Abstract

Microorganisms capable of actively solubilizing and precipitating gold appear to play a larger role in the biogeochemical cycling of gold than previously believed. Recent research suggests that bacteria and archaea are involved in every step of the biogeochemical cycle of gold, from the formation of primary mineralization in hydrothermal and deep subsurface systems to its solubilization, dispersion and re-concentration as secondary gold under surface conditions. Enzymatically catalysed precipitation of gold has been observed in thermophilic and hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea (for example, Thermotoga maritime, Pyrobaculum islandicum), and their activity led to the formation of gold- and silver-bearing sinters in New Zealand's hot spring systems. Sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB), for example, Desulfovibrio sp., may be involved in the formation of gold-bearing sulphide minerals in deep subsurface environments; over geological timescales this may contribute to the formation of economic deposits. Iron- and sulphur-oxidizing bacteria (for example, Acidothiobacillus ferrooxidans, A. thiooxidans) are known to breakdown gold-hosting sulphide minerals in zones of primary mineralization, and release associated gold in the process. These and other bacteria (for example, actinobacteria) produce thiosulphate, which is known to oxidize gold and form stable, transportable complexes. Other microbial processes, for example, excretion of amino acids and cyanide, may control gold solubilization in auriferous top- and rhizosphere soils. A number of bacteria and archaea are capable of actively catalysing the precipitation of toxic gold(I/III) complexes. Reductive precipitation of these complexes may improve survival rates of bacterial populations that are capable of (1) detoxifying the immediate cell environment by detecting, excreting and reducing gold complexes, possibly using P-type ATPase efflux pumps as well as membrane vesicles (for example, Salmonella enterica, Cupriavidus (Ralstonia) metallidurans, Plectonema boryanum); (2) gaining metabolic energy by utilizing gold-complexing ligands (for example, thiosulphate by A. ferrooxidans) or (3) using gold as metal centre in enzymes (Micrococcus luteus). C. metallidurans containing biofilms were detected on gold grains from two Australian sites, indicating that gold bioaccumulation may lead to gold biomineralization by forming secondary ‘bacterioform’ gold. Formation of secondary octahedral gold crystals from gold(III) chloride solution, was promoted by a cyanobacterium (P. boryanum) via an amorphous gold(I) sulphide intermediate. ‘Bacterioform’ gold and secondary gold crystals are common in quartz pebble conglomerates (QPC), where they are often associated with bituminous organic matter possibly derived from cyanobacteria. This may suggest that cyanobacteria have played a role in the formation of the Witwatersrand QPC, the world's largest gold deposit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microorganisms play an important role in the geochemical cycling of metals. These metal cycles are driven by microorganisms, because metals are essential for microbial nutrition (for example, Mg, Na, Fe, Co, Cu, Mo, Ni, W, V, Zn; Madigan and Martinko, 2006). A number of metal ions are oxidized or reduced in catabolic reactions to gain energy (for example, As(III/V), Fe(II/III), Mn(II/IV), V(IV/V), Se(IV/VI), U(IV/VI); Tebo and Obraztsova, 1998; Stolz and Oremland, 1999; Ehrlich, 2002; Lloyd, 2003; Tebo et al., 2005; Madigan and Martinko, 2006). Metal ions (for example, Ag+, Hg2+, Cd2+, Co2+, CrO42−, Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Zn2+) can also cause toxicity through the displacement of essential metals from their native binding sites, because they possess a greater affinity to thiol-containing groups and oxygen sites than essential metals (Poole and Gadd, 1989; Nies, 1999; Bruins et al., 2000; Lloyd, 2003; Silver and Phung, 2005). Solubilization, precipitation, fractionation and speciation of metals and metal ions are also indirectly influenced by microbial activity, for example, through their influence on environmental redox conditions and pH, formation of complexing ligands and bioaccumulation (Stone, 1997; Ehrlich, 2002; Lloyd, 2003).

These mechanisms, which are widely accepted as drivers of environmental metal cycling, are now being examined using the latest molecular microbiology techniques (for example, whole-genome sequencing and RNA-expression microarrays as well as metagenomic and proteomic approaches) to link microbial processes, populations and communities directly to element transformations in the environment (Newman and Banfield, 2002; Handelsman, 2004; Tyson et al., 2004; Ram et al., 2005; Valenzuela et al., 2006; Whitaker and Banfield, 2006). The use of metagenomic and proteomic techniques has elucidated the complex interactions in a microbial community that underpins the generation of acid mine drainage and metal mobilization at the Richmond Mine in California (Tyson et al., 2004; Ram et al., 2005). This research has also led to an understanding of the adaptation mechanisms these communities use to survive under extremely acidic and toxic metal-rich conditions (Dopson et al., 2003; Druschel et al., 2004; Tyson et al., 2004; Ram et al., 2005). In other studies biochemical pathways of microbial metal and metalloid transformations (for example, oxidation, reduction, methylation, complexation and biomineralization of Fe(II/III), Mn(II/IV), As(III/V), Se(IV/VI), V(IV/V) and U(IV/VI) have been linked to biogeochemical metal cycling in sediments, soils and other weathered materials from polar, temperate, arid and tropical regions (Barns and Nierzwicki-Bauer, 1997; Stolz and Oremland, 1999; Holden and Adams, 2003; Gadd, 2004; Islam et al., 2004; DiChristina et al., 2005; Nelson and Methé, 2005; Wilkins et al., 2006; Akob et al., 2007; Edwards et al., 2007; Fitzgerald et al., 2007). In another approach Cupriavidus (formerly known as Ralstonia, Wautersia and Alcaligenes) metallidurans was used as a model organism to study the metal resistance mechanisms in bacteria, and a complex network of genetic and proteomic responses that regulate the resistance to a number of toxic metal ions, for example, Ag+, Hg2+, Cd2+, Co2+, CrO42−, Cu2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, has been described (Mergeay et al., 1985, 2003; Nies, 1992, 1995, 1999, 2003; Nies and Silver, 1995; Nies and Brown, 1998; Grosse et al., 2004; Monchy et al., 2006).

In contrast, to the metals mentioned above, gold is extremely rare, inert, non-essential, unstable as a free ion in aqueous solution under surface conditions, and as a complex, it can be highly toxic to organisms (Boyle, 1979; Witkiewicz and Shaw, 1981; Karthikeyan and Beveridge, 2002). Research into microbial processes affecting the cycling of gold as well as the physiological and biochemical responses of microorganisms to toxic gold complexes has been limited, and as a result its biogeochemical cycling and geomicrobiology are poorly understood. However, a microbially driven biogeochemical cycle of gold has been proposed, and in a number of laboratory and field studies individual aspects of this cycle have been assessed (for example, Korobushkina et al., 1983; Savvaidis et al., 1998; Mossman et al., 1999). Laboratory studies have shown that some archaea, bacteria, fungi and yeasts are able to solubilize and precipitate gold under in vitro conditions, but these experiments give only limited insights into gold solubilization and precipitation catalysed by complex microbial communities in natural environments. In a field-based approach, the morphology of secondary gold grains that display ‘bacterioform’ structures has been used as evidence for microbial gold precipitation and biomineralization in the environment (Watterson, 1992). However, analogous gold morphologies were also produced abiotically, and are therefore not sufficient proof for the bacterial origin of ‘bacterioform’ gold (Watterson, 1994). To obtain conclusive evidence for microbially mediated environmental cycling of gold, a combination of laboratory-based experiments and field observations supported by the state-of-the-art microscopy techniques (for example, high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM)), spectroscopy ((X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS)) and molecular microbial techniques (for example, 16S rDNA PCR-DGGE, shotgun cloning and sequencing, expression of functional genes) have been conducted.

The aim of this review is to integrate these recent results with the results of the earlier studies in order to trace the path of gold and associated microbial processes and populations through the environment (Figure 1). After providing an overview of the geochemical properties and constraints of gold in hydrothermal and supergene systems, the influence of bacteria and archaea on primary deposit formation as well as solubilization, redistribution and precipitation in surface environments are reviewed. Then, the microbially mediated formation of secondary octahedral gold crystals and ‘bacterioform’ gold, which are common in quartz pebble conglomerates (QPC) deposits (for example, the largest known gold deposit, the Witwatersrand QPC) are discussed because recent results have rekindled the debate of whether or not these are products of microbial processes. Thus, this review will provide the background for future research that will aim at directly linking the activities of complex microbial communities with gold cycling using advanced genomic, proteomic and spectroscopic techniques.

The geochemical characteristics of gold

Gold is one of the ten rarest elements in the Earth's crust with an average concentration of 5 ng g−1 (solid material), and a concentration range from 0.0197 to 0.197 μg l−1 in natural waters (Goldschmidt, 1954; McHugh, 1988). However, gold is not uniformly distributed and is often highly enriched in mineralized zones, where it may form economic primary deposits (for example, skarn type-, vein type- and disseminated deposits; Boyle, 1979). The deposition of gold in primary deposits usually occurs via metal-rich hydrothermal fluids, which circulate in open spaces within rocks and deposit gold as consequence of cooling or boiling (Morteani, 1999). Native primary gold is commonly present as alloys with Ag, Cu, Al, Fe, Bi, Pb, Zn, Pd or Pt, with gold concentration ranging from 50 to 80 wt% (Boyle, 1979).

Due to its low solubility in aqueous solution, its speciation and complexation is commonly deduced from thermodynamic calculations, geochemical models, laboratory studies and field observations (Boyle, 1979, Gray, 1998). In hydrothermal fluids gold is chemically mobile as complexes with sulphide and bisulphide (for example, [Au(HS)0], [Au(HS2)−], [Au2S22−]; Renders and Seward, 1989; Benning and Seward, 1996; Gammons and Williams-Jones, 1997; Gilbert et al., 1998). Deposition from these solutions leads to the formation of gold-containing sulphide minerals (for example, pyrite and arsenopyrite), in which gold is either finely dispersed in crystal lattices or occurs as solid inclusions (Boyle, 1979; King, 2002). The chemical mobility of gold in the supergene zone is linked to the weathering of these sulphide minerals, and its subsequent oxidation and complexation (Boyle, 1979; Southam and Saunders, 2005). Under surface conditions, gold occurs in aqueous ‘solution’ as metal colloid (0), and aurous (+I) and auric (+III) complexes, because standard redox potentials of Au+ (1.68 V) and Au3+ (1.50 V) exceed that of water (1.23 V), which makes the existence of free gold ions thermodynamically unfavourable (Boyle, 1979; Vlassopoulos et al., 1990a). Based on thermodynamic calculations and natural abundances of possible ligands, aqueous gold(I/III) complexes with thiosulphate and chloride appear to be the most important complexes in waters that contain little dissolved organic matter (DOM; Boyle, 1979; Mann, 1984; Vlassopoulos et al., 1990a; Benedetti and Boulegue, 1991; Gray, 1998). Thiosulphate has been shown to readily solubilize gold, and the resulting gold(I) thiosulphate complex [Au(S2O3)23−] is stable from mildly acid to highly alkaline pH, and moderately oxidizing to reducing conditions (Mineyev, 1976; Goldhaber, 1983; Webster, 1986). Thiosulphate is produced during the (bio)oxidation of sulphide minerals, and thus is likely to dominate in groundwater surrounding gold-bearing sulphide deposits (Stoffregen, 1986). Oxidizing groundwater with high dissolved chloride contents, common in arid and semi-arid zones, may also solubilize gold, leading to the formation of gold(I/III) chloride complexes ([AuCl2−], [AuCl4−]; Krauskopf, 1951; Gray, 1998). However, unlike the gold(III) chloride complex, the gold(I)-chloride complex (AuCl2−) is not be stable at low temperature (<100 °C) under oxidizing condition (Farges et al., 1991; Pan and Wood, 1991; Gammons et al., 1997).

Gold also forms complexes with organic ligands; a characteristic of Group IB metals is their ability to strongly bind to organic matter (Boyle, 1979; Vlassopoulos et al., 1990b; Gray et al., 1998). Thus, organic gold complexes may be important in soil solutions with high concentrations of DOM. However, due to the complexity of DOM, researchers have contradicting results in solubilization/precipitation experiments. Organic acids (that is, humic and fulvic acids, amino acids and carboxylic acids) have been shown to promote the solubilization of native gold in some experiments (Freise, 1931; Baker, 1973, 1978; Boyle et al., 1975; Korobushkina et al., 1983; Varshal et al., 1984). However, in other experiments native gold was not oxidized and the formation of gold colloids and sols from gold(I/III) complexes was promoted (Fetzer, 1934, 1946; Ong and Swanson, 1969; Fisher et al., 1974; Gray et al., 1998). The interaction of gold and organic matter involves mostly electron donor elements, such as N, O or S, rather than C (Housecroft, 1993, 1997a, 1997b). Vlassopoulos et al. (1990b) showed that gold binds preferentially to organic S under reducing conditions, whereas under oxidizing conditions it binds mostly to organic N and C. Organo-gold complexes can be present in aqueous solution as gold(I) cyanide complexes (Housecroft, 1993, 1997a, 1997b). Gold(I) forms a strong complex with cyanide [Au(CN)2−] that is stable over a wide range of Eh-pH conditions (Boyle, 1979; Gray, 1998).

Sorption of gold complexes and colloids to organic matter, clays, Fe and Mn minerals as well as bioaccumulation and biomineralization may lead to the formation of secondary gold particles, which are often observed close to primary deposits (see below; Boyle, 1979; Goldhaber, 1983, Webster and Mann, 1984; Webster, 1986; Lawrance and Griffin, 1994; Gray, 1998). Secondary gold is generally much finer (up to 99 wt% of gold) compared to primary gold, and the individual gold aggregates are often larger than in potential source rocks (Wilson, 1984; Watterson, 1992; Mossman et al., 1999).

Microbial influence on the formation of primary mineralization

Bacteria and archaea are found in surface and subsurface environments up to a depth of several kilometres, and are only limited by water availability and ambient temperature (<121 °C; Inagaki et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2003; Kashefi and Lovley, 2003; Navarro-Gonzalez et al., 2003; Fredrickson and Balkwill, 2006; Teske, 2006). In ultra-deep gold mines (at depths of up to 5 km below land surface) sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB; for example, Desulfotomaculum sp.) are common (Moser et al., 2005), and may contribute to the formation of gold-containing sulphide minerals (Lengke and Southam, 2006, 2007). SRB are anaerobic, heterotrophic bacteria that use the dissimilatory sulphite reductase (Dsr) pathway for the reduction of sulphur compounds (for example, sulphate and thiosulphate) to hydrogen sulphide (H2S), which is toxic, because it inhibits the function of iron-containing cytochromes (Truong et al., 2006). Free sulphide (that is, present as H2S, HS− or S2− depending on pH) is detoxified through precipitation with metal ions, such as Fe2+, leading to the formation of metal sulphides, such as pyrite (Donald and Southam, 1999). Desulfovibrio sp. have been shown to reduce the thiosulphate from gold thiosulphate complexes; this destabilizes the gold in solution, which may then be incorporated into the newly forming sulphide minerals (Lengke and Southam, 2006). Thus, this process may contribute to the formation of economic gold deposits, if it continues over geological timescales, provided nutrients and gold(I) thiosulphate are provided to the system.

The presence of bacteria and archaea in hydrothermal systems, such as hydrothermal vents and hot springs, has been documented highlighting the growth of these organisms under extreme conditions (Barns et al., 1994; Barns and Nierzwicki-Bauer, 1997; Sievert et al., 2000; Kashefi and Lovley, 2003; Csotonyi et al., 2006). Hydrothermal vents are geological formations that release altered seawater, which has been heated to temperatures of up to 400 °C by subterranean magma pockets as it circulates through the crust, mobilizing mainly metals and sulphides (Csotonyi et al., 2006). Microbial communities present in and around these vents consist of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea, such as chemoautotrophic sulphur reducer and oxidizers, and dissimilatory metal reducers (Barns and Nierzwicki-Bauer, 1997; Kashefi and Lovley, 2003; Csotonyi et al., 2006). A study by Kashefi et al. (2001) demonstrated that hyperthermophilic dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (Thermotoga maritime) and archaea (Pyrobaculum islandicum and Pyrocococcus furiosus) are able to extracellularly precipitate gold from gold(III) chloride at 100 °C under anoxic conditions in the presence of H2 (Kashefi et al., 2001). In this system, the precipitation of gold was an active, enzymatically catalysed reaction that depended on H2 as the electron donor, and may involve a specific membrane-bound hydrogenase (Kashefi et al., 2001). Anoxic conditions and abundant H2 are common in hot springs, which occur where geothermally heated groundwater emerges from the Earth's crust. In Champagne Pool at Waitapu in New Zealand, the activity of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea led to the formation of gold- and silver-bearing sinters, with concentrations of these metals reaching more than 80 and 175 ng g−1 (material), respectively (Jones et al., 2001); additionally, biomineralization of As and Sb bearing sulphide minerals was observed (Phoenix et al., 2005). These studies suggest that microorganisms in deep subsurface and hydrothermal systems may directly contribute to the formation of primary gold mineralization.

Microbial mechanisms of gold solubilization

Microbially mediated gold solubilization depends on the ability of microorganisms to promote gold oxidation, and to excrete ligands capable of stabilizing the resulting gold ions by forming complexes or colloids. A number of microbial processes associated with different zones of the environment have been shown to fullfill these criteria. In arid, surficial environments (down to ∼500 m below the land surface; Enders et al., 2006) chemolithoautotrophic iron- and sulphur-oxidizing bacteria, such as Acidothiobacillus ferrooxidans and A. thiooxidans, and archaea, can form biofilms on metal sulphides (for example, gold-bearing pyrites and arsenopyrites), and obtain metabolic energy by oxidizing these minerals via a number of metabolic pathways, such as the sulphur oxidase pathway (Sox) and the reverse Dsr pathways (Nordstrom and Southam, 1997; Friedrich et al., 2005; Southam and Saunders, 2005). Overall, the biofilms provide reaction spaces for sulphide oxidation, sulphuric acid for a proton hydrolysis attack and keep Fe(III) in the oxidized, reactive state (Sand et al., 2001; Rawlings, 2002; Mielke et al., 2003). The high concentrations of Fe3+ and protons then attack the valence bonds of the sulphides, which are degraded via the main intermediate thiosulphate (Sand et al., 2001). The oxidation of sulphide minerals also leads to the release of associated metals into the environment (Southam and Saunders, 2005):

In this process some iron and sulphur oxidizers (for example, A. thioparus, A. ferrooxidans) excrete thiosulphate, which in the presence of oxygen leads to gold oxidation and complexation (Aylmore and Muir, 2001):

The solubilization of gold observed in a study of microcosms with quartz vein materials, containing sub-microscopic gold in arsenopyrite and pyrite from the Tomakin Park Gold Mine in temperate New South Wales, Australia, may have been mediated by this process. In biologically active systems (with live microbiota) a maximum of 550 ng gold per gram (d.w. material) was solubilized after 35 days of incubation. In contrast, sterile control microcosms displayed ten times lower concentration of solubilized gold that lay in the range of theoretical solubility for the system (McPhail et al., 2006; Reith and McPhail, 2006).

Thiosulphate is also produced by other microbial processes involving different groups of microorganisms, and may promote gold solubilization in other environmental zones. SRB common in anoxic metal-rich sulphate-containing zones, for example, acid sulphate soils, form thiosulphate during the reduction of sulphite with H2 and formate (Fitz and Cypionka, 1990). Streptomycetes fradiae, a common soil actinomycete, produces thiosulphate as a result of the metabolization of sulphur from cystine (Kunert and Stransky, 1988).

In a microcosm study with organic matter-rich auriferous (gold-containing) soils from the Tomakin Mine Park Mine in New South Wales, Australia, the biologically active microcosm displayed up to 80 wt.% gold solubilization within 20–45 days of incubation, after which it was re-adsorbed to the solid soil fractions (Figure 2; Reith and McPhail, 2006). In biologically active microcosms amended with native 99.99% pure gold pellets, gold was liberated from the pellets as well as the soil, and the formation of bacterial biofilms on the gold pellets was observed; in contrast, gold was not solubilized in sterile controls (Figure 2; Reith and McPhail, 2006). Similar results were also obtained in microcosms with auriferous soils from semi-arid and tropical zones in Australia (Reith and McPhail, 2007). The solubilization of gold in the microcosms appeared to be linked to the activity of heterotrophic bacteria that dominate the bacterial communities in organic matter-rich soils. A mechanism for gold solubilization involving heterotrophic bacteria (that is, Bacillus subtilis, B. alvei, B. megaterium, B. mesentericus, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas fluorescens, P. liquefaciens and Bacterium nitrificans) has been described in earlier studies, where under in vitro conditions up to 35 mg l−1 (medium) of gold was solubilized as gold–amino acid complexes (Lyalikova and Mockeicheva, 1969; Korobushkina et al., 1974, 1976; Boyle, 1979; Korobushkina et al., 1983). DNA fingerprinting and assessment of the metabolic function of the bacterial community during the incubation of the microcosms, combined with gold and amino-acid analyses of the solution phase, indicated that the bacterial community changed from a carbohydrate- to amino acid-utilizing population concurrently with the solubilization and re-precipitation (Reith and McPhail, 2006). The bacterial community in the early stages of incubation (0–30 days) produced an overall excess of free amino acids, and up to 64.2 μM of free amino acids were measured in the soil solution within the first 30 days of incubation (Reith and McPhail, 2006). The bacterial community in the later stages of incubation (after 40–50 days) presumably metabolized these gold-complexing ligands (the concentration of free amino acids was reduced to ∼8.0 μM), and thus destabilized gold in solution, which led to the re-adsorption of gold to the solid soil fractions, and in particular the organic fraction (Reith and McPhail, 2006). These results suggest a link between gold solubilization and microbial turnover of amino acids in auriferous soils.

Concentration of solubilized gold in the solution in slurry microcosms (1 : 4 w/w soil to water) with Ah-horizon soil from the Tomakin Park Gold Mine in New South Wales, Australia, incubated biologically active or inactive (sterilized) for up to 90 days at 25 (diagram adapted from Reith and McPhail, 2006).

Another possible microbial mechanism for gold solubilization in auriferous soils is the oxidation and complexation of gold with cyanide (excreted by cyanogenic microbiota) leading to the formation of dicyanoaurate complexes (Au(CN)2−; Rodgers and Knowles, 1978; Saupe et al., 1982; Faramarzi et al., 2004; Faramarzi and Brandl, 2006):

At physiological pH, cyanide is mainly present as HCN and therefore volatile (Faramarzi and Brandl, 2006). However, in the presence of salts and cyanicidic compounds, for example metal ions, volatility is reduced, and thus cyanide produced by bacteria may directly affect gold solubilization in the environment (Faramarzi and Brandl, 2006). An in vitro study using the cyanogenic bacterium Chromobacterium violaceum demonstrated that biofilms grown on gold-covered glass slides were able to solubilize 100 wt% of gold within 17 days, with concentrations of gold and free cyanide in solution reaching 35 and 14.4 mg l−1 (medium), respectively (Campbell et al., 2001). Similar results were also obtained when C. violaceum was incubated with biooxidized gold ore concentrate; here up to 0.34 and 9 mg l−1 (medium) of gold and cyanide, respectively, were detected in solution within 10 days (Campbell et al., 2001). Pseudomonas plecoglossicida has been shown to solubilize 69% of gold from shredded printed circuit boards after 80 h of incubation, by producing up to 500 mg [Au(CN)2−] per litre (medium; Faramarzi and Brandl, 2006).

Cyanide production and excretion in soils has commonly been ascribed to higher plants and fungi, but is also widespread in soil bacteria, such as P. fluorescens, P. aeruginosa, P. putida, P. syringae and B. megaterium, which produce cyanide via the membrane-bound enzyme complex, HCN synthase (Knowles, 1976; Wissing and Andersen, 1981; Faramarzi et al., 2004; Faramarzi and Brandl, 2006). Cyanide has no apparent function in primary metabolism, is optimally produced during growth limitation and may offer the producer, which is usually cyanide tolerant, a selective advantage by inducing cyanide toxicity in other organisms, thus it can be classified as a typical secondary metabolite (Castric, 1975). Glycine is a common metabolic precursor for the microbial production of cyanide (Knowles, 1976; Rodgers and Knowles, 1978). The highest concentration of free glycine in solution in Tomakin Park Gold Mine soil microcosms was detected after 20 days of incubation (Reith and McPhail, 2006), and cyanide concentration up to 0.36 mg l−1 (soil solution) was measured in solution in recent Tomakin soil microcosms (F Reith, personal communication), suggesting that the solubilization of gold as dicyanoaurate complex, may occur in addition to gold solubilization with amino acids.

Overall, microbially mediated gold solubilization may occur as a consequence of the microbial production and excretion of a number of gold-complexing metabolites, that is, thiosulphate, amino acids and cyanide, in the presence of oxygen. Gold solubilization via the thiosulphate mechanism is expected in organic carbon matter-poor environments, where chemolithoautotrophic processes and populations dominate, for example, primary sulphide mineralization. Gold solubilization via the amino acid and/or cyanide mechanisms may occur in organic matter-rich top and rhizosphere soils, where plant root exudates may directly lead to gold solubilization. Root exudates also provide nutrients for resident microbiota, such as cyanogenic fungi and bacteria (for example, Pseudomonas sp.), which may further increase gold solubilization (Bakker and Schippers, 1987). These plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere may also lead to an increased uptake of gold by plants and/or contribute to the general dispersion of gold in the environment (Khan, 2005).

Bioaccumulation of gold by microorganisms

Laboratory studies have been conducted to elucidate the interactions of gold with microorganisms using gold(III) chloride- (Beveridge and Murray, 1976; Darnall et al., 1986; Greene et al., 1986; Watkins et al., 1987; Gee and Dudeney, 1988; Karamushka et al., 1990a, 1990b; Dyer et al., 1994; Southam and Beveridge, 1994, 1996; Canizal et al., 2001; Kashefi et al., 2001; Karthikeyan and Beveridge, 2002; Nair and Pradeep, 2002; Ahmad et al., 2003; Nakajima, 2003; Tsuruta, 2004; Keim and Farina, 2005; Lengke et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2006c, 2007; Reith et al., 2006), gold(I) thiosulphate- (Lengke and Southam, 2005, 2006, 2007; Lengke et al., 2006a), gold L-asparagine- (Southam et al., 2000), aurothiomalate-complexes (Higham et al., 1986) and colloidal gold-containing solutions (Karamushka et al., 1987b, 1990b; Ulberg et al., 1992). In study with 30 different microorganisms (eight bacteria, nine actinomycetes, eight fungi and five yeasts, Nakajima (2003) found that the bacteria were more efficient in removing gold(I/III) complexes from solution than other groups of microorganisms. These results were confirmed by Tsuruta (2004), who studied gold(III) chloride bioaccumulation in 75 different species (25 bacteria, 19 actinomycetes, 17 fungi and 14 yeasts), and found that gram-negative bacteria, such as Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and P. aeruginosa, had the highest ability to accumulate gold. Some bacteria also appear to be able to selectively and/or actively precipitate gold complexes, which suggests that gold bioaccumulation in these organisms may be part of a metabolic process, rather than passive biosorption that is often observed in fungi and algae (Savvaidis et al., 1998; Khoo and Ting, 2001; Nakajima, 2003; Figure 3). Some studies also point to different active, bioaccumulation mechanisms depending on whether the gold is extracellularly (that is, along the plasma or outer membranes; Figures 3a–c) or intracellularly (that is, in the cytoplasm, Figure 3d) precipitated, or accumulated in minerals or exopolymeric substances (Higham et al., 1986; Southam et al., 2000; Ahmad et al., 2003; Konishi et al., 2006; Lengke and Southam, 2006, 2007; Lengke et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2006c, 2007; Reith et al., 2006). These mechanisms may occur individually or in combination in different bacterial species (Higham et al., 1986; Lengke and Southam, 2006, 2007).

TEM micrographs of sulphate reducing (a), thiosulphate oxidising (b, c) and cyanobacteria (d) incubated in the presence of gold(I/III) complexes. (a) Desulfovibrio sp. encrusted with gold, as indicated by dark particles (after 148 days incubation at 25 °C with 500 p.p.m. gold as [Au(S2O3)23−]); (b, c) Thin sections of A. thiooxidans cells with nanoparticles of gold deposited along the outer wall layer, periplasm and cytoplasmic membrane (after 75 days incubation at 25 °C with 50 p.p.m. of gold as [Au(S2O3)23−]); (d) Thin section of P. boryanum showing nanoparticles of gold deposited inside cells (after 28 days incubation at 25 °C with 500 p.p.m. of gold as [AuCl4−]).

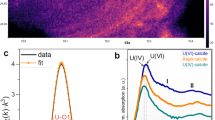

In the presence of H2 as electron donor the anaerobic Fe-reducing bacterium Shewanella algae has been shown to intracellularly precipitate metallic gold nanoparticles (Konishi et al., 2006). Intracellular gold precipitation was also shown in the cyanobacterium Plectonema boryanum (Lengke et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2006c; Figure 3d), and an alkalotolerant actinomycete (Rhodococcus sp.; Ahmad et al., 2003). The mechanisms of gold bioaccumulation by P. boryanum from gold(III) chloride solutions have been studied using XAS (Lengke et al., 2006c). The results show that the reduction mechanism of gold(III) chloride to metallic gold by the cyanobacterium involves the formation of an intermediate gold(I) species, similar to a gold(I) sulphide (Lengke et al., 2006c). The sulphur presumably originates from cysteine or methionine in cyanobacterial proteins or binding to glutathione (Fahey et al., 1978). Sporasarcina ureae was able to grow in the presence of up to 10 p.p.m. of gold complexed by L-asparagine, but not in the presence of gold(III) chloride (Southam et al., 2000). During growth with gold-L-asparagine, S. ureae did not precipitate metallic gold intracellularly; the intracellular immobilization was associated with the low molecular weight protein fraction, which appeared to regulate the detoxification (Southam et al., 2000). This suggests that the intracellular formation of gold nanoparticles may occur via an intermediate gold(I)–protein complex; the reduction of the intermediate complex to metallic gold may then be regulated by its concentration in the cell.

The intracellular precipitation and formation of gold nanoparticles (<10 nm) from gold(I) thiosulphate was also observed in SRB (that is, Desulfovibrio sp.; Lengke and Southam, 2006, 2007). In addition, the presence of localized reducing conditions produced by the bacterial electron transport chain via energy-generating reactions led to extracellular precipitation of gold, and the formation of hydrogen sulphide triggered iron sulphide formation, which caused removal of gold from solution by adsorption and reduction on iron sulphide surfaces (Lengke and Southam, 2006, 2007; Figure 3a). In earlier studies with B. subtilis, Beveridge and Murray (1976) have shown that the extracellular reduction and precipitation of gold from gold(III) chloride solution were selective, as similar processes did not occur for Ag(I). In solutions containing a combination of gold(III) chloride, Cu2+, Fe2+ and Zn2+, gold was selectively adsorbed by B. subtilis (Gee and Dudeney, 1988) and Spirulina platensis (Savvaidis et al., 1998). The extracellular accumulation of gold(III) chloride and colloidal gold in Bacillus sp. was further investigated by Ulberg et al. (1992) and Karamushka et al. (1987a, 1987b), who found that bioaccumulation of gold by Bacillus sp. depended on the chemical fine structure of the cell envelope, and involved functional groups of proteins and carbohydrates bound in the plasma membrane. In further studies, the accumulation of gold by Bacillus sp. was shown to be directly dependent on the metabolic activity of the cells, and particularly the hydrolysis of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) by the enzyme ATPase in the plasma membrane (Karamushka et al., 1990a, 1990b; Ulberg et al., 1992).

Gold accumulation in an exopolysaccharide capsule was observed in Hyphomonas adhaerens; cultures that were able to form the capsule-precipitated gold from gold(III) chloride solutions, whereas a mutant without capsule was not able to do so (Quintero et al., 2001). Gold accumulation in exopolymeric substances also played a role in the detoxification of gold(III) chloride by P. aeruginosa, which displayed a four times higher viability when grown as a biofilm (containing exopolymeric substances (EPS)) compared to free planktonic cells when subjected to 0.1 mM gold(III) chloride (Karthikeyan and Beveridge, 2002). Burkholderia cepecia has been shown to grow in the presence of 0.5–5 mM concentrations of gold(I) thiolates, such as aurothiomalate, using a number of apparent adaptation mechanisms (Higham et al., 1986). As a result, the size of cells increased, cells formed polyhydroxybutyrate granules, accumulated gold and excreted a low molecular weight protein called thiorin, which may have bound the gold complexes in the culture medium (Higham et al., 1986).

To summarize this section, bacteria are particularly efficient in accumulating gold complexes, and have developed a number of mechanisms that enable them to accumulate gold intra- or extracellularly, or in products of their metabolism, suggesting that this may lead to advantages for the survival of these bacterial populations.

Advantages of active gold bioaccumulation

The capability to actively accumulate gold using enzyme systems to deal with gold toxic complexes may result in advantages for the survival of microbial populations by being able to (1) detoxify the immediate cell environment, (2) use gold-complexing ligands to gain metabolic energy or (3) use gold as a micronutrient.

The mechanisms of gold toxicity in bacterial cells are little understood, but it is likely that gold complexes cause toxicity and cell death by disrupting the normal redox activity of cell membranes, and by affecting the permeability of cell walls and membranes by cleaving disulphide bonds in peptides and proteins (Witkiewicz and Shaw, 1981; Carotti et al., 2000; Karthikeyan and Beveridge, 2002). It is clear, however, that gold complexes are toxic to microorganisms at very low concentration, the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of gold(III) chloride in Escherichia coli is 20 μM (∼4 p.p.m.) and toxic effects to the organisms start at approximately 1/1000 of the MIC (Nies, 1999). Gold concentrations in soil solutions from auriferous soils can reach more than 100 p.p.b. (McPhail et al., 2006; Reith and McPhail, 2006), and are possibly even higher in solutions surrounding gold nuggets. Thus, toxic effects to microorganisms in these zones are likely to occur, and having developed mechanisms to detoxify the immediate cell environment would certainly mean a survival advantage.

For detoxification processes leading to the reductive precipitation of gold to occur, microorganisms need to able to detect, and subsequently reduce gold complexes. In bacteria, cytoplasmic metal ion-responsive transcriptional regulators are important in regulating the expression of genes involved in metal ion homoeostasis and efflux systems (Silver, 1996; Nies, 1999, 2003; Hobman, 2007). The MerR family of transcriptional activators are metal-sensing regulators that are found in a variety of bacteria and have a common design, but have evolved to recognize and respond to different metals (Silver, 1996; Nies, 1999, 2003; Hobman, 2007). In a study with E. coli, Stoyanov and Brown (2003) demonstrated for the first time the specific regulation of transcription by gold complexes. They showed that CueR, an MerR-like transcriptional activator that usually responds to Cu+, is also activated by gold complexes (presumably gold(III) chloride), and that this activation is promoted by specific binding of gold to the cysteine residues 112 and 120 (Cys 112 and 120). In a recent study Checa et al. (2007) characterized a new transcriptional regulator (GolS) in the bacterium Salmonella enterica. GolS shares with other MerR family regulators the metal-binding cysteine residues Cys112 and 120, but retains exclusive specificity to gold(III) chloride. The presence of at least two open reading frames whose expression is activated by GolS, one of which is a predicted transmembrane efflux ATPase (GolT), and the other a predicted metallochaperone (GolB), suggests a mechanism for resistance to gold complexes that is consistent with the organization of many metal resistances, where an MerR regulator controls both its own production and that of a P-type ATPase and a chaperone protein (Checa et al., 2007; Hobman, 2007).

The MerR family of regulators is also important in regulating metal resistance in C. metallidurans, with Rmet_3523, an apparent ortholog to GoIS, present in its genome (Nies and Silver, 1995; Mergeay et al., 2003; Socini FC, personal communication). C. metallidurans is associated with secondary gold grains, actively reduces gold complexes and accumulates native gold, and thus may provide a critical link between the precipitation of gold observed in the laboratory and the observed ‘bacterioform’ gold in natural systems (below; Reith et al., 2006). C. metallidurans is a gram-negative facultative chemolithoautotrophic β-proteobacterium, that is able to withstand high concentrations of heavy metal ions (for example, Cu, Pb, Zn, Cd, Ag and Au; Mergeay et al., 2003; Reith et al., 2006). Its extraordinary heavy metal resistance and ability to accumulate metals on its surface promoting detoxification hail from multiple layers of P-type ATPase efflux pumps activated by MerR-like regulator genes (Legatzki et al., 2003; Mergeay et al., 2003; Nies, 2003). A recent study of C. metallidurans strain CH34 has identified eight putative metal-transporting ATPases involved in metal binding compared with the average of three P1-ATPases in other microorganisms (Monchy et al., 2006).

Other gram-negative bacteria, such as P. boryanum, produce membrane vesicles that may act as protective shields against toxic metals (Silver, 1996). When P. boryanum faces high concentrations of [Au(S2O3)23−], the cells release membrane vesicles (Lengke et al., 2006a). These vesicles remain associated with the cell envelope, ‘coating’ the cells, which help prevent uptake of [Au(S2O3)23−], keeping it away from sensitive cellular components. The interaction of [Au(S2O3)23−] with the vesicle components causes the precipitation of elemental gold on the surfaces of the vesicles, possibly through the interaction with phosphorus, sulphur or nitrogen ligands from the vesicle components (Lengke et al., 2006a). Thus, bacteria like S. enterica, C. metallidurans and P. boryanum appear to have evolved effective mechanisms to detect and avoid gold toxicity, which will allow them to thrive in gold-rich environments.

The precipitation of gold from gold(I) thiosulphate solutions has been observed in the presence of thiosulphate-oxidizing bacteria (Figures 3b and c; A. thiooxidans; Lengke and Southam, 2005). The gold precipitated by A. thiooxidans was accumulated inside the bacterial cells as fine-grained colloids ranging between 5 and 10 nm in diameter and in the bulk fluid phase as crystalline micrometre-scale gold (Lengke and Southam, 2005). While gold was deposited throughout the cell, it was concentrated along the cytoplasmic membrane, suggesting that gold precipitation was likely enhanced via electron transport processes associated with energy generation (Figures 3b and c; Figure 4). When gold(I) thiosulphate entered the cells as a complex, thiosulphate was used in a metabolic process within the periplasmic space, and gold(I) was transported into the cytoplasm by the chemiosmotic gradient across the cytoplasmic membrane and/or through ATP hydrolysis. Since gold(I) cannot be degraded, gold(I) will form a new complex or be reduced to metallic gold(0). Metallic gold is potentially re-oxidized, forming a new complex, which can also be transported outside the cytoplasm (Figure 4).

Schematic model for [Au(S2O3)23−] utilization and gold precipitation by A. thiooxidans (adapted from Lengke and Southam, 2005). When [Au(S2O3)23−] is the only available energy source a pore in the outer membrane allows the exchange of sulphur species and gold. Sulphur reactions occur in the periplasmic space, while gold reduction process may occur in the cytoplasm. The oxidized sulphur and reduced gold are released as waste products through the outer membrane pore, which is a possible origin for gold observed inside and at bacterial cells.

Gold is believed to be non-essential for microbial nutrition (Madigan and Martinko, 2006). However, in the presence of gold, Micrococcus luteus has been shown to oxidize methane more efficiently by forming a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase that includes a gold(I/III)-redox couple in its active centre (Levchenko et al., 2000, 2002). This redox complex appears to activate methane by forming a CH3–gold(III) complex similar to methane-monooxygenase commonly used by methanotrophs (Levchenko et al., 2000). This may represent an alternative way for bacteria to utilize methane, but it is not known if other methanotrophic bacteria are able to form similar gold-containing enzymes, or if other gold-containing enzymes exist in any other microorganisms. However, in a recent study methanotrophs have been detected on secondary gold grains from an Australian mine, suggesting an environmental association of methane-oxidizing bacteria with gold (Reith, 2005).

To summarize, the general detoxification of gold complexes by bacteria is likely controlled by MerR-like regulators, which encode their own production, and that of P-type ATPases and chaperone proteins that transport gold out of the cells. Furthermore A. ferrooxidans has been shown to be able to utilize the gold thiosulphate complexes for energy generation, and a gold-containing enzyme involved in methane oxidation has been described in M. luteus.

Microbially mediated formation of secondary gold

The origin of coarse gold grains and nuggets has long been the subject of discussion among geologists studying placer deposits (Figure 5a). Three models have been established to explain their formation: detrital origin, chemical accretion and a combination of both (Boyle, 1979). One major problem is that gold grains in supergene environments are commonly coarser grained, that is, larger, than that observed in potential source rocks (Wilson, 1984; Watterson, 1992; Mossman et al., 1999). A second problem is the wide range of morphologies associated with secondary gold, which are not commonly observed in source ore deposits. These morphologies include wire, dendritic, octahedral, porous and sponge gold (Figure 5b; Kampf and Keller, 1982; Leicht, 1982; Lieber, 1982; Wilson, 1984; Watterson, 1992; Márquez-Zavalía et al., 2004). Hence, many authors have provided field-based evidence that secondary processes are responsible for their formation that occur mainly in soils or shallow regolith (Webster and Mann, 1984; Wilson, 1984; Clough and Craw, 1989; Watterson, 1992; Craw and Youngson, 1993; Lawrance and Griffin, 1994). Previous sections have shown that microbial gold solubilization and precipitation may occur in surficial environments. However, the extent and rate at which these secondary processes drive gold biomineralization, as opposed to purely abiotic secondary processes, is not clear.

Bioaccumulation of gold by microorganisms may lead to biomineralization of secondary gold. (a) An SEM micrograph of a secondary gold grain from the Tomakin Park Gold Mine (New South Wales, Australia); (b) SEM micrograph of octahedral gold platelets from cyanobacteria–AuCl4− experiments (after 28 days incubation at 25 °C with 500 p.p.m. of gold as [AuCl4−]); (c) SEM micrograph of a biofilm growing on a gold pellet incubated for 70 days in a biologically active slurry microcosms with soil from the Tomakin Park Gold Mine; (d) confocal microscopic images of a fluorescently stained (DAPI) biofilm on a secondary gold grain from the Hit or Miss Gold Mine (Queensland, Australia); (e, f) surface depression of gold grain extensively covered with a three-dimensional network of ‘bacteriofrom’ gold on a gold grain from the Hit or Miss Gold Mine; (g, h) detail of a rounded and budding cell pseudomorph forming ‘bacterioform’ gold from the Waimumu–Waikaka Quartz Gravels, New Zealand (adapted from Falconer et al., 2006).

Possible bacterial textures in secondary gold

Watterson (1992) first reported structures that resembled gold-encrusted microfossils on placer gold specimens from Lillian Creek in Alaska, and postulated a biological mechanism for the formation of gold grains. After studying 18 000 grains from different sites in Alaska and observing similar lace-like networks of micrometre-size filiform gold on the majority of these grains, he concluded that these gold grains were of bacterial origin (Watterson, 1992). He interpreted the observed structures as pseudomorphs of a Pedomicrobium-like budding organism. However, after producing analogous structures abiotically with natural and artificial gold amalgams using hot nitric acid dissolution, Watterson and others concluded that the observed morphologies alone could not be considered adequate evidence of microbial origin of these gold grains (Watterson, 1994; note, this geochemically extreme condition will not occur in placer environments).

Similar textures were detected on a wide variety of placer gold specimens that have not been subjected to any chemical treatment. Numerous specimens from different locations in Australia, South America and Canada have been studied, and many of the crevices in gold grains were covered by Pedomicrobium-like pseudomorphs similar to those described from the Alaskan specimens (Figures 5e and f; Bischoff et al., 1992; Mann, 1992; Keeling, 1993; Bischoff, 1994, 1997; Reith, 2005; Reith et al., 2006). Bud-like gold growths are common on the surfaces of authigenic gold from low-redox placer settings in southern New Zealand (Figures 5g and h; Falconer et al., 2006). These latter examples show a range of textures in a transition, with increasing mineralization, from isolated buds to coalesced buds to chains of buds and ultimately to infilled cavities (Falconer et al., 2006). Despite the apparent similarity of these buds to Pedomicrobium-like pseudomorphs, no direct connection between gold and bacteria had been established in the above examples.

Direct associations between secondary gold and bacteria

A recent study of untreated secondary gold grains from two field sites has provided this important link; using SEM and CSLM combined with nucleic acid staining, bacterial pseudomorphs and active bacterial biofilms, respectively, were revealed on the surfaces of these grains (Figures 5c and d; Reith et al., 2006). Molecular profiling showed that unique, site-specific bacterial communities are associated with gold grains that differ from those dominating the surrounding soils. 16S rDNA clones belonging to the genus Ralstonia and bearing a 99% similarity to C. metallidurans were present on all DNA-positive gold grains, but were not detected in the surrounding soils (Reith et al., 2006). The ability of C. metallidurans to actively accumulate gold from solution was successfully tested suggesting that C. metallidurans may contribute to the formation of secondary gold grains (Reith et al., 2006).

Octahedral plate-like secondary gold platelets are common in oxidized zones surrounding primary deposits (Figure 5b; Wilson, 1984; Lawrance and Griffin, 1994; Gray, 1998). Southam and Beveridge (1994, 1996) demonstrated the formation of metallic gold with octahedral habit by organic phosphate and sulphur compounds derived from bacteria at pH ∼2.6. The formation of metallic gold in phosphorus-, sulphur- and iron-containing granules within magnetotactic cocci has also been observed (Keim and Farina, 2005). Lengke et al. (2006a, 2006b, 2006c) observed octahedral gold, formed by P. boryanum at pH 1.9–2.2 and at 25–200 °C (Figure 5b). The bacteria, which were killed in this process, were able to intracellularily immobilize more than 100 μg mg−1 (d.w. bacteria; Figure 3d). In these systems, bacterial autolysis was initialized, proteins were released and pseudo-crystalline gold was formed, which was transformed into crystalline octahedral gold (up to 20 μM; Southam and Beveridge, 1994, 1996; Lengke et al., 2006a, 2006b). The ability of sulphur-oxidizing (Lengke and Southam, 2005) and -reducing (Lengke and Southam, 2006) bacteria to transform gold complexes into octahedral gold, suggests that bacteria contribute to the formation of gold platelets in the supergene environment (Figure 5b).

Secondary gold in quartz pebble conglomerates

Quartz pebble conglomerates are mature fluvial sedimentary rocks that commonly contain placer gold. The most famous auriferous QPC is the Archaean Witwatersrand sequence of South Africa (Frimmel et al., 1993; Minter et al., 1993), but similar younger deposits occur in California and New Zealand (Falconer et al., 2006; Youngson et al., 2006). Most QPC sequences contain detrital and authigenic sulphide minerals (Minter et al., 1993; Falconer et al., 2006). Authigenic sulphide and gold textures are well preserved in New Zealand QPCs, and also in the regionally metamorphosed Witwatersrand (Falconer et al., 2006). Bud-like authigenic gold morphologies that occur within New Zealand QPCs are similar in appearance to ‘filamentous’ gold that occurs in the Witwatersrand (Falconer et al., 2006). Notably, both QPC contain gold as an Au–Ag–Hg alloy and it is speculated that mercury from the Au–Ag–Hg alloy may play a significant role in the development of such ‘bacterioform’ textures (Falconer et al., 2006). In addition, a wide range of other authigenic gold textures occur, including octahedral and ‘triangular’ (pseudotrigonal octahedral) crystals and porous sheets (Clough and Craw, 1989; Falconer et al., 2006).

There is commonly a close association between secondary gold and organic matter in QPC sequences (Mossman et al., 1999; Falconer et al., 2006). This organic matter could have provided a suitable environment for bacteria to thrive, although no direct link has yet been established between authigenic gold and bacteria in these deposits. The carbonaceous matter, including solidified bitumen, associated with much of the gold in the Witwatersrand basin is thought to be of cyanobacterial origin primarily based on its isotopic composition (Hoefs and Schidlowski, 1967); however, it also possesses more contentious structural evidence of its bacterial origin due to the presence of filaments, which that are the size and shape of modern filamentous cyanobacteria (Dyer et al., 1984, 1994; Mossman and Dyer, 1985; Mossman et al., 1999). Alternatively, Spangenberg and Frimmel (2001) suggested that these filaments were introduced as liquid hydrocarbons, that is, diagenetic products of microbial origin. The occurrence of octahedral gold and diagenetic carbon suggests that these microbial products are also able to catalyse the formation of crystalline gold.

Conclusions and future directions

This review has shown that microorganisms are capable of actively solubilizing and precipitating gold, and suggests that they may play a key role in the dispersion and concentration of gold under surface conditions, in the deep subsurface and in hydrothermal zones (Figure 1). Results from recent studies provide experimental evidence for a number of genetic, biochemical and physiological mechanisms that microbes may use to drive biogeochemical gold cycling (Figure 1). These studies indicate that microorganisms (1) mediate gold solubilization via excretion of a number of metabolites (for example, thiosulphate, amino acids and cyanide); (2) have developed direct genomic and biochemical responses to deal with toxic gold complexes and (3) are able to precipitate gold intra- and extracellularly, and in products of their metabolism (for example, EPS and sulphide minerals). Bacteria such as S. enterica and C. metallidurans apparently use MerR-type gold-specific transcriptional regulators, which directly control detoxification via P-type ATPase efflux pumps and metal chaperone proteins. A. ferroooxidans gains metabolic energy by oxidizing thiosulphate from gold(I) thiosulphate complexes, and a gold-containing enzyme has been shown to improve methane oxidation in M. luteus. Bioaccumulation processes in C. metallidurans are possibly linked to the biomineralization of secondary ‘bacterioform’ gold. Sulphur-oxidizing and -reducing bacteria and cyanobacteria may be linked to the formation of secondary octahedral gold, and may have contributed to the formation of quartz pebble placer deposits.

While it is likely that many environmentally relevant groups of microbes may be involved in the biogeochemical cycling of gold, further experimental evidence for the proposed mechanisms needs to be obtained. The kinetics of gold-affecting processes in the environmental systems are little understood with respect to current environmental processes, and even less if geological times scales are taken into account. Furthermore, little is known about genomic and biochemical pathways leading to gold toxicity and detoxification in environmentally relevant organisms, nor has gold turnover been successfully linked to structures and activities of complex microbial communities in mineralized zones and auriferous soils. Thus, studies using genomic and proteomic approaches, such as RNA- and protein-expression arrays and quantitative PCR, have to be conducted to understand the biochemistry of gold turnover in different bacteria. Metagenomic and proteomic approaches in combination with field studies, microcosms and culturing studies may provide ways to link microbial community structures and activities with the turnover of gold in natural systems. Further synchrotron radiation-based experiments, such as μXRF, μXANES and μEFAXS of gold in individual cells need to be conducted to assess its distribution, speciation and association in cells. These studies may thus establish a direct link between the biogeochemical cycling of gold and microbial community activities, and provide a model for the assessment of other potential biogeochemical metal cycles, for example, Ag, Pt and Pd.

References

Ahmad A, Senapati S, Khan MI, Kumar R, Ramani R, Srinivas V et al. (2003). Intracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles by a novel alkalotolerant actinomycete, Rhodococcus species. Nanotechnol 14: 824–828.

Akob DM, Mills HJ, Kostka JE . (2007). Metabolically active microbial communities in uranium-contaminated subsurface sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 59: 95–107.

Aylmore MG, Muir DM . (2001). Thiosulfate leaching of gold—a review. Miner Eng 14: 135–174.

Baker BJ, Moser DP, MacGregor BJ, Fishbain S, Wagner M, Fry NK et al. (2003). Related assemblages of sulphate-reducing bacteria associated with ultradeep gold mines of South Africa and deep basalt aquifers of Washington State. Environ Microbiol 5: 267–277.

Baker WE . (1973). The role of humic acids from Tasmanian podzolic soils in mineral degradation and metal mobilization. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 37: 269–281.

Baker WE . (1978). The role of humic acids in the transport of gold. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 42: 645–649.

Bakker AW, Schippers B . (1987). Microbial cyanide production in the rhizosphere in relation to potato yield reduction and Pseudomonas spp-mediated plant growth-stimulation. Soil Biol Biochem 19: 451–457.

Barns SM, Fundyga RE, Jeffries MW, Pace NR . (1994). Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 1609–1613.

Barns SM, Nierzwicki-Bauer SA . (1997). Microbial diversity in ocean, surface, and subsurface environments. Rev Mineral 35: 35–79.

Benedetti M, Boulegue J . (1991). Mechanism of gold transfer and deposition in a supergene environment. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 55: 1539–1547.

Benning LG, Seward TM . (1996). Hydrosulfide complexing of Au(I) in hydrothermal solutions from 150–400 °C and 500–1500 bar. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60: 1849–1871.

Beveridge TJ, Murray RGE . (1976). Uptake and retention of metals by cell walls of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 127: 1502–1518.

Bischoff GCO . (1994). Gold-adsorbing bacteria as colonisers on alluvial placer gold. N Jb Geol Paläont Abh 194: 187–209.

Bischoff GCO . (1997). The biological origin of bacterioform gold from Australia. N Jb Geol Paläont Abh H 6: 329–338.

Bischoff GCO, Coenraads RR, Lusk J . (1992). Microbial accumulation of gold: an example from Venezuela. N Jb Geol Paläont Abh 194: 187–209.

Boyle RW . (1979). The geochemistry of gold and its deposits. Geol Surv Can Bull 280: 583.

Boyle RW, Alexander WM, Aslin GEM . (1975). Some Observations on the Solubility of Gold. Geological Survey of Canada Paper 75–24.

Bruins MR, Kapil S, Oehme FW . (2000). Microbial resistance to metals in the environment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 45: 198–207.

Campbell SC, Olson GJ, Clark TR, McFeters G . (2001). Biogenic production of cyanide and its application to gold recovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 26: 134–139.

Canizal G, Ascencio JA, Gardea-Torresday J, Yacaman MJ . (2001). Multiple twinned gold nanorods grown by bio-reduction techniques. Nanoparticle Res 3: 475–487.

Carotti S, Marcon G, Marussich M, Mazzei T, Messori L, Mini E et al. (2000). Cytotoxicity and DNA binding properties of a chloro-glycylhistidinate gold (III) complex (GhAu). Chem Biol Interact 125: 29–38.

Castric PA . (1975). Hydrogen cyanide, a secondary metabolite of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol 21: 613–618.

Checa SK, Espariz M, Pérez Audero ME, Botta PE, Spinelli SV, Soncini FC . (2007). Bacterial sensing of and resistance to gold salts. Mol Microbiol 63: 1307–1318.

Clough DM, Craw D . (1989). Authigenic gold-marcasite association- evidence for nugget growth by chemical accretion in fluvial gravels, Southland, New Zealand. Econ Geol 84: 953–958.

Craw D, Youngson JH . (1993). Eluvial gold placer formation on actively rising mountain ranges, Central Otago, New Zealand. Sed Geol 85: 623–635.

Csotonyi JT, Stackebrandt E, Yurkov V . (2006). Anaerobic respiration on tellurate and other metalloids in bacteria from hydrothermal vent fields in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 4950–4956.

Darnall DW, Greene B, Henzl MT, Hosea JM, McPherson RA, Sneddon J et al. (1986). Selective recovery of gold and other metal ions from algal biomass. Environ Sci Tech 20: 206–208.

DiChristina TJ, Fredrickson JK, Zachara JM . (2005). Enzymology of electron transport: energy generation with geochemical consequences. Rev Mineral Geochem 59: 27–52.

Donald R, Southam G . (1999). Low temperature anaerobic bacterial diagenesis of ferrous monosulfide to pyrite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 63: 2019–2023.

Dopson M, Baker-Austin C, Koppineedi PR, Bond PL . (2003). Growth in sulfidic mineral environments: metal resistance mechanisms in acidophilic micro-organisms. Microbiol 149: 1959–1970.

Druschel GK, Baker BJ, Gihring TH, Banfield JF . (2004). Acid mine drainage biogeochemistry at Iron Mountain, California. Geochem Trans 5: 13–32.

Dyer BD, Kretzschmar M, Krumbein WE . (1984). Possible microbial pathways in the formation of Precambrian ore deposits. J Geol Soc 141: 251–262.

Dyer BD, Krumbein WE, Mossman DJ . (1994). Nature and origin of stratiform kerogen seams in Lower Proterozoic Witwatersrand-type paleoplacers—the case for biogenicity. Geomicrobiol J 12: 91–98.

Edwards L, Kusel K, Drake H, Kostka JE . (2007). Electron flow in acidic subsurface sediments co-contaminated with nitrate and uranium. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 71: 643–654.

Ehrlich HL . (2002). Geomicrobiology. Marcel Dekker, Inc: New York, USA.

Enders MS, Southam G, Knickerbocker C, Titley SR . (2006). The role of microorganisms in the supergene environment of the Morenci porphyry copper deposit, Greenlee County, Arizona. Econ Geol 101: 59–70.

Fahey RC, Brown WC, Adams WB, Worsham MB . (1978). Occurrence of glutathione in bacteria. J Bacteriol 133: 1126–1129.

Falconer DM, Craw D, Youngson JH, Faure K . (2006). Gold and sulphide minerals in Tertiary quartz pebble conglomerate gold placers, Southland, New Zealand. In: Els BG, Eriksson PG (eds). Ore Geology Reviews 28, Special Issue: Placer Formation and Placer Minerals. pp 525–545.

Faramarzi MA, Brandl H . (2006). Formation of water-soluble metal cyanide complexes from solid minerals by Pseudomonas plecoglossicida. FEMS Microbiol Lett 259: 47–52.

Faramarzi MA, Stagars M, Pensini E, Krebs W, Brandl H . (2004). Metal solubilization from metal-containing solid materials by cyanogenic Chromobacterium violaceum. J Biotechnol 113: 321–326.

Farges F, Sharps JA, Brown Jr GE . (1991). Local environment around gold(III) in aqueous chloride solutions: an EXAFS spectroscopy study. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 57: 1243–1252.

Fetzer WG . (1934). Transportation of gold by organic solutions. Econ Geol 29: 599–604.

Fetzer WG . (1946). Humic acids and true organic acids as solvents of minerals. Econ Geol 41: 47–56.

Fisher EI, Fisher VL, Millar AD . (1974). Nature of the interaction of natural organic acids with gold. Sov Geo 7: 142–146.

Fitz RM, Cypionka H . (1990). Formation of thiosulfate and trithionate during sulfite reduction by washed cells of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Arch Microbiol 154: 400–406.

Fitzgerald WF, Lamborg CH, Hammerschmidt CR . (2007). Marine biogeochemical cycling of mercury. Chem Rev 107: 641–662.

Fredrickson JK, Balkwill DL . (2006). Geomicrobial processes and biodiversity in the deep terrestrial subsurface. Geomicrobiol J 23: 345–356.

Freise FW . (1931). The transportation of gold by organic underground solutions. Econ Geol 26: 421–431.

Friedrich CG, Bardischewsky F, Rother D, Quentmeier A, Fischer J . (2005). Prokaryotic sulfur oxidation. Curr Opin Microbiol 8: 1–7.

Frimmel HE, LeRoex AP, Knight J, Minter WE . (1993). A case study of the postdepositional alteration of Witwatersrand Basal Reef Gold Placer. Econ Geol 88: 249–265.

Gadd GM . (2004). Microbial influence on metal mobility and application for bioremediation. Geoderma 122: 109–119.

Gammons CH, Williams-Jones AE . (1997). Chemical mobility of gold in the porphyry-epithermal environment. Econ Geol 92: 45–59.

Gammons CH, Yu Y, Williams-Jones AE . (1997). The disproportionation of gold(I) chloride complexes at 25–200 °C. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61: 1971–1983.

Gee AR, Dudeney AWL . (1988). Adsorption and crystallization of gold on biological surfaces. In: Kelly DP, Norris PR (eds). Biohydrometallurgy. Science & Technology Letters: London, UK, pp 437–451.

Gilbert F, Pascal ML, Pichavant M . (1998). Gold solubility and speciation in hydrothermal solutions: experimental study of the stability of hydrosulfide complex of gold (AuHS) at 350–450 °C and 500 bars. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 62: 2931–2947.

Goldhaber MB . (1983). Experimental study of metastable sulphur oxyanion formation during pyrite oxidation at pH 6–9 and 30 °C. Am J Sci 283: 193–217.

Goldschmidt VM . (1954). Geochemistry. Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK.

Gray DJ . (1998). The aqueous chemistry of gold in the weathering environment. Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Evolution and Mineral Exploration, Open File Report, 38. Wembley West: Australia.

Gray DJ, Lintern MJ, Longman GD . (1998). Chemistry of gold-humic interactions. Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Evolution and Mineral Exploration, Open File Report, 43. Wembley West: Australia.

Greene B, Hosea M, McPherson R, Henzl M, Alexander MD, Darnall DW . (1986). Interaction of gold (I) and gold (III) complexes with algal biomass. Environ Sci Technol 20: 627–632.

Grosse C, Anton A, Hoffmann T, Franke S, Schleuder G, Nies DH . (2004). Identification of a regulatory pathway that controls the heavy-metal resistance Czc via promoter czcNp in Ralstonia metallidurans. Arch Microbiol 182: 109–118.

Handelsman J . (2004). Metagenomics: application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms Microbiol. Molecul Biol Rev 68: 669–685.

Higham DP, Sadler PJ, Scawen MD . (1986). Gold-resistant bacteria: excretion of cysteine-rich protein by Pseudomanas cepacia induced by antiarthritic drug. J Inorg Biochem 28: 253–261.

Hobman JL . (2007). MerR family transcription activators: similar designs different specifities. Mol Microbiol 65: 1275–1278.

Hoefs J, Schidlowski M . (1967). Carbon isotope composition of carbonaceous matter from the Precambrian of the Witwatersrand system. Science 155: 1096–1097.

Holden JF, Adams MWW . (2003). Microbe-metal interactions in marine hydrothermal environments. Cur Op Chem Biol 7: 160–165.

Housecroft CE . (1993). Gold. Coord Chem Rev 127: 187–221.

Housecroft CE . (1997a). Gold 1994. Coord Chem Rev 164: 161–182.

Housecroft CE . (1997b). Gold 1995. Coord Chem Rev 164: 667–691.

Inagaki F, Takai K, Komatsu T, Sakihama Y, Inoue A, Horikoshi K . (2002). Profile of microbial community structure and presence of endolithic microorganisms inside a deep-sea rock. Geomicrobiol J 19: 535–552.

Islam FS, Gault AG, Boothman C, Polya DA, Charnock JM, Chatterjee D et al. (2004). Role of metal-reducing bacteria in arsenic release from Bengal delta sediments. Nature 430: 68–71.

Jones B, Renault RW, Rosen MR . (2001). Biogenicity of gold- and silver-bearing siliceous sinters forming in hot (75 °C) anaerobic spring-waters of Champagne Pool, Waiotapu, North Island, New Zealand. J Geol Soc 158: 895–911.

Kampf AR, Keller PC . (1982). The Colorado quartz mine, Mariposa County, California: a modern source of crystallized gold. Miner Rec 13: 347–354.

Karamushka VI, Gruzina TG, Podolska VI, Ulberg ZR . (1987a). Interaction of glycoprotein of Bacillus pumilis cell wall with liposomes. Ukr Biokhim Zh 59: 70–75.

Karamushka VI, Gruzina TG, Ulberg ZR . (1990a). Effect of respiratory toxins on bacterial concentration of trivalent gold. Ukr Biokhim Zh 62: 103–105.

Karamushka VI, Ulberg ZR, Gruzina TG . (1990b). The role of membrane processes in bacterial accumulation of Au(III) and Au(0). Ukr Biokhim Zh 62: 76–82.

Karamushka VI, Ulberg ZR, Gruzina TG, Podolska VI, Pertsov NV . (1987b). Study of the role of surface structural components of microorganisms in heterocoagulation with colloidal gold particles. Pricl Biokhim Microbiol 23: 697–702.

Karthikeyan S, Beveridge TJ . (2002). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms react with and precipitate toxic soluble gold. Environ Microbiol 4: 667–675.

Kashefi K, Lovley DR . (2003). Extending the upper temperature limit for life. Science 301: 934.

Kashefi K, Tor JM, Nevin KP, Lovley D . (2001). Reductive precipitation of gold by dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria and archaea. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 3275–3279.

Keeling JR . (1993). Microbial influence in the growth of alluvial gold from Watts Gully, South Australia. South Aust Geol Surv Quart Geol N 126: 12–19.

Keim CN, Farina M . (2005). Gold and silver trapping by uncultured magnetotactic cocci. Geomicrobiol J 22: 55–63.

Khan AG . (2005). Role of soil microbes in the rhizosphere of plants growing on trace metal contaminated soils in phytoremediation. J Trace Elem Med and Biol 18: 355–364.

Khoo K, Ting Y . (2001). Biosorption of gold by immobilized fungal biomass. Biochem Eng J 8: 51–59.

King RJ . (2002). Arsenopyrite. Geol Today 18: 72–78.

Knowles CJ . (1976). Microorganisms and cyanide. Bacteriol Rev 40: 652–680.

Konishi Y, Tsukiyama T, Ohno K, Saitoh N, Nomura T, Nagamine S . (2006). Intracellular recovery of gold by microbial reduction of AuCl4− ions using the anaerobic bacterium Shewanella algae. Hydrometallurgy 81: 24–29.

Korobushkina ED, Chernyak AS, Mineyev GG . (1974). Dissolution of gold by microorganisms and products of their metabolism. Mikrobiologiia 43: 9–54.

Korobushkina ED, Karavaiko GI, Korobushkin IM . (1983). Biochemistry of gold. In: Hallberg R (ed). Environmental Biogeochemistry Ecol Bull, vol. 35. Stockholm: Sweden, pp 325–333.

Korobushkina ED, Mineyev GG, Praded GP . (1976). Mechanism of the microbiological process of dissolution of gold. Mikrobiologiia 45: 535–538.

Krauskopf KB . (1951). The solubility of gold. Econ Geol 46: 858–870.

Kunert J, Stransky Z . (1988). Thiosulfate production from cystine by the kerarinolytic prokaryote Streptomyces fradiae. Arch Micriobiol 150: 600–601.

Lawrance LM, Griffin BJ . (1994). Crystal features of supergene gold at Hannan South, Western Australia. Mineral Deposita 29: 391–398.

Legatzki A, Franke S, Lucke S, Hoffmann T, Anton A, Neumann D et al. (2003). First step towards a quantitative model describing Czc-mediated heavy metal resistance in Ralstonia metallidurans. Biodegradation 14: 153–168.

Leicht WC . (1982). California gold. Mineral Rec 13: 375–383, 386, 387.

Lengke MF, Fleet ME, Southam G . (2006a). Morphology of gold nanoparticles synthesized by filamentous cyanobacteria from gold(I)-thiosulfate and gold(III)-chloride complexes. Langmuir 22: 2780–2787.

Lengke MF, Fleet ME, Southam G . (2006b). Bioaccumulation of gold by filamentous cyanobacteria between 25 and 200 °C. Geomicrobiol J 23: 591–597.

Lengke MF, Ravel B, Fleet ME, Wanger G, Gordon RA, Southam G . (2006c). Mechanisms of gold bioaccumulation by filamentous cyanobacteria from gold(III)-chloride complex. Environ Sci Technol 40: 6304–6309.

Lengke MF, Ravel B, Fleet ME, Wanger G, Gordon RA, Southam G . (2007). Precipitation of gold by reaction of aqueous gold(III)-chloride with cyanobacteria at 25–80 °C, studied by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Can J Chem 85: 1–9.

Lengke MF, Southam G . (2005). The effect of thiosulfate-oxidizing bacteria on the stability of the gold-thiosulfate complex. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 69: 3759–3772.

Lengke MF, Southam G . (2006). Bioaccumulation of gold by sulfate-reducing bacteria cultured in the presence of gold(I)-thiosulfate complex. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70: 3646–3661.

Lengke MF, Southam G . (2007). The deposition of elemental gold from gold(I)-thiosulfate complex mediated by sulfate-reducing bacterial conditions. Econ Geol 102: 109–126.

Levchenko LA, Sadkov AP, Lariontseva NV, Koldasheva EM, Shilova AK, Shilov AE . (2000). Methane oxidation catalyzed by the Au-protein from Micrococcus luteus. Dokl Biochem Biophys 377: 123–124.

Levchenko LA, Sadkov AP, Lariontseva NV, Koldasheva EM, Shilova AK, Shilov AE . (2002). Gold helps bacteria to oxidize methane. J Inorg Biochem 88: 251–253.

Lieber W . (1982). European gold. Miner Rec 6: 359–364.

Lloyd JR . (2003). Microbial reduction of metals and radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27: 411–425.

Lyalikova NN, Mockeicheva LY . (1969). The role of bacteria in gold migration in deposits. Microbiol 38: 682–686.

Madigan MT, Martinko JM . (2006). Brock—Biology of Microorganisms, 11th edn. Prentice Hall: New York, USA.

Mann AW . (1984). Mobility of gold and silver in lateritic weathering profiles: some observations from Western Australia. Econ Geol 79: 38–50.

Mann S . (1992). Bacteria and the Midas touch. Nature 357: 358–360.

Márquez-Zavalía MF, Southam G, Craig JR, Galliski MA . (2004). Morphological and chemical study of placer gold from the San Luis Range, Argentina. Can Mineral 42: 55–68.

McHugh JB . (1988). Concentration of gold in natural waters. J Geochem Explor 30: 85–94.

McPhail DC, Usher A, Reith F . (2006). On the mobility of gold in the regolith: results and implications from experimental studies. In: Fitzpatrick RW, Shand P (eds). Proceeding of the CRC LEME Regolith Symposium. Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Environments and Mineral Exploration: Australia, pp 227–229.

Mergeay M, Monchy S, Vallaeys T, Auquier V, Benotmane A, Bertin P et al. (2003). Ralstonia metallidurans, a bacterium specifically adapted to toxic metals: towards a catalogue of metal-responsive genes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27: 385–410.

Mergeay M, Nies D, Schlegel HG, Gerits J, Charles P, van Gijsegem F . (1985). Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J Bacteriol 162: 328–334.

Mielke RE, Pace DL, Porter T, Southam G . (2003). A critical stage in the formation of acid mine drainage: colonization of pyrite by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans under pH neutral conditions. Geobiol 1: 81–90.

Mineyev GG . (1976). Organisms in the gold migration-accumulation cycle. Geokhimiya 13: 577–582.

Minter MG, Knight J, Frimmel HE . (1993). Morphology of Witwatersrand gold grains from the basal reef: evidence for their detrital origin. Econ Geol 88: 237–248.

Monchy S, Vallaeys T, Bossus A, Mergeay M . (2006). Metal transport ATPase genes from Cupriavidus metalliduransCH34: a transcriptomic approach. Int J Environ Anal Chem 86: 677–692.

Morteani G . (1999) In: Schmidbaur H (ed). Gold: Progress in Chemistry, Biochemistry and Technology. Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, Chapter 2.

Moser DP, Gihring TM, Brockman FJ, Fredrickson JK, Balkwill DL, Dollhopf ME et al. (2005). Desulfotomaculum spp. and Methanobacterium spp. dominate 4–5 km deep fault. Appl Environ Microbiol 12: 8773–8783.

Mossman DJ, Dyer BD . (1985). The geochemistry of Witwatersrand-type gold deposits and the possible influence of ancient prokaryotic communities on gold dissolution and precipitation. Precamb Res 30: 303–319.

Mossman DJ, Reimer T, Durstling H . (1999). Microbial processes in gold migration and deposition: modern analogues to ancient deposits. Geosci Can 26: 131–140.

Nair B, Pradeep T . (2002). Coalescence of nanoclusters and formation of submicron crystallites assisted by Lactobacillus strains. Crystal Growth Des 2: 293–298.

Nakajima A . (2003). Accumulation of gold by microorganisms. WJ Microbiol Biotechn 19: 369–374.

Navarro-González R, Rainey FA, Molina P, Bagaley DR, Hollen BJ, de la Rosa J et al. (2003). Mars-like soils in the Atacama desert, Chile, and the dry limit of microbial life. Science 302: 1018–1021.

Nelson KE, Methé B . (2005). Metabolism and genomics: adventures derived from complete genome sequencing. Rev Mineral Geochem 59: 279–294.

Newman DK, Banfield JF . (2002). Geomicrobiology: how molecular-scale interactions underpin biogeochemical systems. Science 296: 1071–1077.

Nies DH . (1992). CzcR and CzcD, gene products a!ecting regulation of resistance to cobalt, zinc and cadmium (czc system) in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol 174: 8102–8110.

Nies DH . (1995). The cobalt, zinc, and cadmium efflux system CzcABC from Alcaligenes eutrophus functions as a cation-protonantiporter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 177: 2707–2712.

Nies DH . (1999). Microbial heavy metal resistance. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 51: 730–750.

Nies DH . (2003). Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27: 313–339.

Nies DH, Brown NL . (1998). Two-component systems in the regulation of heavy metal resistance. In: Silver S, Walden W (eds). Metal Ions in Gene Regulation. Chapman and Hall: London. pp 77–103.

Nies DH, Silver S . (1995). Ion efflux systems involved in bacterial metal resistances. J Indust Microbiol Biotechnol 14: 186–199.

Nordstrom DK, Southam G . (1997). Geomicrobiology of sulfide metal oxidation. Rev Mineral 35: 361–390.

Ong HL, Swanson VE . (1969). Natural organic acids in the transportation, deposition and concentration of gold. Colo Sch Mines, Q 64: 395–425.

Pan P, Wood SA . (1991). Gold-chloride in very acidic aqueous solution and at temperature 25–300 °C: a laser Raman spectroscopic study. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 55: 2365–2371.

Phoenix VR, Renaut RW, Jones B, Ferris FG . (2005). Bacterial S-layer preservation and rare arsenic-antimony-sulphide bioimmobilization in siliceous sediments from Champagne Pool hot spring, Waiotapu, New Zealand. J Geol Soc 162: 323–331.

Poole RK, Gadd GM . (1989). Metal-Microbe Interaction. IRL Press: Oxford, UK.

Quintero EJ, Langille SE, Weiner RM . (2001). The polar polysaccharide capsule of Hyphomonas adhaerens MHS-3 has a strong affinity for gold. J Indust Microbiol Biotech 27: 1–4.