Abstract

For any enzyme-catalyzed reaction to occur, the corresponding protein-encoding genes and transcripts are necessary prerequisites. Thus, a positive relationship between the abundance of gene or transcripts and corresponding process rates is often assumed. To test this assumption, we conducted a meta-analysis of the relationships between gene and/or transcript abundances and corresponding process rates. We identified 415 studies that quantified the abundance of genes or transcripts for enzymes involved in carbon or nitrogen cycling. However, in only 59 of these manuscripts did the authors report both gene or transcript abundance and rates of the appropriate process. We found that within studies there was a significant but weak positive relationship between gene abundance and the corresponding process. Correlations were not strengthened by accounting for habitat type, differences among genes or reaction products versus reactants, suggesting that other ecological and methodological factors may affect the strength of this relationship. Our findings highlight the need for fundamental research on the factors that control transcription, translation and enzyme function in natural systems to better link genomic and transcriptomic data to ecosystem processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Describing the relationship between microbial community structure and ecosystem function has emerged as an important yet elusive target in microbial ecology (Fuhrman, 2009). To evaluate these linkages, many studies use molecular techniques, including quantitative PCR (qPCR), reverse-transcription qPCR (Liu et al., 2010; Shannon et al., 2011), microarrays (Taroncher-Oldenburg et al., 2003; Kang et al., 2013) and, most recently, metagenomics (Tyson et al., 2004; Mackelprang et al., 2011; Fierer et al., 2012; Yau et al., 2013). These techniques measure the relative abundances of nucleic acids encoding proteins that catalyze biogeochemical reactions, which we refer to as protein-encoding genes and transcripts (or henceforth as gene or transcript). The use of these approaches to compare gene or transcript abundance with rates of biogeochemical processes stems from the ‘sequence hypothesis’ proposed in the 1950s and now a central tenet of molecular biology, where the transference of biological information is sequential, from gene(s) to transcript(s) to protein synthesis, finally leading to the resultant enzyme-catalyzed chemical reaction (Crick, 1958). On the most fundamental level, genes are prerequisites for any enzyme-catalyzed reaction and should therefore correlate. However, the relationship between gene and transcript abundances and the processes they facilitate can be obscured by various factors including habitat attributes, complexity of biogeochemical pathways and differences in the turnover time of nucleic acids and reaction products. In addition, methodological constraints such as extraction efficiency, PCR biases and primer design can affect any apparent relationship between gene and function. Nonetheless, many studies assume that there is a quantitative relationship between functional enzymes and the processes that they catalyze. Our goal in this review was to evaluate whether this assumption is supported by data.

To address how well gene copy or transcript abundance correlates with process, we conducted a meta-analysis of microbial genes with known matching functions in environmental habitats. Data were assembled from a wide range of studies to examine explanatory value of certain study-specific conditions, like specific gene type, habitat, DNA versus RNA and/or reaction states.

We obtained data for our meta-analysis by identifying studies that quantified genes or transcripts, which primarily involved C- and N-cycling genes using Google Scholar and ISI Web of Knowledge (for published data sets) and ProQuest Dissertation & Theses Database (to access the gray literature). We included unpublished literature to minimize potential publication biases against studies that found nonsignificant or weak correlations (Koricheva et al., 2013). Searches were limited to studies published after 2005, matching the time frame for when qPCR methods were optimized and routinely used. We analyzed only studies using qPCR, because it is the most well established and most quantitative method. We used the following search phrases to identify all potentially relevant studies for the initial literature search: ‘functional gene expression and microb*’, ‘qpcr and microb*’, ‘quantitative pcr and microb*’ and ‘<gene name> and gene expression’. Data were then extracted from figures using PlotDigitizer (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net/), which we validated by inputting plots of known values to determine the accuracy and precision of the retrieved digitized data. Studies reporting log-transformed gene counts were antilog converted, and those studies that reported gene counts per unit nucleic acid were excluded as the units must be comparable to that of the process to appropriately assess correlation strength.

We tested for bias in the final database in two ways. First, funnel plots of individual s.e. against residuals from the random-effects model did not show asymmetry using an Egger regression test (Viechtbauer, 2010). We also assessed the database for publication bias using Rosenthal’s estimation of the fail-safe n, which calculates the number of studies yielding null outcomes that would need to be added to have a significant influence on the outcome of the existing set of studies in the database. The fail-safe n estimation must then be larger than five times n samples plus ten to assume a robust existing data set (Rosenthal, 1991), which was true for our data set.

Statistical analyses were performed with the ‘metafor’ package in R (version 3.0.2; Viechtbauer, 2010), and a Fisher Z-transformed Pearson product-moment test of the correlations between genes and corresponding processes for the individual effect size (Zr=0.5 × ln[(1+r)/(1−r)]). To account for the variable number of observations used to calculate a single effect size, we weighted the correlation by the inverse of the asymptotic variance (VZr=1/(n−3)) (Aloe and Becker, 2009; Koricheva et al., 2013), which allowed us to treat effect sizes equally. To select the appropriate statistical model, we tested for homogeneity of all the effects, which was rejected, Q=3827, df=223, P<0.0001, indicating that the distribution of true individual effect sizes was not uniformly distributed. Therefore, to assess the ability of the categorical moderators (that is, nucleic acid form, process dynamics, biome type, functional reaction state, gene type (Table 1) and habitat type) to explain the heterogeneity in the relationship among nucleic acid and biogeochemical processes, we used random-effects models (Viechtbauer, 2010; Koricheva et al., 2013), with an unbiased restricted maximum-likelihood estimator of aggregate effect sizes, as it is optimal for use in meta-analyses (Viechtbauer, 2010) to assess aggregate effect sizes and confidence intervals.

We identified 9584 candidate studies that examined C and N genes and/or transcripts. Of these studies, 415 met the initial screening criteria for the meta-analysis (Figure 1). We then removed studies that had mismatched gene and function or those that had not quantified or not reported the corresponding function. This filtering step reduced our analysis to 59 studies containing 224 observations where qPCR was used to measure gene or transcript abundances as well as the reaction precursor immediate reaction product or flux from one nutrient pool to the other on the same environmental sample (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 1). The 88% reduction (from 415 to 59 studies) in studies for our meta-analysis database does not suggest that qPCR is not widely used to gain inference about biogeochemical functions (Figure 1). Instead, most studies were excluded because (1) they only examined gene or transcript abundance (and not function) or (2) because the measured gene was not directly involved in the biogeochemical sub-process that was assessed. This suggests that gene abundances are often assumed to correlate with the related process without any evaluation of that relationship.

Overall effect sizes for the relationship between protein-encoding gene or transcript abundance and corresponding processes by categorical moderator. The Zr=0 line indicates no correlation, with positive and negative values indicating the directionality of the relationship. Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals of each effect, with bars not crossing Zr=0 indicative of a significant correlation. Q-test significance codes: ***P<0.001, **P=0.001, *P=0.05, ċP=0.1, nsP>0.1.

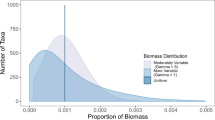

Contrary to the common assumption that gene abundances should be consistently correlated with process, we found extensive heterogeneity among the effect sizes of individual studies included in our meta-analysis. Overall, the abundances of genes were significantly positively correlated with process (r=0.26, P<0.0001, n=224; Figure 2), although the distribution of effect sizes was centered at Zr=0.26 (Figure 2), and resembled a normal distribution (Supplementary Figure 1). Only 38% of individual effects were significantly positively correlated, whereas nearly twice as many were either negatively correlated or showed no significant relationship. To evaluate whether gene or transcript copy abundance was more likely to be correlated with process rates, we separated the predictors by nucleic acid type (DNA versus RNA). We found a significant positive correlation between gene abundance (DNA) and process (r=0.30, P<0.0001, n=189), whereas transcript abundances (RNA) were not significantly correlated (r=0.08, P=0.60, n=35). Even though the sizes of these categories are substantially different, the statistical analysis we used accounts for the difference in sample size when determining the aggregate effect size and confidence intervals (Nakagawa and Cuthill, 2007). The lack of correlation between transcript abundance and processes may be attributed to the rapid degradation of RNA in the environment, with the half-life of transcripts being reported to be as short as 30 s in some habitats (Moran et al., 2013). In addition, the production rate of transcripts may not have a 1:1 relationship between enzyme activities and/or process rates, as multiple proteins can be translated from the same transcript molecule (Moran et al., 2013). Therefore, transcript abundance may track short-term processes (seconds to minutes), whereas gene abundance may be more reflective of microbial process performance potential integrated over longer timescales (hours to days or longer).

We also examined whether gene abundances correlated more strongly with the reaction product or with reactant, as which side of the reaction is measured might influence the correlation strength. However, both reactants (r=0.23, P=0.0051, n=111) and products (r=0.30, P=0.0003, n=113) showed significant positive correlations with corresponding process and similar effect strengths.

When we compared gene–function relationships among terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, we found that terrestrial studies exhibited significant positive correlations between the abundance of genes and processes (r=0.28, P<0.0001, n=172), whereas those from aquatic studies did not (r=0.21, P=0.09, n=52). This finding may reflect inherent differences between these habitats, due to a more rapid temporal decoupling of organisms and biogeochemical reactants in aquatic habitats where the matrix is more temporally static than soils. Within aquatic and terrestrial biomes, we also examined more specific habitat types and found that agricultural systems and coastal aquatic systems exhibited a significant positive gene–function relationship ((r=0.34, P<0.0001, n=110) and (r=0.60, P=0.02, n=9), respectively), whereas other habitat types (forest, grassland, meadow, tundra, estuary and lake; Figure 2) did not show a significant relationship. The strength of the correlation between agricultural and coastal studies may be due to strong signal-to-noise ratios associated with fertilizer at agricultural sites, which due to well-documented runoff and connectivity may also impact coastal ecosystems. As the number of studies in each habitat category is small, additional, well-designed experiments are needed to thoroughly examine the validity of these trends.

It has previously been proposed that biogeochemical processes that are narrowly distributed among bacterial or fungal taxa may be more likely to be constrained by microbial community composition than those biogeochemical processes conducted by a broader phylogenetic suite of organisms (Schimel, 1995; Schimel et al., 2005). We extended this concept to hypothesize that narrow processes should exhibit a stronger correlation between gene abundance and process rate than broad processes. To test this, we examined the data using gene type as the categorical variable and found that only ammonia mono-oxygenases (both bacterial and archaeal amoA) and nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS), both considered to be narrowly regulated processes, yielded significant positive correlations with corresponding process rates ((r=0.42, P=0.03, n=21), (r=0.42, P=0.03, n=21), (r=0.30, P=0.03, n=42) and (r=0.28, P=0.04, n=39), respectively). Other genes, whether broadly (that is, pmoA) or narrowly (that is, mcrA) distributed across taxa, were not significantly correlated with process rates (Figure 2). The lack of correlation for certain genes may simply be due to the few available studies from our literature search, which yielded only one study each for the following: mcrA, nidA, nrfA and PAHgn, none of which showed significant correlations between gene and the corresponding process. However, it is also likely that biological factors may obscure the relationship. The potential impact of aggregated processes likely obscures the gene–function correlation. For instance, nifH gene abundance may diverge from NH4+ concentrations because NH4+ is also generated by nitrogen mineralization, independent of microbial N fixation (Chapin et al., 2002), and gross rates of N fixation are rarely measured. Alternatively, certain archaeal clades of methanogens also contain nifH-like genes (Dang et al., 2009), which, if they are substantial contributors, may be unaccounted for in gene abundance estimates where the qPCR primers only target bacterial N fixers.

Additional reasons for gene-process decoupling include methodological complications in quantifying rates of biogeochemical processes. For instance, the sequential reduction of nitrogen from NO3− to N2 gas during denitrification is a complex pathway, where the additional contribution of NO from the anaerobic oxidation of NH3, or potentially Annamox (anaerobic ammonium oxidation), may further obscure the relationship between nar genes and denitrification rates (Strous et al., 1999). In addition, many studies measure NO3− concentrations in conjunction with amoA gene abundance. NO2− and NO3− gross fluxes are difficult to assess, as both molecules are mobile and are rapidly assimilated by other microbes. Finally, non-biological reduction of NO2− to NO, or ‘chemodenitrification’ (Chapin et al., 2002), may also obscure the gene–function relationship of the early denitrification steps.

Coupled biogeochemical reactions can make it difficult to detect relationships between a pool and a rate. For instance, the select clades of methanogens using mcrA genes to produce CH4 are spatially separated from the broad range of microbes that consume CH4 in soils (Brune et al., 2000). However, if both methanotrophy and methanogenesis rates are high, then the CH4 pool might be smaller than what the mcrA counts would predict and larger than what pmoA genes might suggest (Poret-Peterson et al., 2008). Although the number of studies that examined CH4 production and consumption in the meta-analysis was small (n=8), neither the mcrA nor the pmoA gene abundances were significantly correlated with CH4 net fluxes, possibly due to the competing influences of methanogenesis and methanotrophy on changes in the CH4 pool.

We examined studies that measured both AOA (archaeal amoA) and AOB (bacterial amoA) to determine whether correlations improved when aggregating gene analogs. Possession of the amoA gene was originally thought to be restricted to clades in the bacterial domain (AOB), but the discovery of amoA gene homologs in archaea (AOA) (Venter et al., 2004) and subsequent clarification of their potential importance in nitrification (Francis et al., 2005) indicated that neither AOA nor AOB abundances alone may accurately predict nitrification rates. However, based on our meta-analysis, AOA+AOB (r=0.12, P=0.33, n=28) showed no enhancement of correlation strength over either AOA (r=0.09, P=0.46, n=28) or AOB (r=0.43, P=0.0001, n=28) alone, which may be due to the distinct niche requirements between the two domains of ammonia oxidizers. The archaeal and bacterial amoA functional clades are phylogenetically narrow, which may influence the strength of the correlation between the abundance of AOA and AOB in the environment and ammonia oxidation. Also, the two domains of ammonia oxidizers likely flourish under distinct environmental conditions, with AOA being more prevalent in low-pH habitats (Zhang et al., 2010), further highlighting the importance of measuring the abundance of both domains as a more accurate reflection of nitrifying potential.

As genes are ultimately translated into enzymes catalyzing biogeochemical reactions, they may be more strongly correlated with fluxes than with pools of reactants or products. On the other hand, the abundance of protein-encoding genes itself is a pool rather than a flux, and therefore it is likely that they correlate more with a pool than a flux. Despite a smaller sample size, the correlation between gene abundance and process flux showed a strong positive correlation (r=0.50, P<0.0001, n=76), whereas correlation with pool size was not significant (r=0.13, P=0.08, n=148). This is likely because pool sizes are affected not only by rates of production but also by transfer, consumption and loss.

Our results suggest that, although gene abundance may be an accurate reflection of a given microbial physiological pathway, comparing it with the corresponding biogeochemical process or pool is likely to reveal an even more complex story. For example, reactant pools may frequently be assimilated, leached or re-routed through other biochemical pathways independent of the pathway that corresponds to the gene of interest. The advent of relatively new technologies like gene microarrays (He et al., 2007) and metagenomics (Tyson et al., 2004; Mackelprang et al., 2011; Fierer et al., 2012; Yau et al., 2013) has allowed researchers to rapidly assess more genes compared with qPCR techniques. However, the use of enticing new technologies for assessing gene abundance is also susceptible to many of the same biases that obscure the links between molecular information and biogeochemical processes illustrated by the meta-analysis presented here.

The quantification of genes through qPCR, gene microarrays and now metagenomics is widespread, but few studies have examined the ability of these metrics to predict process rates. At the broadest level, we found a positive relationship between gene abundance and process among all studies, but the broad variation in correlation strengths shows that gene abundances cannot be used a priori as a proxy for biogeochemical processes. Rather, these relationships need to be examined for each study system before gene abundance can be used to infer microbial biogeochemical process. When multiple studies were examined, the concentration of products or reactants rarely correlated with gene abundance (38%). Even in the cases where the correlations are strongly positive, they should not be interpreted as demonstrating causation without further evidence. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in environmental conditions, such as anoxic/oxic and water and/or nutrient availability, may not track the variability of corresponding gene abundance in space and time due to different residence times of these indices. Monitoring gene abundance itself may be useful for determining the variability of that particular organism, but that may not explain fluctuations in the corresponding process. Therefore, studies whose main objective is to examine a particular biogeochemical process may not require, or even be hindered by inclusion gene abundance for determining and predicting process (Graham et al., 2014). However, state-of-the-art technologies, like metagenomic assessment of protein-encoding genes, may more accurately reflect process, as they capture more gene diversity (Tyson et al., 2004; Mackelprang et al., 2011). In addition, quantifying expressed proteins using metaproteomics may prove to be a robust indicator of corresponding function(s). Our findings point to a critical need for more fundamental studies on the factors controlling gene abundance, transcription, translation and enzyme activity, so that we can better interpret the potential for patterns in gene or transcript abundance in a broad range of environments if genes will inform us about fundamental ecosystem processes.

References

Aloe AM, Becker BJ . (2009). Teacher verbal ability and school outcomes: where is the evidence? Educ Res 38: 612–624.

Braker G, Fesefeldt A, Witzel K . (1998). Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 3769–3775.

Braker G, Tiedje JM . (2003). Nitric oxide reductase (norB) genes from pure cultures and environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 3476–3483.

Brezna B, Khan AA, Cerniglia CE . (2003). Molecular characterization of dioxygenases from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading Mycobacterium spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett 223: 177–183.

Brune A, Frenzel P, Cypionka H . (2000). Life at the oxic-anoxic interface: microbial activities and adaptations. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24: 691–710.

Chapin FS, Matson PA, Mooney HA . (2002) Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA.

Crick F . (1958). On protein synthesis. Symp Soc Exp Biol 12: 138–163.

Dang H, Luan X, Zhao J, Li J . (2009). Diverse and novel nifH and nifH-like gene sequences in the deep-sea methane seep sediments of the okhotsk sea. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 2238–2245.

Fierer N, Leff JW, Adams BJ, Nielsen UN, Bates ST, Lauber CL et al. (2012). Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 21390–21395.

Flanagan DA, Gregory LG, Carter JP, Karakas-Sen A, Richardson DJ, Spiro S . (1999). Detection of genes for periplasmic nitrate reductase in nitrate respiring bacteria and in community DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 177: 263–270.

Francis CA, Roberts KJ, Beman JM, Santoro AE, Oakley BB . (2005). Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14683–14688.

Fuhrman JA . (2009). Microbial community structure and its functional implications. Nature 459: 193–199.

Graham LG, Bond PL, Richardson DJ, Spiro S . (2003). Characterization of a nitrate-respiring bacterial community using the nitrate reductase gene (narG) as a functional marker. Microbiology 149: 229–237.

Graham EB, Wieder WR, Leff JW, Weintraub SR, Townsend AR, Cleveland CC et al. (2014). Do we need to understand microbial communities to predict ecosystem function? A comparison of statistical models of nitrogen cycling processes. Soil Biol Biochem 68: 279–282.

He Z, Gentry TJ, Schadt CW, Wu L, Liebich J, Chong SC et al. (2007). GeoChip: a comprehensive microarray for investigating biogeochemical, ecological and environmental processes. ISME J 1: 67–77.

Heyer J, Galchenko VF, Dunfield PF . (2002). Molecular phylogeny of type II methane-oxidizing bacteria isolated from various environments. Microbiology 148: 2831–2846.

Kang S, Van Nostrand JD, Gough HL, He Z, Hazen TC, Stahl DA et al. (2013). Protein-encoding gene array-based analysis of microbial communities in heavy metals-contaminated lake sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 86: 200–214.

Kloos K, Mergel A, Rösch C, Bothe H . (2001). Denitrification within the genus Azospirillum and other associative bacteria. Funct Plant Biol 28: 991–998.

Könneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA . (2005). Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437: 543–546.

Koricheva J, Gurevitch J, Mengersen K . (2013) Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA.

Liu B, Morkved PT, Frostegard A, Bakken LR . (2010). Denitrification gene pools, transcription and kinetics of NO, N2O and N2 production as affected by soil pH. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 72: 407–417.

Luton PE, Wayne JM, Sharp RJ, Riley PW . (2002). The mcrA gene as an alternative to 16S rRNA in the phylogenetic analysis of methanogen populations in landfill. Microbiology 148: 3521–3530.

Mackelprang R, Waldrop MP, DeAngelis KM, Maude MD, Chavarria KL, Bazewicz SJ et al. (2011). Metagenomic analysis of a permafrost microbial community reveals a rapid response to thaw. Nature 480: 368–371.

Moran MA, Satinsky B, Gifford SM, Luo H, Rivers A, Chan LK et al. (2013). Sizing up metatranscriptomics. ISME J 7: 237–243.

Mueller JG, Devereux R, Santavy DL, Lantz SE, Willis SG, Pritchard PH . (1997). Phylogenetic and physiological comparisons of PAH-degrading bacteria from geographically diverse soils. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 71: 329–343.

Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC . (2007). Effect size, confidence intervals and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 82: 591–605.

Poret-Peterson AT, Graham JE, Gulledge J, Klotz MG . (2008). Transcription of nitrification genes by the methane-oxidizing bacterium, Methylococcus capsulatus strain Bath. ISME J 2: 1213–1220.

Rosenthal R . (1991) Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research. SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA.

Rotthauwe JH, Witzel KP, Liesack W . (1997). The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 4704–4712.

Schimel JP . (1995). Ecosystem consequences of microbial diversity and community structure. In: Chapin FS, Korner C (eds) Arctic and Alpine Biodiversity: Patterns, Causes, and Ecosystem Consequences. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, pp 239–254.

Schimel JP, Bennett J, Fierer N . (2005). Microbial community composition and soil N cycling: is there really a connection? In: Bardgett RD, Hopkins DW, Usher MB (eds) Biological Diversity and Function in Soils. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, pp 171–188.

Shannon EM, Saleh-Lakha S, Burton DL, Zebarth BJ, Goyer C, Trevors JT . (2011). Effect of nitrate and glucose addition on denitrification and nitric oxide reductase (cnorB) gene abundance and mRNA levels in Pseudomonas mandelii inoculated into anoxic soil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 100: 183–195.

Streber WR, Timmis KN, Zenk MH . (1987). Analysis, cloning, and high-level expression of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate monooxygenase gene tfdA of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134. J Bacteriol 169: 2950–2955.

Strous M, Kuenen JG, Jetten MS . (1999). Key physiology of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 3248–3250.

Taroncher-Oldenburg G, Griner EM, Francis CA, Ward BB . (2003). Oligonucleotide microarray for the study of functional gene diversity in the nitrogen cycle in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 1159–1171.

Tyson GW, Chapman J, Hugenholtz P, Allen EE, Ram RJ, Richardson PM et al. (2004). Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 428: 37–43.

Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, Halpern AL, Rusch D, Eisen JA et al. (2004). Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304: 66–74.

Viechtbauer W . (2010). Conducting a meta-analysis in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 36: 1–48.

Wang H, Gunsalus RP . (2000). The nrfA and nirB nitrite reductase operons in Escherichia coli are expressed differently in response to nitrate than to nitrite. J Bacteriol 182: 5813–5822.

Yau S, Lauro FM, Williams TJ, DeMaere MZ, Brown MV, Rich J et al. (2013). Metagenomic insights into strategies of carbon conservation and unusual sulfur biogeochemistry in a hypersaline Antarctic lake. ISME J 7: 1944–1961.

Yun AC, Szalay AA . (1984). Structural genes of dinitrogenase and dinitrogenase reductase are transcribed from two separate promoters in the broad host range cowpea Rhizobium strain Irc78. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 7358–7362.

Zhang L, Offre PR, He J, Verhamme DT, Nicol GW, Prosser JI . (2010). Autotrophic ammonia oxidation by soil thaumarchaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 172–17245.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Powell Center working group for their valuable feedback on previous drafts of this manuscript. This manuscript is a product of the USGS Powell Center working group, ‘The next generation of ecological indicators: defining which microbial properties matter most to ecosystem function and how to measure them’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rocca, J., Hall, E., Lennon, J. et al. Relationships between protein-encoding gene abundance and corresponding process are commonly assumed yet rarely observed. ISME J 9, 1693–1699 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.252

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.252

This article is cited by

-

Soil bacterial community composition and function play roles in soil carbon balance in alpine timberline ecosystems

Journal of Soils and Sediments (2024)

-

Plasma membrane intrinsic protein OsPIP2;6 is involved in root-to-shoot arsenic translocation in rice (Oryza sativa L.)

Plant Cell Reports (2024)

-

Long-Term Pollution Does Not Inhibit Denitrification and DNRA by Adapted Benthic Microbial Communities

Microbial Ecology (2023)

-

Inhibitory effect of nitrogen deposition on soil denitrifying activity in a subtropical forest

Plant and Soil (2023)

-

Arable soil nitrogen dynamics reflect organic inputs via the extended composite phenotype

Nature Food (2022)