Abstract

Proper management of hypertension is important for better survival and quality of life of cancer survivors who have hypertension. We aimed to compare hypertension management between cancer survivors and the general population. A nationwide, multicenter, cross-sectional survey was administered to adult cancer patients, currently receiving treatment or follow-up, who had been diagnosed with hypertension. Comparison group was selected from among participants in the health behavior survey of the third Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Self-reported hypertension management was surveyed, including antihypertensive medication adherence, frequency of blood pressure (BP) monitoring and perceived BP control. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between cancer survivorship and each outcome measure. Compared with the general population, cancer survivors were more likely to report full adherence (92.7% vs. 73.0%; adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=3.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.08–5.73), more frequent BP measurement (⩾24 per year: 50.1% vs. 24.7%; aOR=2.51; 95% CI, 1.83–3.46), and very good perceived BP control (60.8% vs. 26.2%; aOR=4.34; 95% CI, 3.13–6.02). Cancer survivors appear to be better with antihypertensive medication adherence and BP monitoring than those without cancer, and as a result, they appear to be under better BP control. However, several methodological limitations of our study prompt further research on this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the survival of cancer patients improves, comorbid conditions are increasing among the major causes of death for many cancer survivors.1 Hypertension is the most common comorbid condition in cancer survivors, with a prevalence of 20–65%.2, 3, 4 Furthermore, it can lead to 30∼50% of excess mortality from stroke and heart disease in cancer survivors,2, 3 as demonstrated in large-cohort studies in Korea3 and the United States.2 Therefore, proper management of hypertension is important for better survival and quality of life of cancer survivors who have hypertension.

Researchers have found that the management of hypertension is affected by various socio-demographic and clinical factors, including age, gender, race, marital status, income level, place of residence, insurance status, comorbid conditions and duration of antihypertensive medication.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 According to the Health Belief Model, certain behavioral factors, such as perceived risk for the disease and perceived benefit of treatment,10, 11, 12 could also affect the management of hypertension. Unlike hypertensive patients without cancer, cancer survivors with hypertension are more likely to consider cancer recurrence, metastasis and a second primary cancer as major health concerns, and usually require more complex care.13 In addition, their personal cancer experiences cause cancer survivors to have different health perceptions and health behaviors.13 Therefore, it is possible that cancer survivors have different practices regarding the management of hypertension compared with people without cancer.

Although some studies have examined the prevalence,4, 14, 15, 16 predictors14, 15, 16 and outcomes2, 3 of hypertension in cancer survivors, little is known about the management perspective of hypertension specific to cancer survivors.17 In the current study, we aimed to compare hypertension management, including antihypertensive medication adherence, frequency of blood pressure (BP) monitoring and perceived BP control between cancer survivors and the general population.

Methods

Study participants

This study was part of a national survey to examine the experiences of cancer survivors in Korea. Data were collected from cancer patients treated at the National Cancer Center and nine regional cancer centers, one in each of the nine provinces of Korea, in 2009. Cancer patients who agreed to participate were interviewed by trained interviewers at their centers of treatment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center in Korea. Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) older than 18 years of age, (2) cancer diagnosis, (3) at least 4 months since diagnosis, (4) currently receiving treatment or follow-up and (5) diagnosis of hypertension at the time of survey.

Comparison group was selected from among participants in the health behavior survey of the third Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). KNHANES is a series of population-based, cross-sectional surveys conducted by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. It uses a stratified multistage sampling design according to geographic area, age and gender group to select a representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized Korean population. All participants signed a written informed consent, and the response rate was 92.7%.18 We included people who were older than 18 years of age, had a diagnosis of hypertension at the time of the survey and who did not have cancer.

Measurements

To compare the hypertension management of cancer patients to the general population, we decided to use the same questions used in the KNHANES for cancer survivors to assess their hypertension management. The outcome measures consisted of three questionnaires in relation to the hypertension management: (1) antihypertensive medication adherence, (2) frequency of BP monitoring and (3) perceived BP control. Patients were asked about antihypertensive medication adherence by the question, ‘Do you regularly take antihypertensive medication for your BP control?’ Response choices were the following: (1) take it regularly at all times, (2) take it occasionally or as needed and (3) do not take it. The frequency of BP monitoring was asked with the question, ‘How often do you measure your BP?’ The responses were collected as number of measurements per day, week, month or year, as appropriate. Perceived BP control was asked with the question, ‘How well do you think your BP is controlled?’ The response choices were (1) very well controlled, (2) well controlled, (3) not well controlled and occasional high BP, (4) not well controlled and frequent high BP and (5) not well controlled at all. For the subsequent analyses, we dichotomized the responses considering the distributions.

Self-reported medication-taking behavior has been reported to be predictive of actual adherence,19, 20 to correlate well with actual BP control21 and even to be linked with cardiovascular outcomes.22 It has been used widely in previous clinical studies regarding adherence,10, 21, 22, 23, 24 although there has been some criticism that it is not very sensitive19 and there is an inconsistent report regarding the concordance with actual behaviors.25 Frequent BP measurement at home may help to improve awareness and concordance, and thus has been shown to be effective in lowering BP.26 Self-reported BP status has been generally reliable and correlated with actual measured data,27 and the perception of BP control has been shown to be related to the intention for improving lifestyle.23

To adjust for potential confounders, we included additional demographic and clinical characteristics identified from previous studies.5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 28, 29 The factors included age, gender, marital status, education, household income, employment status, health insurance status, duration of antihypertensive medication, smoking status and drinking status. Cancer stage was included as a subgroup to assess the impact of competing risks on hypertension management. The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results stage at cancer diagnosis was used,30 but we restaged those with recurrence or metastasis at distant sites, as it was more relevant to our research question.

Statistical analysis

Data for baseline characteristics and hypertension management practices are presented as means±s.d. or numbers and percentages. Both univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to evaluate the relationship between cancer survivorship and each outcome measure. Subgroup analyses were made according to cancer stage. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P-value ≤0.05.

Results

Characteristics of cancer survivors and the general population

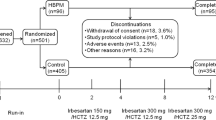

Among the total of 1956 cancer patients who completed the interview process, 385 had a diagnosis of hypertension. Among 7802 participants in KNHANES, 138 were excluded because they reported a cancer diagnosis, and 1124 who had a hypertension diagnosis were included in the study as the comparison group.

The characteristics of cancer survivors and the general population are summarized in Table 1. Cancer survivors were older (65.2 vs. 59.9 years, P<0.001) and had been diagnosed with hypertension earlier (8.4 vs. 6.3 years, P<0.001) than the comparison group. Significant differences existed in gender, education, household income, employment status, health insurance status and health behaviors. Among cancer patients, lung, stomach, colorectal and breast cancer were the most common diagnoses, comprising around two-thirds of the patients, and most survivors had undergone surgery. The mean duration since cancer diagnosis was 1.87 years.

Hypertension management between cancer survivors and the general population

Of the cancer survivors, 92.7% reported taking medication regularly at all times; 73.0% of the non-cancer comparison group reported taking medication regularly at all times. The mean number of BP measurements per year was 98.6 for cancer survivors and 28.8 for the non-cancer comparison group. In addition, 60.8% of the cancer survivors and 26.2% of the non-cancer comparison group perceived their BP to be under very good control (P<0.001 for all parameters; Table 2).

The multiple logistic regression model adjusting for other covariates indicated that, compared with the comparison group, cancer survivors were significantly more likely to report full adherence (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=3.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.08–5.73), BP measurements more than 24 times per year (aOR=2.51; 95% CI, 1.83–3.46) and very good perceived BP control (aOR=4.34; 95% CI, 3.13–6.02). Subgroup analyses by cancer stage showed that patients with in situ or local tumors tended to report full adherence and very good perceived BP control, although there was no statistical significance by trend analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare self-reported hypertension management between cancer survivors and the general population. Our results indicate that compared with the general population, cancer survivors are more likely to regularly take their antihypertensive medication, to more frequently monitor their BP and probably as a consequence, to believe their BP is under very good control.

In general, cancer survivors reported better behaviors related to hypertension management. According to the Health Belief theory, the probability that a person will take a preventive health action is a function of the perceived susceptibility to the disease, its severity and the perceived benefits and barriers related to the recommended preventive action.10 Although it could not be determined whether cancer survivors have a perceived susceptibility specifically to hypertension, they may have an increased perception of vulnerability with respect to their health, and this perceived vulnerability may lead to stricter medication adherence and BP monitoring. In this regard, frequent BP monitoring and good adherence could be a consequence of their increased concern for their health, rather than for the specific purpose of hypertension management. Similar observations can be found with increased cancer screening practices among cancer survivors, even without specific knowledge of the risk for a second primary cancer.13, 31

Cancer survivors were also more likely to perceive their BP as being very well controlled, compared with those in the comparison group. This may be the result of their better adherence and more frequent BP monitoring, both of which lead to better-controlled BP.22, 26 As self-reported BP status is generally reliable and correlated with actual measured data,27 it can be assumed that hypertensive cancer survivors are usually in better control of their BP than are hypertensive patients without cancer.

Although not statistically significant, there were noticeable trends of less strict adherence and poorer perceived BP control among cancer survivors with more advanced stage cancer. People with advanced cancer may perceive their prognosis as poor and thus may be more likely to ignore the benefits of hypertension management. This would be consistent with the Health Belief model, which explains medication adherence with long-term antihypertensive therapy,10 in that a smaller perceived benefit leads to less favorable behavior. Complexity of care for the management of advanced cancer might be another potential reason for poorer compliance.32

The present study should be interpreted with full knowledge of its limitations. First, the main limitations are those common to studies with a survey data set. As actual measurements of BP were not performed, persons who might not have been hypertensive at the time of the survey might have been included, while those who were not aware of their high BP might have been missed. However, it is impractical to confirm BP in this kind of design, as the diagnosis of hypertension and judgment of adequacy of BP control require multiple sequential BP measurements. Many large-scale studies have also used self-reporting to determine the occurrence of hypertension.

Second, the survey questions on main outcome measures limited deeper investigation and were not well validated. There are some validated measures for medication adherence, such as the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.33 Yet, in this study we had to use these specific questionnaires from KHANES to compare the hypertension management of cancer patients to the general population. Moreover, in previous studies other various question formats have been used for self-reported antihypertensive adherence,20, 22 and we are not aware of any validated self-reporting measures for BP monitoring behavior or perceived BP control.23

A third limitation is the potential for selection bias. The cancer survivors who participated in this study were recruited from a hospital sample, whereas the controls were recruited from the community. However, considering that most cancer survivors regularly visit a hospital for treatment or routine surveillance, the effect of this selection may not be significant. Indeed, an additional analysis of hypertensive cancer survivors in KNHANES revealed similar results (for example, aOR=3.81; 95% CI, 0.90–16.18 for antihypertensive full adherence). However, we did not use the cancer survivor sample from the KNHANES data set for this comparison because of its limited sample size (n=37) and lack of stage data.

Fourth, there are concerns about the accuracy of self-reports. Our previous study showed similar antihypertensive medication adherence between cancer survivors and the comparison group (84.0% vs. 85.6%) using the claim data set.17 The agreement between self-reported adherence and refill adherence is reported to be only poor to fair,9, 22 and it has been suggested that these two methods reflect different dimensions of medication-taking behavior.34 Other potential explanations would be increased awareness of non-cancer care among cancer survivors between the study period (2002 vs. 2009),35, 36 and insufficient adjustment of potential confounders, such as education, employment status and smoking, in the previous study.17 Given the lack of a gold standard, the discrepancy between our two methodologically different studies underscore the need to conduct further investigations. Concurrent measurements of actual adherence and BP may be needed to examine whether cancer survivors are overestimating their adherence or BP control.37

Lastly, our study did not consider the physician–patient interaction, which could be a significant source of actual and perceived hypertension management.10, 38 The situation that cancer survivors face in the treatment of hypertension may be quite different from that of usual hypertensive patients without cancer. It is important to understand whether cancer survivors obtain prescriptions for their hypertension from oncologists or from primary care physicians, and how much they are informed of their BP status or encouraged to be fully adherent to medication by their physician.39 Further study is warranted to investigate how patient–physician interaction factors affect the hypertension management and perception of cancer survivors.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, this study is one of the few studies to evaluate hypertension management issues in cancer survivors. Cancer survivors appear to be better with antihypertensive medication adherence and BP monitoring, compared with hypertensive patients without cancer. As a result, they also appear to be under better BP control. There were trends of less strict adherence and poorer perceived BP control among cancer survivors with more advanced stage cancer. Our findings suggest the role of complexity of care and health perception in the management of hypertension in cancer survivors. However, several methodological limitations of our study prompt further research on this issue, especially with regard to the accuracy of self-reporting and patient–physician interactions in this specific population.

References

Shin DW, Ahn E, Kim H, Park S, Kim YA, Yun YH . Non-cancer mortality among long-term survivors of adult cancer in Korea: national cancer registry study. Cancer Causes Control 2010; 21: 919–929.

Braithwaite D, Tammemagi CM, Moore DH, Ozanne EM, Hiatt RA, Belkora J, West DW, Satariano WA, Liebman M, Esserman L . Hypertension is an independent predictor of survival disparity between African-American and white breast cancer patients. Int J cancer 2009; 124: 1213–1219.

Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH . Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 5017–5024.

Shin DW, Nam JH, Kwon YC, Park SY, Bae DS, Park CT, Cho CH, Lee JM, Park SM, Yun YH . Comorbidity in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general female population. Oncology 2008; 74: 207–215.

Steiner JF, Prochazka AV . The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J C Epidemiol 1997; 50: 105–116.

Rudd P . Clinicians and patients with hypertension: unsettled issues about compliance. Am Heart J 1995; 130: 572–579.

Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Gibson ES, Hackett BC, Taylor DW, Roberts RS, Johnson AL . Randomised clinical trial of strategies for improving medication compliance in primary hypertension. Lancet 1975; 1: 1205–1207.

Eraker SA, Kirscht JP, Becker MH . Understanding and improving patient compliance. Ann Intern Med 1984; 100: 258–268.

Morris AB, Li J, Kroenke K, Bruner-England TE, Young JM, Murray MD . Factors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Pharmacotherapy 2006; 26: 483–492.

Nelson EC, Stason WB, Neutra RR, Solomon HS, McArdle PJ . Impact of patient perceptions on compliance with treatment for hypertension. Med care 1978; 16: 893–906.

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Canning C, Platt R . A cohort study of possible risk factors for over-reporting of antihypertensive adherence. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2001; 1: 6.

Dijkstra A, Okken V, Niemeijer M, Cleophas T . Determinants of perceived severity of hypertension and drug-compliance in hypertensive patients. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 2008; 8: 179–184.

Shin DW, Baik YJ, Kim YW, Oh JH, Chung KW, Kim SW, Lee WC, Yun YH, Cho J . Knowledge, attitudes, and practice on second primary cancer screening among cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 85: 74–78.

Haddy TB, Mosher RB, Reaman GH . Hypertension and prehypertension in long-term survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007; 49: 79–83.

Baker KS, Ness KK, Steinberger J, Carter A, Francisco L, Burns LJ, Sklar C, Forman S, Weisdorf D, Gurney JG, Bhatia S . Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular events in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplantation survivor study. Blood 2007; 109: 1765–1772.

Meacham LR, Chow EJ, Ness KK, Kamdar KY, Chen Y, Yasui Y, Oeffinger KC, Sklar CA, Robison LL, Mertens AC . Cardiovascular risk factors in adult survivors of pediatric cancer--a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 170–181.

Shin DW, Park JH, Park JH, Park EC, Kim SY, Kim SG, Choi JY . Antihypertensive medication adherence in cancer survivors and its affecting factors: results of a Korean population-based study. Support Care Cancer 2010; 19: 211–220.

The Ministry of Health Welfare, and Famiily Affairs & Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The Guideline for the Usage of KNHANES III Original Data. Seoul, Korea. 2007.

Inui TS, Carter WB, Pecoraro RE . Screening for noncompliance among patients with hypertension: is self-report the best available measure? Medcare 1981; 19: 1061–1064.

Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hay AD, Montgomery A, Peters TJ . Adherence to antihypertensive medication assessed by self-report was associated with electronic monitoring compliance. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 650–651.

Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM . Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med care 1986; 24: 67–74.

Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ryan P, Willson K, Yelland L . Self-reported adherence with medication and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2). Med J Aust 2006; 185: 487–489.

Gee ME, Campbell NR, Bancej CM, Robitaille C, Bienek A, Joffres MR, Walker RL, Kaczorowski J, Dai S . Perception of uncontrolled blood pressure and behaviours to improve blood pressure: findings from the 2009 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada. J Hum Hypertens 2012; 26: 188–195.

Holt EW, Muntner P, Joyce CJ, Webber L, Krousel-Wood MA . Health-related quality of life and antihypertensive medication adherence among older adults. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 481–487.

Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, Battegay E . Patients' self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 2037–2043.

Cappuccio FP, Kerry SM, Forbes L, Donald A . Blood pressure control by home monitoring: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2004; 329: 145.

Johnson KA, Partsch DJ, Rippole LL, McVey DM . Reliability of self-reported blood pressure measurements. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 2689–2693.

Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J . Compliance with antihypertensive therapy among elderly Medicaid enrollees: the roles of age, gender, and race. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 1805–1808.

Shea S, Misra D, Ehrlich MH, Field L, Francis CK . Correlates of nonadherence to hypertension treatment in an inner-city minority population. Am J Public Health 1992; 82: 1607–1612.

Young JL, Roffers SD, Ries LAG, Fritz AG, Hurlbut AA (eds). SEER Summary Staging Manual—2000: Codes and Coding Instructions, NIH Pub. No. 01-4969 National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2001.

Cho J, Guallar E, Hsu YJ, Shin DW, Lee WC . A comparison of cancer screening practices in cancer survivors and in the general population: the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES) 2001-2007. Cancer Causes Control 2010; 21: 2203–2212.

Wang PS, Avorn J, Brookhart MA, Mogun H, Schneeweiss S, Fischer MA, Glynn RJ . Effects of noncardiovascular comorbidities on antihypertensive use in elderly hypertensives. Hypertension 2005; 46: 273–279.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ . Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens 2008; 10: 348–354.

Thorpe CT, Bryson CL, Maciejewski ML, Bosworth HB . Medication acquisition and self-reported adherence in veterans with hypertension. Med care 2009; 47: 474–481.

Earle CC, Neville BA . Underuse of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer 2004; 101: 1712–1719.

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS . Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 5117–5124.

Horwitz SM, Prados-Torres A, Singer B, Bruce ML . The influence of psychological and social factors on accuracy of self-reported blood pressure. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 411–418.

Roumie CL, Greevy R, Wallston KA, Elasy TA, Kaltenbach L, Kotter K, Dittus RS, Speroff T . Patient centered primary care is associated with patient hypertension medication adherence. J Behav Med 2011; 34: 244–253.

Inui TS, Yourtee EL, Williamson JW . Improved outcomes in hypertension after physician tutorials. A controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84: 646–651.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Cancer Center (Grant No. 1210150), a grant of the National R&D Program for Cancer Control (grant 1020010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wook Shin, D., Young Kim, S., Cho, J. et al. Comparison of hypertension management between cancer survivors and the general public. Hypertens Res 35, 935–939 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.54

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.54

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Adherence to cardiovascular disease risk factor medications among patients with cancer: a systematic review

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2023)

-

Chronic arterial hypertension impedes glioma growth: a multiparametric MRI study in the rat

Hypertension Research (2015)

-

Factors influencing medication adherence and hypertension management revisited: recent insights from cancer survivors

Hypertension Research (2012)