Abstract

To clarify the possible association of frailty with hypertension prevalence, treatment and blood pressure (BP) control in the elderly, we conducted a screening survey of 1091 elderly community-dwelling subjects aged ⩾65 years, using data from public health check-ups and frailty was determined by a 25-item questionnaire, the Basic Checklist for Frailty (BCF). The significance of differences in the association of BCF categories or BCF items with each hypertension status was analyzed using multiple logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, sex and possible confounding underlying chronic conditions. A total of 63% of subjects were hypertensive (BP⩾140/90 mm Hg), and of those, 85% were receiving antihypertensive treatment, and 56.0% of those receiving treatment had controlled BP (<140/90 mm Hg). BCF categories that showed an independent association with hypertension status were ‘impaired walking status’ and absence of ‘impaired nutritional status’ for prevalence of hypertension, ‘impaired instrumental activity of daily living status’ and ‘impaired nutritional status’ for untreated hypertension among hypertensives and ‘impaired oral function’ for BP-uncontrolled hypertension among treated hypertensives. In addition, BCF items that showed an independent association were ‘inability to walk for more than 15 min without rest’ and absence of ‘Body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg m−2’ for prevalence of hypertension, ‘weight loss of more than 2–3 kg in the past 6 months’ for untreated hypertension, and ‘difficulty eating hard food’ for BP-uncontrolled hypertension. These observations indicate that assessment of these specified frailty categories and/or items may be useful for evaluating hypertension status in elderly community-dwelling subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Providing high quality care to older adults with hypertension is growing in importance because of improved survival of patients with hypertension into old age and a growing older population at risk of developing hypertension.1 Many large-scale intervention trials have proven the necessity of treatment of hypertension in the elderly, including isolated systolic hypertension. Meta-analyses of large-scale intervention trials for elderly hypertensive patients aged 60 years and older,2 as well as for those aged 80 years and older,3 have revealed significant reductions in morbidity and/or mortality of cerebro-cardiovascular disease by antihypertensive treatment. Moreover, the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial directly and clearly revealed a beneficial effect of antihypertensive treatment even in those aged 80 years and older.4

Trends in hypertension prevalence, treatment and control over time have been reported in US adults,5 including those aged 60 and older6 using data from two independent national surveys: the National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey (NHANES) III (1988–1994) and the current NHANES (1999–2004). The older population with hypertension has been reported to have poorer blood pressure (BP) control than younger populations in the US.7, 8 The prevalence of hypertension in community-dwelling Japanese has also been reported to increase with age from 20 years through 80 years, reaching 50% and higher at 75 years of age and older in both sexes.9 However, little is reported about trends in the treatment and BP-control of hypertension in elderly community-dwelling subjects in Japan.

On the other hand, hypertension is also known to be linked with frailty in the elderly, as assessed by weight loss, low activities of daily living (ADL), low instrumental ADL (IADL) and low physical activity.10, 11 In Japan, the public long-term care insurance system provides services to older adults who have been certified as requiring support (levels 1–2) or care (levels 1–5). Uncertified older adults with impaired health who are considered at high risk for needing support/care (frail elderly) are provided with preventive care services by municipalities.12 Uncertified elderly subjects are given an annual health check-up by the local government, and frailty is examined using the Basic Checklist for Frailty (BCF), a yes-no questionnaire consisting of simple assessments for seven categories of frailty; impaired IADL status (five items), impaired walking status (five items), impaired nutritional status (two items), impaired oral function (three items), staying indoors (two items), impaired memory status (three items) and depressed mood (five items). However, few studies have examined the association of hypertension prevalence, treatment and BP-control with frailty in the elderly. Therefore, this study examined the relationship between hypertension status, and BCF categories or items in elderly community-dwelling subjects. We also studied whether this relationship could be explained by underlying chronic conditions.

Methods

Subjects

In April 2008, the Regional Comprehensive Support Center of Uchinada-Town, Ishikawa, Japan distributed the BCF to all uncertified elderly community-dwelling subjects aged ⩾65 years. The local government also provided a Public Health Center-based annual health check-up to these elderly subjects. Data were collected by the Uchinada-Town local government after depersonalizing participant data to ensure anonymity. We excluded elderly subjects who were already certified for long-term care insurance at the baseline. The study was formally approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kanazawa Medical University.

Baseline examinations

A self-administered questionnaire that included medical history, smoking condition (yes/no), regular alcohol drinking (yes/no) and time since the last meal13 was completed at baseline. BMI, kg m−2 was calculated as weight divided by height squared. The blood condition was defined as fasting if blood was collected more than 8 h after the last meal. Serum levels of Cr, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose were measured using an automated spectrometer. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate, calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation14 with coefficients modified for Japanese patients,15 194 × Cr−1.094 × age−0.287 ( × 0.739 if female), <60 ml min–1 1.73 m−2. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting blood glucose ⩾7.0 mmol l−1 (126 mg dl−1), a non-fasting glucose level ⩾11.1 mmol l−1 (200 mg dl−1), HbA1c ⩾6.5% by a standardized method, or use of hypoglycemic agents and/or insulin.16 Dyslipidemia was defined as fasting plasma total cholesterol level ⩾5.72 mmol l−1 (220 mg dl−1), triglycerides ⩾1.70 mmol l−1 (150 mg dl−1), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1.04 mmol l−1 (40 mg dl−1), or use of lipid-lowering agents.17

Hypertension status

Baseline BP was measured at least twice from the right arm of seated participants who had rested for more than 5 min, by trained observers using standard mercury sphygmomanometers. When the difference in the two measurements of systolic BP was greater than 5 mm Hg, another measurement was performed.18 The mean of the last two stable measurements was used for analyses. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ⩾140 mm Hg, diastolic BP ⩾90 mm Hg, or current antihypertensive drug treatment. Treatment was defined as reported current use of antihypertensive drug therapy. BP-control was defined as antihypertensive drug treatment associated with systolic BP <140 and diastolic BP <90 mm Hg.

Statistical methods

For comparison of two groups, we used univariate analysis including χ2 test (Fisher’s exact test when needed) for comparing categorical variables and nonparametric Mann–Whitney U statistics for comparing the distributions of ordinal variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify frailty factors independently associated with any of prevalence of hypertension among all elderly subjects, untreated hypertension among hypertensive subjects and BP-uncontrolled hypertension among treated hypertensive subjects, after adjustment for age, sex and associated variables by univariate analysis. Common pitfalls associated with multivariate regression were avoided as described by Concato et al.19 Associated variables were selected from the data sets of status of smoking and alcohol intake, past history of stroke and ischemic heart disease, presence of CKD, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia and either the seven BCF categories (model-1) or the 25 questionnaire items (model-2), according to their univariate analysis P-value (<0.20) to avoid common pitfalls associated with multivariate regression.19 Estimates for odds ratio and corresponding two-sided 95% confidence interval demonstrating statistical significance were derived from the regression model. Data were analyzed using SPSS (v. 16.0, Chicago, IL, USA). A probability of P<0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Study population

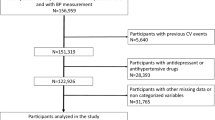

A primary screening questionnaire survey was conducted on all 4050 uncertified elderly community-dwelling subjects, aged ⩾65 years, living in a town in Ishikawa, Japan. Out of 3150 (77.8%) subjects who replied to the questionnaire, 1091 (427 men and 664 women) supplied complete information on all study variables, including the health check-up and were included in our study. The age of subjects (mean±s.d.) was 73.5±6.1 years (65–94 years). In the 1091 included individuals, the significance of differences in clinical factors was analyzed using univariate (Table 1) and multivariate (Tables 2 and 3) comparisons of hypertensives (n=683) and normotensives (n=408), untreated (n=104) and treated (n=579) hypertensives and BP-uncontrolled (n=255) and BP-controlled (n=324) treated hypertensives (Figure 1). A total of 62.6% of subjects were hypertensive, and of those, 84.8% were receiving antihypertensive drug treatment and BP was controlled in 56.0% of those undergoing treatment. Overall, 47.4% of hypertensive patients had controlled BP.

Baseline factors and BCF categories and items

Compared with non-hypertensive elderly subjects, hypertensive subjects were older, and showed a higher prevalence of concomitant diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia in univariate analysis (Table 1). Moreover, hypertensive subjects were less active and less thin than non-hypertensive subjects, as shown by associations with ‘impaired walking status’ and absence of ‘impaired nutritional status’ in the BCF categories, and associations with six BCF items including one IADL item, four items of ‘impaired walking status’ and absence of ‘BMI <18.5 kg m−2’ in univariate analysis (Table 1). Multiple logistic analysis using these BCF categories selected by univariate P-values<0.20 (model-1) revealed that two BCF categories, ‘impaired walking status’ and absence of ‘impaired nutritional status’, besides older age and diabetes mellitus, showed statistically significant association with prevalence of hypertension in elderly subjects (Table 2). In multiple logistic analysis using model-2 sets, two BCF items, ‘inability to walk for more than 15 min without rest’ and absence of ‘BMI <18.5 kg m−2’, besides older age and diabetes mellitus, showed statistically significant association with prevalence of hypertension in elderly subjects (Table 3).

In contrast to the entire hypertensive subjects, untreated hypertensive subjects were associated not only with clinical factors, namely absence of CKD or dyslipidemia and female sex, but also with one BCF category, ‘impaired nutritional state’ and with eight BCF items, including four out of five IADL items: ‘able to stand up’, ‘weight loss of more than 2–3 kg in the past 6 months’, ‘going out more than once a week’ and ‘able to make a phone call’, compared with treated hypertensive subjects in univariate analysis (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis using model-1 sets revealed that two BCF categories, ‘impaired IADL status’ and ‘impaired nutritional status’, besides absence of CKD or dyslipidemia, showed a statistically significant association with untreated hypertension in elderly hypertensive subjects (Table 2). In addition, logistic regression analysis using model-2 sets revealed that ‘weight loss of more than 2–3 kg in the past 6 months’ among these BCF items, besides absence of CKD or dyslipidemia, showed statistically significant association with untreated hypertension in elderly hypertensive subjects (Table 3).

Among treated hypertensive subjects, hypertensive subjects with uncontrolled BP (>140/90 mm Hg) showed a similar profile of factors in baseline examinations and in BCF categories and items, except one BCF item, ‘difficulty eating hard food’, compared with hypertensive subjects with controlled BP in univariate analysis (Table 1). Logistic regression analyses revealed that ‘impaired oral function’ among the BCF categories in model-1 analysis (Table 2) and ‘difficulty eating hard food’ among the BCF items in model-2 analysis (Table 3) showed a statistically significant association with untreated hypertension in elderly community-dwelling subjects.

Discussion

The present study newly disclosed an emerging profile of hypertension status and frailty in elderly community-dwelling subjects based on data from a Public Health Center survey and Regional Comprehensive Support Center in a town in Japan. The prevalence of hypertension (62.6%) in the present study in elderly community-dwelling Japanese subjects aged 65 years and older was comparable to the result (67%) in those aged 60 years and older in NHANES 1999–2004 in the US6 and to that (⩾50%) in those aged 75 years and older in Japan.9 On the other hand, the rate of untreated hypertension in the present study, 15.2% of elderly hypertensive subjects aged 65 years and older, was rather low compared with the results in the US; 33% of those aged 60 years and older in NHANES 1999–20046 and 52% of those ⩾18 years of age (mean age 58–60 years) in NHANES 1988–2008.5 Moreover, the rate of BP-uncontrolled hypertension in the present study, 44% of treated hypertensive subjects aged 65 years and older, was also low compared with that in the US; 57% of those aged 60 years and older6 and 53–73% of those ⩾18 years of age.5 These differences may be reflected by the major fall of BP level recently achieved in community-dwelling subjects in Japan.20

Clinical factors independently associated with the prevalence of hypertension and with untreated hypertension in the present study were similar to those previously reported in community-dwelling subjects in the US, namely older age6 and presence of diabetes mellitus6 for prevalence of hypertension and absence of CKD5, 6 and absence of dyslipidemia5 for untreated hypertension.

Logistic regression analysis in the present study also revealed that specified BCF categories and/or items were independently associated with hypertension status. First, two BCF categories, ‘impaired walking status’ and absence of ‘impaired nutritional status’, besides presence of diabetes mellitus, were independently associated with prevalence of hypertension in elderly subjects in logistic analysis using model-1 data sets. In addition, two BCF items, ‘inability to walk for more than 15 min without a rest’ and absence of ‘BMI <18.5 kg m−2’, were further shown to have an independent association with prevalence of hypertension in elderly subjects in logistic analysis using model-2 data sets. A possible explanation for the association of ‘impaired walking status’ or ‘inability to walk for more than 15 min without rest’ with prevalence of hypertension is that hypertension itself may cause physical frailty resulting in a decline in walking ability in the elderly, since elderly subjects with frailty syndrome with low physical activity had higher BP than the non-frailty group,11 and since hypertension was independently associated with shorter distance on the 6-minute walk test in elderly subjects.21 Another possible explanation is that daily practice of walking may prevent hypertension even in the elderly population, since subjects walking 1 hour or more per day had a lower prevalence of hypertension in a large population of frail and very old subjects living in the community.22 On the other hand, the observation in the present study of the independent association of thinness (BMI <18.5 kg m−2) with lower prevalence of hypertension in the elderly is partly compatible with a previous report of an association of being underweight (BMI <20 kg m−2) with lower prevalence of hypertension in elderly subjects,23 although it is well-known that BMI greater than the reference value (25 kg m−2) is independently associated with a greater likelihood of hypertension in the elderly.6

Second, two BCF categories, ‘impaired IADL status’ and ‘impaired nutritional status’, besides absence of CKD or dyslipidemia, were independently associated with untreated hypertension in hypertensive elderly subjects. The latter finding was further supported by the independent association of ‘weight loss of more than 2–3 kg in the past 6 months’ in model-2 logistic analysis using BCF items (Table 3). Although the precise mechanism of the association of ‘impaired IADL status’ with untreated hypertension in the elderly is unknown, IADL is a well-known indicator of the ability to live independently in the community. Okamura et al.24 reported that elderly residents with systolic hypertension (⩾160 mm Hg) in two communities located in Akita and Kochi Prefectures showed a 3.41 times higher odds ratio for having low IADL scores than those with normal BP. Hayakawa et al.25 reported a significant relationship between decrease in IADL score and cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus and smoking, in a cohort in Japan. The present observation of an association between decline in IADL score and untreated hypertension is, at least in part, compatible with the reports of Okamura et al.24 and Hayakawa et al.25 Therefore, active treatment of hypertension in elderly community-dwelling subjects may be linked to prevention of future decline in IADL in Japanese elderly, allowing them to live a healthy and active life. On the other hand, the precise mechanism of the independent association of weight loss (of more than 2–3 kg in the past 6 months) with untreated hypertension in hypertensive elderly subjects is also unknown. One of the possible explanations for this is that weight loss as opposed to weight gain may often be overlooked as a problem linked to hypertension by healthcare providers, the public and elderly subjects themselves, as BMI <25 kg m−2 compared with BMI ⩾25 kg m−2 was reported to be independently associated with a greater likelihood of untreated hypertension in elderly subjects in the US.6 Another possibility is that weight loss more often observed in elderly subjects with untreated hypertension might be caused by past antihypertensive drug treatment and result in cessation of drug treatment by elderly subjects themselves, as unintended weight loss in the elderly may be caused by polypharmacy through dysgeusia and anorexia due to many individual medications.26

Third, ‘impaired oral function’ in the BCF categories and ‘difficulty eating hard food’ in the BCF items were independently associated with BP-uncontrolled hypertension in treated hypertensive elderly subjects in respective logistic regression analysis models. One of the possible explanations for this is that oral dysfunction may directly cause trouble swallowing pills, resulting in underuse of antihypertensive medication in these subjects.27 Another possibility is that periodontal disease may cause both ‘difficulty eating hard food’ and BP-uncontrolled hypertension. The severity of periodontal disease28, 29 and tooth loss due to the disease30 were significantly related to hypertension independent of age, although inconsistent results were also reported in middle-aged men.31 Moreover, periodontal disease is reported to contribute to poor BP control in subjects aged 70 years and older.32

In the present study, specified BCF categories and/or items were newly identified as factors independently associated with prevalence of hypertension, untreated hypertension and BP-uncontrolled hypertension in elderly community-dwelling subjects. These frailty categories and items may be useful for evaluating hypertension status in elderly community-dwelling subjects. However, in view of the single community model, care must be taken in interpreting these results, and further evaluation in multi-regional trials is needed. Frailty assessed by comprehensive geriatric assessments and a precise health examination should be included in future studies to elucidate the mechanisms of the individual associations of BCF categories/items and hypertension status. Stratified sampling of BCF scores according to the kinds of antihypertensive drugs used, including renin-angiotensin blockers, is also needed in future studies, because the renin-angiotensin system is thought to have a crucial role in aging and/or frailty.33

References

Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G . Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 2269–2276.

Insua JT, Sacks HS, Lau TS, Lau J, Reitman D, Pagano D, Chalmers TC . Drug treatment of hypertension in the elderly: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121: 355–362.

Gueyffier F, Bulpitt C, Boissel JP, Schron E, Ekbom T, Fagard R, Casiglia E, Kerlikowske K, Coope J . Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: a subgroup meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. INDANA Group. Lancet 1999; 353: 793–796.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, Belhani A, Forette F, Rajkumar C, Thijs L, Banya W, Bulpitt CJ . Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1887–1898.

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN, Brzezinski WA, Ferdinand KC . Uncontrolled and apparent treatment resistant hypertension in the United States, 1988–2008. Circulation 2011; 124: 1046–1058.

Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S . Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–2004. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 1056–1065.

Hajjar I, Kotchen TA . Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 2003; 290: 199–206.

Borzecki AM, Wong AT, Hickey EC, Ash AS, Berlowitz DR . Hypertension control: How well are we doing? Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 2705–2711.

Kuzuya M, Ando F, Iguchi A, Shimokata H . Age-specific change of prevalence of metabolic syndrome: longitudinal observation of large Japanese cohort. Atherosclerosis 2007; 191: 305–312.

Wang L, van Belle G, Kukull WB, Larson EB . Predictors of functional change: a longitudinal study of nondemented people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1525–1534.

Bastos-Barbosa RG, Ferriolli E, Coelho EB, Moriguti JC, Nobre F, da Costa Lima NK . Association of frailty syndrome in the elderly with higher blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25: 1156–1161.

Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N . Japan’s universal long-term care system reform of 2005: Containing costs and realizing a vision. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 1458–1463.

Saito I, Kokubo Y, Yamagishi K, Iso H, Inoue M, Tsugane S . Diabetes and the risk of coronary heart disease in the general Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective (JPHC) study. Atherosclerosis 2011; 216: 187–191.

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D . Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 461–470.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Yokoyama H, Hishida A . On behalf of the collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 982–992.

Kuzuya T, Nakagawa S, Satoh J, Kanazawa Y, Iwamoto Y, Kobayashi M, Nanjo K, Sasaki A, Seino Y, Ito C, Shima K, Nonaka K, Kadowaki T . Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. Report of the Committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2002; 55: 65–85.

Bando Y, Kanehara H, Aoki K, Katoh K, Toya D, Tanaka N . Characteristics of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in a population undergoing health screening in Japan: target populations for efficient screening. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009; 83: 341–346.

Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H . Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 3–107.

Concato J, Feinstein AR, Holford TR . The risk of determining risk with multivariable models. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 201–210.

Ueshima H . Explanation for the Japanese paradox: prevention of increase in coronary heart disease and reduction in stroke. J Atheroscler Thromb 2007; 14: 278–286.

Enright PL, McBurnie MA, Bittner V, Tracy RP, McNamara R, Arnold A, Newman AB . Cardiovascular Health Study. The 6-min walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest 2003; 123: 387–398.

Landi F, Russo A, Cesari M, Pahor M, Liperoti R, Danese P, Bernabei R, Onder G . Walking one hour or more per day prevented mortality among older persons: results from ilSIRENTE study. Prev Med 2008; 47: 422–426.

Barreto SM, Passos VM, Lima-Costa MF . Obesity and underweight among Brazilian elderly: the Bambuí Health and Aging Study. Cad Saude Publica 2003; 19: 605–612.

Okamura T, Sato S, Kiyama A, Nakagawa Y, Naito Y, Iida M, Iso H, Shimamoto T, Komachi Y . Follow-up study on the relationship between the findings of cardiovascular screening, and prognosis for life and the capacity of activity in the elderly (65–74 years). Kosei-No-Shihyou 1977; 44: 18–24 in Japanese.

Hayakawa T, Okamura T, Okayama A, Kanda H, Watanabe M, Kita Y, Miura K, Ueshima H . Relationship between 5-year decline in instrumental activity of daily living and accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors: NIPPON DATA90. J Atheroscler Thromb 2010; 17: 64–72.

Huffman GB . Evaluating and treating unintentional weight loss in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 2002; 65: 640–650.

Carnaby-Mann G, Crary M . Pill swallowing by adults with dysphagia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005; 131: 970–975.

Holmlund A, Holm G, Lind L . Severity of periodontal disease and number of remaining teeth are related to the prevalence of myocardial infarction and hypertension in a study based on 4254 subjects. J Periodontol 2006; 77: 1173–1178.

Morita T, Yamazaki Y, Mita A, Takada K, Seto M, Nishinoue N, Sasaki Y, Motohashi M, Maeno M . A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol 2010; 81: 512–519.

Al-Shammari KF, Al-Khabbaz AK, Al-Ansari JM, Neiva R, Wang HL . Risk indicators for tooth loss due to periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 1910–1918.

Rivas-Tumanyan S, Spiegelman D, Curhan GC, Forman JP, Joshipura KJ . Periodontal disease and incidence of hypertension in the health professionals follow-up study. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25: 770–776.

Rivas-Tumanyan S, Campos M, Zevallos JC, Joshipura KJ . Periodontal disease, hypertension and blood pressure among older adults in Puerto Rico. J Periodontol 2013; 84: 203–211.

Abadir PM . The frail renin-angiotensin system. Clin Geriatr Med 2011; 27: 53–65.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (23-33) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG) Japan, Comprehensive Research on Aging and Health, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, a Grant of Strategic Research Project (H2012-15 [S1201022]) from Kanazawa Medical University and grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koizumi, Y., Hamazaki, Y., Okuro, M. et al. Association between hypertension status and the screening test for frailty in elderly community-dwelling Japanese. Hypertens Res 36, 639–644 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between Frailty and Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment, and Control in the Elderly Korean Population

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Association between blood pressure and disability-free survival among community-dwelling elderly patients receiving antihypertensive treatment

Hypertension Research (2014)