Abstract

Telomeres are emerging as a biomarker for ageing and survival, and are likely important in shaping life-history trade-offs. In particular, telomere length with which one starts in life has been linked to lifelong survival, suggesting that early telomere dynamics are somehow related to life-history trajectories. This result highlights the importance of determining the extent to which telomere length is inherited, as a crucial factor determining early life telomere length. Given the scarcity of species for which telomere length inheritance has been studied, it is pressing to assess the generality of telomere length inheritance patterns. Further, information on how this pattern changes over the course of growth in individuals living under natural conditions should provide some insight on the extent to which environmental constraints also shape telomere dynamics. To fill this gap partly, we followed telomere inheritance in a population of king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus). We tested for paternal and maternal influence on chick initial telomere length (10 days old after hatching), and how these relationships changed with chick age (at 70, 200 and 300 days old). Based on a correlative approach, offspring telomere length was positively associated with maternal telomere length early in life (at 10 days old). However, this relationship was not significant at older ages. These data suggest that telomere length in birds is maternally inherited. Nonetheless, the influence of environmental conditions during growth remained an important factor shaping telomere length, as the maternal link disappeared with chicks’ age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Telomeres are highly conserved non-coding repetitive DNA sequences capping the ends of chromosomes and preventing them from being recognized as double-stranded breaks. Once telomeres reach a lower critical length, cell division arrest and/or cell senescence occurs (Blackburn, 2001). The rate at which telomeres shorten, therefore, defines cellular and organismal ageing, and depends on the balance between proeroding factors (such as oxidative stress or rate of cell division) and antieroding factors (such as the enzyme telomerase, mainly in germinal and stem cells, that actively rebuilds lost telomeres; Blackburn, 2001). Telomere length is also partly regulated by the telomere-associated shelterin protein complex (De Lange, 2005), and has consequently previously been defined as a polygenic trait (Andrew et al., 2006; Gatbonton et al., 2006).

Currently, emphasis is placed upon characterizing the extent to which variation in telomere loss might reflect life-history trade-offs and be involved in the evolution of life histories (Monaghan and Haussmann, 2006). For instance, telomere length at the end of growth has been found to predict accurately individual life expectancy both in captivity (Heidinger et al., 2012) and in the wild (Bize et al., 2009). Then, telomeres may be important life-history markers determining how much can be invested in maintenance efforts over the course of life (Eisenberg, 2011), ‘powerfully quantifying life’s insults’ (Blackburn and Epel, 2012), and constituting a potential proxy of future individual fitness in a large variety of species from humans to birds (Cawthon et al., 2003; Heidinger et al., 2012). Therefore, telomere dynamics might be potential indicators of individual quality and could provide an insight into ecology and evolutionary biology.

Only traits with interindividual variation are of importance in evolution and are shaped by natural selection. Therefore, transmission and heritability (i.e. genetic and environmental variability in inheritance, estimated as the genetically based variation of inheritance expressed by h2) of morphologic (Voillemot et al., 2012), physiologic and behavioural traits, as well as ultimate fitness, have been widely studied (Kruuk et al., 2000). It remains then important to check inheritance of fitness-related traits, lifespan in our case and of the mechanisms susceptible to shape them. Telomere length is highly variable among age-matched individuals (a trait suggested to have an early-life origin; (Hall et al., 2004). Given significant heritability, telomere length variability is likely to provide a matrix for natural selection to act upon. Indeed, if telomere length is related to intrinsic trade-offs, phenotypes able to cope with (prevent) telomere erosion, thus repairing time and stress insults, may be at a selective advantage. The idea that ageing mechanisms may be partly inherited is supported by recent results in lizards, showing that ROS production (a proerosion factor for telomeres) is inherited from mothers to offspring (Olsson et al., 2008).

At present however, knowledge on telomere length inheritance patterns, telomere length heritability and on the effects of parental age on telomere length in animals remains scarce. Those data are mainly restricted to humans (Nawrot et al., 2004; Nordfjäll et al., 2005, 2009; Unryn et al., 2005; Njajou et al., 2007), with results from studies on monozygotic and dizygotic twins (Slagboom et al., 1994; Graakjaer et al., 2004) (see Table 1 for a review). Most of these studies support paternal inheritance of telomere length (Nordfjäll et al., 2005, 2009; Njajou et al., 2007), further revealing that paternal age is a strong determinant of offspring telomere length (Unryn et al., 2005; De Meyer et al., 2007; Kimura et al., 2008; Eisenberg, 2011). Interestingly, in non-human species contrasting results reveal either bi-parental inheritance patterns, for example, male inheritance in lizards (Olsson et al., 2011) or maternal inheritance in birds (females being ZW; Horn et al., 2011). These studies report highly variable heritability estimates ranging from 0.18 to >1.

Determining telomere length inheritance pattern is an important step in understanding the putative role of telomeres in lifespan variability. Given the scarcity of species for which telomere length inheritance has been studied (see Table 1), it is pressing to assess the generality of inheritance patterns in a broad range of species, in particular in wild populations. Further, there is an urgent need to test to which extent telomere inheritance patterns are maintained over growth, which should provide some insight into how far environmental constraints blur our perception of telomere length inheritance.

Consequently, we provide a case study of telomere length inheritance patterns in wild king penguins (A. patagonicus), a species where breeding parents raise a single chick that can be sampled early in life and followed over an 11-month-long growth period. We have previously shown that over this extended growth period, environmental challenges such as a prolonged winter fast, may have a tremendous impact on chick telomere loss (Geiger et al., 2012). Here, we test for paternal and maternal influences on chick starting telomere length, and investigate how these relationships change over time as chicks age. Our protocol should allow distinguishing between genetic and environmental influences shaping telomere length in this long-lived seabird.

Materials and methods

Study site and animal model

This study was conducted on king penguins (A. patagonicus), in the colony of ‘La Grande Manchotière’ (20 000 breeding pairs) Possession island, Crozet archipelago (Terres Australes Antarctiques Françaises) located 46°25′S; 51°52′E. Data were collected during two consecutive field seasons (2009 and 2010).

The king penguin is a long-lived, pelagic seabird with a unique life cycle. The entire annual breeding cycle of adults lasts 14–16 months (including moult; Weimerskirch et al., 1992) during which parents alternate between attending the chick on land and foraging at sea. In the middle of their growth period, chicks face 3 months of sub-Antarctic winter by their own, with a reduced food supply by the parents. Consequently, the entire growth period of chicks spreads over 11 months before they finally moult into subadult plumage and depart to sea (Weimerskirch et al., 1992).

General procedures

We followed 53 breeding pairs and started chick monitoring as close as possible to hatching, that is, 10 days afterwards to avoid breeding failure. Chicks were individually identified with fishtags and followed from hatching to the beginning of the final moult.

Chick telomere length dynamics was studied from blood samples collected from the marginal flipper vein at 10 (number of chicks=53), 70 (n=37), 200 (n=34) and 300 days old (n=30). During blood sampling, the chick’s head was always covered with a hood to reduce its stress. Our sample size decreased over time owing to the fact that not all chicks survived the growth period (causes of death, likely predation, were not determined but were unrelated to handling). To investigate a potential link between parent and chick telomere length, brooding fathers were sampled when the chicks were 10 days old. Mothers were sampled at the next brooding shift, when they returned to the colony to relieve their partner some 15 days later (Descamps et al., 2002). All blood samples were stored at −80 °C until analyses.

Telomere length measurements

Telomere length measurements were carried out when the chicks were 10, 70, 200 and 300 days. Telomere length was measured in DNA extracted from red blood cells (stored at −80 °C until analysis), which are nucleated in birds) using a Nucleospin Blood QuickPure Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren Germany). Telomere length was assessed by quantitative real-time amplification (qPCR) (Cawthon, 2002), a procedure previously described in birds (Bize et al., 2009; Criscuolo et al., 2009), including in king penguins (Geiger et al., 2012). Relative telomere length is expressed as the (T/S) ratio of telomere repeat copy number (T) to a control single copy number gene (S). We used the A. patagonicus zinc-finger protein as a single control gene. Forward and reverse primers for the zinc-finger protein gene were 5′-TACATGTGCCATGGTTTTGC-3′ and 5′-AAGTGCTGCTCCCAAAGAAG-3′, respectively. Telomere primers were: Tel1b (5′-CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT-3′) and Tel2b (5′-GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT-3′). qPCR for both telomere and the zinc-finger protein was performed using 2.5 ng of DNA with sets of primers Tel1b/Tel2b (or zinc-finger protein-F/zinc-finger protein-R), in a final volume of 10 μl containing 5 μl of BRYT Green fluorescent dye (GoTaqqPCR Master Mix; Promega, Charbonnieres les Bains, France). Primer concentrations in the final mix were 200 nM for telomere length determination and 300 nM for the control gene. Telomere and control gene PCR conditions were: 2 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 56 °C, 30 s at 72 °C and 60 s at 95 °C. Telomere and control (i.e. non-variable in copy number) gene amplification of each sample were carried out on the same plate. Each plate included serial dilutions (telomere and control gene, 5, 2.5, 1.25 and 0.625 ng) of DNA of the same reference bird which were run in triplicate. These serial dilutions were used to generate a reference curve on each plate, to control for the amplifying efficiency of the qPCR (both telomere and control gene). Mean amplification efficiency calculated from the reference curves of the qPCR runs were comprised between 100.9 and 103.1 (telomere) and 100.6 and 102.9 (control gene). R2 calculated from the reference curves of the qPCR runs were comprised between 0.96–0.99 (telomere) and 0.97–0.99 (control gene). Intraplate mean coefficients of variation for Ct values were 1.35±0.06% (telomere assay) and 0.79±0.04% (control gene assay). Interplate coefficients of variation based on repeated samples were 1.56% (telomere assay) and 1.35% for (control gene assay). Mean coefficient of variation for the relative T/S ratios was 16%. To take into account the slight variation of efficiencies (E) between telomere and control gene amplifications, we calculated relative telomere length as: relative T/S ratios=((1+E telomere)^ΔCt telomere (control−sample)/(1+E control gene)^ΔCt control gene (control−sample)) (see Pfaffl, 2001). Both a negative control (water) and melting curves were run for each plate to check for nonspecific amplification and primer–dimer artefacts.

Sex determination was carried out using DNA extracted from red blood cells. The method was adapted from (Griffiths et al., 1998): 80 ng of DNA in a final volume of 20 μl, the PCR conditions were 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 10 cycles of a touchdown protocol: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C (reducing the temperature of this step by 1 °C at each cycle), 35 s at 72 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 50 °C and 35 s at 72 °C, finished by 5 min at 72 °C.

Statistical analysis

Telomere length (dependent variable) was log transformed to achieve a normal distribution and homoscedasticity. We assessed the time effect on telomere length using a generalized estimating equation (GEE). The time period (which corresponds to the different times of sampling during the growth period: 10, 70, 200 and 300 days posthatching) was entered as a repeated variable in the model, chick identity as a random factor, and chick sex, year of sampling, maternal and paternal telomere length as independent variables. All interactions between the different variables were tested. Nonsignificant interactions were removed sequentially from the analysis, starting with the least significant.

Then, to assess whether mother–offspring and father–offspring regressions were significantly different, we used a GEE with chick telomere length as the dependent variable. As before, time period was entered (10, 70, 200 and 300 days) as a repeated variable, chick identity as a random factor and parents’ sex, telomere length and the interaction between parent’s sex and telomere length as independent variables in the model

Finally, even though the interactions between parent’s telomere lengths and the time period were not significant, we further tested for a potential link between chicks’ telomere length and parents’ telomere lengths over time by conducting a more exploratory analysis using Pearson’s correlations. This link was tested at the four different chick ages.

The slopes of the regressions between both mid-parental and offspring telomere lengths, and between maternal and offspring telomere lengths were used to estimate narrow sense heritability: h2 (the proportion of the phenotypic variance that is explained by additive genetic variance). To assess whether the mother–offspring h2 was significantly different from the father–offspring one, we used a GEE with offspring telomere length as a dependent variable, chick identity as a random factor, parents’ sex, telomere length and the interaction between parent’s sex and telomere length as independent variables in the model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)). Significance level was set at 5%.

Results

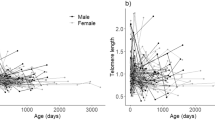

We found no sex or year effect on chick telomere length (Table 2, P=0.57 and 0.82, respectively). However, there was a significant effect of the time period on offspring telomere length (Figure 1 and Table 2, P<0.001), suggesting that telomeres were progressively eroded over the growth period (means values±s.e.: 10 days (0.107±0.02); 70 days (0.064±0.024); 200 days (−0.06±0.025); 300 days (0.012±0.026)). In contrast to paternal telomere length, maternal telomere length was significantly related with chick telomere length (Table 2, P=0.028).

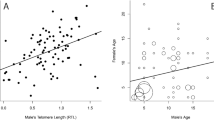

Chick telomere lengths at 10 days were significantly correlated to maternal telomere length (Figure 2 and Table 3, P=0.042), but not to paternal telomere length (Figure 3 and Table 3, P=0.388). However, the homogeneity of slope test showed no significant effect of the interaction between parent sex and parent telomere length (Table 4, P=0.513), indicating that the mother–offspring and father–offspring slopes were not significantly different.

Heritability calculated using the slope of the regression between offspring and mean parents’ telomere lengths was of 0.2 (s.e 0.110), and was of 0.2 (s.e. 0.096) for the regression between offspring and maternal telomere lengths. The homogeneity of slope test used to assess whether mother–offspring and father–offspring h2 were significantly different showed no significant effect of the interaction between parent sex and parent telomere length (Wald χ2=0.875, P=0.350). This indicates that the mother–offspring and father–offspring h2 were not significantly different.

Offspring telomere lengths at 70, 200 and 300 days were not significantly correlated to maternal or paternal telomere length (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study shows that maternal and offspring telomere lengths are interrelated in the king penguin. However, our exploratory correlative analysis indicated that this link was displayed during early life (10 days) only, and found to become weaker (and nonsignificant) as chicks grew older. This result may be partly explained by selective mortality, chicks with short telomeres likely disappearing faster from the population (Geiger et al., 2012). As these short telomere chicks were sampled only at 10 days, they may have produced enough variance in our sample to detect the significant correlation we observe at 10 days, but not later on. However, using only chicks that stayed alive for the entire experiment, the correlation remained significant at day 10 (r2=0.14, P=0.038, n=30, mother–offspring h2 of 0.2 (s.e. 0.1), midparental–offspring h2 of 0.3 (s.e. 0.1)).

Moreover, maternal telomere length was linked to offspring telomere length, whereas paternal telomere length was not. Yet, we found no significant difference between father–offspring and mother–offspring correlations. Therefore, paternal heritability of telomere length in this species might not be totally excluded, as it may have been masked by the difference in the age of sampling between chicks and their parents. Indeed, results might have been different had we sampled the parents when they were chicks.

Nonetheless, our findings are in accordance with previous data collected on the kakapo (Horn et al., 2011), showing maternal inheritance of telomere length in birds. The pattern of telomere length inheritance displayed in birds seems to mirror the one found in several human studies (Nordfjäll et al., 2005, 2009; Njajou et al., 2007) and suggests that the heterogametic sex might have a key role in offspring telomere length determination.

Gene imprinting may be one of the mechanisms explaining why telomere inheritance is done through heterogamy. Imprinting occurs when both maternal and paternal alleles are present and one allele is expressed while the other remains silent (Pfeifer, 2000). Usually, the imprint marks distinguishing the parental alleles are epigenetic and generally due to DNA methylation and histone modifications, which can alter transcription patterns, and restrict gene expression (Pfeifer, 2000). To date, very few studies have identified imprinting of telomere length-regulating genes. Recently, Gao et al. (2011) identified a paternal imprinting on sperm chromatin that is essential for the inheritance of telomere identity in Drosophila malanogaster. Other studies determined that nucleotide polymorphisms occur in a large number of loci that code for proteins regulating DNA and histone methylation are associated with telomere length variability in humans (Gatbonton et al., 2006; Blasco, 2007a). Therefore, a possibility would be that imprinting mechanisms might regulate expression of genes modulating telomere length (genes coding for telomerase and shelterin proteins), thus explaining the different patterns of telomere length inheritance observed. The regulation of telomere length by epigenetic factors (Blasco, 2007a) also supports the idea that imprinting mechanisms might be involved in telomere length inheritance. Indeed, histone modifications and DNA methylation seem to act as negative regulators of telomere length in humans/mice (García-Cao et al., 2004; Gonzalo et al., 2006). Epigenetic factors are known to impact directly telomere length, and also to regulate telomerase activity (Cong et al., 2002). The hTERT gene promoter has been reported, as a rare exception, to be upregulated by methylation (Shin et al., 2003; Nordfjäll et al., 2005). Overall, it underlines that different pathways (from DNA and histone state to telomere maintenance protein expression) are likely to regulate telomere length inheritance (Blasco, 2007a).

Even though most studies conducted in humans suggest a paternal inheritance of telomere length (i.e. the mammalian heterogametic sex) (Nordfjäll et al., 2005, 2009; Njajou et al., 2007), some of them suggest that maternal inheritance also occurs (Nawrot et al., 2004; Broer et al., 2013; Eisenberg, 2013). As recently pointed out by Eisenberg (2013), the fact that some studies point to stronger father–offspring correlations, whereas others to stronger mother–offspring correlations is unlikely to be ascribed only to statistical noise, and at present no conclusion may be drawn.

These contrasting results indicate that the implication of the heterogametic sex is less straightforward than initially hypothesized. Indeed, the heterogametic pattern of telomere length inheritance observed in most studies might also be the result of confounding factors such as parental effects. Alternatively, it might be due to the fact that the link with the non-heterogametic sex is too weak to be detected. Investigation of telomere length inheritance patterns in more species (in complement to mammals and birds) with different sex determination systems, such as haplodiploidy and environmental sex determination (i.e. temperature dependent), might help solve whether telomere length is determined by the heterogametic sex.

Besides telomere length inheritance, some studies cited in Table 1 consider with more depth telomere length heritability, attempting to disentangle additive, non-additive genetic and environmental variability in inheritance patterns. Studies in humans reported heritability estimates of telomere length between 0.44 and 0.78 (Slagboom et al., 1994; Njajou et al., 2007) and of 0.52–1.23 in other vertebrates such as the sand lizards (Lacerta agilis), with an interesting difference in sex-specific heritability (Olsson et al., 2011; see Table 1). However, these estimations were carried out mainly using mid-parent–offspring regressions (or comparisons between relatives) that may yield high heritability values (Conner and Hartl, 2004). Data on humans have led to the conclusion that individual variation in telomere length mainly originates from differences in the zygote and that epigenetic/environmental influences are relatively weak (Graakjaer et al., 2004).

Nonetheless, a powerful approach to untangle genetic vs environmental effects is to use animal models with known genealogies or necessitates a cross-fostering design (Voillemot et al., 2012). Chick exchange between nests was recently used in a wild population of collared flycatchers (Voillemot et al., 2012). Heritability of telomere length (the proportion of the phenotypic variance explained by additive genetic variance) was found to be 0.18 (and not 9% as reported previously; P Bize, personal communication), a value close to the one we found here in king penguins (maternal estimate of h2=0.2; mid-parent estimate of h2=0.2), and supports the idea that additive-genetic effect is low in these two species. There are alternative explanations of these low heritability values. The first is that environmental factors are important determinants of early-life telomere length (Monaghan and Haussmann, 2006). Indeed, we found that the link between offspring and maternal telomere length early in life (10 days) was not maintained at a significant level over the growth period. Even if this result must be taken with caution as based on correlations established from a decreasing sample size with age, it partly supports that environmental factors have a strong influence on telomere loss in king penguin chicks (see Voillemot et al., 2012). Further, Geiger et al. (2012) showed that faster-growing king penguin chicks loose telomere at a higher rate, illustrating the potential importance of early growth conditions on telomere dynamics. Such effects may have masked the link between offspring and maternal telomere lengths as chicks aged. Second, because telomere length is related to individual fitness (Bauch et al., 2013), it is possible that natural selection has tended to deplete genetic variation of the loci-regulating telomere length in early life, thereby depleting the additive-genetic effect (Mirabello et al., 2012). Finally, telomeres have been defined as a polygenic trait (Andrew et al., 2006; Gatbonton et al., 2006). As there are many more interactions possible between a greater number of loci (Lynch and Walsh, 1998), a third possibility could be that the non-additive genetic component of residual variance is large, thereby decreasing heritability but not because of additive-genetic variability depletion (Merilä and Sheldon, 1999). We could hypothesize that the pattern of telomere length heredity is dependent on the inheritance pattern of multiple telomere length restoration/maintenance factors (Blackburn, 2001; Blasco, 2007b). A resetting mechanism of early-life telomere length has been pointed out in mammals, in which both telomerase activity and parent telomere length are interacting to set-up the embryo starting telomere length (Chiang et al., 2010). Focusing on these processes in the future might enable us to better understand how progressive telomere shortening over generations is avoided and how interspecific variability in telomere dynamics may have evolved.

Owing to the absence of siblings in our study, testing these alternatives was not possible. Still, a longitudinal following of the same breeders over years might enable us to estimate the additive and non-additive genetic components of transmitted telomere length (i.e. relative telomeres comparisons). Even more interesting is the fact that, due to the long development duration of their chick, king penguin alternatively breeds early or late in the season, depending on the fact that they were successful the preceding year (Weimerskirch et al., 1992). Late breeders likely reproduce in a more stressful ecologic environment, because of a higher density of breeders later in the season (Viblanc et al., 2011, 2014). Comparisons of the same pairs, during successive early and late breeding attempts, may enable us to estimate components of residual variance in telomere length such as ecological inheritance.

In conclusion, our study confirms that telomere length is maternally inherited in birds, supporting the hypothesis of inheritance from the heterogametic sex, and suggests strong environmental effects on telomere dynamics, as this link disappeared over time. However, in view of the present knowledge (Table 1), the results on telomere length inheritance and heritability patterns are still contrasted. For a better understanding of telomere length transmission, future works should focus on the whole balance (i.e. pro- and antierosion factors and their inheritance) that is going to shape the offspring telomere length, to understand accurately how telomeres are transmitted over generations. State may be as important as length in this case.

Data archiving

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: doi:10.5061/dryad.4407g.

References

Al-Attas OS, Al-Daghri NM, Alokali MS, Alkharfy KM, Alfadda AA, McTernan P et al. (2012). Circulating leukocyte telomere length is highly heritable among families of Arab descent. BMC Medical Genetics 13: 38.

Andrew T, Aviv A, Falchi M, Surdulescu GL, Gardner JP, Lu X et al. (2006). Mapping genetic loci that determine leukocyte telomere length in a large sample of unselected female sibling pairs. Am J Hum Genet 78: 480–486.

Bauch C, Becker PH, Verhulst S . (2013). Telomere length reflects phenotypic quality and costs of reproduction in a long-lived seabird. Proc Biol Sci R Soc 280: 20122540.

Bischoff C, Graakjaer J, Petersen HC, Hjelmborg JVB, Vaupel JW, Bohr V et al. (2005). The heritability of telomere length among the elderly and oldest-old. Twin Res Hum Genet 8: 433–439.

Bize P, Criscuolo F, Metcalfe NB, Nasir L, Monaghan P . (2009). Telomere dynamics rather than age predict life expectancy in the wild. Proc R Soc Ser B 276: 1679–1683.

Blackburn EH . (2001). Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106: 661–673.

Blackburn EH, Epel ES . (2012). Telomeres and adversity: too toxic to ignore. Nature 490: 169–171.

Blasco MA . (2007a). The epigenetic regulation of mammalian telomeres. Nat Rev Genet 8: 299–309.

Blasco MA . (2007b). Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol 3: 640–649.

Broer L, Codd V, Nyholt DR, Deelen J, Mangino M, Willemsen G et al. (2013). Meta-analysis of telomere length in 19 713 subjects reveals high heritability, stronger maternal inheritance and a paternal age effect. Eur J Hum Genet 21: 1163–1168.

Cawthon RM . (2002). Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e47.

Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O'Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA . (2003). Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet 361: 393–395.

Chiang YJ, Calado RT, Hathcock KS, Lansdorp PM, Young NS, Hodes RJ . (2010). Telomere length is inherited with resetting of the telomere set-point. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10148–10153.

Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW . (2002). Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 66: 407–425.

Conner JK, Hartl DL . (2004) A Primer of Ecological Genetics Sinauer Associates Incorporated.

Criscuolo F, Bize P, Nasir L, Metcalfe NB, Foote CG, Griffiths K et al. (2009). Real-time quantitative PCR assay for measurement of avian telomeres. J Avian Biol 40: 342–347.

De Lange T . (2005). Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19: 2100–2110.

De Meyer T, Rietzschel ER, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer D, Van Criekinge W, De Backer GG et al. (2007). Paternal age at birth is an important determinant of offspring telomere length. Hum Mol Genet 16: 3097–3102.

Descamps S, Gauthier-Clerc M, Gendner J-P, Le Maho Y . (2002). The annual breeding cycle of unbanded king penguins Aptenodytes patagonicus on Possession Island (Crozet). Avian Sci 2: 87–98.

Eisenberg DT . (2013). Inconsistent inheritance of telomere length (TL): is offspring TL more strongly correlated with maternal or paternal TL&quest. Eur J Hum Genet 22: 8–9.

Eisenberg DTA . (2011). An evolutionary review of human telomere biology: the thrifty telomere hypothesis and notes on potential adaptive paternal effects. Am J Hum Biol 23: 149–167.

Eisenberg DT, Hayes MG, Kuzawa CW . (2012). Delayed paternal age of reproduction in humans is associated with longer telomeres across two generations of descendants. Proc Nat Acad Sci 109: 10251–10256.

Gao G, Cheng Y, Wesolowska N, Rong YS . (2011). Paternal imprint essential for the inheritance of telomere identity in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa 108: 4932–4937.

García-Cao M, O'Sullivan R, Peters AHFM, Jenuwein T, Blasco MA . (2004). Epigenetic regulation of telomere length in mammalian cells by the Suv39h1 and Suv39h2 histone methyltransferases. Nat Genet 36: 94–99.

Gatbonton T, Imbesi M, Nelson M, Akey JM, Ruderfer DM, Kruglyak L et al. (2006). Telomere length as a quantitative trait: genome-wide survey and genetic mapping of telomere length-control genes in yeast. PLoS Genet 2: e35.

Geiger S, Le Vaillant M, Lebard T, Reichert S, Stier A, Le Maho Y et al. (2012). Catching-up but telomere loss: half-opening the black box of growth and ageing trade-off in wild king penguin chicks. Mol Ecol 21: 1500–1510.

Gonzalo S, Jaco I, Fraga MF, Chen T, Li E, Esteller M et al. (2006). DNA methyltransferases control telomere length and telomere recombination in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 8: 416–424.

Graakjaer J, Pascoe L, Der-Sarkissian H, Thomas G, Kolvraa S, Christensen K et al. (2004). The relative lengths of individual telomeres are defined in the zygote and strictly maintained during life. Aging Cell 3: 97–102.

Griffiths R, Double MC, Orr K, Dawson RJG . (1998). A DNA test to sex most birds. Mol Ecol 7: 1071–1075.

Hall ME, Nasir L, Daunt F, Gault EA, Croxall JP, Wanless S et al. (2004). Telomere loss in relation to age and early environment in long-lived birds. Proc R Soc Ser B 271: 1571–1576.

Heidinger BJ, Blount JD, Boner W, Griffiths K, Metcalfe NB, Monaghan P . (2012). Telomere length in early life predicts lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 1743–1748.

Horn T, Robertson BC, Will M, Eason DK, Elliott GP, Gemmell NJ . (2011). Inheritance of telomere length in a bird. PLoS ONE 6: e17199.

Jeanclos E, Schork NJ, Kyvik KO, Kimura M, Skurnick JH, Aviv A . (2000). Telomere length inversely correlates with pulse pressure and is highly familial. Hypertension 36: 195–200.

Kimura M, Cherkas LF, Kato BS, Demissie S ., Hjelmborg JB, Brimacombe M et al. (2008). Offspring's leukocyte telomere length, paternal age, and telomere elongation in sperm. PLoS Genet 4: e37.

Kruuk LEB, Clutton-Brock TH, Slate J, Pemberton JM, Brotherstone S, Guinness FE . (2000). Heritability of fitness in a wild mammal population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 698–703.

Lynch M, Walsh B . (1998) Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

Merilä J, Sheldon BC . (1999). Genetic architecture of fitness and nonfitness traits: empirical patterns and development of ideas. Heredity 83: 103–109.

Mirabello L, Yeager M, Chowdhury S, Qi L, Deng X, Wang Z et al. (2012). Worldwide genetic structure in 37 genes important in telomere biology. Heredity 108: 124–133.

Monaghan P, Haussmann MF . (2006). Do telomere dynamics link lifestyle and lifespan? Trends Ecol Evol 21: 47–53.

Nawrot TS, Staessen JA, Gardner JP, Aviv A . (2004). Telomere length and possible link to X chromosome. Lancet 363: 507–510.

Njajou OT, Cawthon RM, Damcott CM, Wu SH, Ott S, Garant MJ et al. (2007). Telomere length is paternally inherited and is associated with parental lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12135–12139.

Nordfjäll K, Larefalk Å, Lindgren P, Holmberg D, Roos G . (2005). Telomere length and heredity: Indications of paternal inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16374–16378.

Nordfjall K, Svenson U, Norrback K-F, Adolfsson R, Roos G . (2009). Large-scale parent–child comparison confirms a strong paternal influence on telomere length. Eur J Hum Genet 18: 385–389.

Olsson M, Pauliny A, Wapstra E, Uller T, Schwartz T, Blomqvist D . (2011). Sex differences in sand lizard telomere inheritance: paternal epigenetic effects increases telomere heritability and offspring survival. PLoS ONE 6: e17473.

Olsson M, Wilson M, Uller T, Mott B, Isaksson C, Healey M et al. (2008). Free radicals run in lizard families. Biol Lett 4: 186–188.

Pfaffl MW . (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45.

Pfeifer K . (2000). Mechanisms of genomic imprinting. Am J Hum Genet 67: 777–787.

Shin KH, Kang MK, Dicterow E, Park NH . (2003). Hypermethylation of the hTERT promoter inhibits the expression of telomerase activity in normal oral fibroblasts and senescent normal oral keratinocytes. Br J Cancer 89: 1473–1478.

Slagboom PE, Droog S, Boomsma DI . (1994). Genetic determination of telomere size in humans: a twin study of three age groups. Am J Hum Genet 55: 876–882.

Unryn BM, Cook LS, Riabowol KT . (2005). Paternal age is positively linked to telomere length of children. Aging Cell 4: 97–101.

Vasa-Nicotera M, Brouilette S, Mangino M, Thompson JR, Braund P, Clemitson JR et al. (2005). Mapping of a major locus that determines telomere length in humans. Am J Hum Genet 76: 147–151.

Viblanc VA, Gineste B, Stier A, Robin J-P, Groscolas R . (2014). Stress hormones in relation to breeding status and territory location in colonial king penguin: a role for social density? Oecologia 175: 763–772.

Viblanc VA, Mathien A, Saraux C, Viera VM ., Groscolas R . (2011). It costs to be clean and fit: energetics of comfort behavior in breeding-fasting penguins. PLoS ONE 6: e21110.

Voillemot M, Hine K, Zahn S, Criscuolo F, Gustafsson L, Doligez B et al. (2012). Effects of brood size manipulation and common origin on phenotype and telomere length in nestling collared flycatchers. BMC Ecol 12: 17.

Weimerskirch H, Stahl JC, Jouventin P . (1992). The breeding biology and population dynamics of king penguins Aptenodytes patagonica on the Crozet Islands. Ibis 134: 107–117.

Acknowledgements

We thank the French Polar Institut (IPEV) for providing financial support for this study, Yvon Le Maho and Céline Le Bohec for allowing collaboration between IPEV scientific programs (119–137) and all the field assistants that worked partially on this project (Marion Kauffmann, Marion Ripoche, Laetitia Kernaleguen, Benoit Gineste and all the others among which the logistic teams of the Alfred Faure base). We also thank Hélène Gachot for the sex determination analyses, Antoine Stier and Vincent Viblanc for helpful discussions and proofreading the manuscript. All procedures were approved by an independent ethics committee commissioned by the French Polar Institute. Working in the colony, handling chicks and sampling was allowed by Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises (TAAF). The experiments comply with the current laws of France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reichert, S., Rojas, E., Zahn, S. et al. Maternal telomere length inheritance in the king penguin. Heredity 114, 10–16 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2014.60

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2014.60

This article is cited by

-

Bovine telomere dynamics and the association between telomere length and productive lifespan

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Shorter telomeres precede population extinction in wild lizards

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Age at maturation has sex- and temperature-specific effects on telomere length in a fish

Oecologia (2017)

-

The relationship of telomere length to baseline corticosterone levels in nestlings of an altricial passerine bird in natural populations

Frontiers in Zoology (2016)

-

Embryonic and postnatal telomere length decrease with ovulation order within clutches

Scientific Reports (2016)