Abstract

The linkage disequilibrium method is currently the most widely used single sample estimator of genetic effective population size. The commonly used software packages come with two options, referred to as the parametric and jackknife methods, for computing the associated confidence intervals. However, little is known on the coverage performance of these methods, and the published data suggest there may be some room for improvement. Here, we propose two new methods for generating confidence intervals and compare them with the two in current use through a simulation study. The new confidence interval methods tend to be conservative but outperform the existing methods for generating confidence intervals under certain circumstances, such as those that may be encountered when making estimates using large numbers of single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective population size (Ne) is an important parameter of interest to the study of evolutionary biology as well as for monitoring species of conservation concern. The linkage disequilibrium method is the most commonly used genetic estimator of contemporary Ne. Its popularity stems from its ability to make powerful estimates from single samples, whereas the so-called temporal methods require two or more samples from a population separated in time. The linkage disequilibrium method is also easily accessible through several software packages, namely the programs LDNe (Waples and Do, 2008) and NeEstimator 2.0 (Do et al., 2014).

There are a number of studies investigating the effectiveness of the linkage disequilibrium method (Waples, 2005; Waples and Gaggiotti, 2006; Luikart et al., 2010; Waples and Do, 2010). However, there is little work published with regard to the performance of the associated confidence intervals. From the statistical perspective,  , like any other estimator, is a random variable with a distribution. Unfortunately, the distribution of

, like any other estimator, is a random variable with a distribution. Unfortunately, the distribution of  is not easy to characterize, and therefore the exact confidence intervals are not available. The current practice is based on a scaled χ2 distribution. However, the corresponding number of degrees of freedom is not well defined because of the intrinsic correlations between individual estimates of linkage disequilibrium that are combined to estimate Ne.

is not easy to characterize, and therefore the exact confidence intervals are not available. The current practice is based on a scaled χ2 distribution. However, the corresponding number of degrees of freedom is not well defined because of the intrinsic correlations between individual estimates of linkage disequilibrium that are combined to estimate Ne.

For any method of generating confidence intervals at any significance level, the true value of an estimated parameter must inevitably fall in some proportion of confidence intervals. Ideally, for accurate confidence intervals generated at a significance level of α, this proportion will be (1−α) in the long run. That is to say, if a researcher were to generate many 95% confidence intervals, they ought to be able to expect that 95% of the time the true value of the parameter they are estimating will lie in its interval. If the intervals are set too narrowly then the true values will not lie in the confidence intervals as often as they should and the certainty of the estimates will be overstated. This is referred to as being anticonservative. The proportion of the time that confidence intervals do actually contain the true value of the estimated parameter is commonly referred to as the coverage probability. Conversely, if the coverage probability is too high the confidence interval is said to be conservative.

If confidence intervals are to be valid and useful, the coverage probability ought to be the same as the nominal value for that interval (that is, 0.95 for a 95% confidence interval). This ought to hold for all values of α, not just the standard 0.05/95% case. It should also hold for all values of any other parameters that may affect the estimates. In the case of effective population size, these include population size (N), number of loci (L), number of alleles at each locus (K) and sample size (S).

A direct method to determine confidence intervals for linkage disequilibrium estimates of population size was not provided in the original formulation of the method (Hill, 1981). The LDNE (Waples and Do, 2008) and NeEstimator 2.0 (Do et al., 2014) software packages provide two methods for generating confidence intervals. The first, referred to as the ‘parametric method’ (Waples, 2006), is based on a technique used for confidence intervals for the temporal method (Waples, 1989). It takes the distribution for  to be a χ2 distribution with the degrees of freedom being equal to the total number of ‘independent comparisons’ used in the estimation.

to be a χ2 distribution with the degrees of freedom being equal to the total number of ‘independent comparisons’ used in the estimation.

The second is a ‘jackknife’-based correction to this method (Waples and Do, 2008). An approximate relationship using a reestimated parameter is used to adjust the degrees of freedom in the χ2 distribution in the confidence interval. The rationale behind this technique is that the true value for the degrees of freedom in the χ2 distribution used in confidence intervals is less than the total number of comparisons, because the comparisons are not all independent. As such, we expect that the performance of the ‘parametric method’ and perhaps also this ‘jackknife’-based correction will decline as the total number of comparisons grows.

However, strictly speaking, this method is not actually a jackknife technique as no observations (individuals) are being removed and only predictors (loci pairs). This is illustrated by the fact that no new calculations are needed for finding the new values, and only a reaveraging of existing values. However, if individuals were removed one at a time instead, the linkage would have to be recalculated for each loci pair every time. In addition, the variance is not estimated in the standard jackknife manner. Henceforth, we refer to this method as ‘pseudo-jackknife’. Although the pseudo-jackknife requires more computation time than the parametric method, a full jackknife based on individuals would require yet more.

Published confidence interval results for the parametric and pseudo-jackknife methods (Waples and Do, 2008) show it is possible for the confidence intervals to be insufficiently conservative and contain fewer than the nominal proportion of values. For instance, a nominal 95% interval may on average only contain the true value 80% of the time. These results suggest that there is room for improvement in the performance of these confidence intervals.

Two variations of the application of the jackknife are proposed and tested in this paper as possible improvements on the existing techniques. To test a confidence interval method it is necessary to know the true value of the parameter being estimated. This means that for genetic estimates of Ne, simulated populations are required. The simplest method to empirically test the coverage probability for a given method of generating confidence intervals is to simulate a large number of replicate populations with known Ne, make estimates of this Ne and produce the associated confidence intervals, and then see how often the (known) true value falls inside these intervals. The proportion of intervals containing the true value will estimate the coverage probability for that method.

There is reason to believe that current methods for generating confidence intervals for estimates of Ne using the linkage disequilibrium method may be suboptimal in at least some cases. Two newer methods are proposed that may outperform the older methods and all were tested on wide range of simulated population scenarios. The performance of all four methods in terms of coverage probability is examined, with the objective of recommending under which circumstances, if any, each of the methods should be used.

Materials and methods

Effective population size estimation

The original, uncorrected, formula for  (Hill, 1981) is given by

(Hill, 1981) is given by

where S is the samples size and  is a measure of the association between alleles at different loci. However, this formula was corrected based on empirical work (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2008), and replaced in practice by

is a measure of the association between alleles at different loci. However, this formula was corrected based on empirical work (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2008), and replaced in practice by

for the case of random mating with a sample size >30. Similar formulae for other cases were also given.

The linkage disequilibrium method was originally derived for the case of one pair of loci with two alleles per locus (Hill, 1981). Where there are more than two alleles at a locus, the alleles must be split up and the pairwise estimates from each allele pairs (one from each locus) must be averaged within that loci pair before the average across loci pairs is taken. Each value of  is estimated in practice using the Burrows’ Composite Method (Cockerham and Weir, 1977) that is robust to deviations from pure random mating and unbiased when corrected by a factor of S/(S−1) (Weir, 1979). The full formula is

is estimated in practice using the Burrows’ Composite Method (Cockerham and Weir, 1977) that is robust to deviations from pure random mating and unbiased when corrected by a factor of S/(S−1) (Weir, 1979). The full formula is

where Δ is the original Burrows coefficient, S is the sample size, p(q) is the observed frequency of the allele at the first (second) locus and pA and pB are the frequencies of homozygotes of the alleles at their respective loci.

In all cases we examined,  is averaged across loci pairs according to the methodology used in the NeEstimator 2.0 (Do et al., 2014) software as based on earlier work (Waples and Do, 2008). This global average is referred to as

is averaged across loci pairs according to the methodology used in the NeEstimator 2.0 (Do et al., 2014) software as based on earlier work (Waples and Do, 2008). This global average is referred to as  . We do not examine the case of missing data and thus did not have recourse to the weighting techniques that have been developed for this (Peel et al., 2013).

. We do not examine the case of missing data and thus did not have recourse to the weighting techniques that have been developed for this (Peel et al., 2013).

This averaging of many estimates gives rise to the idea of a total number of comparisons, J, used in making an estimate. A single ‘comparison’ is the estimate of  produced by a single pair of alleles, one each from a pair of loci. If there are L loci and each locus i has Ki alleles then the total number of nominally independent comparisons according to this method is

produced by a single pair of alleles, one each from a pair of loci. If there are L loci and each locus i has Ki alleles then the total number of nominally independent comparisons according to this method is

For example, with 10 loci and 15 alleles per loci, J=8820. This is a fairly typical result in practice.

A complication in the calculation of  is that rare alleles are known to cause bias. That is, alleles with low observed frequencies tend to produce upwardly biased estimates (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2010). The standard method to deal with this problem is to discard all values of

is that rare alleles are known to cause bias. That is, alleles with low observed frequencies tend to produce upwardly biased estimates (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2010). The standard method to deal with this problem is to discard all values of  produced from allele pairs where one or both members of the pair have an observed frequency (proportion) below a given cutoff. This cutoff is referred to as Pcrit and is typically in the range [0, 0.1]. This affects the confidence intervals for

produced from allele pairs where one or both members of the pair have an observed frequency (proportion) below a given cutoff. This cutoff is referred to as Pcrit and is typically in the range [0, 0.1]. This affects the confidence intervals for  in several ways. Although removing low frequency alleles reduces bias, it also increases the variance of the estimate (Waples and Do, 2010). Removing alleles also decreases the number of comparisons used in the calculation. The results from two values of Pcrit are reported for this study, 0, that is with no alleles removed at all, and 0.05, a moderately high value.

in several ways. Although removing low frequency alleles reduces bias, it also increases the variance of the estimate (Waples and Do, 2010). Removing alleles also decreases the number of comparisons used in the calculation. The results from two values of Pcrit are reported for this study, 0, that is with no alleles removed at all, and 0.05, a moderately high value.

Simulated populations

The software package SimuPOP (Peng and Kimmel, 2005) was used to simulate standardized populations with known effective population sizes for the testing of the various confidence interval methods. The populations were individual based, forward time simulations with discrete generations and unlinked loci.

It is known that in such simulations, the realized Ne will not match the nominal value but will vary somewhat between simulated generations (Waples and Faulkner, 2009). As such, for the purposes of determining whether a confidence interval contained the true value or not, the demographic effective population size was calculated for each case. The appropriate formula (Crow and Denniston, 1988) is

for the case of separate sexes. N is the population size,  is the mean number of offspring per individual and Vk is the variance of the same quantity. Fortunately, all of these parameters are easily retrieved from the simulation data. The linkage disequilibrium method estimates the population of the parental generation of the sampled generation. However, the linkage ‘signal’ from prior generations also persists, declining by a factor of 2 every generation. The true value for Ne, to be compared with its estimates, is taken to be the harmonic mean of the demographic Ne for the 4 generations before the sampled generation, weighted by their relative contributions that halve each generation further back in time (that is, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625).

is the mean number of offspring per individual and Vk is the variance of the same quantity. Fortunately, all of these parameters are easily retrieved from the simulation data. The linkage disequilibrium method estimates the population of the parental generation of the sampled generation. However, the linkage ‘signal’ from prior generations also persists, declining by a factor of 2 every generation. The true value for Ne, to be compared with its estimates, is taken to be the harmonic mean of the demographic Ne for the 4 generations before the sampled generation, weighted by their relative contributions that halve each generation further back in time (that is, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625).

The simulations encompassed a wide variety of scenarios with varying sample sizes (S), population sizes (N), number of alleles per locus (K), number of loci (L), allele frequency distributions and number of burn-in generations (g). Table 1 summarizes these scenarios and also includes the associated value of the total number of comparisons, J, believed to be the main factor in the decline in confidence interval performance. It reports them in terms of Jmax, the total number of comparisons if no alleles go to extinction during the simulation and no rare alleles are discarded, as well as a figure for how many comparisons are actually used when a Pcrit of 0.05 is applied. This second figure is an average across all of the replicate populations for that scenario.

Current methods

With all of the methods we initially find a confidence interval for  . The upper and lower bounds are then placed in either Equation (2) to produce the equivalent bounds for Ne. The parametric method assumes the value

. The upper and lower bounds are then placed in either Equation (2) to produce the equivalent bounds for Ne. The parametric method assumes the value  has a χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom, where J is the total number of ‘independent comparisons’ used to calculate

has a χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom, where J is the total number of ‘independent comparisons’ used to calculate  , as in Equation (4). In the simplest case of a two loci with two alleles each,

, as in Equation (4). In the simplest case of a two loci with two alleles each,  has an approximately χ2 distribution (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2008) with a single degree of freedom. The sum of these estimates

has an approximately χ2 distribution (Waples, 2006; Waples and Do, 2008) with a single degree of freedom. The sum of these estimates  can be scaled to a χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom if all of the

can be scaled to a χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom if all of the  are independent. Thus, a (1−α) confidence interval for

are independent. Thus, a (1−α) confidence interval for  is

is

The notation  indicates the (α/2)th percentile of χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom. As has been noted (Waples, 2006), this will overestimate the true degrees of freedom as it does not account for potential correlations between the comparisons. It is expected that this approximation will worsen as J increases (Do et al., 2014).

indicates the (α/2)th percentile of χ2 distribution with J degrees of freedom. As has been noted (Waples, 2006), this will overestimate the true degrees of freedom as it does not account for potential correlations between the comparisons. It is expected that this approximation will worsen as J increases (Do et al., 2014).

The pseudo-jackknife builds on the parametric method but tries to account for the fact that the pairs of alleles used to estimate  are not actually independent of each other. Multiple estimates within a pair of loci will obviously have correlations and even if all loci are independently segregating, loci pairs that share a member will be correlated. It is possible (Hill, 1981) to make an approximation to the degree of freedom by J≈2/φ where φ=Var(r2)/(r2)2 is the coefficient of variation. This approximation comes from derivation of the simple two locus case with no covariance structure. This relationship is used (Waples, 2006) to reapproximate J using a pseudo-jackknifed estimate of φ (Waples and Do, 2008). With L loci the total number of loci pairs is L(L−1)/2. Each pair is removed one at a time and

are not actually independent of each other. Multiple estimates within a pair of loci will obviously have correlations and even if all loci are independently segregating, loci pairs that share a member will be correlated. It is possible (Hill, 1981) to make an approximation to the degree of freedom by J≈2/φ where φ=Var(r2)/(r2)2 is the coefficient of variation. This approximation comes from derivation of the simple two locus case with no covariance structure. This relationship is used (Waples, 2006) to reapproximate J using a pseudo-jackknifed estimate of φ (Waples and Do, 2008). With L loci the total number of loci pairs is L(L−1)/2. Each pair is removed one at a time and  is computed in each case, φi being the coefficient of variation calculated using

is computed in each case, φi being the coefficient of variation calculated using  , the estimate of

, the estimate of  all but the ith pair of loci. The sample variance is used to estimate

all but the ith pair of loci. The sample variance is used to estimate  , rather than the jackknife variance formula. These are then averaged

, rather than the jackknife variance formula. These are then averaged

and the new estimate of J is given by J′=2/φ′. The (1−α) confidence interval for  is then

is then

Owing to the idiosyncratic nature of the pseudo-jackknife procedure, it may not correctly account for the correlations between loci as expected. It is even the case that J’ is sometimes higher than J (see Figure 3).

New methods

The limitations of the previous methods directly lead to the application of a standard jackknife technique (Efron and Gong, 1983). The linkage  is

is  recalculated with the ith individual removed from the data set. The mean of these

recalculated with the ith individual removed from the data set. The mean of these  is then taken, that is,

is then taken, that is,

Using a normal distribution for  could be problematic as

could be problematic as  cannot take negative values. One solution is to perform Fisher’s transformation on each of the

cannot take negative values. One solution is to perform Fisher’s transformation on each of the  , that is, take

, that is, take

and their mean to be

Then, a confidence interval for z based on the normal distribution can be constructed as  , that is,

, that is,

where  is the inverse standard normal function evaluated at (α/2) and,

is the inverse standard normal function evaluated at (α/2) and,  , the jackknife standard error (Efron and Gong, 1983) is given by

, the jackknife standard error (Efron and Gong, 1983) is given by

The confidence interval can then be transformed back for  as

as

Computationally, this is quite intensive compared with the previous method; however, the total time for a single estimate is still relatively short.

Although the sample distribution of r2 remains largely unknown (Golding, 1984; Ethier and Griffiths, 1990; Hudson, 2001; Schaid, 2004), there is some theoretical basis (Hill, 1981) that this distribution is approximately χ2 and using a normal distribution for the confidence interval may be an inappropriate approximation. Suppose  can be approximated by

can be approximated by  with J to be determined. Clearly, the mean is matched as one. By matching the variance we again have the ‘best’, J=2/φ,

with J to be determined. Clearly, the mean is matched as one. By matching the variance we again have the ‘best’, J=2/φ,  . To obtain an estimate of φ, we will use the jackknife estimate of the variance

. To obtain an estimate of φ, we will use the jackknife estimate of the variance  and also the jackknife mean

and also the jackknife mean  for the mean

for the mean  . This produces confidence intervals of the form

. This produces confidence intervals of the form

J* is calculated as

It is possible for Equation (2) to produce negative estimates of Ne. Standard practice (Do et al., 2014) is to take these estimates to be infinite. When the upper bound of an estimate is infinite this is equivalent to failing to reject the implicit null hypothesis in the linkage disequilibrium method at a significance level commensurate with the confidence level chosen. The hypothesis is that the population has the same value of r2 as an infinite-sized ideal population–0–and is therefore indistinguishable from it based on the sample estimate. For the purpose of confidence intervals, any negative estimate of Ne is taken to be an extremely high positive number.

Results

It was found that the jackknife systematically overestimated the variance. This is a common issue with jackknife estimates of the variance (Efron and Stein, 1981). It is possible to compensate using a second-order jackknife procedure (Efron and Stein, 1981); however, this becomes computationally intense for large samples sizes. As it appeared that the level of the effect was extremely consistent across the parameter space used for the simulations, a simple empirical correction factor was developed. This factor was arrived at by looking at the unadjusted coverage for the normal distribution method, with Pcrit=0.05 to minimize potential bias, and calculating the normal distribution value for these quantiles. Averaged across all runs, the coverage for the 95% normal confidence intervals was ∼98%, corresponding to a normal distribution value of 2.326, rather than the expected 1.96. That is,

Once the jackknife standard errors were reduced by 0.84, the coverages for both the normal and χ2 variants of the method were much improved. Although the correction factor used is somewhat crude and lacks a theoretical basis, it appears to work consistently across the parameter space of simulated populations.

Once the jackknife standard errors were reduced by 0.84, the coverages for both the normal and χ2 variants of the method were much improved. Although the correction factor used is somewhat crude and lacks a theoretical basis, it appears to work consistently across the parameter space of simulated populations.

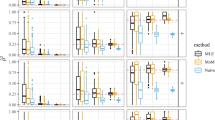

The coverage results for 95% confidence intervals for each of the methods after this adjustment are shown in Figures 1 and 2, as well as Table 1. The newer methods can be more conservative, but their performance does not drop off as the number of comparisons increases as the existing methods do.

The observed coverage probability for nominal 95% confidence intervals plotted against the number of comparisons, J, used in the calculation. No rare alleles are discarded (Pcrit=0). The new methods (filled shapes), although often overconservative, hold up better than the existing ones (hollow shapes) when J is extremely high. Note the log scale on the x axis.

The observed coverage probability for nominal 95% confidence intervals plotted against the number of comparisons, J, used in the calculation. Alleles with observed frequencies <0.05 have been removed (Pcrit=0.05). The performance of the new methods do not drop off as J increases as much as the Pcrit=0 case. This figure corresponds to the data shown in Table 2.

One notable trend that was visible in the data is that as the number of comparisons used in the calculation of  increased, the worse the coverage was. This is to be expected as it is known these are not truly independent and the older jackknife method is only an adjustment to the assumption of independence. Although the newer methods also decline in their performance, the effect is far less drastic. Figures 1 and 2 clearly illustrate this effect. The difference between Figures 1 and 2 is the value of Pcrit used. It can be seen that all methods generally perform better when rare alleles are discarded, but the new methods do not decline in performance as much when Pcrit=0.05.

increased, the worse the coverage was. This is to be expected as it is known these are not truly independent and the older jackknife method is only an adjustment to the assumption of independence. Although the newer methods also decline in their performance, the effect is far less drastic. Figures 1 and 2 clearly illustrate this effect. The difference between Figures 1 and 2 is the value of Pcrit used. It can be seen that all methods generally perform better when rare alleles are discarded, but the new methods do not decline in performance as much when Pcrit=0.05.

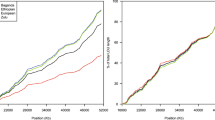

The three methods based on χ2 have an associated number of degrees of freedom. This implicit degrees of freedom value is simply J for the parametric method. For the pseudo-jackknife this is the recalculated value, J’. In the case of the jackknife χ2 it is J*, the value for the degrees of freedom determined from the jackknife variance. The decline in performance of the older methods is likely due to the fact that degrees of freedom used in these confidence intervals are too high. Figure 3 shows that as the number of comparisons increase, the pseudo-jackknife degrees of freedom follows that of the parametric quite closely in a linear relationship, whereas those calculated from the jackknife appear to be proportional to the square root of the number of comparisons. This is likely because of the fact that comparisons between pairs of loci are not all independent, as each will share a locus with a large number of other pairs. It appears that the true degrees of freedom is approximately proportional to the square root of J (Figure 3), rather than the number of comparisons itself. As L and J become very large, we will have  in the order of L instead of J (see example 15.7.1 in Lemann and Romano, 2005). This indicates

in the order of L instead of J (see example 15.7.1 in Lemann and Romano, 2005). This indicates  can be approximated by

can be approximated by  , where J* is in the order of

, where J* is in the order of  or L.

or L.

The number of degrees of freedom calculated for each of the two jackknife methods against the nominal J value taken from the actual number of comparisons. The pseudo-jackknife values appear approximately proportional to the number of comparisons J. The true jackknife values appear to be proportional to the square root of J, a simple linear regression fitted to square root of the implicit degrees of freedom for the true jackknife is shown for illustration (dotted line). In the case of the parametric method the number of degrees of freedom is simply J, and hence the value lies exactly on the top dashed line.

It was found that apart from J and Pcrit, none of the other parameters had a significant effect on the confidence intervals. Results are only shown for a 95% confidence interval but a wide range of α values were examined and the performance does not vary notably between them.

As a rule of thumb, it is recommended that when the number of comparisons (J) is >5000, the newer methods ought to be preferred. Two examples of typical data sets that would exceed this number of comparisons are 110 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; J=5995) and 8 microsatellite loci with 15 alleles each (J=5488). In addition, they may be of use at lower values of J when more conservative confidence intervals are desired or computational time constraints are not an issue.

Discussion

When the number of comparisons used is high, the new confidence interval methods perform better than the methods currently in use, but can be overconservative even when the jackknife variance is corrected.

It should also be possible to introduce an empirical correction based on the trend toward decreasing coverage probability as the number of independent comparisons used to calculate the interval increases, in addition to the uniform reduction of the jackknife variance already applied. This would allow both the overconservative intervals at low values of J and the decline in performance at higher values to be corrected for. However, as this is not the only factor that may affect the coverage accuracy, this would likely overfit the intervals based on limited examples used and thereby reduce robustness.

The newer methods would be of use when making estimates with large numbers of SNPs as J would be extremely high. For 200 SNPs there would be 39 800 comparisons, well into the region where the newer methods perform better. For 2000 SNPs there would be almost 4 million comparisons, well beyond the parameter space explored by this study. However, when large numbers of SNPs are used on unmapped genomes, the amount of physical linkage is unknown and this would likely be of greater concern. One downside of the new methods is the additional computational effort required. Jackknife confidence intervals will take approximately S times longer than the existing methods, where S is the sample size. As the time taken to compute estimates also increases with J, it is likely the extra time may be burdensome in some cases.

The new methods allow one to be very sure of the bounds of an estimate. They would be good to used when certainty is desirable in addition to cases where the number of comparisons used is very large. The normal jackknife technique is preferable over the χ2 jackknife technique as it is simpler and performs almost identically. In spite of the improvements, none of the techniques produce perfect results, and there is a notable amount of unexplained variance in coverage performance, especially in cases where estimates may be biased.

This paper does not look at some other issues that affect estimates of effective population size, such as missing data-related issues. Missing data can arise for a number of reasons. Although the methods used in this paper do employ the standard weighting of subestimates by number of alleles (Waples, 2006; Peel et al., 2013) for variance reduction, it does not include simulated missing data. It is assumed the weightings for this can be applied independently. However, the problems that arise in the confidence intervals as the number of comparisons increases, which is also related to the number of alleles, may mean there is potential for interaction effects between these two factors.

It also does not look at the issue of age-structured populations. Age structure is known to effect point estimates of Ne, and there has been a great deal of recent work in this area (Waples et al., 2011, 2014; Waples and Antao, 2014). It is a possibility that the confidence intervals may also be affected; however, it is unlikely to be the case.

The greatest cause of uncertainty in Ne estimation, Pcrit, is also examined only in part. On the whole, values of Pcrit do not seem to have large effect on confidence interval accuracy, except when J is high. It is likely that a higher number of comparisons can compound the biasing effect of rare alleles. The choice of Pcrit can make a large difference to the conclusions drawn, especially when working with real data sets. When chosen appropriately (Waples and Do (2010) includes a detailed study of the effects of Pcrit level on Ne estimates) it does not appear to significantly impact the coverage accuracy of confidence intervals for any of the methods.

Although the coverage results were reported as a single figure, the split between confidence intervals that fail by being too high and too low are not even. More intervals fail by being too low, rather than too high, across all methods. This occurs in spite of the linkage disequilibrium method having a small upward bias. The mapping of ‘negative’ estimates to infinity skews the distribution; an infinite upper bound is, of course, never too high. It is believed that the distribution of intervals that do not contain the true value are symmetric when considered in terms of r2; however, as the true value of r2 is not as precisely known as that of Ne, this issue remains unclear. Whether or not this issue is of concern in practice would depend on the context.

It is the goal of the authors to incorporate the new methods for generating confidence intervals for the linkage disequilibrium method into a user friendly software package in the future.

Data archiving

The software used in this paper is available at https://github.com/andrewthomasjones/LDNe_CI.

References

Cockerham CC, Weir BS . (1977). Digenic descent measures for finite populations. Genet Res 30: 121–147.

Crow JF, Denniston C . (1988). Inbreeding and variance effective population numbers. Evolution 42: 482–495.

Do C, Waples RS, Peel D, Macbeth G, Tillett BJ, Ovenden JR . (2014). NeEstimator v2: re‐implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Mol Ecol Resour 14: 209–214.

Efron B, Gong G . (1983). A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross-validation. Am Stat 37: 36–48.

Efron B, Stein C . (1981). The jackknife estimate of variance. Ann Stat 9: 586–596.

Ethier S, Griffiths R . (1990). On the two-locus sampling distribution. J Math Biol 29: 131–159.

Golding G . (1984). The sampling distribution of linkage disequilibrium. Genetics 108: 257–274.

Hill WG . (1981). Estimation of effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Genet Res 38: 209–216.

Hudson RR . (2001). Two-locus sampling distributions and their application. Genetics 159: 1805–1817.

Lehmann EL, Romano JP . (2005) Testing Statistical Hypotheses. Springer: New York.

Luikart G, Ryman N, Tallmon DA, Schwartz M, Allendorf F . (2010). Estimation of census and effective population sizes: the increasing usefulness of DNA-based approaches. Conserv Genet 11: 355–373.

Peel D, Waples RS, Macbeth G, Do C, Ovenden JR . (2013). Accounting for missing data in the estimation of contemporary genetic effective population size (Ne). Mol Ecol Resour 13: 243–253.

Peng B, Kimmel M . (2005). simuPOP: a forward-time population genetics simulation environment. Bioinformatics 21: 3686–3687.

Schaid DJ . (2004). Linkage disequilibrium testing when linkage phase is unknown. Genetics 166: 505–512.

Waples RS . (1989). A generalized approach for estimating effective population size from temporal changes in allele frequency. Genetics 121: 379–391.

Waples RS . (2005). Genetic estimates of contemporary effective population size: to what time periods do the estimates apply? Mol Ecol 14: 3335–3352.

Waples RS . (2006). A bias correction for estimates of effective population size based on linkage disequilibrium at unlinked gene loci. Conserv Genet 7: 167–184.

Waples RS, Antao T . (2014). Intermittent breeding and constraints on litter size: consequences for effective population size per generation (Ne) and per reproductive cycle (Nb). Evolution 68: 1722–1734.

Waples RS, Antao T, Luikart G . (2014). Effects of overlapping generations on linkage disequilibrium estimates of effective population size. Genetics 197: 769–780.

Waples RS, Do C . (2008). LDNE: a program for estimating effective population size from data on linkage disequilibrium. Mol Ecol Resour 8: 753–756.

Waples RS, Do C . (2010). Linkage disequilibrium estimates of contemporary Ne using highly variable genetic markers: a largely untapped resource for applied conservation and evolution. Evol Appl 3: 244–262.

Waples RS, Do C, Chopelet J . (2011). Calculating Ne and Ne/N in age-structured populations: a hybrid Felsenstein-Hill approach. Ecology 92: 1513–1522.

Waples RS, Faulkner JR . (2009). Modelling evolutionary processes in small populations: not as ideal as you think. Mol Ecol 18: 1834–1847.

Waples RS, Gaggiotti O . (2006). INVITED REVIEW: What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity. Mol Ecol 15: 1419–1439.

Weir BS . (1979). Inferences about linkage disequilibrium. Biometrics 35: 235–254.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robin Waples for his advice with regard to the determination of the true effective population size from a particular realization of a simulation. We also thank him and two other anonymous reviewers for their suggestions on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, A., Ovenden, J. & Wang, YG. Improved confidence intervals for the linkage disequilibrium method for estimating effective population size. Heredity 117, 217–223 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.19

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.19

This article is cited by

-

The genetic status and rescue measure for a geographically isolated population of Amur tigers

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Microsatellites and mitochondrial evidence of multiple introductions of the invasive raccoon Procyon lotor in France

Biological Invasions (2023)

-

Inferring inter-colony movement within metapopulations of yellow-footed rock-wallabies using estimates of kinship

Conservation Genetics (2023)

-

Population genomics study for the conservation management of the endangered shrub Abeliophyllum distichum

Conservation Genetics (2022)

-

The paradox of retained genetic diversity of Hippocampus guttulatus in the face of demographic decline

Scientific Reports (2021)