Abstract

Microbial community profiling using 16S rRNA gene sequences requires accurate taxonomy assignments. ‘Universal’ primers target conserved sequences and amplify sequences from many taxa, but they provide variable coverage of different environments, and regions of the rRNA gene differ in taxonomic informativeness—especially when high-throughput short-read sequencing technologies (for example, 454 and Illumina) are used. We introduce a new evaluation procedure that provides an improved measure of expected taxonomic precision when classifying environmental sequence reads from a given primer. Applying this measure to thousands of combinations of primers and read lengths, simulating single-ended and paired-end sequencing, reveals that these choices greatly affect taxonomic informativeness. The most informative sequence region may differ by environment, partly due to variable coverage of different environments in reference databases. Using our Rtax method of classifying paired-end reads, we found that paired-end sequencing provides substantial benefit in some environments including human gut, but not in others. Optimal primer choice for short reads totaling 96 nt provides 82–100% of the confident genus classifications available from longer reads.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Variation in 16S ribosomal gene sequences has been used since the mid-1980's to characterize microbial diversity (Stahl et al., 1984). Interest in sequence-based surveys of environmental microbes has exploded in recent years with the availability of sequencing technologies that produce ever-larger data sets at ever-decreasing cost; in particular, the Illumina platform is attractive because of throughput, despite its short reads (Sogin et al., 2006; Lazarevic et al., 2009; Claesson et al., 2010; Caporaso et al., 2011; Degnan and Ochman, 2012). Here, we examine the reliability of assignment of novel sequences to known taxa under thousands of simulated scenarios, varying primer choice, read length and environment.

Previous work on taxonomic classification of environmental 16S rRNA gene sequences has focused on whether reference sequences matching a given query share taxonomic annotations (Jonasson et al., 2002; Desantis et al., 2006; Sogin et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Validations of taxonomic classifiers have typically compared a limited range of primers, read lengths and environments (Sundquist et al., 2007; Huse et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008; Hamp et al., 2009). Reference databases contain many sequences derived from some environments and few associated with others, however (Supplementary Figure S1), leading to substantial variation in classification quality. In addition, the use of ‘leave-one-out’ cross-validation at the sequence level (Sundquist et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008)—where a single sequence with a known annotation is held out from a reference database and classified using the remainder—is problematic: reference sequences matching held-out query sequences are likely to originate from the same sample, because natural environments contain ‘microdiverse’ clusters of closely related strains (Acinas et al., 2004).

We addressed these issues by simulating truncated reads from eight large environmental data sets of near-full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences extracted from GreenGenes (Supplementary Table S1), using pairs of 44 ‘universal’ primers commonly found in the literature (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). These were selected from an initial set of 94 primers by the criterion that each primer had to match at least 40% of the sequences in at least one of the chosen environmental samples. Single-end reads were tested from each primer with all viable amplification partners (794 combinations), and paired-end reads were tested using all 374 viable pairings of the 22 forward and 22 reverse primers. Simulations using 11 read lengths (32 nt, 48 nt, 64 nt, 80 nt, 96 nt, 112 nt, 128 nt, 260 nt, 400 nt, 800 nt and full-length), with the constraint that read length could not exceed amplicon length for each primer pair, produced 6617 single-end and 3061 paired-end datasets per environment.

Reference databases were constructed by holding out each entire study in turn from GreenGenes, clustering the remainder at 99% using UCLUST (Edgar, 2010), and selecting one representative sequence per cluster (see Supplementary Methods for details). Each query fragment was then matched against remaining representative sequences using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010), configured to penalize indels and mismatches equally. Clusters were then selected that matched within 0.5% identity of the best hit (hits <80% identity were disregarded). For paired-end query sequences, our Rtax procedure (Supplementary Methods) selected those reference clusters that matched both reads simultaneously with an average percent identity within 0.5% identity of the maximum. Taxonomic classifications were made at each level by retaining annotations agreeing among >50% of the clusters (including those with no annotation in the denominator); these generally extended at best to the genus level, because the reference database provides few species-level annotations.

Sequences from novel taxa (or sequences that appear novel due to sequencing error or chimerism) clearly cannot be correctly classified; however, such sequences may constitute a substantial proportion of a given sample (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1). The version of GreenGenes that we used excluded taxa (defined by 97% identity) that were unique to a single sample, as one of the several strategies to remove chimeras. These unique sequences were therefore excluded from our query sets. Thus the classification rates we report represent the proportion of non-chimeric, non-unique sequences that can be classified to each rank. If an environmental sample is not similarly filtered before classification, then the classifiable proportion (that is, taken with respect to the total sample) will be correspondingly lower.

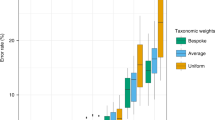

Classification rate and accuracy vary widely among environments and sequence regions, for several reasons: (1) the reference database provides different levels of coverage of each environment, (2) no primer is truly ‘universal’ and different primers (and pairs) hit different proportions of sequences in each environment and (3) the targeted regions are variably informative. Figure 1 shows proportions of sequences from each environment classified to each rank, for all 9678 single-ended and paired-end primer and read length combinations. Horizontal panels compare unfiltered results to classifications passing 80% and 95% estimated accuracy filters (see Supplementary Methods), showing that most classifications can be made with high accuracy when optimal primers are chosen. Remarkably, only 96 nt of sequence (taken as a single read or as a pair of 48 nt reads) can provide 82–100% of the 80% accurate genus classifications available from any read length (Supplementary Table S4). Paired-end sequencing can provide substantial gains in classification rate for some—but not all—environments and read lengths. Paired-end classifications are typically more accurate than those made from single reads, and so are more likely to pass the 95% estimated accuracy filter (Supplementary Table S5). Another surprise is that hypervariable regions need not be specifically targeted, as there is no obvious relationship between taxonomic informativeness of a region and the extent to which it overlaps any of the classical ‘V-regions’.

Classification performance, at three levels of estimated accuracy (Supplementary Methods), of 6617 possible choices of amplification primer, sequencing primer and read length for single-ended reads from different environments (left portion of each panel) and 3061 possible choices of primer pair and read length for paired-end reads (right portion). Combinations of primers and read lengths are sorted on the x axis according to a measure of overall classification performance (Supplementary Methods). Stacked bars show the proportion of non-chimeric, non-unique sequences from each sample—not the proportion of the total sample—that can be classified to each taxonomic level for each combination. See Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1 for the excluded proportion of novel (and thus a priori unclassifiable) sequences in each sample. The top of each colored section indicates how much of the sample can be classified to the given level or better. ‘Primer miss’ (black) indicates sequences that did not match a given primer and so would not be amplified. Classifications more specific than the genus level are exceedingly rare and so are not visible here. Horizontal lines indicate the maximum proportion of each sample classifiable to the genus level using 96 nt or less of sequence (i.e., with an optimal choice of primer or primer pair; see also Supplementary Tables S4 and S5), showing that short reads from the best primers frequently—but not always—provide taxonomic information nearly matching that obtained from longer read lengths. Full-size versions of these panels are available in the supplementary data.

No one combination of primers and read length works best in all environments, but near-optimal performance in six out of the eight environments is available using paired-end 80 nt reads from primers such as E517F, U515F or E341F paired with E1406R or closely related primers (Table 1). However, practical considerations such as ability to amplify low-biomass samples will sometimes influence which primers are used. For instance, short amplicons may be preferred because these are less subject to length heterogeneity biases and chimera formation. Similarly, short single-ended sequences are less subject to errors due to chimeras, simply because they are less likely to span a breakpoint. Classification performance for experimental choices matching such constraints can be found in the supplementary data.

The choice of reference database and taxonomy can have a dramatic impact on the resulting classification accuracy. In this study, we used the current GreenGenes taxonomy, which has been filtered to remove chimeras and where the taxonomic annotations are comprehensive and consistent with the phylogenetic tree (McDonald et al., 2011). Experiments using a previous version of the GreenGenes taxonomy lacking these features yielded far poorer accuracy (data not shown). In addition, bolstering areas of low coverage in reference databases will substantially improve classifier performance. For instance, taxa in the hypersaline mat, coral and grassland soil samples were underrepresented in the reference database (Supplementary Figure S1), and—presumably as a consequence—classifications of sequences from those samples were less likely to prove correct (Figure 1). Additional data sets from poorly sampled environments will also help to distinguish chimeric from legitimate but novel sequences.

In combination, these results indicate that taxonomic classifications of short reads—especially genus-level classifications—should be treated with skepticism, unless the specific combination of primer, read length, environmental source, reference database and assignment method has been thoroughly validated. At the same time, optimal choices of these parameters allow high classification rates and high accuracy. Thus, large-scale projects such as the Earth Microbiome Project (Gilbert et al., 2010), which aims to collect and analyze samples from tens of thousands of microbial habitats around the globe, may reasonably proceed with standardized primer choices and short reads.

References

Acinas SG, Klepac-Ceraj V, Hunt DE, Pharino C, Ceraj I, Distel DL et al. (2004). Fine-scale phylogenetic architecture of a complex bacterial community. Nature 430: 551–554.

Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ et al. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108 (Suppl 1): 4516–4522.

Claesson MJ, Wang Q, O'Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, Cole JR, Ross RP et al. (2010). Comparison of two next-generation sequencing technologies for resolving highly complex microbiota composition using tandem variable 16S rRNA gene regions. Nucleic Acids Res 38: e200.

Desantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 5069–5072.

Degnan PH, Ochman H . (2012). Illumina-based analysis of microbial community diversity. The ISME J 6: 183–194.

Edgar RC . (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461.

Gilbert JA, Meyer F, Antonopoulos D, Balaji P, Brown CT, Brown CT et al. (2010). Meeting report: the terabase metagenomics workshop and the vision of an Earth Microbiome Project. Stand Genomic Sci 3: 243–248.

Hamp TJ, Jones WJ, Fodor AA . (2009). Effects of experimental choices and analysis noise on surveys of the ″rare biosphere″. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 3263–3270.

Huse SM, Dethlefsen L, Huber JA, Welch DM, Relman DA, Sogin ML . (2008). Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet 4: e1000255.

Jonasson J, Olofsson M, Monstein HJ . (2002). Classification, identification and subtyping of bacteria based on pyrosequencing and signature matching of 16S rDNA fragments. APMIS 110: 263–272.

Lazarevic V, Whiteson K, Huse S, Hernandez D, Farinelli L, Osterås M et al. (2009). Metagenomic study of the oral microbiota by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. J Microbiol Methods 79: 266–271.

Liu CH, Lee SM, Vanlare JM, Kasper DL, Mazmanian SK . (2008). Regulation of surface architecture by symbiotic bacteria mediates host colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3951–3956.

McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A et al. (2011). An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J; e-pub ahead of print 1 December 2011; doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.139.

Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, Neal PR et al. (2006). Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored ″rare biosphere″. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12115–12120.

Stahl DA, Lane DJ, Olsen GJ, Pace NR . (1984). Analysis of hydrothermal vent-associated symbionts by ribosomal RNA sequences. Science 224: 409–411.

Sundquist A, Bigdeli S, Jalili R, Druzin ML, Waller S, Pullen KM et al. (2007). Bacterial flora-typing with targeted, chip-based pyrosequencing. BMC Microbiol 7: 108.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . (2007). Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5261–5267.

Wu D, Hartman A, Ward N, Eisen JA . (2008). An automated phylogenetic tree-based small subunit rRNA taxonomy and alignment pipeline (STAP). PLoS One 3: e2566.

Acknowledgements

This research used ShaRCS, UC Shared Research Computing Services Cluster, which is technically supported by multiple UC IT divisions and managed by the University of California, Office of the President. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (HG4872; HG4866; T32 institutional training grant DK00700733) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Soergel, D., Dey, N., Knight, R. et al. Selection of primers for optimal taxonomic classification of environmental 16S rRNA gene sequences. ISME J 6, 1440–1444 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.208

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.208

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptomic Response of Superworm in Facilitating Polyethylene Biodegradation

Journal of Polymers and the Environment (2024)

-

In silico evaluation and selection of the best 16S rRNA gene primers for use in next-generation sequencing to detect oral bacteria and archaea

Microbiome (2023)

-

Evaluation of microbial communities of Chinese Feng-flavor Daqu with effects of environmental factors using traceability analysis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Assessment trial of the effect of enteral insulin on the preterm infant intestinal microbiota

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

Aerial transport of bacteria by dust plumes in the Eastern Mediterranean revealed by complementary rRNA/rRNA-gene sequencing

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)