Abstract

Background:

Several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated associations between periconceptional environmental exposures and health status of the offspring in later life. Although these environmentally related effects have been attributed to epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation shifts at imprinted genes, little is known about the potential effects of maternal and paternal preconceptional overnutrition or obesity.

Objective:

We examined parental preconceptional obesity in relation to DNA methylation profiles at multiple human imprinted genes important in normal growth and development, such as: maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3), mesoderm-specific transcript (MEST), paternally expressed gene 3 (PEG3), pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1), epsilon sarcoglycan and paternally expressed gene 10 (SGCE/PEG10) and neuronatin (NNAT).

Methods:

We measured methylation percentages at the differentially methylated regions (DMRs) by bisulfite pyrosequencing in DNA extracted from umbilical cord blood leukocytes of 92 newborns. Preconceptional obesity, defined as BMI ⩾30 kg m−2, was ascertained through standardized questionnaires.

Results:

After adjusting for potential confounders and cluster effects, paternal obesity was significantly associated with lower methylation levels at the MEST (β=−2.57; s.e.=0.95; P=0.008), PEG3 (β=−1.71; s.e.=0.61; P=0.005) and NNAT (β=−3.59; s.e.=1.76; P=0.04) DMRs. Changes related to maternal obesity detected at other loci were as follows: β-coefficient was +2.58 (s.e.=1.00; P=0.01) at the PLAGL1 DMR and −3.42 (s.e.=1.69; P=0.04) at the MEG3 DMR.

Conclusion:

We found altered methylation outcomes at multiple imprint regulatory regions in children born to obese parents, compared with children born to non-obese parents. In spite of the small sample size, our data suggest a preconceptional influence of parental life-style or overnutrition on the (re)programming of imprint marks during gametogenesis and early development. More specifically, the significant and independent association between paternal obesity and the offspring’s methylation status suggests the susceptibility of the developing sperm for environmental insults. The acquired imprint instability may be carried onto the next generation and increase the risk for chronic diseases in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiologic studies, some with long-term follow-up, have demonstrated the importance of periconceptional nutrition of the mother as a crucial factor for optimal development and the long-term health status of the next generation. Early developmental exposures to maternal undernutrition or conditions of famine have been related to coronary heart disorders,1 increased body mass index (BMI),2, 3 hypertension,3, 4 elevated lipid profiles in female offspring,5 higher risk for breast cancer6 and mental health problems7 in later life. These observations have led to concepts of ‘developmental programming through intrauterine exposures or maternal nutrition’ and are consistent with Barker’s ‘thrifty phenotype hypothesis’.8 The transgenerational effects of poor fetal nutrition have in part been attributed to epigenetic changes at imprinted genes, among which there are persistent shifts in DNA methylation.9, 10 However, the effects of overnutrition are less understood. It is widely accepted that the current ‘westernized’ diet, characterized by high caloric intake and imbalanced nutritional supply, contributes to adverse health effects in the individual, although the effects on the next generation are poorly understood. Epidemiologic and animal studies indicate an association between preconceptional maternal obesity or overnutrition and cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, congenital abnormalities11, 12, 13 and behavioral problems, such as autism14 and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder,15 in the offspring. El Hajj and Haff16 demonstrated aberrant methylation at the mesoderm-specific transcript (MEST) imprinted gene in newborns from mothers suffering gestational diabetes; and research in animal models recently showed that methylation is affected at the imprinted paternally expressed gene 3 (PEG3) in oocytes from obese mice.17 Although the notion of ‘the developmental programming through nutritional exposures’ is confined to maternal exposures only, the paternal impact has not yet been studied in humans. A handful of studies in animal models suggest that preconceptional nutritional conditions of the father may alter metabolic mechanisms in the offspring.18, 19, 20 Earlier analysis of the Newborn Epigenetics STudy (NEST) subcohort revealed for the first time in humans that paternal BMI may also contribute to the offspring’s epigenetic profile. Lower methylation was observed at the IGF2 differentially methylated region (DMR) in children from obese fathers, compared with children from non-obese fathers.21 DMRs are regions of the genome at which multiple adjacent CpG sites show parent-of-origin-specific methylation. Genomic imprinting is defined by expression from either the paternal or the maternal allele. The imprint methylation marks at DMRs are established during gametogenesis, hence we hypothesize that the paternal allele is also susceptible to environmentally induced modifications or damage during sperm development. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the possible effects of parental obesity on DNA methylation at seven imprinted DMRs in NEST newborns, and hence evaluate an extended version of Barker’s hypothesis, namely that nutrition of both parents before conception is important in the developmental programming of the future child. In this analysis we included human imprinted genes involved in early growth regulation, such as MEST, PEG3 , pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1), epsilon sarcoglycan and paternally expressed gene 10 (SGCE/PEG10), neuronatin (NNAT) and maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3). The latter includes two DMRs: one located at the intergenic region between Delta-like 1 homolog (DLK1) and MEG3 (referred as the MEG3-IG DMR), and one located at the MEG3 promoter (referred as the MEG3 DMR). Deregulated expression of either of these genes has been associated with enlarged adipocyte size,22 obesity23 or several tumor types.24, 25, 26, 27

Subjects and methods

Study participants

Our study includes the first 98 children who enrolled in the prospective cohort NEST, born between July 2005 and November 2006 at Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC, USA. Recruitment strategies have been described in detail elsewhere.21, 28 In brief, English-speaking pregnant women, who were at least 18 years old and intending to use one of the two obstetric facilities in Durham County, NC, for their obstetric care were recruited by a trained interviewer at the prenatal clinics. Mothers self-administered a questionnaire and were helped by a trained nurse, if needed. Questionnaire data included socio-demographic information (for example, race/ethnicity and education), lifestyle characteristics (cigarette smoking) and detailed anthropometrics (the mother’s and the father’s height, highest and lowest weight ever, and current and usual weight). Medical records were abstracted to verify medical conditions, birth weight and the newborn’s gender. BMI was calculated from the data obtained from maternal or paternal heights and the mother’s weight before pregnancy or the father’s current weight; obesity was defined as BMI ⩾30 kg m−2. Our analytical study cohort includes only newborns from whom we obtained either maternal or paternal BMI. Of the 98 infants, 6 participants had missing height or weight information; hence, our study population includes a total of 92 newborns. Seventy-eight mothers (86%) provided detailed information about the biological fathers. One mother gave birth to twins, bringing the total number of newborns with matching paternal data to 79. The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Specimen collection

The umbilical vein was punctured, and cord blood samples were collected within minutes of delivery in a vacuum blood collection tube, coated with K3EDTA. The tubes were inverted gently to mix the anticoagulant with the blood. After centrifugation, the leukocyte-containing buffy coat was isolated and stored at −80 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted using Gentra Puregene Reagents (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

DNA methylation analysis

Bisulfite pyrosequencing assay development and validation have been previously described.29, 30 Methylation at CpG sites was quantitatively measured at seven DMRs. These DMRs included two involved in regulating the DLK1/MEG3 imprinted domain on chromosome 14q32.2 (the MEG3-IG DMR and the MEG3 DMR), one within the MEST promoter at 7q32.2, one at the NNAT locus at 20q11.23, one within the PEG3 promoter region at 19q13.43, one at the PLAGL1 locus at 6q24.2 and one at the SGCE/PEG10 promoter region at 7q21.3. The number of CpG sites studied at each DMR is depicted in Table 2. Genomic DNA (800 ng) was treated with sodium bisulfite, using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils, leaving methylated cytosines unchanged. Bisulfite-converted DNA (40 ng) was amplified by PCR using the PyroMark PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Specific positions of the primers used have been published earlier.29, 30 Pyrosequencing was performed in duplicate using a Pyromark Q96 MD pyrosequencing instrument (Qiagen). Of the 92 DNA samples, methylation data were complete for 83 subjects at the MEG3-IG DMR, 86 subjects at the MEG3 DMR, 84 subjects at the MEST DMR, 75 subjects at the NNAT DMR, 84 subjects at the PEG3 DMR, 82 subjects at the PLAGL1 DMR and 84 subjects at the SGCE/PEG10 DMR.

Statistical methods

Variables were defined as follows: marital status (living with partner or married versus single), obtained a college degree or not (high education versus low education), maternal age (<30 and ⩾30), race/ethnicity (African American, Caucasian and other or not specified), gestation time/age (<37 weeks and ⩾37 weeks), maternal smoking status (never/quit smoking when pregnant/continued smoking during pregnancy), gender of the baby (male or female), birth weight of the baby (<2.5 kg versus ⩾2.5 kg) and pre-pregnancy maternal or paternal obesity (<30 versus ⩾30 kg m−2) or BMI (Table 1).

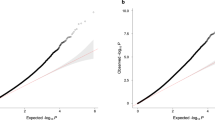

We computed the least square means (or estimated marginal means) of the methylation percentages at each CpG site, accounting for potential effects from multiple laboratory tests on different plates, wells and dates. In order to take into account potential cluster effects, we used mixed models, where well numbers and dates were included as random effects. The methylation outcomes for children born to non-obese parents are presented in Table 2 and were used as a baseline in Figure 1, where differences in methylation percentage by obesity of either of the parents were computed. For further assessment of the effects of maternal and/or paternal obesity on the methylation levels at each DMR we used multivariate procedures, adjusting for potential confounding and accounting for cluster effects from same person and experimental unit, as well as the covariance at the individual CpGs (Table 3). DNA methylation was the dependent variable, and parental obesity (or BMI) and co-variables were included as described above. Potential confounders were selected on the basis of known or observed associations with DNA methylation at these or other loci and with maternal or paternal obesity. A comparison of the different multivariate analyses, with exclusion or inclusion of most of our variables, did not change our results. We further explored the effects of parental obesity by race and repeated the multivariate analyses in Caucasians and African Americans. However, our statistical power calculations indicated that a stratified analysis represents unstable estimates, caused by the small numbers of obese parents by race. All analyses were based on the available laboratory data for each CpG site at the DMRs. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Changes in DNA methylation percentage at the DMRs of imprinted genes by parental obesity. Difference in methylation percentages between children born from obese parents compared with non-obese parents are shown by CpG site for each DMR studied, adjusted for cluster effects. The methylation percentages at baseline, representing the outcome for non-obese parents, are shown in Table 2. Bars represent s.e.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

About 32% of the newborns were born to mothers who were obese before pregnancy, whereas only 20% were born from a father reported as obese; in 12% both parents were obese. Maternal and paternal preconceptional obesity was strongly associated: the odds ratio was 4.9 (95% CI=1.5–15.9). The distributions of the characteristics of the study participants by parental obesity status are shown in Table 1. A little over 50% of the mothers were younger than 30 years old, independent of the obesity subgroup studied. Nearly 43% of the obese mothers were single, whereas only 12% were single in the non-obese subgroup (P=0.001). Maternal obesity was also strongly associated with race: most obese mothers were African American (71%), and most non-obese mothers were Caucasian (73%) (P<0.001). Although not statistically significant, 68% of the obese mothers had no college degree at the time of pregnancy, whereas 49% had not earned a college degree in the non-obese subgroup (P=0.10). Similarly, a non-significant inverse association was found between maternal obesity and smoking: 65% of the obese mothers never smoked, whereas only 44% reported ‘never smoking’ in the non-obese subgroup (P=0.11). About 90% of the pregnancies were full-term (gestation time was ⩾37 weeks). Approximately 17% of the newborns had a birth weight lower than 2.5 kg, and gender was equally distributed. Only one child was conceived using assisted reproductive technology, the parents were not obese (data not shown). Paternal obesity was not associated with any of the included characteristics, with the exception of maternal obesity, as described above.

Methylation levels at imprinted genes by obesity of the parents

Methylation profiles of newborns with non-obese parents are presented in Table 2, by individual CpG sites at each DMR studied. The calculated changes related to maternal or paternal obesity are shown in Figure 1. At the PLAGL1 DMR, we measured a mean methylation percentage of 59.8% for children born to non-obese parents; and if the mother was obese, an increase of 3.9% in DNA methylation was detected (s.e.=1.6, P=0.01). At the PEG3 DMR, children born to non-obese parents showed a mean methylation of 37.5%, and if the father was obese, a decrease of 1.5% was detected (s.e.=0.6; P=0.02). A mean methylation change of −1.9% was also measured at the MEST DMR of children born to obese fathers, although this was not significant (s.e.=1.0; P=0.07).

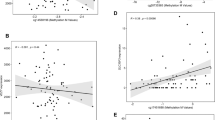

To determine the independent effects of preconceptional maternal or paternal obesity on offspring DNA methylation at the seven DMRs of the imprinted genes studied, we controlled for potential confounding owing to maternal age, smoking, education, newborn’s gender and race/ethnicity, in addition to experimental batch effects and the different CpGs studied. We found significant associations between paternal obesity and lower DNA methylation at MEST (P=0.003), NNAT (P=0.04) and PEG3 (P=0.007) (model 1, Table 3); whereas maternal obesity was associated with an increase in methylation at PLAGL1 (P=0.0005) and a borderline decrease in methylation at MEG3 (P=0.06) (model 2, Table 3). Notably, adding both maternal and paternal obesity in the model did not markedly change our results with regard to the exposure through the father, suggesting that the effects of paternal obesity are generally independent from the maternal exposures. If the newborn’s father was obese, the β-coefficient for MEST was −2.57 (P=0.008), the β-coefficient for NNAT was −3.59 (P=0.04) and the β-coefficient for PEG3 was −1.71 (P=0.005) (model 3, Table 3). At PLAGL1, the individual effect of maternal obesity showed an increase in methylation, with a β-coefficient of +2.58 (P=0.01) (model 3, Table 3). Furthermore, maternal obesity was associated with a decrease in methylation at MEG3: the β-coefficient was −3.42 (P=0.04) (model 3, Table 3). At the same locus, an opposite effect was seen in children from obese fathers, with a β-coefficient of +2.75 (P=0.11), but this was not significant.

We further extended our analyses by replacing the dichotomous obesity variable by the continuous BMI variable and found similar results. For instance, after controlling for the same variables as before, our model 3 showed that paternal BMI was related with a decrease in DNA methylation at the MEST DMR, β-coefficient was −0.16 (P=0.01); and at the PEG3 DMR, β-coefficient was −0.10 (P=0.03). Although an increase in DNA methylation at the SGCE/PEG10 DMR was positively associated with paternal BMI, β-coefficient was +0.12 (P=0.04). In general, maternal BMI did not affect DNA methylation, with one exception at the PLAGL1 DMR, where β-coefficient was +0.13 (P=0.01). These results confirm our findings when using the dichotomous obesity variable with a cutoff at 30 kg m−2. However, we lost significance at the NNAT DMR for paternal BMI and at the MEG3 DMR for maternal BMI, β-coefficients were −0.13 (P=0.32) and +0.01 (P=0.91), respectively.

Discussion

We hypothesized that not only in utero exposures but also preconceptional exposures through the father may induce epigenetic shifts at DMRs of imprinted genes in the offspring. Our key finding is that newborns from obese fathers are hypomethylated at the MEST, PEG3 and NNAT DMRs, independent of maternal obesity and other potential confounders. Obesity in mothers was associated with an increase in methylation at the PLAGL1 DMR and a decrease at the MEG DMR. When using pre-pregnancy BMI instead of obesity in our multivariate models, we also found a decrease in DNA methylation at the MEST and PEG3 DMRs by paternal BMI and a positive association between DNA methylation at the PLAGL1 DMR and maternal BMI. Our analyses further revealed a positive association between DNA methylation at the SGCE/PEG10 DMR and paternal BMI, suggesting that the effect can go either way (hypo- or hypermethylation), depending on the DMR studied.

Our results are consistent with our earlier findings on the IGF2 DMR, where differences in DNA methylation were detected in children from obese fathers or mothers.21 Although not reported here, we repeated the experimental analyses on the IGF2/H19 DMRs in a subset of the study population and were able to reconfirm these trends in methylation changes. Although alterations are subtle, methylation differences of similar magnitude have been reported earlier, inclusive of studies on in utero or periconceptional exposures to nutritional deprivation,31 folate supplements,28, 32 gestational diabetes,33 tobacco use34 and maternal use of medications including antidepressants35 and antibiotics.36 In general, changes in DNA methylation at imprint regulatory regions or loss of imprinting may persist through life37 and have been correlated with cardiovascular diseases,38, 39 behavioral disorders,40, 41 ovarian cancer,42 cervical cancer,30 Wilms’ tumor43, 44 and colorectal cancer.45, 46 These health defects were mainly related with IGF2 deregulation, but loss of imprinting or abnormal regulation of MEST and PEG3 has also been associated with cancer such as rhabdomyosarcoma27 and glioma.26 Loss of expression of the PLAGL1 gene, which was hypermethylated in children from obese mothers, has been detected in basal cell carcinoma,47 breast cancer,48 head and neck cancer,49 and ovarian tumors.50 Interestingly, PLAGL1, MEST and PEG3, which normally exhibit imprinting with silencing (or methylation) of the maternal allele and expression of the paternal allele, belong to a network of imprinted genes important in embryonic growth that are mainly expressed when rapid body growth is important, during embryogenesis and early postnatal life.51, 52, 53 It has been suggested that alteration of one member of the network may modulate the expression of several other imprinted genes in this network, leading to several imprinting-related pathologies.54 MEST and PEG3 are additionally involved in social behavioral phenotypes such as nest-building and lactation in mice.55 Studies in mouse models suggest that demethylation of the MEST promoter may lead to overexpression of the gene, causing enlargement of adipocytes and enhanced expression of genes related to metabolic conditions, such as diabetes or deficiencies in energy-uptake regulation.22 NNAT, also found to be hypomethylated in offspring from obese fathers, has also been associated with adipocyte and metabolic regulation, as well as with childhood obesity.23 Follow-up of the NEST population over time will further elucidate potential associations between paternal obesity and phenotypes in these children, such as obesity, diabetes or other disorders. Of note, after adjusting for potential confounders, our regression analyses indicated an inverse but insignificant effect of parental obesity on the MEG3 DMR (Table 3). Loss of imprinting at this locus has also been correlated with tumorigenesis.56

In general, the literature supports the idea that maternal lifestyle is important for optimal development of the fetus.57 Few epidemiologic studies have investigated the potential influence of paternal lifestyle or body composition on the next generation. Figueroa-Colon et al.58 showed that the paternal body fat may be a predictor for percentage of body fat in the offspring. Long-term cohort studies show that overeating before puberty may increase the risk of death from cardiovascular disease or diabetes in the grandchildren; this transgenerational association was only detected through the male line.59 Paternal obesity and metabolic effects in the offspring were also studied in the Framingham Heart Study, where aberrant levels of circulating alanine transaminase, a biomarker for liver function and risk for obesity, were measured in offspring from obese fathers.60 Observations in animal models are in line with the theory of a paternal impact on the next generation’s gene expression regulation or its metabolism. High-fat diet in male rats results in offspring with altered methylation at a putative regulatory region of the Interleukin 13 receptor alpha 2 gene and impaired insulin secretion.19 Similarly, Wu and Suzuki61 showed that parental high-fat diet before pregnancy was associated with aberrant fat accumulation in the rat offspring; although they did not distinguish between maternal and paternal diet, they suggested that high-fat diet may alter the parent’s insulin and glucose metabolism, causing an incomplete erasure of epigenetic marks during gametogenesis in associated genes. Other imbalanced diets, such as a low protein diet in male mice, resulted in changes in hepatic expression of genes involved in lipid and cholesterol biosynthesis.20 Similarly, paternal food deprivation in mice affected metabolism-related factors in the offspring, represented by low levels of serum glucose.18 The obesity burden and concomitant health problems are global issues. Male obesity interferes with fertility and sperm quality, but these can be bypassed with artificial reproductive techniques regardless of potential obesity-induced epigenetic changes. Our study cohort included only one child conceived through artificial reproductive techniques; in this particular case, parents were not obese. Our cohort further included one pair of twins. In order to exclude any potential epigenetic effects of either of these subjects, we repeated our analyses by eliminating twins and/or the child conceived through artificial reproductive techniques. Our findings were unaltered when analyses were restricted to non-twins and/or children not conceived through any artificial reproductive techniques.

The main limitation of our study is its small sample size; however, we explored multiple DMRs and found results that were consistent with our earlier report,21 suggesting that the paternal impact is strong enough to be detected in this small study cohort, whereas an association with maternal obesity is probably more complex and needs a larger sample size and alternative cohort(s) for appropriate evaluation. Other potential concerns are proof of paternity and the fact that paternal anthropometric data were reported by the mothers. However, we do not expect that the methylation outcomes are differential with respect to potential misclassification of these exposures. Consideration should also be given to the ethnicity of our population. Missing paternal data were most prominent among African American women and mothers with lower education. Hence, future studies should address the effects by racial/ethnic groups and level of education. A potential limitation of our study includes also the use of cord blood, with its differential cell counts, as a marker for the newborn’s epigenetic status. However, we used isolated leukocytes, and the epigenetic profile of imprinted genes is expected to be similar across all cell types. We earlier verified the DMR methylation profiles in several cell fractions of umbilical cord blood and found no significant differences across blood fractions at imprinted gene DMRs examined here.29

Despite the limitations, our results suggest that preconceptional parental lifestyle, or body fat composition, may cause transgenerational epigenetic effects. Although the underlying molecular processes are yet unclear, we believe that the conditions associated with obesity, such as elevated hormone levels, insulin resistance or diabetes, not measured in this study, may affect the epigenetic machinery at the level of the developing germ cells, finally causing DNA methylation shifts in the offspring. Further research is necessary to understand the biological mechanisms or targets of obesity-related exposures during gametogenesis, especially in the male germ line. We hypothesize that aside from earlier described maternal effects, also paternally induced modifications in epigenetic patterns may increase the susceptibility for diseases in the offspring at later age.

References

Painter RC, de Rooij SR, Bossuyt PM, Simmers TA, Osmond C, Barker DJ et al. Early onset of coronary artery disease after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 322–327 (quiz 466–7).

Ravelli GP, Stein ZA, Susser MW . Obesity in young men after famine exposure in utero and early infancy. N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 349–353.

Huang C, Li Z, Wang M, Martorell R . Early life exposure to the 1959-1961 Chinese famine has long-term health consequences. J Nutr 2010; 140: 1874–1878.

Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JH, Ravelli AC, van Montfrans GA, Osmond C, Barker DJ et al. Blood pressure in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. J Hypertens 1999; 17: 325–330.

Lumey LH, Stein AD, Kahn HS, Romijn JA . Lipid profiles in middle-aged men and women after famine exposure during gestation: the Dutch Hunger Winter Families Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 1737–1743.

Painter RC, De Rooij SR, Bossuyt PM, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Bleker OP et al. A possible link between prenatal exposure to famine and breast cancer: a preliminary study. Am J Hum Biol 2006; 18: 853–856.

Huang C, Phillips MR, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z et al. Malnutrition in early life and adult mental health: Evidence from a natural experiment. Soc Sci Med 2013; 97: 259–266.

Hales CN, Barker DJ . The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull 2001; 60: 5–20.

Waterland RA, Jirtle RL . Early nutrition, epigenetic changes at transposons and imprinted genes, and enhanced susceptibility to adult chronic diseases. Nutrition 2004; 20: 63–68.

Jirtle RL, Skinner MK . Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet 2007; 8: 253–262.

Drake AJ, Reynolds RM . Impact of maternal obesity on offspring obesity and cardiometabolic disease risk. Reproduction 2010; 140: 387–398.

Dyer JS, Rosenfeld CR . Metabolic imprinting by prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal overnutrition: a review. Semin Reprod Med 2011; 29: 266–276.

Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, Rankin J . Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 301: 636–650.

Krakowiak P, Walker CK, Bremer AA, Baker AS, Ozonoff S, Hansen RL et al. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 2012; 129: e1121–e1128.

Rodriguez A, Miettunen J, Henriksen TB, Olsen J, Obel C, Taanila A et al. Maternal adiposity prior to pregnancy is associated with ADHD symptoms in offspring: evidence from three prospective pregnancy cohorts. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 550–557.

El Hajj N, Haaf T . Epigenetic disturbances in in vitro cultured gametes and embryos: implications for human assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril 2013; 99: 632–641.

Ge ZJ, Liang XW, Guo L, Liang QX, Luo SM, Wang YP et al. Maternal diabetes causes alterations of DNA methylation statuses of some imprinted genes in murine oocytes. Biol Reprod 2013; 88: 117.

Anderson LM, Riffle L, Wilson R, Travlos GS, Lubomirski MS, Alvord WG . Preconceptional fasting of fathers alters serum glucose in offspring of mice. Nutrition 2006; 22: 327–331.

Ng SF, Lin RC, Laybutt DR, Barres R, Owens JA, Morris MJ . Chronic high-fat diet in fathers programs β-cell dysfunction in female rat offspring. Nature 2010; 467: 963–966.

Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, Shea JM, Hart CE, Li R et al. Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals. Cell 2010; 143: 1084–1096.

Soubry A, Schildkraut JM, Murtha A, Wang F, Huang Z, Bernal A et al. Paternal obesity is associated with IGF2 hypomethylation in newborns: results from a Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) cohort. BMC Med 2013; 11: 29.

Takahashi M, Kamei Y, Ezaki O . Mest/Peg1 imprinted gene enlarges adipocytes and is a marker of adipocyte size. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005; 288: E117–E124.

Vrang N, Meyre D, Froguel P, Jelsing J, Tang-Christensen M, Vatin V et al. The imprinted gene neuronatin is regulated by metabolic status and associated with obesity. Obesity 2010; 18: 1289–1296.

Zhao J, Dahle D, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A . Hypermethylation of the promoter region is associated with the loss of MEG3 gene expression in human pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90: 2179–2186.

Gejman R, Batista DL, Zhong Y, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Swearingen B et al. Selective loss of MEG3 expression and intergenic differentially methylated region hypermethylation in the MEG3/DLK1 locus in human clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 4119–4125.

Otsuka S, Maegawa S, Takamura A, Kamitani H, Watanabe T, Oshimura M et al. Aberrant promoter methylation and expression of the imprinted PEG3 gene in glioma. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2009; 85: 157–165.

Rezvani G, Lui JC, Barnes KM, Baron J . A set of imprinted genes required for normal body growth also promotes growth of rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Pediatr Res 2012; 71: 32–38.

Hoyo C, Murtha AP, Schildkraut JM, Forman MR, Calingaert B, Demark-Wahnefried W et al. Folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy in the Newborn Epigenetics STudy (NEST). BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 46.

Murphy SK, Huang Z, Hoyo C . Differentially methylated regions of imprinted genes in prenatal, perinatal and postnatal human tissues. PLoS One 2012; 7: e40924.

Nye MD, Hoyo C, Huang Z, Vidal AC, Wang F, Overcash F et al. Associations between methylation of paternally expressed gene 3 (PEG3), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cervical cancer. PLoS One 2013; 8: e56325.

Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 17046–17049.

Steegers-Theunissen RP, Obermann-Borst SA, Kremer D, Lindemans J, Siebel C, Steegers EA et al. Periconceptional maternal folic acid use of 400 microg per day is related to increased methylation of the IGF2 gene in the very young child. PLoS One 2009; 4: e7845.

El Hajj N, Pliushch G, Schneider E, Dittrich M, Muller T, Korenkov M et al. Metabolic programming of MEST DNA methylation by intrauterine exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1320–1328.

Murphy SK, Adigun A, Huang Z, Overcash F, Wang F, Jirtle RL et al. Gender-specific methylation differences in relation to prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke. Gene 2012; 494: 36–43.

Soubry A, Murphy SK, Huang Z, Murtha A, Schildkraut JM, Jirtle RL et al. The effects of depression and use of antidepressive medicines during pregnancy on the methylation status of the IGF2 imprinted control regions in the offspring. Clin Epigenetics 2011; 3: 2.

Vidal AC, Murphy SK, Murtha AP, Schildkraut JM, Soubry A, Huang Z et al. Associations between antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, birth weight and aberrant methylation at imprinted genes among offspring. Int J Obes 2013; 37: 907–913.

Cruz-Correa M, Zhao R, Oviedo M, Bernabe RD, Lacourt M, Cardona A et al. Temporal stability and age-related prevalence of loss of imprinting of the insulin-like growth factor-2 gene. Epigenetics 2009; 4: 114–118.

Barker DJ . Intrauterine programming of coronary heart disease and stroke. Acta Paediatr Suppl 1997; 423: 178–182 discussion 183.

Sun C, Burgner DP, Ponsonby AL, Saffery R, Huang RC, Vuillermin PJ et al. Effects of early-life environment and epigenetics on cardiovascular disease risk in children: highlighting the role of twin studies. Pediatr Res 2013; 73: 523–530.

Malaspina D . Paternal factors and schizophrenia risk: de novo mutations and imprinting. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27: 379–393.

Crespi B . Genomic imprinting in the development and evolution of psychotic spectrum conditions. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2008; 83: 441–493.

Murphy SK, Huang Z, Wen Y, Spillman MA, Whitaker RS, Simel LR et al. Frequent IGF2/H19 domain epigenetic alterations and elevated IGF2 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2006; 4: 283–292.

Steenman MJ, Rainier S, Dobry CJ, Grundy P, Horon IL, Feinberg AP . Loss of imprinting of IGF2 is linked to reduced expression and abnormal methylation of H19 in Wilms' tumour. Nat Genet 1994; 7: 433–439.

Sullivan MJ, Taniguchi T, Jhee A, Kerr N, Reeve AE . Relaxation of IGF2 imprinting in Wilms tumours associated with specific changes in IGF2 methylation. Oncogene 1999; 18: 7527–7534.

Cui H, Onyango P, Brandenburg S, Wu Y, Hsieh CL, Feinberg AP . Loss of imprinting in colorectal cancer linked to hypomethylation of H19 and IGF2. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 6442–6446.

Cruz-Correa M, Cui H, Giardiello FM, Powe NR, Hylind L, Robinson A et al. Loss of imprinting of insulin growth factor II gene: a potential heritable biomarker for colon neoplasia predisposition. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 964–970.

Basyuk E, Coulon V, Le Digarcher A, Coisy-Quivy M, Moles JP, Gandarillas A et al. The candidate tumor suppressor gene ZAC is involved in keratinocyte differentiation and its expression is lost in basal cell carcinomas. Mol Cancer Res 2005; 3: 483–492.

Bilanges B, Varrault A, Basyuk E, Rodriguez C, Mazumdar A, Pantaloni C et al. Loss of expression of the candidate tumor suppressor gene ZAC in breast cancer cell lines and primary tumors. Oncogene 1999; 18: 3979–3988.

Koy S, Hauses M, Appelt H, Friedrich K, Schackert HK, Eckelt U . Loss of expression of ZAC/LOT1 in squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck. Head Neck 2004; 26: 338–344.

Cvetkovic D, Pisarcik D, Lee C, Hamilton TC, Abdollahi A . Altered expression and loss of heterozygosity of the LOT1 gene in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 95: 449–455.

Lui JC, Finkielstain GP, Barnes KM, Baron J . An imprinted gene network that controls mammalian somatic growth is down-regulated during postnatal growth deceleration in multiple organs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 295: R189–R196.

Berg JS, Lin KK, Sonnet C, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Nguyen H et al. Imprinted genes that regulate early mammalian growth are coexpressed in somatic stem cells. PLoS One 2011; 6: e26410.

Varrault A, Gueydan C, Delalbre A, Bellmann A, Houssami S, Aknin C et al. Zac1 regulates an imprinted gene network critically involved in the control of embryonic growth. Dev Cell 2006; 11: 711–722.

Gabory A, Ripoche MA, Le Digarcher A, Watrin F, Ziyyat A, Forne T et al. H19 acts as a trans regulator of the imprinted gene network controlling growth in mice. Development 2009; 136: 3413–3421.

Lefebvre L, Viville S, Barton SC, Ishino F, Keverne EB, Surani MA . Abnormal maternal behaviour and growth retardation associated with loss of the imprinted gene Mest. Nat Genet 1998; 20: 163–169.

Benetatos L, Vartholomatos G, Hatzimichael E . MEG3 imprinted gene contribution in tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer 2011; 129: 773–779.

Perera F, Herbstman J . Prenatal environmental exposures, epigenetics, and disease. Reprod Toxicol 2011; 31: 363–373.

Figueroa-Colon R, Arani RB, Goran MI, Weinsier RL . Paternal body fat is a longitudinal predictor of changes in body fat in premenarcheal girls. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71: 829–834.

Kaati G, Bygren LO, Edvinsson S . Cardiovascular and diabetes mortality determined by nutrition during parents' and grandparents' slow growth period. Eur J Hum Genet 2002; 10: 682–688.

Loomba R, Hwang SJ, O'Donnell CJ, Ellison RC, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB Sr et al. Parental obesity and offspring serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels: the Framingham heart study. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 953–959.

Wu Q, Suzuki M . Parental obesity and overweight affect the body-fat accumulation in the offspring: the possible effect of a high-fat diet through epigenetic inheritance. Obes Rev 2006; 7: 201–208.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful toward the NEST families, voluntarily participating in this study. We acknowledge Francine Overcash and Stacy Murray for successfully coordinating the study and Rachel Maguire for the data management. We also thank the research nurse Tammy Bishop and technical assistance from Carole Grenier, Darby Kroyer, Erin Erginer, Cara Davis and Allison Barratt for processing the NEST specimens and generation of the methylation data. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (P30ES011961, R21ES014947, R01ES016772, R01DK085173 and R25CA126938), the American Cancer Society (ACS-IRG 83-006), and the Fred and Alice Stanback Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Soubry, A., Murphy, S., Wang, F. et al. Newborns of obese parents have altered DNA methylation patterns at imprinted genes. Int J Obes 39, 650–657 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.193

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.193

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Parental obesity predisposes to exacerbated metabolic and inflammatory disturbances in childhood obesity within the framework of an altered profile of trace elements

Nutrition & Diabetes (2024)

-

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Network Medicine Perspective

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2024)

-

Paternal nutrition: a neglected periconceptual influence on offspring health

Nutrire (2023)

-

Inheritance of paternal lifestyles and exposures through sperm DNA methylation

Nature Reviews Urology (2023)

-

Transcriptional vulnerabilities of striatal neurons in human and rodent models of Huntington’s disease

Nature Communications (2023)