Abstract

The repeated phenotypic patterns that characterize populations undergoing parallel evolution provide support for a deterministic role of adaptation by natural selection. Determining the level of parallelism also at the genetic level is thus central to our understanding of how natural selection works. Many studies have looked for repeated genomic patterns in natural populations, but work on gene expression is less common. The studies that have examined gene expression have found some support for parallelism, but those studies almost always used samples collected from the wild that potentially confounds the effects of plasticity with heritable differences. Here we use two independent pairs of lake and stream threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) raised in common garden conditions to assess both parallel and antiparallel (that is, similar versus different directions of lake–stream expression divergence in the two watersheds) heritable gene expression differences as measured by total RNA sequencing. We find that more genes than expected by chance show either parallel (22 genes, 0.18% of expressed genes) or antiparallel (24 genes, 0.20% of expressed genes) lake–stream expression differences. These results correspond well with previous genomic studies in stickleback ecotype pairs that found similar levels of parallelism. We suggest that parallelism might be similarly constrained at the genomic and transcriptomic levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When organisms independently evolve similar phenotypes in similar environments, parallel (or convergent) evolution is typically inferred (Langerhans and DeWitt, 2004; Schluter et al., 2004; Arendt and Reznick, 2008; Losos, 2011; Wake et al., 2011). By quantifying the degree of this parallelism, it is possible to assess the role of deterministic natural selection, as opposed to more random processes such as genetic drift (or idiosyncratic selection or genetic architecture) (see, for example, Stuart et al., 2017). This exercise has been central to the long-standing debate in evolutionary biology regarding the relative contributions of contingent versus deterministic processes in evolutionary trajectories (see, for example, Gould, 1989, 2002; Travisano et al., 1995; Conway Morris, 2003; Burbrink et al., 2012; Mahler et al., 2013; Elmer et al., 2014a). If determinism is high, phenotypic parallelism should be high, and so too should be parallelism in the genetic pathways underlying the selected phenotypes. Theoretically, with the correct measurement of predictor variables, the outcome of evolution can be similarly forecast at both the phenotypic and genetic levels. If, on the other hand, chance historical events or other idiosyncratic effects are the stronger determinants of evolution, parallelism should be low; in this case, evolution appears to be a contingent process that is not as easily anticipated or predicted.

Over the past decade, many studies have sought to detect the effects of repeated natural selection at the genomic level, often attempting to specifically relate parallel phenotypic changes to parallel genetic changes (see, for example, Wilding et al., 2001; Storz and Nachman, 2003; Rogers and Bernatchez, 2007; Egan et al., 2008; Schluter et al., 2010; Kaeuffer et al., 2012; Roesti et al., 2012; Roda et al., 2013; Marques et al., 2016). Although these genetic changes can be either protein coding or regulatory, the relative contributions of these two possibilities is not often investigated (but see Jones et al., 2012). Yet, understanding the role of regulatory differences, which can be shaped by both genetic and plastic effects, is important because gene expression levels are subject to natural selection and can produce a phenotype independent of protein-coding sequences (Pritchard et al., 2017). Indeed, a genome scan of marine versus freshwater threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) revealed that divergent loci found in multiple, independent pairs of populations are more common in regulatory than in coding regions of the genome (Jones et al., 2012). Gene expression analysis can also reveal regulatory differences between populations that do not manifest as visible phenotypes (such as physiological differences), and therefore can be overlooked (Pavey et al., 2010). In addition, when gene expression differences are due to adaptive divergence, expression levels in hybrids and immigrants could produce fitness deficits that would contribute to ecologically based reproductive isolation (Pavey et al., 2010). In short, focusing solely on gene sequences can miss important differences between ecotypes that can reveal how natural selection is driving adaptive divergence and speciation. Looking for parallel gene expression, where a gene is repeatedly and significantly upregulated (or downregulated) in one environment type as compared with another environment type, thus allows for a more complete evaluation of the degree of determinism in adaptive divergence.

Studies of gene expression in populations undergoing adaptive divergence (and, putatively, ecological speciation) have become common in the past decade. Studying single pairs of populations, differences in gene expression have been found—as just a few examples—in dwarf versus normal whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) (Jeukens et al., 2010), upper versus lower shore periwinkle snails (Littorina saxatilis) (Martínez-Fernández et al., 2010), low- and high-predation guppies (Ghalambor et al., 2015) and lake versus stream threespine stickleback (G. aculeatus) (Lenz et al., 2013). These studies are valuable for understanding adaptive divergence in the specific studied populations; however, the lack of replication (only a single population pair was considered in each) means that the results cannot be generalized to adaptive divergence between those ecotypes as a whole. By instead studying multiple ecotype pairs, the degree of parallelism can be used to evaluate how important the deterministic process of natural selection is in promoting adaptive divergence in gene expression. A number of studies have taken this expanded ‘parallelism’ approach based on data from microarrays (see, for example, Derome et al., 2006; Lai et al., 2008; Filteau et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2014). Microarrays provide useful information but, compared whole-transcriptome methods (for example, RNA sequencing), will miss expression differences in genes not included on the array. Whole-transcriptome methods thus provide powerful tools for detecting parallel gene expression differences.

A growing number of studies avoid these first two limitations by analyzing whole transcriptomes for multiple population pairs—but a limitation remains. In particular, these studies have usually examined gene expression in wild-caught individuals (see, for example, Galindo et al., 2010; Manousaki et al., 2013; Westram et al., 2014) that will include an unknown combination of plastic and gene sequence effects on gene expression. Plasticity in such situations can either promote or constrain adaptive divergence (Pfennig et al., 2010; Moczek et al., 2011; Fitzpatrick, 2012; Ghalambor et al., 2015; Oke et al., 2016); but, importantly, plastic expression changes are not encoded by sequence changes, and therefore cannot be used to predict evolutionary trajectories. Yet, other studies have shown that gene expression variation often can be heritable and has contributed to adaptive divergence in several species (Pritchard et al., 2017). Indeed, a study of expression quantitative loci in stickleback found that up to 98% of transcripts expressed were under additive genetic control (Leder et al., 2014). In this study, we use a common garden design to remove plastic effects in multiple independent ecotype pairs, thereby allowing us to evaluate heritable parallelism in gene expression.

Study system

The threespine stickleback has become a model organism for studying parallel adaptive divergence because of the replication of independent ecotype pairs in a variety of environments (review: McKinnon and Rundle, 2002). One type of ecotype pair that has proven particularly useful in this regard is that formed by parapatric lake–stream populations (see, for example, Moodie, 1972; Reimchen et al., 1985; Lavin and McPhail, 1993; Deagle et al., 1996; Reusch et al., 2001; Hendry et al., 2002; Aguirre, 2009; Berner et al., 2010; Eizaguirre et al., 2011; Kaeuffer et al., 2012; Roesti et al., 2012; Lucek et al., 2013; Ravinet et al., 2013; Oke et al., 2016; Stuart et al., 2017). Throughout its range, the lake ecotype has generally evolved a shallower body and more numerous gill rakers; adaptations for sustained swimming in open water while feeding on limnetic prey (Caldecutt and Adams, 1998; Berner et al., 2008; Kaeuffer et al., 2012). In contrast, the stream ecotype has generally evolved a deeper body and fewer gill rakers; adaptations for swimming in complex, flowing environments while feeding on benthic macroinvertebrates (Caldecutt and Adams, 1998; Berner et al., 2008; Kaeuffer et al., 2012).

Recently, a number of studies have tested for parallelism in lake–stream stickleback genetic sequences, finding—as for phenotypes—a combination of parallel and nonparallel divergence patterns (see, for example, Thompson et al., 1997; Hendry and Taylor, 2004; Deagle et al., 2011; Kaeuffer et al., 2012; Roesti et al., 2012; Feulner et al., 2015; Marques et al., 2016; Stuart et al., 2017). In contrast, only two studies have investigated whole-transcriptome differences between lake and stream stickleback. The first (Lenz et al., 2013) examined gene expression in the head kidneys of a pair experimentally infected with parasites in a common garden. Although that study found significant overall (multivariate) expression differences in some fish, importantly, it did not test for expression differences of individual genes between the control (uninfected) lake and stream fish, nor did it test for parallelism. The second study looked at whole-transcriptome patterns in head kidneys and spleens of four lake–stream pairs (Huang et al., 2016). That study found 139 genes that were consistently and significantly upregulated in one habitat as compared with the other. However, its use of wild-caught individuals prevents insight into whether expression differences were genetic as opposed to plastic responses.

We build on these previous studies by assessing the level of parallelism in both overall and individual gene expression for common garden-raised stickleback from two lake–stream pairs. We also test for patterns of antiparallelism, when gene expression is negatively correlated between replicate pairs; for example, a gene that is upregulated in the lake (relative to the stream) population in one watershed but is downregulated in the lake (relative to the stream) population in another watershed. This additional exploration is not often taken in studies of parallelism, genetic or otherwise, possibly because of the relatively more straightforward interpretability of parallelism as opposed to antiparallelism (but see Derome et al., 2006). However, antiparallel differential expression patterns could influence parallel phenotypic patterns (Derome et al., 2006). Overall, the results of our study will address how genomic parallelism is reflected at the level of gene expression, an important step toward the ultimate goal of identifying genes that play a part in adaptive divergence via expression differences.

Materials and methods

Animal collection and rearing

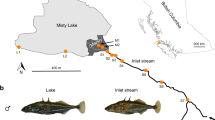

Between May and June 2013, we used unbaited minnow traps to sample stickleback from both the lake and stream of the Misty and Robert’s watersheds on Vancouver Island. These populations are in independent, isolated watersheds and have lake–stream average FST values for neutral loci of 0.121 and 0.045, respectively (Kaeuffer et al., 2012). Phenotypically, the two watersheds show pronounced parallelism between lake and stream fish (Kaeuffer et al., 2012; Stuart et al., 2017). Males in breeding condition and gravid females were retained and kept in coolers with air pumps for up to 8 h. We then killed the males and stripped eggs from the females in order to produce crosses using in vitro fertilization (each male was used to fertilize the eggs of only one female). We produced a pure-type cross from lake and stream of both Misty and Robert’s watersheds and kept fertilized egg masses in individual tubes at 4 °C for up to 4 days before they were shipped on ice to McGill University (Montreal, Canada). Once arrived (within 24 h), we transferred each egg mass to a separate 20 gallon aquarium in common garden conditions (identical husbandry conditions). Upon hatching, we fed the fish daily with brine shrimp and blood worms. We maintained the water in the tanks at 17 °C for the entire duration of the experiment. Light schedules were adjusted throughout the experiment to match the appropriate sunrise–sunset cycles on Vancouver Island in order that development would progress at a similar rate to that found in the natural habitat.

RNA sampling and library preparation

When the fish reached ∼2 years of age (range 663–703 days, because of differences in fertilization and birth dates), we used tricaine methanesulfonate to kill three randomly chosen fish from one stream family and one lake family from each of Misty and Robert’s watersheds, for a total of 12 fish. All fish were processed on the same day within 15 min of one another. Immediately after death we dissected the liver from the fish that was then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The liver was chosen because it is involved in a number of important processes in stickleback, including metabolism (Leder et al., 2009), cold tolerance (Orczewska et al., 2010), energy storage (Chellappa et al., 1989; Huntingford et al., 2001), immune function (Kurtz et al., 2006) and response to hypoxia (Leveelahti et al., 2011), all of which are related to the ecological differentiation between lake and stream sticklebacks. We then used the TRIzol Plus RNA Purification Kit (Thermo-Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to extract and purify total RNA. We prepared individual libraries using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and 100 bp, single-end reads were sequenced on two lanes of an Illumina HiSeq 2000, with libraries spread randomly over the two lanes.

Genome alignment

Raw reads were quality filtered before read mapping using the following steps. All raw reads output to fastq files were 100 bp in length. We used Trim Galore! 0.4.2 (Krueger, 2014) to remove sequencing adaptors and trim read tails with a PHRED quality score below 20. We kept reads that were longer than 20 bp after trimming. We then aligned trimmed reads to the stickleback genome (version 86) downloaded from www.ensembl.org using HISAT2 2.0.5 (Kim et al., 2015; Pertea et al., 2016) with at most one distinct, primary alignment for each read. Output SAM files from HISAT2 were then sorted and converted to BAM files using SAMtools 1.3 (Li et al., 2009; Li, 2011). Finally, we counted gene hits of aligned reads from BAM files using HTSeq 0.6.1p1 (Anders et al., 2014).

Differential expression analysis

All further analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015). We analyzed gene counts using the Bioconductor R Package edgeR 3.16.3 (Robinson et al., 2010). First, weakly expressed genes were filtered out if they had <1 count per million reads in three samples (Anders et al., 2013). All libraries were then simultaneously normalized with the TMM (trimmed mean of the M-value) method (Robinson and Oshlack, 2010) implemented in edgeR. The TMM method computes the scaling factors for the counts based on library size that were used in subsequent model fitting (see below). After applying the TMM method, most genes should have a unified expression level across all samples, and the scaling factors for all libraries should be close to 1 (Dillies et al., 2013). All of our libraries obtained scaling factors from 0.90 to 1.34. Next, the dispersion of the negative binomial distribution for the expression of each gene was estimated in edgeR. It represents the biological coefficient of variation of a gene’s expression. This was used to evaluate the expression variance, where a high dispersion value indicates high variance of gene expression pattern among samples. Finally, we produced a multidimensional scaling plot using the pairwise biological coefficient of variation as a distance measure to visualize the overall relationships between individuals (Figure 1).

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot between individual samples. Distances between individuals correspond to the leading biological coefficient of variation (BCV) that represents the biological (that is, nontechnical) variation. ML, Misty lake; MS, Misty stream; RL, Robert’s lake; RS, Robert’s stream.

We first used a non-parametric permutational multivariate analysis of variance to look for overall differences in gene expression between the two watersheds (D'haeseleer, 2005; Zapala and Schork, 2006; Lenz et al., 2013). We constructed a distance matrix using Pearson’s correlation in the R package amap (Lucas, 2014) on log counts per million (log2(CPM)) value for each gene. We then used this matrix as the response variable in a model with habitat (lake or stream), watershed (Misty or Robert’s) and their interaction as the independent variables. We ran 25 000 permutations using the adonis function in the R package vegan (Oksanen et al., 2015). We then tested for correlation between the log2 fold change (log2FC) between lake and stream in Misty as compared with Robert’s across all genes using Pearson’s product-moment (PPM) correlation coefficient. For this test, a significant positive correlation would indicate that generally genes that are up- or down-regulated in one watershed will show expression differences in the same direction in the other watershed, indicating a trend of parallelism, whereas an insignificant or negative correlation would support a lack of parallelism in overall gene expression between the two watersheds. More specifically, a significant negative correlation would indicate a general trend of antiparallelism, where genes up- or down-regulated in one watershed will show expression differences in the opposite direction in the other watershed.

We then used two methods to look for genes significantly differentially expressed in parallel (hereafter ‘DEP’) between the two watersheds. In the first (hereafter ‘GLM method’), we fit a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) with habitat (lake or stream), watershed (Misty or Robert’s) and their interaction as the explanatory variables. This model uses the Cox–Reid profile-adjusted likelihood method to estimate both the common and gene-wise dispersions. After model fitting and testing using likelihood ratio tests, we obtained lists of genes that were significantly differentially expressed (at a false discovery rate of 0.05) for the habitat term in Misty and Robert’s. We then found the overlap of those two lists and evaluated the probability of the observed overlap from the background of all expressed genes (after filtering) using the phyper function in R (which uses the hypergeometric distribution to calculate the probability of overlap without replacement). We then subtracted from the overlap list those genes that were significant for the habitat by watershed interaction to obtain a list of genes that should be DEP between lake and stream. As this method could exclude genes that have parallel expression in the two watersheds but with a larger difference in one than the other, leading to a significant interaction term, we used a second method to look for DEP genes that did not rely on the use of interaction terms.

In the second method (hereafter ‘Two-model method’), we fit two separate single-factor models for each watershed using the quantile-adjusted conditional maximum-likelihood method and tested for differential expression using the exact test. From both models we obtained a list of differentially expressed genes (with false discovery rate of <0.05), then extracted from those lists the genes that were found on both lists (the probability of the observed overlap was again tested using the phyper function in R) and showed expression differences in the same direction (for example, upregulated in stream in both cases).

We then extracted genes that were found on the DEP lists from both methods and considered these to be our final list of DEP genes. To further confirm that these genes showed similar expression patterns in both watersheds we tested for correlation in log2FC values between the two watersheds using the PPM correlation coefficient. To determine whether more genes were found to be DEP than expected by chance, we constructed a null distribution using permutations. To build the distribution we applied the permutation on the normalized read counts per gene, and randomly permuted the habitats (lake or stream) between libraries (that is, all reads for one individual) within the same watershed while maintaining the sample ID of each library. Each permutated data set was analyzed by the same steps used on the actual data and repeated 1000 times. We then calculated the probability of observing the number of genes that were shared between the two methods given this distribution.

We next tested for antiparallel gene expression. Using both the GLM and two-model methods, we looked for genes that showed patterns of significant negative correlation. Using the GLM method, we found the intersection between the list of genes that were differentially expressed for the habitat term in both Misty and Robert’s, and the list of genes that had a significant interaction term. As this method could include genes that do not show negatively correlated expression patterns but rather genes that show a larger degree of differential expression in one watershed than the other, we also used the two-model method. We first took the list of genes that were found to have differential expression between lake and stream in both watersheds. We then extracted from this list genes that showed opposite expression patterns in the two systems. We then made a list of the genes that were identified using both methods to be antiparallel, differentially expressed genes (hereafter ‘APDE’). The overall correlation between the log2FC values of these genes in both watersheds was quantified using the PPM correlation coefficient. Using the same simulations as described above, we constructed a null distribution of the number of genes expected to be APDE under random processes.

Functional analyses

We tested for the enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms in our DEP and APDE gene sets with the Bioconductor R package topGO 2.26.0 (Alexa et al., 2006), based on Fisher’s exact tests. The gene pools against which we compared the DEP or APDE gene sets were the genes having passed the filtering step and entering the differential expression analyses (see above). Overrepresented GO terms were those with a multiple test corrected P-value (Benjamini–Hochberg’s false discovery rate) below 0.05.

Results

Transcriptome mapping

After trimming for quality, each library was composed of an average of 33 710 122 reads. On average, 86.24% of reads aligned to the stickleback genome, and 13.21% of these mapped to multiple regions of the genome that were subsequently excluded from further analyses. Out of the 22 455 annotated genes retrieved from the stickleback genome (Ensembl version 86), an average of 16 543 genes were found expressed, and 12 300 genes were found expressed across all samples after filtering out weakly expressed genes as described above, and hence were kept for further analysis.

Overall gene expression

The first axis of the multidimensional scaling plot separated the two watersheds from one another, whereas the second axis separated habitats, although to a different degree in each watershed (Figure 1). The results of the permutational multivariate analysis of variance concur with the patterns displayed in the multidimensional scaling plot, with watershed explaining 33.86% of the variation (F=6.584, P=8.00 × 10−5), habitat explaining 12.94% of the variation (F=2.516, P=0.037) and the interaction explaining a further 12.05% of the variation (F=2.35, P=0.049). The PPM coefficient on log2FC values for Misty versus Robert’s found a weak but significant positive correlation (ρ=0.08, P=2.2 × 10−16) (solid line in Figure 2).

Scatterplot of log2FC values in Misty versus Robert’s. Colors for differential expression in Misty only, Robert’s only and neither are based on results from the two-model method. Colors for DEP and APDE are based on agreement between both methods. Gray points represent genes that were found to be DEP in the two-model method but not the GLM method. Solid line indicates correlation between all genes, dashed line indicates correlation between DEP genes and dotted line indicates correlation between APDE genes. DE, significantly differentially expressed.

Individual genes differentially expressed in parallel

Using the GLM method, we found 384 and 667 genes significantly differentially expressed between Misty lake and stream, and Robert’s lake and stream, respectively. Of these genes, 59 were found on both lists. The probability of this amount of overlap or more occurring by chance is 6.95 × 10−14. Of these 59 genes, 32 also had a significant interaction term, meaning that the expression difference between habitats was different in the two watersheds, indicating nonparallelism. This left a list of 27 genes that were DEP between the two watersheds (Figure 3).

Venn diagrams showing the number of genes found to be DEP (shown in bold) in both methods. In GLM method, circles show the number of genes significantly differentially expressed in the Misty and Robert’s watersheds, and the number of genes found to have a significant habitat by watershed interaction (thereby indicating nonparallelism). The overlap between the two upper circles therefore represents DEP genes. In the two-model method, circles show the number of genes significantly differentially expressed in the Misty and Robert’s watersheds, and the number of genes with directional expression differences (thereby indicating parallelism). The overlap between all three circles therefore represents DEP genes. Lower diagram shows the DEP gene list overlap between the DEP lists derived from each method as shown in the upper diagrams.

Using the two-model method, we found 321 and 616 genes differentially expressed between Misty lake and stream, and Robert’s lake and stream, respectively. There were 53 genes in common between the two watersheds. The probability of this overlap or greater by chance is 2.17 × 10−15. Of these genes, 28 were differentially expressed in the same direction (DEP) in both watersheds (Figure 3).

The intersect of the GLM and two-model methods gave us our final list of 22 DEP genes (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S1). These genes showed a significant correlation in log2FC between Misty and Robert’s (dashed line in Figure 2; ρ=0.95, P=2.67 × 10−11). This 22 is a much greater number than expected by chance; the P-value for having the same 22 genes shared by both methods was 0.004. Half of the 22 genes had a negative log2FC value, meaning they were upregulated in lakes, whereas the remaining 11 genes were upregulated in streams. Differential expression between habitats was greater for those genes upregulated in the lake: the mean log2FC of these genes was −4.79 as compared with 2.81 for genes upregulated in streams. Genes upregulated in lakes also tended to be more strongly expressed, with the mean of the mean lake expression for those genes being 511 CPM. In comparison, mean stream expression for the 11 genes that were upregulated in streams had a mean of 65 CPM.

We also found slight differences in expression between watersheds; in the Misty watershed, mean DEP gene expression in lake and stream fish was 299 and 67 CPM, respectively, whereas in the Robert’s watershed, mean DEP gene expression in lake and stream fish was 220 and 83 CPM, respectively. Across all 12 300 genes (not just those that were DEP), Misty stickleback had mean gene expression of 80 and 89 CPM in the lake and stream, respectively, whereas Robert’s stickleback had mean gene expression of 80 and 78 CPM in the lake and stream, respectively. The magnitude of differential expression was similar between watersheds; for genes upregulated in lake, the mean log2FC was −5.47 in Misty and −4.11 in Robert’s and for genes upregulated in stream, mean log2FC in Misty was 2.84 and 2.78 in Robert’s.

Of the 22 DEP genes, 9 are novel and thus do not have known functions. The remaining 13 genes reflect a range of functions (Supplementary Table S1).

Antiparallel gene expression

Using the GLM method, we found that 32 of the 59 genes that were differentially expressed between lake and stream in both watersheds also had a significant interaction term, and hence were identified as being APDE. Using the two-model method, 25 of the 53 genes that were differentially expressed between lake and stream in both watersheds were expressed in opposite directions, and were classified as APDE. The overlap between the genes identified with each method was 24 that constituted the final list of APDE genes (Supplementary Table S2). There was a strong negative correlation between the log2FC values between watersheds of these 24 genes (dotted line in Figure 2, ρ=−0.92, P=1.54 × 10−10). Finally, the list of 24 APDE genes was significantly more than would be expected by chance; the P-value for having the same 24 genes shared by both methods was 0.004.

Of the 24 APDE genes, 13 were novel and do not have any known function in fish (Supplementary Table S2). Of the 11 remaining genes, most do not have known functions in teleosts.

Functional analyses of DEP and APDE genes

Both the DEP and APDE genes had no significant GO term enrichment (false discovery rate <0.05). The top GO terms for DEP genes were ionotropic glutamate receptor activity (GO: 0004970) in Molecular Function, intracellular (GO: 0005622) in Cellular Component and branchiomeric skeletal muscle development (GO: 0014707) in Biological Process. The top GO terms for APDE genes were adenoine deaminase activity (GO: 004000) in Molecular Function, intermediate filament (GO: 0005882) in Cellular Component and neural tube formation (GO: 0001841) in Biological Process.

Discussion

Our goal was to determine the level of parallelism in heritable gene expression for repeated cases of adaptive divergence. This work is an important complement to the many studies seeking to quantify parallel variation in genomic sequences, and thereby infer if the same mutations are repeatedly used during the process of adaptive divergence. These studies have generally found equivocal or variable answers; some genomic differences (typically evaluated by scanning for FST-outlier loci) are repeated, but many others are not (Nosil et al., 2009; Elmer and Meyer, 2011; Roda et al., 2013; Soria-Carrasco et al., 2014; Elmer et al., 2014b). As an example of parallelism, 1.4% of markers were FST outliers in all four pairs of dwarf and normal lake whitefish (Campbell and Bernatchez, 2004), and the same was true for 5% of the markers in four pairs of upper- and lower-shore ecotypes of the rough periwinkle (Littorina saxatalis) (Wilding et al., 2001). As other examples, between 0.2% (Jones et al., 2012) and 2.5% (Hohenlohe et al., 2010a) of the genome shows repeated differentiation between marine and freshwater populations of threespine stickleback. As an example in our study system—lake–stream stickleback—0.2% of single-nucleotide polymorphisms were located in parallel ‘islands of genomic differentiation’ in multiple pairs (Marques et al., 2016).

Yet, other studies, often focusing on the same species in which parallel genomic signatures were found (as above), find little or no evidence for parallel differentiation; no overlap was found for outlier loci between two parallel cichlid radiations (Kautt et al., 2012), or in five normal and dwarf lake whitefish pairs (Renaut et al., 2011). This lack of parallel outliers could be because of the low number of markers used: 1030 amplified fragment length polymorphism markers and 112 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the cichlid and whitefish studies, respectively. However, improved marker density does not always lead to the detection of parallel genetic differentiation; studies using 8417 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (Roesti et al., 2012) and whole-genome sequences (Feulner et al., 2015) found that none of the significant FST-outlier peaks found in lake–stream stickleback pairs were shared among all 4 and 5 populations, respectively, that were studied.

Overall gene expression differences

Given the wide range of genomic parallelism described above, we expected to find some parallelism in gene expression for lake versus stream stickleback, but did not know how large a fraction of expression it would represent. First looking for parallelism in overall gene expression, we found that habitat (lake versus stream) explained ∼13% of the total variation, but that the magnitude of the difference between lake and stream stickleback was larger in the Robert’s system than in the Misty system (Figure 1). This pattern for gene expression (some parallelism in direction but considerable differences in magnitude) is similar to the patterns of phenotypic parallelism found in other studies of lake and stream stickleback. For example, Berner et al. (2010) compared lake–stream stickleback pairs from Vancouver Island (Canada) and Switzerland, finding that body shape differed in a consistent direction between lake and stream fish, whereas the magnitude of the difference was much greater on Vancouver Island than in Switzerland. Even in populations that are much closer geographically, differences in the magnitude of divergence can be dramatic. For instance, Berner et al. (2009) examined phenotypic divergence in six Vancouver Island lake–stream pairs and found that, although distance downstream from a lake was a significant predictor of body depth and gill raker number, the strength of this distance–trait association varied dramatically among watersheds.

The parallel aspect of overall gene expression divergence documented here was also evident in the significant positive correlation between the log2FC values in Misty versus Roberts. This trend confirms that a gene upregulated in one habitat type (lake or stream) in the Misty watershed tended (on average) to be upregulated in that same habitat type in the Robert’s watershed. Testing for such parallelism in overall gene expression is not common, with the focus typically being on just the genes showing significant differential expression (see, for example, Derome et al., 2006; St‐Cyr et al., 2008; Manousaki et al., 2013). This focused approach on individual genes could underestimate the true degree of expression parallelism if many of the expression differences between ecotypes are small, and this might be expected if adaptive divergence is driven by (the expression of) many genes of small effect. This potential inability to detect small effect loci is also present in studies looking at sequence differentiation between populations through the use of outlier genome scans; loci of small effect, especially those selected by soft sweeps (selection of standing genetic variation), can be missed in such scans (Storz, 2005; Teshima et al., 2006; Hohenlohe et al., 2010b), leading to an underestimate of parallel loci.

Our finding of overall differentiation in gene expression between lake and stream stickleback is contrary to the results found by Lenz et al. (2013), where overall gene expression did not differ between the lab-raised lake and stream fish that served as experimental controls (that is, had not been exposed to parasites). Many possible reasons exist for these contrasting results, including the different tissues used: head kidneys for Lenz et al. (2013) versus liver in our study. Although the liver plays a role in many processes in stickleback (see Materials and methods), head kidneys are frequently used to investigate immunological functions because of their high degree of specialization (see, for example, Kurtz et al., 2006; Bolnick et al., 2015; Stutz et al., 2015). Other potential reasons for the difference between studies could be the use of different populations (northern Germany versus Vancouver Island) that have different genetic histories (including standing genetic variation in the marine ancestor and time since colonization and divergence) and presumably different selection regimes (prey and predator communities, degree of human influence, temperature and so on). Differences could also be because of the ages of the fish (∼8.5 months for Lenz et al., 2013 versus 24 months in our study). More work will be necessary to establish how differences in overall gene expression might be context specific.

Differential expression of individual genes

Examination of the individual genes that show parallel differential expression is valuable, because these outliers are likely important in divergent adaptation. We found 22 such genes, representing 0.18% of all stickleback genes, and 0.20% of these genes that were minimally expressed (see Materials and methods). In comparison, a study of wild-caught lake–stream pairs found 73 genes differentially expressed in parallel in head kidney tissue and 74 in spleen tissue, representing 0.33% of all stickleback genes in each case (Huang et al., 2016). That the number of DEP genes is almost triple in wild-caught fish as compared with lab-raised fish is not surprising; exposure to parasites, interactions with predators, changing abiotic variables and varied diets are all stimuli not encountered in the benign lab environment that could all promote gene expression (either heritable or plastic) in wild fish. Indeed, Lenz et al. (2013) found that lab-raised lake and stream fish showed differential gene expression only when exposed to parasites multiple times, suggesting that many expression differences occur only in response to particular stimuli. Studies of parallel gene expression in other species have also shown variability in the percentage of genes found to be DEP. In microarray studies, 0.06% (Lai et al., 2008), 1.35% (Derome et al., 2006) and 2.39% (St‐Cyr et al., 2008) of genes were differentially expressed in parallel between multiple population pairs. Of course, caution must be used in comparing microarray experiments to the present whole-transcriptome study because genes chosen a priori to be included on a microarray might not be representative of the whole transcriptome.

How do the above numbers for gene expression parallelism compare with estimates of genomic parallelism at the sequence level? Of the two studies that have looked for genomic parallelism in lake–stream stickleback, one found three loci (0.31 to 0.35% of all single-nucleotide polymorphisms examined, depending on watershed) that were outliers in all three watersheds examined (Deagle et al., 2011), whereas the other found no outliers in all four watersheds examined (Roesti et al., 2012). Considering that the fish in our study were only expressing ∼55% of all possible stickleback genes after filtering weakly expressed genes (12 300 of 22 455), 0.18% seems not unexpectedly low. More studies on sequence divergence between lake and stream ecotypes would allow for a more thorough exploration of the relationship between parallelism in sequence and gene expression.

Potential functional roles of DEP genes

Of the 13 DEP genes with known function, 2 are from protein families shown to have a role in immune functions in fish: sigirr (single immunoglobulin and Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain), which plays a role in inhibiting hepatic inflammation in zebrafish (Danio rerio) (Feng et al., 2016), and a TRIM gene, trim35-12 (tripartite motif containing 35-12), implicated in antiviral innate immunity in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (van der Aa et al., 2009). Interestingly, four TRIM genes from the same TRIM family as that found in the present study (35-12) were found to show signatures of balancing selection in three freshwater and two oceanic stickleback populations (Hohenlohe et al., 2010a). The increase in polymorphism produced by this balancing selection could play a role in stickleback immunity similar to that seen in other teleosts (Hohenlohe et al., 2010a). Finally, in zebrafish (D. rerio), TRIM genes have been found in the same genetic regions as the major histocompatibility complex and its paralogs (Boudinot et al., 2011); immune genes that have the potential to drive reproductive isolation between lake and stream stickleback populations (Eizaguirre et al., 2011).

Of course, the hypothesis that these DEP loci are associated with immune function depends on the gene expression being constitutive, as part of the innate immune system, as the fish were raised in common garden and not exposed to parasites and thus should not have any challenge to the immune system that would activate adaptive immunity (at least not differently between lake and stream). Indeed, studies in stickleback have found significant genetic variation in innate parasite immunity (Wegner et al., 2007). Regardless, most of the genes upregulated in lake fish, including myom1b and pacsin1b, which are involved in myogenesis (Lo et al., 2003) and embryonic notochord development (Edeling et al., 2009), respectively, are unlikely to have immune functions. The reason for upregulation in lakes for these genes is therefore an open question, but this study provides a basis for considering these as candidate genes in determining the genetic basis of divergent adaptation.

Similarly, the 10 genes that were upregulated in stream fish do not have obvious functional roles in the phenotypic divergence between lake and stream populations. The top two differentially expressed genes, akr1b1 and ret, do not have known functions in adult teleost fish. However, two of the other genes do: as3mt (arsenite methyltransferase) and cry1ab (cryptochrome circadian clock 1ab). As3mt is involved in arsenic detoxification and has been found to be upregulated in livers of zebrafish exposed to arsenic (Hamdi et al., 2012). Arsenic, which accumulates in the livers of fish (Maher et al., 1999; Mason et al., 2000; Kirby and Maher, 2002), tends to be high in benthic-feeding fish (Kirby and Maher, 2002; Bordajandi et al., 2003; de Rosemond et al., 2008). Stream stickleback on Vancouver Island have been shown to have diets higher in benthic prey items than lake fish (Berner et al., 2008, 2009; Kaeuffer et al., 2012), and thus may be exposed to higher levels of dietary arsenic than lake fish. cry1ab is part of the cryptochrome protein family that is involved in regulation of the circadian clock in zebrafish (Kobayashi et al., 2000; Lahiri et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2015) and Atlantic cod (Lazado et al., 2014). Sexual maturation in stickleback is dependent on photoperiod (Borg, 1982; Baggerman, 1985; Borg et al., 2004) and the optimal time for breeding could differ between lake and stream (but see Hanson et al., 2016). Overall, the functional roles for the stream upregulated DEP genes are unclear, but future experiments examining expression of these genes in more detail would be valuable.

Antiparallel genes

Another goal of our study was to formally test for genes differentially expressed in an antiparallel manner. We found 24 such genes in our two lake–stream pairs, more than expected by chance. This result intuitively suggests that some aspect of lake–stream divergence—that what is influenced by these antiparallel genes—must also be antiparallel. Indeed, antiparallel phenotypic divergence for some morphological traits is evident for lake–stream stickleback in the Robert’s versus Misty watersheds (Oke et al., 2016), for lake–stream stickeback in other watersheds (Hendry and Taylor, 2004; Kaeuffer et al., 2012) and for many other fishes (Oke et al., 2017). Recent work has attributed some of this lake–stream phenotypic antiparallelism to antiparallel divergence in lake–stream habitat features (Stuart et al., 2017) and therefore, presumably, antiparallel divergence in lake–stream natural selection.

Alternatively, it is possible that antiparallel gene expression may produce parallel phenotypes (Manousaki et al., 2013) that could occur if genetic constraints drive different balances of up- and down-regulation of genes within the same or similar pathways that have functionally similar effects (Derome et al., 2006). This scenario is not unlikely given that parallel phenotypes are often underlain by expression of different genes. As examples, decreased Pitx1 expression causes pelvic reduction in some, but not all populations of stickleback; and, similarly, decreased expression of Agouti is associated with dark coat color in some, but not all, populations of Peromyscus maniculatus mice (Linnen et al., 2009). Although we did not find obvious functional similarities across the different APDE genes, which would suggest they might contribute to the same phenotype but through different expression, many of the APDE genes are not well characterized functionally. For instance, 12 of the 24 APDE genes are novel, and the majority of the remainder have not been functionally characterized in teleosts. As with the DEP genes, these genes represent possible candidate genes on which to focus future research.

Limitations

We finally want to address some of the deficiencies that could be addressed in future work. A first issue was the limited number of population pairs—finding the same DEP (or APDE) genes in more pairs would strengthen claims of their adaptive importance. Of course, nonparallelism can increase with an increasing number of ecotype pairs. For example, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway was the only strong candidate for parallel evolution in four pairs of pollutant-sensitive and -tolerant Atlantic killifish (Reid et al., 2016). A second issue was the low number of individuals per population; however, the three individuals per site did have similar expression in most cases (Figure 1). A third issue was the use of one family per population, whereas more families would inform family-level variation, including differences in social behavior between families (or populations) and parental effects. However, previous gene expression work in lake–stream stickleback found no significant family effect (Lenz et al., 2013), and the trends shown in Figure 1 suggest overall expression levels separate mainly by habitat and watershed, a pattern that would be unlikely if family-level variation was more important. Fourth, fish from the different populations were of slightly different ages at sampling because of differences in fertilization date and days until hatching. However, all fish in this study were past the major developmental stages (Swarup, 1958), and hence should not have major differences in gene expression due to development. Finally, we used only liver tissue from adult individuals, whereas gene expression is known to be specific to tissue and development stage. Thus, using a different tissue, or sampling from embryos or juvenile fish, might have given us different lists of genes. Taking these limitations into account, this work represents a first but necessary step toward a more comprehensive evaluation of parallel gene expression.

General conclusions

Our study contributes toward a greater understanding of the relationship between parallelism in genomic sequences and gene expression patterns that are associated with those sequences. Specifically, we examined heritable, total gene expression patterns in multiple pairs of adaptively divergent populations. We also introduce a novel method of evaluating the number of genes found to be expressed in parallel (or antiparallel) using a permutation approach to construct a null distribution that allows for an empirical assessment of significance. Although we found some parallel gene expression, the vast majority of gene expression was nonparallel (that is, nondivergent or antiparallel), in line with expectations based on genome-wide patterns of sequence variation. This result suggests that, at this molecular level, deterministic natural selection plays a relatively small role in shaping evolutionary trajectories. Alternatively, it could be that genetic or environmental factors are sufficiently different between the Misty and Robert's systems that parallel evolution of gene expression is unlikely, even if natural selection is playing a strong role. For example, if the two systems started with different standing genetic variation, had dissimilar levels of gene flow or have different environmental pressures such as parasites, predators and abiotic factors, we would not expect parallel gene expression patterns. In addition, the potential exists for gene expression to be influenced by genotype–environment interactions (G × E) that could reduce parallelism (Oke et al., 2016). Future work could test these hypotheses. Parallel genetic mechanisms, at both the expression and sequence levels, appear to be present at similarly low levels in populations that exhibit repeated adaptive divergence, a pattern that is important for our understanding of the role of natural selection in parallel evolution.

Data accessibility

R code and gene count files: https://github.com/barrettlabecoevogeno/Analysis-of-parallel-evolution-in-lake-stream-sticklebacks.

References

Aguirre WE . (2009). Microgeographical diversification of threespine stickleback: body shape-habitat correlations in a small, ecologically diverse Alaskan drainage. Biol J Linn Soc 98: 139–151.

Alexa A, Rahnenführer J, Lengauer T . (2006). Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22: 1600–1607.

Anders S, McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Okoniewski M, Smyth GK, Huber W et al. (2013). Count-based differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data using R and Bioconductor. Nat Protoc 8: 1765–1786.

Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W . (2014). HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169.

Arendt J, Reznick D . (2008). Convergence and parallelism reconsidered: what have we learned about the genetics of adaptation? Trends Ecol Evol 23: 26–32.

Baggerman B . (1985). The roles of daily and annual biological rhythms in the photoperiodic regulation of the breeding season in the stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus L. Behaviour 93: 1–7.

Berner D, Adams DC, Grandchamp A-C, Hendry AP . (2008). Natural selection drives patterns of lake-stream divergence in stickleback foraging morphology. J Evol Biol 21: 1653–1665.

Berner D, Grandchamp A-C, Hendry AP . (2009). Variable progress toward ecological speciation in parapatry: stickleback across eight lake-stream transitions. Evolution 63: 1740–1753.

Berner D, Roesti M, Hendry AP, Salzburger W . (2010). Constraints on speciation suggested by comparing lake-stream stickleback divergence across two continents. Mol Ecol 19: 4963–4978.

Bolnick DI, Shim KC, Schmerer M, Brock CD . (2015). Population-specific covariation between immune function and color of nesting male threespine stickleback. PLoS One 10: e0126000.

Bordajandi LR, Gómez G, Fernandez M, Abad E, Rivera J, González MJ . (2003). Study on PCBs, PCDD/Fs, organochlorine pesticides, heavy metals and arsenic content in freshwater fish species from the River Turia (Spain). Chemosphere 53: 163–171.

Borg B . (1982). Seasonal effects of photoperiod and temperature on spermatogenesis and male secondary sexual characters in the three-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus L. Can J Zool 60: 3377–3386.

Borg B, Bornestaf C, Hellqvist A, Schmitz M, Mayer I . (2004). Mechanisms in the photoperiodic control of reproduction in the stickleback. Behaviour 141: 1521–1530.

Boudinot P, van der Aa LM, Jouneau L, Du Pasquier L, Pontarotti P, Briolat V et al. (2011). Origin and evolution of TRIM proteins: new insights from the complete TRIM repertoire of zebrafish and pufferfish. PLoS One 6: e22022.

Burbrink FT, Chen X, Myers EA, Brandley MC, Pyron RA . (2012). Evidence for determinism in species diversification and contingency in phenotypic evolution during adaptive radiation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 279: 4817–4826.

Caldecutt WJ, Adams DC . (1998). Morphometrics of trophic osteology in the threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Copeia 1998: 827–838.

Campbell D, Bernatchez L . (2004). Generic scan using AFLP markers as a means to assess the role of directional selection in the divergence of sympatric whitefish ecotypes. Mol Biol Evol 21: 945–956.

Chellappa S, Huntingford F, Strang R, Thomson R . (1989). Annual variation in energy reserves in male three‐spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus L.(Pisces, Gasterosteidae). J Fish Biol 35: 275–286.

Conway Morris S . (2003) Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

D'haeseleer P . (2005). How does gene expression clustering work? Nat Biotechnol 23: 1499–1502.

de Rosemond S, Xie Q, Liber K . (2008). Arsenic concentration and speciation in five freshwater fish species from Back Bay near Yellowknife, NT, Canada. Environ Monit Assess 147: 199–210.

Deagle BE, Jones FC, Chan YF, Absher DM, Kingsley DM, Reimchen TE . (2011). Population genomics of parallel phenotypic evolution in stickleback across stream–lake ecological transitions. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 279: 1277–1286.

Deagle BE, Reimchen TE, Levin DB . (1996). Origins of endemic stickleback from the Queen Charlotte Islands: mitochondrial and morphological evidence. Can J Zool 74: 1045–1056.

Derome N, Duchesne P, Bernatchez L . (2006). Parallelism in gene transcription among sympatric lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis Mitchill) ecotypes. Mol Ecol 15: 1239–1249.

Dillies MA, Rau A, Aubert J, Hennequet-Antier C, Jeanmougin M, Servant N et al. (2013). A comprehensive evaluation of normalization methods for Illumina high-throughput RNA sequencing data analysis. Brief Bioinform 14: 671–683.

Edeling MA, Sanker S, Shima T, Umasankar PK, Honing S, Kim HY et al. (2009). Structural requirements for PACSIN/Syndapin operation during zebrafish embryonic notochord development. PLoS One 4: e8150.

Egan SP, Nosil P, Funk DJ . (2008). Selection and genomic differentiation during ecological speciation: isolating the contributions of host association via a comparative genome scan of Neochlamisus bebbianae leaf beetles. Evolution 62: 1162–1181.

Eizaguirre C, Lenz TL, Sommerfeld RD, Harrod C, Kalbe M, Milinski M . (2011). Parasite diversity, patterns of MHC II variation and olfactory based mate choice in diverging three-spined stickleback ecotypes. Evol Ecol 25: 605–622.

Elmer KR, Fan S, Kusche H, Spreitzer ML, Kautt AF, Franchini P et al. (2014a). Parallel evolution of Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fishes via non-parallel routes. Nat Commun 5: 1–8.

Elmer KR, Fan S, Kusche H, Spreitzer ML, Kautt AF, Franchini P et al. (2014b). Parallel evolution of Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fishes via non-parallel routes. Nat Commun 5: 1–8.

Elmer KR, Meyer A . (2011). Adaptation in the age of ecological genomics: insights from parallelism and convergence. Trends Ecol Evol 26: 298–306.

Feng W, Gu Y-F, Nie L, Guo D-Y, Xiang L-X, Shao J-Z . (2016). Characterization of SIGIRR/IL-1R8 homolog from zebrafish provides new insights into its inhibitory role in hepatic inflammation. J Immunol 197: 151–167.

Feulner PG, Chain FJ, Panchal M, Huang Y, Eizaguirre C, Kalbe M et al. (2015). Genomics of divergence along a continuum of parapatric population differentiation. PLoS Genet 11: e1004966.

Filteau M, Pavey SA, St-Cyr J, Bernatchez L . (2013). Gene coexpression networks reveal key drivers of phenotypic divergence in lake whitefish. Mol Biol Evol 30: 1384–1396.

Fitzpatrick BM . (2012). Underappreciated consequences of phenotypic plasticity for ecological speciation. Int J Ecol 2012, Article ID 256017.

Galindo J, Grahame J, Butlin R . (2010). An EST‐based genome scan using 454 sequencing in the marine snail Littorina saxatilis. J Evol Biol 23: 2004–2016.

Ghalambor CK, Hoke KL, Ruell EW, Fischer EK, Reznick DN, Hughes KA . (2015). Non-adaptive plasticity potentiates rapid adaptive evolution of gene expression in nature. Nature 525: 372–375.

Gould SJ . (1989). A developmental constraint in Cerion, with comments of the definition and interpretation of constraint in evolution. Evolution 43: 516–539.

Gould SJ . (2002) The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

Hamdi M, Yoshinaga M, Packianathan C, Qin J, Hallauer J, McDermott JR et al. (2012). Identification of an S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) dependent arsenic methyltransferase in Danio rerio. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 262: 185–193.

Hanson D, Barrett R, Hendry A . (2016). Testing for parallel allochronic isolation in lake–stream stickleback. J Evol Biol 29: 47–57.

Hendry AP, Taylor EB . (2004). How much of the variation in adaptive divergence can be explained by gene flow? An evaluation using lake-stream stickleback pairs. Evolution 58: 2319–2331.

Hendry AP, Taylor EB, McPhail JD . (2002). Adaptive divergence and the balance between selection and gene flow: lake and stream stickleback in the Misty system. Evolution 56: 1199–1216.

Hohenlohe PA, Bassham S, Etter PD, Stiffler N, Johnson EA, Cresko WA . (2010a). Population genomics of parallel adaptation in threespine stickleback using sequenced RAD tags. PLoS Genet 6: e1000862.

Hohenlohe PA, Phillips PC, Cresko WA . (2010b). Using population genomics to detect selection in natural populations: key concepts and methodological considerations. Int J Plant Sci 171: 1059.

Huang Y, Chain FJ, Panchal M, Eizaguirre C, Kalbe M, Lenz TL et al. (2016). Transcriptome profiling of immune tissues reveals habitat‐specific gene expression between lake and river sticklebacks. Mol Ecol 25: 943–958.

Huntingford F, Chellappa S, Taylor A, Strang R . (2001). Energy reserves and reproductive investment in male three‐spined sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Ecol Freshwat Fish 10: 111–117.

Jeukens J, Renaut S, St-Cyr J, Nolte AW, Bernatchez L . (2010). The transcriptomics of sympatric dwarf and normal lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis spp., Salmonidae) divergence as revealed by next-generation sequencing. Mol Ecol 19: 5389–5403.

Jones FC, Grabherr MG, Chan YF, Russell P, Mauceli E, Johnson J et al. (2012). The genomic basis of adaptive evolution in threespine sticklebacks. Nature 484: 55–61.

Kaeuffer R, Peichel CL, Bolnick DI, Hendry AP . (2012). Parallel and nonparallel aspects of ecological, phenotypic, and genetic divergence across replicate population pairs of lake and stream stickleback. Evolution 66: 402–418.

Kautt AF, Elmer KR, Meyer A . (2012). Genomic signatures of divergent selection and speciation patterns in a ‘natural experiment’, the young parallel radiations of Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fishes. Mol Ecol 21: 4770–4786.

Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL . (2015). HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 12: 357–360.

Kirby J, Maher W . (2002). Tissue accumulation and distribution of arsenic compounds in three marine fish species: relationship to trophic position. Appl Organomet Chem 16: 108–115.

Kobayashi Y, Ishikawa T, Hirayama J, Daiyasu H, Kanai S, Toh H et al. (2000). Molecular analysis of zebrafish photolyase/cryptochrome family: two types of cryptochromes present in zebrafish. Genes Cells 5: 725–738.

Krueger F . (2014). Trim Galore! Version 0.4.2. Available from www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/.

Kurtz J, Wegner KM, Kalbe M, Reusch TB, Schaschl H, Hasselquist D et al. (2006). MHC genes and oxidative stress in sticklebacks: an immuno-ecological approach. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 273: 1407–1414.

Lahiri K, Vallone D, Gondi SB, Santoriello C, Dickmeis T, Foulkes NS . (2005). Temperature regulates transcription in the zebrafish circadian clock. PLoS Biol 3: e351.

Lai Z, Kane NC, Zou Y, Rieseberg LH . (2008). Natural variation in gene expression between wild and weedy populations of Helianthus annuus. Genetics 179: 1881–1890.

Langerhans RB, DeWitt TJ . (2004). Shared and unique features of evolutionary diversification. Am Nat 164: 335–349.

Lavin PA, McPhail JD . (1993). Parapatric lake and stream sticklebacks on northern Vancouver Island: disjunct distribution or parallel evolution? Can J Zool 71: 11–17.

Lazado CC, Kumaratunga HP, Nagasawa K, Babiak I, Giannetto A, Fernandes JM . (2014). Daily rhythmicity of clock gene transcripts in Atlantic cod fast skeletal muscle. PLoS One 9: e99172.

Leder EH, McCairns RS, Leinonen T, Cano JM, Viitaniemi HM, Nikinmaa M et al. (2014). The evolution and adaptive potential of transcriptional variation in sticklebacks—signatures of selection and widespread heritability. Mol Biol Evol 32: 674–689.

Leder EH, Merilä J, Primmer CR . (2009). A flexible whole-genome microarray for transcriptomics in three-spine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus. BMC Genomics 10: 426.

Lenz TL, Eizaguirre C, Rotter B, Kalbe M, Milinski M . (2013). Exploring local immunological adaptation of two stickleback ecotypes by experimental infection and transcriptome-wide digital gene expression analysis. Mol Ecol 22: 774–786.

Leveelahti L, Leskinen P, Leder E, Waser W, Nikinmaa M . (2011). Responses of threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus, L) transcriptome to hypoxia. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics 6: 370–381.

Li H . (2011). A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27: 2987–2993.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N et al. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079.

Linnen CR, Kingsley EP, Jensen JD, Hoekstra HE . (2009). On the origin and spread of an adaptive allele in deer mice. Science 325: 1095–1098.

Liu C, Hu J, Qu C, Wang L, Huang G, Niu P et al. (2015). Molecular evolution and functional divergence of zebrafish (Danio rerio cryptochrome genes. Sci Rep 5: 8113.

Lo J, Lee S, Xu M, Liu F, Ruan H, Eun A et al. (2003). 15,000 unique zebrafish EST clusters and their future use in microarray for profiling gene expression patterns during embryogenesis. Genome Res 13: 455–466.

Losos JB . (2011). Convergence, adaptation, and constraint. Evolution 65: 1827–1840.

Lucas A . (2014) R package version 0.8-14. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=amap.

Lucek K, Sivasundar A, Roy D, Seehausen O . (2013). Repeated and predictable patterns of ecotypic differentiation during a biological invasion: lake–stream divergence in parapatric Swiss stickleback. J Evol Biol 26: 2691–2709.

Maher W, Goessler W, Kirby J, Raber G . (1999). Arsenic concentrations and speciation in the tissues and blood of sea mullet (Mugil cephalus from Lake Macquarie NSW, Australia. Mar Chem 68: 169–182.

Mahler DL, Ingram T, Revell LJ, Losos JB . (2013). Exceptional convergence on the macroevolutionary landscape in island lizard radiations. Science 341: 292–295.

Manousaki T, Hull PM, Kusche H, Machado‐Schiaffino G, Franchini P, Harrod C et al. (2013). Parsing parallel evolution: ecological divergence and differential gene expression in the adaptive radiations of thick‐lipped Midas cichlid fishes from Nicaragua. Mol Ecol 22: 650–669.

Marques DA, Lucek K, Meier JI, Mwaiko S, Wagner CE, Excoffier L et al. (2016). Genomics of rapid incipient speciation in sympatric threespine stickleback. PLoS Genet 12: e1005887.

Martínez-Fernández M, Bernatchez L, Rolán-Alvarez E, Quesada H . (2010). Insights into the role of differential gene expression on the ecological adaptation of the snail Littorina saxatilis. BMC Evol Biol 10: 1.

Mason R, Laporte J-M, Andres S . (2000). Factors controlling the bioaccumulation of mercury, methylmercury, arsenic, selenium, and cadmium by freshwater invertebrates and fish. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 38: 283–297.

McKinnon JS, Rundle HD . (2002). Speciation in nature: the threespine stickleback model systems. Trends Ecol Evol 17: 480–488.

Moczek AP, Sultan S, Foster S, Ledón-Rettig C, Dworkin I, Nijhout HF et al. (2011). The role of developmental plasticity in evolutionary innovation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 278: 2705–2713.

Moodie GEE . (1972). Predation, natural selection and adaptation in an unusual threespine stickleback. Heredity 28: 155–167.

Morris MR, Richard R, Leder EH, Barrett RD, Aubin‐Horth N, Rogers SM . (2014). Gene expression plasticity evolves in response to colonization of freshwater lakes in threespine stickleback. Mol Ecol 23: 3226–3240.

Nosil P, Harmon LJ, Seehausen O . (2009). Ecological explanations for (incomplete) speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 24: 145–156.

Oke K, Bukhari M, Kaeuffer R, Rolshausen G, Räsänen K, Bolnick D et al. (2016). Does plasticity enhance or dampen phenotypic parallelism? A test with three lake–stream stickleback pairs. J Evol Biol 29: 126–143.

Oke KB, Rolshausen G, LeBlond C, Hendry AP . (2017). How parallel is parallel evolution? A comparative analysis in fishes. Am Nat 190: 1–16.

Oksanen J, Kindt R, Legendre P, O’Hara B, Stevens MHH, Oksanen MJ et al. (2015) R package version 2.3-1. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Orczewska JI, Hartleben G, O'Brien KM . (2010). The molecular basis of aerobic metabolic remodeling differs between oxidative muscle and liver of threespine sticklebacks in response to cold acclimation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R352–R364.

Pavey SA, Collin H, Nosil P, Rogers SM . (2010). The role of gene expression in ecological speciation. Ann NY Acad Sci 1206: 110–129.

Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL . (2016). Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc 11: 1650–1667.

Pfennig DW, Wund MA, Snell-Rood EC, Cruickshank T, Schlichting CD, Moczek AP . (2010). Phenotypic plasticity's impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 25: 459–467.

Pritchard VL, Viitaniemi HM, McCairns RS, Merilä J, Nikinmaa M, Primmer CR et al. (2017). Regulatory architecture of gene expression variation in the Threespine Stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus. G3 (Bethesda) 7: 165–178.

Ravinet M, Prodöhl PA, Harrod C . (2013). Parallel and nonparallel ecological, morphological and genetic divergence in lake-stream stickleback from a single catchment. J Evol Biol 26: 186–204.

Reid NM, Proestou DA, Clark BW, Warren WC, Colbourne JK, Shaw JR et al. (2016). The genomic landscape of rapid repeated evolutionary adaptation to toxic pollution in wild fish. Science 354: 1305–1308.

Reimchen TE, Stinson EM, Nelson JS . (1985). Multivariate differentiation of parapatric and allopatric populations of threespine stickleback in the Sangan River watershed, Queen Charlotte Islands. Can J Zool 63: 2944–2951.

Renaut S, Nolte AW, Rogers SM, Derome N, Bernatchez L . (2011). SNP signatures of selection on standing genetic variation and their association with adaptive phenotypes along gradients of ecological speciation in lake whitefish species pairs (Coregonus spp.. Mol Ecol 20: 545–559.

Reusch TBH, Wegner KM, Kalbe M . (2001). Rapid genetic divergence in postglacial populations of threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus): the role of habitat type, drainage and geographical proximity. Mol Ecol 10: 2435–2445.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK . (2010). edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140.

Robinson MD, Oshlack A . (2010). A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 11: R25.

Roda F, Liu H, Wilkinson MJ, Walter GM, James ME, Bernal DM et al. (2013). Convergence and divergence during the adaptation to similar environments by an Australian groundsel. Evolution 67: 2515–2529.

Roesti M, Hendry AP, Salzburger W, Berner D . (2012). Genome divergence during evolutionary diversification as revealed in replicate lake-stream stickleback population pairs. Mol Ecol 21: 2852–2862.

Rogers S, Bernatchez L . (2007). The genetic architecture of ecological speciation and the association with signatures of selection in natural lake whitefish (Coregonus sp. Salmonidae) species pairs. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1423–1438.

Schluter D, Clifford EA, Nemethy M, McKinnon JS . (2004). Parallel evolution and inheritance of quantitative traits. Am Nat 163: 809–822.

Schluter D, Marchinko KB, Barrett RDH, Rogers SM . (2010). Natural selection and the genetics of adaptation in threespine stickleback. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 365: 2479–2486.

Soria-Carrasco V, Gompert Z, Comeault AA, Farkas TE, Parchman TL, Johnston JS et al. (2014). Stick insect genomes reveal natural selection’s role in parallel speciation. Science 344: 738–742.

St‐Cyr J, Derome N, Bernatchez L . (2008). The transcriptomics of life‐history trade‐offs in whitefish species pairs (Coregonus sp.. Mol Ecol 17: 1850–1870.

Storz JF . (2005). Using genome scans of DNA polymorphism to infer adaptive population divergence. Mol Ecol 14: 671–688.

Storz JF, Nachman MW . (2003). Natural selection on protein polymorphism in the rodent genus Peromyscus: evidence from interlocus contrasts. Evolution 57: 2628–2635.

Stuart YE, Veen T, Weber JN, Hanson D, Ravinet M, Lohman BK et al. (2017). Contrasting effects of environment and genetics generate a continuum of parallel evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 1, Article ID 0158.

Stutz WE, Schmerer M, Coates JL, Bolnick DI . (2015). Among‐lake reciprocal transplants induce convergent expression of immune genes in threespine stickleback. Mol Ecol 24: 4629–4646.

Swarup H . (1958). Stages in the development of the stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus (L.). Development 6: 373–383.

Teshima KM, Coop G, Przeworski M . (2006). How reliable are empirical genomic scans for selective sweeps? Genome Res 16: 702–712.

Thompson CE, Taylor EB, McPhail JD . (1997). Parallel evolution of lake-stream pairs of threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus inferred from mitochondrial DNA variation. Evolution 51: 1955–1965.

Travisano M, Mongold JA, Bennett AF, Lenski RE . (1995). Experimental tests of the roles of adaptation, chance, and history in evolution. Science 267: 87–90.

van der Aa LM, Levraud J-P, Yahmi M, Lauret E, Briolat V, Herbomel P et al. (2009). A large new subset of TRIM genes highly diversified by duplication and positive selection in teleost fish. BMC Biol 7: 1.

Wake DB, Wake MH, Specht CD . (2011). Homoplasy: from detecting pattern to determining process and mechanism of evolution. Science 331: 1032–1035.

Wegner KM, Kalbe M, Reusch TB . (2007). Innate versus adaptive immunity in sticklebacks: evidence for trade-offs from a selection experiment. Evol Ecol 21: 473–483.

Westram A, Galindo J, Alm Rosenblad M, Grahame J, Panova M, Butlin R . (2014). Do the same genes underlie parallel phenotypic divergence in different Littorina saxatilis populations? Mol Ecol 23: 4603–4616.

Wilding CS, Butlin RK, Grahame J . (2001). Differential gene exchange between parapatric morphs of Littorina saxatilis detected using AFLP markers. J Evol Biol 14: 611–619.

Zapala MA, Schork NJ . (2006). Multivariate regression analysis of distance matrices for testing associations between gene expression patterns and related variables. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 19430–19435.

Acknowledgements

Foremost, the work of Yué Jiao and Caroline Leblond in the care and sampling of stickleback was indispensable in the success of this study. Thanks also to Elena Motivans, Mingsha Zhou and Krista Oke for their help in the field, and to Western Forest Products for providing accommodation on Vancouver Island. Freddy Chain, Katie Peichel, Anna Greenwood and David Morais gave valuable assistance with bioinformatics. Library preparation and transcriptome sequencing was performed at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre. DH was supported through a Natural Sciences and Research Council (NSERC) of Canada PGS-D grant. JH was supported by a China Scholarship Council (CSC) State Scholarship Fund Award. APH was supported by a NSERC Discovery Grant. RDHB was supported by a NSERC Discovery grant and a Canada Research Chair.

Author contributions

DH, APH and RDHB conceived of the study; DH ran the experiment and collected the data; DH and JH analyzed the data; and DH wrote the manuscript with input from JH, APH and RDHB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hanson, D., Hu, J., Hendry, A. et al. Heritable gene expression differences between lake and stream stickleback include both parallel and antiparallel components. Heredity 119, 339–348 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2017.50

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2017.50

This article is cited by

-

Genetic assimilation of ancestral plasticity during parallel adaptation to zinc contamination in Silene uniflora

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Evolution of novel genes in three-spined stickleback populations

Heredity (2020)