomic footprints. By identifying these gene loss/retention patterns of shared diffusible functions, we provide here genetic-based evidence for potential interactions related to acquisition of Fe and P, vitamin B12 exchange, small C compound cycling, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification. Such genetic complementation in and of itself cannot provide firm evidence of mutualistic interdependencies, but does serve to generate hypotheses about possible host/epibiont interactive feedbacks and identifies promising avenues for future definitive studies of putative BQH relationships.

Fe acquisition

Fe is an essential micronutrient required for photosynthesis, respiration, and N2 fixation that is often limiting in marine environments (Vraspir and Butler, 2009; Chappell et al., 2012). One mechanism by which marine microbes overcome Fe limitation is through the production of extracellular, high-affinity Fe-binding molecules known as siderophores that scavenge Fe3+ from the surrounding environment (Amin et al., 2009). Although many siderophore/Fe complexes are highly stable and organismal specific (requiring selective outer membrane receptors and transporters for uptake), there is a subset produced in the marine environment that exhibit low organismal specificity and are highly photoreactive when bound to Fe3+ (Amin et al., 2009; Vraspir and Butler, 2009). These complexes become oxidized through ultraviolet photocatalysis whereby chelated Fe3+ is reduced and released as Fe2+, providing a substantial source of bioavailable Fe in the photic zone (Barbeau et al., 2001). The seemingly surprising observation that many organisms produce siderophores that so readily serve as ‘public goods’ has led to the suggestion that they may have been evolutionarily selected for as a result of bacterial–phytoplankton associations (Amin et al., 2009). Indeed, it has been shown that this process increases the Fe uptake of phytoplankton (Barbeau et al., 2001), and Synechococcus Fe limitation response transcripts have been shown to significantly decrease when co-cultured with a siderophore-producing strain of Shewanella (Beliaev et al., 2014).

Unlike several other cyanobacteria, Trichodesmium has not been shown to produce siderophores, and lacks any known genetic potential to do so (Chappell and Webb, 2010; Kranzler et al., 2011). However, in addition to mechanisms of ferric and ferrous inorganic Fe acquisition (Roe and Barbeau, 2014), Trichodesmium does appear to have the ability to take up Fe-siderophore complexes via several Ton-B components, tonB-exbB-exbD (Tery_1418, 4448 and 4449; Chappell and Webb, 2010; Kranzler et al., 2011). Consistent with BQH predictions of compensatory gene loss/retention within mutualistic relationships, our A. macleodii genomic bin possesses a gene cluster predicted to be responsible for the biosynthesis of aerobactin (Supplementary Table S5), a well-studied, low-affinity, highly photoreactive siderophore (Kupper et al., 2006). Transcripts for these genes were detected in the aforementioned long-term metatranscriptomes (Supplementary Table S5), and to further validate this genetic potential, we experimentally confirmed the production of siderophores by our A. macleodii isolates (A020, A021, A029 in Figure 1) via the chrome azurol S plate assay (Supplementary Figure S2). Furthermore, the exbB-exbD transporter components of the potential Trichodesmium uptake complex share homology with those found in the freshwater cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 (slr0677 and slr0678, at 67% similarity 85% positives and 54/71%, respectively; see Supplementary Figure S3 for alignments). In Synechocystis PCC6803, these genes have been shown to be essential for the reduction of Fe3+ bound to aerobactin just before the subsequent uptake of Fe2+ into the cell (Kranzler et al., 2011).

Although this evidence suggests that Trichodesmium may have the ability to obtain Fe bound to the aerobactin produced by A. macleodii, this hypothesis requires experimental investigation. Regardless, however, the photoreactivity of these siderophores and their low stability when ligated to Fe3+ clearly result in more available Fe as a public good for any nearby organisms (Amin et al., 2009).

Vitamin B12 exchange

B12 exchange has become a key example of inter-domain dependence within photoautotroph-heterotroph associations (Croft et al., 2005). Most of this research has focused on eukaryotes (which cannot synthesize B12 de novo; Bertrand and Allen, 2012), whereby biosynthesis of B12 by associated heterotrophs is followed by uptake by their algal host (Croft et al., 2005; Bertrand et al., 2015). In contrast to this commonly seen scenario, in our prokaryote/prokaryote association Trichodesmium can produce B12 de novo (Sañudo-Wilhelmy et al., 2014), whereas A. macleodii cannot. Despite lacking this capability, there is evidence our A. macleodii may be facultative with regard to the vitamin as it contains at least two B12-dependent enzymes: an epoxyqueosine reductase involved in tRNA modification; and a methionine synthetase, in addition to also containing a B12-independent version (Supplementary Table S5). It has been shown that bacteria capable of both methods of methionine production are often facultative, with the B12-dependent pathway being more efficient (Augustus and Spicer, 2011). As some marine cyanobacteria have been shown to exude B12 (Bonnet et al., 2010), and our A. macleodii bin also possesses genes identified as outer membrane receptors and active transporters of the vitamin (all found to be expressed, Supplementary Table S5), it is possible this epibiont may benefit from the exudation of B12 by Trichodesmium.

This hypothesized direction of B12 exchange (from photoautotrophic host to associated epibionts) is opposite to that commonly seen within eukaryotic algal-heterotroph associations (Croft et al., 2005; Bertrand et al., 2015). A general trend is therefore possible wherein heterotrophs that cannot synthesize B12 may tend to more often associate with prokaryotic photoautotrophs rather than their eukaryotic counterparts. To the best of our knowledge, such a relationship has yet to be investigated.

P acquisition

As a N fixer, Trichodesmium is believed to commonly be P limited, and has been shown to partially fulfill its P quota through the expression of alkaline phosphatases (Webb et al., 2007)—enzymes that cleave phosphate groups from organic P. In addition, it has been suggested that there may be selective pressure within Trichodesmium colonies for organisms possessing greater capabilities of P uptake (Hewson et al., 2009). The expression of alkaline phosphatases by members of Trichodesmium consortia has been previously observed, and these organisms are expected to ultimately be aiding their host with P acquisition (Hynes et al., 2009). Our A. macleodii does indeed possess the genetic potential to produce alkaline phosphatases, but moreover, it also possesses a secondary metabolite biosynthesis cluster predicted to produce acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs; Supplementary Table S5). AHLs are a class of molecules known to be involved in quorum sensing (Case et al., 2008), and have specifically been shown to double the activity of alkaline phosphatases upon addition to natural Trichodesmium colonies (Van Mooy et al., 2012). This genetic evidence suggests A. macleodii may be one of the organisms within Trichodesmium consortia helping to orchestrate the colonial acquisition of P, a major limiting nutrient to the host in situ. As AHLs can modulate many population-level cellular responses (Amin et al., 2012), it is likely these molecules are also coordinating much more than solely APase activity within these consortia.

Consortial C catabolism

For many phytoplankton, photosynthesis is believed to be C-limited in situ (Hein and Sand-Jensen, 1997). Consequently, they use C-concentrating mechanisms that, although energetically costly, are capable of generating intracellular CO2 concentrations up to 1000-fold higher than external levels (Burnap et al., 2015). It has been argued that the Trichodesmium colony as a whole would benefit from a tight nutrient coupling system wherein host-exuded organics may be catabolized relatively rapidly by a metabolically diverse consortium, thereby in part relieving C-limitation in addition to reducing local O2 concentrations/inhibition of N2 fixation (Paerl et al., 1989; O’Neil and Roman, 1992; Paerl and Pinckney, 1996). Here we present two examples where A. macleodii possesses, and was found to be expressing, the genetic machinery to degrade specific C compounds produced by Trichodesmium.

Methanol is an important small C compound in the global ocean primarily because of its role in atmospheric ozone production (Heikes, 2002). Recently, a wide phylogenetic array of phytoplankton have been shown to produce methanol in significant amounts as a by-product (up to μM levels for Trichodesmium; Mincer and Aicher, 2016). Correspondingly, there is genetic evidence that A. macleodii may be involved in methanol catabolism as our representative genome possesses two distinct genes identified as pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent alcohol dehydrogenases (enzymes that catalyze methanol/ethanol oxidation, and are often indicative of facultative methylotrophy; Chistoserdova, 2011), as well as the pyrroloquinoline quinone biosynthesis pathway (all found to be actively transcribed, Supplementary Table S5). In keeping with these genomic observations, the three closely related A. macleodii isolates presented in Figure 1 were isolated in media containing methanol as the sole C source. Given A. macleodii’s consistent association with Trichodesmium, and its ability to catabolize methanol, it is possible this is one mechanism by which it is aiding its host through rapid C cycling and O2 drawdown.

DMSP is an organosulfur compound produced and exuded by many phytoplankton and is a major intercellular metabolite (Stefels et al., 2007; Durham et al., 2015) that has been hypothesized to serve as an inter-trophic level signaling molecule. It is known to be both a strong chemoattractant (Seymour, 2010) and to induce the upregulation of AHLs (Johnson et al., 2016), although the full scope of its cellular function is not yet fully understood (Yoch, 2002). This compound is rapidly cycled by heterotrophic bacterioplankton, supplying up to 13% of bacterial C and up to 100% of bacterial sulfur demand (Kiene and Linn, 2000). Heterotrophs degrade DMSP via two enzymatically mediated pathways: a cleavage pathway (dddP) that provides a labile C source and produces DMS, an environmentally relevant trace gas (Simo, 2001), as a by-product; and a demethylation pathway (dmdA) that provides both C and reduced sulfur, foregoing DMS (Curson et al., 2011). To date, Trichodesmium is the only open ocean cyanobacteria that has been shown to produce significant intracellular concentrations of DMSP (Bucciarelli et al., 2013); a function that we confirmed in both the long-term Trichodesmium CO2 manipulation experiment and in T. erythraeum IMS101 grown under replete and P and Fe limitation (Supplementary Figure S4). Our A. macleodii bin has the genetic potential to both demethylate DMSP (beginning with dmdA; Supplementary Table S5) and cleave DMSP (dddP; Supplementary Table S5), with both found to be actively transcribed. It also has previously been demonstrated that some strains of A. macleodii (with 16S sequences 100% identical to those from the current study) can grow with DMSP as a sole C source (Raina et al., 2009). Although further investigation is needed to follow-up on this genetic potential between these co-occurring organisms, this is the first indication that DMSP may be actively cycled between a cyanobacterial host and its associated community. This suggests that in addition to associated community members potentially aiding their host through rapid C cycling within the colony, the use of DMSP as a signaling molecule for heterotrophs to alter their metabolic function toward a ‘cooperative lifestyle’ (Johnson et al., 2016) may also be occurring in our system.

Detoxification of ROS

When first presenting the BQH, Morris et al. postulated a mutualistic relationship between the picocyanobacterium Prochlorococcus and ‘helper’ bacteria. This mutualism was based on the seemingly paradoxical lack of a catalase-peroxidase gene (katG), or any heme-based catalases or peroxidases, to aid the O2-evolving cyanobacterium in detoxifying ROS (Morris et al., 2008, 2012). IMS101, the only finished Trichodesmium genome, is annotated in IMG (Markowitz et al., 2009) as possessing a catalase peroxidase. However, upon closer inspection this gene was identified as a pseudogene that has undergone substantial gene decay (Fawal et al., 2013). As annotated by IMG, it remains as only three gene fragments (Tery_1759, 1760 and 1761) interspersed with start and stop codons, and totals <700-bp relative to the ~2100-bp functional gene. Furthermore, katG genes have been frequently transferred between organisms (Bernroitner et al., 2009), and it appears as though Trichodesmium’s former katG was horizontally acquired before its pseudogenization as phylogenetic analysis of the PeroxiBase pseudogene sequence places it deep within the Bacteroidetes clade, distinct from other Cyanobacteria (Supplementary Figure S5). In accordance with this apparent history, a recent survey found that horizontally transferred genes were twice as likely as those vertically transmitted to become pseudogenized (Liu et al., 2004).

Consistent with the BQH ‘helper’ role, our A. macleodii possesses a katG found to be transcriptionally active (Supplementary Table S5), and the species is known to produce catalase peroxidase (Morris et al., 2011). In fact, a strain of A. macleodii was the first ‘helper’ bacteria described to assist the growth of Prochlorococcus (Morris et al., 2008) as a result of this activity. This suggests that A. macleodii may be aiding in the detoxification of ROS within Trichodesmium consortia in a similar manner. ROS toxicity is particularly problematic for photoautotrophs exposed to intense irradiance, and as Trichodesmium frequently forms large surface blooms, ROS detoxification could thus be an important service provided by A. macleodii for its cyanobacterial host.

The Alteromonas genus: functional distribution and association with photoautotrophs

There are currently 16 Alteromonas ‘finished’ genomes available through IMG (Markowitz et al., 2009) (accessed July 2016), many with differences regarding the aforementioned functions identified in our Trichodesmium-derived A. macleodii bin. For instance, only 2 of the 16 also contain a gene cluster for siderophore production, only 3 possess an mdh2 gene (implicated in methylotrophy; Keltjens et al., 2014), and 7 are predicted to produce AHLs (Supplementary Table S7). In contrast, similarities can be seen across the genus in the possession of genes related to DMSP degradation, APase activity, and the apparent facultative usage of vitamin B12 (Supplementary Table S7).

Recently, the genome of an A. macleodii isolated from a Prochlorococcus culture has been constructed (Biller et al., 2015). In searching this genome for the above-discussed genetic capabilities, this strain contains all of those found within our bin, except, interestingly, the potential to produce AHLs (Supplementary Table S7). This may reflect that the density of organisms associated with the unicellular Prochlorococcus is much lower than in the relatively enriched Trichodesmium colony environment, which may render quorum sensing ineffective. Whether there are properties of some A. macleodii that make them more prone to being associated with photoautotrophs, as opposed to particles, warrants deeper investigation.

Conclusion

Here we have presented molecular evidence that Trichodesmium may be consistently associated with A. macleodii in both laboratory-maintained enrichments and in situ (at the marker-gene and genome level). These data do not, however, allow us to address the exclusivity or promiscuity with regard to A. macleodii. Ultimately any organismal associations are going to be functionally and characteristically driven, rather than taxonomically or even phylogenomically. As such, it is possible similar heterotrophic strains may be commonly found co-occurring with various photoautotrophs (as they tend to exhibit comparable qualities), whereas Trichodesmium spp. may only exist in association with A. macleodii; importantly, this would not lessen the potential import of A. macleodii’s impact on Trichodesmium’s physiology.

The unique lifestyle of Trichodesmium and its biogeochemical significance make its colonial infrastructure an ideal and necessary regime to be viewed in the light of co-evolutionary processes such as those laid out by the BQH. In addition to showing that Trichodesmium may consistently harbor A. macleodii, we have further presented genetic and experimental evidence that generates several hypotheses regarding potential interactions between these organisms that may ultimately be contributing to the maintenance of this association (Figure 3). Although direct experimental observation of these putative mutualistic interactions is not a trivial task (as there are no axenic cultures of Trichodesmium), this work opens the door to further investigations of this relationship.

Schematic of the discussed potential interactions between Trichodesmium and A. macleodii. Beige box, Trichodesmium; Purple boxes, A. macleodii cells; AA, amino acids; APases, alkaline phosphatase; DMS, dimethylsulfide; KatG, catalase-peroxidase; red ellipses, siderophores. (Colony image courtesy of WHOI).

Photoautotroph–heterotroph associations represent complex systems of interorganismal interactions and A. macleodii is only one of many organisms thriving within Trichodesmium colonies. While this work provides a foundation and path toward targeted investigations of what may be a keystone organism within these consortia, many interactions likely exist between this host and its other epibionts, as well as solely between the various associated organisms. Ultimately these intricate networks of organismal interconnectivity have direct impacts on the physiology of Trichodesmium, and therefore on fluxes of biologically and climatically relevant elements such as C, N, P, Fe and S in the open ocean. Unraveling these networks is integral to our understanding of not only Trichodesmium’s productivity and evolution, but also to our emerging picture of ocean biogeochemistry.

References

Alneberg J, Bjarnason BSS, de Bruijn I, Schirmer M, Quick J, Ijaz UZ et al. (2014). Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat Meth 11: 1144–1146.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ . (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410.

Amin SA, Green DH, Hart MC, Küpper FC, Sunda WG, Carrano CJ . (2009). Photolysis of iron-siderophore chelates promotes bacterial-algal mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17071–17076.

Amin SA, Parker MSM, Armbrust EV . (2012). Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbio Mol Bio R 76: 667–684.

Augustus AM, Spicer LD . (2011). The MetJ regulon in Gammaproteobacteria determined by comparative genomics methods. BMC Gen 12: 558.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comp Biol 19: 455–477.

Barbeau K, Rue EL, Bruland KW, Butler A . (2001). Photochemical cycling of iron in the surface ocean mediated by microbial iron(III)-binding ligands. Nature 413: 409–413.

Beliaev AS, Romine MF, Serres M, Bernstein HC, Linggi BE, Markillie L et al. (2014). Inference of interactions in cyanobacterial–heterotrophic co-cultures via transcriptome sequencing. ISME J 8: 2243–2255.

Bernroitner M, Zamocky M, Furtmu PG, Furtmüller PG, Peschek GA, Obinger C . (2009). Occurrence, phylogeny, structure, and function of catalases and peroxidases in cyanobacteria. J Exp Bot 60: 423–440.

Bertrand EM, Allen AE . (2012). Influence of vitamin B auxotrophy on nitrogen metabolism in eukaryotic phytoplankton. Front Microbio 3: 1–16.

Bertrand EM, McCrow JP, Moustafa A, Zheng H, McQuaid JB, Delmont TO et al. (2015). Phytoplankton-bacterial interactions mediate micronutrient colimitation at the coastal Antarctic sea ice edge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 9938–9943.

Biller SJ, Coe A, Chisholm SW, Foun- BM . (2015). Draft genome sequence of Alteromonas macleodii strain MIT1002, isolated from an enrichment culture of a marine cyanobacterium. Genome Announc 3: 3–4.

Bonnet S, Webb Ea, Panzeca C, Karl DM, Capone DG, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA . (2010). Vitamin B12 excretion by cultures of the marine cyanobacteria Crocosphaera and Synechococcus. Limnol Oceanogr 55: 1959–1964.

Borstad GA . (1978) Some Aspects of the Occurrence and Biology of Trichodesmium Near Barbados. McGill University: Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Bucciarelli E, Ridame C, Sunda WG, Dimier-Hugueney C, Cheize M, Belviso S et al. (2013). Increased intracellular concentrations of DMSP and DMSO in iron-limited oceanic phytoplankton Thalassiosira oceanica and Trichodesmium erythraeum. Limnol Oceanogr 58: 1667–1679.

Burnap R, Hagemann M, Kaplan A . (2015). Regulation of CO2 concentrating mechanism in Cyanobacteria. Life 5: 348–371.

Carpenter EJ, Price CC . (1976). Marine oscillatoria (Trichodesmium: explanation for aerobic nitrogen fixation without heterocysts. Science 191: 1278–1280.

Case RJ, Labbate M, Kjelleberg S . (2008). AHL-driven quorum-sensing circuits: their frequency and function among the Proteobacteria. ISME J 2: 345–349.

Chappell PD, Moffett JW, Hynes AM, Webb EA . (2012). Molecular evidence of iron limitation and availability in the global diazotroph Trichodesmium. ISME J 6: 1728–1739.

Chappell PD, Webb EA . (2010). A molecular assessment of the iron stress response in the two phylogenetic clades of Trichodesmium. Environ Microbiol 12: 13–27.

Chen YB, Zehr JP, Mellon M . (1996). Growth and nitrogen fixation of the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. IMS 101 in defined media: evidence for a circadian rhythm. J Phycol 32: 916–923.

Chistoserdova L . (2011). Modularity of methylotrophy, revisited. Environ Microbiol 13: 2603–2622.

Croft MT, Lawrence AD, Raux-deery E, Warren MJ, Smith AG . (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438: 90–93.

Curson ARJ, Todd JD, Sullivan MJ, Johnston AWB . (2011). Catabolism of dimethylsulphoniopropionate: microorganisms, enzymes and genes. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 849–859.

Dupont CL, McCrow JP, Valas R, Moustafa A, Walworth N, Goodenough U et al. (2015). Genomes and gene expression across light and productivity gradients in eastern subtropical Pacific microbial communities. ISME J 9: 1076–1092.

Durham BP, Sharma S, Luo H, Smith CB, Amin SA, Bender SJ et al. (2015). Cryptic carbon and sulfur cycling between surface ocean plankton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 453–457.

Edgar RC . (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinf 5: 113.

Eren AM, Morrison HG, Lescault PJ, Reveillaud J, Vineis JH, Sogin ML . (2014). Minimum entropy decomposition: unsupervised oligotyping for sensitive partitioning of high-throughput marker gene sequences. ISME J 9: 968–979.

Eren AM, Esen ÖC, Quince C, Vineis JH, Morrison HG, Sogin ML et al. (2015). Anvi’o: an advanced analysis and visualization platform for ‘omics data. PeerJ 3: e1319.

Eren AM, Maignien L, Sul WJ, Murphy LG, Grim SL, Morrison HG et al. (2013). Oligotyping: differentiating between closely related microbial taxa using 16S rRNA gene data. Methods Ecol Evol 4: 1111–1119.

Fawal N, Li Q, Savelli B, Brette M, Passaia G, Fabre M et al. (2013). PeroxiBase: a database for large-scale evolutionary analysis of peroxidases. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 441–444.

Fay P . (1992). Oxygen relations of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria. Microbiol Rev 56: 340–373.

Fisher MM, Wilcox LW, Graham LE . (1998). Molecular characterization of epiphytic bacterial communities on charophycean green algae. Microb Ecol 64: 4384–4389.

Guannel ML, Horner-Devine MC, Rocap G . (2011). Bacterial community composition differs with species and toxigenicity of the diatom Pseudo-nitzschia. Aquat Microb Ecol 64: 117–133.

Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G . (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. BMC Bioinform (Oxford, England) 29: 1072–1075.

Heikes BG . (2002). Atmospheric methanol budget and ocean implication. Global Biogeochem Cycles 16: 1–13.

Hein M, Sand-Jensen K . (1997). CO2 increases oceanic primary production. Nature 388: 526–527.

Hewson I, Poretsky RS, Dyhrman ST, Zielinski B, White AE, Tripp HJ et al. (2009). Microbial community gene expression within colonies of the diazotroph, Trichodesmium, from the Southwest Pacific Ocean. ISME J 3: 1286–1300.

Hmelo LR, Van Mooy BAS, Mincer TJ . (2012). Characterization of bacterial epibionts on the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Aquat Microb Ecol 67: 1–14.

Hutchins DA, Walworth NG, Webb EA, Saito MA, Moran D, McIlvin MR et al. (2015). Irreversibly increased nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium experimentally adapted to elevated carbon dioxide. Nat Comm 6: 8155.

Hynes AM, Chappell PD, Dyhrman ST, Doney SC, Webb EA . (2009). Cross-basin comparison of phosphorus stress and nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 1438–1448.

Johnson WM, Soule MCK, Kujawinski EB . (2016). Evidence for quorum sensing and differential metabolite production by a marine bacterium in response to DMSP. ISME J 10: 1–13.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S et al. (2012). Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. BMC Bioinform 28: 1647–1649.

Keltjens JT, Pol A, Reimann J, Op Den Camp HJM . (2014). PQQ-dependent methanol dehydrogenases: rare-earth elements make a difference. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98: 6163–6183.

Kiene RP, Linn LJ . (2000). Distribution and turnover of dissolved DMSP and its relationship with bacterial production and dimethylsulfide in the Gulf of Mexico. Limnol Oceanogr 45: 849–861.

Kiene RP, Service SK . (1991). Decomposition of dissolved DMSP and DMS in estuarine waters: dependence on temperature and substrate concentration. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 76: 1–11.

Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD . (2013). Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 5112–5120.

Kranzler C, Lis H, Shaked Y, Keren N . (2011). The role of reduction in iron uptake processes in a unicellular, planktonic cyanobacterium. Environ Microbiol 13: 2990–2999.

Kupper FC, Carrano CJ, Kuhn JU, Butler A . (2006). Photoreactivity of iron(III)-aerobactin: photoproduct structure and iron(III) coordination. Inorganic Chem 45: 6028–6033.

Lachnit T, Blumel M, Imhoff JF, Wahl M . (2009). Specific epibacterial communities on macroalgae: phylogeny matters more than habitat. Aquat Biol 5: 181–186.

Lachnit T, Meske D, Wahl M, Harder T, Schmitz R . (2011). Epibacterial community patterns on marine macroalgae are host-specific but temporally variable. Environ Microbiol 13: 655–665.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL . (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359.

Lee MD, Walworth NG, Sylvan JB, Edwards KJ, Orcutt BN . (2015). Microbial communities on seafloor basalts at Dorado Outcrop reflect level of alteration and highlight global lithic clades. Front Microbiol 6 : 1–20.

Liu Y, Harrison PM, Kunin V, Gerstein M . (2004). Comprehensive analysis of pseudogenes in prokaryotes: widespread gene decay and failure of putative horizontally transferred genes. Genome Biol 5: R64.

Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC . (2009). IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 25: 2271–2278.

Mclellan SL, Newton RJ, Vandewalle JL, Shanks OC, Huse SM, Eren AM et al. (2013). Sewage reflects the distribution of human faecal Lachnospiraceae. Environ Microbiol 15: 2213–2227.

Mincer TJ, Aicher AC . (2016). Methanol production by a broad phylogenetic array of marine phytoplankton. PLoS One 11: 1–17.

Morris JJ . (2015). Black Queen evolution: the role of leakiness in structuring microbial communities. Trends Genet 31: 475–482.

Morris JJ, Johnson ZI, Szul MJ, Keller M, Zinser ER . (2011). Dependence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus on hydrogen peroxide scavenging microbes for growth at the ocean’s surface. PLoS One 6: e16805.

Morris JJ, Kirkegaard R, Szul MJ, Johnson ZI, Zinser ER . (2008). Facilitation of robust growth of Prochlorococcus colonies and dilute liquid cultures by 'helper' heterotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 4530–4534.

Morris J, Lenski RE, Zinser ER . (2012). The Black Queen hypothesis: evolution of dependencies through adaptive gene loss. Mol Bio 3: e00036–12.

Mulholland MR, Bernhardt PW, Heil CA, Bronk DA, Neil JMO . (2006). Nitrogen fixation and release of fixed nitrogen by Trichodesmium spp. in the Gulf of Mexico. Limnol Oceanogr 51: 1762–1776.

Nausch M . (1996). Microbial activities on Trichodesmium colonies. Mar Ecol Prog Series 141: 173–181.

O’Neil JM, Roman MR . (1992). Grazers and associated organisms of Trichodesmium. Marine Pelagic Cyanobacteria Trichodesmium Other Diazotrophs 362: 61–73.

Paerl H, Bebout B, Prufert L . (1989). Bacterial associations with marine Oscillatoria sp. (Trichodesmium sp.) populations: ecophysiological implications. J Phyc 25: 773–784.

Paerl HW, Bebout BM . (1988). Direct measurement of O2-depleted microzones in marine Oscillatoria): relation to N2-fixation. Science Wash 241: 442–445.

Paerl HW, Kellar PE . (1978). Significance of bacterial-Anabaena associations with respect to N2 fixation in freshwater. J Phyc 14: 254–260.

Paerl HW, Pinckney JL . (1996). A mini-review of microbial consortia: their roles in aquatic production and biogeochemical cycling. Microb Ecol 31: 225–247.

Parada A, Needham DM, Fuhrman JA . (2015). Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time-series and global field samples. Environ Microbiol 18: 1403–1414.

Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin FYL . (2012). IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28: 1420–1428.

Prufert-Bebout L, Paerl HW, Lassen C . (1993). Growth, nitrogen fixation, and spectral attenuation in cultivated Trichodesmium species. Appl Envir Microbiol 59: 1367–1375.

Raina JB, Tapiolas D, Willis BL, Bourne DG . (2009). Coral-associated bacteria and their role in the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur. Appl Envir Microbiol 75: 3492–3501.

Roe KL, Barbeau KA . (2014). Uptake mechanisms for inorganic iron and ferric citrate in Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101. Metallomics 6: 2042–2051.

Rouco M, Haley ST, Dyhrman ST . (2016). Microbial diversity within the Trichodesmium holobiont. Environ Microbiol 18: 5151–5160.

Sachs JL, Hollowell AC . (2012). The origins of cooperative bacterial communities. Mol Bio 3: e00099–12-e00099-12.

Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA, Gómez-Consarnau L, Suffridge C, Webb EA . (2014). The role of B vitamins in marine biogeochemistry. Ann Rev Mar Sci 6: 339–367.

Sapp M, Schwaderer AS, Wiltshire KH, Hoppe HG, Gerdts G, Wichels A . (2007). Species-specific bacterial communities in the phycosphere of microalgae? Microbial Ecol 53: 683–699.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. App Environ Microbiol 75: 7537–7541.

Schwyn B, Neilands JB . (1987). ‘Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem 160: 47–56.

Seymour JR . (2010). Chemoattraction to dimethylsulfoniopropionate throughout the marine microbial food web. Science 329 : 342–346.

Simo R . (2001). Production of atmospheric sulfur by oceanic plankton: biogeochemical, ecological and evolutionary links. Trends Ecol Evol 16: 287–294.

Sison-mangus MP, Jiang S, Tran KN, Kudela RM . (2014). Host-specific adaptation governs the interaction of the marine diatom, Pseudo-nitzschia and their microbiota. ISME J 8: 63–76.

Stefels J, Steinke M, Turner S, Malin G, Belviso S . (2007). Environmental constraints on the production and removal of the climatically active gas dimethylsulphide (DMS) and implications for ecosystem modelling. Biogeochem 83: 245–275.

Stevenson BS, Waterbury JB . (2006). Isolation and identification of an epibiotic bacterium associated with heterocystous Anabaena cells. Biol Bull 210: 73–77.

Stothard P . (2000). The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques 6: 1102–1104.

Van Mooy BAS, Hmelo LR, Sofen LE, Campagna SR, May AL, Dyhrman ST et al. (2012). Quorum sensing control of phosphorus acquisition in Trichodesmium consortia. ISME J 6: 422–429.

Vraspir JM, Butler A . (2009). Chemistry of marine ligands and siderophores. Ann Rev Mar Sci 1: 43–63.

Walworth N, Pfreundt U, Nelson WC, Mincer T, Heidelberg JF, Fu F et al. (2015). Trichodesmium genome maintains abundant, widespread noncoding DNA in situ, despite oligotrophic lifestyle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 4251–4256.

Waterbury JB . (2006). The Cyanobacteria - isolation, purification and indentification. Prok 4: 1053–1073.

Webb EA, Jakuba RW, Moffett JW, Dyhrman ST . (2007). Molecular assessment of phosphorus and iron physiology in Trichodesmium populations from the western Central and western South Atlantic. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 2221–2232.

Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R et al. (2015). AntiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 43: W237–W243.

Yoch DC . (2002). Dimethylsulfoniopropionate: its sources, role in the marine food web, and biological degradation to dimethylsulfide. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 5804–5815.

Zehr JP . (1995). Nitrogen fixation in the sea: why only Trichodesmium? Molecular Ecol Aquat Micr G38: 335–364.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gustavo Ramirez for insightful discussion and assistance in editing the manuscript through various draft stages. Funding was provided by US National Science Foundation grants BO-OCE 1260490 to DAH, EAW and F-XF, a Rose Hills Foundation grant to NML and EM, and CHE-OCE 1131415 to TJM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, M., Walworth, N., McParland, E. et al. The Trichodesmium consortium: conserved heterotrophic co-occurrence and genomic signatures of potential interactions. ISME J 11, 1813–1824 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.49

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.49

This article is cited by

-

Nutrient availability regulates the microbial biomass structure in marine oligotrophic waters

Hydrobiologia (2024)

-

Comparative genomic analysis of Flavobacteriaceae: insights into carbohydrate metabolism, gliding motility and secondary metabolite biosynthesis

BMC Genomics (2020)

-

Distinct nitrogen cycling and steep chemical gradients in Trichodesmium colonies

The ISME Journal (2020)

-

Genomic, metabolic and phenotypic variability shapes ecological differentiation and intraspecies interactions of Alteromonas macleodii

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Colonies of marine cyanobacteria Trichodesmium interact with associated bacteria to acquire iron from dust

Communications Biology (2019)