Abstract

Recent episodes of mass mortalities in the Mediterranean Sea have been reported for the closely related marine sponges Ircinia fasciculata and Ircinia variabilis that live in sympatry. In this context, the assessment of the genetic diversity, bottlenecks and connectivity of these sponges has become urgent in order to evaluate the potential effects of mass mortalities on their latitudinal range. Our study aims to establish (1) the genetic structure, connectivity and signs of bottlenecks across the populations of I. fasciculata and (2) the hybridization levels between I. fasciculata and I. variabilis. To accomplish the first objective, 194 individuals of I. fasciculata from 12 locations across the Mediterranean were genotyped at 14 microsatellite loci. For the second objective, mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I sequences of 16 individuals from both species were analyzed along with genotypes at 12 microsatellite loci of 40 individuals coexisting in 3 Mediterranean populations. We detected strong genetic structure along the Mediterranean for I. fasciculata, with high levels of inbreeding in all locations and bottleneck signs in most locations. Oceanographic barriers like the Almeria-Oran front, North-Balearic front and the Ligurian-Thyrrenian barrier seem to be impeding gene flow for I. fasciculata, adding population divergence to the pattern of isolation by distance derived from the low dispersal abilities of sponge larvae. Hybridization between both species occurred in some populations that might be increasing genetic diversity and somewhat palliating the genetic loss caused by population decimation in I. fasciculata.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decades, massive mortalities of marine invertebrates have been reported in all oceans and seas, caused by a variety of factors from contaminants to thermal-related diseases, and seriously threaten the biodiversity of the areas where they occurred (Pérez et al., 2000; Laboy-Nieves et al., 2001; Sala and Knowlton, 2006; Webster, 2007; Garrabou et al., 2009). From a genetic point of view, massive mortality events usually produce bottlenecks (dramatic reductions of the effective population size), loss of rare alleles and thus an overall reduction in genetic diversity. Over time, the strong effect of genetic shift on reduced populations can ultimately drive populations to inbreeding depression (Frankham, 2005; Hauser and Carvalho, 2008). Eventually, if genetic diversity remains low and inbreeding increases, detrimental effects will be observed in the affected population and the overall species fitness (Hauser and Carvalho, 2008; Frankham, 2010). In addition, the reduction of genetic diversity is predicted to decrease species resilience to environmental stressors or perturbations and reduce their adaptive evolutionary potential (Spielman et al., 2004; Frankham, 2005). In this sense, the assessment of genetic diversity and structure, connectivity and inbreeding of the affected species is key to estimating the effects of environmental perturbations (for example, thermal stress), disease outbreaks and mass mortalities on population demographics, and hence their potential for recovery.

Sponges are among the most simple and primitive metazoans, yet they have various biological and ecological properties that make them an influential component of marine ecosystems. Marine sponges provide refuge for many small invertebrates and are critical to benthic–pelagic coupling across a wide range of habitats (see, for example, Ilan et al., 1994). In some ecosystems, sponges show an abundance and diversity of species that can comprise most of the living mass (see, for example, Diaz and Rützler, 2001; McClintock et al., 2005). In addition, they have essential roles in the biogeochemical cycle of silica (Maldonado et al., 2010a) and dissolved organic matter (de Goeij et al., 2013). Unfortunately, like many other marine invertebrates, sponges are currently threatened by numerous environmental perturbations caused by global climate change, especially in near-shore ecosystems (Hughes et al., 2003; Garrabou et al., 2009; Webster et al., 2013; Pérez and Vacelet, 2014). The vulnerability of these ecosystems is increased by higher harvesting rates of economically important species, human recreational activities and coastal development, terrestrial runoff and the presence of heavy metals and pollutants in harbors and marinas (Commendatore et al., 2000). Sessile invertebrates, like sponges, are also particularly susceptible to temperature anomalies and continuous exposure to waterborne pathogens and pollutants because of their immobility (see, for example, Cebrian et al., 2006; Garrabou et al., 2009).

Reports of sponge disease have increased dramatically in recent years, with sponge populations decimated at some sites in the Mediterranean and Caribbean (see Webster, 2007 for a review). In particular, Mediterranean and Adriatic dictyoceratids (especially Ircinia spp.) have been consistently reported as affected by episodes of mass mortalities since the 1990s (see, for example, Garrabou et al., 2009; Maldonado et al., 2010b; Cebrian et al., 2011; Stabili et al., 2012). Three species of the genus Ircinia are widely distributed in the Mediterranean Sea, with populations occurring in shallow rocky coasts: Ircinia fasciculata, Ircinia variabilis and Ircinia oros. Ircinia species are aspiculate sponges, chemically diverse and harbor complex host-specific communities of bacterial and cyanobacterial symbionts (Erwin et al., 2012a,2012b; Pita et al., 2013). Both I. fasciculata and I. variabilis are affected by a disease-like condition (Stabili et al., 2012) reported by several authors in 2008 in the North and South Western Mediterranean Sea (Maldonado et al., 2010b; Cebrian et al., 2011). Whereas a monitored population of I. fasciculata in the southern coast of Spain (Granada) experienced 30% of mortality (Maldonado et al., 2010b), two monitored populations of I. fasciculata in Cabrera and Scandola Marine Reserves were decimated with ∼90% mortality (Cebrian et al., 2011). This disease-like condition, which was characterized by small round pustules that developed into large areas of necrotic tissue and eventually resulted in the death of the sponges, was linked to abnormally high seawater temperatures (>24 °C; Cebrian et al., 2011). Moreover, I. fasciculata disease probably resulted from a proliferation of several bacterial pathogens (Maldonado et al., 2010b). Given the large impact of the disease-like condition on some populations, Cebrian et al. (2011) predicted local extinctions of the species in the studied areas. In situations under environmental stress, extinction rates could also be increased substantially by high inbreeding levels that are predicted to decrease species resilience to environmental stressors and therefore reduce the adaptive evolutionary potential of the species (Spielman et al., 2004; Frankham, 2005). Thus, determining the genetic diversity and level of connectivity in sponge populations of this species is crucial when designing management strategies to prevent its extinction. Sponge populations are usually highly structured in ‘stable conditions’ (that is, healthy populations), with relatively low gene flow and high levels of inbreeding (see, for example, Duran et al., 2004; Dailianis et al., 2011; Chaves‐Fonnegra et al., 2015; Giles et al., 2015; Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015). Therefore, even in ‘stable conditions’ the recovery of sponge populations after massive reduction of the effective population size can be limited by their own biology, dispersal potential and oceanographic currents, and one could even predict lower recovery rates in stressed populations.

The two target species of the present study are I. fasciculata (Pallas, 1766) and I. variabilis (Schmidt, 1862). These species are phylogenetically closely related (see Erwin et al., 2012b) with an external appearance so similar and plastic that it can lead to uncertainties in identification, even though they are generally considered different species (Pronzato et al., 2004). From a morphological point of view, I. variabilis contains inorganic inclusions in its skeletal fibers, whereas I. fasciculata lacks such inclusions, prompting Pronzato et al. (2004) to transfer I. fasciculata to the genus Sarcotragus and rename the species, S. fasciculatus (Pallas, 1766). From a molecular point of view, a recent analysis using the nuclear ribosomal gene internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS-2) indicated that I. variabilis and I. fasciculata were indeed different but closely related species with a divergence of 2.97%±0.38 (Erwin et al., 2012b), even though analyses of mitochondrial sequences lacked enough resolution to differentiate among them. In light of these results, we decided to maintain the name I. fasciculata in this study until a thorough analysis is performed to solve its true generic status. Each species (I. variabilis and I. fasciculata) harbors several specific microbes within their symbiotic content (Erwin et al., 2012b), and interestingly, even though these species live in sympatry, they present slightly different habitat preferences and large differences in growth rates (Turon et al., 2013). In marine sperm broadcasters, even when species show large phylogenetic divergences, hybridization is relatively common in areas of secondary contact (see, for example, Bierne et al., 2003; Willis et al., 2006; Harper and Hart, 2007; Nydam and Harrison, 2011). In particular, hybridization/introgression among sponges has long been suspected and previously suggested in closely related species with sympatric distributions (Dailianis et al., 2011; Escobar et al., 2012). In this context, assessing the effect of potential hybridization on overall genetic diversity of both Ircinia species is fundamental to understanding their genetic structure and connectivity.

The main objectives of this study are twofold: (1) to describe the genetic structure of I. fasciculata across the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas in order to reveal connectivity patterns among populations and detect the potential effects of mass mortalities on the effective population size and (2) to identify whether hybridization occurs between I. fasciculata and I. variabilis and, if it does, to which extent.

Materials and methods

Sampling and DNA extraction

We collected ∼2 cm3 of tissue from 194 specimens of I. fasciculata of similar size (>500 cm3) between 2010 and 2013 in 12 locations across the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas (see details in Table 1). Similar sizes were selected in an effort to avoid sampling sponges from different cohorts or sponges that had recently been diseased (small fragments sometimes remained attached to the rock if the disease did not kill the whole sponge and could be confused with juveniles). Sampling was performed by SCUBA diving within the first 10 m of each location. Only six healthy individuals were sampled from Scandola Marine Reserve (Table 1) given the extreme decimation this population experienced from 2008 to 2010 (Cebrian et al., 2011). Variation in geographical distance ranged from 21 to 3006 km for the studied area. Sponge fragments were preserved in absolute ethanol that was replaced with fresh ethanol at least three times within 48 h and stored at −20 °C until further processed. DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions with a minor modification concerning overall cell lysis time (that is, incubation was conducted overnight) and the final DNA elution step (performed twice using 50 μl of buffer EB each time).

Microsatellite amplification and analysis

We genotyped all individuals of I. fasciculata from all locations at 14 microsatellite loci (3IFAS, 7IFAS, 8IFAS, 10IFAS, 22IFAS, 25IFAS, 36IFAS, 40IFAS, 41IFAS, 42IFAS, 44IFAS, 47IFAS, 48IFAS and 49IFAS) previously described elsewhere (Riesgo et al., 2014), using the PCR conditions described therein. The sizes of the fluorescently labeled PCR products were estimated using an internal size marker (GeneScan 500 LIZ, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequencer (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed with PeakScanner v1.0.

Genetic diversity in I. fasciculata populations

Estimations for the observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity, and the fixation index (FIS), commonly used as an inbreeding coefficient, were performed using GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse, 2006). We used Genepop web version 4.0.10 (Raymond and Rousset, 1995) to obtain values for departure of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) by locus and population (sampling site) using a probability test with level of significance determined by the following Markov chain parameters: 5000 dememorization steps, 1000 batches and 5000 iterations per batch. The total number of alleles per locus and population, allele richness, number of private alleles and genetic (gene) diversity (expected frequency of heterozygotes within subpopulations, including a correction for sampling bias stemming from sampling a limited number of individuals per population) were calculated with GENODIVE (Meirmans and Van Tienderen, 2004) and FSTAT 2.9.3.2 (Goudet, 1995). Tests for linkage disequilibrium for each locus were previously performed elsewhere (Riesgo et al., 2014).

Population differentiation in I. fasciculata

We performed six different methods to assess population structure and differentiation in I. fasciculata. Four methods were based on distances: FST estimations, isolation by distance (IBD), BARRIER analyses and the analysis of the molecular variance (AMOVA), and two used a clustering approach: STRUCTURE and the discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC). Given that the distance methods for measuring population dissimilarity are largely affected by the violation of the HWE (Waples, 2015), we removed five loci from the final data matrix that displayed clear HWE deviation in more than half of the analyzed locations (3IFAS, 10IFAS, 8IFAS, 47IFAS and 49IFAS; see Riesgo et al., 2014). Thus, all distance-based analyses were computed on a subset of data with the remaining nine microsatellites that did not show deviation from the HWE.

We first assessed the occurrence of population subdivision in large clusters using a Bayesian clustering approach in STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000), a software that assigns individuals to clusters probabilistically, under an admixture model and with allele frequencies correlated between samples. The program was run with a burn-in time of 50 000 repetitions and 150 000 iterations (Markov chain Monte Carlo), setting the putative K (predicted number of populations) from 1 to 15 and 10 replicates for each run. The estimation of log probabilities of data Pr(X|K) for each value of K was evaluated by calculating ΔK that accounts for the rate of change in the log probability of data between successive K values (Evanno et al., 2005). ΔK is currently considered a more reliable predictor of the true number of populations (Evanno et al., 2005). Calculations and evaluation of ΔK were performed with Structure Harvester (Pritchard et al., 2000) and graphs were visualized in STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000). The CLUMPAK web server (Kopelman et al., 2015) was then used to find the best alignment of the results from STRUCTURE across the range of K values by averaging the probabilities of each K cluster, enabling the production of a figure with the entire range of K values.

Population differentiation was estimated with FST statistic between pairwise sampling sites using an infinite allele model and the software Arlequin (Excoffier et al., 2005). We only calculated the FST statistic and not RST because the former performs better when sample size is <50 individuals per site or <20 loci are analyzed (Gaggiotti et al., 1999). Significance of FST values was evaluated by performing 20 000 permutations in Arlequin and corrected based on the false discovery rate approach described in Narum (2006). The frequency of null alleles was estimated using the expectation maximization algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) in FreeNA (Chapuis and Estoup, 2007). As the presence of null alleles in well-differentiated populations is known to yield an overestimation of population differentiation (Chapuis and Estoup, 2007), we repeated our analysis Excluding Null Alleles (Chapuis and Estoup, 2007). In all cases, the corrections only affected the fourth or fifth decimal place in the FST value and consequently the effect of presence of null alleles was disregarded.

To determine the spatial patterns driving differentiation among populations, linearized pairwise FST estimates (FST/1−FST) obtained for nine microsatellite loci (see above) were correlated against log-transformed geographical distances between samples and IBD using a Mantel test in Arlequin (Excoffier et al., 2005). Geographical distances were estimated as the minimum linear distance between pairs of locations by sea. We tested IBD for the whole data set, and also separately for a data set containing the locations on the Western Mediterranean (CAI, ESC, TOS, BLA, CAL and ALI) and the Pre-Balear island locations (CAB and COR), between which potential dispersal barriers exist (that is, oceanic currents). The effect of barriers in determining the genetic structure of I. fasciculata populations was further evaluated using pairwise FST values and visualized with the software BARRIER v2.2 (Manni et al., 2004). This method links a matrix of geographical coordinates with their corresponding distance matrix (FST), and applies the Monmonier’s maximum distance algorithm to identify ‘barriers’ to gene flow among sites, namely the zones where differences between pairs of sites are the largest.

We also performed DAPC with the adegenet package (Jombart, 2008) implemented in R (https://www.r-project.org/). DAPC defines clusters using the clustering algorithm k-means on transformed data with principal component analysis. The algorithm k-means is then run sequentially with increasing values of k, and different clustering solutions are compared using Bayesian information criterion. The optimal cluster solution should correspond then to the lowest value of Bayesian information criterion. We applied the DAPC analysis for both the complete matrix of all sampling sites and a reduced set containing only those from the Western Mediterranean (CAI, ESC, TOS, BLA, CAL and ALI) and the Pre-Balear island (CAB and COR) groups.

AMOVA was used to determine the hierarchical distribution of genetic variation. To run this analysis, we a priori defined five groups according to biogeographical areas previously defined by Spalding et al. (2007) and partially isolated by oceanographic fronts as found by Schunter et al. (2011) and Villamor et al. (2014): Alboran Sea, Western Mediterranean, Pre-Balear islands, Thyrrenian Sea and Adriatic sea (see Table 1). The significance of the AMOVAs was calculated with 16 000 permutations of the original data.

Population assignment and migration in I. fasciculata

In addition, we performed a population assignment analysis calculating the likelihood ratio thresholds for all 12 populations based on the Monte Carlo test with an α of 0.002 and 1000 replicated data sets using GENODIVE version 2.0b23 (Meirmans and Van Tienderen, 2004). This method assigns or excludes reference populations as possible origins of individuals on the basis of multilocus genotypes. Genetic assignment methods allow inferring where individuals originated, providing estimates of real-time dispersal through the detection of immigrant individuals. These analyses are useful in addressing relationships and structure when genetic differentiation at the population level is low. In addition, the detection of last-generation migrants was performed based on the calculations of the likelihood of an individual belonging to a given population that was then done replacing the zero frequencies by a random 0.005 frequency (estimated to outperform tests) in 4000 permutations in GENODIVE.

Demographic effects of mass mortalities in I. fasciculata

In order to detect recent effective population size reductions (bottlenecks) from allele data frequencies in our localities because of mass mortalities we used the software BOTTLENECK (Cornuet and Luikart, 1996). This program is based on the assumption that populations that have gone through a recent reduction of their effective population size show a reduction of the allelic diversity and heterozygosity, even though the allele frequencies are reduced faster than the heterozygosity. The software computes the distribution of the heterozygosity expected from the number of alleles for each population and locus, and it takes into account the sample size under the assumption of mutation–drift equilibrium using three different models: infinite allele model, two-phase model and the stepwise mutation model. The analysis is performed using three tests: a ‘sign test’, a ‘standardized differences test’ (Cornuet and Luikart, 1996) and ‘Wilcoxon sign-rank test’ (Luikart and Cornuet, 1998).

Phylogenetic relationships between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata

In order to shed light into the phylogenetic relationships between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata, we amplified a fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene, increasing the taxon sampling from only 3 specimens of I. fasciculata (Erwin et al., 2012b) to 15, and including all sequenced species of the family Irciniidae (see below). A fragment of 1093 bp of COI was amplified for 12 specimens of I. fasciculata from the most distant sites (CAL, n=1; ESC, n=2; TAR, n=1, TOS, n=2; NAP, n=4; CRO, n=2) using the primers dgLCO1490 (Meyer et al., 2005) and COX1-R1 (Rot et al., 2006). COI sequences of I. variabilis and I. fasciculata from BLA were obtained from GenBank (see accession numbers in Figure 1a). Reactions were performed using 0.5 μl of total DNA (∼0.5–1 ng of DNA), 5.1 μl of pure distilled water, 3.3 μl of Extract-N-Amp PCR Reaction Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.3 μl of each primer (10 μM). The amplification program was as follows: denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 45 °C for 60 s and extension at 72 °C for 60 s; with a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were purified and sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA), an annealing temperature of 50 °C and using the same primers as for the amplification step. Samples were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl Genetic Analyzer available at the University of Barcelona Scientific and Technological Centers. Sequences were edited using Geneious 8.0 (Kearse et al., 2012) and aligned with MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002). The sequence data obtained in this study have been deposited in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) GenBank database (accession numbers in progress). Additional sequences of species from the family Irciniidae were obtained from GenBank: I. oros (JN655186, JN655189), I. strobilina (JX306089), I. felix (JX306085), I. ramodigitata (FN552859), I. irregularis (FN552858), Ircinia sp. (LN828727), Sarcotragus spinulosus (HG816026, HG816027, HE591460), Psammocinia bulbosa (FN552812) and Psammocinia sp. (FN552837, FN552855). We included as outgroups Spongia officinalis (HQ830364) and Strepsichordaia sp. (FN552875) that are also members of the order Dictyoceratida, but not from the family Irciniidae.

Assignment of individual genotypes of I. fasciculata to genetically similar clusters (K) as inferred by STRUCTURE for all studied locations with (a) K=2 and (b) K=5. (c) Pie frequency charts showing percentage of populations assigned to each of the five clusters represented in (b) for all locations. Gray color is applied to the percentage of individuals that were assigned to more than one cluster. Pre-Bal, Pre-Balear islands; Thyrre, Thyrrenian Sea; Adria, Adriatic Sea. A full color version of this figure is available at the Heredity journal online.

The evolutionary model that best fitted our data was obtained with jModeltest2 (Darriba et al., 2012), and evaluated using the Akaike information criterion. The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using maximum likelihood in PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003) with 500 bootstrap replicates, 10 initial trees and the evolutionary model HKY85 (see above). Bayesian inference analysis was performed in MrBayes v3.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) with two runs, each with three hot chains and one cold chain with 20 million generations, sampling every 2500th generation, using random starting trees. The remaining trees were combined to find the maximum a posteriori probability estimate of phylogeny. This analysis was conducted twice and convergence was tested using Tracer v1.5 (Rambaut and Drummond, 2007). The relationships among the COI sequence haplotypes of both I. fasciculata and I. variabilis were inferred using the TCS method in the program TCS (Clement et al., 2000) as implemented in Popart 1.7 (http://popart.otago.ac.nz).

Hybridization between I variabilis and I. fasciculata: microsatellite analyses

We performed a fine-scale analysis of the introgression processes between our two target Ircinia species by genotyping 14 individuals from Tossa de Mar, Corsica and Cabrera of I. variabilis (TOS: n=5, COR: n=6 and CAB: n=3, respectively), and randomly selected 36 individuals from the same sampling sites of I. fasciculata that were already genotyped (TOS: n=10, COR: n=6, and CAB: n=10) using 12 microsatellite loci (all listed above except for 7IFAS and 40IFAS, as we were not able to amplify them in I. variabilis). We subsampled TOS and CAB for I. fasciculata in order to maintain the population sizes as even as possible, given that unbalanced sample sizes could hamper the recovery of population structure (Puechmaille, 2016). These three localities (TOS, COR and CAB) were selected because both species live in sympatry. Hybrid detection was achieved by performing an individual assignment to each cluster using STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al., 2000), running the program with a burn-in time of 50 000 repetitions and 150 000 iterations (Markov chain Monte Carlo), and setting the putative K (predicted number of genetic units) from 1 to 6, with 10 replicates for each K. The estimation of log probabilities of data and evaluation of ΔK were calculated as described above. We then used CLUMPACK (Kopelman et al., 2015) to find the best alignment of the results across the range of K values. Genetic differentiation between species and sites was visualized with a DAPC and the adegenet package (Jombart, 2008) implemented in R.

Results

Population structure and connectivity of I. fasciculata

None of the 194 individuals analyzed showed identical genotypes, and therefore clonality can be regarded as negligible in the studied populations. The total number of alleles ranged from 2 to 17 per population, and the average number of alleles per population ranged from 3.857 (COR) to 8.000 (CRO) (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, the average frequency of private alleles differed from 0.143 (COR) to 1.500 (CRO). Private alleles were present in all populations varying from 1 (ALI, average pA frequency=0.429) to a maximum of 4 in CRO (average pA frequency=1.5; Table 2).

Genetic (gene) diversity values were very similar across populations, ranging from 0.626 in TOS to 0.728 in CAL (Supplementary Table 1). Expected heterozygosity values (He) showed the same trend as the genetic diversity values in all populations when using all 14 loci and the subset of 9 loci (Table 2). When the matrix containing all 14 loci was analyzed, fixation indexes (FIS) were positive in all cases except for CAI and TOS. When considering the 14 microsatellite markers, all populations except for BLA, COR and CRO deviated from HWE, whereas with the 9 microsatellites subset all populations remained in HWE (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Population differentiation in I. fasciculata

The optimal number of clusters for the whole data set by the method of Evanno et al. (2005) in the Bayesian analysis with STRUCTURE was two genetically homogenous groups (K=2) being followed by five (K=5; Figures 1a and b; Supplementary Figure 1). Results for K=2 revealed the division into two differentiated clusters without a clear pattern of subdivision: one cluster corresponded to the populations TAR and GRA (Alboran Sea), as well as some individuals from CAL, CAB, CAL, CAB, NAP and CRO (Table 1), and another cluster containing most individuals sampled from Western Mediterranean locations (CAI, ESC, TOS, BLA, CAL and ALI) and the Pre-Balear island locations (CAB and COR; Figure 1a). When the number of clusters K was selected by the highest likelihood (K=5; Supplementary Figure 1) the populations revealed inner substructuring (Figures 1b and c): (1) the first group (green) was formed mostly by specimens from the east Mediterranean and half of the individuals of NAP, and CAL populations; (2) the second group (yellow) was formed by several individuals from three different geographical areas, half of the populations of TAR, TOS, NAP and CRO; (3) the third group (pink) was formed by half population of TAR, the entire GRA population and some individuals in NAP; (4) the fourth group (blue) comprised CAI, BLA, COR and half of the populations of ESC, TOS, CAL and CAB; and finally (5) the fifth group (red) comprised half ESC and CAB populations (Figures 1b and c). It is noteworthy that in most populations individual genotypes were assigned to a specific cluster, and ‘mixed’ genotypes from different clusters were detected at low frequency.

FST pairwise comparisons using 9 loci were always significant (Supplementary Table 2), except for comparisons between CAI and ESC (FST=0.01905), ESC and ALI (FST=0.06504), TAR and CAB (FST=0.00336) and ESC and CRO (FST=0.01581), indicating significant differentiation in the genetic structure among most of the studied populations.

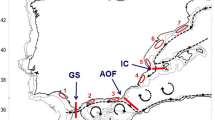

The Mantel tests (Figure 2) revealed IBD only when the Western Mediterranean and the Pre-Balear island locations were analyzed separately (Figure 2b), but it was not significant when all populations were analyzed together (Figure 2a). Indeed, several barriers, which could potentially be oceanographic, were detected and appeared to contribute to population differentiation more than distance (Figure 3a). In our case, three barriers were set a priori given the three major oceanographic waterfronts known in the Mediterranean (Figure 3b). The Monmonier’s maximum distance algorithm detected these three barriers and denoted their rank of importance (Figure 3a): first the Almeria-Oran Front (a) separating the Alboran Sea (TAR and GRA) locations from the rest, then the Ligurian-Thyrrenian barrier (b) separating Thyrrenian and Adriatic locations (NAP and CRO) from the western ones, and finally the North-Balearic Front (c) that also separated BLA and CAL from the rest of the West Mediterranean populations.

Detection of barriers to gene flow in I. fasciculata across the Mediterranean Sea. (a) Barriers detected by software BARRIER ranked a to c in order of magnitude. (b) Map of the Mediterranean seawater circulation indicating major fronts and oceanographic barriers previously known in the Mediterranean. Note that sampling locations for I. fasciculata are indicated in the map.

The DAPC showed separation between the Alboran Sea (TAR and GRA), the Pre-Balear islands (COR and CAB), the Thyrrenian and Adriatic locations (NAP and CRO) and the remaining locations of the Western Mediterranean (Figure 4a). Indeed, the northern locations of the Western Mediterranean (CAI and ESC) and the Pre-Balear islands (COR and CAB) grouped more closely together, being slightly separated from the rest of populations of the Western Mediterranean and Thyrrenian and Adriatic Sea group (Figure 4a). In addition, when analyzing the spatial structure of Western Mediterranean and Pre-Balear island locations, only CAL was clearly separated from the rest of populations (Figure 4b).

When analyzing population differentiation in the different regions using AMOVA, we found significant genetic differentiation among the groups containing Alboran Sea, Western Mediterranean, Pre-Balear islands and Thyrrenian and Adriatic Sea locations (Tables 1 and 3). In addition, significant genetic differentiation among the populations within these groups was also observed (Table 3).

Population assignment and migration in I. fasciculata

The population assignment analysis showed large genetic exchange within each of the groups (Alboran Sea, Western Mediterranean, Pre-Balear islands, Thyrrenian and Adriatic Seas), with few contributions outside the groups, except for CAI and BLA that seemed to have contributed genotypes to almost all locations in the sampled region (Figure 5a). The analysis only detected 5 migrants from the last generation, 1 individual from GRA comprising 15% of NAP, 1 individual from ESC comprising 16.7% of COR, 1 individual from CAL and another from CRO being 20% of ALI and finally 1 individual from TAR contributing to 5% of GRA (Figure 5b).

Population assignment of individuals and last-generation migrants in I. fasciculata. (a) Number of individuals assigned to each population for all sampling locations. (b) Number of last-generation migrants (indicated in percentage of population). The original location of migrants (origin) is color coded following the same scheme as in DAPC of Figure 4a. A full color version of this figure is available at the Heredity journal online.

Demographic effects of mass mortalities in Ircinia fasciculata

All three BOTTLENECK tests identified a population reduction in COR under the infinite allele model (Table 4), but also detected population reductions in other locations depending on the model used. Using two-phase model, the sign test did not identify any bottleneck in any of the studied locations using the Wilcoxon rank test (Table 4), whereas the standardized differences test identified an effective size reduction in BLA, TOS, TAR, GRA, NAP and CRO with the same model (Table 4). Using the stepwise mutation model, the standardized differences test identified effective size reductions in most sites except for COR (Table 4), even though using the same model, the Wilcoxon rank test identified bottlenecks in CAB, BLA, ESC, TAR, NAP and CRO (Table 4).

Phylogenetic relationship between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata

The 19 sequences of the COI marker analyzed from 8 different locations of I. variabilis and I. fasciculata were 1093 base pairs long and, among them, 28 sites showed polymorphism (5.004%). Within the reduced phylogeny of the genus Ircinia, both the maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference analyses showed a large, well-supported clade containing sequences of both I. variabilis and I. fasciculata (Figure 6a). Within this clade, sequences showed no clear grouping pattern between species or among locations (Figure 6a). The TCS haplotype network showed that the main haplotype for I. fasciculata was recovered in three locations (BLA, CAL and NAP) and this same haplotype was shared with three individuals of I. variabilis from BLA (Figure 6b). In addition, seven more haplotypes were recovered for I. fasciculata (Figure 6b).

Hybridization patterns in I. variabilis and I. fasciculata. (a) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic phylogeny based on the COI sequences from the genus Ircinia with bootstrap values (above nodes) and posterior probabilities (below nodes) mapped on shared clades between maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference analyses. Support values over 70 are located over each node. Sequences obtained in this study appear in bold letters. The abbreviations for sampling sites can be found in Table 1. (b) TCS haplotype network for I. fasciculata. (c) DAPC graphical representation of population differentiation in three locations (TOS, COR and CAB) containing both species (I. variabilis and I. fasciculata) using microsatellites. (d) STRUCTURE output of individual assignment to five clusters (K=5) in three locations (TOS, COR and CAB) containing both species (I. variabilis and I. fasciculata) using microsatellites.

Hybridization patterns in I. variabilis and I. fasciculata

The DAPC analysis using microsatellite data of both species collected in the same three sites showed a clear group containing all locations of I. variabilis (IVTOS, IVCAB and IVCOR) and those individuals of I. fasciculata collected in Tossa de Mar (IFTOS), whereas the rest of locations of I. fasciculata appeared separated from them (IFCAB and IFCOR, Figure 6c). In addition, the individual assignment analysis performed in STRUCTURE showed that individuals from the locations TOS and CAB of I. variabilis belonged to the same group (blue) as some individuals of I. fasciculata in the sites TOS, COR and CAB (Figure 6d). Similarly, two individuals in the location of COR of I. variabilis appeared as a ‘mixture’ of I. variabilis clusters (Figure 6d). The crimson cluster mostly belonged to individuals of I. fasciculata at the locations of TOS and CAB (Figure 6d). All our results indicate some degree of hybridization between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata, at least in some locations, and especially in TOS.

Discussion

Genetic diversity in I. fasciculata

Genetic diversity (calculated with the parameters gene diversity in GENODIVE and He in GenAlex) was ∼0.6, a value that is similar to those observed in other Mediterranean sponges, including Crambe crambe (∼0.6, Duran et al., 2004), the endangered species Spongia lamella (∼0.5, Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015), the bath sponge S. officinalis (∼0.8, Dailianis et al., 2011) and Scopalina lophyropoda (∼0.4; Blanquer and Uriz, 2010). Inbreeding analysis detected a significant heterozygosity deficit in most localities, indicating that they were not in HWE, a situation widespread among most studied sponges (Duran et al., 2004; Blanquer and Uriz, 2010; Dailianis et al., 2011; Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015; Chaves‐Fonnegra et al., 2015; Giles et al., 2015) and many other marine benthic invertebrates in the same geographical area (see, for example, Addison and Hart, 2005; Pérez-Portela and Turon, 2008; Mokhtar-Jamaï et al., 2013; Pérez-Portela et al., 2016). One of the reasons for deviations from HWE in marine invertebrates may be associated with the production of planktonic sperm for fertilization (Addison and Hart, 2005), the reproductive strategy of sponges (Maldonado and Riesgo, 2008). It has been suggested that in free spawners, higher mutation rates caused by larger numbers of cell cycles leading to high sperm production would be consistent with more frequent null alleles, causing greater departures from HWE in comparison with copulating species with lower allocation to sperm production (see Addison and Hart, 2005 for discussion). However, as our FreeNA analysis did not detect any significant effect of null alleles, other nonexclusive factors should be considered to explain heterozygote deficiencies, including high levels of inbreeding, selection against heterozygotes, Wahlund effect or a combination of all or some of these factors (Freeland et al., 2011). Inbreeding is indeed widespread in most benthic invertebrates with a lecithotrophic larva and very limited dispersal capabilities (see, for example, Goffredo et al., 2004; Mariani et al., 2006; Pérez-Portela and Turon, 2008; Ledoux et al., 2010; Mokhtar-Jamaï et al., 2013; Pérez-Portela et al., 2016). For instance, the mean distance between the parents and offspring in the red coral Corallium rubrum was estimated to be 20–35 cm (Ledoux et al., 2010), a similar value to that reported for the Mediterranean sponge C. crambe (Calderon et al., 2007). On the other hand, genetic substructuring within I. fasciculata populations because of the presence of different cohorts and family clustering (Wahlund effect) is possible as sponges are long lived and particularly I. fasciculata possesses highly philopatric larvae (Mariani et al., 2006). In summary, both inbreeding and the existence of substructure might be the factors that most likely are causing the deviation of HWE in our I. fasciculata populations.

Population structure and connectivity in I. fasciculata

The populations of I. fasciculata showed genetic structure at both large and small geographical scales. First, two major clusters were detected across the sampling site covered in this study, one grouping the Alboran Sea locations and the Thyrrenian and Adriatic Sea locations, and the other one clustering the locations along the Western Mediterranean coast of Spain and the Balearic and Corsica Islands (Figure 2a). However, the Mantel test performed along the entire sampling range of our study did not reveal a pattern of stepping stone gene flow (derived from a process of IBD), suggesting that other major processes such as the existence of oceanographic barriers (for example, major currents) may be driving population differentiation patterns in this area. In fact, three barriers to gene flow were detected in our data set: the strongest barrier appeared to separate the Alboran Sea locations from those in the rest of the Mediterranean Sea (presumably the Almeria-Oran Front, Figure 4), and this was also correlated with the limited gene flow detected between these areas and the high population differentiation observed between both regions. For many marine organisms, the Almeria-Oran Front acts as a strong barrier for gene flow between Atlantic and Mediterranean populations (see review in Patarnello et al., 2007), including sponges (see, for example, Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015). In contrast, stepping stone gene flow was observed when analyzing the spatial distribution of genetic divergence exclusively between the Western and Thyrrenian and Adriatic locations. The other two barriers detected corresponded to the North-Balearic Front and the Ligurian-Thyrrenian barrier (Figure 4). As found for other benthic organisms (Villamor et al., 2014), the Ligurian-Thyrrenian barrier appeared to be a seasonal barrier, and it did not completely prevent the gene flow between populations across it.

Population differentiation was also detected at smaller scales: significant differences were detected between all pairwise comparisons except for the closely located sites of CAI and ESC in the North-Western coast of Spain, and the distantly located pairs of ESC and ALI, TAR and CAB and ESC and CRO (Figure 2c). Although high gene flow may be expected between CAI and ESC (only located 50 km apart), the extensive gene flow detected among the other 3 site pairs (located between 550 and 2250 km apart) does not have a straightforward explanation. In general, populations of sessile invertebrates with relatively low dispersal capabilities in the Mediterranean are highly structured like those of I. fasciculata, including not only sponges (Duran et al., 2004; Blanquer and Uriz, 2010; Dailianis et al., 2011; Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015), but also cnidarians and ascidians (Goffredo et al., 2004; López-Legentil and Turon, 2006; Pérez-Portela and Turon, 2008; Mokhtar-Jamaï et al., 2011). Even sponges from other distant regions show high values of population differentiation (Chaves‐Fonnegra et al., 2015; Giles et al., 2015). The overall FST value of genetic differentiation found for I. fasciculata (FST=0.221) was higher than that reported for the closely related dictyoceratid S. officinalis (FST=0.061, Dailianis et al., 2011), but similar to other Mediterranean demosponges studied using microsatellites (C. crambe: FST=0.18, Duran et al., 2004; S. lophyropoda: FST=0.122, Blanquer and Uriz, 2010; S. lamella: FST=0.236, Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015) and even corals, such as Balanophyllia europaea (0.202; Goffredo et al., 2004), indicating that the differentiation patterns in these Mediterranean benthic invertebrates might be equally driven by the inbreeding caused by the low dispersal abilities of their larvae, and the occurrence of oceanographic barriers to their gene flow.

Demographic effects of mass mortalities in I. fasciculata

Recent reductions in the effective population size (or bottlenecks) have been detected in almost all the studied sites of I. fasciculata except for CAI, ALI and CAL depending on the model used. During a bottleneck and under the infinite allele model, allelic diversity is reduced faster than the heterozygosity. However, under the strict stepwise mutation model and probably under the two-phase model, heterozygosity excess may not be observed (Cornuet and Luikart, 1996). In our case, the different results in the detection of bottlenecks under different models may be reflecting differences in the resolution of the analyses rather than inconclusive results. In fact, these reductions in population size can well be related to recent episodes of massive individual losses reported for I. fasciculata (see, for example, Garrabou et al., 2009; Maldonado et al., 2010b; Cebrian et al., 2011). Even though a massive episode of mortality was observed in ALI in 2008 (Maldonado et al., 2010b), a bottleneck was not detected with our genetic analysis. The most parsimonious explanations for our observation are that (1) ALI was unaffected by genetic drift after massive dye-offs and/or (2) that this location is well connected (by means of gene flow) with other nearby I. fasciculata populations. Indeed, the largest number of migrants from last generation was detected in ALI, suggesting higher migration rates toward this location.

Phylogenetic analyses and hybridization between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata

Previous analysis using COI sequences did not provide enough resolution to delimit I. variabilis and I. fasciculata species, but analyses of the nuclear ribosomal gene ITS-2 showed that they formed different clades with a divergence of 2.97%±0.38 (Erwin et al., 2012b). Similarly, our results show that COI did not separate I. variabilis and I. fasciculata because they form together a well-supported but unresolved clade, with shared haplotypes between both species. This was not surprising, as nucleotide substitution rates in the mitochondrial genome in sponges and other lower metazoans are up to 100 times slower than other animal lineages (Hellberg, 2006; Shearer et al., 2002). In this sense, although COI has been previously found to be useful to explain speciation and phylogeographic patterns in some haplosclerid sponges (see, for example, López-Legentil and Pawlik, 2009; DeBiasse and Hellberg, 2015), it seems to be unsuitable for resolving phylogenetic relationships in other sponges (see, for example, Duran et al., 2004; Dailianis et al., 2011). In light of these results, two possible explanations arise: the first one is that they are separate but closely related species that have undergone secondary contact favoring introgression, and a second explanation may be that I. variabilis and I. fasciculata are the same species but are currently undergoing incipient speciation without reproductive isolation yet occurring, and therefore a certain level of mixing still exists. Both the reciprocal monophyly of ITS-2 sequence clades and the existence of some morphological differences between these two species lend support to our first hypothesis. In addition, it is important to note here that our molecular results do not support the reassignment of I. fasciculata to the genus Sarcotragus, as previously proposed by Pronzato et al. (2004), as I. fasciculata and the type species for Sarcotragus (S. spinulosus) appear in two separated and clearly divergent clades (Figure 6a).

Instead of using COI, several authors have suggested multilocus (for example, nuclear coding genes, amplified fragment length polymorphisms, microsatellites and single-nucleotide polymorphisms) approaches as potentially suitable for resolving species boundaries (Petit and Excoffier, 2009; Hausdorf and Hennig, 2010). In particular, microsatellite loci are characterized by relatively high mutation rates, an assumed neutral selection rate and expected lower introgression potential than mitochondrial markers for at least some organisms (Petit and Excoffier, 2009). Our results using microsatellite loci suggested that some degree of hybridization and introgression occur in at least some populations where both species of Ircinia appear in sympatry (Figures 6b and c). Introgression between closely related species with overlapping ranges and incomplete reproductive barriers (such as the Ircinia species here) is common in marine invertebrates (see, for example, Willis et al., 2006) even when the divergence between species is relatively large (Nydam and Harrison, 2011). Interestingly, introgression could be increased when intraspecific gene flow decreases (Petit and Excoffier, 2009). Thus, as the number and densities of Ircinia populations decrease in the Mediterranean Sea, a concomitant decrease in gene flow among affected populations may be accompanied by higher hybridization rates between I. variabilis and I. fasciculata populations, further blurring these two species boundaries. Although the relationship between intra- and interspecific gene flow is mostly documented for human populations (Currat et al., 2008), the hybridization patterns of I. fasciculata reported here might be a first step toward understanding the impact of introgression in the genetic diversity and structure of marine invertebrates after population reductions.

In conclusion, our results agree with previous studies on the genetic differentiation of sessile invertebrates with lecithotrophic larvae and limited dispersal potential in the Mediterranean Sea (Duran et al., 2004; Goffredo et al., 2004; Pérez-Portela and Turon, 2008; Blanquer and Uriz, 2010; Dailianis et al., 2011; Mokhtar-Jamaï et al., 2011; Pérez‐Portela et al., 2015), highlighting the important role of oceanographic barriers in shaping the genetic structure across their distribution (Patarnello et al., 2007; Villamor et al., 2014). In particular, we found that most locations of I. fasciculata are strongly genetically differentiated, with barriers preventing gene flow between many population pairs that correlate with well-known oceanographic barriers. Importantly, our results indicate that the genetic diversity of I. fasciculata is threatened by massive demographic losses in the Mediterranean Sea, and that its recovery is hindered by limited connectivity between populations. Demographic reductions of I. fasciculata in the Alboran sites might be especially worrisome, as these locations are genetically isolated from the rest. Interestingly, the hybridization potential observed between I. fasciculata and I. variabilis may allow the former to maintain a genetic pool large enough to palliate genetic diversity losses. Notably, increased introgression events among these species may offset reductions in intraspecific gene flow resulting from stress and mass mortality events.

Data archiving

All data sets have been archived in PANGAEA https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.860018.

References

Addison JA, Hart MW . (2005). Spawning, copulation and inbreeding coefficients in marine invertebrates. Biol Lett 1: 450–453.

Bierne N, Borsa P, Daguin C, Jollivet D, Viard F, Bonhomme F et al. (2003). Introgression patterns in the mosaic hybrid zone between Mytilus edulis and M. galloprovincialis. Mol Ecol 12: 447–461.

Blanquer A, Uriz MJ . (2010). Population genetics at three spatial scales of a rare sponge living in fragmented habitats. BMC Evol Biol 10: 13.

Calderon I, Ortega N, Duran S, Becerro M, Pascual M, Turon X . (2007). Finding the relevant scale: clonality and genetic structure in a marine invertebrate (Crambe crambe, Porifera). Mol Ecol 16: 1799–1810.

Cebrian E, Agell G, Martí R, Uriz MJ . (2006). Response of the Mediterranean sponge Chondrosia reniformis Nardo to copper pollution. Environ Pollut 141: 452–458.

Cebrian E, Uriz MJ, Garrabou J, Ballesteros E . (2011). Sponge mass mortalities in a warming Mediterranean Sea: are cyanobacteria-harboring species worse off? PLoS One 6: e20211.

Chapuis MP, Estoup A . (2007). Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol Biol Evol 24: 621–631.

Chaves‐Fonnegra A, Feldheim KA, Secord J, Lopez JV . (2015). Population structure and dispersal of the coral‐excavating sponge Cliona delitrix. Mol Ecol 24: 1447–1466.

Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA . (2000). TCS: a computer program to estimate gene geneologies. Mol Ecol 9: 1657–1660.

Commendatore MG, Esteves JL, Colombo JC . (2000). Hydrocarbons in coastal sediments of Patagonia, Argentina: levels and probable sources. Mar Pollution Bull 40: 989–998.

Cornuet JM, Luikart G . (1996). Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 144: 2001–2014.

Currat M, Ruedi M, Petit RJ, Excoffier L . (2008). The hidden side of invasions: massive introgression by local genes. Evolution 62: 1908–1920.

Dailianis T, Tsigenopoulos CS, Dounas C, Voultsiadou E . (2011). Genetic diversity of the imperilled bath sponge Spongia officinalis Linnaeus, 1759 across the Mediterranean Sea: patterns of population differentiation and implications for taxonomy and conservation. Mol Ecol 20: 3757–3772.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D . (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9: 772–772.

DeBiasse MB, Hellberg ME . (2015). Discordance between morphological and molecular species boundaries among Caribbean species of the reef sponge Callyspongia. Ecol Evol 5: 663–675.

de Goeij JM, van Oevelen D, Vermeij MJ, Osinga R, Middelburg JJ, de Goeij AF et al. (2013). Surviving in a marine desert: the sponge loop retains resources within coral reefs. Science 342: 108–110.

Diaz MC., Rützler K . (2001). Sponges: an essential component of Caribbean coral reefs. Bull Mar Sci 69: 535–546.

Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB . (1977). Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B (Method) 39: 1–38.

Duran S, Pascual M, Estoup A, Turon X . (2004). Strong population structure in the marine sponge Crambe crambe (Poecilosclerida) as revealed by microsatellite markers. Mol Ecol 13: 511–522.

Erwin PM, López-Legentil S, Turon X . (2012a). Ultrastructure, molecular phylogenetics and chlorophyll a content of novel cyanobacterial symbionts in temperate sponge hosts. Microb Ecol 64: 771–783.

Erwin PM, López-Legentil S, Gonzalez-Pech R, Turon X . (2012b). A specific mix of generalists: bacterial symbionts in Mediterranean Ircinia spp. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 79: 619–637.

Escobar D, Zea S, Sánchez JA . (2012). Phylogenetic relationships among the Caribbean members of the Cliona viridis complex (Porifera, Demospongiae, Hadromerida) using nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogent Evol 64: 271–284.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J . (2005). Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14: 2611–2620.

Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S . (2005). Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online 1: 47.

Frankham R . (2005). Genetics and extinction. Biol Conserv 126: 131–140.

Frankham R . (2010). Challenges and opportunities of genetic approaches to biological conservation. Biol Conserv 143: 1919–1927.

Freeland J, Kirk H, Petersen SD . (2011) Molecular Ecology. Wiley-Blackwell: UK. pp 1–449.

Gaggiotti OE, Lange O, Rassmann K, Gliddon C . (1999). A comparison of two indirect methods for estimating average levels of gene flow using microsatellite data. Mol Ecol 8: 1513–1520.

Garrabou J, Coma R, Bensoussan N, Bally M, Chevaldonné P, Cigliano M et al. (2009). Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Global Change Biol 15: 1090–1103.

Giles EC, Saenz‐Agudelo P, Hussey NE, Ravasi T, Berumen ML . (2015). Exploring seascape genetics and kinship in the reef sponge Stylissa carteri in the Red Sea. Ecol Evol 5: 2487–2502.

Goffredo S, Mezzomonaco L, Zaccanti F . (2004). Genetic differentiation among populations of the Mediterranean hermaphroditic brooding coral Balanophyllia europaea (Scleractinia: Dendrophylliidae). Mar Biol 145: 1075–1083.

Goudet J . (1995). FSTAT (version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered 86: 485–486.

Guindon S, Gascuel O . (2003). A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52: 696–704.

Harper FM, Hart MW . (2007). Morphological and phylogenetic evidence for hybridization and introgression in a sea star secondary contact zone. Invertebr Biol 126: 373–384.

Hausdorf B, Hennig C . (2010). Species delimitation using dominant and codominant multilocus markers. Syst Biol 59: 491–503.

Hauser L, Carvalho GR . (2008). Paradigm shifts in marine fisheries genetics: ugly hypotheses slain by beautiful facts. Fish Fish 9: 333–336.

Hellberg ME . (2006). No variation and low synonymous substitution rates in coral mtDNA despite high nuclear variation. BMC Evol Biol 6: 24.

Hughes TP, Baird AH, Bellwood DR, Card M, Connolly SR, Folke C et al. (2003). Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301: 929–933.

Ilan M, Ben-Eliahu MN, Galil B . (1994). Three deep water sponges from the eastern Mediterranean and their associated fauna. Ophelia 39: 45–54.

Jombart T . (2008). Adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24: 1403–1405.

Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma KI, Miyata T . (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3059–3066.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649.

Kopelman NM, Mayzel J, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA, Mayrose I . (2015). CLUMPAK: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol Ecol Res 15: 1179–1191.

Laboy-Nieves EN, Klein E, Conde JE, Losada F, Cruz JJ, Bone D . (2001). Mass mortality of tropical marine communities in Morrocoy, Venezuela. Bull Mar Sci 68: 163–179.

Ledoux JB, Garrabou J, Bianchimani O, Drap P, Féral JP, Aurelle D . (2010). Fine-scale genetic structure and inferences on population biology in the threatened Mediterranean red coral, Corallium rubrum. Mol Ecol 19: 4204–4216.

López-Legentil S, Pawlik JR . (2009). Genetic structure of the Caribbean giant barrel sponge Xestospongia muta using the I3-M11 partition of COI. Coral Reefs 28: 157–165.

López-Legentil S, Turon X . (2006). Population genetics, phylogeography and speciation of Cystodytes (Ascidiacea) in the western Mediterranean Sea. Biol J Linn Soc 88: 203–214.

Luikart G, Cornuet JM . (1998). Empirical evaluation of a test for identifying recently bottlenecked populations from allele frequency data. Conserv Biol 12: 228–237.

Maldonado M, Riesgo A . (2008). Reproduction in Porifera: a synoptic overview. Treballs Soc Catalana Biol 59: 29–49.

Maldonado M, Riesgo A, Bucci A . (2010a). Revisiting silicon budgets at a tropical continental shelf: Silica standing stocks in sponges surpass those in diatoms. Limnol Oceanogr 55: 2001–2010.

Maldonado M, Sánchez-Tocino L, Navarro C . (2010b). Recurrent disease outbreaks in corneous demosponges of the genus Ircinia: epidemic incidence and defense mechanisms. Mar Biol 157: 1577–1590.

Manni F, Guerard E, Heyer E . (2004). Geographic patterns of (genetic, morphologic, linguistic) variation: how barriers can be detected by using Monmonier's algorithm. Hum Biol 76: 173–190.

Mariani S, Uriz MJ, Turon X, Alcoverro T . (2006). Dispersal strategies in sponge larvae: integrating the life history of larvae and the hydrologic component. Oecologia 149: 174–184.

McClintock JB, Amsler CD, Baker BJ, Van Soest RWM . (2005). Ecology of Antarctic marine sponges: an overview. Integr Comp Biol 45: 359–368.

Meirmans PG, Van Tienderen PH . (2004). GENOTYPE and GENODIVE: two programs for the analysis of genetic diversity of asexual organisms. Mol Ecol Notes 4: 792–794.

Meyer CP, Geller JB, Paulay G . (2005). Fine scale endemism on coral reefs: archipelagic differentiation in turbinid gastropods. Evolution 59: 113–125.

Mokhtar-Jamaï K, Pascual M, Ledoux JB, Coma R, Féral JP, Garrabou J et al. (2011). From global to local genetic structuring in the red gorgonian Paramuricea clavata: the interplay between oceanographic conditions and limited larval dispersal. Mol Ecol 20: 3291–3305.

Mokhtar-Jamaï K, Coma R, Wang J, Zuberer F, Féral JP, Aurelle D . (2013). Role of evolutionary and ecological factors in the reproductive success and the spatial genetic structure of the temperate gorgonian Paramuricea clavata. Ecol Evol 3: 1765–1779.

Narum SR . (2006). Beyond Bonferroni: less conservative analyses for conservation genetics. Conserv Genet 7: 783–787.

Nydam ML, Harrison RG . (2011). Introgression despite substantial divergence in a broadcast spawning marine invertebrate. Evolution 65: 429–442.

Patarnello T, Volckaert FA, Castilho R . (2007). Pillars of Hercules: is the Atlantic–Mediterranean transition a phylogeographical break? Mol Ecol 16: 4426–4444.

Peakall ROD, Smouse PE . (2006). GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes 6: 288–295.

Pérez T, Garrabou J, Sartoretto S, Harmelin JG, Francour P, Vacelet J . (2000). Massive mortality of marine invertebrates: an unprecedented event in northwestern Mediterranean. C R Acad Sci III 323: 853–865.

Pérez T, Vacelet J . (2014). Effect of climatic and anthropogenic disturbances on sponge fisheries. In: Stefano Goffredo, Zvy Dubinsky (eds) The Mediterranean Sea. Springer: The Netherlands. pp 577–587.

Pérez-Portela R, Cerro-Gálvez E, Taboada S, Tidu C, Campillo-Campbell C, Mora J et al. (2016). Lonely giants in the deep: genetic structure of the red gorgonian at the head of the submarine canyons of the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Coral Reefs doi:10.1007/s00338-016-1431-2.

Pérez‐Portela R, Noyer C, Becerro MA . (2015). Genetic structure and diversity of the endangered bath sponge Spongia lamella. Aquatic Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosys 25: 365–379.

Pérez-Portela R, Turon X . (2008). Cryptic divergence and strong population structure in the colonial invertebrate Pycnoclavella communis (Ascidiacea) inferred from molecular data. Zoology 111: 163–178.

Petit RJ, Excoffier L . (2009). Gene flow and species delimitation. Trends Ecol Evol 24: 386–393.

Pita L, Turon X, López‐Legentil S, Erwin PM . (2013). Host rules: spatial stability of bacterial communities associated with marine sponges (Ircinia spp.) in the Western Mediterranean Sea. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 86: 268–276.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P . (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959.

Pronzato R, Malva R, Manconi R . (2004). The taxonomic status of Ircinia fasciculata, Ircinia felix, and Ircinia variabilis (Dictyoceratida, Irciniidae). Sponge Science in the New Millennium. Boll Mus Ist Biol Univ Genova Vol 68 pp 553–563.

Puechmaille S . (2016). The program STRUCTURE does not reliably recover the correct population structure when sampling is uneven: sub-sampling and new estimators alleviate the problem. Mol Ecol Resour 16: 608–627.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ . (2007). Tracer v1. 4: MCMC trace analyses tool. See http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/.

Raymond M, Rousset F . (1995). GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered 86: 248–249.

Riesgo A, Blasco G, Erwin PM, Pérez-Portela R, López-Legentil S . (2014). Optimization of 14 microsatellite loci in a Mediterranean demosponge subjected to population decimation, Ircinia fasciculata. Conserv Genet Res 6: 301–303.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP . (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574.

Rot C, Goldfarb I, Ilan M, Huchon D . (2006). Putative cross-kingdom horizontal gene transfer in sponge (Porifera) mitochondria. BMC Evol Biol 6: 71.

Sala E, Knowlton N . (2006). Global marine biodiversity trends. Annu Rev Environ Resour 31: 93–122.

Schunter C, Carreras-Carbonell J, Macpherson E, Tintoré J, Vidal-Vijande E, Pascual A et al. (2011). Matching genetics with oceanography: directional gene flow in a Mediterranean fish species. Mol Ecol 20: 5167–5181.

Shearer TL, Van Oppen MJH, Romano SL, Wörheide G . (2002). Slow mitochondrial DNA sequence evolution in the Anthozoa (Cnidaria). Mol Ecol 11: 2475–2487.

Spalding MD, Fox HE, Allen GR, Davidson N, Ferdaña ZA, Finlayson MAX et al. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 57: 573–583.

Spielman D, Brook BW, Frankham R . (2004). Most species are not driven to extinction before genetic factors impact them. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15261–15264.

Stabili L, Cardone F, Alifano P, Tredici SM, Piraino S, Corriero G et al. (2012). Epidemic mortality of the sponge Ircinia variabilis (Schmidt, 1862) associated to proliferation of a Vibrio bacterium. Microb Ecol 64: 802–813.

Turon X, Garriga A, Erwin PM . (2013). Lights and shadows: growth patterns in three sympatric and congeneric sponges (Ircinia spp.) with contrasting abundances of photosymbionts. Mar Biol 160: 2743–2754.

Villamor A, Costantini F, Abbiati M . (2014). Genetic structuring across marine biogeographic boundaries in rocky shore invertebrates. PLoS One 9: e101135.

Waples RS . (2015). Testing for Hardy–Weinberg proportions: have we lost the plot? J Hered 106: 1–19.

Webster NS . (2007). Sponge disease: a global threat? Environ Microbiol 9: 1363–1375.

Webster NS, Pantile R, Botte E, Abdo D, Andreakis N, Whalan S . (2013). A complex life cycle in a warming planet: gene expression in thermally stressed sponges. Mol Ecol 22: 1854–1868.

Willis BL, van Oppen MJ, Miller DJ, Vollmer SV, Ayre DJ . (2006). The role of hybridization in the evolution of reef corals. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 1: 489–517.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs Turon and Cebrian (CEAB-CSIC), Juan Moles (University of Barcelona) and Alejandro Terrón-Sigler (Fundación Hombre y Territorio) for supplying some of the samples. This research was funded by the Spanish Government project MARSYMBIOMICS CTM2013-43287-P and the Catalan Government Grant 2014SGR-336 for Consolidated Research Groups.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Riesgo, A., Pérez-Portela, R., Pita, L. et al. Population structure and connectivity in the Mediterranean sponge Ircinia fasciculata are affected by mass mortalities and hybridization. Heredity 117, 427–439 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.41

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.41

This article is cited by

-

Novel microsatellite markers suggest significant genetic isolation in the Eastern Pacific sponge Aplysina gerardogreeni

Molecular Biology Reports (2024)

-

Exceptional population genomic homogeneity in the black brittle star Ophiocomina nigra (Ophiuroidea, Echinodermata) along the Atlantic-Mediterranean coast

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A multi-bioassay integrated approach to assess antifouling potential of extracts from the Mediterranean sponge Ircinia oros

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Oceanographic features and limited dispersal shape the population genetic structure of the vase sponge Ircinia campana in the Greater Caribbean

Heredity (2021)

-

Genetic homogeneity, lack of larvae recruitment, and clonality in absence of females across western Mediterranean populations of the starfish Coscinasterias tenuispina

Scientific Reports (2021)