Abstract

Host-microbe symbioses rely on the successful transmission or acquisition of symbionts in each new generation. Amphibians host a diverse cutaneous microbiota, and many of these symbionts appear to be mutualistic and may limit infection by the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which has caused global amphibian population declines and extinctions in recent decades. Using bar-coded 454 pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, we addressed the question of symbiont transmission by examining variation in amphibian skin microbiota across species and sites and in direct relation to environmental microbes. Although acquisition of environmental microbes occurs in some host-symbiont systems, this has not been extensively examined in free-living vertebrate-microbe symbioses. Juvenile bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana), adult red-spotted newts (Notophthalmus viridescens), pond water and pond substrate were sampled at a single pond to examine host-specificity and potential environmental transmission of microbiota. To assess population level variation in skin microbiota, adult newts from two additional sites were also sampled. Cohabiting bullfrogs and newts had distinct microbial communities, as did newts across the three sites. The microbial communities of amphibians and the environment were distinct; there was very little overlap in the amphibians’ core microbes and the most abundant environmental microbes, and the relative abundances of OTUs that were shared by amphibians and the environment were inversely related. These results suggest that, in a host species-specific manner, amphibian skin may select for microbes that are generally in low abundance in the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All animals are host to symbiotic micro-organisms that constitute their natural microbiota. As a result of these ancient, intimate associations, animals may rely on microbes for many critical life processes, such as digestion and energy acquisition (Wenzel et al., 2002; Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Rosenberg et al., 2007), circadian rhythm control (Heath-Heckman et al., 2013) and disease resistance (Dethlefsen et al., 2007; Rosenberg et al., 2007; Kaltenpoth and Engl, 2013). Advances in culture-independent molecular techniques, including next-generation sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, have greatly expanded our ability to characterize these often complex microbial communities and can provide key insights into the function of these symbiotic microbes, as well as to their maintenance in populations across generations.

Long-term host-microbe symbioses rely on the successful transmission or acquisition of symbionts in each new generation. In some systems, this may predominantly occur via vertical transmission from parent to offspring. Many insect-microbe symbioses are maintained by vertical transmission (Hosokawa et al., 2007; Damiani et al., 2008; Lauzon et al., 2009). However, in other systems, symbionts may predominantly be obtained from the environment in each new generation. This appears to be the case in the squid-Vibrio (Nyholm and McFall-Ngai, 2004), legume-Rhizobium (Jones et al., 2007) and stinkbug-Burkholderia (Kikuchi et al., 2007) symbioses. There is great variation in symbiont transmission modes among plants and animals, however, with some hosts using a combination of environmental acquisition and vertical transmission of symbiotic microbes (Bright and Bulgheresi, 2010). Understanding the route of transmission is important, as it influences evolutionary dynamics in the system (Ewald, 1987; Bright and Bulgheresi, 2010). For example, symbionts that are strictly transmitted vertically often exhibit reduced genome size as a result of gene loss and lack of horizontal gene transfer (Moran, 2003; Sachs et al., 2011a, 2011b). Genome reduction can affect the ability of these symbionts to evolve or repair degraded genes, which can limit the functioning of the symbionts and thus the evolution of the symbiosis (Sachs et al., 2011b). In contrast, symbionts that are transmitted via the environment often have large, expanded genomes (Sachs et al., 2011a). Conflicts of fitness interests exist between hosts and symbionts, even in obligate mutualisms, and transmission mode is thought to modulate these conflicts and thus influence evolutionary patterns (Sachs et al., 2011a). In addition to evolutionary implications of transmission, systems reliant on environmental transmission of symbionts may be more likely to be impacted by large-scale environmental change.

Work on transmission in free-living vertebrate-microbe symbioses suggests that factors such as habitat use and diet are likely important in determining the composition of the gut microbiota (for example, humans, non-human primates, other mammals, fish, iguanas; Ley et al., 2008a, 2008b; Nayak, 2010; Hong et al., 2011; Muegge et al., 2011; Amato et al., 2013). Several recent studies on fish suggest that the gut microbiota may not be a simple reflection of the microbes in their environment, but that selection for specific environmental microbes may be occurring (Roeselers et al., 2011; Sullam et al., 2012). Furthermore, by comparing the microbial communities of different species of larval amphibians cohabiting in single ponds and thus exposed to the same environmental inocula, the results of the study by McKenzie et al. (2011) suggest that host specificity, not pond environment, influences microbial community composition. However, few studies on free-living vertebrates have been able to directly assess the composition of the environmental microbes that individuals are exposed to in relation to their associated microbes using culture-independent methods.

Amphibian skin microbes provide a good model system for examining this question of transmission. In recent years, it has become clear that amphibians host a diverse array of cutaneous microbes (Culp et al., 2007; Lauer et al., 2007, 2008; McKenzie et al., 2011; Walke et al., 2011). Many of these microbial symbionts appear to be mutualistic and may have a role in resistance to the chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which has caused global amphibian population declines and extinctions in recent decades (Woodhams et al., 2007b; Harris et al., 2009a, 2009b; Becker and Harris, 2010; Lam et al., 2010), as well as to other potential amphibian pathogens (for example Banning et al., 2008). In the first next-generation sequencing study of these skin symbionts, McKenzie et al. (2011) demonstrated that these communities roughly parallel the complexities of the human skin microbiota, and that there are likely amphibian species-specific microbial assemblages, even across sites. There is also some evidence for different potential routes of transmission in amphibian microbe systems. Banning et al. (2008) and Walke et al. (2011) provide evidence that microbes may be vertically transmitted in two amphibian species that exhibit nest attendance behavior, while Muletz et al. (2012) experimentally demonstrated that it is possible to transfer probiotic bacteria from soil to salamanders. Using bar-coded 454 pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, we examined the bacterial community structure on the skin of two cohabiting amphibian species and the relationship of these bacterial communities with those of their pond environment. For one of these species, we surveyed two additional locations to examine population-level variation in skin microbiota. Lastly, we compared the bacteria associated with Virginia amphibians with those associated with Colorado amphibians sampled in McKenzie et al. (2011) to begin to synthesize our knowledge of amphibian skin microbiomes. The results we present have important implications for understanding host-microbe interactions in wildlife, including transmission of mutualistic symbionts.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

In a single pond at the University of Virginia’s Mountain Lake Biological Station (Giles County, VA, USA), we examined the bacterial community structure of juvenile bullfrogs, Rana catesbeiana (N=12), and cohabiting adult red-spotted newts, Notophthalmus viridescens (N=10), and how their communities relate to those of their pond environment (water, N=3; substrate, N=3). Although it is possible amphibians could acquire microbes from environmental sources other than pond water and pond substrate (for example, vegetation or forest surrounding the pond), we focused on the environment with which these aquatic newts and juvenile bullfrogs were currently and primarily in contact. In addition, to assess population-level variation in microbiota, adult newts (N=10/site) from two additional sites were also sampled (Pandapas Pond in Jefferson National Forest, Montgomery County, VA, USA, and Virginia Tech’s Kentland Farm, Montgomery County, VA, USA). Amphibians were captured either by hand or by dip-net. All sampling occurred in summer 2010.

In the field, individual amphibians were rinsed with sterile water to remove transient bacteria (Lauer et al., 2007), then swabbed using sterile, rayon-tipped swabs, which are non-inhibitory to live micro-organisms (Medical Wire & Equipment MW113). The swab was used to examine whole bacterial community structure using bar-coded 454 pyrosequencing. Each individual was swabbed ten strokes along the ventral side and five strokes along each dorsal/lateral side to standardize the sample collection. A fresh pair of gloves was used when handling each individual. Swabs were also used to collect the pond water and pond substrate samples at three randomly selected locations around the ponds. For water sampling, a sterile swab was moved around in the water for 5 s at a depth of ∼10 cm. Substrate from the pond bottom (including mud and decaying leaves) was collected with a dip-net then swabbed for 5 s. We sampled the top ∼15 cm of substrate, as this is the part of the substrate to which the amphibians are likely exposed. Swabs were immediately placed on ice and were then frozen at −20 C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction, amplification and pyrosequencing

Whole-community DNA was extracted from each of the 48 swabs using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. The V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR with primers 27F–338R (Fierer et al., 2008). The reverse primers contained unique 12-bp error-correcting Golay barcodes used to tag each PCR product (Fierer et al., 2008), which allowed us to assign sequences to each sample based on the unique barcode. All samples were run in triplicate, and no-template controls were run for each sample. After equimolar pooling of PCR amplicons, 12 samples were run on each of four regions using the Roche 454 FLX Titanium platform at the University of South Carolina Environmental Genomics Core Facility.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

The total number of 454 sequences generated was 323 979, with an average number of sequences per sample of 6750 (range 86–31 153). Sequences were analyzed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (MacQIIME, v. 1.5.0) pipeline (Caporaso et al., 2010b). Sequences were de-multiplexed and filtered based on read length (minimum of 200 bp), quality score (minimum of 25) and number of errors in the barcode (maximum of 1.5). After denoising with Denoiser (Reeder and Knight, 2010), sequences were clustered into OTUs (operational taxonomic units) at 97% sequence similarity using the uclust method (Edgar, 2010). The most abundant sequence in a cluster was assigned as the representative sequence for that OTU. Sequences were aligned to the Greengenes 12_10 reference database (DeSantis et al., 2006) using PyNAST (Caporaso et al., 2010a) and assigned taxonomy using RDP classifier (Wang et al., 2007). Only OTUs containing 0.001% of the total number of sequences were used in analyses (Bokulich et al., 2013). To standardize sampling effort across samples, the samples were rarefied at 1000 sequences, resulting in final sample sizes of Mountain Lake bullfrogs, N=11, Mountain Lake newts, N=7, Pandapas Pond newts, N=9, and Kentland Farm newts, N=8. Final pond substrate and water samples remained unchanged, N=3 each.

The core microbiota was defined as the set of OTUs present on 80% or more of individuals in a host population. To assess beta-diversity, we applied Nonmetric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS; Kruskal, 1964) based on the Bray–Curtis measure of dissimilarity (Bray and Curtis, 1957) in OTU relative abundances across samples. In addition, we used the phylogenetic-based weighted UniFrac distance metric (Lozupone et al., 2011) to evaluate beta-diversity. The results using Bray-Curtis and weighted UniFrac were the same, and only the results for Bray-Curtis are presented. OTU relative abundances were computed for each sample by dividing the number of reads assigned to the OTU by the total number of rarefied reads for that sample.

Ordinations are useful in that the interpretation of pairwise relative distances as a reflection of observation similarities is clear; for example, samples in an ordination that are close are more similar to one another (across all dimensions) than those that are far apart. To decipher whether variation in the pairwise distances can be explained by covariates, we applied Adonis (available in the vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2013) in R (version 2.15.1; www.r-project.org); Anderson, 2001). Specifically, Adonis is an analytical method that is comparable to a non-parametric version of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and was applied to test whether microbial communities were significantly different across sample source or site. Measures of significance are interpreted like a P-value and, for this application, were based on 999 permutations. It has been shown that Adonis may confound location and dispersion effects (Anderson, 2001), but it is less sensitive to dispersion than some of its alternatives, such as analysis of similarities, or ANOSIM (Oksanen et al., 2013). Separate analyses were conducted for the within-site (Mountain Lake bullfrogs, newts, pond water and pond substrate) and across-site (Mountain Lake, Pandapas Pond and Kentland Farm newts) data sets.

Venn diagrams were created using the program Venny (Oliveros, 2007) to visualize the OTUs that were shared between bullfrogs, newts, pond substrate and pond water at Mountain Lake and between newts at the three sites. To examine the relationship between amphibian and environmental microbes, we calculated the proportion of amphibian OTUs that were also found in the environment and used a Fisher’s exact test to compare these proportions across the two amphibian species. We then compared the mean relative abundances of OTUs that were shared between newts or bullfrogs and pond water and pond substrate. Mean relative abundances of OTUs were calculated by dividing the sum of relative abundances across all samples in a group by the total number of samples in that group.

We compared the bacterial communities found on our Virginia amphibians with a previous published data set of skin microbes on Colorado amphibian species to begin to synthesize our knowledge of the amphibian skin microbiome. Also using bar-coded pyrosequencing, McKenzie et al. (2011) sampled the skin microbial communities of three amphibian species (tiger salamanders, Ambystoma tigrinum, N=12; Western chorus frogs, Pseudacris triseriata, N=13; and Northern leopard frogs, Lithobates pipiens, N=7) across two to four sites each, for a total of 32 individuals. Using the representative sequences of our amphibian-associated OTUs as a reference database, we clustered the sequences from McKenzie et al. (2011) at 97% similarity using the closed-reference OTU picking method in QIIME. The sequences from McKenzie et al. (2011) that we used for this analysis were quality-filtered, but not previously clustered into OTUs. The resulting closed-reference data set was then rarefied to an even sampling depth of 80 sequences/sample, which produced 180 OTUs.

Results

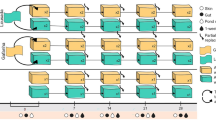

Within the Mountain Lake site, red-spotted newts, bullfrogs, pond water and pond substrate had distinct microbial communities based on NMDS ordination (Figure 1; NMDS stress: 0.16; Adonis F=4.555, P=0.001, R2=0.41). Bullfrogs also had greater individual variability in microbial communities than newts as indicated in the greater distances among bullfrog samples on the NMDS ordination as compared with the newt samples (that is, newts clustered more tightly together than bullfrogs). A total of 595 and 117 OTUs were observed on bullfrogs and newts at Mountain Lake, respectively, with 71 of these OTUs observed on both species (Figure 2). Overall, most amphibian OTUs were not observed in the environmental samples (84%, 538 of 641 total amphibian OTUs). However, newts shared more of their microbes with the environment (38%, 44 of 117 OTUs) than bullfrogs shared with the environment (16%, 94 of 595 OTUs; Fisher’s exact test, P=0.0001; Figure 2). This was the case for both water (newts: 25%, 29 of 117 OTUs; bullfrogs: 11%, 65 of 595; Fisher’s exact test, P=0.0002) and substrate (newts: 17%, 20 of 117 OTUs; bullfrogs: 8%, 49 of 595; Fisher’s exact test, P=0.0056). Lastly, newts across the three sites shared 55 OTUs (Figure 3).

Most OTUs (80%, 82 of 103 OTUs) that were shared between any amphibian host and the environment were at relative abundances in the pond water or substrate of 0.1% or less (Figure 4, cluster of points near origin). The OTUs that were abundant on bullfrog or newt skin were in relatively low abundance in the environment, and, similarly, the more abundant environmental OTUs were in relatively low abundance on bullfrog or newt skin (Figure 4). For example, two OTUs, in the genus Bacillus and family Enterobacteriaceae, dominated the Mountain Lake pond substrate samples, representing 36 and 30%, respectively, of all substrate OTUs. These were present on bullfrogs at relative abundances of 0.05 and 0.08%, and on newts at 0.03 and 2.2%. The most abundant pond water OTU belonged to the ACK-M1 family of the Actinomycetales, representing 18% of pond water OTUs, yet only 0.02 and 0.01% of bullfrog and newt OTUs, respectively.

The general pattern of inversely related relative abundance of the skin microbes and the environmental samples is exemplified by examination of the core skin microbiota (Table 1), which was defined as OTUs that were present on >80% of individual hosts in a population. Bullfrogs and newts at Mountain Lake each had seven OTUs representing the core microbial community (Table 1). Ten of the 11 Mountain Lake amphibian core OTUs were present in the environment at relative abundances at or below 0.1%. The more abundant environmental OTU was a Pseudomonas that was in the pond substrate with a relative abundance of 6.2%. Indeed, of the 29 most abundant substrate OTUs (>0.1% relative abundance), this Pseudomonas OTU was the only one to overlap with the Mountain Lake amphibian core microbiota, and it was actually a core member of all four amphibian populations sampled (Table 1). The distribution of pond water OTUs was more dispersed than the substrate samples, with 70 pond water OTUs present in relative abundances >0.1%. However, again, of that group, only a single Hydrogenophaga OTU appeared as a core member of the newt skin microbiota at Mountain Lake. Furthermore, most of the abundant environmental OTUs (66% of substrate OTUs and 66% of water OTUs) were not observed on any amphibian host, suggesting that amphibian skin is not simply colonized by the abundant environmental microbes.

For newts at Pandapas Pond and Kentland Farm, respectively, 7 and 10 OTUs were observed in >80% of individuals in a population and thus considered core microbes (Table 1). Within newts, across the three sites, newt skin bacterial communities were significantly different from each other (Figure 5; NMDS stress: 0.12; Adonis F=4.000, P=0.001, R2=0.28). Pair-wise comparisons were made between the sites, and the microbial communities at each site were significantly different from each other (KF vs PP: F=4.500, P=0.002; KF vs ML: F=6.926, P=0.003; ML vs PP: F=1.953, P=0.05) despite some overlap in the NMDS ordination (Figure 5). The NMDS ordination demonstrates that the skin microbial communities on the Kentland Farm newts are less variable among individuals than the skin microbial communities on Pandapas Pond and Mountain Lake newts (Figure 5). It is important to note that the Adonis significance test may confound location (across-group variation) and dispersion (within-group variation) effects (Anderson, 2001), such that significant differences may be caused by different within-group variation or different means across groups. To explore the possibility that dispersion was driving the between-group differences, we removed the outliers and re-ran the analyses. With the outliers removed and dispersion effects minimized, the Mountain Lake and Pandapas Pond newt microbial communities become only weakly significantly different (Adonis, ML vs PP: F=2.090, P=0.06), suggesting that dispersion may have a stronger role in the identified differences between those two forested sites. However, both forested sites (ML and PP) remained significantly different from the agricultural Kentland Farm (KF) site following outlier removal (Adonis, KF vs PP: F=4.624, P=0.001; KF vs ML: F=9.412, P=0.004), suggesting that it is group location and not dispersion that drive this pattern.

Despite the distinct clustering of microbial communities across species and sites (Figures 1 and 5), there was some overlap in particular OTUs on the amphibians. Three amphibian core OTUs (in the genera Pseudomonas, Sanguibacter and Varivorax) were present on both bullfrogs and newts in the same pond. The Pseudomonas and Sanguibacter OTUs were also present on newts at all three sites. There was one additional core OTU that was found on newts at all three sites and was not found on the bullfrogs (in the genera Stenotrophomonas; Table 1). The mean relative abundances of the amphibians’ core OTUs ranged from 0.3 to 34.4% (Table 1), suggesting that the amphibians’ core microbiota also tends to contain the more dominant members of their microbial communities. Indeed, with the exception of Pandapas Pond newts, the most dominant OTU (in terms of relative abundance) in each amphibian population was also part of the core microbiota (bolded OTUs in Table 1).

At the phylum level, newts’ and bullfrogs’ microbiota across all sites were dominated by Proteobacteria, followed by Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Figure 6), with mean relative abundances across all samples of 71, 16, 7 and 3%, respectively. When focusing on the 12 bacterial phyla with mean relative abundances >0.1% across all samples, newts at Mountain Lake were dominated by Proteobacteria (96%) with the remaining 11 phyla ranging from 0 to 3.6% in relative abundance. In contrast, bullfrogs at Mountain Lake had a more even representation of these phyla, ranging from 0 to 45% in relative abundances. The newts at Pandapas Pond also had a more even representation of the phyla than newts at Mountain Lake or Kentland Farm (Figure 6).

Of the 875 amphibian OTUs observed in this study, 180 (20.6%) overlapped with those associated with amphibians sampled from Colorado in McKenzie et al. (2011). Five of the 14 newt or bullfrog core OTUs were also detected on Colorado amphibians (underlined in Table 1). A newt core OTU classified as Hydrogenophaga was found on all three amphibian species sampled in Colorado. Newt core OTUs in the genera Stenotrophomonas and Microbacterium were detected on Western chorus frogs and Northern leopard frogs, whereas a newt core OTU classified as Methylotenera was only detected on the Western chorus frog. Lastly, a Pseudomonas OTU that was a member of Virginia bullfrog and newt core microbiotas was also detected on the two Colorado frog species sampled, but not on the tiger salamanders.

Discussion

Our results suggest that amphibian skin harbors microbes that are generally in low abundance in the environment, as opposed to being colonized by microbes that are abundant in the environment. The microbial communities of amphibians and the environment clustered separately in the NMDS ordination; there was very little overlap in the amphibians’ core microbes and the most abundant environmental microbes, and the relative abundances of OTUs that were shared by amphibians and the environment were inversely related. This same pattern has been seen in sponge and squid systems, such that symbionts that are in very low abundance in the surrounding environment are highly abundant in the hosts (Nyholm et al., 2000; Nyholm and McFall-Ngai, 2004; Webster et al., 2010). In these other systems, the mucous layer appears to act as a filter, selecting for certain members of the free-living environmental microbial community, and in some cases specific microbes in the environment may be attracted to host-produced compounds (Bright and Bulgheresi, 2010). Indeed, Lee and Qian (2004) identified potential host chemically mediated control of bacteria on the surface of sponges.

While both symbiont and host factors are important in determining the composition of the microbiota, the amphibian host likely has a strong influence on the composition of microbes inhabiting the skin. Amphibian skin is complex, involving mucous skin secretions, host-produced anti-microbial peptides, microbes and microbially produced metabolites. The components are likely to interact in a complex manner. For example, Myers et al. (2012) found a synergistic interaction between bacterially produced metabolites and host-produced peptides, in terms of inhibition of a fungal pathogen of amphibians. Amphibians produce varying amounts of mucus secretions (Lillywhite and Licht, 1975), which, in addition to preventing desiccation and aiding in skin-shedding and escape from predators, may act to regulate microbial growth. Furthermore, each amphibian species has their own set of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs; Woodhams et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2007a; Daum et al., 2012), with some host species not producing any at all (Conlon, 2011). Some amphibian populations can be differentiated based on their AMPs (Tennessen et al., 2009; Woodhams et al., 2010). These peptides are likely having a role in regulating the growth of certain microbes, leading to amphibian species-specific and population-specific microbiota.

An additional factor that may influence both transmission dynamics and the host-specific nature of amphibian skin microbiota is skin sloughing. Amphibians shed their skin at different intervals, and this interval can further be influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature (Meyer et al., 2012). Meyer et al. (2012) also found that sloughing reduces the abundance of symbiotic skin microbes substantially, although Harris et al. (2009a) found that in a Rana muscosa bioaugmentation study at least some microbes can persist on the skin despite shedding, even without an available environmental inoculum. In terms of transmission, important questions arise, such as whether all symbionts persist on the skin or whether hosts re-acquire at least some of their symbionts from the environment after each sloughing event (intragenerational transmission; Bulgheresi, 2011).

Interestingly, there were six amphibian core OTUs (two newt, three bullfrog and one shared) that were not detected in the environment at all. This could be because these microbes are in such low abundance in the environment that they were simply not detected with our methods, that they are present in a habitat other than the pond water or substrate, such as grass along the edge of the pond, or that they are transmitted vertically or horizontally via conspecifics. However, our results, in combination with other recent studies, suggest that the amphibian skin microbiota is likely to be maintained by a mixture of transmission modes (for example, Banning et al., 2008; Walke et al., 2011; Muletz et al., 2012). This is not unusual in the animal kingdom, as several sponge-symbiont associations are maintained via a combination of vertical and environmental transmission (Schmitt et al., 2008; Webster et al., 2010), and, therefore, the relative importance of the environmental microbe pool varies across host taxa. A lot of progress has been made in understanding the transmission dynamics of the bobtail squid-Vibrio fischeri symbiosis (Nyholm and McFall-Ngai, 2004), which consists of a single cultivable bacterium. In the cases of sponge-associated and amphibian-associated microbiota, the complex and diverse nature of the symbiont communities may make symbiont transmission dynamics more difficult to elucidate (Webster et al., 2010).

We observed differences in microbial communities of juvenile bullfrogs and adult newts at the same site. These species have different life histories, which may, in part, explain differences in their microbial communities. Newts have aquatic embryos that hatch into an aquatic larval stage. The aquatic larvae metamorphose into terrestrial juvenile ‘efts’ before returning to the pond to breed as adults. In contrast, the juvenile bullfrogs had recently metamorphosed and would never have left this site, as they would have developed there from aquatic embryos and larvae.

We also observed differences in microbial communities of newts across three sites, including greater individual variation at Pandapas Pond and Mountain Lake as compared with Kentland Farm. The pond at Kentland Farm is surrounded by a large agricultural experimental farm, whereas the ponds at Pandapas and Mountain Lake are surrounded by forest and fed by creeks or springs. Pandapas Pond is also stocked with fish and is a popular recreation site for humans and their pets, which are additional sources of new and diverse microbes. The isolation of the pond at Kentland Farm and the characteristics of the surrounding habitat may limit the dispersal opportunities for newts at this site, thus limiting microbial sources. Amphibians’ life history and site characteristics appear to have a role in microbial community structure of amphibian skin.

The four most abundant bacterial phyla identified in this study (Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes) are consistent with the dominant groups found on amphibian skin in other studies, including those of other species and that employed different microbial community characterization methods (Culp et al., 2007; Lauer et al., 2007, 2008; Lam et al., 2010; McKenzie et al., 2011). Interestingly, these four dominant amphibian skin bacterial phyla are also the most dominant phyla on human skin, although the order of relative abundance varies (Costello et al., 2009; Grice et al., 2009). A further sequence comparison analysis between this study and data from McKenzie et al. (2011) revealed that ∼20% of Virginia amphibian-associated bacteria were also associated with Colorado amphibians, so there may be some broad-scale similarities in these communities. However, only three of the 12 newt core bacteria in our study were considered core in all three newt populations, and this pattern of intraspecific variation in core or dominant bacteria across populations also appears to be consistent with the results of the study by McKenzie et al. (2011) in Colorado. This suggests that only a subset of the ‘core’ for any given amphibian population might be considered a member of the core microbiota of that species across its broader geographic range.

The devastating amphibian skin disease, chytridiomycosis, is caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd; Berger et al., 1998; Longcore et al., 1999; Lips et al., 2006; Skerratt et al., 2007). Although research examining the role of cutaneous symbionts in preventing chytridiomycosis and Bd infection is growing (Belden and Harris, 2007; Bletz et al., 2013), key questions remain about individual, population and species variation in susceptibility to Bd (Retallick et al., 2004; Daszak et al., 2004; Briggs et al., 2005; Searle et al., 2011). Our results demonstrate that bullfrogs and newts have distinct microbial communities, despite cohabitation in a single pond. This finding of host species-specific microbiota is consistent with another study of amphibian skin microbiota (McKenzie et al., 2011) and could explain some variation in disease susceptibility among species, as some members of amphibians’ natural microbiota can inhibit growth of Bd (Harris et al., 2006; Walke et al., 2011) and appear to have a role in preventing colonization by pathogenic microbes (Harris et al., 2009a, 2009b; Becker and Harris, 2010). Within a species, population-specific microbiota, which we also observed with the newts in our study, could explain variation in disease susceptibility among populations (Lam et al., 2010). Understanding variation in skin microbiota and how microbes are transmitted is a critical step in the development of amphibian probiotics for conservation (Belden and Harris, 2007, Bletz et al., 2013).

By directly assessing the microbial community composition of free-living amphibian hosts and the environmental microbes to which these individuals are exposed, we were able to demonstrate that amphibian skin microbiota is not simply a reflection of the microbes in the environment, but that host species-specific selection for rare environmental microbes is likely occurring. This finding is consistent with other systems, such as squid (Nyholm and McFall-Ngai, 2004), sponges (Webster et al., 2010) and some fishes (Roeselers et al., 2011; Sullam et al., 2012). Amphibian skin microbiota appears to be maintained by a combination of transmission modes, as occurs in other animal-microbe symbioses. Regardless of their transmission mode, endo- and ecto-symbionts exploit a range of fascinating cellular mechanisms to ensure intra- and trans-generational associations with their hosts (Bulgheresi, 2011). Further research into the cellular mechanisms of the complex interactions taking place on amphibian skin will provide insights into the overall ecology and evolution of this symbiosis.

References

Amato KR, Yeoman CJ, Kent A, Righini N, Carbonero F, Estrada A et al. (2013). Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. ISME J 7: 1344–1353.

Anderson MJ . (2001). A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol 26: 32–46.

Banning JL, Weddle AL, Wahl GW, Simon MA, Lauer A, Walters RL et al. (2008). Antifungal skin bacteria, embryonic survival, and communal nesting in four-toed salamanders, Hemidactylium scutatum. Oecologia 156: 423–429.

Becker MH, Harris RN . (2010). Cutaneous bacteria of the redback Salamander prevent morbidity associated with a lethal disease. PLoS One 5: e10957.

Belden LK, Harris RN . (2007). Infectious diseases in wildlife: the community ecology context. Front Ecol Environ 10: 533–539.

Berger L, Speare R, Daszak P, Green DE, Cunningham AA, Goggin CL et al. (1998). Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9031–9036.

Bletz MC, Loudon AH, Becker MH, Bell SC, Woodhams DC, Minbiole KPC et al. (2013). Mitigating amphibian chytridiomycosis with bioaugmentation: characteristics of effective probiotics and strategies for their selection and use. Ecol Lett 16: 807–820.

Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R et al. (2013). Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods 10: 57–59.

Bray JR, Curtis JT . (1957). An ordination of upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr 27: 325–349.

Briggs CJ, Vredenburg VT, Knapp RA, Rachowicz LJ . (2005). Investigating the population-level effects of chytriomycosis: an emerging infectious disease of amphibians. Ecology 86: 3149–3159.

Bright M, Bulgheresi S . (2010). A complex journey: transmission of microbial symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 218–230.

Bulgheresi S . (2011). Microbial symbiont transmission: basic principles and dark sides. In: Rosenberg E and Gophna U (eds) Beneficial Microorganisms in Multicellular Life Forms. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 299-311.

Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R . (2010a). PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26: 266–267.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. (2010b). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7: 335–336.

Conlon JM . (2011). The contribution of skin antimicrobial peptides to the system of innate immunity in anurans. Cell Tissue Res 343: 201–212.

Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R . (2009). Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326: 1694–1697.

Culp CE, Falkinham JO, Belden LK . (2007). Identification of the natural bacterial microflora on the skin of eastern newts, bullfrog tadpoles and redback salamanders. Herpetologica 63: 66–71.

Damiani C, Ricci I, Crotti E, Rossi P, Rizzi A, Scuppa P et al. (2008). Paternal transmission of symbiotic bacteria in malaria vectors. Curr Biol 18: R1087–R1088.

Daszak P, Strieby A, Cunningham AA, Longcore JE, Brown CC, Porter D . (2004). Experimental evidence that the bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) is a potential carrier of chytridiomycosis, an emerging fungal disease of amphibians. Herpetol J 14: 201–207.

Daum JM, Davis LR, Bigler L, Woodhams DC . (2012). Hybrid advantage in skin peptide immune defenses of water frogs (Pelophylax esculentus) at risk from emerging pathogens. Infect Genet Evol 12: 1854–1864.

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 5069–5072.

Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA . (2007). An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 449: 811–818.

Edgar RC . (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461.

Ewald PW . (1987). Transmission modes and evolution of the parasitism-mutualism continuum. Ann N Y Acad Sci 503: 295–306.

Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, Knight R . (2008). The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17994–17999.

Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC et al. (2009). Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324: 1190–1192.

Harris RN, James TY, Lauer A, Simon MA, Patel A . (2006). Amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is inhibited by the cutaneous bacteria of amphibian species. Ecohealth 3: 53–56.

Harris RN, Brucker RM, Walke JB, Becker MH, Schwantes CR, Flaherty DC et al. (2009a). Skin microbes on frogs prevent morbidity and mortality caused by a lethal skin fungus. ISME J 3: 818–824.

Harris RN, Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, Alford RA . (2009b). Addition of antifungal skin bacteria to salamanders ameliorates the effects of chytridiomycosis. Dis Aquat Organ 83: 11–16.

Heath-Heckman EAC, Peyer SM, Whistler CA, Apicella MA, Goldman WE, McFall-Ngai MJ . (2013). Bacterial bioluminescence regulates expression of a host cryptochrome gene in the squid-Vibrio symbiosis. mBio 4 2: e00167–13.

Hong P-Y, Wheeler E, Cann IKO, Mackie RI . (2011). Phylogenetic analysis of the fecal microbial community in herbivorous land and marine iguanas of the Galápagos Islands using 16S rRNA-based pyrosequencing. ISME J 5: 1461–1470.

Hosokawa T, Kikuchi Y, Fukatsu T . (2007). How many symbionts are provided by mothers, acquired by offspring, and needed for successful vertical transmission in an obligate insect-bacterium mutualism? Mol Ecol 16: 5316–5325.

Jones KM, Kobayashi H, Davies BW, Taga ME, Walker GC . (2007). How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: the Sinorhizobium–Medicago model. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 619–633.

Kaltenpoth M, Engl T . (2013). Defensive microbial symbionts in Hymenoptera. Funct Ecol 28: 315–327.

Kikuchi Y, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T . (2007). Insect-microbe mutualism without vertical transmission: a stinkbug acquires a beneficial gut symbiont from the environment every generation. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4308–4316.

Kruskal JB . (1964). Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika 29: 1–27.

Lam BA, Walke JB, Vredenburg VT, Harris RN . (2010). Proportion of individuals with anti-Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis skin bacteria is associated with population persistence in the frog Rana muscosa. Biol Conserv 143: 529–531.

Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, André E, Duncan K, Harris RN . (2007). Common cutaneous bacteria from the eastern red-backed salamander can inhibit pathogenic fungi. Copeia 2007: 630–640.

Lauer A, Simon MA, Banning JL, Lam BA, Harris RN . (2008). Diversity of cutaneous bacteria with antifungal activity isolated from female four-toed salamanders. ISME J 2: 145–157.

Lauzon CR, McCombs SD, Potter SE, Peabody NC . (2009). Establishment and vertical passage of Enterobacter (Pantoea) agglomerans and Klebsiella pneumoniae through all life stages of the Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 102: 85–95.

Lee OO, Qian P-Y . (2004). Potential control of bacteria epibiosis on the surface of the sponge Mycale adhaerens. Aquat Microb Ecol 34: 11–21.

Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS et al. (2008a). Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320: 1647–1651.

Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI . (2008b). Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev 6: 776–788.

Lillywhite HB, Licht P . (1975). A comparative study of integumentary mucous secretions in amphibians. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 51: 937–941.

Lips KR, Brem F, Brenes R, Reeve JD, Alford RA, Voyles J et al. (2006). Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3165–3170.

Longcore JE, Pessier AP, Nichols DK . (1999). Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis gen et sp nov, a chytrid pathogenic to amphibians. Mycologia 91: 219–227.

Lozupone C, Lladser ME, Knights D, Stombaugh J, Knight R . (2011). UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J 5: 169–172.

McKenzie VJ, Bowers RM, Fierer N, Knight R, Lauber CL . (2011). Co-habiting amphibian species harbor unique skin bacterial communities in wild populations. ISME J 6: 588–596.

Meyer EA, Cramp RL, Bernal MH, Franklin CE . (2012). Changes in cutaneous microbial abundance with sloughing: possible implications for infection and disease in amphibians. Dis Aquat Organ 101: 235–242.

Moran NA . (2003). Tracing the evolution of gene loss in obligate bacterial symbionts. Curr Opin Microbiol 6: 512–518.

Muegge BD, Kuczynski J, Knights D, Clemente JC, González A, Fontana L et al. (2011). Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 332: 970–974.

Muletz CR, Myers JM, Domangue RJ, Herrick JB, Harris RN . (2012). Soil bioaugmentation with amphibian cutaneous bacteria protects amphibian hosts from infection by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Biol Conserv 152: 119–126.

Myers JM, Ramsey JP, Blackman AL, Nichols AE, Minbiole KPC, Harris RN . (2012). Synergistic inhibition of the lethal fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis: The combined effects of symbiotic bacterial metabolites and antimicrobial peptides of the frog Rana muscosa. J Chem Ecol 38: 958–965.

Nayak SK . (2010). Role of gastrointestinal microbiota in fish. Aquac Res 41: 1553–1573.

Nyholm SV, Stabb EV, Ruby EG, McFall-Ngai MJ . (2000). Establishment of an animal-bacterial association: Recruiting symbiotic vibrios from the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10231–10235.

Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai M . (2004). The winnowing: establishing the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 632–642.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O'Hara RB et al. (2013). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-7 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Oliveros JC . (2007). VENNY. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn Diagrams http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

Reeder J, Knight R . (2010). Rapidly denoising pyrosequencing amplicon reads by exploiting rank-abundance distributions. Nat Methods 7: 668–669.

Retallick RWR, McCallum H, Speare R . (2004). Endemic infection of the amphibian chytrid fungus in a frog community post-decline. PLoS Biol 2: e351.

Roeselers G, Mittge EK, Stephens WZ, Parichy DM, Cavanaugh CM, Guillemin K et al. (2011). Evidence for a core gut microbiota in the zebrafish. ISME J 5: 1595–1608.

Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, Zilber-Rosenberg I . (2007). The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 355–362.

Sachs JL, Essenberg CJ, Turcotte MM . (2011a). New paradigms for the evolution of bacterial infections. Trends Ecol Evol 26: 202–209.

Sachs JL, Skophammer RG, Regus JU . (2011b). Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10800–10807.

Schmitt S, Angermeier H, Schiller R, Lindquist N, Hentschel U . (2008). Molecular microbial diversity survey of sponge reproductive stages and mechanistic insights into vertical transmission of microbial symbionts. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 7694–7708.

Searle CL, Gervasi SS, Hua J, Hammond JI, Relyea RA, Olson DH et al. (2011). Differential Host Susceptibility to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, an Emerging Amphibian Pathogen. Conserv Biol 25: 965–974.

Skerratt LF, Berger L, Speare R, Cashins S, McDonald KR, Phillott AD et al. (2007). Spread of chytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction of frogs. EcoHealth 4: 125–134.

Sullam KE, Essinger SD, Lozupone CA, O’Connor MP, Rosen GL, Knight R et al. (2012). Environmental and ecological factors that shape the gut bacterial communities of fish: a meta-analysis. Mol Ecol 21: 3363–3378.

Tennessen JA, Woodhams DC, Chaurand P, Reinert LK, Billheimer D, Shyr Y et al. (2009). Variations in the expressed antimicrobial peptide repertoire of northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens) populations suggest intraspecies differences in resistance to pathogens. Dev Comp Immunol 33: 1247–1257.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI . (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444: 1027–1031.

Walke JB, Harris RN, Reinert LK, Rollins-Smith LA, Woodhams DC . (2011). Social immunity in amphibians: evidence for vertical transmission of innate defenses. Biotropica 43: 396–400.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . (2007). Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5261–5267.

Webster NS, Taylor MW, Behnam F, Lücker S, Rattel T, Whalan S et al. (2010). Deep sequencing reveals exceptional diversity and modes of transmission for bacterial sponge symbionts. Environ Microbiol 12: 2070–2082.

Wenzel M, Schönig I, Berchtold M, Kämpfer P, König H . (2002). Aerobic and facultatively anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria from the gut of the termite Zootermopsis angusticollis. J Appl Microbiol 92: 32–40.

Woodhams DC, Rollins-Smith LA, Carey C, Reinert L, Tyler MJ, Alford RA . (2006a). Population trends associated with skin peptide defenses against chytridiomycosis in Australian frogs. Oecologia 146: 531–540.

Woodhams DC, Voyles J, Lips KR, Carey C, Rollins-Smith LA . (2006b). Predicted disease susceptibility in a panamanian amphibian assemblage based on skin peptide defenses. J Wildlife Dis 42: 207–218.

Woodhams DC, Ardipradja K, Alford RA, Marantelli G, Reinert LK, Rollins-Smith LA . (2007a). Resistance to chytridiomycosis varies among amphibian species and is correlated with skin peptide defenses. Animal Conserv 10: 409–417.

Woodhams DC, Vredenburg VT, Simon MA, Billheimer D, Shakhtour B, Shyr Y et al. (2007b). Symbiotic bacteria contribute to innate immune defenses of the threatened mountain yellow-legged frog Rana muscosa. Biol Conserv 138: 390–398.

Woodhams DC, Kenyon N, Bell SC, Alford RA, Chen S, Billheimer D et al. (2010). Adaptations of skin peptide defences and possible response to the amphibian chytrid fungus in populations of Australian green-eyed treefrogs Litoria genimaculata. Divers Distrib 16: 703–712.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Virginia’s Mountain Lake Biological Station, Virginia Tech’s Kentland Farm, and the Jefferson National Forest for allowing us to conduct research on their lands. We also thank K. Walke for field assistance, and V. McKenzie for providing us with access to the sequence files from her 2011 study. This research was funded by the Morris Animal Foundation, the Fralin Life Science Institute at Virginia Tech and the National Science Foundation (DEB-1136640).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walke, J., Becker, M., Loftus, S. et al. Amphibian skin may select for rare environmental microbes. ISME J 8, 2207–2217 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.77

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.77

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

First Report of Culturable Skin Bacteria in Melanophryniscus admirabilis (Admirable Redbelly Toad)

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Factors Influencing Bacterial and Fungal Skin Communities of Montane Salamanders of Central Mexico

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

From Alien Species to Alien Communities: Host- and Habitat-Associated Microbiomes in an Alien Amphibian

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

A Variety of Fungal Species on the Green Frogs’ Skin (Pelophylax esculentus complex) in South Banat

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Signatures of functional bacteriome structure in a tropical direct-developing amphibian species

Animal Microbiome (2022)