Abstract

Soils collected across a long-term liming experiment (pH 4.0–8.3), in which variation in factors other than pH have been minimized, were used to investigate the direct influence of pH on the abundance and composition of the two major soil microbial taxa, fungi and bacteria. We hypothesized that bacterial communities would be more strongly influenced by pH than fungal communities. To determine the relative abundance of bacteria and fungi, we used quantitative PCR (qPCR), and to analyze the composition and diversity of the bacterial and fungal communities, we used a bar-coded pyrosequencing technique. Both the relative abundance and diversity of bacteria were positively related to pH, the latter nearly doubling between pH 4 and 8. In contrast, the relative abundance of fungi was unaffected by pH and fungal diversity was only weakly related with pH. The composition of the bacterial communities was closely defined by soil pH; there was as much variability in bacterial community composition across the 180-m distance of this liming experiment as across soils collected from a wide range of biomes in North and South America, emphasizing the dominance of pH in structuring bacterial communities. The apparent direct influence of pH on bacterial community composition is probably due to the narrow pH ranges for optimal growth of bacteria. Fungal community composition was less strongly affected by pH, which is consistent with pure culture studies, demonstrating that fungi generally exhibit wider pH ranges for optimal growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental factors controlling the distribution and abundance of plants and animals across terrestrial biomes have been studied for centuries, but the environmental factors controlling the distribution and abundance of soil microorganisms are still poorly understood. Recent study conducted using a variety of molecular or biochemical approaches has started to explore the distributional patterns exhibited by soil microbial communities and the biotic or abiotic factors driving these patterns. However, much of this previous study has been conducted using techniques that do not permit detailed and comprehensive phylogenetic or taxonomic surveys of microbial communities (for example, DNA fingerprinting-based approaches, (Fierer and Jackson, 2006), phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analyses, (Bååth and Anderson, 2003). Similarly, much of this previous study has focused on the distribution patterns exhibited by single taxonomic groups, for example, Acidobacteria, (Jones et al., 2009, fungi: Bennett et al. (2009) and Buée et al. (2009), or SR1 bacteria: Davis et al. (2009)), making it difficult to directly compare the patterns exhibited by common microorganisms.

Recent study has demonstrated that changes in soil microbial communities across space are often strongly correlated with differences in soil chemistry (Frey et al., 2004; Nilsson et al., 2007; Lauber et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2009). In particular, it has been shown that the composition, and in some cases diversity, of soil bacterial communities is often strongly correlated with soil pH (Fierer and Jackson, 2006; Hartman et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2009; Lauber et al., 2009). This pattern holds both for overall bacterial community composition (Fierer and Jackson, 2006; Baker et al., 2009; Lauber et al., 2009) and for the composition of individual bacterial groups (Nicol et al., 2008; Davis et al., 2009; Jenkins et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2009). It also seems to hold across a variety of spatial scales, including continental scales (Fierer and Jackson, 2006; Lauber et al., 2009), across land-use types at a given location (Lauber et al., 2008; Jenkins et al., 2009), and across small, submeter scales (Baker et al., 2009; Philippot et al., 2009). However, one limitation of these observational studies is that it is impossible to determine whether the communities are structured directly or indirectly by pH. In other words, we do not know whether pH itself is the factor shaping these communities, or whether pH may be indirectly related to the observed community changes through many environmental factors (for example, nutrient availability, organic C characteristics, soil moisture regime and vegetation type), which often co-vary with changes in soil pH. Similarly, we do not know whether soil pH is also correlated with the community composition of fungi, another dominant microbial group in soil. There is some indication that the spatial patterns exhibited by soil fungal communities are not correlated, or less strongly correlated, with soil pH than has been observed for bacterial communities (for example, Lauber et al., 2008). However, the paucity of detailed studies directly comparing the spatial patterns exhibited by soil bacteria and fungi make it difficult to draw any robust conclusions regarding the similarities or differences in the environmental factors that shape the composition of these communities in soil.

The Hoosfield acid strip, at Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, UK, is a long-term field experiment ideal for examining the effects of pH on soil microbial communities (see Materials and methods). There are minimal differences in microbial CO2 production rates across this pH gradient, with basal respiration decreasing by only 30% from pH 8.3 to 4.5. Fungal and bacterial biomass (estimated using PLFA and ergosterol; Rousk et al., 2009) and total microbial biomass C and N (measured using a variety of methods; Aciego Pietri and Brookes, 2007b, 2009; Rousk et al., 2009, 2010a) also remained very stable across the gradient. However, bacterial and fungal growth, estimated by leucine incorporation and acetate incorporation into ergosterol, respectively, revealed dramatic differences in the activity of these microbial decomposer communities (Rousk et al., 2009). Bacterial growth was highest at the highest pH values of the gradient and declined by a factor of 5 toward the lower pH values. In contrast, fungal growth was maximal at pH 4.5, and decreased by a factor of more than 5 toward the high pH end. Across the same gradient, PLFA-based analyses suggested that the composition of the microbial community was highly influenced by the changing soil pH across this gradient (Aciego-Pietri and Brookes, 2009; Rousk et al., 2010a). However, the limited taxonomic resolution of this technique did not allow us to identify the specific microbial groups that shift in abundance across the pH gradient nor could we specifically identify changes in bacterial versus fungal community composition and diversity. The application of bar-coded pyrosequencing (Fierer et al., 2008; Hamady et al., 2008) allows for more detailed phylogenetic and taxonomic surveys of microbial communities than provided with other techniques, including PLFA and DNA fingerprinting, while also making it possible to survey a relatively large number of individual samples simultaneously.

Our objectives for this study were (i) to determine the abundance, taxonomic diversity and composition of the bacterial community across the 180-m distance of the Hoosfield acid strip (in which soil characteristics other than pH have largely been held constant), (ii) to directly compare variability in bacterial communities across this 180-m gradient with the variability across soils collected from a wide range of biomes in North and South America covering a similar pH range, and (iii) to test whether bacterial communities were more affected by soil pH than the fungal communities, as suggested by (Fierer et al., 2009; Lauber et al., 2009). To do this, we collected soils from across the Hoosfield acid strip to investigate the direct influence of soil pH on the abundance, taxonomic diversity and composition of the two major soil microbial taxa, fungi and bacteria. We used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine the relative abundance of bacteria and fungi across this gradient and a bar-coded pyrosequencing technique to analyze the composition and diversity of the bacterial and fungal communities. Finally, we directly compared the community patterns across the two very distinct sets of samples by combining the obtained data set for the bacterial community composition with that of a cross-continental study (Lauber et al., 2009).

Materials and methods

Sample collection, DNA-extraction and soil characterization

The Hoosfield acid strip is a pH gradient ranging from 4.0 to 8.3 within 200 m that resulted from a one-time uneven application of chalk in the mid 19th century. Since the chalk application, no fertilizers have been added to the soil, and winter wheat has been continuously grown. Other environmental factors vary minimally along the gradient. For instance, the organic carbon (C) content of the soil is nearly constant at 0.9±0.01% and the C:N ratio is stable at about 9 between pH 4.5 and 8.3 (Rousk et al., 2009). The soil from the Hoosfield Acid strip at Rothamsted Research, UK is classified as Typic Paleudalf (USDA, United States Department of Agriculture Soil Survey Staff, 1992). Such soils are moderately well drained and developed in a relatively silty (loess containing) superficial deposit overlaying, and mixed with clay-with-flints. The plough layer is a flinty, silty clay loam, with 18–27% clay. For a full description, see Aciego-Pietri and Brookes, (2007a, 2007b).

In April 2008, we sampled along the first 180 m of the strip taking 5 cm diameter, 0–23 cm depth cores at each sampling position along the gradient. The gradient was sampled every 10 m between 0–40 m, then every 5 m between 40 and 120 m and, then every 10 m between the final 120–180 m of the gradient (Rousk et al., 2009). The greater sampling intensity between 40–120 m was based on the faster pH changes observed previously within that interval (Aciego Pietri and Brookes, 2007a). Twenty-seven soil samples were sieved (<2.8 mm) in the laboratory, removing apparent roots and stones, and water contents determined (105 °C; 24 h). The soil samples were stored frozen until molecular analyses were performed in January 2009. The DNA was extracted from 0.5 g subsamples using the MoBio PowerSoil DNA extraction kit (Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantitative PCR analyses

Relative abundances of bacterial and fungal small-subunit rRNA gene copies were quantified using the method described by Fierer et al. (2005). For fungi, the forward primer used was 5.8 s combined with the reverse primer, ITS1f, while the forward primer Eub338 and reverse primer Eub518 was used for bacteria (Fierer et al., 2005). To estimate bacterial and fungal small-subunit rRNA gene abundances, standard curves were generated using a 10-fold serial dilution of a plasmid containing a full-length copy of either the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene or the Saccharomyces cerevisiae 18S rRNA gene. The 25 μg qPCR reactions contained 12.5 μl ABgene SYBR MasterMix (ABgene, Rochester, NY, USA), 0.5 μl of each 10-μM forward and reverse primers, and 9.5 μl sterile, DNA-free water. Standard and environmental DNA samples were added at 2.0 μl per reaction. The reaction was carried out on an Eppendorf Master-cycler ep Realplex thermocycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) using a program of 94 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s. Melting curve and gel electrophoresis analyses were performed to confirm that the amplified products were of the appropriate size. Fungal and bacterial gene copy numbers were generated using a regression equation for each assay relating the cycle threshold (Ct) value to the known number of copies in the standards. All qPCR reactions were run in quadruplicate with the DNA extracted from each soil sample.

Bar-coded pyrosequencing of fungal and bacterial communities

Amplification, purification, pooling and pyrosequencing of a region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were performed as described by Fierer et al. (2008). The fungal community was analyzed using an identical approach, except that we substituted a primer set adapted for pyrosequencing as described by Borneman and Hartin (2000). The forward primer consists of the 454 adapter B, a 2-bp linker sequence (AG) and the 817f 18S rRNA-specific primer (5′-TTAGCATGGAATAATRRAATAGGA-3′). The reverse primer consists of the 454 adapter A, a 12-bp barcode, a 2-bp linker sequence (AC) and the 1196r primer (5′-TCTGGACCTGGTGAGTTTCC-3′). This primer set was selected because it has been shown to be fungal-specific and targets a region of the 18S rRNA gene, which is variable between major taxa and can be aligned (permitting phylogenetic analyses such as UniFrac). However, it should be noted that this gene region is not sufficiently variable to permit detailed taxonomic identification of fungal communities and thus community analyses are restricted to the family level or above.

Processing of pyrosequencing data

Community level diversity across the pH gradient was analyzed by comparing the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with an OTU defined at the 97% similarity level for both bacteria and fungi (Kunin et al., 2010). To correct for survey effort (number of sequences analyzed per sample), we used a randomly selected subset of sequences per soil sample to compare relative differences in OTU-level diversity across the gradient. Of the 27 soil samples that were collected, we only included those samples for which we obtained at least 600 bacterial sequences per sample or at least 85 fungal sequences per sample for subsequent community analyses (22 and 16 samples from the bacterial and fungal analyses, respectively; there were no apparent biases with distribution of the omitted samples and high and low pH). These levels of per-sample sequencing effort are not sufficient to characterize the full extent of bacterial and fungal diversity in the collected soils. However, previous study suggests that we can quantitatively compare overall community composition and relative differences in diversity with these levels of sequencing effort (Shaw et al., 2008).

Data were processed as described by Fierer et al. (2008) using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) toolkit (Caporaso et al., 2010). In brief, bacterial and fungal sequences were quality trimmed, and assigned to soil samples based on their barcodes. Bacterial sequences were binned into OTUs using a 97% identity threshold with cd-hit (Li and Godzik, 2006), and the most abundant sequence from each OTU was selected as a representative sequence for that OTU. Taxonomy was assigned to bacterial OTUs by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) for each representative sequence against a subset of the Silva database (the full database filtered at 97% sequence identity using cd-hit). Phylogenetic trees were then built from all representative sequences using the FastTree algorithm (Price et al., 2009). The differences in overall community composition between each pair of samples was determined using the unweighted UniFrac metric (Lozupone and Knight, 2005; Lozupone et al., 2006), which calculates the distance between any pair of communities based on the fraction of unique (nonoverlapping) branch length of their sequences in the tree (Lozupone and Knight, 2005).

Taxonomic classification of the fungal pyrosequencing reads and annotation of a reference phylogenetic tree for the UniFrac analysis was carried out by BLASTing to the fungal component of the Silva database (Pruesse et al., 2007). Specifically, the fungal pyrosequencing reads were BLASTed against a database of the 18S rRNA sequences from Silva, and the sequences were assigned to their closest BLAST hit. A total of 118 of the sequences had no hit below a P<10–30 threshold and were excluded from the UniFrac and taxonomic analysis. These likely represent fungal sequences that are highly divergent from those for which near full-length sequences have been previously recovered. The remaining sequences mapped to a total of 725 reference sequences in the Silva database. The % identity similarity to the assigned sequence ranged from 84.4–100% with an average value of 98.3%. UniFrac analysis was performed using the Fast UniFrac Web interface, the Silva reference tree and an environment file mapping pyrosequencing reads to Silva reference sequences for each sample as described previously (Hamady et al., 2010). All UniFrac analyses were performed on a set surveying effort, at 600 randomly selected sequences per sample for bacteria and 85 for fungi, thus including 22 samples for the bacterial analysis and 16 for the fungal analysis.

To compare the variability in bacterial community composition across this pH gradient to variability across soils collected from a wide range of biomes from North and South America, we combined the data set from this study and that previously reported by Lauber et al. (2009), calculating pairwise unweighted UniFrac distances between each of the 110 soils. The UniFrac analyses were performed at a set surveying effort of 600 randomly selected sequences per sample. Although identical molecular methods were used to analyze both sets of samples, the soils were not collected in an identical manner. For example, the soils from this study were collected from the top 23 cm of mineral soil, whereas those from Lauber et al. (2009), see also (Fierer and Jackson, 2006), were collected from the top 5 cm of mineral soil. Nevertheless, we conducted this direct comparison to qualitatively compare patterns in bacterial community composition across a range of spatial scales.

Statistical analyses

Rarefaction curves generated using Primer v6 were used to compare relative levels of fungal and bacterial OTU diversity across the gradient. The relationships between the copy number of bacteria and fungi with soil pH, and between the taxonomic diversity for the two groups with pH, were tested with linear regression analyses. Pairwise UniFrac distances calculated for the bacterial and fungal communities were visualized using nonmetric multidimensional scaling plots (Primer v6). Principal coordinate analyses (Multi-Variate Statistical Package for Windows) were used to determine the relationship between pH and UniFrac distances by regressing scores for the first principal coordinate against pH. Inspection of the residuals of a linear curve fitted to the bacterial PCo1 and soil pH revealed this not to be randomly distributed round the line, whereas a second degree polynomial function gave a better fit. In addition, we used Mantel tests to test for statistical significance between the UniFrac composition of the fungal and bacterial communities and soil pH (Primer v6). Linear regressions were used to test the relationships between the relative abundances of bacterial and fungal taxa with pH. To avoid the potential substrate effects below pH 4.5, due to the confounding factor of impeded plant growth below this pH (see Discussion section), regressions were performed for data points between pH 4.5 and 8.3 only.

Results

qPCR estimates of bacterial and fungal abundance

The abundance of bacteria, as determined using qPCR, increased nearly fourfold across the pH gradient from low to high pH (Figure 1a, P=0. 002; r2=0.33). The abundance of fungi did not show a consistent relationship with pH across the gradient (Figure 1b). This resulted in no significant relationship between pH and fungal-to-bacterial small-subunit rRNA gene copy ratios across the gradient (P=0.40, r2=0.03).

Taxonomic diversity

For the bacterial community analyses in the 22 soil samples used from across the gradient, we obtained a total of 32 900 (89% of the total 37 000) that could be classified for a mean of 1500 classifiable sequences per sample used in the subsequent analyses (range 600–2000). The number of OTUs per bacterial community determined at the same level of surveying effort (600 sequences per sample) was positively related to soil pH (P<0.0001; r2=0.75), effectively doubling between pH 4.0 and pH 8.3 (Figure 2a).

The number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of bacteria (a) and fungi (b) across the Hoosfield acid strip. The bacterial community was sampled at the 600 sequences level, and the fungal community was sampled at the 85 sequences level. Linear functions were used to describe the OTU richness to pH relationships.

For the fungal community analyses, we obtained a total of 4700 classifiable sequences among the 16 samples used for an average of 290 fungal sequences per soil sample. The number of fungal OTUs per sample, determined at the same level of surveying effort (85 sequences per sample), showed a weak and nonsignificant relationship to soil pH (P=0.08, r2=0.21), with OTU numbers increasing marginally as soil pH increased (Figure 2b).

Bacterial community composition

There was a strong influence of soil pH on the composition of the bacterial communities across the gradient. This is evident from the nonmetric multidimensional scaling plot ordination of the pairwise UniFrac distances that illustrate how bacterial communities of different pH align along the first dimension of the plot (Figure 3a). Mantel tests corroborated this finding, indicating a strong relationship between the bacterial community composition and soil pH (Spearman r=0.96; P<0.001), as did a regression between the scores on the first principal coordinate axis (PCo1) and soil pH (Figure 3c; P<0.0001; r2=0.994). Including organic C, total N or the C:N ratio of the soil samples did not significantly improve the model over soil pH alone. Although changes in the relative sequence abundance of acidobacterial groups were pronounced (see below), excluding all acidobacteria from the UniFrac analysis of the bacterial community did not diminish the correlation with soil pH (Mantel test: Spearman r=0.94, P<0.001). The second-degree polynomial function used to describe the relationship between PCo1 and pH indicated that the dissimilarity in the bacterial community composition (PCo1 difference) was smaller at the higher pH end than at the lower end, and that incremental differences in bacterial community composition with pH were insignificant above pH 6.8. This was also corroborated by a direct comparison of the UniFrac dissimilarity values. The dissimilarity between the bacterial community in soils at pH 6.82±0.16 (n=3; average±s.e.) was on average not appreciably different from the bacterial community in soils of pH 8.02±0.06 (n=6); The UniFrac dissimilarity within pH 8.02 was 0.72±0.005, whereas UniFrac dissimilarity between pH 6.82 and 8.02 was 0.73±0.02.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots derived from pairwise unweighted UniFrac distances between soil samples with symbols coded by pH category (a and b), and the first component from a principal coordinate analysis (which explained 29.1% of the bacterial community composition variation and 17.3% of the fungal community composition variation, respectively) of the pairwise unweighted UniFrac distances regressed against soil pH using a second-degree polynomial function for the bacterial community (c) and a linear function for the fungal community (d).

The phylogenetic distances between soil bacterial communities across the pH gradient (Figure 3) were clearly related to shifts in the relative abundances of bacterial taxa at the phylum and subphylum levels (Figure 4). The relative abundances of Acidobacteria subgroups 1, 2 and 3 decreased with increasing soil pH. The relative abundance of Acidobacteria subgroups 5, 6 and 7 increased with soil pH (Figures 4a–h). Except for high values at the extreme low end of the pH scale (<pH 4.1), the relative abundance of Actinobacteria was largely unaffected by soil pH (Figure 4i). Similarly, the relative abundance of Bacteriodetes (Figure 4j) did not show clear relationships with soil pH. Nitrospira was relatively more abundant at higher soil pH but the trend was not significant (Figure 4k). Above pH 4.5, the α-, β-, γ- and δ-Proteobacteria all increased in relative abundance with increasing soil pH, but these trends were only significant for the γ-Proteobacteria. The single largest bacterial group in the low pH soils was Acidobacteria subgroup 1 (at almost 40% of the sequences), whereas α-Proteobacteria were most abundant in the high pH soils in which this group represented about 40% of all sequences.

The relationships between relative abundances of 15 dominant bacterial groups and soil pH. Linear regressions were used to test the relationship between the taxa's relative abundances and pH. To avoid the possible confounding substrate influence below pH 4.5, due to impeded plant growth below this pH (see Discussion section), only data points between pH 4.5 and 8.3 (filled circles) were used for the analyses, and data points below pH 4.5 (open circles) were excluded. Panels (a)–(o) depict the relationships between specific bacterial taxa as defined in each panel.

Fungal community composition

As with the bacterial communities, the composition of the fungal communities was also related to soil pH, although the relationship was far weaker (Figure 3b). Mantel tests corroborated this pattern, indicating a significant, albeit weaker relationship between fungal community composition and soil pH than was observed with the bacterial community (Spearman r=0.37; P<0.001), a pattern corroborated by a regression between the scores on PCo1 and soil pH (P=0.001; r2=0.55, Figure 3d). Including organic C, total N or the C:N ratio of the soil samples did not significantly improve the model over soil pH alone.

The phylogenetic distances between soil fungal communities across the pH gradient (Figure 3) were not clearly related to shifts in the relative abundances of major fungal groups (ascomycete, basidiomycete or chytridiomycete) as these fungal groups made up approximately 45, 30 and 25% of the sequences in each sample, respectively, regardless of soil pH. However, if we examine the fungal communities in more detailed levels of taxonomic resolution, some patterns with pH were evident (Figure 5). For instance, the relative abundance of a sequence with an average of 99.6% sequence similarity to the ascomycete group Hypocreales (Silva accession number AY526489) increased from being absent below pH 5.5 to making up nearly 5% of the sequences at the high pH end (Figure 5b). Conversely, a sequence with an average of 99.8% sequence similarity to the ascomycete group Helotiales (Silva accession number DQ471005) and one with 99.0% sequence similarity to the mitosporic basidiomycete group (Silva accession number AJ319755) both decreased from making up nearly 6 and 30% of the sequences at the low pH end, respectively, to very low relative abundances at the high pH end (Figures 5a and c).

The relationships between relative abundances of three abundant fungal sequences and soil pH. The fungal sequences include one with an average sequence similarity of 99.8% to accession number DQ471005 of the Silva database, a Helotiales (a), one with an average similarity of 99.6% to accession number AY526489, a Hypocreales (b), and one with an average similarity of 99.0% to accession number AJ319755, a mitosporic basidiomycete (c). Linear regressions were used to test the relationship between relative abundances and pH. To avoid the possible confounding substrate influence below pH 4.5, due to impeded plant growth below this pH (see Discussion section), only data points between pH 4.5 and 8.3 (filled circles) were used for the analyses, and data points below pH 4.5 (open circles) were excluded.

Comparison with a cross-continental pH gradient

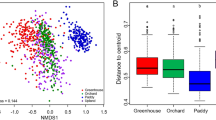

To compare the variability in bacterial community composition across this pH gradient with the variability observed in communities collected from across North and South America, representing a wide range of biomes and soils with pH values ranging from below 3.5 to nearly 9.0, we directly compared the bacterial communities in the soils studied here with those described by Lauber et al. (2009). The variation in bacterial community composition across the single soil type examined here was shown to be of nearly identical magnitude to the cross-biome variation in bacterial communities reported by Lauber et al. (2009) (Figure 6). In other words, there was as much variability in the soil bacterial communities across the Hoosfield acid strip (that is, across a distance of only 180 m) as across a wide range of biomes separated by many thousands of kilometers with a qualitatively similar influence of pH on bacterial community composition evident across both sets of samples.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots derived from pairwise unweighted UniFrac distances between soil samples of the Hoosfield soils (filled circles) and the 88-soil cross-biome study by Lauber et al. (2009) (filled diamonds) with symbols color-coded by pH category.

Discussion

Soil pH has a strong influence on the diversity and composition of soil bacterial communities across the entire gradient. This corroborates the positive relationship between bacterial diversity and higher soil pH (in the interval pH 4–7) observed in, for example, Lauber et al. (2009), confirming that this pattern is robust across different spatial scales and soil types. This is not the first study to show that soil pH has a strong influence on bacterial community composition. Similar results have been reported using other techniques with more limited resolution than pyrosequencing. For instance, the microbial PLFA composition, which primarily reflects the structure of the bacterial community (as few markers are associated with fungi), has been shown to be highly influenced by soil pH (Nilsson et al., 2007; Bååth and Anderson, 2003). Recently, this has also been reported in the pH gradient studied here (Aciego Pietri and Brookes, 2009; Rousk et al., 2010a). In addition, characterizations of soil bacterial communities across a wide range of sample sets have consistently indicated the same powerful correlation between soil pH and bacterial community composition, regardless of the technique used, including DNA fingerprinting-based techniques (Fierer and Jackson, 2006; Männistö et al., 2007; Jenkins et al., 2009), clone library-based techniques (Lauber et al., 2008; Jesus et al., 2009) and pyrosequencing-based techniques (Lauber et al., 2009).

The results from previous studies are thus corroborated by our results, and the strong connection between pH and the bacterial community composition is consequently consistent both across biomes, in which many soil and site characteristics other than pH also change (the listed studies above), and across an experimental pH gradient established on a single soil type in which the other soil characteristics (for example, vegetation type, texture, moisture and carbon concentrations) vary minimally (this study). We also directly related the data set from an inter-biome collection of very different soils (Lauber et al., 2009) to the relationship between bacterial community composition and soil pH in the this study (Figure 6). This comparison emphasized the canonical influence of soil pH on the bacterial community: bacterial communities separated by less than 180 m were often as different as bacterial communities in soils collected from very different biomes across North and South America. This implies that pH is greater driver of bacterial community composition than dispersal limitation and other environmental factors that vary between biomes.

These results raise the question: why is soil pH so often such a good predictor of bacterial community composition, both across biomes and within an individual soil type? One hypothesis is that the communities are directly influenced by soil pH due to most bacterial taxa exhibiting relatively narrow growth tolerances. This is in close accordance with the usually narrow pH range permissive for growth of individual bacterial species in pure culture, usually varying between 3–4 pH units between minimum and maximum (Rosso et al., 1995). In addition, pH optima for natural bacterial communities of different soils are closely constrained to their in situ pH (Bååth, 1996). Deviations of 1.5 pH units from in situ pH of bacterial communities consistently reduce their activity by 50% (Fernández-Calviño and Bååth, 2010). A growth decrease of only 25% compared with optimum growth would lead to a population being rapidly outcompeted by other bacteria that were not impeded. These narrow pH optima for bacterial strains would explain the strong relationship between bacterial community composition and soil pH.

The shifts in the relative abundances of specific taxonomic groups across this pH gradient are similar to the pH responses observed in other studies. For instance, the relative abundance of Acidobacteria has been shown to increase toward lower pH (Männistö et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2009; Dimitriu and Grayston, 2010). In addition, subgroups within the Acidobacteria phylum have also been shown to be strongly, and differentially, affected by pH. For instance, Acidobacteria subgroups 1 and 2, the most abundant groups, have previously been found to be negatively dependent on pH (Jones et al., 2009), a result that is corroborated in the results of this study. However, Acidobacteria subgroup 3 demonstrated a similar positive trend with lower pH in this study, which has not been discerned previously. Conversely, Acidobacteria subgroup 4, but also subgroups 6, 7 and 16, have been found to positively correlate with higher pH (Jones et al., 2009), which is partially corroborated by our results. The strong positive correlation between the relative abundance of both Actinobacteria and Bacteriodetes with higher pH previously reported for a wide range of soils from different biomes (Lauber et al., 2009) was, however, not seen in the Hoosfield acid strip. This may indicate that the previously observed connection between these phyla and soil pH may in fact have been related to another soil or site characteristic (for example, C availability or soil moisture) that may have co-varied with soil pH.

The relative abundances of proteobacterial groups tended to be positively related to pH across the Hoosfield acid strip, a pattern that was not evident in the cross-continental study in which many soil types were included (Lauber et al., 2009). High abundances of proteobacterial groups have previously been connected with higher availability of C (McCaig et al., 1999; Axelrood et al., 2002; Kirchman, 2002; Fazi et al., 2005: Fierer et al., 2007). Plant growth (sown wheat) along the Hoosfield acid strip has been noted to decrease sharply below pH 4.5 (JC Aciego-Pietri, unpublished data), resulting in correspondingly reduced plant-C input available to the microorganisms. This decrease in the availability of C at low pH might have contributed to the change in relative abundance of Proteobacteria with increasing pH. Low plant growth at low pH may also explain the different trend for abundance of some bacterial groups below pH 4.5, including, for example, Actinobacteria (Figure 4i) and Acidobacteria subgroup 2 (Figure 4b).

This study is the one of the few pyrosequencing-based assessments of the fungal community in soils, and it is one of only a few studies to combine sequence-based assessments of both the bacterial and fungal communities together. A consequence of this is that the influence of soil pH on the fungal community has been less explored than effects of soil pH on the bacterial community. We found that the composition of the fungal community was related to soil pH, but the influence was far weaker than for the bacterial community. This may be related, in part, to the ability of the applied method to document the phylogenetic differences between the fungal communities across this gradient. However, these results do agree with physiological studies of bacterial and fungal pure cultures, indicating that these microbial groups differ in their responses to pH. Fungal species typically have a wide pH optimum, often covering 5–9 pH units without significant inhibition of their growth (Wheeler et al., 1991; Nevarez et al., 2009). The available evidence for the fungal pH relationship thus indicates a significantly weaker direct connection with pH than bacteria (Beales, 2004), although pure culture studies have shown preference for certain pH values for different taxa of soil fungi (Domsch et al., 1980). For instance, the fungal genus Mariannaea, with 100% sequence similarity to an abundant sequence of the ascomycete Hypocreales group (Figure 5b), has been determined to grow between pH 5.5 and 8.5 in culture-based studies (Domsch et al., 1980), which matches the results obtained in the present study. Alternatively, it is possible that competitive interactions between fungi and bacteria could, in part, be driving the observed fungal community shifts across a steep gradient of bacterial community change. For instance, removal experiments revealed intensive fungal–bacterial interaction in soil in which inhibition of the bacterial community immediately stimulated fungi (Rousk et al., 2008). Furthermore, when similar experiments were recently used to inhibit bacterial growth along the pH gradient in Hoosfield, there were indications of high fungal growth at all pHs (Rousk et al., 2010b). This could suggest that the observed pattern between the fungal community composition and soil pH is an indirect effect, mediated by the competitive influence from the highly dynamic bacterial community along the pH gradient.

The soil pH effect on the abundance (qPCR copy number) of both bacteria and fungi was relatively modest. There was a small positive relationship between the abundance of bacteria and higher pH, increasing nearly twofold, whereas fungal abundance was unaffected. It should be noted that qPCR does not provide an estimate of biomass ratios because ribosomal gene copy number and cellular nucleic acid concentrations can vary between taxa. However, it has been shown to provide a reproducible metric to track shifts in the relative abundances of bacteria and fungi across a landscape (Fierer et al., 2005). Corroborating this finding, our results indicate that the qPCR results are largely in line with alternative biomass measurements previously made on the same gradient (for example, Rousk et al., 2009, 2010a). Thus qPCR, supported by the previously applied biomass methods, may provide reasonable indices of standing biomass pool sizes, but such methods do not resolve the dynamics in the active fungal and bacterial communities that were demonstrated previously using growth-based measurements (Rousk et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the composition of the bacterial community in the Hoosfield acid strip was sharply defined by soil pH. This corroborates the results from the inter-biome pH gradient studied by Lauber et al. (2009), and many others, which included a wide range of soil types, and suggests that pH is more important overall for structuring soil communities than is biome type. When the results from the studies were combined, there was as much variability in bacterial community composition across the 180 m distance of this liming experiment as across soils collected from a wide range of biomes in North and South America. The apparent stronger influence by pH on the bacterial community composition is probably due to the narrow pH ranges for optimal growth of bacteria, whereas the weaker influence by pH on the fungal community composition is consistent with pure culture studies, demonstrating that fungi generally exhibit wider pH ranges for optimal growth.

References

Aciego Pietri JC, Brookes PC . (2007a). Nitrogen mineralisation along a pH gradient of a silty loam UK soil. Soil Biol Biochem 40: 797–802.

Aciego Pietri JC, Brookes PC . (2007b). Relationships between soil pH and microbial properties in a UK arable soil. Soil Biol Biochem 40: 1856–1861.

Aciego Pietri JC, Brookes PC . (2009). Substrate inputs and pH as factors controlling microbial biomass, activity and community structure in an arable soil. Soil Biol Biochem 41: 1396–1405.

Axelrood PE, Chow ML, Radomski CC, McDermott JM, Davies J . (2002). Molecular characterization of bacterial diversity from British Columbia forest soils subjected to disturbance. Can J Microbiol 48: 655–674.

Bååth E . (1996). Adaptation of soil bacterial communities to prevailing pH in different soils. FEMS Microb Ecol 19: 227–237.

Bååth E, Anderson TH . (2003). Comparison of soil fungal/bacterial ratios in a pH gradient using physiological and PLFA-based techniques. Soil Biol Biochem 35: 955–963.

Baker KL, Langenheder S, Nicol GW, Ricketts D, Killham K, Campbell CD et al. (2009). Environmental and spatial characterisation of bacterial community composition in soil to inform sampling strategies. Soil Biol Biochem 41: 2292–2298.

Beales N . (2004). Adaptation of microorganisms to cold temperature, weak acid preservatives, low pH, and osmotic stress: a review. Comp Rev Food Sci F 3: 1–20.

Bennett LT, Kasel S, Tibbits J . (2009). Woodland trees modulate soil resources and conserve fungal diversity in fragmented landscapes. Soil Biol Biochem 41: 2162–2169.

Borneman J, Hartin REJ . (2000). PCR primers that amplify fungal rRNA genes from environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 4356–4360.

Buée M, Reich M, Murat C, Morin E, Nilsson RH, Uroz S et al. (2009). 454 pyrosequencing analyses of forest soils reveal an unexpectedly high fungal diversity. New Phytol 184: 449–456.

Caporaso JS, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. (2010). QIIME allows integration and analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods (in press), doi:10.1038/nmeth.f.303.

Davis JP, Youssef NH, Elshahed MS . (2009). Assessment of the diversity, abundance, and ecological distribution of candidate division SR1 reveals a high level of phylogenetic diversity but limited morphotypic diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 4139–4148.

Dimitriu PA, Grayston SJ . (2010). Relationship between soil properties and patterns of bacterial β-diversity across reclaimed and natural boreal forest soils. Microb Ecol 59: 563–573.

Domsch KH, Gams W, Anderson TH . (1980). Compendium of Soil Fungi Volume 1 Academic Press: London.

Fazi S, Amalfitano S, Pernthaler J, Puddu A . (2005). Bacterial communities associated with benthic organic matter in headwater stream microhabitats. Environ Microbiol 7: 1633–1640.

Fernández-Calviño D, Bååth E . (2010). Growth response of the bacterial community to pH in soils differing in pH. FEMS Microbiol Ecol (in press), doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00873.x.

Fierer N, Bradford MA, Jackson RB . (2007). Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 88: 1354–1364.

Fierer N, Hamady M, Lauber CL, Jackson RB . (2008). The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17994–17999.

Fierer N, Jackson RB . (2006). The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 626–631.

Fierer N, Jackson JA, Vilgalys R, Jackson RB . (2005). Assessment of soil microbial community structure by use of taxon-specific quantitative PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 4117–4120.

Fierer N, Strickland MS, Lipzin D, Bradford MA, Cleveland CC . (2009). Global patterns in belowground communities. Ecol Lett 12: 1238–1249.

Frey SD, Knorr M, Parrent JL, Simpson RT . (2004). Chronic nitrogen enrichment affects the structure and function of the soil microbial community in temperate hardwood and pine forests. For Ecol Manag 196: 159–171.

Hamady M, Lozupone C, Knight R . (2010). Fast UniFrac: facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and PhyloChip data. ISME J 4: 17–27.

Hamady M, Walker JJ, Harris JK, Gold NJ, Knight R . (2008). Error-correcting barcoded primers for pyrosequencing hundreds of samples in multiplex. Nat Methods 5: 235–237.

Hartman WH, Richardson CJ, Vilgalys R, Bruland GL . (2008). Environmental and anthropogenic control of bacterial communities in wetland soils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17842–17847.

Jenkins SN, Waite IS, Blackburn A, Husband R, Rushton SP, Manning DC et al. (2009). Actinobacterial community dynamics in long term managed grasslands. 95: 319–334.

Jesus ED, Marsh TL, Tiedje JM, Moreira FMD . (2009). Changes in lands use alter the structure of bacterial communities in Western Amazon soils. ISME J 3: 1004–1011.

Jones RT, Robeson MS, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N . (2009). A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J 3: 442–453.

Kirchman DL . (2002). The ecology of Cytophaga–Flavobacteria in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 39: 91–100.

Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P . (2010). Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ Microbiol 12: 118–123.

Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N . (2009). Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community composition at the continental scale. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 5111–5120.

Lauber CL, Strickland MS, Bradford MA, Fierer N . (2008). The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land-use types. Soil Biol Biochem 40: 2407–2415.

Li W, Godzik A . (2006). Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22: 1658–1659.

Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R . (2006). UniFrac—an online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 731.

Lozupone C, Knight R . (2005). UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 8228–8235.

Männistö MK, Tiirola M, Häggblom MM . (2007). Bacterial communities in Arctic fjelds of Finnish Lapland are stable but highly pH dependent. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 59: 452–465.

McCaig AE, Glover LA, Prosser JI . (1999). Molecular analysis of bacterial community structure and diversity in unimproved and improved upland grass pastures. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 1721–1730.

Nevarez L, Vasseur V, Le Madec L, Le Bras L, Coroller L, Leguérinel I et al. (2009). Physiological traits of Penicillium glabrum strain LCP 08.5568, a filamentous fungus isolated from bottled aromatised mineral water. Int J Food Microbiol 130: 166–171.

Nicol GW, Leininger S, Schleper C, Prosser JI . (2008). The influence of soil pH on the diversity, abundance and transcriptional activity of ammonia oxidizing archaea and bacteria. Environ Microbiol 10: 2966–2978.

Nilsson LO, Bååth E, Falkengren-Grerup U, Wallander H . (2007). Growth of ectomycorrhizal mycelia and composition of soil microbial communities in oak forest soils along a nitrogen deposition gradient. Oecologia 153: 375–384.

Philippot L, Cuhel J, Saby NPA, Chèneby D, Chronáková A, Bru D et al. (2009). Mapping fine-scale spatial patterns of size and activity of the denitrifier community. Environ Microbiol 11: 1518–1526.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP . (2009). Fasttree: computing large minimum-evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26: 1641–1650.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs B, Ludwig W, Peplies J et al. (2007). SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7188–7196.

Rosso L, Lobry JR, Bajard S, Flandrois JP . (1995). Convenient model to describe the combined effects of temperature and pH on microbial growth. Appl Environ Microbiol 61: 610–616.

Rousk J, Aldén Demoling L, Bahr A, Bååth E . (2008). Examining the fungal and bacterial niche overlap using selective inhibitors in soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 63: 350–358.

Rousk J, Brookes PC, Bååth E . (2009). Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggests functional redundancy in carbon mineralisation. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 1589–1596.

Rousk J, Brookes PC, Bååth E . (2010a). The microbial PLFA composition as affected by pH in an arable soil. Soil Biol Biochem 42: 516–520.

Rousk J, Brookes PC, Bååth E . (2010b). Investigating the mechanisms for the opposing pH-relationships of fungal and bacterial growth in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 42: 926–934.

Shaw AK, Halpern AL, Beeson K, Tran B, Venter JC, Martiny JBH . (2008). It's all relative: ranking the diversity of aquatic bacterial communities. Environ Microbiol 10: 2200–2210.

USDA (United States Department of Agriculture Soil Survey Staff (1992). Keys to soil taxonomy. SMSS Technical Monograph 19. Pocahontas Press: Blacksburg, VA, 541.

Wheeler KA, Hurdman BF, Pitt JI . (1991). Influence of pH on the growth of some toxigenic species of Aspergillus, Penicillium and Fusarium. Int J Food Microbiol 12: 141–150.

Acknowledgements

We thank D Ahrén for helpful discussions and M Hamady for assistance with bioinformatics. This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR) and from the Royal Physiographic Society of Lund (Kgl Fysiografen) (to JR). This study was also supported by grants from the US National Science Foundation, the US Department of Agriculture and the AW Mellon Foundation to NF and by a grant from the Swedish Research Council (VR) to EB

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rousk, J., Bååth, E., Brookes, P. et al. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J 4, 1340–1351 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.58

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.58

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of simulated atmospheric nitrogen deposition on the bacterial community structure and diversity of four distinct biocolonization types on stone monuments: a case study of the Leshan Giant Buddha, a world heritage site

Heritage Science (2024)

-

Land management shapes drought responses of dominant soil microbial taxa across grasslands

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Pervasive associations between dark septate endophytic fungi with tree root and soil microbiomes across Europe

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Identifying key soil characteristics for Francisella tularensis classification with optimized Machine learning models

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Soil microbial communities alter resource allocation in Fagus grandifolia when challenged with a pathogen

Symbiosis (2024)