Abstract

Salivary analysis can be used to assess the severity of caries. Of the known salivary proteins, a paucity of information exists concerning the role of proteinase 3 (PR3), a serine protease of the chymotrypsin family, in dental caries. Whole, unstimulated saliva was collected from children with varying degrees of active caries and tested using a Human Protease Array Kit and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A significantly decreased concentration of salivary PR3 was noted with increasing severity of dental caries (P<0.01); a positive correlation (r=0.87; P<0.01; Pearson’s correlation analysis) was also observed between salivary pH and PR3 concentration. In an antibacterial test, a PR3 concentration of 250 ng·mL−1 or higher significantly inhibited Streptococcus mutans UA159 growth after 12 h of incubation (P<0.05). These studies indicate that PR3 is a salivary factor associated with the severity of dental caries, as suggested by the negative relationship between salivary PR3 concentration and the severity of caries as well as the susceptibility of S. mutans to PR3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most common human diseases, with a high prevalence of caries in early mixed dentition worldwide. Caries can progress rapidly if left untreated, resulting in pain and infection; thus, early diagnosis and prevention is of great importance.1,2,3,4,5 Salivary analyses have been used to help assess the risk of caries by measuring the saliva’s buffering capacity and bacterial content.6 Recent studies have also indicated that a comprehensive compositional analysis of the complexity of oral fluid is very important in the assessment of the severity of caries.1,7,8

Whole saliva is predominantly composed of water (99.5%); it also contains proteins (0.3%) and inorganic, trace substances (0.2%).9 The origin and function of some salivary proteins (e.g., α-amylase, carbonic anhydrase, cystatins, statherins, histatins and proline-rich proteins) and inorganic compounds have been studied, but those of salivary proteases have yet to be fully elucidated.6,9,10

The word ‘protease’ refers to any enzyme that catalyses proteolysis reactions. Different classes of proteases can perform the same reaction via completely different catalytic mechanisms.11,12 In the oral cavity, proteases are derived from bacteria or are secreted by human glands. Proteases can also originate from the oropharyngeal mucosae and crevicular fluids.7,9 Such enzymes play many varied but important roles in metabolic control, making any analysis of proteases in the oral cavity meaningful.

Several recent studies have indicated that people with caries display high levels of salivary matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8).13,14 Nevertheless, this does not preclude other proteases from associations with caries, including another significant oral protease, proteinase 3 (PR3). A serine protease of the chymotrypsin family, PR3 is stored in the primary granules of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and is implicated in a variety of infectious inflammatory diseases, such as lung disease, as well as non-infectious inflammatory processes such as glomerulonephritis, arthritis and bullous pemphigoid.15,16,17,18,19 However, the role of PR3 in cariology is presently unknown.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to investigate the association of salivary proteases with caries in Chengdu, China, particularly in 6-year-old children with differing degrees of dental caries. More specifically, we analysed the role of PR3 in dental caries and its effect on Streptococcus mutans, a component of the normal flora of the human mouth that is commonly associated with dental caries.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All human saliva samples were collected from 6-year-old children attending Yong’an kindergarten in Chengdu, China, under the approved guidelines of Sichuan University, China. Written informed consent for children who participated in the experimental investigation was obtained from their guardians. The study and consent procedures were approved by the Ethics Committees of West China Hospital of Stomatology and State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, both of Sichuan University, China.

Data and sample collection

A total of 128 healthy children with and without caries, from Yong’an kindergarten, were included in this study. Each child was examined under natural light with the aid of a dental mirror and probe. World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria were used in determining decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing teeth (due to caries) and filled teeth (DMFT/deft) indices.

Children were divided into three groups according to the severity of dental caries:8 no dental caries (NDC) group, consisting of 46 children; low dental caries (LDC) group with a DMFT/deft of 1–4, consisting of 49 children; and high dental caries (HDC) group with a DMFT/deft of 5–15, consisting of 33 children.

All subjects were instructed to refrain from eating and drinking for 12 h prior to saliva collection and to brush their teeth in the morning. Up to 5 mL of fasting, unstimulated, whole saliva was collected between 8:00 and 10:00.

After collection, the saliva specimens were kept on ice and immediately taken to the laboratory. Samples were centrifuged at 1000g for 2 min, and the supernatants were stored at −80 °C until use.

Protease array and image analysis

In this study, 1 mL of donor saliva supernatant from each participant in the NDC group and 1 mL of donor saliva supernatant from each participant in the HDC group were tested using a Human Protease Array Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), which measures the relative protein expression of 34 human proteases (each protease contains a pair of pot in one membrane). For image analysis, X-ray film was scanned with a CanoScan LiDE 700F (Canon, Beijing, China) and analysed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

PR3 concentration assay

Salivary PR3 concentrations in all the 128 donors were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cloud-Clone C, Wuhan, China). The product of the PR3 concentration was analysed spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 450 nm. The results were analysed using a Varioskan Flash Multimode Reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Measurement of pH

The pH of each saliva sample was tested using a SevenEasy S20 pH meter (Shanghai Joystech Environmental Protection Technology, Shanghai, China).

Antibacterial test

Human PR3 (Cloud-Clone, Wuhan, China) was purchased. A freshly prepared microbial (Streptococcus mutans UA159) suspension (diluted to an optical density (OD) value of 0.2) and brain–heart infusion (BHI) medium were pipetted into a 96-well microtiter plate (20 µL microbial suspension and 80 µL BHI medium per well). To a plate with eight rows, sterile phosphate buffer solution (PBS) was added to the first row (100 µL per well) as the control. Two-fold serial dilutions of PR3 solution were then made, with concentrations ranging from 2 000 to 31.5 ng·mL−1; then, these dilutions were added to the remaining seven rows. Each mixed solution used in the bacterial test contained 20 µL bacterial suspension, 80 µL BHI medium and 100 µL PR3 (or PBS control) solution per well. A final concentration range of PR3 from 15.75 to 1 000 ng·mL−1 was used. Each plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, after which the OD value of each mixed solution was measured at 600 nm every 3 h using a Varioskan Flash Multimode Reader. Three replicates were used in the test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS19.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Numerical data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The difference between the means was analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

The state of caries at Yong’an kindergarten is presented in Table 1. The mean prevalence of caries in subjects was 64.06%. The mean DMFT/dmft for the total group was 2.39±2.89, with females showing significantly lower values than males (P=0.19). The mean DMFT/dmft for the LDC and HDC groups was 1.98+0.83 and 6.33+2.76, respectively, and the difference between these groups was significant (P<0.01).

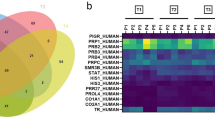

The protease array results suggested that the pixel density of MMP-8 for the NDC group was significantly lower than that for the HDC group (Figure 1; P<0.01). In contrast, the pixel density of PR3 for the NDC group was significantly higher than that for the HDC group (Figure 1; P<0.01).

Protease array. (a) Human protease array membrane for one saliva supernatant sample from the NDC group. (b) Human protease array membrane for one saliva supernatant sample from the HDC group. (c) Mean pixel density of MMP-8 and PR3. The pixel density of MMP-8 in the NDC group (Figure 1a, n=1) was lower than that in the HDC group (Figure 1b, n=1). The pixel density of PR3 in the NDC group was significantly higher than that in the HDC group. **P<0.01 as determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by a post-hoc Tukey's test. ANOVA, analysis of variance; HDC, high dental caries; MMP, metalloproteinase; NDC, no dental caries; PR3, proteinase 3.

We next measured the PR3 concentration between the three groups (NDC, LDC, HDC) and found them to be significantly different (P=0.009; an overall P value). Compared to the mean concentration of PR3 for the NDC group (17.82±7.31) ng·mL−1, those for the LDC group (12.79±6.19) ng·mL−1 and HDC group (11.07±7.10) ng·mL−1 were significant lower (Figure 2a; P=0.02 and P=0.003, respectively, vs. NDC group). However, we did not find a significant difference between the LDC and HDC groups (Figure 2a; P=0.434), based on the mean PR3 concentration. Between the genders (male (14.63±6.69) ng·mL−1; female (13.52±8.52) ng·mL−1, we found no significant difference (P=0.574) in the concentration of PR3 (Figure 2b). There was also no significant overall difference (P=0.13) in the mean pH values of saliva from the three groups (Figure 2c; NDC group, pH=7.13±0.23, n=46; LDC group, pH=7.02±0.30, n=49; HDC group, pH= 6.96±0.25, n=33). No significant difference (P=0.23) was observed between the pH values of saliva from males and females (results not shown). However, there was a positive correlation between saliva pH and PR3 concentration (Figure 2d; r=0.87; P<0.01; Pearson’s correlation analysis).

PR3 concentration and pH of saliva from different severities of dental caries. (a) PR3 concentration in different severities of dental caries. The mean PR3 concentration in the LDC group (12.79±6.19) ng·mL−1 and HDC group (11.07±7.10) ng·mL−1 was significantly lower than that in the NDC group (17.82±7.31) ng.mL−1 as measured by ELISA. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 as determined by one-way ANOVA, followed by a post-hoc Tukey's test. (b) Concentration of PR3 in males and females. No significant difference (P=0.574) in PR3 concentration was observed between males and females. (c) Saliva pH in different severities of dental caries. There was no significant overall difference (P=0.13) in the mean pH values of saliva from the three groups (NDC group, pH=7.13±0.23, n=46; LDC group, pH=7.02±0.30, n=49; HDC group, pH=6.96±0.25, n=33). (d) The correlation between PR3 and pH. There was a positive correlation (r=0.87; P<0.01; Pearson's correlation analysis) between salivary pH values and PR3 concentration. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HDC, high dental caries; LDC, low dental caries; NDC, no dental caries; PR3, proteinase 3.

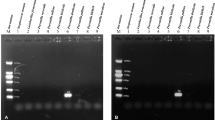

With regard to the susceptibility of S. mutans to PR3, there was no significant difference (P>0.05) in OD values between any groups with a PR3 concentration between 15.75 and 125 ng·mL−1 after 24 h of incubation (results not shown). However, when the concentration of PR3 was increased to 250 ng·mL−1 or above, a significant difference in OD values of S. mutans was noted after 12 h of incubation onwards (Figure 3; P<0.05).

Antibacterial properties of PR3 towards S. mutans. The OD of mixed solutions of differing PR3 concentrations and S. mutans (0, 250, 500 and 1 000 ng·mL−1) was measured every 3 h for 24 h. There was a significant difference (P<0.05; one-way ANOVA, followed by a post-hoc Tukey's test) in OD values between the groups after 12 h of incubation. Compared with the control group (0 ng·mL−1), the higher the concentration of PR3, the lower the OD values of S. mutans. OD, optical density; PR3, proteinase 3.

Discussion

Human saliva contains a large array of proteases that have important biological functions.1 Examining the differences in protease levels under different physiological conditions or pathologic states, using a new approach, may help us to better assess oral and systemic diseases.1,9

We found the total mean DMFT/dmft value in our study was 2.39±2.89, indicating a low-level caries severity according to WHO standards.20 The prevalence of caries in our study was 64.06%, similar to a report from the Namakkal District in India;21 however, the prevalence of caries in England, Finland and the USA is lower, at 4%, 6% and 20.2%, respectively, than in our study.22 These results highlight the overwhelming need for oral health education among pre-school children to be taken seriously by both parents and kindergartens, especially in outlying, poverty-stricken areas.23,24 As a result, the development and implementation of oral health promotion strategies is highly recommended.21,25

The protease array results suggested that the level of MMP-8 within saliva samples from subjects with caries was higher than that in subjects without caries. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which indicated that the presence of caries correlates strongly with salivary levels of MMP-8.26 It has been reported that MMPs play an important role in dental caries pathogenesis because collagen degradation is thought to be initiated by MMPs.14,27 However, the levels of salivary PR3 and other proteases in caries were noted to be lower in a caries-free environment, and an explanation for this observation has been lacking to date.

The known biological functions of PR3 include the following: degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components;28 cleavage of inflammatory mediators;29 platelet activation;30 induction of endothelial cell apoptosis;31 negative feedback regulation of granulopoiesis;32 and the target of auto-antibodies in Wegener’s granulomatosis.33 Previous studies have not described any known relationship between PR3 and dental caries. As shown with ELISA, we found that children who were caries-resistant, whether they were male or female, demonstrated higher PR3 concentrations in their saliva; conversely, the more serious the caries, the lower the concentration of PR3. This suggests that PR3 may act as a protease factor in the severity of dental caries, with low levels leading to a greater severity of caries. Thus, analysis of PR3 levels may help to assess the severity of caries.

The pH of whole saliva was also measured in this study. Caries-free children produced saliva with a slightly higher pH level than children with severe dental caries. In support of this finding, a report by Kuriakose et al.34 showed that the pH of saliva from children who suffered from rampant dental caries was significantly lower than that from children who were caries resistant. In our study, however, no significant overall difference was observed after comparing the three groups of differing severities of dental caries. This result suggests that using salivary pH on its own may not be useful for evaluating the severity of dental caries and that salivary pH should be considered in conjunction with dental plaque or other components in the oral cavity.35,36

It has been reported that the optimal pH for PR3 activity is 8.0.15,37 In our study, a significantly positive correlation was shown between PR3 concentration and pH, with higher pH leading to increased PR3 concentration. In the oral cavity, an alkaline environment may be more conducive to enzyme activity by PR3 or other proteases.15

The bactericidal mechanism of PR3 was also studied.38,39 Previous findings indicated that PR3 has an extracellular, microbicidal role in neutrophil extracellular traps.39 PR3 can also process human cathelicidin (hCAP-18) to generate the potent, antibacterial 4.5 kDa peptide LL-37.40 Some reports have even suggested that PR3 can defend against fungal infections.41 However, the role of PR3 in cariology is presently unknown. Our data confirm that S. mutans, part of the oral flora associated with dental caries, are also susceptible to PR3. This susceptibility may be mediated by a bacteriostatic effect or an effect on bacterial growth. When the concentration of PR3 was increased to 250 ng·mL−1 or above, bacterial growth was significantly inhibited after 12 h of incubation. However, the PR3 concentration in the oral cavity is approximately 3–30 ng·mL−1; thus, further study is required to determine whether the PR3 concentration can reach 250 ng·mL−1 or above in the human oral cavity. Thus, additional studies are required to explore the physiological significance of the concentration of PR3 required to inhibit bacterial growth and to determine whether PR3 can be used as a preventive measure for dental caries in clinical trials.

In conclusion, our analyses utilizing protease arrays and ELISAs indicate that the protease PR3 is associated with the severity of dental caries, with low levels being associated with a greater severity of caries. Moreover, our antibacterial test results showed that S. mutans is susceptible to PR3.

References

Schipper RG, Silletti E, Vingerhoeds MH . Saliva as research material: biochemical, physicochemical and practical aspects. Arch Oral Biol 2007 ; 52 ( 12 ) : 1114 – 1135 .

Smith GA, Riedford K . Epidemiology of early childhood caries: clinical application. J Pediatr Nurs 2013 ; 28 ( 4 ) : 369 – 373 .

Ng MW, Ramos-Gomez F, Lieberman M et al . Disease management of early childhood caries: ECC Collaborative Project. Int J Dent 2014 ; 2014 : 327801 .

Ng MW, Ramos-Gomez F . Disease prevention and management of early childhood caries. J Mass Dent Soc 2012 ; 61 ( 3 ) : 28 – 32 .

Ai JY, Smith B, Wong DT . Bioinformatics advances in saliva diagnostics. Int J Oral Sci 2012 ; 4 ( 2 ) : 85 – 87 .

Van Nieuw Amerongen A, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC . Salivary proteins: protective and diagnostic value in cariology? Caries Res 2004 ; 38 ( 3 ) : 247 – 253 .

Lima DP, Diniz DG, Moimaz SA et al . Saliva: reflection of the body. Int J Infect Dis 2010 ; 14 ( 3 ) : e184 – e188 .

Kirtaniya BC, Chawla HS, Tiwari A et al . Natural prevalence of antibody titres to GTF of S. mutans in saliva in high and low caries active children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2009 ; 27 ( 3 ) : 135 – 138 .

Chiappin S, Antonelli G, Gatti R et al . Saliva specimen: a new laboratory tool for diagnostic and basic investigation. Clin Chim Acta 2007 ; 383 ( 1/2 ) : 30 – 40 .

Helmerhorst EJ, Oppenheim FG . Saliva: a dynamic proteome. J Dent Res 2007 ; 86 ( 8 ) : 680 – 693 .

Chaudhry AS . Comparing two commercial enzymes to estimate in vitro proteolysis of purified or semi-purified proteins. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr : Berl 2005 ; 89 ( 11/12 ) : 403 – 412 .

Boudida Y, Gagaoua M, Becila S et al . Serine protease inhibitors as good predictors of meat tenderness: which are they and what are their functions? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2014 ; doi:10.1080/10408398.2012.741630. [Epub ahead of print].

Nascimento FD, Minciotti CL, Geraldeli S et al . Cysteine cathepsins in human carious dentin. J Dent Res 2011 ; 90 ( 4 ) : 506 – 511 .

Sorsa T, Tjäderhane L, Salo T . Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in oral diseases. Oral Dis 2004 ; 10 ( 6 ) : 311 – 318 .

Korkmaz B, Horwitz MS, Jenne DE et al . Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Pharmacol Rev 2010 ; 62 ( 4 ) : 726 – 759 .

Korkmaz B, Lesner A, Letast S et al . Neutrophil proteinase 3 and dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C) as pharmacological targets in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis). Semin Immunopathol 2013 ; 35 ( 4 ) : 411 – 421 .

Guarino C, Legowska M, Epinette C et al . New selective peptidyl di(chlorophenyl) phosphonate esters for visualizing and blocking neutrophil proteinase 3 in human diseases. J Biol Chem 2014 ; 289 ( 46 ) : 31777 – 31791 .

Schrijver G, Schalkwijk J, Robben JC et al . Antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis in beige mice. Deficiency of leukocytic neutral proteinases prevents the induction of albuminuria in the heterologous phase. J Exp Med 1989 ; 169 ( 4 ) : 1435 – 1448 .

Liu Z, Shapiro SD, Zhou X et al . A critical role for neutrophil elastase in experimental bullous pemphigoid. J Clin Invest 2000 ; 105 ( 1 ) : 113 – 123 .

Al-Darwish M, El Ansari W, Bener A . Prevalence of dental caries among 12-14 year old children in Qatar. Saudi Dent J 2014 ; 26 ( 3 ) : 115 – 125 .

Karunakaran R, Somasundaram S, Gawthaman M et al . Prevalence of dental caries among school-going children in Namakkal district: A cross-sectional study . J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2014 ; 6 ( Suppl 1 ) : S160 – S161 .

Vadiakas G . Case definition, aetiology and risk assessment of early childhood caries (ECC): a revisited review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2008 ; 9 ( 3 ) : 114 – 125 .

Wigen TI, Wang NJ . Caries and background factors in Norwegian and immigrant 5-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2010 ; 38 ( 1 ) : 19 – 28 .

Feldens CA, Vítolo MR, Drachler Mde L . A randomized trial of the effectiveness of home visits in preventing early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007 ; 35 ( 3 ) : 215 – 223 .

Ashley P, Di Iorio A, Cole E et al . Oral health of elite athletes and association with performance: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2014 ; 49 ( 1 ) : 14 – 19 .

Hedenbjörk-Lager A, Bjørndal L, Gustafsson A et al . Caries correlates strongly to salivary levels of matrix metalloproteinase-8. Caries Res 2014 ; 49 ( 1 ) : 1 – 8 .

Solovykh EA, Karaoglanova TB, Kushlinskii NE et al . Matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory cytokines in the oral fluid of patients with chronic generalized periodontitis various structural materials restoration of teeth and dentition . Klin Lab Diagn 2013 ; ( 10 ): 55 – 58 .

Rao NV, Wehner NG, Marshall BC et al . Characterization of proteinase-3 (PR-3), a neutrophil serine proteinase. Structural and functional properties. J Biol Chem 1991 ; 266 ( 15 ) : 9540 – 9548 .

Sugiyama A, Uehara A, Iki K et al . Activation of human gingival epithelial cells by cell-surface components of black-pigmented bacteria: augmentation of production of interleukin-8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1. J Med Microbiol 2002 ; 51 ( 1 ) : 27 – 33 .

Renesto P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Nusbaum P et al . Proteinase 3. A neutrophil proteinase with activity on platelets. J Immunol 1994 ; 152 ( 9 ) : 4612 – 4617 .

Yang JJ, Preston GA, Pendergraft WF et al . Internalization of proteinase 3 is concomitant with endothelial cell apoptosis and internalization of myeloperoxidase with generation of intracellular oxidants. Am J Pathol 2001 ; 158 ( 2 ) : 581 – 592 .

Bories D, Raynal MC, Solomon DH et al . Down-regulation of a serine protease, myeloblastin, causes growth arrest and differentiation of promyelocytic leukemia cells. Cell 1989 ; 59 ( 6 ) : 959 – 968 .

Jennette JC, Hoidal JR, Falk RJ . Specificity of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies for proteinase 3. Blood 1990 ; 75 ( 11 ) : 2263 – 2264 .

Kuriakose S, Sundaresan C, Mathai V et al . A comparative study of salivary buffering capacity, flow rate, resting pH, and salivary Immunoglobulin A in children with rampant caries and caries-resistant children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2013 ; 31 ( 2 ) : 69 – 73 .

Animireddy D, Reddy Bekkem VT, Vallala P et al . Evaluation of pH, buffering capacity, viscosity and flow rate levels of saliva in caries-free, minimal caries and nursing caries children: An in vivo study . Contemp Clin Dent 2014 ; 5 ( 3 ): 324 – 328 .

Raner E, Lindqvist L, Johansson S et al . pH and bacterial profile of dental plaque in children and adults of a low caries population. Anaerobe 2014 ; 27 : 64 – 70 .

Baici A, Szedlacsek SE, Früh H et al . pH-dependent hysteretic behaviour of human myeloblastin (leucocyte proteinase 3) . Biochem J 1996 ; 317 ( Pt 3 ): 901 – 905 .

Gabay JE, Scott RW, Campanelli D et al . Antibiotic proteins of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989 ; 86 ( 14 ): 5610 – 5614 .

Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C et al . Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004 ; 303 ( 5663 ) : 1532 – 1535 .

Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH et al . Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood 2001 ; 97 ( 12 ) : 3951 – 3959 .

Tkalcevic J, Novelli M, Phylactides M et al . Impaired immunity and enhanced resistance to endotoxin in the absence of neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G . Immunity 2000 ; 12 ( 2 ) : 201 – 210 .

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81372892), Sichuan Province Science and Technology Innovation Team Program (JCPT 2011-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

This license allows readers to copy, distribute and transmit the Contribution as long as it is attributed back to the author. Readers may not alter, transform or build upon the Contribution, or use the article for commercial purposes. Please read the full license for further details at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, TY., Zhou, WJ., Du, Y. et al. Role of saliva proteinase 3 in dental caries. Int J Oral Sci 7, 174–178 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2015.8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2015.8