Abstract

Systolic hypertension, the predominant form of hypertension in patients aged over 50–60 years, is a growing health issue as the Asian population ages. Elevated systolic blood pressure is mainly caused by arterial stiffening, resulting from age-related vascular changes. Elevated systolic pressure increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, mortality and renal function decline, and this risk may increase at lower systolic pressure levels in Asian than Western subjects. Hence, effective systolic pressure lowering is particularly important in Asians yet blood pressure control remains inadequate despite the availability of numerous antihypertensive medications. Reasons for poor blood pressure control include low awareness of hypertension among health-care professionals and patients, under-treatment, and tolerability problems with antihypertensive drugs. Current antihypertensive treatments also lack effects on the underlying vascular pathology of systolic hypertension, so novel drugs that address the pathophysiology of arterial stiffening are needed for optimal management of systolic hypertension and its cardiovascular complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is a global public health issue and a major cause of morbidity and mortality, reported to be responsible for almost 13% of all deaths and 3.7% of total disability-adjusted life-years.1 The worldwide prevalence of hypertension in individuals aged ⩾25 years was estimated to be approximately 40% in 2008.1 This is equivalent to almost one billion people, and is predicted to increase to over 1.5 billion people by 2025.1, 2 The prevalence of hypertension is similarly high across different Asian countries, ranging from 30% in the Republic of Korea to 47% in Mongolia.3 Prevalence also increases with advancing age.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 For example, the prevalence in Chinese patients is 39% overall,3 59.4% in patients aged ⩾60 years4 and 72.8% in those aged ⩾75 years.6 With a rapidly aging population, the prevalence of hypertension and related cardiovascular morbidity in Asian patients continues to rise, placing a substantial and escalating social and economic burden on this region.8, 9, 10

The risk of cardiovascular disease (for example, stroke and peripheral arterial disease) in the Asian population is significantly increased with uncontrolled blood pressure (BP) and differs from that seen in patients from Western regions.11, 12, 13, 14 In an analysis of data from the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration, Asian patients with hypertension had a 4.5-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease vs. those with normal BP.15 Furthermore, the relationship between overall cardiovascular risk and hypertension was shown to be significantly stronger for Asian patients compared with participants from Australia and New Zealand (hazard ratios: 4.5 vs. 2.1; P<0.001).15 Elevated systolic BP (SBP) in particular is a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease in both Asian and Western populations.16, 17 Data from the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration have shown that the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke increases linearly as levels of SBP increase.18 In particular, the linear relationship between SBP and stroke risk is markedly more pronounced in Asian patients than in Caucasian populations (Figure 1).18 This may be attributable to the higher proportion of hemorrhagic vs. ischemic strokes reported in the Asian population, as hemorrhagic strokes correlate more closely with BP than do ischemic strokes. Overall, stroke is generally more common than CHD in Asians, whereas the converse is seen in Western subjects.19, 20 Evidence suggests that in addition to the risks posed by elevated SBP, visit-to-visit variability in SBP may also represent a predictor of cardiovascular disease, including stroke.21, 22

The higher risk of (a) fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease and (b) stroke, associated with higher systolic blood pressure levels by age and region in the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. SBP, systolic blood pressure. Reprinted with permission from Perkovic et al.18

Here we review the increasing burden of hypertension, focusing on systolic hypertension, the key risk factors for its development and the impact that raised SBP has on cardiovascular disease in Asian patients. We also discuss the challenges of managing hypertension and the current status of BP control, highlighting the unmet clinical needs that are apparent in Asian regions.

Epidemiology of systolic hypertension in Asian populations

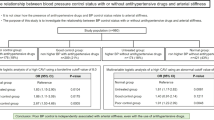

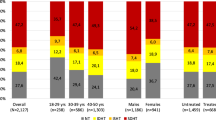

Hypertension is generally defined as SBP of ⩾140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) of ⩾90 mm Hg. Systolic hypertension can occur with DBP ⩾90 mm Hg (systolic/diastolic hypertension) or with normal DBP (isolated systolic hypertension), and is the predominant form of hypertension in patients ⩾60 years old.17 SBP increases after the age of 50–60 years, whereas DBP tends to decrease because of age-related changes in arterial vasculature, leading to a widening of pulse pressure (the difference between SBP and DBP). This suggests that SBP is the more important of the two BP components in the aging population.17, 23, 24 A meta-analysis of 41 cohort studies conducted by the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration clearly illustrated the progressive increase in SBP with advancing age in Asian patients (Figure 2).25 This has been corroborated by numerous other studies conducted across the region.26, 27, 28 Furthermore, a decrease in the prevalence of diastolic hypertension with age (presumably reflecting age-related changes in DBP) has also been reported in clinical studies in Asians (Figure 3).28, 29

Systolic blood pressure increases with age in Asian patients. ANZ, Australia and New Zealand; SBP, systolic blood pressure. Reprinted with permission from Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration.25

Diastolic hypertension becomes less prevalent with increasing patient age. IDH, isolated diastolic hypertension; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; SDH, systolic-diastolic hypertension. Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers: Journal of Human Hypertension.28

As would be expected, the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension in Asians, which is reported to be 3.9–12.5%, is age dependent.27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Several studies in Asian populations have reported that the increase in prevalence is particularly noticeable in subjects aged at least 60–65 years compared with younger individuals.28, 29, 30

The increasing proportion of older patients across Asia means that the burden of systolic hypertension is growing.9, 10, 26, 32 It is also anticipated that this increase will be more pronounced than in the rest of the world, primarily as a result of lifestyle changes such as consuming Western-style diets and undertaking less physical activity.9, 10 Hence, reducing SBP should be a primary goal for preventing cardiovascular disease in Asia, particularly in older patients with hypertension.

Pathophysiology of systolic hypertension

The primary underlying cause of age-related increases in SBP is arterial stiffening.33 Arterial stiffening results from a range of structural and functional changes to the aging vasculature, including arterial wall thickening, smooth muscle cell hypertrophy, inflammation, nitric oxide deficiency, fragmentation of elastin and increased dilatation. These changes occur mainly as a consequence of volume expansion, activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system, and endothelial dysfunction.23, 34 Deficiency of the natriuretic peptide system is also a key component in the development of hypertension,34 as natriuretic peptides inhibit the activity of both the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system and have a range of physiological effects including natriuresis and diuresis, vasodilatation, antiproliferation, antihypertrophy, antifibrosis, vascular regeneration and attenuation of cardiovascular remodeling.35, 36, 37 Arterial stiffening is recognized to be a precursor of the development of systolic hypertension, whereas hypertension itself can contribute to endothelial dysfunction.38 Reduced arterial compliance can also result from factors that damage the endothelium such as high dietary salt intake, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus and estrogen deficiency.

The loss of arterial elasticity increases pulse wave velocity so that the forward pressure wave that travels from the heart to the periphery is reflected back early toward the heart, returning in late systole rather than early diastole.39 This leads to increased SBP, reduced DBP and widened pulse pressure. The increased aortic stiffness and decreased aortic compliance in patients with hypertension have been shown to increase with duration of hypertension.40

Arterial stiffness is well established as a predictor of stroke, cardiovascular disease and decline in renal function in patients with hypertension.33 This relationship has been confirmed in Asian populations.41, 42, 43 In Asian patients with hypertension, increasing arterial stiffness was significantly associated with stroke41, 43 and cardiovascular disease,43 and predicted 15-year cardiovascular mortality.42 Other studies conducted in Asian regions have shown that arterial stiffening predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in elderly subjects,44 patients with end-stage renal disease45 and patients with acute coronary syndrome.46 In a Japanese study, arterial stiffness was significantly and independently associated with renal function decline.47

Key risk factors of systolic hypertension in Asian patients

High dietary salt

Asians generally have a higher salt intake than Westerners.48, 49 Excessive salt intake is associated with significantly increased SBP50, 51, 52 and BP-dependent progression of cardiovascular disease and stroke.49, 53, 54, 55, 56 In an early Taiwanese study, salt intake and hypertension were found to be independent risk factors for stroke.54 Similarly, a large prospective Japanese study showed that a 100-mmol increase in daily sodium intake increased death from stroke by 83%.56

Salt intake is more closely correlated with central hemodynamics than peripheral hemodynamics of the brachial artery in patients with hypertension.57, 58 Salt intake predominantly influences central BP, which is implicated in the development of arterial stiffening and directly affects stroke and renal disease. It is noteworthy, therefore, that measuring brachial BP is likely to underestimate the detrimental effects of salt intake on central BP.58 High salt intake may also increase the risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease independently of the effects of elevated BP,55 a hypothesis that has been supported by research demonstrating that dietary sodium alters vascular endothelial function independently of SBP changes.59

Reducing dietary sodium effectively reduces SBP in Asian patients.60, 61 Substitution of normal salt with reduced sodium, high-potassium salt has been shown to significantly reduce SBP in Chinese patients with hypertension.60 Even modest reductions in dietary sodium result in clinically significant reductions in SBP, as well as improving renal function and arterial stiffness.61 Reducing dietary sodium may be particularly effective in reducing SBP in older patients.62 Hence, salt reduction strategies may help to alleviate the burden of hypertension, and reduce the associated cardiovascular complications.

Obesity and overweight

The prevalence of systolic hypertension or raised SBP increases with increasing body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference in Asian subjects.28, 30, 63, 64, 65 In a large Indian study, the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension increased from 2.8% among patients with a BMI <18.5 kg m–2 to 21.1% in those with a BMI ⩾30 kg m–2.30 Abdominal obesity assessed by waist circumference was shown to be particularly important for predicting systolic hypertension in large studies of Chinese and Korean women,63, 64 whereas BMI (denoting general obesity) appears to have a more important influence on uncontrolled hypertension in men.64 Being overweight or obese also predicts increased SBP and incident hypertension in patients with prehypertension.52 Indeed, a linear relationship between BMI and risk of prehypertension was demonstrated in a cross-sectional Japanese study.65

The impact of obesity on hypertension appears to be elevated in Asian subjects compared with Western subjects;11 a BMI of 25 kg m–2 in Asians has a similar impact on prehypertension and hypertension as a BMI of 30 kg m–2 in Western individuals.66, 67 Obesity and associated metabolic syndrome are becoming more common in Asian regions.68 Both of these conditions increase salt sensitivity.69, 70 Hence, Asians with high salt intake or salt sensitivity may experience increases in BP if they are overweight or only mildly obese.

Consequences of elevated SBP

Data from the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration found that raised SBP is a key risk factor for CHD, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic heart disease, and cardiovascular and renal deaths.15, 16, 25, 71, 72, 73 Total risk of cardiovascular disease was increased 4.5-fold in Asian patients with systolic–diastolic hypertension and 2.7-fold in those with isolated systolic hypertension compared with normotensive individuals.15 Moreover, for every additional 10 mm Hg elevation in SBP the risk of CHD increases by 23%, ischemic stroke by 43% and hemorrhagic stroke by 74%.16 Figure 4 shows the linear association between usual SBP and hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke and other strokes in the Asia-Pacific region.74 A similar linear relationship between increasing levels of SBP and stroke risk was demonstrated in a Japanese study.75 In Asian patients from the Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration, SBP >140 mm Hg was significantly and independently associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage, a subtype of stroke that is associated with high morbidity and mortality.76 Two large population-based cohort studies reported that SBP is a stronger independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and stroke compared with DBP.75, 77 SBP is also the strongest risk factor for renal death, with each 19 mm Hg increase correlating to a >80% higher risk.78

There is a linear association between usual SBP and ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke and other strokes in the Asia-Pacific region. SBP, systolic blood pressure. Adapted with permission from Lippincott Williams and Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer Health: Stroke.74

The impact of raised SBP on cardiovascular risk has been shown to vary with different patient characteristics. First, the effect of elevated SBP on cardiovascular disease increases substantially with age (Figure 1).18, 25 In Japanese patients aged ⩾75 years with high-risk hypertension, cardiovascular risk significantly increased when SBP was ⩾150 mm Hg.79 In very elderly patients (aged ⩾80 years) with cardiovascular disease (for example, angina or stroke) and taking antihypertensive medications, elevated SBP was significantly associated with total mortality.80 Second, there appears to be a gender difference in the impact of elevated SBP on cardiovascular and renal risk. A 10 mm Hg increase in SBP was found to be associated with a 15% higher risk of CHD mortality in women than in men.81 The opposite was true for the association between SBP and renal death.78 Third, cardiovascular risk may increase at lower thresholds for SBP and DBP in Asian compared with Western populations. For example, in a large cohort study in India, SBP ⩾120 mm Hg and DBP ⩾90 mm Hg were significantly associated with a greater risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke.77 The associations between SBP and cardiovascular risk were also stronger in Asians compared with subjects from Australia and New Zealand in an Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration analysis.15

Management of systolic hypertension

Asian evidence on clinical outcome benefits of SBP control with antihypertensive drugs

A number of clinical trials conducted in Asian patients have demonstrated that lowering SBP is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk. The Systolic Hypertension in China trial investigated the effects of antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular risk in 2394 Chinese patients aged at least 60 years.82 After a median follow-up of 3 years, step-wise active treatment with a calcium channel blocker (CCB) with or without an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) and/or a thiazide diuretic significantly reduced the rate of fatal and nonfatal strokes by 38%, stroke mortality by 58%, fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events by 37%, cardiovascular mortality by 39% and total mortality by 39% (Figure 5). Additional analyses found that these beneficial effects were generally similar regardless of patients’ characteristics such as gender, age, previous cardiovascular complications or geographical location.83 Another study from China showed that a reduction in SBP/DBP (4.2/2.1 mm Hg) achieved by adding a CCB to thiazide diuretic-based therapy was accompanied by significantly greater reductions in fatal and nonfatal stroke (27%), cardiovascular events (27%), cardiac events (35%) and cardiovascular deaths (33%) compared with diuretic-based therapy.84 The Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study reported that BP-lowering effects of ACEI-based treatment resulted in fewer stokes and major cardiovascular events in Asian patients.85

A number of studies have suggested that reduction in cardiovascular events may be achieved irrespective of the class of antihypertensive agent used. In the Japanese Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events trial, the impact of combination therapy with a CCB plus one additional antihypertensive agent (angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blocker or thiazide diuretic) on cardiovascular events and BP control was assessed in 3501 patients with hypertension aged 40–85 years.86 After a median follow-up of 3.6 years, all three CCB-based regimens reduced average BP to a similar extent and there were no differences in the composite primary end point (reduction in risk of cardiovascular events and achievement of target BP). ARB- or CCB-based treatment regimens were shown to confer comparable cardiovascular protective effects in the Candesartan Antihypertensive Survival Evaluation in Japan trial in 4728 high-risk patients with hypertension.79 Similarly, there were no differences in the incidence of cardiovascular events or mortality between CCB- and ACEI-based treatment in Japanese studies of patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease87 and elderly patients with hypertension.88

Other studies have investigated whether the target for SBP control influences the impact of treatment on cardiovascular events. The Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension trial was conducted in 3260 Japanese patients aged 70–84 years with isolated systolic hypertension to evaluate the impact of treatment with ARB-based therapy on cardiovascular events.89 Patients were randomized according to the target level of SBP control: strict (<140 mm Hg) or moderate (140–150 mm Hg). After a median of 3 years’ follow-up, SBP was reduced by 5.6 mm Hg in the strict vs. moderate control groups (P<0.001) but this was not accompanied by a significant decrease in the primary end point, a composite of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular disease and renal failure.90 The authors suggested that the lower than anticipated rates of the primary outcome were likely to have affected the power to detect between-group differences. Similar findings were reported in the Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients in which patients aged 65–85 years received CCB-based therapy.91 Strict SBP control (target of <140 mm Hg) achieved significantly lower BP compared with the mild control group (SBP target of 140–<160 mm Hg) but there was no difference in the combined incidence of cardiovascular disease and renal failure.

Guidelines on BP-lowering goals

There are no overall guidelines for the management of hypertension in Asia.92, 93 Therefore, local country guidelines or standard clinical practice guide the management of hypertension throughout Asia.92 The major features and themes of Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese hypertension guidelines are similar to European and US guidelines,92, 94, 95 but there are a number of subtle differences between the Asian guidelines. For example, 120–139/80–89 mm Hg range is termed ‘prehypertension’ in Korea and Taiwan, ‘normal high BP’ in China, and defines both ‘normal BP’ and ‘high-normal BP’ in Japan.9, 92, 96, 97, 98 The current Japanese hypertension guidelines recommend a BP target of <150/90 mm Hg for elderly patients aged ⩾75 years, whereas in the Chinese guidelines, the same BP target is recommended for elderly patients aged ⩾65 years.92, 98

Local guidelines give limited guidance specifically on the management of systolic hypertension, although some experts acknowledge its higher prevalence in the elderly population.98 Antihypertensive treatment is recommended in elderly patients but it is advised that BP reduction should be more gradual in this patient population.9, 96, 97, 98 The Japanese and Taiwanese guidelines recognize that lowering elevated SBP is important even in patients who have low DBP.9, 98 However, the Japanese guidelines recommend that in the presence of coronary artery disease, changes in DBP be monitored while lowering SBP to the target level.98

Awareness and implementation of local guidelines is generally inadequate in many Asian regions.10, 99, 100 Development of Asian hypertension guidelines based on evidence from studies conducted in patients in the region would help to provide practical guidance on how best to achieve BP goals. The guidelines could also be adapted and translated according to the local needs, which would help to provide clear terminology and defined treatment goals.

Current treatment options

The primary goal of antihypertensive treatment is to lower BP, thereby reducing cardiovascular complications.9, 97, 98 Non-pharmacological interventions for BP control recommended by Asian guidelines focus on lifestyle modifications, primarily reducing dietary sodium, weight loss, adopting a diet rich in fruit/vegetables and low-fat dairy products, physical activity, smoking cessation, and reducing alcohol intake.9, 96, 97, 98 However, few patients achieve BP goals through lifestyle modifications alone and antihypertensive drug therapy is generally required.

A large number of pharmacological treatments from different drug classes are recommended for the treatment of hypertension in Asia, for example, diuretics, β-blockers, ACEIs, ARBs, CCBs and direct vasodilators.9, 96, 97, 98 The most commonly used antihypertensive drugs in Asian countries are the CCBs,101 generally followed by ACEIs and ARBs,100, 102, 103 although β-blockers are also frequently prescribed in Taiwan.104 Patients receiving a CCB have been reported to achieve the highest rates of BP control,102 whereas ARBs and ACEIs may have tolerability and/or adherence advantages.103, 105 Use of ARBs has increased in recent years, possibly in response to the greater number of ARBs becoming available.103, 104 Low use of diuretics, despite cost advantages compared with other antihypertensive drug classes, may be related to the fact that diuretics in Asians are more likely to cause serious side effects, such as hypokalemia, because dietary potassium intake in Asians is low106 and to the perception that diuresis affects kidney function in traditional Chinese medicine, so these agents are not as suitable for hypertension.104 As in Western hypertensive patients, many Asian patients will require at least two antihypertensive medications to achieve their BP targets,9, 97, 98, 107 and use of single-pill combinations can improve the convenience and simplicity of the drug regimen.9, 98

Selecting appropriate medications for individuals’ needs is a particular challenge in Asian populations because of the lack of sufficient Asia-specific evidence for available therapies.10 However, Taiwanese guidelines specifically recommend treatment with a thiazide diuretic, CCB or ARB for isolated systolic hypertension.9 In elderly patients, who are most likely to have isolated systolic hypertension, Japanese guidelines recommend treatment with a CCB, ARB, ACEI or low-dose thiazide diuretic as first-line therapy.98 Korean guidelines highlight that CCBs and diuretics are effective first-line therapies for older patients.97 Specific drugs may also be required for patients with associated conditions such as heart failure, diabetes, chronic kidney disease or recurrent stroke.9, 97, 98

Limitations of contemporary drug therapy

Although existing antihypertensive drugs have demonstrated efficacy in lowering BP and reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in numerous clinical trials,108 hypertension remains an area of significant unmet medical needs. BP control is often suboptimal in clinical practice,10, 98 with rates among Asian patients with hypertension rarely exceeding 50% and reported to be <1% in certain communities.9, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114 In the 4th China National Nutrition and Health Survey in 2002, 82% of the Chinese hypertensive patients who were aware of the disease received antihypertensive treatment, yet the BP control rate was only 25% in this treated group, which in addition to the low awareness of hypertension (30%), was the major reason for the low control rate in all hypertensive patients (6%).115 Lack of SBP control is a particular problem, especially in older Asian patients.64, 116

Currently available antihypertensive agents are associated with numerous side effects, some of which are class dependent and/or potentially serious, including new-onset diabetes.117 Some side effects, such as ACEI-induced cough, may also be more pronounced in Asian patients.118 Concerns about side effects and a lack of confidence about the efficacy of ‘Western’ antihypertensive medications are common reasons for non-adherence among Asian patients, and are likely to affect BP control rates.10, 119

The BP-lowering efficacy of current antihypertensive agents is well established but their ability to lower SBP levels to <140 mm Hg is compromised by their lack of effect on age-related arterial stiffening.120 Moreover, the potential for improvement in vascular compliance with available ACEIs and ARBs may be hindered by the age-related decline in plasma renin activity.121 At present, there are no treatments that specifically target the reduction of arterial stiffening. As such, the development of novel drugs with direct effects on the underlying causes of arterial stiffness, such as renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and sympathetic nervous system activation alongside endothelial dysfunction and natriuretic peptide deficiency may be a key step toward optimizing the management of systolic hypertension and its complications.

Clinical challenges of hypertension in Asia

Lack of awareness

Awareness of hypertension is unacceptably low among Asian health-care professionals, patients and the public, and is one of the major contributors to the poor rates of BP control.10 Many studies in Asian communities have shown that 50–80% of people are unaware of the condition and/or that it is potentially fatal.109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 115, 116, 122 Poor patient knowledge about hypertension and the need for chronic therapy to achieve and maintain BP control often leads to lack of adherence, which therefore has a detrimental impact on BP-lowering strategies.123, 124

Under-treatment

Under-treatment of hypertension is a common problem in Asian countries, with rates of antihypertensive treatment for uncontrolled BP ranging widely from 2.6 to 65.8%.4, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113 In addition, physicians in Asian regions tend to prescribe lower doses of antihypertensive agents than recommended in Western countries because of concerns over tolerability, potentially leading to suboptimal dosing and insufficient titration for achieving BP goals;10 however, evidence suggests that upward dose titration of antihypertensive agents in Asian patients with hypertension can provide incremental BP-lowering efficacy without, in comparison with Western subjects, significantly affecting its tolerability profile.125

Physicians may also be concerned about the potentially harmful effects of excessive reduction in DBP when trying to attain SBP goals with antihypertensive drugs in older patients with hypertension.120, 126 Traditionally, guidelines emphasized the control of DBP as the most important factor when treating hypertension, and an increase in SBP was seen as a normal and inconsequential part of the aging process.120 Therefore, poor understanding of the importance of SBP control among some physicians may limit the effectiveness of hypertension management.

Diversity across Asia

Asia is a region of extensive social, economic, geographic and political diversity.127 Consequently, the health status of populations across Asia varies markedly. For example, a strong inverse association between disease prevalence and national wealth typifies how economic diversity between countries can influence the impact of disease burden.127 Across Asia, the demand for better quality health care is increasing. Yet as national health systems across Asia are evolving at contrasting rates,127 it is likely that not all countries would be able to meet such demand in their current form. Indeed, the quality and provision of management strategies for systolic hypertension currently used across the region are likely to vary considerably, with developed countries more likely to facilitate optimal patient care than those less developed countries. Therefore, the enormous diversity evident in Asia today represents a significant hurdle to achieving uniform BP control across the region. Nevertheless, with most countries across Asia looking to fully embrace economic and social development in the coming years, existing gaps in health-care provision are expected to diminish, facilitating the improved management of hypertension throughout the majority of the region.

Lack of therapeutic agents targeting arterial stiffening

Lifestyle and risk management advice from health-care professionals can help to lower BP in patients with hypertension and prevent the development of hypertension in patients identified to be at risk.128, 129 However, uncontrolled hypertension remains a significant problem even when such interventions are implemented.129 Improving the awareness of hypertension and ensuring patients are treated appropriately would undoubtedly improve BP control rates.10 Nonetheless, many patients remain uncontrolled even when currently available therapies are prescribed.120 Lack of BP control is primarily because of insufficient reduction in SBP, particularly in aging populations,130 which is a consequence of age-related vascular stiffening.131 Clinical evidence has indicated that survival of patients with end-stage renal failure is improved by reductions in arterial stiffness (assessed by aortic pulse wave velocity) in response to BP lowering—patients without reductions in arterial stiffness in response to BP changes had an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.132 However, age-related vascular changes are difficult to reverse with available antihypertensive medications.

Therefore, focusing on lowering SBP rather than DBP by reducing arterial stiffness may be an important therapeutic target for the future management of hypertension.38 A number of new therapies targeting vascular pathophysiology, which may lower SBP, are currently in clinical development.133, 134, 135, 136 These include a first-in-class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (LCZ696), a dual-specificity AT1R and endothelin A receptor antagonist (PS433540), an aldosterone synthase inhibitor (LCI699), a natriuretic peptide receptor antagonist (PL3994) and a soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor (AR9281).135, 136

Summary

Hypertension remains a significant clinical problem in both Asia and the rest of the world. Systolic hypertension is the predominant form of hypertension in older patients and therefore represents a major and growing health burden in the aging population. The increase in the prevalence of elevated SBP is likely to be more pronounced in Asian than Western populations because of the adoption of detrimental lifestyle changes in Asian individuals and other factors, such as excessive salt intake and increased sensitivity to weight gain. As elevated SBP is a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality, reducing SBP should be a primary goal in the management of hypertension, particularly as patients are aging.

Despite the availability of numerous antihypertensive medications, BP control rates are unacceptably low in Asian regions. Increasing awareness and knowledge of hypertension among both health-care professionals and patients may help reduce the escalating social and economic burden of this disease. However, one of the key problems with currently available antihypertensive therapies is their lack of effect on the main determinant of SBP, namely arterial stiffness. Hence, new therapeutic options that target the underlying vascular pathophysiology of elevated SBP are needed to reduce the burden and consequences of systolic hypertension. In addition, research should be conducted to determine the roles of such new therapies specifically in the management of Asian patients with systolic hypertension.

References

WHO Global Health Observatory. Prevalence of raised blood pressure: situations and trends. http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/blood_pressure_prevalence_text/en/ (accessed 10 June 2014).

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J . Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens 2004; 22: 11–19.

World Health Organization Prevalence of raised blood pressure, ages 25+, 2008. http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/ncd/risk_factors/blood_pressure_prevalence/atlas.html (accessed 10 June 2014).

Sheng CS, Liu M, Kang YY, Wei FF, Zhang L, Li GL, Dong Q, Huang QF, Li Y, Wang JG . Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in elderly Chinese. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 824–828.

Davarian S, Crimmins E, Takahashi A, Saito Y . Sociodemographic correlates of four indices of blood pressure and hypertension among older persons in Japan. Gerontology 2013; 59: 392–400.

Li YC, Wang LM, Jiang Y, Li XY, Zhang M, Hu N . Prevalence of hypertension among Chinese adults in 2010. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012; 46: 409–413 [in Chinese].

Gupta R, Sharma KK, Gupta A, Agrawal A, Mohan I, Gupta VP, Khedar RS, Guptha S . Persistent high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the urban middle class in India: Jaipur Heart Watch-5. J Assoc Physicians India 2012; 60: 11–16.

Lee JH, Yang DH, Park HS, Cho Y, Jun JE, Park WH, Chun BY, Shin JY, Shin DH, Lee KS, Kim KS, Kim KB, Kim YJ, Chae SC . Incidence of hypertension in Korea: 5-year follow-up study. J Korean Med Sci 2011; 26: 1286–1292.

Chiang CE, Wang TD, Li YH, Lin TH, Chien KL, Yeh HI, Shyu KG, Tsai WC, Chao TH, Hwang JJ, Chiang FT, Chen JH . 2010 guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology for the management of hypertension. J Formos Med Assoc 2010; 109: 740–773.

Chung N, Baek S, Chen MF, Liau CS, Park CG, Park J, Saruta T, Shimamoto K, Wu Z, Zhu J, Fujita T . Expert recommendations on the challenges of hypertension in Asia. Int J Clin Pract 2008; 62: 1306–1312.

Kario K . Proposal of a new strategy for ambulatory blood pressure profile-based management of resistant hypertension in the era of renal denervation. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 564.

Kang DG, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, Chae SC, Hur SH, Hong TJ, Kim YJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Rhew JY, Chae IH, Cho MC, Bae JH, Rha SW, Kim CJ, Jang YS, Yoon J, Seung KB, Park SJ . Clinical effects of hypertension on the mortality of patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Korean Med Sci 2009; 24: 800–806.

Shimamoto K, Fujita T, Ito S, Naritomi H, Ogihara T, Shimada K, Tanaka H, Yoshiike N . Impact of blood pressure control on cardiovascular events in 26,512 Japanese hypertensive patients: the Japan Hypertension Evaluation with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan Therapy (J-HEALTH) study, a prospective nationwide observational study. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 469–478.

Yang X, Sun K, Zhang W, Wu H, Zhang H, Hui R . Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the patients with hypertension among Han Chinese. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 296–302.

Arima H, Murakami Y, Lam TH, Kim HC, Ueshima H, Woo J, Suh I, Fang X, Woodward M . Effects of prehypertension and hypertension subtype on cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific Region. Hypertension 2012; 59: 1118–1123.

Kengne AP, Patel A, Barzi F, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Ueshima H, Gu DF, Suh I, Woodward M . Systolic blood pressure, diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1205–1213.

Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, L'Italien GJ, Lapuerta P . Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension 2001; 37: 869–874.

Perkovic V, Huxley R, Wu Y, Prabhakaran D, MacMahon S . The burden of blood pressure-related disease: a neglected priority for global health. Hypertension 2007; 50: 991–997.

Ueshima H . Explanation for the Japanese paradox: prevention of increase in coronary heart disease and reduction in stroke. J Atheroscler Thromb 2007; 14: 278–286.

Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, Kajii E, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Kario K . Prehypertension and the risk for cardiovascular disease in the Japanese general population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 1630–1637.

Okada H, Fukui M, Tanaka M, Matsumoto S, Mineoka Y, Nakanishi N, Tomiyasu K, Nakano K, Hasegawa G, Nakamura N . Visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure is a novel risk factor for the progression of coronary artery calcification. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 996–999.

Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O'Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR . Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010; 375: 895–905.

Duprez DA . Systolic hypertension in the elderly: addressing an unmet need. Am J Med 2008; 121: 179–184.

Williams B, Lindholm LH, Sever P . Systolic pressure is all that matters. Lancet 2008; 371: 2219–2221.

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on the age-related excess risk of coronary heart disease. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 1025–1033.

He S, Chen XP, Chen XN, Li LX, Wan LY, Peng Y, Gong L, Cui CJ, Zhu Y, Huang DJ . Changes of prevalence of hypertension and blood pressure levels in 1061 adults in Chengdu from 1992 to 2007. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2010; 41: 494–497 535.

Li J, Xu C, Sun Z, Zheng L, Li J, Zhang D, Zhang X, Liu S, Zhao F, Hu D, Sun Y . Prevalence and risk factors for isolated untreated systolic hypertension in rural Mongolian and Han populations. Acta Cardiol 2008; 63: 389–393.

Kim JA, Kim SM, Choi YS, Yoon D, Lee JS, Park HS, Kim HA, Lee J, Oh HJ, Choi KM . The prevalence and risk factors associated with isolated untreated systolic hypertension in Korea: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. J Hum Hypertens 2007; 21: 107–113.

Kim BG, Park JT, Ahn Y, Kimm K, Shin C . Geographical difference in the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension in middle-aged men and women in Korea: the Korean Health and Genome Study. J Human Hypertens 2005; 19: 877–883.

Midha T, Idris MZ, Saran RK, Srivastava AK, Singh SK . Isolated systolic hypertension and its determinants – a cross-sectional study in the adult population of Lucknow District in North India. Indian J Community Med 2010; 35: 89–93.

Ruixing Y, Hui L, Jinzhen W, Weixiong L, Dezhai Y, Shangling P, Jiandong H, Xiuyan L . Association of diet and lifestyle with blood pressure in the Guangxi Hei Yi Zhuang and Han populations. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12: 553–561.

Wang J, Ning X, Yang L, Lu H, Tu J, Jin W, Zhang W, Su TC . Trends of hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in rural areas of northern China during 1991-2011. J Hum Hypertens 2014; 28: 25–31.

Park S, Lakatta EG . Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of arterial stiffness. Yonsei Med J 2012; 53: 258–261.

Oparil S, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA . Pathogenesis of hypertension. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 761–776.

Gardner DG, Chen S, Glenn DJ, Grigsby CL . Molecular biology of the natriuretic peptide system: implications for physiology and hypertension. Hypertension 2007; 49: 419–426.

Pandey KN . Emerging roles of natriuretic peptides and their receptors in pathophysiology of hypertension and cardiovascular regulation. J Am Soc Hypertens 2008; 2: 210–226.

Rubattu S, Sciarretta S, Valenti V, Stanzione R, Volpe M . Natriuretic peptides: an update on bioactivity, potential therapeutic use, and implication in cardiovascular diseases. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 733–741.

Kaess BM, Rong J, Larson MG, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF . Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA 2012; 308: 875–881.

Izzo JL Jr, Shykoff BE . Arterial stiffness: clinical relevance, measurement, and treatment. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2001; 2: 29–34 37–40.

Meenakshisundaram R, Kamaraj K, Murugan S, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P . Aortic stiffness and distensibility among hypertensives. Ann NY Acad Sci 2009; 1173: E68–E71.

Xu TY, Li Y, Wang YQ, Li YX, Zhang Y, Zhu DL, Gao PJ . Association of stroke with ambulatory arterial stiffness index (AASI) in hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens 2011; 33: 304–308.

Wang KL, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Chuang SY, Li CH, Spurgeon HA, Ting CT, Najjar SS, Lakatta EG, Yin FC, Chou P, Chen CH . Wave reflection and arterial stiffness in the prediction of 15-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities: a community-based study. Hypertension 2010; 55: 799–805.

Ohishi M, Tatara Y, Ito N, Takeya Y, Onishi M, Maekawa Y, Kato N, Kamide K, Rakugi H . The combination of chronic kidney disease and increased arterial stiffness is a predictor for stroke and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 2011; 34: 1209–1215.

Matsuoka O, Otsuka K, Murakami S, Hotta N, Yamanaka G, Kubo Y, Yamanaka T, Shinagawa M, Nunoda S, Nishimura Y, Shibata K, Saitoh H, Nishinaga M, Ishine M, Wada T, Okumiya K, Matsubayashi K, Yano S, Ichihara K, Cornelissen G, Halberg F, Ozawa T . Arterial stiffness independently predicts cardiovascular events in an elderly community — Longitudinal Investigation for the Longevity and Aging in Hokkaido County (LILAC) study. Biomed Pharmacother 2005; 59 (Suppl 1): S40–S44.

Shoji T, Emoto M, Shinohara K, Kakiya R, Tsujimoto Y, Kishimoto H, Ishimura E, Tabata T, Nishizawa Y . Diabetes mellitus, aortic stiffness, and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 2117–2124.

Tomiyama H, Koji Y, Yambe M, Shiina K, Motobe K, Yamada J, Shido N, Tanaka N, Chikamori T, Yamashina A . Brachial — ankle pulse wave velocity is a simple and independent predictor of prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circ J 2005; 69: 815–822.

Tomiyama H, Tanaka H, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto C, Odaira M, Yamada J, Yoshida M, Shiina K, Nagata M, Yamashina A . Arterial stiffness and declines in individuals with normal renal function/early chronic kidney disease. Atherosclerosis 2010; 212: 345–350.

Stamler J . The INTERSALT Study: background, methods, findings, and implications. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 65: 626S–642S.

Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP . Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009; 339: b4567.

Miura K, Okuda N, Turin TC, Takashima N, Nakagawa H, Nakamura K, Yoshita K, Okayama A, Ueshima H . Dietary salt intake and blood pressure in a representative Japanese population: baseline analyses of NIPPON DATA80. J Epidemiol 2010; 20 (Suppl 3): S524–S530.

Radhika G, Sathya RM, Sudha V, Ganesan A, Mohan V . Dietary salt intake and hypertension in an urban south Indian population—[CURES - 53]. J Assoc Physicians India 2007; 55: 405–411.

Zheng L, Sun Z, Zhang X, Xu C, Li J, Hu D, Sun Y . Predictors of progression from prehypertension to hypertension among rural Chinese adults: results from Liaoning Province. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010; 17: 217–222.

Kawano Y, Ando K, Matsuura H, Tsuchihashi T, Fujita T, Ueshima H . Report of the Working Group for Dietary Salt Reduction of the Japanese Society of Hypertension: (1) rationale for salt restriction and salt-restriction target level for the management of hypertension. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 879–886.

Hu HH, Sheng WY, Chu FL, Lan CF, Chiang BN . Incidence of stroke in Taiwan. Stroke 1992; 23: 1237–1241.

Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Shimizu N, Shimizu H . Sodium intake and risk of death from stroke in Japanese men and women. Stroke 2004; 35: 1543–1547.

Umesawa M, Iso H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Toyoshima H, Watanabe Y, Kikuchi S, Koizumi A, Kondo T, Inaba Y, Tanabe N, Tamakoshi A . Relations between dietary sodium and potassium intakes and mortality from cardiovascular disease: the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risks. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88: 195–202.

Park S, Park JB, Lakatta EG . Association of central hemodynamics with estimated 24-h urinary sodium in patients with hypertension. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 1502–1507.

Starmans-Kool MJ, Stanton AV, Xu YY, SAMcG Thom, Parker KH, Hughes AD . High dietary salt intake increases carotid blood pressure and wave reflection in normotensive healthy young men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011; 110: 468–471.

Jablonski KL, Racine ML, Geolfos CJ, Gates PE, Chonchol M, McQueen MB, Seals DR . Dietary sodium restriction reverses vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged/older adults with moderately elevated systolic blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 335–343.

Zhou B, Wang HL, Wang WL, Wu XM, Fu LY, Shi JP . Long-term effects of salt substitution on blood pressure in a rural north Chinese population. J Hum Hypertens 2013; 27: 427–433.

He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, Markandu ND, Anand V, Dalton RN, MacGregor GA . Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension 2009; 54: 482–488.

He J, Gu D, Chen J, Jaquish CE, Rao DC, Hixson JE, Chen JC, Duan X, Huang JF, Chen CS, Kelly TN, Bazzano LA, Whelton PK . Gender difference in blood pressure responses to dietary sodium intervention in the GenSalt study. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 48–54.

Zhang X, Yao S, Sun G, Yu S, Sun Z, Zheng L, Xu C, Li J, Sun Y . Total and abdominal obesity among rural Chinese women and the association with hypertension. Nutrition 2012; 28: 46–52.

Lee HS, Park YM, Kwon HS, Lee JH, Yoon KH, Son HY, Kim DS, Yim HW, Lee WC . Factors associated with control of blood pressure among elderly people diagnosed with hypertension in a rural area of South Korea: the Chungju Metabolic Disease Cohort Study (CMC study). Blood Press 2010; 19: 31–39.

Kawamoto R, Kohara K, Tabara Y, Miki T . High prevalence of prehypertension is associated with the increased body mass index in community-dwelling Japanese. Tohoku J Exp Med 2008; 216: 353–361.

Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, Kayaba K, Nakamura Y, Shimada K, Kajii E, Pickering TG, Kario K . Prevalence and determinants of prehypertension in a Japanese general population: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 1323–1330.

Greenlund KJ, Croft JB, Mensah GA . Prevalence of heart disease and stroke risk factors in persons with prehypertension in the United States, 1999–2000. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 2113–2118.

Kubo M, Hata J, Doi Y, Tanizaki Y, Lida M, Kiyohara Y . Secular trends in the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke and its subtypes in Japanese population. Circulation 2008; 118: 2672–2678.

Uzu T, Kimura G, Yamauchi A, Kanasaki M, Isshiki K, Araki S, Sugiomoto T, Nishio Y, Maegawa H, Koya D, Haneda M, Kashiwagi A . Enhanced sodium sensitivity and disturbed circadian rhythm of blood pressure in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 1627–1632.

Chen J, Gu D, Huang J, Rao DC, Jaquish CE, Hixson JE, Chen CS, Chen J, Lu F, Hu D, Rice T, Kelly TN, Hamm LL, Whelton PK, He J . Metabolic syndrome and salt sensitivity of blood pressure in non-diabetic people in China: a dietary intervention study. Lancet 2009; 373: 829–835.

Woodward M, Tsukinoki-Murakami R, Murakami Y, Suh I, Fang X, Ueshima H, Lam TH . The epidemiology of stroke amongst women in the Asia-Pacific region. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2011; 7: 305–317.

Woodward M, Huxley H, Lam TH, Barzi F, Lawes CM, Ueshima H Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration.. A comparison of the associations between risk factors and cardiovascular disease in Asia and Australasia. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005; 12: 484–491.

Lawes CM, Rodgers A, Bennett DA, Parag V, Suh I, Ueshima H, MacMahon S . Blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 707–716.

Nakamura K, Barzi F, Lam TH, Huxley R, Feigin VL, Ueshima H, Woo J, Gu D, Ohkubo T, Lawes CM, Suh I, Woodward M . Cigarette smoking, systolic blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. Stroke 2008; 39: 1694–1702.

Ishikawa S, Kario K, Kayaba K, Gotoh T, Nago N, Nakamura Y, Tsutsumi A, Kajii E . Linear relationship between blood pressure and stroke: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007; 9: 677–683.

Feigin V, Parag V, Lawes CM, Rodgers A, Suh I, Woodward M, Jamrozik K, Ueshima H . Smoking and elevated blood pressure are the most important risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage in the Asia-Pacific region: an overview of 26 cohorts involving 306,620 participants. Stroke 2005; 36: 1360–1365.

Sauvaget C, Ramadas K, Thomas G, Thara S, Sankaranarayanan R . Prognosis criteria of casual systolic and diastolic blood pressure values in a prospective study in India. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010; 64: 366–372.

O'Seaghdha CM, Perkovic V, Lam TH, McGinn S, Barzi F, Gu DF, Cass A, Suh I, Muntner P, Giles GG, Ueshima H, Woodward M, Huxley R . Blood pressure is a major risk factor for renal death: an analysis of 560 352 participants from the Asia-Pacific region. Hypertension 2009; 54: 509–515.

Ogihara T, Nakao K, Fukui T, Fukiyama K, Fujimoto A, Ueshima K, Oba K, Shimamoto K, Matsuoka H, Saruta T . The optimal target blood pressure for antihypertensive treatment in Japanese elderly patients with high-risk hypertension: a subanalysis of the Candesartan Antihypertensive Survival Evaluation in Japan (CASE-J) trial. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 1595–1601.

Kagiyama S, Fukuhara M, Ansai T, Matsumura K, Soh I, Takata Y, Sonoki K, Awano S, Takehara T, Iida M . Association between blood pressure and mortality in 80-year-old subjects from a population-based prospective study in Japan. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 265–270.

Huxley R, Woodward M, Barzi F, Wong JW, Pan WH, Patel A Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Does sex matter in the associations between classic risk factors and fatal coronary heart disease in populations from the Asia-Pacific region? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005; 14: 820–828.

Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA . Comparison of active treatment and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. J Hypertens 1998; 16: 1823–1829.

Wang JG, Staessen JA, Gong L, Liu L . Chinese trial on isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 211–220.

Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Li W, Zhang X, Zanchetti A FEVER Study Group. The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER) Study: a randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens 2005; 23: 2157–2172.

Ratnasabapathy Y, Lawes CM, Anderson CS . The Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS): clinical implications for older patients with cerebrovascular disease. Drugs Aging 2003; 20: 241–251.

Matsuzaki M, Ogihara T, Umemoto S, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimada K, Abe K, Suzuki N, Eto T, Higaki J, Ito S, Kamiya A, Kikuchi K, Suzuki H, Tei C, Ohashi Y, Saruta T . Prevention of cardiovascular events with calcium channel blocker-based combination therapies in patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 1649–1659.

Yui Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kodama K, Hirayama A, Nonogi H, Kanmatsuse K, Origasa H, Iimura O, Ishii M, Saruta T, Arakawa K, Hosoda S, Kawai C . Comparison of nifedipine retard with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Japanese hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: the Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B (JMIC-B) randomized trial. Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 181–191.

Ogihara T . Practitioner's trial on the efficacy of antihypertensive treatment in the elderly hypertension (the PATE-Hypertension Study) in Japan. Am J Hypertens 2000; 13: 461–467.

Ogihara T, Saruta T, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Fujita T, Shimada K, Imai Y, Nishigaki M . Valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension (VALISH) study: rationale and design. Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 657–661.

Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Shimada K, Imai Y, Kikuchi K, Ito S, Eto T, Kimura G, Imaizumi T, Takishita S, Ueshima H . Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension 2010; 56: 196–202.

JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 2115–2127.

Fujita T, Wu Z, Park J-B, Chen M-F . Briefings on JHS, CHS, KHS and THS guidelines and their difference from JNC VII and ESC/ESH. Int J Clin Pract 2006; 60: 3–6.

Morgan T . Hypertension in the Asian Pacific region: the problem and the solution http://www.apsh.org/Beij_report.doc (accessed 10 June 2014).

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf (accessed 10 June 2014).

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De BG, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F . 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1281–1357.

Liu LS Writing Group of 2010. Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2011; 39: 579–615.

Park JB . 2004 Korean hypertension treatment guideline and its perspective. Korean Circulation J 2006; 36: 405–410.

Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ishimitsu T, Ito M, Ito S, Itoh H, Iwao H, Kai H, Kario K, Kashihara N, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Kohara K, Komuro I, Kumagai H, Matsuura H, Miura K, Morishita R, Naruse M, Node K, Ohya Y, Rakugi H, Saito I, Saitoh S, Shimada K, Shimosawa T, Suzuki H, Tamura K, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Umemura S . Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res 2014; 37: 253–387.

Wang L . Physician-related barriers to hypertension management. Med Princ Pract 2004; 13: 282–285.

Cheng H . Prescribing pattern of antihypertensive drugs in a general hospital in central China. Int J Clin Pharm 2011; 33: 215–220.

Wang JG, Kario K, Lau T, Wei YQ, Park CG, Kim CH, Huang J, Zhang W, Li Y, Yan P, Hu D . Use of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in the management of hypertension in Eastern Asians: a scientific statement from the Asian Pacific Heart Association. Hypertens Res 2011; 34: 423–430.

Mori H, Ukai H, Yamamoto H, Saitou S, Hirao K, Yamauchi M, Umemura S . Current status of antihypertensive prescription and associated blood pressure control in Japan. Hypertens Res 2006; 29: 143–151.

Huang LY, Shau WY, Chen HC, Su S, Yang MC, Yeh HL, Lai MS . Pattern analysis and variations in the utilization of antihypertensive drugs in Taiwan: a six-year study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013; 17: 410–419.

Liu PH, Wang JD . Antihypertensive medication prescription patterns and time trends for newly-diagnosed uncomplicated hypertension patients in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 133.

Sung SK, Lee SG, Lee KS, Kim DS, Kim KH, Kim KY . First-year treatment adherence among outpatients initiating antihypertensive medication in Korea: results of a retrospective claims review. Clin Ther 2009; 31: 1309–1320.

Zhou BF, Stamler J, Dennis B, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okuda N, Robertson C, Zhao L, Chan Q, Elliott P . Nutrient intakes of middle-aged men and women in China, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States in the late 1990s: the INTERMAP study. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17: 623–630.

Wang JG, Zeng WF, He YS, Chen LL, Wei M, Li ZP, Zhang BW, Li Y . Valsartan/amlodipine compared to nifedipine GITS in patients with hypertension inadequately controlled by monotherapy. Adv Ther 2013; 30: 771–783.

Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ . Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ 2009; 338: b1665.

Zhao X, Li S, Ba S, He F, Li N, Ke L, Li X, Lam C, Yan LL, Zhou Y, Wu Y . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among herdsmen living at 4,300 m in Tibet. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25: 583–589.

Li H, Meng Q, Sun X, Salter A, Briggs NE, Hiller JE . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural China: results from Shandong Province. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 432–438.

Tian S, Dong GH, Wang D, Liu MM, Lin Q, Meng XJ, Xu LX, Hou H, Ren YF . Factors associated with prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in urban adults from 33 communities in China: the CHPSNE Study. Hypertens Res 2011; 34: 1087–1092.

Sun Z, Zheng L, Detrano R, Zhang X, Xu C, Li J, Hu D, Sun Y . Incidence and predictors of hypertension among rural Chinese adults: results from Liaoning province. Ann Fam Med 2010; 8: 19–24.

Dong GH, Sun ZQ, Zhang XZ, Li JJ, Zheng LQ, Li J, Hu DY, Sun YX . Prevalence, awareness, treatment & control of hypertension in rural Liaoning province, China. Indian J Med Res 2008; 128: 122–127.

Hatori N, Sato K, Miyakawa M, Mitani K, Miyajima M, Yuasa S, Furuki T, Matsuba I, Naka K . The current status of blood pressure control among patients with hypertension: a survey of actual clinical practice. J Nippon Med Sch 2012; 79: 69–78.

Wang JG, Li Y . Characteristics of hypertension in Chinese and their relevance for the choice of antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012; 28: 67–72.

Jonas JB, Nangia V, Matin A, Joshi PP, Ughade SN . Prevalence, awareness, control, and associations of arterial hypertension in a rural central India population: the Central India Eye and Medical Study. Am J Hypertens 2010; 23: 347–350.

Taylor EN, Hu FB, Curhan GC . Antihypertensive medications and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1063–1070.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, Ferdinand KC, Ann FM, Frishman WH, Jaigobin C, Kostis JB, Mancia G, Oparil S, Ortiz E, Reisin E, Rich MW, Schocken DD, Weber MA, Wesley DJ . ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011 57: 2037–2114.

Matsumura K, Arima H, Tominaga M, Ohtsubo T, Sasaguri T, Fujii K, Fukuhara M, Uezono K, Morinaga Y, Ohta Y, Otonari T, Kawasaki J, Kato I, Tsuchihashi T . Impact of antihypertensive medication adherence on blood pressure control in hypertension: the COMFORT study. QJM 2013; 106: 909–914.

Franklin SS . Elderly hypertensives: how are they different? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012; 14: 779–786.

Prisant LM (ed). Hypertension in the Elderly. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA. 2005.

Aung MN, Lorga T, Srikrajang J, Promtingkran N, Kreuangchai S, Tonpanya W, Vivarakanon P, Jaiin P, Praipaksin N, Payaprom A . Assessing awareness and knowledge of hypertension in an at-risk population in the Karen ethnic rural community, Thasongyang, Thailand. Int J Gen Med 2012; 5: 553–561.

Park YH, Kim H, Jang SN, Koh CK . Predictors of adherence to medication in older Korean patients with hypertension. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013; 12: 17–24.

Almas A, Godil SS, Lalani S, Samani ZA, Khan AH . Good knowledge about hypertension is linked to better control of hypertension; a multicentre cross sectional study in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes 2012; 5: 579.

Kario K, Robbins J, Jeffers BW . Titration of amlodipine to higher doses: a comparison of Asian and Western experience. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2013; 9: 695–701.

Kagiyama S, Takata Y, Ansai T, Matsumura K, Soh I, Awano S, Sonoki K, Yoshida A, Torisu T, Hamasaki T, Nakamichi I, Takehara T, Iida M . Does decreased diastolic blood pressure associate with increased mortality in 80-year-old Japanese? Clin Exp Hypertens 2009; 31: 639–647.

Chongsuvivatwong V, Phua KH, Yap MT, Pocock NS, Hashim JH, Chhem R, Wilopo SA, Lopez AD . Health and health-care systems in southeast Asia: diversity and transitions. Lancet 2011; 377: 429–437.

Pongwecharak J, Treeranurat T . Lifestyle changes for prehypertension with other cardiovascular risk factors: findings from Thailand. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2011; 51: 719–726.

Mendis S, Johnston SC, Fan W, Oladapo O, Cameron A, Faramawi MF . Cardiovascular risk management and its impact on hypertension control in primary care in low-resource settings: a cluster-randomized trial. Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88: 412–429.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, O'Donnell CJ, Roccella EJ, Levy D . Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure: factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension 2000; 36: 594–599.

Williams B . Evolution of hypertensive disease: a revolution in guidelines. Lancet 2006; 368: 6–8.

Guerin AP, Blacher J, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM . Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failure. Circulation 2001; 103: 987–992.

Briet M, Schiffrin EL . Treatment of arterial remodeling in essential hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2013; 15: 3–9.

Laurent S, Schlaich M, Esler M . New drugs, procedures, and devices for hypertension. Lancet 2012; 380: 591–600.

Segura J, Salazar J, Ruilope LM . Dual neurohormonal intervention in CV disease: angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2013; 22: 915–925.

Paulis L, Steckelings UM, Unger T . Key advances in antihypertensive treatment. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012; 9: 276–285.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gregor Fyfe and Chris Cammack of CircleScience, part of KnowledgePoint360, an Ashfield Company, and Tamsin Williamson (a freelance medical writer contracted to CircleScience) for providing writing assistance, which was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Professor Park reports no conflicts of interest. Professor Kario reports receiving research funding from Novartis. Professor Wang reports receiving honoraria from Pfizer for lectures and article contributions, and receiving research funding from Pfizer and Novartis.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Kario, K. & Wang, JG. Systolic hypertension: an increasing clinical challenge in Asia. Hypertens Res 38, 227–236 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.169

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.169

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Network meta-analysis of sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of essential hypertension

Clinical Research in Cardiology (2023)

-

Sacubitril/Valsartan in Heart Failure with Hypertension Patients: Real-World Experiences on Different Ages, Drug Doses, and Renal Functions

High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention (2023)

-

STEP to blood pressure management of elderly hypertension: evidence from Asia

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

RSSDI Guidelines for the management of hypertension in patients with diabetes mellitus

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2022)

-

A geodatabase of blood pressure level and the associated factors including lifestyle, nutritional, air pollution, and urban greenspace

BMC Research Notes (2021)