Abstract

Rising sea surface temperature is the main cause of global coral reef decline. Abnormally high temperatures trigger the breakdown of the symbiotic association between corals and their photosynthetic symbionts in the genus Symbiodinium. Higher genetic variation resulting from shorter generation times has previously been proposed to provide increased adaptability to Symbiodinium compared to the host. Retrotransposition is a significant source of genetic variation in eukaryotes and some transposable elements are specifically expressed under adverse environmental conditions. We present transcriptomic and phylogenetic evidence for the existence of heat stress-activated Ty1-copia-type LTR retrotransposons in the coral symbiont Symbiodinium microadriaticum. Genome-wide analyses of emergence patterns of these elements further indicate recent expansion events in the genome of S. microadriaticum. Our findings suggest that acute temperature increases can activate specific retrotransposons in the Symbiodinium genome with potential impacts on the rate of retrotransposition and the generation of genetic variation under heat stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Coral reefs are notable for being one of the world’s most productive and diverse ecosystems despite flourishing in highly oligotrophic environments (de Goeij et al., 2013). This paradox exists because of the endosymbiotic relationship between corals and unicellular algae of the genus Symbiodinium, whereby corals provide nutrients and shelter to the algae in exchange for energy in the form of photosynthetically fixed carbon (Muscatine and Porter, 1977). In the past few decades, most coral ecosystems around the world have been gradually declining, a process that has been accelerated by the warming of the oceans (Ainsworth et al., 2016). The coral Symbiodinium symbiosis is notably sensitive to increases in seawater temperature, which can lead to widespread expulsion of the symbiont and eventual starvation of the coral hosts if the symbiotic relationship is not restored (Hoegh-Guldberg and Smith, 1989). However, the presence of thermotolerant corals, such as those in the Red Sea (Fine et al., 2013), strongly suggests that there is room for adaptation to higher ocean temperatures. One component that determines coral thermotolerance is the presence of Symbiodinium strains that are more resistant to heat stress (Howells et al., 2012). Given the shorter generation times of Symbiodinium relative to their coral hosts, it has been speculated that the higher rate at which genetic variation increases in Symbiodinium could play a major role in the evolution of coral–algal symbiosis with greater thermotolerance (Csaszar et al., 2010; van Oppen et al., 2017).

One way in which rapid and environmentally triggered genomic variation could be generated is via retrotransposons, whose capability to replicate independently of the host genome makes them particularly interesting as one of the causal agents of natural insertional mutagenesis (Kazazian, 2004). While most retrotransposons are transcriptionally silenced by the host genome, several lines of evidence suggest that these genetic elements can be activated under certain stress conditions such as wounding (Takeda et al., 1998) or UV irradiation (Ramallo et al., 2008).

A specific class of retrotransposons, defined by the presence of flanking long terminal repeats (LTR), is notable for being transcriptionally activated by a range of stress conditions in fungi (Anaya and Roncero, 1996), metazoans (Faure et al., 1996) and higher plants (Ito et al., 2011). An example of this is ONSEN, a Ty1-copia-type LTR retrotransposon in Arabidopsis thaliana that was shown to be activated by elevated temperatures and capable of generating A. thaliana lines resistant to abscisic acid, thereby linking heat stress with the generation of novel phenotypes via retrotransposon-mediated mutagenesis (Ito et al., 2011, 2016).

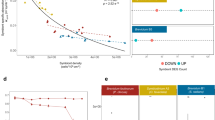

We have identified four sequences in the Symbiodinium microadriaticum genome (Aranda et al., 2016) as putative Ty1-copia class LTR retrotransposons using previously published transcriptomic data (Liew et al., 2017), henceforth referred to as S. m icroadriaticum T y1- C opia- L ike (SmTCL) 1, 2, 3 and 4. The first two were identified as being the two most upregulated genes in response to 36 °C temperature stress (Supplementary Table S1) in the assembled transcriptome. In addition, we identified two further heat stress-activated SmTCLs by conducting an independent differential expression analysis on a set of genome-curated sequences that were pre-identified as Ty1-copia sequences (Supplementary Table S2).

To confirm that the overexpression of these sequences was indeed a direct consequence of the heat stress treatment, we repeated the RNA extraction experiment twice and validated the differential expression of SmTCL1, 2 and 3 using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) (Figure 1a). All three SmTCLs were significantly upregulated in heat-stressed samples. In addition, we also tested the expression of Fox-1 and CYPLIIA8, which were the two most downregulated transcripts in our RNA-Seq data set (Supplementary Table S1).

Evidence for putative heat stress-activated Ty1-copia-like retrotransposons. (a) qPCR expression analysis of selected genes under heat stress. SmTCL, S. microadriaticum Ty-copia-like; Fox-1, RNA-binding protein fox-1 homolog; CYPLIIA8, Cytochrome P450. Error bars show the standard error of the means. **one-tailed t-test P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (b) Domain arrangements of various LTR retroelements. LTR, long terminal repeats; PBS, primer binding site; gag, group-specific antigen; pol, pol polyprotein; PR, protease; INT, integrase; RT, reverse transcriptase; RH, ribonuclease H; PPT, polypurine tract; env, envelope protein. (c) Maximum likelihood phylogeny of 32 reverse transcriptase or RNA-dependent RNA polymerase amino-acid domains of various retrotransposons and viruses. Dotted lines indicate polyphyletic groupings and the scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site. Node support values indicate bootstrap support.

Analysis of the genetic structure showed that all four SmTCLs possess a reverse transcriptase (RT) domain, an integrase domain upstream of said RT domain, a RNase H domain and are flanked by LTRs (Figure 1b). The position of the integrase domain plays a key role in the classification of the two major classes of LTR retrotransposons: Ty1-copia and Ty3-gypsy. The domain arrangement of Ty3-gypsy is very similar to that of retroviruses (Figure 1b), with the integrase domain being downstream of the reverse transcriptase domain. We also built a phylogenetic tree (Figure 1c) using the aligned amino-acid sequences of 28 model reverse transcriptases (Supplementary Figure S1) from a diverse variety of retroelements (Xiong and Eickbush, 1990) in order to classify the SmTCLs. We found that all SmTCLs clustered together with the Ty1-copia family of retrotransposons. To our knowledge, this is the first reported example of heat-activated retrotransposons in S. microadriaticum in particular, and dinoflagellates in general.

We determined the prevalence of SmTCL RT isoforms in the genome using genome-wide BLAST analysis and identified 343 RT sequences, which were classified as Ty1-copia-like sequences based on phylogenetic analysis relative to a retrovirus and Ty3-gypsy outgroup (Figure 2a). The SmTCLs grouped separately, indicating that these sequences diverged some time ago.

Genome-wide analyses of copia-like elements. (a) Maximum likelihood phylogeny of 365 reverse transcriptase amino-acid sequences curated in silico from the S. microadriaticum genome. Green lines indicate known Ty1-copia-type sequences, orange lines indicate SmTCL1-4, pink lines indicate retrovirus, caulimovirus and Ty3-gypsy-like outgroup sequences as seen in Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure S1, black lines indicate Ty1-copia-like sequences. Sequences considered to form the SmTCL subclades are highlighted in yellow. Bootstrap values below 70 were removed from the phylogeny. Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site. (b) Jukes–Cantor distribution of selected retrotransposon families in the S. microadriaticum genome. Insert plot shows the distribution of retrotransposons within the 0–0.01 Jukes–Cantor distance fraction, at bin sizes of 0.001. SmTCL (purple line) shows the genome coverage of sequences associated with the heat responsive elements SmTCL1-4. A sequence with 50% of its nucleotide positions different from its consensus sequence would have a Jukes–Cantor distance of 0.824 according to the equation,  , where p is the proportion of sites with different nucleotides and d is the Jukes–Cantor distance.

, where p is the proportion of sites with different nucleotides and d is the Jukes–Cantor distance.

A genome-wide analysis of the Jukes–Cantor distribution of LTR retrotransposons (Chapman et al., 2010) in the Symbiodinium genome indicates that copia-like sequences have had a recent increase in copy numbers, as evidenced by a large number of elements showing almost no sequence divergence (0–0.01 Jukes–Cantor distance) (Figure 2b). In terms of genome coverage, the plurality of copia sequences are considered near-identical to their consensus sequences indicating that they have not had the time to acquire nucleotide changes. Interestingly, we found that the heat responsive elements SmTCLs1–4 constituted ~26% of the genome coverage of the lowest divergence fraction (0–0.001 Jukes–Cantor distance), indicating that these elements expanded recently (Supplementary Table S3). For SmTCL3, for instance, we identified five near-identical full-length copies (>99.9% similarity over ~10 kb) as well as a 500 bp copy with the same LTRs (Supplementary Data S1).

In the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, expression of the Ty1-copia-like retrotransposons Blackbeard was found to be induced by nitrate starvation (Maumus et al., 2009). Different accessions of P. tricornutum were shown to possess different retrotransposition events that were distinguishable at the population level. Like Symbiodinium, P. tricornutum has not been directly observed to undergo sexual reproduction (Levin et al., 2016). Unlike Phaeodactylum, Symbiodinium has a haploid genome (Santos and Coffroth, 2003) and thus retrotransposition into a functional genomic region would likely have a stronger phenotypic effect. Retrotransposon-mediated stress-activated mutagenesis could thus be a mechanism to generate additional genetic variation under adverse conditions, where the cost of deleterious mutations is outweighed by the possibility of acquiring novel adaptations (Rey et al., 2016).

Our results do not provide evidence for new, heat stress-induced retrotransposition events, but they suggest that mutation rates for S. microadriaticum could increase substantially due to stress-mediated transcriptional activation of transposons, leading to a greater-than-expected increase in genetic variation under acute heat stress (Chakravarti et al., 2017). Further work investigating whether isolated, post-heat-stressed S. microadriaticum possess more LTR retrotransposon copy numbers compared to non-stressed control cultures would be the first step to establishing whether these new retrotransposition events are capable of generating new phenotypes from a clonal parental population. This would provide some indication whether it would be feasible to generate phenotypes with increased coral symbiosis resilience to heat stress via heat stress-induced ‘experimental evolution’ of S. microadriaticum strains (van Oppen et al., 2017). Additionally, in natura analyses comparing LTR retrotransposon copy numbers in Symbiodinium populations from sites differing in temperature fluctuations could provide further evidence for the ecological relevance of such a mechanism under natural conditions.

References

Ainsworth TD, Heron SF, Ortiz JC, Mumby PJ, Grech A, Ogawa D et al. (2016). Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 352: 338–342.

Anaya N, Roncero MIG . (1996). Stress-induced rearrangement of Fusarium retrotransposon sequences. Mol Gen Genet 253: 89–94.

Aranda M, Li Y, Liew YJ, Baumgarten S, Simakov O, Wilson MC et al. (2016). Genomes of coral dinoflagellate symbionts highlight evolutionary adaptations conducive to a symbiotic lifestyle. Sci Rep 6: 39734.

Chakravarti LJ, Beltran VH, van Oppen MJH . (2017). Rapid thermal adaptation in photosymbionts of reef-building corals. Glob Chang Biol,. (2017) 23: 4675–4688.

Chapman JA, Kirkness EF, Simakov O, Hampson SE, Mitros T, Weinmaier T et al. (2010). The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature 464: 592–596.

Csaszar NBM, Ralph PJ, Frankham R, Berkelmans R, van Oppen MJH . (2010). Estimating the potential for adaptation of corals to climate warming. PLoS One 5: e9751.

de Goeij JM, van Oevelen D, Vermeij MJ, Osinga R, Middelburg JJ, de Goeij AF et al. (2013). Surviving in a marine desert: the sponge loop retains resources within coral reefs. Science 342: 108–110.

Faure E, BestBelpomme M, Champion S . (1996). X-irradiation activates the Drosophila 1731 retrotransposon LTR and stimulates secretion of an extracellular factor that induces the 1731-LTR transcription in nonirradiated cells. J Biochem 120: 313–319.

Fine M, Gildor H, Genin A . (2013). A coral reef refuge in the Red Sea. Glob Change Biol 19: 3640–3647.

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Smith GJ . (1989). The effect of sudden changes in temperature, light and salinity on the population-density and export of zooxanthellae from the reef corals Stylophora pistillata Esper and Seriatopora hystrix Dana. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 129: 279–303.

Howells EJ, Beltran VH, Larsen NW, Bay LK, Willis BL, van Oppen MJH . (2012). Coral thermal tolerance shaped by local adaptation of photosymbionts. Nat Clim Change 2: 116–120.

Ito H, Gaubert H, Bucher E, Mirouze M, Vaillant I, Paszkowski J . (2011). An siRNA pathway prevents transgenerational retrotransposition in plants subjected to stress. Nature 472: 115–119.

Ito H, Kim JM, Matsunaga W, Saze H, Matsui A, Endo TA et al. (2016). A stress-activated transposon in Arabidopsis induces transgenerational abscisic acid insensitivity. Sci Rep 6: 23181.

Kazazian HH Jr . (2004). Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science 303: 1626–1632.

Levin RA, Beltran VH, Hill R, Kjelleberg S, McDougald D, Steinberg PD et al. (2016). Sex, scavengers, and chaperones: transcriptome secrets of divergent Symbiodinium thermal tolerances. Mol Biol Evol 33: 2201–2215.

Liew YJ, Li Y, Baumgarten S, Voolstra CR, Aranda M . (2017). Condition-specific RNA editing in the coral symbiont Symbiodinium microadriaticum. PLoS Genet 13: e1006619.

Maumus F, Allen AE, Mhiri C, Hu HH, Jabbari K, Vardi A et al. (2009). Potential impact of stress activated retrotransposons on genome evolution in a marine diatom. BMC Genomics 10: 624.

Muscatine L, Porter JW . (1977). Reef corals - mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. BioScience 27: 454–460.

Ramallo E, Kalendar R, Schulman AH, Martinez-Izquierdo JA . (2008). Reme1, a Copia retrotransposon in melon, is transcriptionally induced by UV light. Plant Mol Biol 66: 137–150.

Rey O, Danchin E, Mirouze M, Loot C, Blanchet S . (2016). Adaptation to global change: a transposable element-epigenetics perspective. Trends Ecol Evol 31: 514–526.

Santos SR, Coffroth MA . (2003). Molecular genetic evidence that dinoflagellates belonging to the genus Symbiodinium freudenthal are haploid. Biol Bull 204: 10–20.

Takeda S, Sugimoto K, Otsuki H, Hirochika H . (1998). Transcriptional activation of the tobacco retrotransposon Tto1 by wounding and methyl jasmonate. Plant Mol Biol 36: 365–376.

van Oppen MJH, Gates RD, Blackall LL, Cantin N, Chakravarti LJ, Chan WY et al. (2017). Shifting paradigms in restoration of the world's coral reefs. Glob Chang Biol 23: 3437–3448.

Xiong Y, Eickbush TH . (1990). Origin and evolution of retroelements based upon their reverse transcriptase sequences. EMBO J 9: 3353–3362.

Acknowledgements

This publication is based on the work supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under Award No. URF/1/1705-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Cui, G., Wang, X. et al. Recent expansion of heat-activated retrotransposons in the coral symbiont Symbiodinium microadriaticum. ISME J 12, 639–643 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.179

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.179

This article is cited by

-

Regulation of cultured coral endosymbiont photophysiology by alternate heat stress protocols

Marine Biology (2024)

-

Nutritional control regulates symbiont proliferation and life history in coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis

BMC Biology (2022)

-

Genome-wide characterization of LTR retrotransposons in the non-model deep-sea annelid Lamellibrachia luymesi

BMC Genomics (2021)

-

A transposable element annotation pipeline and expression analysis reveal potentially active elements in the microalga Tisochrysis lutea

BMC Genomics (2018)

-

Recurrent acquisition of cytosine methyltransferases into eukaryotic retrotransposons

Nature Communications (2018)