Abstract

The X chromosome is a relatively large chromosome, harboring a lot of genetic information. Much of the statistical analysis of X-chromosomal information is complicated by the fact that males only have one copy. Recently, frequentist statistical tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium have been proposed specifically for dealing with markers on the X chromosome. Bayesian test procedures for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for the autosomes have been described, but Bayesian work on the X chromosome in this context is lacking. This paper gives the first Bayesian approach for testing Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with biallelic markers at the X chromosome. Marginal and joint posterior distributions for the inbreeding coefficient in females and the male to female allele frequency ratio are computed, and used for statistical inference. The paper gives a detailed account of the proposed Bayesian test, and illustrates it with data from the 1000 Genomes project. In that implementation, a novel approach to tackle multiple testing from a Bayesian perspective through posterior predictive checks is used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of genetic markers identified for the human genome has increased tremendously over the past decades. The 1000 Genomes project currently include more than 88 million genetic variants (The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2015). Most of the variants reside on the autosomes, which are ordered according to their size. The X chromosome is a large chromosome with a size of about 155 Mb, and is almost as large as chromosome 7 (Hein et al., 2005), and estimated to contain about 5% of the genes in the human genome (Wise et al., 2013). Currently, ~3.5 million variants on the X chromosome have been reported. Much of the statistical analysis of the X-chromosomal data is complicated by the fact that males have only one copy, whereas females have two. The pseudo-autosomal regions (Graves et al., 1998) of the X chromosome behave as autosomes, and for these regions autosomal statistical methodology applies.

A simple way to deal with X-chromosomal data is to ignore males, and apply usual autosomal procedures to females only. This is what often has been done in studies of Hardy–Weinberg (HW) equilibrium, linkage disequilibrium, genetic association studies (Wise et al., 2013) and others. The HW law is a well-known elementary genetic principle typically explained in detail in genetic textbooks (Crow and Kimura, 1970; Li, 1976; Hartl, 1980; Hamilton, 2009). For a biallelic marker with alleles A and B with relative frequencies p and q, the law states that the genotype frequencies AA, AB and BB will reach the stable proportion (p2, 2pq, q2) in one generation of random mating. From this point on, genotype and allele frequencies will remain unaltered through time, as long as disturbing forces like differential mortality, migration and others remain absent.

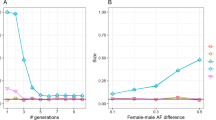

The dynamics of X-chromosomal markers is quite different. If male and female allele frequencies initially differ then it will take more than one generation before equilibrium is achieved. Because A males inherit their A allele from their mother, the male A allele frequency always equals the female A allele frequency of the previous generation. Because females inherit one allele from each parent, the female A allele frequency is the mean of the male and female A allele frequency of the previous generation. This ‘lagging and averaging’ continues till the difference between male and female allele frequencies becomes vanishingly small. At that point, the female genotype frequencies will have stabilized as well, reaching the HW proportions. In each generation, the absolute difference between male and female allele frequencies is halved. If Dt represents the absolute difference in male and female allele frequency in generation t then we have Dt=(1/2)tD1, with D1 the initial generation. In a worst case scenario with D1=1, it will take eight generations in total before the difference drops below 0.01. Figure 1 illustrates the faster attainment of HW equilibrium for smaller values of D1.

Statistical tests for HW equilibrium should reflect the special characteristics of the X chromosome. In recent work, Graffelman and Weir (2016) have proposed χ2, exact and permutation tests for HW equilibrium for markers at the X chromosome that take both males and females into account. You et al. (2015) have developed a likelihood ratio test for X-chromosomal markers that also uses males and females. These frequentist procedures jointly test HW proportions for females and equality of allele frequencies in males and females.

There is a considerable number of contributions to the Bayesian testing for HW equilibrium of autosomal markers, starting with Pereira and Rogatko (1984) and Lindley (1988), and including Shoemaker et al. (1998), Ayres and Balding (1998) and Wakefield (2009, 2010). Bayesian methods have also been used to deal with variants of unknown location, and classify them as autosomal or X-chromosomal under the assumption of HW equilibrium (Gautier, 2014). For testing autsomal variants for HW equilibrium, Ayres and Balding (1998) proposed a markov chain monte carlo method to obtain the posterior distributions of inbreeding coefficients for markers with multiple alleles. Shoemaker et al. (1998) obtained explicit expressions for the joint posteriors of various disequilibrium coefficients and allele frequencies in the biallelic case. Wakefield (2010) advocates the use of the Bayes factor in Bayesian inference on HW equilibrium and addresses Bayesian testing in a genome-wide context. However, all these Bayesian studies address autosomal markers, and to date Bayesian procedures for X-chromosomal markers have apparently not been developed. This paper therefore first proposes Bayesian methods for a HW analysis of X-chromosomal markers that take both males and females into account, by using an extra parameter allowing for different allele frequencies in the sexes. We concentrate on the most commonly used single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and consider markers with multiple alleles, such as micro-satellites, beyond the scope of the current paper.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the ‘Background and notation’ section, we provide some background and establish notation. In the ‘Bayesian tests for X-chromosomal markers’ section, we develop a Bayesian approach to the problem of testing X-chromosomal markers for HW equilibrium, and we assess the method through simulation. The ‘Examples’ section illustrates the use of the Bayesian approach with empirical data taken from the Japanese population of the 1000 Genomes project (The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2010), both for single SNPs as well as sets of multiple X-chromosomal SNPs. The approach adopted in that implementation to deal with multiple testing through posterior predictive checks is novel. A discussion section completes the paper.

Background and notation

We consider a biallelic genetic polymorphism on the X chromosome with alleles A and B having allele frequencies pAm and pBm in males and pAf and pBf in females, with pAm+pBm=pAf+pBf=1. There are five genotypes consisting of hemizygous males, with genotypes A and B, and diploid females, with genotypes AA, AB and BB. We denote the observed genotype counts in males by nAm and nBm, and in females by nAAf, nABf and nBBf. The total sample size is n=nm+nf, where nm=nAm+nBm is the total number of males, and where nf=nAAf+nABf+nBBf is the total number of females.

The male A genotype (or allele) count, nAm, is assumed to follow a Binomial(nm, pAm) distribution, and the vector of female genotype counts, (nAAf, nABf, nBBf), is assumed to follow a Multinomial(nf, (pAAf, pABf, pBBf)) distribution, where pAAf+pABf+pBBf=1.

Equilibrium in X-chromosomal markers

For X-chromosomal markers, it can take more generations to achieve equilibrium, depending on the initial difference in allele frequency between the sexes (Crow and Kimura, 1970). In fact, under disequilibrium, allele and genotype frequencies for the X chromosome will always be changing from generation to generation. All the frequencies considered next correspond to the current generation.

HW equilibrium holds for the SNPs of the X chromosome if and only if:

-

1

There is equality of male and female allele frequencies, pAm=pAf,

-

2

The female genotype counts, (nAAf, nABf, nBBf), are multinomially distributed with HW proportions

When both these conditions hold in one generation then, under random mating, the allele frequencies in males and the genotype frequencies in females are constant from one generation to the next (see, for example, Li (1976) and Zheng et al. (2007)). In the case of X-chromosomal markers, disequilibrium can be present under three different scenarios.

In the first scenario, pAm=pAf holds, but the female genotype proportions fail to match the HW proportions, a case which is typically parametrized in terms of a female inbreeding coefficient, f, such that:

When pAm=pAf, a value of f=0 corresponds to HW equilibrium, a positive f indicates a lack of female heterozygotes, and a negative f indicates an excess of female heterozygotes. Hence, for studying this first kind of disequilibrium on the X chromosome, we will use this female inbreeding coefficient, f, as a measure of the deviation of female genotype frequencies from HW proportions in the current generation, which can be posed as:

Note that the value of f can range between −MAF/(1−MAF) and 1, where MAF=min(pAf, 1−pAf). Under this first disequilibrium scenario and random mating, one will have HW equilibrium in the next generation, like for autosomal markers.

Under a second disequilibrium scenario, female genotype probabilities satisfy HW proportions and therefore f=0, but the allele frequencies between males and females are different and therefore condition 1 does not hold, in which case we use as a measure for disequilibrium the ratio of male to female allele frequencies,

Under this second disequilibrium scenario, with d≠1, allele frequencies of males and genotype frequencies of females converge to equilibrium only when the number of generations goes to infinity; even though in this setting in the current generation f is 0, in the previous and in the following generations f is different from 0.

Under a third disequilibrium scenario, X-chromosomal markers might not be in equilibrium because both f≠0 as well as d≠1.

Models for equilibrium and for disequilibrium

In practice one will face either the HW equilibrium scenario, or one of three disequilibrium scenarios, which leads to the choice between four models. Under HW equilibrium, female genotype counts have the Multinomial distribution with pAm=pAf. In this case, the value of pAf determines the value of all the remaining probabilities. The model under HW equilibrium will be labeled as Model 0, (M0).

distribution with pAm=pAf. In this case, the value of pAf determines the value of all the remaining probabilities. The model under HW equilibrium will be labeled as Model 0, (M0).

In the first disequilibrium scenario described above, f≠0 and d=1, and female genotype counts have the Multinomial(nf, (pAAf, pABf, pBBf)) distribution, while male A genotype counts follow the Binomial(nm, pAm) distribution with:

In this case the value of (pAAf,pABf) determines the value of all the remaining probabilities. The model for this disequilibrium scenario is labeled as Model 1, (M1).

In the second disequilibrium scenario described in the ‘Equilibrium in X-Chromosomal markers’ section, the inbreeding coefficient for females, f, is equal to 0, but d is not equal to 1. In that case, female genotype counts have the Multinomial distribution, while the male A genotype count follows the Binomial(nm, pAm) distribution with probability pAm functionally unrelated to pAf. In this case, the value of (pAf, pAm) determines the value of all the remaining probabilities. The model for this second disequilibrium scenario is labeled as Model 2, (M2).

distribution, while the male A genotype count follows the Binomial(nm, pAm) distribution with probability pAm functionally unrelated to pAf. In this case, the value of (pAf, pAm) determines the value of all the remaining probabilities. The model for this second disequilibrium scenario is labeled as Model 2, (M2).

In the third and last disequilibrium scenario, f≠0 and d≠1. In that case, female genotype counts are multinomial with unrestricted probabilities, as in Model 1, while the male A genotype count is binomially distributed with probability pAm, as in Model 2. In this case, the parameter space is the largest possible, and the model is labeled as Model 3, (M3), or the saturated model.

Bayesian tests for X-chromosomal markers

In the frequentist approach to testing for HW equilibrium for X-chromosomal markers presented in Graffelman and Weir (2016), one chooses between HW equilibrium, (that is, Model 0), and disequilibrium, (that is, Models 1, 2 and 3), but it does not allow one to distinguish between the three different disequilibrium scenarios. In the frequentist approach, additional statistical tests for equality of allele frequencies and/or HW proportions in females would be needed to finally pinpoint the scenario.

Instead, in the Bayesian setting it is more natural to test for HW equilibrium by choosing one scenario among the four alternative scenarios described above, which is equivalent to selecting one model among M0, M1, M2 and M3. That is done by choosing a prior distribution for the parameters of the models that captures what one knows about them before observing the data, and a prior distribution on the model space, and then computing the posterior probability of each one of the four models (scenarios). Then, one selects the model (scenario) with largest posterior probability.

Choice of a prior distribution

Different parametrizations allow for different ways of capturing what one knows about the parameters of the model in terms of a prior distribution for them. Here we will adopt the parametrization of Models 0, 1, 2 and 3 in terms of male and female genotype frequencies, because that allows for a choice of priors that leads to simple expressions for the posterior probabilities of the four models considered, and because they are the most convenient ones when one has little information.

Under the HW equilibrium scenario, leading to Model 0, male and female allele frequencies, pAm and pAf, are equal, and they will be assumed to be Beta(b1,0, b2,0) distributed, where the second subindex, 0, refers to M0. Under this scenario, this prior distribution univocally determines the prior distribution of all female genotype frequencies.

Under the first disequilibrium scenario, leading to Model 1, the female genotype frequencies, (pAAf, pABf, pBBf), are assumed to be Dirichlet(a1,1,f, a2,1,f, a3,1,f) distributed, where the second subindex, 1, refers to M1. The distribution of the female genotype frequencies determines the distribution of the female and male allele frequencies.

Under the second disequilibrium scenario, leading to Model 2, male and female allele frequencies are assumed to be independently distributed as a Beta(b1,2,m, b2,2,m) and Beta(b1,2,f, b2,2,f), respectively, and that determines the distribution of the female genotype frequencies. Finally, under the last disequilibrium scenario, leading to Model 3, female genotype frequencies are assumed to be Dirichlet(a1,3,f, a2,3,f, a3,3,f) distributed, independent of the male allele frequency, which is assumed to be Beta(b1,3,m, b2,3,m) distributed.

Depending on the values chosen for (a1,i,f, a2,i,f, a3,i,f), the Dirichlet(a1,i,f, a2,i,f, a3,i,f) distribution will be more or less informative, and it will capture different information about female genotype frequencies. In particular, its expected value is  , and one can choose the aj,i,f’s to reflect the fact that one expects some genotypes to have larger probabilities than others. Also, the larger

, and one can choose the aj,i,f’s to reflect the fact that one expects some genotypes to have larger probabilities than others. Also, the larger  the smaller the variances of the components of the Dirichlet random variable, and the more informative that prior distribution. When one is not willing to use subjective information about the female genotype frequencies, Berger et al. (2015) recommend using a Dirichlet with a1,i,f=a2,i,f=a3,i,f=1/3, which is also recommended by Bernardo and Tomazella (2010) as a good approximation to a prior distribution tailored for a reference analysis of HW equilibrium. We will use this reference prior, which is like assuming an effective sample size of only one to start with (see, for example, Morita et al. (2008)). Given that the actual sample sizes in our setting will typically be a lot larger than that, the impact of this prior on the posterior distribution for female genotype frequencies will be negligible.

the smaller the variances of the components of the Dirichlet random variable, and the more informative that prior distribution. When one is not willing to use subjective information about the female genotype frequencies, Berger et al. (2015) recommend using a Dirichlet with a1,i,f=a2,i,f=a3,i,f=1/3, which is also recommended by Bernardo and Tomazella (2010) as a good approximation to a prior distribution tailored for a reference analysis of HW equilibrium. We will use this reference prior, which is like assuming an effective sample size of only one to start with (see, for example, Morita et al. (2008)). Given that the actual sample sizes in our setting will typically be a lot larger than that, the impact of this prior on the posterior distribution for female genotype frequencies will be negligible.

An analogous argument can be made for choosing the parameters of the Beta(b1,i, b2,i) to model the prior information about allele frequencies. In that case, in the absence of subjective information one often chooses Beta(b1,i, b2,i) with b1,i=b2,i=1/2, which corresponds to a relatively uninformative prior that assumes an effective sample size of only one to start with. Moreover, this prior captures the fact that low MAF markers are more frequent.

An alternative way of eliciting prior information under Models 1 and 3 is to choose a specific distribution for the inbreeding coefficient, f, and for the female allele frequency, pAf, instead of resorting to the Dirichlet distribution for the genotype frequencies. However, this complicates the computation of the posterior probabilities, and it does not make much difference when carrying out a reference analysis that uses little prior information. The inbreeding coefficient is related to the female genotype frequencies through:

and one can explore the prior distribution of f that is induced by assuming a Dirichlet distribution on (pAAf, pABf, pBBf). When one does that for our reference choice, with a1,i,f=a2,i,f=a3,i,f=1/3, one finds that the prior distribution for f is not symmetric on its support. That prior is in fact trimodal, with two modes at the two extremes of the range of values taken by f, and a third mode at 0, which are features that one considers desirable for a reference prior for a parameter such as f, with finite range and a null hypothesis at 0. Furthermore, under our choice of parameters for the Dirichlet prior, one can check through Monte-Carlo simulation that the probability that f is larger than 0 is 0.548.

Instead, when one assumes a Dirichlet(a1,i,f, a2,i,f, a3,i,f) distribution with a1,i,f=a2,i,f=a3,i,f=1 as the prior distribution for the female genotype frequencies, which corresponds to assuming a uniform distribution on them, one finds that the prior distribution for f concentrates on values larger than 0, with a prior probability that f is larger than 0 equal to 0.667. The problem of this upward bias introduced when using a uniform distribution has already been reported by Foll and Gaggiotti (2008). Another shortcoming of assuming a uniform prior for (pAAf, pABf, pBBf) is that the prior induced on the female allele probability through pAf=(2pAAf+pABf)/2 becomes strongly unimodal with mode at 0.5. Instead, our choice of a1,i,f=a2,i,f=a3,i,f=1/3 leads to a prior distribution for pAf that is a lot closer to the Beta(0.5, 0.5) that is assumed for pAm.

Note though that either one of these two choices of values for (a1,i,f, a2,i,f, a3,i,f) leads to posterior distributions that are very similar, because they are both a lot less informative than the data that one typically obtains in these settings.

Alternative ways of choosing prior distributions for HW equilibrium under the usual autosomal data can be found in Lindley (1988), Shoemaker et al. (1998), Consonni et al. (2008) and Wakefield (2010). All their proposals could be adapted to our X-chromosomal marker setting, but if one chose these priors to have a small effective sample size, they would make a small difference at a considerable extra computational cost, because they do not lead to closed form expressions for the posterior probabilities described next.

Bayesian model selection

The Bayesian way to select a model is through the posterior probability of each model, P(Mi|y), which is the probability that the Mi model is the one generating the data, y=(nAAf, nABf, nBBf, nAm, nBm), assessed after the data has been observed. It can be computed by using Bayes theorem:

where P(Mi) is the prior probability assigned to Mi (that is, the probability that this model is correct, assessed before the data are available), and where P(y|Mi) is the marginal likelihood of Mi. If all models were considered equally likely a priori, the way it will be assumed in the ‘Examples’ section, the larger P(y|Mi), the more attractive Mi will be.

Most often, computing P(y|Mi) exactly is too complicated, and the marginal likelihoods need to be estimated through the markov chain monte carlo simulations used to update the model. In our Binomial/Multinomial setting with Beta/Dirichlet priors though, there are closed form expressions for P(y|Mi), which allow one to either compute these marginal likelihoods exactly, in the case of Models 0, 2 and 3, or to evaluate them numerically in the case of Model 1. The expressions for the marginal likelihoods, P(y|Mi), under our choice of prior distribution can be found in the Appendix 1; they allow one to compute the posterior probabilities on the model space, P(Mi|y), exactly through equation (3.2).

To assess the strength of evidence in favor or against a given model, Mi, one sometimes resorts to the corresponding Bayes factor, BFi, which is the ratio of the posterior odds and the prior odds for that model. When all four models are considered equally likely a priori, BFi=3P(Mi|y)/(1−P(Mi|y)). One usually considers that a log10(BFi) that takes a value between 0.5 and 1 indicates that the strength of evidence in favor of Mi is substantial, when its value is between 1 and 1.5 it is strong, when it is between 1.5 and 2 it is very strong, and when it is larger than 2 it considers the evidence in favor of Mi to be decisive.

Simulation assessment of the Bayesian test

To assess the performance of this Bayesian test for HW equilibrium, here it is used under a very wide set of known scenarios through an extensive simulation study. In particular, the test is tried on SNPs from populations with inbreeding coefficients, f, taking values in its whole range, and with a ratio of male to female allele frequencies, d, ranging between 0.5 and 2. In total, we have considered 625 different pairs of values for (f, d), and for each pair we have checked the performance of the test on populations with pAf=0.2 and 0.4 assuming samples with nf=nm=500 and with nf=nm=2000.

For each one of the set of 2500 values of (f, d, pAf, nf) considered we have simulated 1000 independent SNPs with sample size n=nf+nm from a population with the corresponding values of (f, d, pAf), and we have computed P(Mi|y) for i=0,1,2,3 and for each one of the samples.

Figure 2 presents the contour plots for the average of all the values of P(Mi|y) obtained, as a function of (f, d) for the four combinations of (pAf, nf) considered. This average estimates the expected value of P(Mi|y) for each given (f, d, pAf, nf). As desirable, the expected value of P(Mi|y) peaks on the region of the (f, d) space where the corresponding Mi model holds true. One also observes that the larger the sample size n, and/or the larger pAf, the more peaked the expected value of P(Mi|y) is as a function of (f, d), and hence the better does this Bayesian test work.

Examples

To present applications of the Bayesian approach to testing for HW equilibrium advocated in this paper, we analyze individual markers (see the ‘Test on four individual SNPs’ section) and groups of markers (see the ‘Simultaneous analysis of multiple X-chromosomal SNPs’ section) of the Japanese population of the 1000 Genomes project, consisting of nm=56 males and nf=48 females. We also explain how one can take into account the multiple testing effect through posterior predictive checks when assessing the HW equilibrium hypothesis based on the simultaneous analysis of a large number of SNPs (see the ‘Multiple testing and the assessment of HW equilibrium’ section).

Test on four individual SNPs

In order to compare the Bayesian test proposed here for HW equilibrium at biallelic genetic markers on the X chromosome with the tests proposed in the context of a frequentist approach, we report the posterior probabilities of the four possible scenarios together with the P-values of the exact tests for four example SNPs in Table 1. Exact tests were performed with and without the data on males using the methods proposed by Graffelman and Weir (2016). The posterior probabilities are computed through equation (3.2), assuming equal prior probabilities for the four models, and hence P(Mi)=1/4, and using the expressions for the marginal likelihoods, P(y|Mi) in the Appendix 1 with aj,i,f=1/3 for the Dirichlet prior and bj,i=1/2 for the Beta priors. Given that each one of these priors corresponds to an effective sample size of only one and data involves a sample size of n=104, the role played by the prior distribution is negligible. Sample sizes will most often be larger than in this example, and hence in practice the choice of a prior will most often be even less relevant.

The first marker in Table 1, rs13440889, has a posterior probability of 0.748 of being in HW equilibrium, and hence one rejects the three disequilibrium scenarios, with posterior probabilities of 0.126 or smaller. The corresponding Bayes factor indicates that the evidence in favor of being in HW equilibrium here is substantial. This is consistent with the non-significant exact test for HWE (P=0.954). The second marker in Table 1 has a posterior probability of only 0.072 of being in HW equilibrium, but it has instead a posterior probability of 0.803 of being in the first disequilibrium scenario, with d=1 and f≠0, and hence one settles with M1 for that marker. Here the Bayes factor indicates that the evidence in favor of M1 is strong. In this case, choosing M1 is in agreement with the frequentist exact test rejecting HW proportions in females (P=0.004).

For the third marker in Table 1, HW equilibrium is also rejected, because it has a posterior probability of only 0.092, and one settles with the second disequilibrium scenario, with d≠1 and with f=0. Note that in this case, the frequentist tests do reject HWE overall, but do not reject HW proportions for females (P=0.760). For the last marker in Table 1, the most probable scenario is clearly the third disequilibrium scenario, with d≠1 and f≠0. Here BF3 indicates that the evidence in favor of M3 is decisive. The frequentist tests reject equilibrium (P<0.0005), but the difference in allele frequencies goes unnoticed.

In Figure 3, one has the set of marginal posterior distributions for the marker in the second row in Table 1, SNP rs2301322. These marginal posteriors are computed assuming the full Model 3, in the way described in Appendix 2. The first row presents the marginal posterior for female genotype frequencies, the second row presents the marginal posterior for male and female allele frequencies and for their ratio, while the third row presents the marginal posterior for the inbreeding coefficient as well as the joint posterior for allele frequencies and for (f, d).

Marginal posterior distributions and 90% hpd posterior credible region of female genotype frequencies, of male and female allele frequencies, of the ratio of male to female allele frequencies and of the inbreeding coefficient, and marginal joint posterior distributions of (pAf,pAm) and of (f, d), all for SNP rs2301322 in Table 1, under the saturated Model.

Figure 3 also presents 90% highest posterior density (hpd) credible intervals/regions for all these parameter values or pairs of parameter values. The marginal posterior for f in Figure 3, for example, places almost all its probability mass away from f=0, with the 90% hpd posterior credible interval being (0.199, 0.683). Instead, the marginal posterior for d places d=1 well inside its 90% hpd posterior credible interval, which is (0.853, 1.172). The results clearly show that females are out of HW proportions, but that equality of male and female allele frequencies is a tenable supposition.

Note that different from confidence regions, Bayesian credible regions are statements about the probability that the actual parameter value for that given SNP falls in a given region, and not the probability that the region captures the true parameter value under repeated use of these regions on different samples.

Figure 4 presents the marginal posterior distributions for (f, d) for the four SNPs in Table 1, together with its 90% hpd posterior credible region. The fact that, for example, for the SNP rs13440889, the (0, 1) point falls well inside the 90% posterior credible region is a clear indication that in that case HW equilibrium holds. In the other three examples, the (0, 1) point falls outside the corresponding 90% credible region in three different ways, which are representative of the three different reasons through which equilibrium might be broken.

Marginal joint posterior distributions and 90% hpd posterior credible region for (f, d) for the four SNPs considered in Table 1, under the saturated Model.

Simultaneous analysis of multiple X-chromosomal SNPs

In this section, we illustrate the Bayesian approach to testing for HW equilibrium of X-chromosomal markers by carrying out the Bayesian test based on the simultaneous analysis of a large set of SNPs selected from the Japanese population of the 1000 Genome project. The 1000 Genomes project provides genotype information for ~3.5 million variants on the X chromosome. SNPs without rs identifier, SNPs in the pseudo-autosomal regions and SNPs with missing values were excluded. X-chromosomal SNPs were linkage disequilibrium pruned with Plink (Purcell et al., 2007) using the independent pairwise option with a sliding window of 50 SNPs and a threshold of R2=0.50 using Plink instruction plink—bfile JPTChrX—indep-pairwise 50 5 0.50—ld-xchr 1. The SNPs with small MAF have not been filtered out. This leaves a sample of 162225 SNPs from the whole X chromosome, that is the one that will be used in this subsection.

Figure 5 presents the model with the largest posterior probability for each one of these SNPs, presented in the order in which these SNPs appear on the X chromosome. The white band without SNPs between 58.1 MB and 63.0 Mb corresponds to the centromere. The presence of consecutive sequences of markers being systematically classified to the same disequilibrium scenario, or to one of the three disequilibrium scenarios, might be an indication of quality control problems in the SNP measurements, or might arise if the PAR region is erroneously included in the analysis. Too few SNPs being classified as being in HW equilibrium would also be an indication of either a problem in the measurements or of the fact that the population under scrutiny is actually in disequilibrium.

Model with the largest posterior probability, and hence the largest BF, for the SNPs selected from the Japanese population, presented in the position where they are placed on the X chromosome. The first panel corresponds to the sample of 162225 SNPs used in the ‘Simultaneous analysis of multiple X-chromosomal SNPs’ section, and the second one to the 1622 SNPs used in the ‘Multiple testing and the assessment of HW equilibrium’ section. The lower PAR zone is between 60001 and 2699520, and the upper PAR zone between 154931044 and 155260560; no SNPs in these zones were included in the analysis.

Model 0, representing HW equilibrium, is the one with the largest posterior probability in 95.27% of all the 162225 SNPs considered, Model 1 is the one with the largest probability in 1.89% of the cases, Model 2 is the one with the largest probability in 2.13% of the cases and Model 3 is the one with the largest probability in 0.71% of the cases. It is known that for SNPs with low MAF, which are abundant in this set of 162225 SNPs, power to detect disequilibrium is low. When one filters out the SNPs with MAF<0.05, one is left with only 52008 SNPs, and the proportion classified as being in equilibrium falls down to 89.08%.

The next subsection illustrates how one can assess whether the overall proportions obtained for all 162225 SNPs are compatible with the HW equilibrium model, M0, holding true, in a way that takes into account the multiple testing effect involved.

Multiple testing and the assessment of HW equilibrium

Carrying out the test for HW equilibrium based on the simultaneous analysis of multiple SNPs involves dealing with the multiple testing effect, which requires one to account for the experiment-wise error rate. In the Bayesian context, one approach to that problem is through the use of the false discovery rate and q-values, as described in Storey (2002, 2003, Muller et al. (2006), de Villemereuil et al. (2014) and de Villemereuil and Gaggiotti (2015).

Instead of using the false discovery rate, here a novel approach to address multiple testing in the Bayesian setting is used. The alternative method uses posterior predictive checks to assess whether the proportion of SNPs in the sample of 162225 of the previous section classified to each one of the four different scenarios is consistent with the proportions that would be obtained if the HW equilibrium was actually in place for the population. To estimate the proportions classified under each scenario in a population of SNPs actually in HW equilibrium, simulation from the posterior predictive distribution under M0 is used. For a description of the use of posterior predictive checks as a tool to validate models in general, see Chapter 6 of Gelman et al. (2014) or Puig and Ginebra (2014).

To do this simulation exercise, one needs to resort to a sample of SNPs that is smaller than the one used in the previous section, because we need to assume approximate independence between SNPs and because, at this point, the simulation exercise that would need to be done with the larger set of SNPs would take too long. That is why a random subsample of only 1622 SNPs is obtained from the 162225 SNPs used in the previous section to carry out the posterior predictive checks.

It turns that for the subsample with only 1% of all the SNPs previously used, Model 0 is the one with the largest posterior probability in 95.25% of the SNPs, Model 1 is the one with the largest probability in 2.03% of the cases, Model 2 is the one with the largest probability in 2.03% of the cases and Model 3 is the one with the largest probability in 0.68% of the cases. The second panel in Figure 5 presents the model with the largest probability for each one of these 1622 SNPs.

To assess whether these observed proportions of SNPs being classified as following each one of the models are compatible with the assumption that HW equilibrium is in place, we estimate the posterior predictive distribution and the posterior predictive credible intervals for these four proportions, assuming that the HW equilibrium holds and that the SNPs are independent. This last assumption will be satisfied due to the way in which the smaller subset of only 1622 SNPs was selected from the whole set of SNPs of the X chromosome.

The posterior predictive distribution can be estimated by repeatedly simulating 1622 × 5 tables of ‘data like the one from the Japanese study’ used to test for HW equilibrium, by using the posterior predictive distribution of the data under Model 0. For each one of the simulated tables, one then classifies the 1622 simulated SNPs to one of the four scenarios, based on their P(Mi|y) and finds the proportion of SNPs classified into each scenario.

Each one of the tables can be simulated from the posterior predictive distribution by:

-

1)

Simulating 1622 values for pAf, one value of each row of the table, using its posterior distribution under Model 0 which, assuming Beta(b1,0, b2,0) to be the prior, is:

which is also the posterior for pAm because under M0, pAm=pAf.

-

2)

For each value of pAm one simulates the nAm for that row from a Binomial(nm, pAm), one computes nBm=nm−nAm, and one simulates (nAAf, nABf, nBBf) for that row from a Multinomial

.

. -

3)

For each row of each table one computes P(Mi|y) for i=0,1,2,3, and for each simulated table one obtains the proportions of SNPs classified as following each one of the four Mi’s based on the largest P(Mi|y) for that row.

By repeating this exercise as many times as tables of data one intends to simulate, one obtains the posterior predictive distribution for the proportions of SNPs being classified as Mi for i=0,1,2,3, conditioned on the HW equilibrium model, M0, being the correct one. The rows of the new tables are simulated to be independent, which is a realistic assumption when one is analyzing a subset of approximately independent SNPs the way it is done here.

We have carried out this simulation exercise for the subset of 1622 SNPs selected from the Japanese population study by simulating 1000 tables from its posterior predictive distribution. It turns that if the HW equilibrium is in place, the 90% central posterior predictive credible interval for the proportion of SNPs classified as following M0 because their P(M0|y) is the largest is (94.6, 96.4), the 90% credible interval for the proportion of SNPs classified as following M1 because P(M1|y) is the largest is (1.4, 2.3), the one for the proportion of SNPs classified as following M2 is (1.8, 3.0) and the one for the proportion of SNPs classified as following M3 is (0.1, 0.5).

Note that the proportion of SNPs being classified into each one of these four models for the subset of markers from the Japanese population Genome project, which are 95.25, 2.03, 2.03 and 0.68% for M0, M1, M2 and M3, fall either well within these four posterior predictive credible intervals, or very close to it in the case of M3. The fact that the observed percentages fall within the posterior predictive intervals generated under the HWE assumption, suggests that the X-chromosomal markers without missing values of the LD-pruned database are in equilibrium, with only a slight excess of markers in scenario M3. By using posterior predictive checks involving all 1622 SNPs at once, instead of doing it one SNP at a time, one already takes into account the experiment-wise error rate, and one does not have to correct for the fact that one carries out multiple tests.

When one does the same exercise on data from populations that are not in HW equilibrium, the proportion of SNPs that are classified as following M0 falls, and some of the other three proportions increase, and they would fall outside of the posterior predictive intervals for these four proportions obtained assuming that the HW equilibrium model was in place. Given that the sample size here is a lot larger than the effective sample size assumed by the priors, carrying out a sensitivity analysis that considers alternative priors of similar effective sample size leads to results which are almost identical to the ones reported here.

Discussion

We have developed a Bayesian method for inference on HW equilibrium for biallelic markers at the X chromosome. Disequilibrium at the X chromosome may be due to a difference in allele frequencies between the sexes, or to females not corresponding to HW proportions or both these factors simultaneously. By computing the posterior probability for each scenario, geneticists can immediately infer the most likely scenario. A similar approach can also be used for the Bayesian analysis of autosomal variants.

The X-chromosomal exact test chooses between HW equilibrium, (that is, Model 0), and disequilibrium, (that is, Models 1, 2 and 3). In order to precisely determine the disequilibrium scenario with a frequentist approach, several statistical tests are necessary: an exact test with and without males and eventually an exact test for equality of male and female allele frequencies. Instead, by assigning a posterior probability to each one of the four scenarios, with the four probabilities adding up to one, our Bayesian approach provides a simple way of selecting the most probable scenario in the light of the data.

One of the advantages of the Bayesian approach to HW equilibrium testing of X-chromosomal markers is that, on top of yielding posterior probabilities for each one of the four scenarios, it also provides the posterior distribution of the parameters of interest. In Appendix 2, one can find details on that distribution.

Among all the marginal posterior distributions, the one for (f,d) is particularly useful because it helps one assess the degree of departure from HW equilibrium beyond computing the corresponding four posterior probabilities.

For our Bayesian analysis, we have found it convenient to parametrize disequilibrium by using the inbreeding coefficient and the ratio of male to female allele frequencies, using a Dirichlet prior on the genotype frequencies. Alternatively, other disequilibrium measures with priors specified directly on the disequilibrium measures might also be considered.

One side contribution of this manuscript is the suggestion to use posterior predictive checks to deal with multiple testing in the Bayesian framework, as described in the previous section.

From a computational point of view, the χ2-test for HWE of X-chromosomal markers is very fast, and it is feasible to do this for a complete X chromosome with 3.5 million markers. An exact test is computationally more demanding due to the presence of factorial calculations and enumeration of possible outcomes. The Bayesian procedures outlined in this paper do not require a markov chain monte carlo implementation as it is usual in most Bayesian applications these days, and that simplifies the computation a lot. If the integration required for the computation of the posterior probability of M1 is carried out efficiently, there should not be any problem in using the proposed method for a whole X chromosome.

Further computational savings could be attained by using the fact that many of the 3.5 million markers on the X chromosome are rare variants with a low minor allele frequency, and therefore the set of genotype counts will be identical for many SNPs. For markers with identical counts, the HW tests only have to be computed once.

Software

The Bayesian X-chromosomal procedures described in this paper have been programmed in R (R Core Team, 2017) by Xavi Puig, and are made available in version 1.5.8 of the Hardy–Weinberg package (Graffelman, 2015).

References

Ayres KL, Balding DJ . (1998). Measuring departures from Hardy-Weinberg: a Markov chain monte carlo method for estimating the inbreeding coefficient. Heredity 80: 769–777.

Berger JO, Bernardo JM, Sun D . (2015). Overall objective priors. Bayesian Anal 10: 189–221.

Bernardo J, Tomazella V . (2010). Bayesian reference analysis of the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In Chen MH, Dey DK, Muller P, Sun D, Ye K (eds). Frontiers of Statistical Decision Making and Bayesian Analysis, In Honor of James O. Berger. Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA, pp 31–43.

Consonni G, Gutierrez-Pena E, Veronese P . (2008). Compatible priors for Bayesian model comparison with an application to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium model. Test 17: 585–605.

Crow JF, Kimura M . (1970) An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. Harper & Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA.

Foll M, Gaggiotti O . (2008). A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics 180: 977–993.

Gautier M . (2014). Using genotyping data to assign markers to their chromosome type and to infer the sex of individuals: a Bayesian model-based classifier. Mol Ecol Resour 14: 1141–1159.

Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB . (2014) Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd Ed. Chapman and Hall: Boca Raton.

Graffelman J . (2015). Exploring diallelic genetic markers: the Hardy-Weinberg package. J Stat Softw 64: 1–23.

Graffelman J, Weir BS . (2016). Testing for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium at biallelic genetic markers on the X chromosome. Heredity 116: 558–568.

Graves JA, Wakefield MJ, Toder R . (1998). The origin and evolution of the pseudoautosomal regions of human sex chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet 7: 1991–1996.

Hamilton MB . (2009) Population Genetics. Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ. Wiley-Blackwell.

Hartl DL . (1980) Principles of Population Genetics. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA.

Hein J, Schierup MK, Wiuf C . (2005) Gene Genealogies, Variation and Evolution. Oxford University Press: Oxford: New York, NY, USA.

Li CC . (1976) The First Course in Population Genetics. The Boxwood Press: Pacific Groove, CA, USA.

Lindley D . (1988). Statistical inference concerning Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In Bernardo J, DeGroot M, Lindley, D, Smith A (eds). Bayesian Statistics 3. Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp 307–320.

Morita S, Thall PF, Muller P . (2008). Determining the effective sample size of a parametric prior. Biometrics 64: 595–602.

Muller P, Parmigiani P, Rice K . (2006). FDR and Bayesian multiple comparison rules. Johns Hopkins University, Department of Statistics Working Papers 115.

Pereira C, Rogatko A . (1984). The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium under a Bayesian perspective. Rev Bras Genet 4: 689–707.

Puig X, Ginebra J . (2014). A Bayesian cluster analysis of election results. J Appl Stat 41: 73–94.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D et al. (2007). PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 81: 559–575.

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

Shoemaker J, Painter I, Weir B . (1998). A Bayesian characterization of Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium. Genetics 149: 2079–2088.

Storey JD . (2002). A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc B 64: 479–498.

Storey JD . (2003). The positive false discovery rate. A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Ann Stat 31: 2013–2035.

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Altshuler D The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Auton A The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Brooks LD The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Durbin RM et al. (2010). A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467: 1061–1073.

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Auton A The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Brooks LD The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Durbin RM The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Garrison EP The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Kang HM et al. (2015). A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526: 68–74.

de Villemereuil P, Frichot E, Bazin E, François O, Gaggiotti OE . (2014). Genome scan methods against more complex models: when and how much should we trust them? Mol Ecol 23: 2006–2019.

de Villemereuil P, Gaggiotti OE . (2015). A new F ST-based method to uncover local adaptation using environmental variables. Methods Ecol Evol 6: 1248–1258.

Wakefield J . (2009). Bayes factors for genome-wide association studies: Comparison with p-values. Genet Epidemiol 33: 79–86.

Wakefield J . (2010). Bayesian methods for examining Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Biometrics 66: 257–265.

Wise AL, Gyi L, Manolio TA . (2013). eXclusion: toward integrating the X chromosome in genome-wide association analyses. Am J Hum Genet 92: 643–647.

You XP, Zou QL, Li JL, Zhou JY . (2015). Likelihood ratio test for excess homozygosity at marker loci on X chromosome. PLoS One 10: e0145032.

Zheng G, Joo J, Zhang C, Geller NL . (2007). Testing association for markers on the X chromosome. Genet Epidemiol 31: 834–843.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Grant 2014SGR551 from the Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) of the Generalitat de Catalunya, by Grants MTM2015-65016-C2-2-R (MINECO/FEDER) and MTM2013-43992-R of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the European Regional Development Fund, and by Grant R01 GM075091 from the United States National Institutes of Health. The authors are extremely grateful for the comments and suggestions for improvement of the associate editor and two referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Marginal likelihoods

Here we present the marginal likelihoods, P(y|Mi) for i=0,…,3, needed to compute the posterior probabilities, P(Mi|y), through equation (3.2). The priors assumed are the ones described in ‘Choice of a prior distribution’ section, and y=(nAAf, nABf, nBBf, nAm, nBm).

The marginal likelihood under Model 0, under HW equilibrium, is:

The marginal likelihood under Model 1, with d=1 and f≠0, can be computed through:

The marginal likelihood under Model 2, with d≠1 and f=0, is:

Finally, the marginal likelihood under the saturated Model 3 is:

Note that the only model that requires integration is Model 1. However, it can be carried out numerically without any problem because the integration region is compact, and grid size can be set to be as small as needed for the precision required.

Appendix 2

Posterior distribution under Model 3

Under the saturated Model 3, (nAAf, nABf, nBBf) has the Multinomial(nf,(pAAf, pABf, pBBf)) distribution and nAm has the Binomial(nm, pAm) distribution. Under the assumption that a priori (pAAf, pABf, pBBf) is Dirichlet(a1,3,f, a2,3,f, a3,3,f), and pAm is Beta(b1,3,m, b2,3,m), the posterior distribution for (pAAf, pABf, pBBf) is:

independent of the posterior distribution for pAm, which is:

The marginal posterior distributions for pAf, f and d follow from the ones for (pAAf,pABf,pBBf) and for pAm, and they can be easily estimated by simulating large samples of (pAAf,pABf,pBBf), and of (pAm,pBm), and for each value in the sample compute the corresponding value of pAf, of f, and of d, using equations (2.6),(2.4) and (2.5), respectively.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Puig, X., Ginebra, J. & Graffelman, J. A Bayesian test for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of biallelic X-chromosomal markers. Heredity 119, 226–236 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2017.30

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2017.30

This article is cited by

-

A measure of evidence based on the likelihood-ratio statistics

Statistical Papers (2022)

-

A test for deviations from expected genotype frequencies on the X chromosome for sex-biased admixed populations

Heredity (2019)

-

Bayesian model selection for the study of Hardy–Weinberg proportions and homogeneity of gender allele frequencies

Heredity (2019)

.

.