Abstract

Sirex noctilio is an invasive wood-feeding wasp that threatens the world's commercial and natural pine forests. Successful tree colonization by this insect is contingent on the decline of host defenses and the ability to utilize the woody substrate as a source of energy. We explored its potential association with bacterial symbionts that may assist in nutrient acquisition via plant biomass deconstruction using growth assays, culture-dependent and -independent analysis of bacterial frequency of association and whole-genome analysis. We identified Streptomyces and γ-Proteobacteria that were each associated with 94% and 88% of wasps, respectively. Streptomyces isolates grew on all three cellulose substrates tested and across a range of pH 5.6 to 9. On the basis of whole-genome sequencing, three Streptomyces isolates have some of the highest proportions of genes predicted to encode for carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZyme) of sequenced Actinobacteria. γ-Proteobacteria isolates grew on a cellulose derivative and a structurally diverse substrate, ammonia fiber explosion-treated corn stover, but not on microcrystalline cellulose. Analysis of the genome of a Pantoea isolate detected genes putatively encoding for CAZymes, the majority predicted to be active on hemicellulose and more simple sugars. We propose that a consortium of microorganisms, including the described bacteria and the fungal symbiont Amylostereum areolatum, has complementary functions for degrading woody substrates and that such degradation may assist in nutrient acquisition by S. noctilio, thus contributing to its ability to be established in forested habitats worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transcontinental movement during human trade and travel is resulting in increased rates of biological invasions (Haack, 2001). Annual economic losses from exotic forest and wood-boring insects in the United States are estimated at $3.1 billion USD (Pimentel et al., 2005). Bark- and wood-boring species are overrepresented among invading species owing to their cryptic nature (living within woody tissues), associations with dead plants and stored products in their native range, and nutrient-poor feeding substrate that lengthens the development time and hence facilitates long distance transport. Once established in a new region, these insects often encounter trees lacking coevolved defenses, and hence exert wide-scale mortality (Gandhi and Herms, 2009).

The environmental and economic damage caused by invasive bark- and wood-boring insects can easily distract from our appreciation of the severe obstacles they encounter, particularly the utilization of recalcitrant cellulose as an energy source. Symbioses with cellulose-degrading microorganisms appear to compensate for an inability to produce cellulases in many insects (Martin, 1991; Douglas, 2009) and these associations, whether obligate or facultative, are important drivers in the evolution of wood-feeding insects (Veivers et al., 1983). This group includes prominent invasive pests, such as the wood-boring emerald ash borer, and Formosan termite, among others, which harbors gut microorganisms that contribute to insect nutrition through degradation of cellulose (Delalibera et al., 2005; Warnecke et al., 2007; Vasanthakumar et al., 2008), hemicellulose (Brennan et al., 2004) and lignin (Pasti et al., 1990; Geib et al., 2008).

Bacteria are most frequently implicated in facilitating cellulose degradation in insects. For example, Actinobacteria associated with termites assist in nutrient acquisition from a diversity of polysaccharides including cellulose (Pasti and Belli, 1985; Watanabe et al., 2003) and hemicelluloses (Schäfer et al., 1996). Proteobacteria associated with insects are also involved in carbohydrate degradation (Delalibera et al., 2005), and can be involved in provisioning other nutrients such as amino acids (Moran and Baumann, 2000) and nitrogen (Pinto-Thomás et al., 2009).

Sirex noctilio Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Siricidae) is a tree-killing insect native to Eurasia and northern Africa that has become established in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, South America, China and, most recently, North America (Wingfield et al., 2001; Hoebeke et al., 2005). It is a major threat to commercial and natural pine forests (Carnegie et al., 2006). Siricid woodwasps are tightly associated with Amylostereum fungi that are vectored by female wasps within specialized mycangia, located internally at the base of the ovipositor (Slippers et al., 2003). S. noctilio kills host trees by injecting a combination of a phytotoxic mucus and symbiotic fungus, Amylostereum areolatum (Fr.) Boidin, into the sapwood during oviposition (Coutts, 1969a, 1969b). This both reduces host defenses (Coutts, 1969a, 1969b) and provides nutrients for the developing brood. Amylostereum fungi produce cellulases that are ingested by feeding larvae, and thus facilitate nutrient acquisition via cellulose degradation (Kukor and Martin, 1983). In addition, these fungi likely supplement sterols to the larval diet as has been found in other insect–fungal symbioses (Kok et al., 1970; Bentz and Six, 2006). Although the association of S. noctilio with A. areolatum is relatively well understood, the identities and potential roles of bacteria associated with S. noctilio are unknown. Given that symbioses involving fungi or bacteria are considered key drivers in the diversification and success of animals (Zilber-Rosenberg and Rosenberg, 2008) and particularly insects (Klepzig et al., 2009), we posit that bacteria associated with S. noctilio are having a similar role.

We characterized bacteria associated with S. noctilio that degrade cellulose and its derivatives. Bacteria isolated from larvae and adults were grown on the cellulose derivative carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) to select isolates with cellulolytic potential. Growth and enzymatic activity of isolated bacteria were assessed on several substrates, including CMC, ammonia fiber explosion-treated corn stover (Teymouri et al., 2004) and microcrystalline cellulose. To further characterize the potential of these isolates to degrade cellulose and other carbohydrates, we analyzed the genomes of four bacteria including three of the strongest degraders of CMC in the genus Streptomyces and one moderate degrader, a γ-Proteobacteria in the genus Pantoea, for genes encoding for the production of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Last, we estimated the frequency of association of these bacteria from a population in the United States by screening adult females using denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and culturing methods. The findings presented here will assist in understanding the roles of these bacteria in the nutritional ecology and invasive success of S. noctilio.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and bacterial isolation

S. noctilio were collected from infested scots pine, Pinus sylvestris L, in Onondaga County, NY, USA in 2008 and Oswego County, NY, USA in 2009. Because of aggressive management of S. noctilio, multiple populations for sampling were not available. Naturally infested trees were cut and transported to the USDA APHIS PPQ Pest Survey, Detection, and Exclusion Lab in Syracuse, NY, USA as described by Zylstra et al. (2010). Wasps emerged in the lab and were collected for use. Microbial isolates were obtained from four adult females and six larvae collected in 2008, and were screened for cellulase activity. All insects were surface sterilized in 95% ethanol for 1 min and rinsed twice in sterile 1 × phosphate-buffered solution. To isolate the symbiotic fungus A. areolatum, mycangia of adults were dissected and plated onto potato dextrose agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA). Larval guts and adult ovipositors and mycangia were removed surgically. These organs and the body were ground separately in 1 ml of 1 × phosphate-buffered solution using a sterilized mortar and pestle, and were plated onto four media to target an increased diversity of bacterial taxa: yeast and malt extract agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company), acidified yeast malt extract agar (for gut dissections only), tryptic soy agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company) and agar supplemented with chitin (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). Petri dishes were stored at room temperature in darkness for at least 3 days until visible colonies formed, except for those with chitin agar, which were stored for at least 1 month. Bacteria with unique morphologies and one A. areolatum isolate were screened for the production of cellulolytic enzymes following a standard CMC assay (Teather and Wood, 1982). Isolates that tested positive were then grown on CMC, ammonia fiber explosion-treated corn stover at three different pH levels (5.6, 7.0 and 9.0) and microcrystalline cellulose to assess growth and degradation ability.

To estimate the frequency of association of these bacterial taxa with S. noctilio, 36 adult wasps collected in 2009 were analyzed as follows. Insects were surface sterilized and the mycangia were surgically removed and plated onto potato dextrose agar. The remaining body was ground in phosphate-buffered solution, and 50 μl of each sample was spread onto agar supplemented with chitin to target the isolation of Actinobacteria. Additional culture-independent analysis of these samples is described below.

16S rRNA sequencing and analysis

DNA was extracted (see Supplementary Materials and methods) from isolates that degraded CMC and from Streptomyces isolated from wasps collected in 2009. The V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene was then amplified as previously described (Holben et al., 2002) and sequenced (University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center, Madison, WI, USA). Phylogenetic trees of isolate sequences were created with Bionumerics software (Applied Maths Inc., Austin, TX, USA) using the neighbor-joining method with Jukes and Cantor correction.

To assess the frequency of association of taxa closely related to CMC-degrading isolates, DGGE was performed as described by Feris et al. (2003). Briefly, DNA was extracted from 34 of the 36 wasps collected in 2009. DNA from wasps and from 12 cultures, selected to represent the diversity of the isolates, was amplified using clamped primers and DGGE was performed (see Supplementary Materials and Methods). Isolate profiles were then compared with insect bacterial community profiles using the band-matching function of Bionumerics software. Isolates with different band migration lengths were classified as different operational taxonomic units. Insect bacterial community profiles determined by Bionumerics software to contain a band that migrated to the same length as an isolate were determined to be associated with the same operational taxonomic units as the isolate.

Whole-genome sequencing

Draft genomes for Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actF, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actG and Pantoea sp. SL1_M5 were sequenced at the Joint Genome Institute using 454 pyrosequencing (Margulies et al., 2005), except for Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, which included Illumina sequencing (Bennett, 2004). All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the Joint Genome Institute can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/. The draft genome sequences for Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actF, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actG and Pantoea sp. SL1_M5 are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers NZ_ADFD00000000, ADXB00000000, ADXA00000000 and X (NCBI project #49341), respectively.

Carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) assignment of genome sequences and analysis

To annotate each draft genome, Prodigal (http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/; Hyatt et al., 2010) was used to predict open reading frames from all generated contigs. The translated proteins from all open reading frames of each genome were annotated using the CAZyme database (Cantarel et al., 2008).

To compare the protein-coding sequences of the draft genomes of S. noctilio-associated Streptomyces isolates with other Actinobacteria, CAZyme annotations were assigned to the predicted proteome of all sequenced Actinobacteria in the current prokaryotic genome collection (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi, accessed on 15 March 2010). The proportion of each organism’s proteome devoted to CAZyme production was determined by dividing the total number of putative CAZymes by the total predicted proteome, and expressing this value as a percentage.

Further details regarding bacterial isolation, DGGE, DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing and growth bioassays are provided online in the Materials and Methods in the Supplementary Information.

Results

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene from isolates that displayed positive activity on CMC identified members of the γ-Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria (Figure 1). Phylogenetic analysis of γ-Proteobacteria isolates revealed bacteria closely related to that in the genera Enterobacter, Kluyvera, Leclercia, Pantoea, Rahnella and Serratia (Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Table S1). All Actinobacteria isolates belong to the genus Streptomyces (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree and frequency of association of cellulose-degrading bacteria associated with S. noctilio. The out-group Burkholderia multivorans and closely related type strains (denoted ‘T’) are included, as determined by the Ribosomal Database Project (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu). Frequency of association of CMC-degrading taxa detected by DGGE and pooled class-level phylogenetic determination is represented by the pie charts (percentage of wasps associated with corresponding taxa in black; percentage of wasps with taxa not detected in white). Frequency of association was determined by DGGE, except when culturing was used (labeled ‘C’). Inset: number of cellulose-degrading taxa detected from individual wasps. 1−5Enterobacteriales isolates used to estimate frequency of association using DGGE. Common numerals were indistinguishable. †Isolates from which draft genomes were analyzed.

On the basis of DGGE analysis of isolate rRNA, we identified six distinguishable CMC-degrading taxa (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S3). Each of 34 wasps was associated with at least one bacterial taxon that was likewise indistinguishable from one of the CMC-degrading isolates, and 60% of wasps were associated with three such taxa (insert in Figure 1). Streptomyces bacteria were associated with 94% of wasps (Figure 1), as determined by a combination of culturing (21 of 36 wasps; Supplementary Table S3) and DGGE (31 of 34 wasps). γ-Proteobacteria were associated with 88% of wasps (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S3). Within the γ-Proteobacteria, 79% of wasps were associated with bacteria that were indistinguishable by DGGE from isolates SL1_M5 and SL4_G15 that are closely related to Pantoea and Enterobacter, respectively; 47% with bacteria indistinguishable from isolate SL4_G10 that is closely related to an unclassified bacterium in Enterobacteriaceae (clusters with isolate SL4_G10 (Figure 1) that is closely related to Leclercia adecarboxylata); 26% with bacteria indistinguishable from isolates SL1_YG9, SL4_YG8 and SL3_YG14 that are closely related to Rahnella and Serratia quinivorans; 9% with bacteria indistinguishable from isolates SL1_YG4 and SL1_G12 that are both closely related to Pantoea cedenensis and 6% with bacteria indistinguishable from isolate SL1_M3 that is closely related to an unclassified bacterium in Enterobacteriaceae.

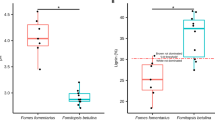

To further test the cellulolytic-degrading capacity of the bacterial isolates, we performed growth assays on three substrates: repeating with CMC, microcrystalline cellulose and corn stover. Because CMC is a derivative vulnerable to degradation by enzymes that are not necessarily active on more recalcitrant forms of cellulose, including both a pure and diverse cellulose-rich substrate provides a more stringent test of enzymatic ability. Streptomyces isolates had the greatest CMC degradation index of all bacteria (Figure 2). All of these had values above that of the fungal symbiont of S. noctilio, A. areolatum (Figure 2). Growth of all Streptomyces isolates in microcrystalline cellulose and water resulted in a visible change in the texture and settling of the cellulose, and subsequent enzyme activity of the supernatant was detected on CMC (Figure 2). In contrast, none of the γ-Proteobacteria grew in microcrystalline cellulose, and no enzymatic activity of the supernatant was detected on CMC. Most isolates, including γ-Proteobacteria, grew on corn stover at pH 7.0, whereas only Streptomyces isolates grew on corn stover across the tested pH range, with the exception of two isolates that did not grow at pH 9.0 (Figure 2).

Summary of bacterial performance on cellulolytic substrates, including degradation of CMC, growth on corn stover and cellulolytic enzyme production after growing on microcrystalline cellulose. Growth and enzymatic activity are categorically ranked, with no label corresponding to no activity, (+) detectable, (++) moderate and (+++) strong activity. Label in parentheses represents presence (+) or absence (−) of degradation of CMC from culture growing in the absence of microcrystalline cellulose. 1Fungus.

To assess the full potential for carbohydrate degradation by bacteria associated with S. noctilio, we sequenced the genomes of four isolates to draft quality (Table 1). These included three Streptomyces that were both frequently associated with S. noctilio and proficient at growing on cellulose, and one Pantoea that was bioactive on CMC. We identified the predicted glycoside hydrolase (GH) families of CAZymes encoded within the genomes of isolates Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actF, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actG and Pantoea sp. SL1_M5. The genomes of Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, SA3_actF and SA3_actG contain 75, 69 and 77 putative genes, respectively, from across 25, 29 and 30 GH families, respectively (Table 2). Among these are genes from three groups of enzymes involved in cellulose deconstruction, which are present in all three Streptomyces isolates: endo-1,4-β-glucanases from families GH5, GH6, GH12, GH16 and GH48; exo-1,4-β-glucanases from families GH1 and GH3; and 1,4-β-glucosidases from families GH1, GH3 and GH31 (Table 2). Also, of note is the presence of genes from families GH19, GH46 and GH75, which may be involved in deconstructing chitin, a carbohydrate structurally similar to cellulose. The genome of Pantoea sp. SL1_M5 contains 28 genes from 16 GH families, including one gene encoding for a putative cellulase from GH8, a family that was not detected in the Streptomyces genomes. However, other genes present in the genome of Pantoea sp. SL1_M5 that may contribute to cellulose deconstruction include that encoding for exo-1,4-β-glucanases and 1,4-β-glucosidases from families GH1, GH3 and GH31.

Genes encoding for putative hemicellulases were also detected in all three Streptomyces genomes, including families GH1-GH3, GH5, GH10, GH11, GH13, GH15, GH26, GH27, GH30, GH38, GH39, GH76 and GH78 (Table 2). Interestingly, Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE appears to have a different hemicellulase profile than Streptomyces sp. SA3_actF and SA3_actG. For example, putative enzymes detected in SA3_actF and SA3_actG that were not detected in SA3_actE include mannanases (GH26 and GH76), manosidases (GH38) and xylosidases (GH39). In contrast, putative enzymes detected in SA3_actE that were absent in SA3_actF and SA3_actG include rhamnosidases (GH78), xylanases (GH10 and GH11) and galactosidases (GH42). Even with these differences, genes coding for enzymes in the GH13 family were the most frequent of the CAZyme genes detected across all Streptomyces draft genomes. Genes encoding for putative hemicellulases from families GH1–GH3 and GH42 were detected in Pantoea sp. SL1_M5, and each was also detected in at least one of the Streptomyces genomes. One family detected in Pantoea sp. SL1_M5 but not detected in any Streptomyces isolates was GH37, which is putatively involved in deconstruction of the disaccharide α,α-trehalose.

Other CAZymes detected include carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM), carbohydrate esterases (CE) and polysaccharide lyases (Supplementary Table S4). Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE has 47 genes within 11 CBM families, many of which are involved in binding with hemicellulose (CBM2, CBM13 and CBM16) and cellulose (CBM2, CBM6 and CBM16). Streptomyces sp. SA3_actF and SA3_actG have 31 and 34 CMB genes, respectively, all from within 10 families also common with SA3_actE. One CBM was detected in Pantoea sp. SL1_M5, CBM50. This module is involved in binding to GH enzymes from families such as GH18, GH19 and GH25 that were detected in Streptomyces isolates, and from families such as GH19, GH24 and GH73 that were detected in Pantoea sp. SL1_M5. Hemicellulose-active esterases and lyases were also detected in Streptomyces isolates, and were more prevalent with SA3_actE than the other two isolates. Some of the families included enzymes active on xylan (CE4) and pectin (CE8 and polysaccharide lyase 1). Two genes from two CE families were detected in Pantoea sp. SL1_M5, including CE4, that was detected, and CE11, that was not detected, in Streptomyces genomes.

To assess the relative potential of carbohydrate degradation of Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE, SA3_actF and SA3_actG, we performed a comparative genomics analysis using the sequenced genomes of all other Actinobacteria. This revealed that all three S. noctilio-associated Streptomyces isolates have exceptionally high proportions of their genomes devoted to CAZyme production. Streptomyces sp. SA3_actE in particular has 1.92% of its predicted proteome devoted to CAZyme production, which is ranked as the sixth highest of nearly 100 sequenced actinobacterial genomes (Supplementary Table S5). Streptomyces sp. SA3_actG and SA3_actF each have 1.70% and 1.47% of their predicted proteomes devoted to CAZyme production, and are ranked thirteenth and nineteenth among the sequenced Actinobacteria, respectively (Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

Multiple taxa of bacteria were isolated from S. noctilio, of which Streptomyces were most frequently associated and showed high potential to degrade a variety of cellulose substrates. Cellulose-degrading Streptomyces spp. have been found to be associated with other wood-feeding insects, such as termites (Pasti and Belli, 1985; Watanabe et al., 2003), bark beetles (Scott et al., 2008) and wood-boring beetles (Vasanthakumar et al., 2008). A combination of enzymes is required to convert cellulose into glucose monomers (Ghose, 1977), and the Streptomyces isolates sequenced in this study contain genes that putatively encode for each of these enzymes. Endoglucanases such as endo-1,4-β-glucanase cleave β(1,4)-glucosidic linkages, thereby making the non-reducing ends of individual cellulose strands available for cleavage by exoglucanases such as exo-1,4-β-glucanase. The resulting cellobiose and water-soluble cellodextrins such as CMC are then cleaved by β-glucosidase. The activity of the S. noctilio-associated Streptomyces on CMC and microcrystalline cellulose, in combination with the putative CAZymes detected in their genomes, strongly suggests that these bacteria have the capacity to convert cellulose to simple sugars assessable to S. noctilio. Similar enzymatic activity has been shown by other Streptomyces spp. isolated from soil (Semêdo et al., 2000).

γ-Proteobacteria associated with S. noctilio displayed limited growth on CMC and corn stover, and no enzymatic activity on microcrystalline cellulose. CMC is a water-soluble cellodextrin vulnerable to hydrolysis by β-glucosidases among other enzymes; however, β-glucosidases are not active on cellulose (Reese, 1957). Ammonia fiber explosion-treated corn stover is pre-treated to burst cellulose fibers, thereby decrystallizing the cellulose and releasing fibers from lignin and hemicellulose. This treatment increases the degradability of the substrate (Teymouri et al., 2004), resulting in residual ammonia and available starches that may support microbial growth. Thus, the observed enzymatic activity of the γ-Proteobacteria is characteristic of β-glucosidases. β-Glucosidase production is predicted by the presence of several genes in the genome of Pantoea sp. SL1_M5. Although one putative cellulase in the GH8 family was predicted in the genome of Pantoea sp. SL1_M5, γ-Proteobacteria appear better equipped to deconstruct hemicelluloses, an activity common among gut bacteria of other insects (Brennan et al., 2004; Warnecke et al., 2007).

Environmental pH is an important determinant of enzyme production (Semêdo et al., 2000) and adsorption (Kim et al., 1998), and activity of these isolates at different pH levels may provide some insight into their activity in association with S. noctilio. The pH of wood-boring hymenopteran guts is unknown, but other wood-boring insects that likewise house γ-Proteobacteria and Streptomyes have neutral guts (Balogun, 1969; Kukor and Martin, 1980). This is consistent with our observation that most S. noctilio associates grew on corn stover at neutral pH. Streptomyces isolates also grew on corn stover at pH 5.6 and 9.0, which suggest an ability to grow in a diversity of insect-associated environments, such as frass and galleries. The capillary liquids of fir, spruce and poplar are near pH 6.0 (Schmidt, 1986), and colonization of frass and insect galleries by other bacteria has been shown (Dillon et al., 2002; Scott et al., 2008). If bacteria colonize woody substrates ingested by S. noctilio larvae, utilization of predigested materials or enzymes would benefit development, similar to the hypothesized model for the fungal mutualist A. areolatum (Kukor and Martin, 1983). The presence of genes encoding for chitinase production in Streptomyces associated with S. noctilio is intriguing, and suggests that these bacteria might assist in degrading the hyphae of the wasp's fungal symbionts.

Streptomyces associated with S. noctilio were efficient in degrading many forms of cellulose, and γ-Proteobacteria degraded more enzymatically vulnerable carbohydrates such as starches and hemicellulose. Such enzymatic activity by bacterial associates may contribute to the ability of S. noctilio to utilize multiple host species throughout broad regions of the world. In this population in the United States, both Streptomyces spp. and γ-Proteobacteria are associated with a high percentage of S. noctilio adults. Analysis of cellulose-degrading bacteria associated with Sirex worldwide will provide insight into the ecological roles of these bacteria. For example, bacterial communities associated with the bark beetle Dendroctonus valens LeConte showed geographic structure across much of its range, with similarities related to the distance between host populations (Adams et al., 2010). In another phloem-feeding beetle, the invasive emerald ash borer, members of both Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria were found to degrade the cellulose derivative CMC (Vasanthakumar et al., 2008).

Success of S. noctilio, as well as other wood-feeding insects, depends on the ability to convert the plant cell wall into more accessible forms of energy. Because this process requires multiple enzymes because of the complex structure of plant cell walls, a consortium of organisms may be best suited for decomposition of cellulose-rich substrates (Ohkuma and Kudo, 1996; Schlüter et al., 2008; Strickland et al., 2009). We detected bacteria associated with S. noctilio that can degrade a diversity of carbohydrates, including cellulose and putatively hemicellulose. Cellulose degradation by Amylostereum chailletii (Pers.: Fr.) Boidin, the fungal symbiont of S. cyaneus Fabricius, has been previously suggested on the basis of the recovery of fungal-produced cellulases in the insect gut (Kukor and Martin, 1983). Complementary enzymatic activity between fungi and bacteria has been suggested for the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants (Suen et al., 2010). We propose that bacterial and fungal symbionts of S. noctilio have complementary roles in terms of specific enzymatic activities, spatial context or both.

Accession codes

References

Adams AS, Adams SM, Currie CR, Gillette NE, Raffa KF . (2010). Geographic variation in bacterial communities associated with the red turpentine beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ Entomol 39: 406–414.

Balogun RA . (1969). Digestive enzymes of the alimentary canal of the larch bark beetle Ips cembrae Heer. Comp Biochem Physiol 29: 1267–1270.

Bennett S . (2004). Solexa Ltd. Pharmacogenomics 5: 433–438.

Bentz BJ, Six DL . (2006). Ergosterol content of three fungal species associated with Dendroctonus ponderosae and D. rufipennis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Scolytinae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 99: 189–194.

Brennan YL, Callen WN, Christoffersen L, Dupree P, Goubet F, Healey S et al. (2004). Unusual microbial xylanases from insect guts. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 3609–3617.

Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B . (2008). The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D233–D238.

Carnegie AJ, Matsuki M, Haugen DA, Hurley BP, Ahumada R, Klasmer P et al. (2006). Predicting the potential distribution of Sirex noctilio (Hymenoptera: Siricidae), a significant exotic pest of Pinus plantations. Ann For Sci 63: 119–128.

Coutts MP . (1969a). The mechanism of pathogenicity of Sirex noctilio on Pinus radiata. I. Effects of the symbiotic fungus Amylostereum sp. (Thelophoraceae). Aust J Biol Sci 22: 915–924.

Coutts MP . (1969b). The mechanism of pathogenicity of Sirex noctilio of Pinus radiata. II. Effects of S. noctilio mucus. Aust J Biol Sci 22: 1153–1161.

Delalibera Jr I, Handelsman J, Raffa KF . (2005). Contrasts in cellulolytic activities of gut microorganisms between the wood borer, Saperda vestita (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the bark beetles, Ips pini and Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ Entomol 34: 541–547.

Dillon RJ, Vennard CT, Charnley AK . (2002). A note: gut bacteria produce components of a locust cohesion pheromone. J Appl Microbiol 92: 759–763.

Douglas AE . (2009). The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct Ecol 23: 38–47.

Feris KP, Ramsey PW, Frazar C, Rillig MC, Gannon JE, Holben WE . (2003). Structure and seasonal dynamics of hyporheic zone microbial communities in free-stone rivers of the western United States. Microb Ecol 46: 200–215.

Gandhi KJ, Herms DA . (2009). Direct and indirect effects of invasive exotic insect herbivores on ecological processes and interactions in forests of eastern North America. Biol Invasions 12: 389–405.

Geib SM, Filley TR, Hatcher PG, Hoover K, Carlson JE, Jimenez-Gasco M et al. (2008). Lignin degradation in wood-feeding insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 12932–12937.

Ghose TK . (1977). Cellulase biosynthesis and hydrolysis of cellulosic substances. Adv Biochem Eng 6: 39–76.

Haack RA . (2001). Intercepted Scolytidae (Coleoptera) at US ports of entry: 1985–2000. Integr Pest Manage Rev 6: 253–282.

Hoebeke RE, Haugen DA, Haack RA . (2005). Sirex noctilio: discovery of a Palearctic siricid woodwasp in New York. News Mich Entomol Soc 50: 24–25.

Holben WE, Williams P, Saarinen M, Särkilahti LK, Apajalahti JHA . (2002). Phylogenetic analysis of intestinal microflora indicates a novel mycoplasma phylotype in farmed and wild salmon. Microb Ecol 44: 175–185.

Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ . (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 119.

Kim DW, Yang JH, Jeong YK . (1998). Adsorption of cellulose from Trichoderma viride on microcrystalline cellulose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 28: 148–154.

Klepzig KD, Adams AS, Handelsman J, Raffa KF . (2009). Symbiosis: a key driver of insect physiological processes, ecological interactions, evolutionary diversification, and impacts on humans. Environ Entomol 38: 67–77.

Kok LT, Norris DM, Chu HM . (1970). Sterol metabolism as a basis for a mutualistic symbiosis. Nature 225: 661–662.

Kukor JJ, Martin MM . (1980). The transformation of Saperda calcarata (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) into a cellulose digester through the inclusion of fungal enzymes in its diet. Oecologia 71: 138–141.

Kukor JJ, Martin MM . (1983). Acquisition of digestive enzymes by siricid woodwasps from their fungal symbiont. Science 220: 11661–11663.

Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA et al. (2005). Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437: 376–380.

Martin MM . (1991). The evolution of cellulose digestion in insects. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 333: 281–288.

Moran NA, Baumann P . (2000). Bacterial endosymbionts in animals. Curr Opin Microbiol 3: 270–275.

Ohkuma M, Kudo T . (1996). Phylogenetic diversity of the intestinal bacterial community in the termite Reticulitermes speratus. Appl Environ Microbiol 62: 461–468.

Pasti MB, Belli ML . (1985). Cellulolytic activity of actinomycetes isolated from termites (Termitidae) gut. FEMS Microbiol Lett 26: 107–112.

Pasti MB, Pometto III AL, Nuti DL, Crawford DL . (1990). Lignin-solubilizing ability of actinomycetes isolated from termite (Termitidae) gut. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 2213–2218.

Pimentel D, Zuniga R, Morrison D . (2005). Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol Econ 52: 273–288.

Pinto-Thomás A, Anderson MA, Suen G, Stevenson DM, Chu FST, Cleland WW et al. (2009). Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants. Science 326: 1120–1123.

Reese ET . (1957). Biological degradation of cellulose derivatives. Ind Eng Chem 49: 89–93.

Schäfer A, Konrad R, Kuhnigk T, Kämpfer P, Hertel H, König H . (1996). Hemicellulose-degrading bacteria and yeasts from the termite gut. J Appl Microbiol 80: 471–478.

Schlüter A, Bekel T, Diaz NN, Dondrup M, Eichenlaub R, Gartemann KH et al. (2008). The metagenome of a biogas-producing microbial community of a production-scale biogas plant fermenter analyzed by the 454-pyrosequencing technology. J Biotechnol 136: 77–90.

Schmidt O . (1986). Investigations on the influence of wood-inhabiting bacteria on the pH-value in trees. J For Path 16: 181–189.

Scott JJ, Oh D, Yuceer MC, Klepzig KD, Clardy J, Currie CC . (2008). Bacterial protection of beetle-fungus mutualism. Science 322: 63.

Semêdo L, Gomes RC, Bon EP, Soares RM, Linhares LF, Coelho RR . (2000). Endocellulase and exocellulase activities of two Streptomyces strains isolated from a forest soil. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 84: 267–276.

Slippers B, Coutinho TA, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ . (2003). A review of the genus Amylostereum and its association with woodwasps. S Afr J Sci 99: 70–74.

Strickland MS, Osburn E, Lauber C, Fierer N, Bradford MA . (2009). Litter quality is in the eye of the beholder: initial decomposition rates as a function of inoculum characteristics. Func Ecol 23: 627–636.

Suen G, Scott JJ, Aylward FO, Adams SM, Tringe SG, Pinto-Thomás A et al. (2010). An insect herbivore microbiome with high plant biomass-degrading capacity. PLoS Genet 6: e1001129.

Teather RM, Wood PJ . (1982). Use of congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol 43: 777–780.

Teymouri F, Laureano-Pérez L, Alizadeh H, Dale BE . (2004). Ammonia fiber explosion treatment of corn stover. Appl Biochem Biotech 115: 951–963.

Vasanthakumar A, Handelsman J, Schloss PD, Bauer LS, Raffa KF . (2008). Gut microbiota of an invasive subcortical beetle, Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, across various life stages. Environ Entomol 37: 1344–1353.

Veivers PC, O’Brien RW, Slaytor M . (1983). Selective defaunation of Mastotermes darwiniensis and its effect on cellulose and starch metabolism. Insect Biochem 12: 35–40.

Warnecke F, Luginbühl P, Ivanova N, Ghassemian M, Richardson TH, Stege JT et al. (2007). Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450: 560–565.

Watanabe Y, Shinzato N, Fukatsu T . (2003). Isolation of actinomycetes from termites’ guts. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67: 1797–1801.

Wingfield MJ, Slippers B, Roux J, Wingfield BD . (2001). Worldwide movement of exotic forest fungi, especially in the tropics and the southern hemisphere. BioScience 51: 134–140.

Zilber-Rosenberg I, Rosenberg E . (2008). Role of microorganisms in the evolution of animals and plants: the hologenome theory of evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32: 723–735.

Zylstra KE, Dodds KJ, Francese JA, Mastro V . (2010). Sirex noctilio in North America: the effect of stem-injection timing on the attractiveness and suitability of trap trees. Agric For Entomol 12: 243–250.

Acknowledgements

We thank J Tumlinson, K Zylstra, M Crawford and K Boroczky for providing insects, and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center's Biomass Pretreatment Lab for providing ammonia fiber explosion-treated corn stover. D Coyle and anonymous reviewers provided editorial comments that improved the manuscript. We are also indebted to T Woyke for her assistance in whole-genome sequencing. This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the National Science Foundation (MCB-0702025), the USDA NRI (2008-02438) and the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE Office of Science BER DE-FC02-07ER64494). The work conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, A., Jordan, M., Adams, S. et al. Cellulose-degrading bacteria associated with the invasive woodwasp Sirex noctilio. ISME J 5, 1323–1331 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.14

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microbiota and functional analyses of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in root-knot nematode parasitism of plants

Microbiome (2023)

-

The pivotal roles of gut microbiota in insect plant interactions for sustainable pest management

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2023)

-

Bacterial community succession in aerobic-anaerobic-coupled and aerobic composting with mown hay affected C and N losses

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Screening and identification of cellulose-degrading bacteria from soil and leaves at Kerman province, Iran

Archives of Microbiology (2022)

-

Gut microbial communities associated with phenotypically divergent populations of the striped stem borer Chilo suppressalis (Walker, 1863)

Scientific Reports (2021)