Abstract

Objective:

A rat model of diet-induced obesity (DIO) was used to determine dopamine transporter (DAT) function, impulsivity and motivation as neurobehavioral outcomes and predictors of obesity.

Design:

To evaluate neurobehavioral alterations following the development of DIO induced by an 8-week high-fat diet (HF) exposure, striatal D2-receptor density, DAT function and expression, extracellular dopamine concentrations, impulsivity, and motivation for high- and low-fat reinforcers were determined. To determine predictors of DIO, neurobehavioral antecedents including impulsivity, motivation for high-fat reinforcers, DAT function and extracellular dopamine were evaluated before the 8-week HF exposure.

Methods:

Striatal D2-receptor density was determined by in vitro kinetic analysis of [3H]raclopride binding. DAT function was determined using in vitro kinetic analysis of [3H]dopamine uptake, methamphetamine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow and no-net flux in vivo microdialysis. DAT cell-surface expression was determined using biotinylation and western blotting. Impulsivity and food-motivated behavior were determined using a delay discounting task and progressive ratio schedule, respectively.

Results:

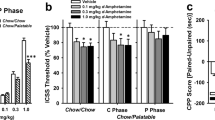

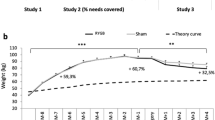

Relative to obesity-resistant (OR) rats, obesity-prone (OP) rats exhibited 18% greater body weight following an 8-week HF-diet exposure, 42% lower striatal D2-receptor density, 30% lower total DAT expression, 40% lower in vitro and in vivo DAT function, 45% greater extracellular dopamine and twofold greater methamphetamine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. OP rats exhibited higher motivation for food, and surprisingly, were less impulsive relative to OR rats. Impulsivity, in vivo DAT function and extracellular dopamine concentration did not predict DIO. Importantly, motivation for high-fat reinforcers predicted the development of DIO.

Conclusion:

Human studies are limited by their ability to determine if impulsivity, motivation and DAT function are causes or consequences of DIO. The current animal model shows that motivation for high-fat food, but not impulsive behavior, predicts the development of obesity, whereas decreases in striatal DAT function are exhibited only after the development of obesity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sclafani A . Psychobiology of food preferences. Int J Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders 2001; 25: S13–S16.

Gaillard D, Passilly-Degrace P, Besnard P . Molecular mechanisms of fat preference and overeating. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1141: 163–175.

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR . The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Indiv Differ 2001; 30: 669–689.

Weller RE, Cook EW, Avsar KB, Cox JE . Obese women show greater delay discounting than healthy-weight women. Appetite 2008; 51: 563–569.

Mobbs O, Crépin C, Thiéry C, Golay A, Van der Linden M . Obesity and the four facets of impulsivity. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 79: 372–377.

Appelhans BM, Woolf K, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Whited MC, Liebman R . Inhibiting food reward: delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011; 19: 2175–2182.

Martel P, Fantino M . Mesolimbic dopaminergic system activity as a function of food reward: a microdialysis study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1996; 53: 221–226.

Small DM, Jones-Gotman M, Dagher A . Feeding-induced dopamine release in dorsal striatum correlates with meal pleasantness ratings in healthy human volunteers. Neuroimage 2003; 19: 1709–1715.

Kelley AE . Ventral striatal control of appetitive motivation: role in ingestive behavior and reward-related learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2004; 27: 765–776.

Wise RA . Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci 2009; 32: 517–524.

Koob GF, Volkow ND . Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35: 217–238.

Szczypka MS, Kwok K, Brot MD, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Donahue BA et al. Dopamine production in the caudate putamen restores feeding in dopamine-deficient mice. Neuron 2001; 30: 819–828.

Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Tronson N, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR . Delta FosB in the nucleus accumbens regulates food-reinforced instrumental behavior and motivation. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 9196–9204.

Johnson PM, Kenny PJ . Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nat Neurosci 2010; 13: 635–641.

Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet 2001; 357: 354–357.

Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM . Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science 2008; 322: 449–452.

Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A . Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol 2005; 75: 406–433.

Peciña S, Cagniard B, Berridge KC, Aldridge JW, Zhuang X . Hyperdopaminergic mutant mice have higher ‘wanting’ but not ‘liking’ for sweet rewards. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 9395–9402.

Shinohara M, Mizushima H, Hirano M, Shioe K, Nakazawa M, Hiejima Y et al. Eating disorders with binge-eating behaviour are associated with the s allele of the 3′-UTR VNTR polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2004; 29: 134–137.

Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balkan B, Keesey RE . Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol 1997; 273: R725–R730.

Madsen AN, Hansen G, Paulsen SJ, Lykkegaard K, Tang-Christensen M, Hansen HS et al. Long-term characterization of the diet-induced obese and diet-resistant rat model: a polygenetic rat model mimicking the human obesity syndrome. J Endocrinol 2010; 206: 287–296.

Boustany CM, Bharadwaj K, Daugherty A, Brown DR, Randall DC, Cassis LA . Activation of the systemic and adipose renin-angiotensin system in rats with diet-induced obesity and hypertension. Am J Physiol 2004; 287: R943–R949.

Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Reed JA, Woods SC, Dunn-Meynell A, Levin BE . Reduced anorexic effects of insulin in obesity-prone rats fed a moderate-fat diet. Am J Physiol 2005; 288: R981–R986.

Dobrian AD, Davies MJ, Prewitt RL, Lauterio TJ . Development of hypertension in a rat model of diet-induced obesity. Hypertension 2000; 35: 1009–1015.

Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA . Reduced central leptin sensitivity in rats with diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol 2002; 283: R941–R948.

Sun W, Ginovart N, Ko F, Seeman P, Kapur S . In vivo evidence for dopamine-mediated internalization of D2-receptors after amphetamine: differential findings with [3H]raclopride versus [3H]spiperone. Mol Pharmacol 2003; 63: 456–462.

Nickell JR, Krishnamurthy S, Norrholm S, Deaciuc G, Siripurapu KB, Zheng G et al. Lobelane inhibits methamphetamine-evoked dopamine release via inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010; 332: 612–621.

Zhu J, Crooks PA, Ayers JT, Sumithran SP, Dwoskin LP N-n-Alkylnicotinium . and N-n-alkylpyridinium analogs inhibit of dopamine transporter function: selectivity as nicotinic receptor antagonists. Drug Dev Res 2003; 60: 270–284.

Miller DK, Crooks PA, Teng L, Witkin JM, Munzar P, Goldberg SR et al. Lobeline inhibits the neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001; 296: 1023–1034.

Zhu J, Apparsundaram S, Bardo MT, Dwoskin LP . Environmental enrichment decreases cell surface expression of the dopamine transporter in rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Neuroschem 2005; 93: 1434–1443.

Acri JB, Thompson AC, Shippenberg T . Modulation of pre- and postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptor function by the selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist U69593. Synapse 2001; 39: 343–350.

Marusich JA, Bardo MT . Differences in impulsivity on a delay-discounting task predict self-administration of a low unit dose of methylphenidate in rats. Behav Pharmacol 2009; 20: 447–454.

Richardson NR, Roberts DC . Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 1996; 66: 1–11.

Kern DL, McPhee L, Fisher J, Johnson S, Birch LL . The postingestive consequences of fat condition preferences for flavors associated with high dietary fat. Physiol Behav 1993; 54: 71–76.

Warwick ZS, Weingarten HP . Determinants of high-fat diet hyperphagia: experimental dissection of orosensory and postingestive effects. Am J Physiol 1995; 269: R30–R37.

Blum K, Chen TJ, Meshkin B, Downs BW, Gordon CA, Blum S et al. Reward deficiency syndrome in obesity: a preliminary cross-sectional trial with a genotrim variant. Adv Ther 2006; 23: 1040–1051.

Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschöp MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ et al. Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci 2008; 112: 1257–1263.

Geiger BM, Behr GG, Frank LE, Caldera-Siu AD, Beinfeld MC, Kokkotou EG et al. Evidence for defective mesolimbic dopamine exocytosis in obesity-prone rats. FASEB J 2008; 22: 2740–2746.

Ito R, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ . Dopamine release in the dorsal striatum during cocaine-seeking behavioral under the control of a drug-associated cue. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 6247–6253.

Everitt BJ, Robbins TW . Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8: 1481–1489.

Zahniser NR, Sorkin A . Rapid regulation of the dopamine transporter: role in stimulant addiction? Neuropharmacology 2004; 47: 80–91.

Cass WA, Gerhardt GA . Direct in vivo evidence that D2 dopamine receptors can modulate dopamine uptake. Neurosci Lett 1994; 176: 259–263.

Zhu SJ, Kavanaugh MP, Sonders MS, Amara SG, Zahniser NR . Activation of protein kinase C inhibits uptake, currents and binding associated with the human dopamine transporter expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 282: 1358–1365.

Kantor L, Gnegy ME . Protein kinase C inhibitors block amphetamine mediated dopamine release in rat striatal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998; 284: 594–598.

Khoshbouei H, Sen N, Guptaroy B, Johnson L, Lund D, Gnegy ME et al. N-terminal phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter is required for amphetamine-induced efflux. PLoS Biol 2004; 2: 387–393.

Robertson SD, Matthies HJ, Galli A . A closer look at amphetamine-induced reverse transport and trafficking of the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. Mol Neurobiol 2009; 39: 73–80.

Foster JD, Adkins SD, Lever JR, Vaughan RA . Phorbol ester induced trafficking-independent regulation and enhanced phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter associated with membrane rafts and cholesterol. J Neurochem 2008; 105: 1683–1699.

South T, Huang XF . High-fat diet exposure increases dopamine D2 receptor and decreases dopamine transporter receptor binding density in the nucleus accumbens and caudate putamen of mice. Neurochem Res 2008; 33: 598–605.

Kenny PJ . Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011; 12: 638–651.

Ersche KD, Turton AJ, Pradhan S, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW . Drug addiction endophenotypes: impulsive versus sensation-seeking personality traits. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 770–773.

Belin D, Berson N, Balado E, Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonet V . High-novelty-preference rats are predisposed to compulsive cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36: 569–579.

Thanos PK, Cho J, Kim R, Michaelides M, Primeaux S, Bray G et al. Bromocriptine increased operant responding for high fat food but decreased chow intake in both obesity-prone and resistant rats. Behav Brain Res 2011; 217: 165–170.

Glass MJ, O’Hare E, Cleary JP, Billington CJ, Levine AS . The effect of naloxone on food-motivated behavior in the obese Zucker rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 141: 378–384.

Hajnal A, Acharya NK, Grigson PS, Covasa M, Twining RC, Obese OLETF . rats exhibit increased operant performance for palatable sucrose solutions and differential sensitivity to D2 receptor antagonism. Am J Physiol 2007; 2293: R1846–R1854.

Fleur SE, Vanderschuren LJ, Luijendijk MC, Kloeze BM, Tiesjema B, Adan RA . A reciprocal interaction between food-motivated behavior and diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes 2007; 31: 1286–1294.

Okada S, York DA, Bray GA, Mei J, Erlanson-Albertsson C . Differential inhibition of fat intake in two strains of rat by the peptide enterostatin. Am J Physiol 1992; 262 (6 Part 2): R1111–R1116.

Rada P, Bocarsly ME, Barson JR, Hoebel BG, Leibowitz SF . Reduced accumbens dopamine in Sprague-Dawley rats prone to overeating a fat-rich diet. Physiol Behav 2010; 101: 394–400.

Krügel U, Schraft T, Kittner H, Kiess W, Illes P . Basal and feeding-evoked dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens is depressed by leptin. Eur J Pharmacol 2003; 482: 185–187.

Hommel JD, Trinko R, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Liu ZW, Gao XB et al. Leptin receptor signaling in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates feeding. Neuron 2006; 51: 801–810.

Figlewicz DP, Szot P, Chavez M, Woods SC, Veith RC . Intraventricular insulin increases dopamine transporter mRNA in rat VTA/substantia nigra. Brain Res 1994; 644: 331–334.

Figlewicz DP, Bennett J, Evans SB, Kaiyala K, Sipols AJ, Benoit SC . Intraventricular insulin and leptin reverse place preference conditioned with high-fat diet in rats. Behav Neurosci 2004; 118: 479–487.

Figlewicz DP, Bennett JL, Naleid AM, Davis C, Grimm JW . Intraventricular insulin and leptin decrease sucrose self-administration in rats. Physiol Behav 2006; 89: 611–616.

Davis JF, Choi DL, Schurdak JD, Fitzgerald MF, Clegg DJ, Lipton JW et al. Leptin regulates energy balance and motivation through action at distinct neural circuits. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 69: 668–674.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Agripina Deaciuc, Andrew Smith, Andrew Chip Meyer, David Lee, Deann Hopkins, Emily Denehy, Gurpreet Dhawan, Kate Fischer, Kiran Babu Siripurapu, Travis McCuddy and Victoria English for help with the assays. We thank Dr Robert Lorch for help with the statistical analyses. This research was supported by NIH P50 DA05312 (Linda P Dwoskin), NIH HL73085 and P20RR021954 (Lisa A Cassis) and a Pre-doctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association, AHA 715489B (Vidya Narayanaswami).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Narayanaswami, V., Thompson, A., Cassis, L. et al. Diet-induced obesity: dopamine transporter function, impulsivity and motivation. Int J Obes 37, 1095–1103 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.178

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.178

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A limited and intermittent access to a high-fat diet modulates the effects of cocaine-induced reinstatement in the conditioned place preference in male and female mice

Psychopharmacology (2021)

-

A Review of Childhood Behavioral Problems and Disorders in the Development of Obesity: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Beyond

Current Obesity Reports (2018)

-

Changes in gene expression and sensitivity of cocaine reward produced by a continuous fat diet

Psychopharmacology (2017)

-

Perturbed Development of Striatal Dopamine Transporters in Fatty Versus Lean Zucker Rats: a Follow-up Small Animal PET Study

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2015)