Abstract

Hypertension and smoking are major causes of disability and death, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, where there is a high prevalence of a combination of these two risk factors. We attempted to measure the medical expenditures of a Japanese male population with hypertension and/or a smoking habit over a 10-year period of follow-up. A cohort study was conducted that investigated the medical expenditures due to a smoking habit and/or hypertension during the decade of the 1990s using existing data on physical status and medical expenditures. The participants included 1708 community-dwelling Japanese men, aged 40–69 years, who were classified into the following four categories: ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’, ‘smoking habit alone’, ‘hypertension alone’ or ‘both smoking habit and hypertension.’ Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ⩾140 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure of ⩾90 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive medications. In the study cohort, 24.9% had both a smoking habit and hypertension. During the 10-year follow-up period, participants with a smoking habit alone (18 444 Japanese yen per month), those with hypertension alone (21 252 yen per month) and those with both a smoking habit and hypertension (31 037 yen per month) had increased personal medical expenditures compared with those without a smoking habit and hypertension (17 418 yen per month). Similar differences were observed even after adjustment for other confounding factors (P<0.01). Japanese men with both a smoking habit and hypertension incurred higher medical expenditures compared with those without a smoking habit, hypertension or their combination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Elevated blood pressure is the leading cause of death, as well as a major cause of disability in the world.1, 2 Approximately 13.5% of all deaths and 6.0% of all disability-adjusted life years among those aged ⩾30 years are attributable to high blood pressure with systolic blood pressure of >115 mm Hg.3 This is because of the strong effect of hypertension on the development of cardiovascular disease, including coronary heart disease and stroke.4, 5, 6, 7 Hypertension is a major contributor to cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region.3 Furthermore, cigarette smoking, which leads to cardiovascular disease as well as cancer and respiratory disease,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 is also a major health burden in the Asia-Pacific region because of its popularity among men;13 nearly two-thirds of the world’s smokers live in 10 countries, and most of them are in that region.14 Thus, both hypertension and a smoking habit might be more important determinants of human health than other risk factors in the Asia-Pacific region.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 For example, in Japan, hypertension and a smoking habit contribute to 20.8 and 20.5% of deaths among men, respectively, which is much greater than the mortality because of hypercholesterolemia (4.5%) or diabetes (5.0%).15 In addition, 20–30% of Japanese men are estimated to have both hypertension and a smoking habit simultaneously,16, 23 and the risk of cardiovascular disease is higher in these individuals than in those with just one or neither of these two risk factors.6, 7, 11, 12, 16

The effect of hypertension and smoking should be considered from the viewpoint of medical expenditures, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region where there is a high prevalence of individuals with both of these two risk factors. However, the majority of previous epidemiological studies have only reported the association between a single risk factor and medical expenditures.24, 25, 26, 27 We hypothesized that hypertensive individuals with a smoking habit would incur higher future medical expenditures, especially in-patient expenditures, than those with just one or neither of these two risk factors because of a high incidence of cardiovascular and other serious diseases. To test this hypothesis, we attempted to measure the medical expenditures of individuals with hypertension and/or a smoking habit over a 10-year period in a community-based, male Japanese population.

Methods

Medical expenditures

In Japan, many medical services are provided by the public medical insurance system,28, 29, 30 which requires the enrollment of all Japanese residents (‘health-insurance-for-all’). During the period when data were collected (from 1990 to 2001), public medical insurance consisted of two insurance systems. The eligibility for each insurance system was as follows: the first system, named Social Insurance, was for employees and their dependants and covered approximately two-thirds of the overall Japanese population; the other system, named National Health Insurance (NHI), was for those not covered by Social Insurance, for example, self-employed individuals such as farmers and fishermen, as well as retirees and their dependants, and covered the remaining one-third of the population. Prices were strictly controlled by a fee schedule set by the National Government and were determined on a ‘fee-for-service’ basis. The fee schedule was the same regardless of the insurance system. Furthermore, the same fee schedule applied to all the clinics and hospitals given approval to provide medical services under the public medical insurance system. However, some medical services including health check-ups for asymptomatic individuals and inoculations were not covered by medical insurance. The fee for these services was recorded in an insurance claim history file.

In this study, we used the insurance claim history files to obtain information on medical expenditures. Therefore, the medical expenditures in this study were confined to the range of the fee schedule used in the public medical insurance system in Japan. Total medical expenditures were divided into outpatient and in-patient medical expenditures.

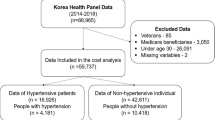

Study design and participants

The present cohort comprised 4535 Japanese beneficiaries of NHI, the insurance system for self-employed individuals. The details of the present cohort have been reported previously.25, 31, 32, 33 In brief, the study participants, aged 40–69 years, lived in seven rural towns and a village in Shiga Prefecture, West Japan, and had a voluntary baseline survey in 1989–1991. In 1990, the study area had 82 155 residents, including 31 564 individuals aged 40–69 years, of whom 11 900 were NHI beneficiaries.34 Therefore, the participants in this study represented approximately 38% of all NHI beneficiaries aged 40–69 years living in this area. The analysis was conducted only for men, because the prevalence of smokers is quite low among Japanese women;8, 9, 10, 16, 23, 35 our data showed that current smokers and former smokers accounted for 3.4% (n=87) and 0.5% (n=14), respectively, of 2596 female participants. Of the 1939 male participants, 231 were excluded because they were former smokers (n=229) or there was no information on smoking habit at the baseline survey (n=2). We excluded former smokers from the analysis because we wanted an exact measure of medical expenditures related to smoking at baseline. The remaining 1708 participants were included in the analysis. Monthly NHI claim history files of the Shiga NHI Organizations were linked with the baseline survey data files at the organizations. To protect the participants’ privacy, their names were deleted from the linked data at the organizations. Therefore, the data were analyzed without knowledge of the participants’ identity. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Shiga University of Medical Science for ethical issues (no. 16–15).

Data collection

The baseline survey was performed during the period 1989–1991 using standardized methods in accordance with the Manual for Health Check-ups under the Medical Service Law for the Aged, issued by the Japan Public Health Association in 1987.36 Blood pressures were measured by well-trained public health nurses in the right arm in the sitting position using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after the participants had rested for at least 5 min. The use of antihypertensive medications and smoking habit were obtained from interviews conducted by well-trained public health nurses and medical doctors. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ⩾140 mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure of ⩾90 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive medications. On the basis of this information, all eligible male participants were classified into the following four categories: ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’, ‘smoking habit alone’, ‘hypertension alone’ or ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’. A drinking habit and a history of diabetes were also evaluated by the interviews. Body height and weight were measured and body mass index was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of body height (m2). Serum total cholesterol levels were measured by an enzymatic method.

We calculated medical expenditures per person in each of the four categories after a 10-year follow-up period. Information on medical expenditures for each participant and information on participants who withdrew from the NHI or those who died were obtained from the monthly NHI claim history files, beginning in April of the year after their initial health check-up and continuing until March 2001. Medical expenditures were expressed in Japanese yen, US dollars and euros (100 Japanese yen=1.08 US dollars or 0.76 euros, at the foreign exchange rate on 1 September 2009). Data on medical expenditures for each participant differed depending upon the period of subscription to the NHI. The medical expenditures for each participant were therefore divided by the period of subscription and expressed as expenditures per month of follow-up. If a beneficiary withdrew from the NHI or died, follow-up was terminated at that point. Follow-up was restarted for beneficiaries who withdrew and then re-enrolled in the NHI. Reasons for withdrawal from the NHI included moving to regions outside of Shiga Prefecture or transfer to the other insurance system.

Data analysis

Because the distribution of real medical expenditures was positively skewed, the data were logarithmically transformed to normalize the distribution and the results were expressed as geometric means. For participants with expenditures of 0 yen per month, the logarithmic transformations were performed by replacing 0 yen with 1 yen. There were four participants with total medical expenditures of 0 yen and five participants with outpatient medical expenditures of 0 yen. For comparison of total and outpatient medical expenditures per person in each category, we performed an analysis of covariance with the Bonferroni correction to adjust the P-value for multiple post hoc comparisons. The analysis of covariance incorporated the following variables as covariates: age (40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64 or 65–69 years old, using five dummy variables with 40–44 as a reference), body mass index, drinking habit (non-, current occasional or current daily drinker, using two dummy variables with non-drinkers as a reference), serum total cholesterol and a history of diabetes. Because 896 participants (52.5%) had in-patient medical expenditures of 0 yen, logarithmic transformations were not performed, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare in-patient medical expenditures among the four categories. A similar analysis was repeated after excluding participants who were taking antihypertensive medications at baseline.

In addition, to clarify whether medical expenditures associated with smoking and/or hypertension increase over time because of the occurrence of cardiovascular and other serious diseases, we calculated medical expenditures per person in each of the four categories for the overall follow-up period of 10 years and also stratified expenditures by the follow-up period (the first 5 years and the latter 5 years), using subgroups in which every participant was followed for >5 years.

Finally, we examined excess medical expenditures attributable to hypertension and/or a smoking habit in the study population using the arithmetic means of total medical costs in each category. The excess medical expenditures attributable to hypertension and/or a smoking habit were calculated as follows: (total medical expenditures in the ‘smoking habit alone’, ‘hypertension alone’, and ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’ category–total medical expenditures in the ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’ category) × number of participants in the ‘smoking habit alone’, ‘hypertension alone’ and ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’ category.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 14.0J for Windows (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The P-values were two sided and P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Current smokers accounted for 68.1% of the 1708 male study participants, whereas hypertensive individuals accounted for 36.9% of the cohort. Table 1 summarizes the baseline risk characteristics of the male participants, grouped according to their smoking habit and hypertension status. Of the study population, 24.9% had both a smoking habit and hypertension, whereas 43.2% had smoking habit alone and 11.9% had hypertension alone. The ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’ group had the highest mean age. Only approximately 1% of the participants in each category had a history of cardiovascular disease, and no remarkable differences were observed among the four categories.

Total person-years were 15 508 and the mean follow-up time was 9.1 years. As shown in Table 2, during the 10-year follow-up period, total medical expenditures per person in the ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’ category (31 037 Japanese yen per month) tended to be higher than in the ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’ category (17 418 yen per month), in the ‘smoking habit alone’ category (18 444 yen per month) and in the ‘hypertension alone’ category (21 252 yen per month). For the multivariate-adjusted geometric means of total medical expenditures, the differences among the four categories were statistically significant (P<0.01). Similar statistically significant differences were also observed in outpatient medical expenditures (P<0.01). In addition, in-patient medical expenditures showed statistically significant differences among the four categories (P<0.01).

Subgroup analysis, in which participants taking antihypertensive medications at baseline were excluded (n=80), showed a broadly similar pattern; total medical expenditures per person were 19 084 yen per month for the ‘hypertension alone’ category (n=172) (outpatient, 11 108 yen; and in-patient, 7976 yen) and 31 263 yen per month for the ‘both smoking habit and hypertension’ category (n=378) (outpatient, 13 658 yen; and in-patient, 17 604 yen; data not shown in the table). However, the difference in medical expenditures, especially for outpatients, between the ‘hypertension alone’ category and the ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’ category was attenuated.

Table 3 shows medical expenditures per person grouped by smoking habit and hypertension status for the overall follow-up period of 10 years and also stratified by the follow-up period, which was derived from subgroups in which all participants had >5 years of follow-up (n=1491). The differences in medical expenditures, especially in-patient expenditures, among the four categories were much greater in the latter 5 years of follow-up than in the first 5 years.

Compared with the ‘neither smoking habit nor hypertension’ category, the excess medical expenditures attributable to a smoking habit alone were estimated to be 757 188 yen per month, and were calculated as follows: (18 444 yen–17 418 yen) × 738 participants with a smoking habit alone. Accordingly, the excess medical expenditures attributable to a smoking habit alone represented 2.0% of the total medical expenditures for the 1708 participants (37 090 403 yen), and were calculated as follows: 757 188 yen/37 090 403 yen. Using similar methods, the excess medical expenditures attributable to hypertension alone and both a smoking habit and hypertension were estimated to be 782 136 yen and 5 801 694 yen, respectively, which represented 2.1 and 15.6% of the total medical expenditures for the study cohort.

Discussion

We carried out a 10-year follow-up study between 1990 and 2001 and showed that Japanese men with a smoking habit alone, hypertension alone or both a smoking habit and hypertension had increased personal medical expenditures compared with those without a smoking habit and hypertension. The coexistence of these two risk factors further increased medical expenditures in comparison with the existence of just one of these two risk factors. The increments in the expenditures associated with both or just one of these two risk factors were prominent in the latter period of follow-up. The sum of excess medical expenditures attributable to hypertension and/or a smoking habit represented approximately 20% of the total medical expenditures of the study cohort. An important strength of our study was that the participants consisted of community-based individuals who were beneficiaries of one of the public medical insurance systems on the basis of ‘health-insurance-for-all’ in Japan. Therefore, our data can probably be generalized to the Japanese male population. An additional strength of our study was that the 10-year follow-up period was long enough to provide an accurate evaluation of medical expenditures associated with serious conditions caused by smoking and hypertension. This allowed the calculation of medical expenditures stratified by the follow-up period.

Our data showed that hypertension alone or a smoking habit alone increased total medical expenditures by 3834 yen and 1026 yen, respectively, which represented a 22 and 6% increment compared with the expenditures of individuals without either risk factor. Medical expenditures in the participants with hypertension alone tended to be higher than in those with a smoking habit alone. This may be reasonable, because the treatment of hypertension usually requires antihypertensive medications, and this directly increases medical expenditures, especially for outpatients. The results from our subgroup analysis after excluding participants with antihypertensive medications at baseline support this explanation. At the time of our study, any medical services for smoking cessation, including nicotine replacement therapy, were not provided by the public medical insurance system in Japan. However, the analysis stratified by the follow-up period showed a further increment in expenditures, especially in-patient expenditures, of participants with smoking alone in the latter 5 years of follow-up. These results suggest that smoking increases medical expenditures later because of the occurrence of serious diseases. A similar explanation may be applicable to increased medical expenditures of participants with hypertension alone in the later period, which may be because of the use of antihypertensive medications as well as the occurrence of cardiovascular disease. However, we could not identify the particular disease or event that directly increased medical expenditures among participants with either hypertension or smoking.

The coexistence of a smoking habit and hypertension was identified in approximately 25% of the study cohort and increased total medical expenditures by 13 619 yen. This represented a 78% increment compared with the expenditures of individuals with neither risk factor. NIPPON DATA8016 and the Hisayama study11 reported that Japanese who had both hypertension and a smoking habit were at increased risk of cardiovascular disease compared with those who had either risk factor alone or neither risk factor. These previous reports provide one possible explanation for our findings of increased medical expenditures of hypertensives with a smoking habit compared with the other three categories. Alternatively, the effect of smoking on cancer and respiratory disease8, 9 might have contributed to the increased medical expenditures among hypertensives with a smoking habit. Our data on the time-related changes of medical expenditures during the follow-up period support these possible explanations, as there was a 232% increment in future expenditures of individuals with both risk factors compared with individuals with neither risk factor.

The mean level of blood pressure is higher in Japan than in Western countries,17, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 despite a substantial decline in blood pressure during the past four decades.42 In addition, the prevalence of smoking among Japanese men remains much higher compared with men in the West,8, 9, 10, 17, 35, 37, 41, 43 although there has been a trend for a decline in smoking.42 As a result, approximately 70–80% of Japanese men have hypertension and/or a smoking habit,16, 23 which would directly contribute to as much as 20% of the entire medical expenditures in this population. Individuals with the coexistence of both these two risk factors comprise approximately 20–30% of the Japanese male population.16, 23 It should be noted that the combination of hypertension and smoking would contribute to approximately 15% of total medical expenditures, not only because of the substantially high value of medical expenditures but also because of the high prevalence of individuals with the coexistence of both risk factors. As the relative importance of hypertension and smoking on human health is likely to be similar among Japan and other Asia-Pacific countries such as China and Korea,17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 a broadly similar pattern of increased medical expenditure may be observed in these countries as well.

This study has several limitations. First, although the participants were selected from a community-based population whose health status was relatively typical of the overall Japanese population,28 the participants were limited to NHI beneficiaries belonging to self-employed occupational groups in one area of Shiga prefecture. The socio-economic status and lifestyle of these beneficiaries may have had an effect on their health. In addition, the study participants may have been concerned about their heath status, because they voluntarily underwent the survey. Moreover, no information on a history of serious disease other than cardiovascular diseases was available at baseline. However, the study participants consisted of healthy community-dwelling individuals who participated in the baseline survey without the need of assistance. We therefore believe that most of the participants were free of serious disease at baseline, as a history of cardiovascular disease was identified at baseline in only 0.7% of the participants. Second, the public medical insurance system in Japan differs from that in other countries. Therefore, absolute values of medical expenditures estimated in this study should not be directly comparable to other populations, and our results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other populations. Third, blood pressure was measured only once in each participant, and classification of participants based on this single measurement may have overestimated the prevalence of hypertension. This misclassification may consequently have led to the underestimation of differences in medical expenditures between the hypertensive and non-hypertensive groups. In addition, we had no serial data on smoking habit and hypertension after the baseline survey. Despite the lack of serial data, we believe that our results, based on a single baseline survey and 10-year follow-up, support our conclusion that hypertensive individuals with a smoking habit incur higher medical expenditures in the future. Fourth, our analysis did not account for the severity of hypertension or the amount of tobacco smoking because the number of eligible participants was not large enough to stratify hypertension and smoking status. Finally, the details of the medical diagnoses, medical treatment status (for example, prescriptions), clinical condition and cause of mortality were not available in this study. Thus, further studies are needed to clarify the effect of these variables. However, our subgroup analysis provided important evidence that antihypertensive medications significantly increase medical expenditures, especially outpatient expenditures.

In conclusion, hypertensive individuals with a smoking habit incur higher medical expenditures in the Japanese male population. Attention should be paid to such individuals, especially in countries where both hypertension and a smoking habit are prevalent. To reduce the economic burden on the health-care system because of hypertension and smoking, efforts should be made to prevent and treat hypertension and to encourage individuals not to smoke, especially before the occurrence of serious diseases that increase medical expenditures.

References

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ . Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006; 367: 1747–1757.

World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002. Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2002.

Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A . Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet 2008; 371: 1513–1518.

MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J . Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990; 335: 765–774.

Nippon Data 80 Research Group. Impact of elevated blood pressure on mortality from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, heart disease and stroke among Japanese: 14 year follow-up of randomly selected population from Japanese—Nippon data 80. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17: 851–857.

Khalili P, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Berglund G . Smoking as a modifier of the systolic blood pressure-induced risk of cardiovascular events and mortality: a population-based prospective study of middle-aged men. J Hypertens 2002; 20: 1759–1764.

Shaper AG, Phillips AN, Pocock SJ, Walker M, Macfarlane PW . Risk factors for stroke in middle aged British men. BMJ 1991; 302: 1111–1115.

Nakamura K, Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Woodward M . The hazards and benefits associated with smoking and smoking cessation in Asia: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Tob Control 2009; 18: 345–353.

Katanoda K, Marugame T, Saika K, Satoh H, Tajima K, Suzuki T, Tamakoshi A, Tsugane S, Sobue T . Population attributable fraction of mortality associated with tobacco smoking in Japan: a pooled analysis of three large-scale cohort studies. J Epidemiol 2008; 18: 251–264.

Ueshima H, Choudhury SR, Okayama A, Hayakawa T, Kita Y, Kadowaki T, Okamura T, Minowa M, Iimura O . Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke death in Japan: NIPPON DATA80. Stroke 2004; 35: 1836–1841.

Kiyohara Y, Ueda K, Fujishima M . Smoking and cardiovascular disease in the general population in Japan. J Hypertens 1990; 8 (Suppl 5): S9–15.

Janzon E, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Engstrom G . Tobacco and myocardial infarction in middle-aged women: a study of factors modifying the risk. J Intern Med 2004; 256: 111–118.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD . Regional, disease specific patterns of smoking-attributable mortality in 2000. Tob Control 2004; 13: 388–395.

Chan M . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008: Fresh and Alive. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2008.

Yamamoto T, Nakamura Y, Hozawa A, Okamura T, Kadowaki T, Hayakawa T, Murakami Y, Kita Y, Okayama A, Abbott RD, Ueshima H . Low-risk profile for cardiovascular disease and mortality in Japanese. Circ J 2008; 72: 545–550.

Hozawa A, Okamura T, Murakami Y, Kadowaki T, Nakamura K, Hayakawa T, Kita Y, Nakamura Y, Abbott RD, Okayama A, Ueshima H . Joint impact of smoking and hypertension on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in Japan: NIPPON DATA80, a 19-year follow-up. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 1169–1175.

Zhang XF, Attia J, D’Este C, Yu XH . Prevalence and magnitude of classical risk factors for stroke in a cohort of 5092 Chinese steelworkers over 13.5 years of follow-up. Stroke 2004; 35: 1052–1056.

Jee SH, Suh I, Kim IS, Appel LJ . Smoking and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in men with low levels of serum cholesterol: the Korea Medical Insurance Corporation Study. JAMA 1999; 282: 2149–2155.

Martiniuk AL, Lee CM, Lawes CM, Ueshima H, Suh I, Lam TH, Gu D, Feigin V, Jamrozik K, Ohkubo T, Woodward M . Hypertension: its prevalence and population-attributable fraction for mortality from cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 73–79.

Martiniuk AL, Lee CM, Lam TH, Huxley R, Suh I, Jamrozik K, Gu DF, Woodward M . The fraction of ischaemic heart disease and stroke attributable to smoking in the WHO Western Pacific and South-East Asian regions. Tob Control 2006; 15: 181–188.

Woodward M, Martiniuk A, Ying Lee CM, Lam TH, Vanderhoorn S, Ueshima H, Fang X, Kim HC, Rodgers A, Patel A, Jamrozik K, Huxley R . Elevated total cholesterol: its prevalence and population attributable fraction for mortality from coronary heart disease and ischaemic stroke in the Asia-Pacific region. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008; 15: 397–401.

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and population attributable fractions for coronary heart disease and stroke mortality in the WHO South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007; 16: 187–192.

Japan Heart Foundation. The Fifth National Survey on Circulatory Disorders. Chuohoki Publishers: Tokyo, 2003 (in Japanese).

Hebel JR, McCarter RJ, Sexton M . Health care costs for employed hypertensives. Med Care 1990; 28: 446–457.

Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, Hayakawa T, Kadowaki T, Okayama A, Ueshima H . Impact of hypertension on medical economics: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. Hypertens Res 2005; 28: 859–864.

Hodgson TA . Cigarette smoking and lifetime medical expenditures. Milbank Q 1992; 70: 81–125.

Izumi Y, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, Kuwahara A, Nishino Y, Hisamichi S . Impact of smoking habit on medical care use and its costs: a prospective observation of National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 616–623.

Health and Welfare Statistics Association. 2004 Kokumin Eisei no Doko (Trend for National Health and Hygiene, Japan). Health and Welfare Statistics Association: Tokyo, 2004. (in Japanese).

Health and Welfare Statistics Association. 2004 Hoken to Nenkin no Doko (Trend for Insurance and Pension, Japan). Health and Welfare Statistics Association: Tokyo, 2004. (in Japanese).

Ito M . Health insurance systems in Japan: a neurosurgeon’s view. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004; 44: 617–628.

Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, Hayakawa T, Okayama A, Ueshima H . Medical costs of patients with hypertension and/or diabetes: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 2305–2309.

Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, Hayakawa T, Okayama A, Ueshima H . Medical costs of obese Japanese: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. Eur J Public Health 2007; 17: 424–429.

Okamura T, Nakamura K, Kanda H, Hayakawa T, Hozawa A, Murakami Y, Kadowaki T, Kita Y, Okayama A, Ueshima H . of combined cardiovascular risk factors on individual and population medical expenditures: a 10-year cohort study of national health insurance in a Japanese population. Circ J 2007; 71: 807–813.

Shiga Prefectural Government. Heisei 2-nendo Shiga-ken Tokeisyo (1990 Data of Shiga Prefecture). Shiga Prefectural Government: Otsu, 1992 (in Japanese).

Tamaki J, Ueshima H, Hayakawa T, Choudhury SR, Kodama K, Kita Y, Okayama A . Effect of conventional risk factors for excess cardiovascular death in men: NIPPON DATA80. Circ J 2006; 70: 370–375.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare. Manual for Health Check-Ups under Medical Service Law for the Aged. Japan Public Health Association: Tokyo, 1987 (in Japanese).

Kuulasmaa K, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Dobson A, Fortmann S, Sans S, Tolonen H, Evans A, Ferrario M, Tuomilehto J . Estimation of contribution of changes in classic risk factors to trends in coronary-event rates across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet 2000; 355: 675–687.

INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ 1988; 297: 319–328.

Baba S, Pan WH, Ueshima H, Ozawa H, Komachi Y, Stamler R, Ruth K, Stamler J . Blood pressure levels, related factors, and hypertension control status of Japanese and Americans. J Hum Hypertens 1991; 5: 317–332.

Elliott P, Stamler J, Dyer AR, Appel L, Dennis B, Kesteloot H, Ueshima H, Okayama A, Chan Q, Garside DB, Zhou B . Association between protein intake and blood pressure: the INTERMAP Study. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 79–87.

Sekikawa A, Ueshima H, Zaky WR, Kadowaki T, Edmundowicz D, Okamura T, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Nakamura Y, Egawa K, Kanda H, Kashiwagi A, Kita Y, Maegawa H, Mitsunami K, Murata K, Nishio Y, Tamaki S, Ueno Y, Kuller LH . Much lower prevalence of coronary calcium detected by electron-beam computed tomography among men aged 40–49 in Japan than in the US, despite a less favorable profile of major risk factors. Int J Epidemiol 2005; 34: 173–179.

Ueshima H . Explanation for the Japanese paradox: prevention of increase in coronary heart disease and reduction in stroke. J Atheroscler Thromb 2007; 14: 278–286.

Stamler J, Elliott P, Dennis B, Dyer AR, Kesteloot H, Liu K, Ueshima H, Zhou BF . INTERMAP: background, aims, design, methods, and descriptive statistics (nondietary). J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17: 591–608.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed as part of the research work of the Health Promotion Research Committee of the Shiga NHI Organizations. We are grateful to the Shiga NHI Organizations. This study was funded by research grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Comprehensive Research on Cardiovascular and Life-Style Related Disease: H17-kenko-007, H18-seishuu-012, H20-seishuu-013; H22-seishuu-012; Research on Cardiovascular Disease: 20K-6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

The Health Promotion Research Committee of the Shiga National Health Insurance Organizations

Chairman: Hirotsugu Ueshima.

Participating researchers: Shigeo Yamashita, Tomonori Okamura, Yoshinori Tominaga, Kazuaki Katsuyama, Fumihiko Kakuno and Machiko Kitanishi.

Associate researchers: Koshi Nakamura and Hideyuki Kanda.

Secretary members: Yukio Tobita, Kanehiro Okamura, Kiminobu Hatta, Takao Okada and Michiko Hatanaka.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, K., Okamura, T., Hayakawa, T. et al. Medical expenditures of men with hypertension and/or a smoking habit: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. Hypertens Res 33, 802–807 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.81

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.81

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The associations of multimorbidity with the sum of annual medical and long-term care expenditures in Japan

BMC Geriatrics (2019)

-

Tobacco use and household expenditures on food, education, and healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: a multilevel analysis

BMC Public Health (2015)

-

Smoking wears away happiness: New concept, ‘Smoking creates thunderclouds’

Hypertension Research (2010)