Abstract

The CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, that is, ischemic stroke risk indices for patients having atrial fibrillation (AF), may also be useful as bleeding risk indices. Japanese patients with AF, who routinely took oral antithrombotic agents were enrolled from a prospective, multicenter study. The CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were assessed based on information at entry. Scores of 0, 1 and ⩾2 were defined as the low, intermediate and high ischemic risk categories, respectively, for each index. Of 1221 patients, 873 took warfarin, 114 took antiplatelet agents and 234 took both. The annual incidence of ischemic stroke was 0.76% in the low-risk category, 1.46% in the intermediate-risk category and 2.90% in the high-risk category by CHADS2 scores, and 1.44, 0.42 and 2.50%, respectively, by CHA2DS2-VASc scores. The annual incidence of major bleeding in each category was 1.52, 2.19 and 2.25% by CHADS2, and 1.44, 1.69 and 2.24% by CHA2DS2-VASc. After multivariate adjustment, the CHADS2 was associated with ischemia (odds ratio 1.76, 95% confidence interval 1.03–3.38 per 1−category increase) and the CHA2DS2-VASc tended to be associated with ischemia (2.18, 0.89–8.43). On the other hand, associations of the indices with bleeding were weak. In conclusion, bleeding risk increased gradually as the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores increased in Japanese antithrombotic users, although the statistical impact was rather weak compared with their predictive power for ischemic stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Decision-making for thromboprophylaxis needs to balance the risk of ischemic stroke against the risk of major bleeding.1 Known bleeding risk scores such as HEMORR2HAGES and HAS-BLED include hypertension, advanced age and history of stroke as their components,2, 3 which are also known risk factors for ischemic stroke and compose the stroke risk scores for patients having atrial fibrillation (AF), such as the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores.4, 5 Thus, the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores may also be useful as bleeding risk indices.

To determine the incidence and severity of bleeding complications in patients with cardiovascular diseases and stroke treated with oral antithrombotic therapy in Japan, a prospective, multicenter, observational study (the Bleeding with Antithrombotic Therapy (BAT) Study) was conducted. In its initial report of the overall results, adding antiplatelet agents to warfarin or single antiplatelet therapy doubled the risk of life-threatening or major bleeding events.6 In the second report, an increase in blood pressure levels during antithrombotic medication was positively associated with the development of intracerebral hemorrhage.7 The series of the findings from the BAT register indicate that patients who require pharmacotherapeutic prevention from ischemic events are also high-risk subjects for bleeding events. Thus, it is important to ascertain the power of known ischemia-risk indices for prediction of bleeding events.

The associations between the CHADS2/CHA2DS2-VASc scores of AF patients and the development of bleeding events, as well as ischemic stroke, were examined in the present study.

Methods

A total of 4009 patients (2728 men, 69±10 years old) who were taking oral antiplatelet agents or warfarin for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases were enrolled in the BAT Study from 19 stroke and cardiovascular centers in Japan (see Appendix) and were observed for 2–30 months between October 2003 and March 2006. The study protocol, inclusion/exclusion criteria and general results were published previously.6, 7 The medical ethics review boards of the participating institutes approved the study protocol, and all patients provided their written informed consent.

In the present sub-study, AF patients were enrolled from the BAT register. AF was defined by a diagnosis at entry based on a confirmed history or identification on ECG. Baseline data included components of the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, as well as of neoplasm, liver cirrhosis, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking, alcohol consumption, systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels and antithrombotic medication at entry. Definitions of these comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors were the same as those in the previous study.6 Scores of 0, 1 and ⩾2 were defined as the low, intermediate and high ischemic risk categories, respectively, for each index.5, 8

The outcomes included ischemic stroke and bleeding events during the observation period. Bleeding events were defined as life-threatening or major bleeding events according to the definition by the Management of ATherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with recent transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke study.9 Briefly, life-threatening bleeding was defined as any fatal bleeding event, a drop in hemoglobin of ⩾50 g l−1, hemorrhagic shock, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage or transfusion of ⩾4 units of red blood cells. Major bleeding was defined as significantly disabling, severe intraocular bleeding or transfusion of ⩽3 units of red blood cells. Secondary hemorrhagic transformation of an ischemic stroke was not regarded as a bleeding event.

Statistics

All analyses were performed using the JMP 8 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To compare baseline clinical characteristics among the three ischemic risk categories according to the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, one-way factorial analysis of variance with post-hoc comparison by Dunnett’s test (with the high-risk category as control) was used for continuous variables and the χ2-test was used for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using a forced entry method of baseline clinical characteristics to examine the associations of the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores with risks of ischemic stroke and bleeding events, as well as to examine those of the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 1221 patients (376 women, 70±10 years old (mean±s.d.)) were studied. Their baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. In total, 101 patients (8.3%) had congestive heart failure, 634 (51.9%) had hypertension, 443 (36.3%) were between 65 and 74 years old, 438 (35.9%) were 75 years old or older, 264 (21.6%) had diabetes, 545 (44.6%) had either prior ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack or prior thromboembolism and 64 (5.2%) had vascular diseases. Overall, 186 patients belonged to the low-risk category, 283 to the intermediate-risk category and 752 to the high-risk category by CHADS2 scores, and 53, 163 and 1005 patients, respectively, by the CHA2DS2-VAS scores. As antithrombotic medications, 873 patients (71.5%) took warfarin, 114 (9.3%) took antiplatelet agents (including 14 patients taking dual antiplatelet agents) and 234 (19.2%) took both (including 19 patients taking warfarin plus dual antiplatelet agents). The median international normalized ratio at entry was 1.95 (interquartile range 1.67–2.30) for warfarin users.

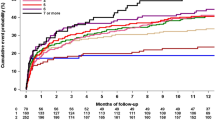

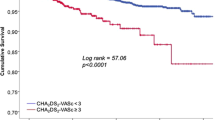

During the median observation period of 19.4 months, 40 ischemic stroke and 39 bleeding events occurred. The annual incidence of both events gradually increased as the CHADS2 risk category became higher, and that of bleeding increased gradually as the CHA2DS2-VASc risk category became higher (Figure 1). After adjustment for antithrombotic medication (model 1), the CHADS2 score was associated (odds ratio 1.76, 95% confidence interval 1.04–3.38 per 1−category increase; 1.35, 1.05–1.74 per 1−point increase) and the CHA2DS2-VASc score tended to be associated (2.20, 0.91–8.46 per 1−category increase; 1.23, 1.01–1.51 per 1−point increase) with ischemia (Table 2). After further adjustment for neoplasm, liver cirrhosis, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking and alcohol consumption (model 2), the CHADS2 score was associated (odds ratio 1.76, 95% confidence interval 1.03–3.38 per 1−category increase; 1.33, 1.03–1.73 per 1−point increase) and the CHA2DS2-VASc tended to be associated (2.18, 0.89–8.43 per 1−category increase; 1.21, 0.99–1.49 per 1−point increase) with ischemia. On the other hand, there were no significant associations of the indices with bleeding after multivariate adjustment.

Finally, associations of components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score with risks of ischemic stroke and bleeding events were also determined (Table 3). Among the components, ‘stroke and thromboembolism’ tended to be associated with ischemic stroke (odds ratio 1.81, 95% confidence interval 0.93–3.66, P=0.073) and ‘75 years or older’ tended to be associated with bleeding events (2.31, 0.96–6.45, P=0.064).

Discussion

The major finding of the present observational study was that bleeding risk increased gradually as the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores increased, although the statistical impact was rather weak as compared with their predictive power for ischemic stroke.

The association of bleeding risk with the CHADS2 score for antiplatelet users and anticoagulant users was determined using the cohort of ACTIVE-W,10 where patients with a score of 0 did not develop major bleeding and those with a score of 1 had a lower incidence of bleeding than those with higher scores. The incidence for intracranial hemorrhage increased as the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores increased in patients treated with either warfarin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban or apixaban.11 In the present study, a similar tendency was seen in Japanese antithrombotic users with AF. A different finding from that of ACTIVE-W was that the annual incidence of major bleeding in patients with the CHADS2/CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 0 exceeded 1% per year; it suggests more careful consideration for antithrombotic use in Japanese patients, a known race for high incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage,12 with the low ischemic risk category than Western patients.

A history of ischemic stroke is a known risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage.6, 13 Hypertension does not only trigger arteriosclerosis and cause ischemic stroke but also triggers arterial damage and cause bleeding.14 Aging is another risk factor for both ischemia and bleeding. Thus, ischemic events and bleeding events seem to share many risk factors. To prevent bleeding complications for antithrombotic users, it is essential to choose appropriate numbers and dosages of antithrombotic agents, as well as to avoid elevation of blood pressure and lower it adequately.7

The strengths of the study include the multicenter, prospective study design with about 2000 patient-years of follow-up. The limitations of the study include the lack of data about bleeding history and genetic factors in the database to calculate HEMORR2HAGES and HAS-BLED. In addition, the small number of patients in the low ischemic risk category, as well as the relatively low incidences of ischemic stroke and bleeding events, might affect the statistical results. Another potential limitation is heterogeneity of the subjects registered in the BAT study. In particular, patients with different antithrombotic medication seemed to have different clinical backgrounds. However, it was statistically inappropriate to analyze patients separately according to the antithrombotic medication due to small sample size. Finally, the INR levels when the events occurred were not fully collectable.

In conclusion, in Japanese antithrombotic users, bleeding risk increased gradually as the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores increased, although the statistical impact was relatively weak. The annual incidence of major bleeding in Japanese antithrombotic users with the CHADS2/CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 0 exceeded 1% per year.

References

Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines-CPG, Document Reviewers. 2012 Focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation–developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2012; 14: 1385–1413.

Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, Waterman AD, Culverhouse R, Rich MW, Radford MJ . Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006; 151: 713–719.

Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY . A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010; 138: 1093–1100.

Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ . Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285: 2864–2870.

Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ . Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010; 137: 263–272.

Toyoda K, Yasaka M, Iwade K, Nagata K, Koretsune Y, Sakamoto T, Uchiyama S, Gotoh J, Nagao T, Yamamoto M, Takahashi JC, Minematsu K . Dual antithrombotic therapy increases severe bleeding events in patients with stroke and cardiovascular disease: a prospective multicenter observational study. Stroke 2008; 39: 1740–1745.

Toyoda K, Yasaka M, Uchiyama S, Nagao T, Gotoh J, Nagata K, Koretsune Y, Sakamoto T, Iwade K, Yamamoto M, Takahashi JC, Minematsu K, Bleeding with Antithrombotic Therapy (BAT) Study Group. Blood pressure levels and bleeding events during antithrombotic therapy: the Bleeding with Antithrombotic Therapy (BAT) Study. Stroke 2010; 41: 1440–1444.

Olesen JB, Lip GY, Hansen ML, Hansen PR, Tolstrup JS, Lindhardsen J, Selmer C, Ahlehoff O, Olsen AM, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C . Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2011; 342: d124.

Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ, MATCH Investigators. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 331–337.

Healey JS, Hart RG, Pogue J, Pfeffer MA, Hohnloser SH, De Caterina R, Flaker G, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ . Risks and benefits of oral anticoagulation compared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation according to stroke risk: the atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for prevention of vascular events (ACTIVE-W). Stroke 2008; 39: 1482–1486.

Banerjee A, Lane DA, Torp-Pedersen C, Lip GY . Net clinical benefit of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus no treatment in a ‘real world’ atrial fibrillation population: a modelling analysis based on a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost 2012; 107: 584–589.

van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ . Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 167–176.

Hart RG, Tonarelli SB, Pearce LA . Avoiding central nervous system bleeding during antithrombotic therapy: recent data and ideas. Stroke 2005; 36: 1588–1593.

Willmot M, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath PM . High blood pressure in acute stroke and subsequent outcome: a systematic review. Hypertension 2004; 43: 18–24.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a Research Grant for Cardiovascular Diseases (15C-1) and Grants-in-Aid (H23-Junkanki-Ippan-010, H24-Junkanki-Ippan-011) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C, 23591288) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Chief Investigator: K Minematsu, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center. Central Trial Office: K Toyoda, A Tokunaga and A Takebayashi, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center; M Yasaka, National Hospital Organization (NHO) Kyushu Medical Center. Investigators and Institutions: S Uchiyama, Tokyo Women’s Medical University School of Medicine; M Yamamoto, Yokohama City Brain and Stroke Center; T Nagao, Tokyo Metropolitan HMTC Ebara Hospital; T Sakamoto, Kumamoto University; M Yasaka, NHO Kyushu Medical Center; K Iwade, NHO Yokohama Medical Center; K Nagata, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels Akita; J Gotoh, NHO Saitama Hospital; Y Koretsune, NHO Osaka Medical Center; K Minematsu and J Takahashi, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center; T Ochi, NHO Kokura Hospital; T Umemoto, NHO Shizuoka Medical Center; T Nakazato, NHO Chiba-East Hospital; M Shimizu, NHO Kobe Medical Center; M Okamoto, NHO Osaka Minami Medical Center; H Shinohara, NHO Zentsuji National Hospital; T Takemura, NHO Nagano Hospital; M Jougasaki and H Matsuoka, NHO Kagoshima Medical Center.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toyoda, K., Yasaka, M., Uchiyama, S. et al. CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores as bleeding risk indices for patients with atrial fibrillation: the Bleeding with Antithrombotic Therapy Study. Hypertens Res 37, 463–466 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.150

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.150

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Beginn der Antikoagulation nach akutem Schlaganfall

InFo Neurologie + Psychiatrie (2021)

-

Anticoagulation Resumption After Stroke from Atrial Fibrillation

Current Atherosclerosis Reports (2019)

-

Resumption of Anticoagulation After Intracranial Hemorrhage

Current Treatment Options in Neurology (2017)

-

Assess bleeding risk with HAS-BLED and assess stroke risk with CHA2DS2-VASc in patients with atrial fibrillation

Hypertension Research (2014)