Abstract

Allopatric speciation often yields ecologically equivalent sister species, so that their secondary admixis enforces competition. The shores of Lake Tanganyika harbor about 120 distinct populations of the cichlid genus Tropheus, but only some are sympatric. When alone, Tropheus occupies a relatively broad depth zone, but in sympatry, fish segregate by depth. To assess the effects of competition, we studied the partial co-occurrence of Tropheus moorii ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’ with Tropheus polli. A previous study demonstrated via standardized breeding experiments that some observed differences between Tropheus ‘Kaiser’ living alone and in sympatry with T. polli have a genetic basis despite large-scale phenotypic plasticity. Using geometric morphometrics and neutral genetic markers, we now investigated whether sympatric populations differ consistently in body shape from populations living alone and if the differences are adaptive. We found significant differences in mean shape between non-sympatric and sympatric populations, whereas all sympatric populations of both color morphs clustered together in shape space. Sympatric populations had a relatively smaller head, smaller eyes and a more anterior insertion of the pectoral fin than non-sympatric populations. Genetically, however, non-sympatric and sympatric ‘Kaiser’ populations clustered together to the exclusion of ‘Kirschfleck’. Genetic distances, but not morphological distances, were correlated with geographic distances. Within- and between-population covariance matrices for T. moorii populations deviated from proportionality. It is thus likely that natural selection acts on both phenotypic plasticity and heritable traits and that both factors contribute to the observed shape differences. The consistency of the pattern in five populations suggests ecological character displacement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phenotypic variation among individuals is produced by the combined effect of phenotypic plasticity and genetically based differences. Alternative phenotypes are subject to natural selection, no matter the source, leading to adaptive evolution at the population level (Via and Lande, 1985). Thus, variation in morphology constitutes a co-gradient, with environmental effects on phenotypic expression reinforcing or counteracting genetic differences between populations (Marcil et al., 2006). Novel traits can originate by environmental induction as well as mutation, to subsequently undergo selection and genetic accommodation. It has been argued that adaptive innovation owing to developmental plasticity may have greater evolutionary potential than mutationally induced ones (West-Eberhard, 2005a). In this respect, a timely theory of adaptive evolution must recognize the importance of phenotypic accommodation, that is, the refinement of the adaptive phenotype through subsequent mutational changes (Suzuki and Nijhout, 2006), in addition to selection operating on novel features arising from random variation owing to mutation (West-Eberhard, 2005b). The factors promoting or limiting plasticity in a given population, however, might be difficult to demonstrate (DeWitt et al., 1998), and it is especially challenging to assess the relative contribution of plasticity versus genetically based differences, when natural populations are compared.

The cichlid fishes of the Great East African lakes have become a paradigm for explosive speciation and adaptive radiation. Two key innovations are thought to be responsible for the cichlid’s success in populating the lake via adaptive radiation: their second set of jaws decoupled from the oral jaws (Liem, 1973) and their highly specialized reproductive behavior (Crapon de Caprona, 1986). These behavioral and morphological characteristics enable them to utilize a variety of specific trophic niches faster than any other fish group, so that complexly intertwined species communities have formed. Aside from geological processes, lake-level changes were argued to have significantly contributed to the diversification of cichlid fishes (Sturmbauer and Meyer, 1992; Cohen et al., 1993, 1997; Rüber et al., 1998; Baric et al., 2003; Verheyen et al., 2003; Sturmbauer et al., 2005; Duftner et al., 2007), by generating repeated cycles of population subdivision, geographic isolation and divergence, followed by secondary admixis. The effect multiplied all along the lake shore toward a gigantic scenario of allopatric speciation, termed ‘species pump’ (Rossiter, 1995). The connection between ecomorphological divergence and speciation is a central issue in adaptive radiation, and the role of competition in driving the process has long been suggested (Fryer, 1959; Coulter, 1994). Competition for trophic resources has led to habitat partitioning and the establishment and maintenance of distinct trophic morphologies in the context of adaptive radiation (Albertson, 2008) and ecological speciation (Rundle and Nosil, 2005).

The Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish genus Tropheus, with six nominal species and about 120 mostly allopatric ‘color morphs’ (Poll, 1986; Schupke, 2003), is an ideal study system to target allopatric divergence and speciation at a mature stage of adaptive radiation. Despite great evolutionary age and a large variety of color patterns within this genus, morphology and size have been reported to be highly constrained (Sturmbauer and Meyer, 1992), owing to the fact that all populations and sister species fill the same trophic niche in the littoral species community. However, recent geometric morphometric studies have identified significant mean shape differences among several Tropheus populations, which in part might be adaptive and in part may be owing to neutral drift (Maderbacher et al., 2008; Postl et al., 2008; Herler et al., 2010). The evolutionary history and the phylogeography of the genus Tropheus has been investigated in a series of molecular genetic studies (for example, Sturmbauer and Meyer, 1992; Sturmbauer et al., 1997; Baric et al., 2003; Sturmbauer et al., 2005; Egger et al., 2007; Koblmüller et al., 2008). The present distribution of genetic lineages shows a great degree of overlap, especially at the borders of the three lake basins, corroborating the important role of lake-level changes for dispersal and admixis (Sturmbauer et al., 2005). At such border regions, major lineages have come into secondary contact, and they have either hybridized or remained reproductively isolated, so that two or more species of Tropheus sometimes live in sympatry.

Tropheus lives at rock and cobble shores where it inhabits a wide range of water depths, sometimes down to 40 m, but its highest density is between the depths of 0.5 and 5 m (Kohda and Yanagisawa, 1992; Sturmbauer et al., 2008). The genus is highly specialized and occupies the trophic niche of mainly browsing on filamentous algae, whereas other genera utilize different resources in this complex littoral species community (Sturmbauer et al., 1992; Konings, 1998). In the littoral zone of freshwater lakes, several ecological factors vary strongly with water depth. Tropheus moorii prefers shallow water, presumably because of the higher algal productivity, warmer temperatures and lower mortality risk caused by pelagic predatory fish. Only very large adults tend to use slightly deeper water (>5 m).

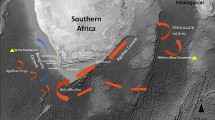

In this paper, we have studied the effects of co-occurrence of two Tropheus species in the central eastern section of Lake Tanganyika: T. moorii (color morphs ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’) and Tropheus polli. We investigated whether the sympatric Tropheus populations differ in body shape from the non-sympatric populations (that is, whether those populations that coexist with another Tropheus differ from those who do not). Thereby, we aimed to test the hypothesis that the coexistence of two ecologically (almost) equivalent species enforces competition for the available resources. Such competitive interactions might lead to spatial segregation and ecomorphological divergence. Morphological and behavioral differences among sympatric and non-sympatric Tropheus populations might in part be due to morphological plasticity and genetic variation, to be shaped by ecological or reproductive character displacement (Brown and Wilson, 1956; Pfennig et al., 2010). We studied the following natural scenario: On the eastern coast near the village Ikola, T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ lives alone and utilizes the entire range of preferred depth of 0 to about 5 m (Figure 1). Further north, T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ occurs in sympatry with T. polli. In this situation, T. polli occupies the uppermost section of the rocky habitat, whereas T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ lives in the deeper sections of the rocky littoral zone between depths of about 3–5 m (Schupke, 2003; Sturmbauer, personal observations). However, the depth separation is not complete, and the two species show some overlap in their distributions. Our study also included another color morph, T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’, which lives slightly north of T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ on the shores of the Mahale Mountains. Likewise, it shares the habitat with T. polli and shows the same depth segregation as T. moorii ‘Kaiser’. T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ is similar in color to T. moorii ‘Kaiser’, in that T. ‘Kirschfleck’ shows two red blotches on the body flanks, whereas T. ‘Kaiser’ shows a wide yellow band, and both color morphs share a relatively recent common ancestry (Egger et al., 2007). Note, however, that even populations assigned to the same color morph differ slightly from each other. Aquarium cross-breeding experiments confirmed assortative mating and reproductive isolation of T. polli from T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ (Sturmbauer, unpublished data). T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’ readily form hybrids in captivity (Toby Veall, personal communication).

Sampling localities at Lake Tanganyika. (a) Tropheus moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ in sympatry with Tropheus polli near Mahale (KFS1) and Mabilibili (KFS2); (b) T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ in sympatry with T. polli from the south of Isonga (IKS3), north of Kekese (IKS4) and at Kekese (IKS5); sympatric T. polli (TPS1–TPS5); (c) Non-sympatric T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ living alone without a second Tropheus north of Ikola (IKA1), at Ikola (IKA2) and south of Ikola (IKA3).

This study builds on a previous study in which we produced and analyzed F1 offspring of four Tropheus color morphs in a standardized pond environment and F1 hybrids between two sets of Tropheus color morphs (Kerschbaumer et al., 2011). In addition to T. moorii ‘Mbita’ and ‘Nakaku’, we bred and hybridized two populations of T. moorii ‘Kaiser’—one living alone and one in sympatry with T. polli—which are also used in the present analysis. We found that the shift to a standardized pond environment not only induced marked phenotypic plasticity but also, at the same time, left a morphological distinctness among the populations intact in that the F1 offspring of all four pond-raised Tropheus populations could be equally differentiated. Thus, despite the clear signal of phenotypic plasticity, a genetic basis for the observed morphometric differences between the populations exists. The amount of shape change due to phenotypic plasticity exceeded the differences among these populations by a factor of 2.4. We also demonstrated a heritable basis for particular morphological features differing among various Tropheus populations (Koch et al., 2012).

To address the question of whether these differences have an adaptive background, we applied geometric morphometric methods in combination with an analysis of neutral genetic markers. We further related morphological and genetic differences to the geographic distribution of the populations.

Materials and methods

Study populations and sampling

During 2005–2009, about 800 individuals of two color morphs and two species of the genus Tropheus were collected from eight locations on the eastern coast of Lake Tanganyika (Figure 1). At three locations, one T. moorii population occupied the full range of the preferred habitat (termed ‘non-sympatric Tropheus ‘Kaiser’’), and at five locations, one population shared its habitat with a sister species, T. polli (termed ‘sympatric Tropheus ‘Kaiser’’ and ‘sympatric Tropheus ‘Kirschfleck’’). T. moorii ‘Kaiser’, which is also named Tropheus ‘Ikola’ in the aquarium trade, has an overall black body with a bold yellow band across the center of the body. The basic coloration of T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ is black, with two prominent red blotches on its body flanks. Both color morphs show a cline in hue along their distribution range. T. polli is characterized by a striped pattern (females and juveniles) or uniform bluish-grey color (mature males) and a unique deeply forked caudal fin. Sample sizes, names and geographic coordinates of the sampling sites are listed in Table 1. For this study, only adult fish were considered. Digital images of anesthetized specimens were obtained using a common flatbed scanner (Herler et al., 2007). A small fin clip was taken for genetic analysis.

Morphometric analysis

External body form was quantified by digitizing the Cartesian coordinates of 18 landmarks (Figure 2) using TpsDig 2.10 (Rohlf, 2006). The landmark configurations were superimposed using a generalized Procrustes analysis (Rohlf and Slice, 1990; Mitteroecker and Gunz, 2009) and projected into Procrustes tangent space (Rohlf, 1999). The empirical distribution of population mean shapes was assessed using a principal component (PC) analysis of the resulting shape coordinates. PCs and group mean differences were visualized using thin-plate spline (TPS) deformation grids (Bookstein, 1991). Total within-population shape variance was computed as the trace of the corresponding covariance matrix of shape coordinates. Population differences in mean shape and total variance were tested for statistical significance using Monte–Carlo permutation tests (Good, 2000).

Positions of the 18 digitized landmarks: (1) Anterior tip of the snout; (2) and (3) anterior and posterior insertion of the dorsal fin; (4) and (6) upper and lower insertion of caudal fin; (5) midpoint of the origin of the caudal fin; (7) and (8) posterior and anterior insertion of the anal fin; (9) insertion of the ventral fin; (10) ventral tip of cleithrum (11); most ventral point of the border between interoperculum and sub-operculum; (12) the point where preoperculum, inter-operculum, and suboperculum get in contact; (13) upper insertion of the pelvic fin; (14) dorsal origin of the operculum; (15) dorsal end of the preopercular groove; (16) and(17) most anterior and most posterior points of the orbit; and (18) most posterior point of the lips.

According to Lande (1979), the additive genetic between-population covariance matrix is expected to be proportional to the ancestral within-population covariance matrix under pure genetic drift. Deviations from proportionality may indicate evolutionary scenarios involving disruptive or stabilizing selection (Chapuis et al., 2008). As surrogates for the genetic covariance matrices, we estimated the pooled phenotypic within-population covariance matrix and the phenotypic between-population covariance matrix of the T. moorii populations (Cheverud, 1988; Roff, 1997). We performed a likelihood ratio test of proportionality of the two covariance matrices (Mardia et al., 1979; Chapuis et al., 2008). In order to compute this test, the data were reduced to the first 10 PCs so that the covariance matrices were invertible. For our data, the results did not depend on the number of selected PCs.

This quantitative genetic approach relies on several highly idealized assumptions (see, for example, Lande, 1979; Cheverud, 1988; Roff, 1997; Marroig and Cheverud, 2004; Pigliucci, 2006) and is applied to a limited number of populations. Hence, in addition to the likelihood ratio test, we explored how much the within- and between-population covariance matrices actually differed relative to the differences between the population covariance matrices. For this purpose, we performed an ordination analysis of the eight population covariance matrices, the pooled within-population covariance matrix and the between-population covariance matrix. As a distance function, we used the two-norm of the log relative eigenvalues, the natural metric on the space of covariance matrices (Mitteroecker and Bookstein, 2009). Again, this analysis must be based on a small set of PCs so that all matrices are invertible. Analyses of the first three to seven PCs yielded roughly the same ordination; we thus report the four PC version here.

Furthermore, we assessed the pattern of differences among the within- and the between-population covariance matrices using scatter plots of the corresponding shape coordinates, together with landmark-wise equal frequency ellipses. This ‘graphical decomposition’ of variation allows for a visual inspection and localization of differences in the patterns of variance and covariance (see also Herler et al., 2010). All statistical and morphometric analyses were performed in Mathematica 8 using routines programmed by Philipp Mitteroecker and Philipp Gunz.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from ethanol-preserved fin clips via enzymatic digestion using proteinase K, followed by ammonium acetate and isopropanol precipitation (Sambrook et al., 1989). All samples were examined for genetic variation in six microsatellite markers: UNH130 (Lee and Kocher, 1996), Pzep2, Pzep3 (van Oppen et al., 1997), UME003, UME002 (Parker and Kornfield, 1996) and TmoM27 (Zardoya et al., 1996). PCR amplification was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl. PCR cocktail contained 50 ng of extracted total DNA, 0.025–0.2 μm μl−1 of primer (forward primers were fluorescently labeled with HEX, 6-FAM or NED), 0.05 nmol dNTP mix (10 mm), 0.5 μl of BSA (100 × BSA; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 30 nmol of MgCl buffer (15 mm) and 0.2 μl of Taq polymerase (5 U μl−1; BioTherm, GenXpress, Vienna, Austria). All PCR reactions were performed under the following conditions: 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles at 92 °C for 30 s; 51–54 °C, 1 min; 72 °C, 1 min, followed by 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were loaded on an Applied Biosystems 3130xl sequencer and scored by eye using the Genemapper v.3.7 software (Applied Biosystems, Vienna, Austria) against an internal ABI ROX 500 size standard. We used the software Micro-Checker (van Oosterhout et al., 2004) to assess the potential presence of null alleles. The inferred genotypic information was evaluated for deviations from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (FIS per population), and gene diversity, number of alleles and allelic richness were calculated using the software FSTAT v. 2.9.3.2 (Goudet 1995). Using the software GENEPOP 4.0 (Raymond and Rousset, 1995; Rousset, 2010) tests for linkage disequilibrium were performed using the default Markov chain parameters. Among-population differentiation was quantified using Arlequin 3.1.1 (Excoffier et al., 2006) by calculating pair-wise FST (Wright, 1951). To illustrate genetic divergence among populations, we performed a principal coordinate analysis based on the FST distance matrix. In order to visualize the relative similarity among different groups of populations, a factorial correspondence analysis was performed on microsatellite data using Genetix v. 4.05 (Belkhir et al., 2004; data not shown).

Results

Morphological differentiation

Figure 3a shows a scatter plot of the first two PCs of the 13 population means. These two components accounted for 78% of the total shape variation among the population means. The sympatric ‘Kaiser’ populations were very similar to the sympatric ‘Kirschfleck’ populations, whereas both differed from the non-sympatric Tropheus populations. The mean shapes of the five T. polli populations clearly differed from those of all T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’ populations. The shape differences corresponding to the two PCs are visualized in Figures 3b and c. Despite apparent mean differences, there was an overlap of individual variations between the populations, both in a PC analysis and in a canonical variate analysis. Only T. polli and T. moorii could be separated in a two-group discriminant analysis (not shown).

Principal component analysis of the 13 population mean shapes. (a) Scatter plot of the first two principal components (PCs), accounting for 78% of total shape variation among the population means. The shape differences corresponding to PC 1 and PC 2 are visualized in (b) and (c) as deformation grids from the grand mean shape to shapes corresponding to scores of −0.1 and 0.1 along the PCs, respectively. IKS, sympatric T. moorii ‘Kaiser’; IKA, non-sympatric T. moorii ‘Kaiser’; KFS, sympatric T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’; TPS, T. polli.

In full Procrustes shape space, the three overall mean shapes of sympatric ‘Kaiser’, non-sympatric ‘Kaiser’ and sympatric ‘Kirschfleck’ all differed significantly from each other (P<0.001 for the three tests). Figure 4 shows TPS deformation grids between these group mean shapes. The non-sympatric Tropheus populations had a relatively enlarged head and a more posteriorly positioned pectoral fin compared with the sympatric populations. The differences between non-sympatric ‘Kaiser’ and sympatric ‘Kirschfleck’ were virtually the same as those depicted in Figure 2a and thus are not shown. Shape differences between T. moorii and T. polli were detected for overall body proportions, pectoral fin position, as well as the relative size and shape of the head.

Table 2 gives the total variance of Procrustes shape coordinates for the three groups of T. moorii populations and for the T. polli populations. Pooled over the corresponding populations and over both sexes, non-sympatric ‘Kaiser’ had a larger total within-population variance than both sympatric T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ (P<0.001) and sympatric T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ (P<0.001). The within-population variance of T. polli was lower than that of all T. moorii groups (P<0.001). When computed separately for the two sexes, this pattern was more pronounced in males than in females.

The maximum likelihood test indicates that the between-population covariance matrix and the pooled within-population covariance matrix of all T. moorii specimens deviated significantly from proportionality (P<0.001). The ordination analysis in Figure 5 shows that they differed quite substantially relative to the differences among the covariance matrices of the eight populations. The between- and within-population covariance structures are visualized in Figure 6 as scatter plots of the Procrustes shape coordinates along with equal frequency ellipses for each landmark. The landmark distribution within the populations (Figure 6a) deviated from that between the populations (Figure 6b) mainly in the anterior part of the head and at the insertion of the pectoral fin. Note that these plots only show the variances of the shape coordinates along with the covariances between x and y coordinates of the same landmark but do not represent covariances between shape coordinates of different landmarks.

Principal coordinate ordination (PCO) of the eight Tropheus moorii population covariance matrices, together with the pooled within-population covariance matrix (W) and the scaled between-population covariance matrix (B). Each point in this plot represents one covariance matrix, and the distance between the points approximates the metric presented by Mitteroecker and Bookstein (2009). The matrix B was scaled to be as proportional as possible to W by a maximum likelihood scaling factor (Mardia et al., 1979).

Scatter plots representing the variation of Procrustes shape coordinates (a) within Tropheus moorii populations and (b) between T. moorii population means. Equal frequency ellipses are separately drawn for each landmark. Under a scenario of pure evolutionary drift, the patters in (a) and (b) should be proportional, so that deviations from proportionality indicate selective forces.

Genetic differentiation

In the two sympatric T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ populations and some T. polli populations, several loci showed evidence of null alleles owing to homozygote excess. One locus, UME003, showed evidence of null alleles in all but one population, so we exclude this marker from further analyses. A summary of microsatellite statistics is given in Table 3. Although genetic differentiation among non-sympatric and sympatric ‘Kaiser’ populations was significant (FST between 0.033 and 0.085), it did not exceed the differentiation within non-sympatric and sympatric populations (Table 3). The principal coordinate analysis of the FST values showed a close genetic relatedness among all six ‘Kaiser’ populations, whereas the two color morphs, ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’, were clearly distinct (Figure 6). T. polli differed from both ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’, except for one population (TPS3) that clustered with the ‘Kirschfleck’ populations.

Geographic differentiation

We correlated FST values and Procrustes shape distances among the eight T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ populations with geographic distances among the corresponding sites (Figure 7 and Table 4). FST was strongly associated with geographic distance (r=0.93, P<0.001), whereas Procrustes distance was unrelated to geographic distance (r=0.05, P=0.79) and FST (r=−0.15, P=0.44). The same pattern became evident when analyzing the six T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ populations alone (not shown).

Discussion

The relative importance of natural selection and random genetic drift for diversification and speciation has been the central interest of a wide range of empirical and theoretical studies (for example, Otte and Endler, 1989; Barton, 1996; Orr, 1998; Dieckmann and Doebeli, 1999; Schluter, 2000; Kingsolver et al., 2001; Merilä and Crnokra, 2001; Coyne and Orr, 2004; Gavrilets, 2004; Leinonen et al., 2006). In this paper, we attempted to grasp the effects of natural selection on pairs of sympatric species by comparing the degree of phenotypic and genetic variation within and among selected non-sympatric Tropheus populations with the degree of variation within sympatric populations, that is, those who live with another Tropheus. T. polli shares its habitat with various Tropheus morphs along a stretch of about 100 km of the Lake Tanganyika shoreline, feeds on the same diet and is thus likely to be a strong niche competitor (Axelrod, 1977; Poll, 1986). Our population sample included populations of two of these color morphs, T. ‘Kaiser’ and T. ‘Kirschfleck’. When alone, Tropheus populations occur in a broad depth range, with the highest density occurring within the depth range of 0.5–5 m, but when they co-occur with another Tropheus, one always occupies the uppermost and seemingly preferred depth range, whereas the second (or third) Tropheus occupies deeper water, albeit with a zone of overlap. Sympatric populations thus inhabit a different and in fact more restricted habitat than the non-sympatric populations. In our case, T. polli always remains in the shallow depth zone, whereas the second (or third) Tropheus species moves toward deeper water. The movement toward deeper water is evident from the T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ populations that live alone, because these inhabit the entire depth range of rock habitat, typical for all non-sympatric Tropheus all around the lake. The same is true for Tropheus duboisi in the northern and northeastern part of Lake Tanganyika; T. duboisi consistently lives in deeper water than the second (or third) Tropheus species (Brichard, 1978), as does one of the two sympatric Tropheus species near Namanzi and Mtosi on the southeastern shore of the lake (personal observations). The water depth is likely to enforce differential selection regimes, as the more shallow-living species has to cope with more bird predators and wave action than does the deep-living species but profits from higher algal growth, whereas the deep-living species has to deal more with pelagic predators, lower algal productivity and light transmission. One can thus argue that the observed depth segregation leads to differential adaptation.

In our analysis, we found significant differences in mean shape between non-sympatric and sympatric Tropheus populations. Moreover, the sympatric populations of both T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ clustered together in the PC analysis and only slightly overlapped in shape space with the non-sympatric populations (Figure 3). Yet, an ordination of genetic similarities (FST) showed a different picture: both non-sympatric and sympatric T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ populations closely clustered together, to the exclusion of T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ (Figure 6). This observation is congruent with a phylogeographic analysis of the genus Tropheus based on AFLP (amplified fragment length polymorphism) markers (Egger et al., 2007), in which a closer relationship between T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and ‘Kirschfleck’ was found, contrasting earlier mtDNA-based results assigning them to different mtDNA lineages (Sturmbauer and Meyer, 1992; Sturmbauer et al., 1997; 2005). Although the genetic pattern may have originated to some extent from a combination of founder effects and drift, the incongruence between neutral genetic similarities and morphological similarities is a strong indication of the action of differential selective processes in non-sympatric versus sympatric Tropheus populations. Despite the increase of genetic isolation among T. moorii ‘Kaiser’ and T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ populations with geographic distance, sympatric populations of both color morphs were morphologically alike and differed from non-sympatric populations. Sympatric populations had a relatively smaller head, smaller eyes and a more anterior insertion of the pectoral fin than did non-sympatric populations (Figure 4a). These features appear to be an adaptation to environmental features at greater water depth and reduced light transmission. For example, Jordan et al. (2008) observed a decrease of eye diameter with a decrease of light transmission in rock-dwelling cichlids from Lake Malawi. Also, Tropheus living in shallower water may need larger eyes to better detect bird predators. Differences in head size and eye size could also partly be an adaptation to (slightly) different food resources in shallow versus deeper water depth.

We further found that genetic distances (FST) between Tropheus populations were strongly associated with geographic distances, as expected, for neutral markers (Figure 8a). Morphological distances (Procrustes distances), by contrast, were unrelated to geographic distances (Figure 8b). The independence of genetic distances and morphological distances (Figure 8c) confirms the incongruence between the two ordination analyses in Figures 3 and 6.

Scatter plots of (a) geographic distances versus FST values, (b) geographic distances versus Procrustes distances and (c) FST values versus Procrustes distances between the eight Tropheus moorii populations. FST is strongly associated with geographic distance (r=0.93), whereas Procrustes distance is unrelated to both geographic distance and FST (r=0.05 and r=−0.15, respectively).

T. polli differed both genetically and morphologically from the other species. However, one population (TPS3) shared some alleles with T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ and hence differed from the other T. polli populations in the ordination in Figure 6. The observed similarity to its sympatric ally is indicative of a past introgression event at this location. In fact, the presence of mtDNA haplotypes from two major lineages in T. moorii ‘Kirschfleck’ suggest a short period of gene flow, possibly in the form of a reinforcement scenario upon initial secondary contact (Sturmbauer et al., 1997).

Additional evidence of selective processes comes from the comparison between within-population and between-population covariance matrices for the studied T. moorii populations. We found that the two phenotypic covariance matrices clearly deviated from proportionality, indicating evolutionary scenarios involving disruptive or stabilizing selection. Variation between populations (Figure 5b) differed from that of within populations (Figure 5a), most clearly in the landmarks of the head, particularly of the mouth, and of the anterior insertion of the pectoral fin. In these anatomical regions, non-sympatric and sympatric populations differed the most (Figure 4a).

We also found that the total within-population variance (summed over all landmarks) was significantly smaller in the sympatric populations than in the non-sympatric populations. This can be a result of increased stabilizing selection pressure owing to food competition of T. moorii with T. polli and other fishes in the deeper water. Recent work on Lake Malawi rock-dwelling cichlids on community structure and phenotypic divergence have suggested that sedimentation seems to be another factor affecting foraging behavior structuring species and eco-types along this habitat gradient (Albertson, 2008; Parnell and Streelman, 2011), so niche segregation might as well happen among the two Tropheus.

Two previous studies, in which offspring of sympatric and non-sympatric Tropheus ‘Kaiser’ were bred in a standardized pond environment and compared with wild fish, revealed striking phenotypic plasticity induced by the sudden shift of several environmental parameters in the ponds. Lack of competitors and predators and completely calm water might be the most striking changes. However, the same experiment demonstrated a clear genetic basis of some of the observed inter-population differences in the F1 offspring (Kerschbaumer et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2012). One might argue that non-sympatric and sympatric populations live in slightly different habitats, so the observed mean shape differences could in part be due to the different environments shaping ontogenetic development. Likewise, the reduced shape variation in sympatric populations might result from their decreased habitat heterogeneity, given that each species inhabits one part of the original depth range. As argued by West-Eberhard (2005a), 2005b, such environmentally induced phenotypic differences, within the impressive scope of phenotypic plasticity, are likely to be the initial basis on which natural selection can act. The observed genetic basis of population differences demonstrates a contribution of random mutations, providing the basis for genetic accommodation. Thus, phenotypic plasticity can promote divergence within populations, divergence via resource partitioning and character displacement upon secondary contact between species, to ultimately drive speciation and adaptive radiation (Pfennig et al., 2010). Such scenarios were postulated for the repeated formation of benthic and limnetic sticklebacks (Schluter and McPhail, 1992). It was also argued that developmental plasticity mirrors the morphological differences found in three genera of spadefoot toads across two continents, as an indication of how ancestral plasticity may lead to morphological diversity driven by adaptation to broad environmental changes (Gomez-Mestre and Buchholz, 2006).

It is thus evident that natural selection acts on both the scope of phenotypic plasticity and heritable traits and that both factors contribute to the observed shape differences among non-sympatric and sympatric Tropheus populations. Phenotypic plasticity is a highly important adaptive feature allowing individuals to react to more short-term environmental changes. Once natural selection begins to act consistently in one direction, for example, on account of behavioral changes after secondary admixis, genetically based changes are likely to emerge on top of plasticity, and this is exactly what our data suggest. We note that our study design does not allow us to disentangle the relative contributions of phenotypic plasticity and genetically based differences. The relative contributions of plasticity and genetically based differences can be disentangled by experimental studies where sympatric and non-sympatric populations are raised under various environmental conditions and, additionally, in a common garden design.

It seems highly likely that the body shape differences between non-sympatric and sympatric T. moorii populations are caused by ecological character displacement. Experimental data showing the fitness effects of competition and measures of selection on the traits of interest would be useful in making a stronger case. One alternative, reproductive character displacement, that is, the increase of isolation between taxa that are already good species (as opposed to reinforcement), seems less likely, given that all distinctive traits have a plausible ecological background. According to the six check-criteria for character displacement suggested by Grant (1972) and Arthur (1982) and considering the remarks of Schluter and McPhail (1992), the following evaluation can be made:

-

1

Chance can be ruled out as an explanation of the pattern, given that other cases of sympatry also constitute the same depth segregation of the two entities.

-

2

According to pond-breeding experiments (Kerschbaumer et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2012), the phenotypic differences among populations in sympatry and allopatry have a genetic basis, on top of plasticity.

-

3

That enhanced differences between sympatric species are the outcome of evolutionary shifts, not simply of the inability of similarly sized species to coexist (for example, because of competitive exclusion or introgression), seems likely owing to the adaptive background of the changes, but must be investigated further by fitness-related studies on traits under divergent selection.

-

4

As sympatric populations of T. moorii consistently occupy the deeper section of the original depth range, and as they share changes in eye diameter, head proportions and the insertion of the pectoral fin, it is likely that these morphological (or other phenotypic) differences reflect differences in resource use. Further experimental studies will provide more evidence.

-

5

The sites of sympatry and allopatry do not differ greatly in habitat properties and thus food, climate or other environmental features affecting the phenotype are likely to be the same. The sites at which T. moorii populations live alone are situated at the southern end of the distribution area of this Tropheus morph in the same type of moderately sloping cobble shore, so it is likely that T. polli just never successfully colonized this southernmost section. This point also includes Grant’s (1975) criterion that differences in the zone of sympatry should not be predictable from geographic variation outside the zone, which clearly is not the case, as it is the same color morph of T. moorii.

-

6

The sixth criterion requires that independent evidence that similar phenotypes actually compete for food should be gained. This evidence can be derived from the fact that the >100 allopatric Tropheus populations fill the same function (trophic niche) in the complex and species-rich littoral species community. However, diet data or stable isotope data are not available so far.

Taken together, we found two independent lines of evidence for adaptive processes underlying body shape differences in closely related non-sympatric and sympatric Tropheus populations. Despite considerable genetic separation between these populations, all sympatric populations occupying deeper water have a relatively smaller head, smaller eyes and a more anterior insertion of the pectoral fin than do non-sympatric populations. Secondary contact of T. polli with T. moorii, which have evolved reproductive isolation, seems to have enforced a niche shift in both involved taxa, that in turn has led to disruptive selection among genetically closely related populations and to convergent selection among more distantly related populations. The observed concordance in shape in five sympatric populations of T. moorii, in contrast to the non-sympatric populations, together with the shift in resource use, is strong evidence of ecological character displacement (Grant, 1972; Wassermann and Koepfer, 1977; Simberloff and Boecklen, 1981; Schluter, 1986), albeit we are aware that this is not conclusive. Our findings are concordant with other cases of early species divergence, such as those of Schluter and McPhail (1992), as well as those of Adams and Rohlf (2000) on two small and closely related salamanders (see the review of Losos, 2000), Darwin’s finches (Grant and Grant, 2006) and nightingales (Reifová et al. 2011).

Data archiving

Data deposited in the Dryad repository: doi:10.5061/dryad.fc02f.

References

Adams DC, Rohlf FJ . (2000). Ecological character displacement in Plethodon: Biomechanical differences found from a geometric morphometric study. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 97: 4106–4111.

Axelrod GC . (1977). A new species of Tropheus (Pisces: Cichlidae) from Lake Tanganyika. J. L. B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology, Rhodes University, South Africa, Special Publication No. 17 1–2.

Albertson RC . (2008). Morphological divergence predicts habitat partitioning in a Lake Malawi cichlid species complex. Copeia 2008: 690–699.

Arthur WA . (1982). The evolutionary consequences of interspecific competition. Adv Ecol Res 12: 127–187.

Barton NH . (1996). Natural selection and random genetic drift as causes of evolution on islands. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 351: 785–795.

Baric S, Salzburger W, Sturmbauer C . (2003). Phylogeography and evolution of the Tanganyikan cichlid genus Tropheus based upon mitochondrial DNA sequences. J Mol Evol 56: 54–68.

Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F . (2004) GENETIX 4.05, Logiciel sous Windows TM pour la Génétique des Populations. Université de Montpellier II: Montpellier, France.

Bookstein FL . (1991) Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA.

Brichard P . (1978) Fishes of Lake Tanganyika. T.F.H Publications: Neptune City, NJ, USA.

Brown WL, Wilson EO . (1956). Character displacement. Syst Zool 5: 49–64.

Chapuis E, Martin G, Goudet J . (2008). Effects of selection and drift on G matrix evolution in a heterogeneous environment: a multivariate Qst–Fst test with the freshwater snail Galba truncatula. Genetics 180: 2151–2161.

Cheverud JM . (1988). A comparison of genetic and phenotypic correlations. Evolution 42: 958–968.

Cohen AS, Soreghan MJ, Scholz CA . (1993). Estimating the age of formation of lakes: an example from Lake Tanganyika, East-African rift system. Geology 21: 511–514.

Cohen AS, Lezzar KE, Tiercelin JJ, Soreghan M . (1997). New palaeogeographic and lake level reconstructions of Lake Tanganyika: implications for tectonic, climatic and biological evolution in a rift lake. Basin Res 9: 107–132.

Coulter GW . (1994). Speciation and fluctuating environments, with reference to ancient East African lakes. In: Martens K, Goodeeris B, Coulter GW (eds).. Advances in limnology vol. 44 Speciation in Ancient Lakes. Schweizerbart́sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 127–337.

Coyne JA, Orr HA . (2004) Speciation. Sinauer Associates Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA.

Crapon de Caprona MD . (1986). Are ‘preferences’ and ‘tolerances’ in cichlid mate choice important for speciation? J Fish Biol 29: 151–158.

DeWitt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS . (1998). Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol 13: 77–81.

Dieckmann U, Doebeli M . (1999). On the origin of species by sympatric speciation. Nature 400: 354–357.

Duftner N, Sefc KM, Koblmüller S, Salzburger W, Taborsky M, Sturmbauer C . (2007). Parallel evolution of facial stripe patterns in the Neolamprologus brichardi/pulcher species complex endemic to Lake Tanganyika. Mol Phylogenet Eol 45: 706–715.

Egger B, Koblmüller S, Sturmbauer C, Sefc KM . (2007). Nuclear and mitochondrial data reveal different evolutionary processes in the Lake Tanganyika cichlid genus Tropheus. BMC Evol Biol 7: 137.

Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S . (2006) Arlequin ver. 3.11: An Integrated Software Package for Population Genetics Data Analysis. Computational and Molecular Population Genetics Lab (CMPG), Institute of Zoology, University of Berne: Berne, Switzerland.

Fryer G . (1959). Some aspects of evolution in Lake Nyasa. Evolution 13: 440–451.

Gavrilets S . (2004) Fitness Landscapes and the Origin of Species. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA.

Gomez-Mestre I, Buchholz DR . (2006). Developmental plasticity mirrors differences among taxa in spadefoot toads linking plasticity and diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 19021–19026.

Good P . (2000) Permutation Tests: A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses. Springer: New York, NY, USA.

Goudet J . (1995). FSTAT (Version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Heredity 86: 385–486.

Grant PR . (1972). Convergent and divergent character displacement. J Linn Soc 4: 39–68.

Grant PR . (1975). The classical case of character displacement. Evol Biol 5: 237–337.

Grant PR, Grant BR . (2006). Evolution of character displacement in Darwin’s Finches. Science 313: 224–226.

Herler J, Lipej L, Makovec T . (2007). A simple technique for digital imaging of live and preserved small fish specimens. Cybium 31: 39–44.

Herler J, Kerschbaumer M, Mitteroecker P, Postl L, Sturmbauer C . (2010). Sexual dimorphism and population divergence in the Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish genus Tropheus. Front Zool 7: 4.

Jordan R, Howe D, Kellogg K, Juanes F, Stauffer J, Garcia-Vazquez E . (2008). Small-scale morphological differentiation in a cichlid may provide clues about rapidly diversifying systems. African J Ecol 46: 107–109.

Kerschbaumer M, Postl L, Koch M, Wiedl T, Sturmbauer C . (2011). Morphological distinctness despite large-scale phenotypic plasticity—analysis of wild and pond-bred juveniles of allopatric populations of Tropheus moorii. Naturwissenschaften 98: 125–134.

Kingsolver JG, Hoekstra HE, Hoekstra JM, Berrigan D, Vignieri SN, Hill CE et al. (2001). The strength of phenotypic selection in natural populations. Am Nat 157: 245–261.

Koblmüller S, Sefc KM, Sturmbauer C . (2008). The Lake Tanganyika cichlid species assemblage: recent advances in molecular phylogenetics. Hydrobiologia 615: 5–20.

Koch M, Wilson AJ, Kerschbaumer M, Wiedl T, Sturmbauer C . (2012). Additive genetic variance of quantitative traits in natural and pond-bred populations of the Lake Tanganyika cichlid Tropheus moorii. Hydrobiologia 682: 131–141.

Kohda M, Yanagisawa Y . (1992). Vertical distributions of two herbivorous cichlid fishes of the genus Tropheus in Lake Tanganyika, Africa. Ecol Freshw Fish 1: 99–103.

Konings A . (1998) Tanganyika Cichlids in Their Natural Habitat. Cichlid Press: El Paso, TX, USA.

Lande R . (1979). Quantitative genetic analysis of multivariate evolution, applied to brain: body size allometry. Evolution 33: 402–416.

Lee WJ, Kocher TD . (1996). Microsatellite DNA markers for genetic mapping in Oreochromisniloticus. J Fish Biol 49: 169–171.

Leinonen T, Cano JM, Makinen H, Merilä J . (2006). Contrasting patterns of body shape and neutral genetic divergence in marine and lake populations of threespine sticklebacks. J Evol Biol 19: 1803–1812.

Liem KF . (1973). Evolutionary strategies and morphological innovations: cichlid pharyngeal jaws. Syst Zool 22: 425–441.

Losos JB . (2000). Ecological character displacement and the study of adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5693–5695.

Maderbacher M, Bauer C, Herler J, Postl L, Makasa L, Sturmbauer C . (2008). Assessment of traditional versus geometric morphometrics for discriminating populations of the Tropheus moorii species complex (Teleostei: Cichlidae), a Lake Tanganyika model for allopatric speciation. J Zool Syst Evol Res 46: 153–161.

Marcil J, Swain DP, Hutchings JA . (2006). Countergradient variation in body shape between two populations of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Proc Roy Soc B 273: 217–223.

Mardia KV, Kent JT, Bibby JM . (1979) Multivariate Analysis. Academic Press: London, UK.

Marroig G, Cheverud JM . (2004). Did natural selection or genetic drift produce the cranial diversification of neotropical monkeys? Am Nat 163: 417–428.

Merilä J, Crnokra P . (2001). Comparison of genetic differentiation at marker loci and quantitative traits. J Evol Biol 14: 892–903.

Mitteroecker P, Bookstein FL . (2009). The ontogenetic trajectory of the phenotypic covariance matrix, with examples from craniofacial shape in rats and humans. Evolution 63: 727–737.

Mitteroecker P, Gunz P . (2009). Advances in geometric morphometrics. Evol Biol 36: 235–247.

Orr HA . (1998). Testing natural selection vs. genetic drift in phenotypic evolution using quantitative trait locus data. Genetics 149: 2099–2104.

Otte D, Endler JA . (1989) Speciation and its Consequences. Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA.

Parker A, Kornfield I . (1996). Polygyandry in Pseudotropheus zebra, a cichlid fish from Lake Malawi. Environ Biol Fish 47: 345–352.

Parnell NF, Streelman JT . (2011). The macroecology of rapid evolutionary radiation. Proc Roy Soc B 278: 2486–2494.

Pfennig DW, Wund MA, Snell-Rood EC, Cruickshank T, Schlichting CD, Moczek AP . (2010). Phenotypic plasticity’s impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 25: 459–467.

Pigliucci M . (2006). Genetic variance-covariance matrices: a critique of the evolutionary quantitative genetics research program. Biol Philos 21: 1–23.

Poll M . (1986). Classification des cichlidae du lac Tanganika. Tribus, genres et espèces. Acad R Belg Mem Cl Sci 45: 1–163.

Postl L, Herler J, Bauer C, Maderbacher M, Makasa L, Sturmbauer C . (2008). Geometric morphometrics applied to viscerocranialbones in three populations of the Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish Tropheus moorii. J Zool Syst Evol Res 46: 240–248.

Raymond M, Rousset F . (1995). GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Heredity 86: 248–249.

Reifová R, Reif J, Antczak M, Nachmann MW . (2011). Ecological character displacement in the face of gene flow: evidence from two species of nightingales. BMC Evol Biol 11: 138.

Roff DA . (1997) Evolutionary Quantitative Genetics. Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA.

Rohlf FJ . (1999). Shape statistics: Procrustes superimpositions and tangent spaces. J Classif 16: 197–223.

Rohlf FJ . (2006) TpsDig 2.10. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY, USA.

Rohlf FJ, Slice D . (1990). Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool 39: 40–59.

Rossiter A . (1995). The cichlid fish assemblages of Lake Tanganyika: ecology, behaviour and evolution of its species flocks. Adv Ecol Res 26: 187–252.

Rousset F . (2010). Genepop'007: a complete reimplementation of the Genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Res 8: 103–106.

Rüber L, Verheyen E, Sturmbauer C, Meyer A . (1998). Lake level fluctuations and speciation in rock-dwelling cichlid fish in Lake Tanganyika, East Africa. In: Grant P ed. Evolution on Islands.. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK. pp 225–240.

Rundle HD, Nosil P . (2005). Ecological speciation. Ecol Lett 8: 336–352.

Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T . (1989) Molecular cloning: A Laboratory Manual 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbour: New York, NY, USA.

Schluter D . (1986). Character displacement between distantly related taxa—finches and bees in the Galapagos. Am Nat 127: 95–102.

Schluter D . (2000) The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

Schluter D, McPhail JD . (1992). Ecological character displacement and speciation in sticklebacks. Am Nat 140: 85–102.

Schupke P . (2003) Cichlids of Lake Tanganyika, Part 1: The Species of the Genus Tropheus. Aqualog, ACS GmbH, Rodgau: Germany.

Simberloff DS, Boecklen W . (1981). Santa rosalia reconsidered: size ratios and competition. Evolution 35: 1206–1228.

Sturmbauer C, Mark W, Dallinger R . (1992). Ecophysiology of Aufwuchs-eating cichlids in Lake Tanganyika: niche separation by trophic specialization. Environ Biol Fish 35: 283–290.

Sturmbauer C, Meyer A . (1992). Genetic divergence, speciation and morphological stasis in a lineage of African cichlid fishes. Nature 358: 578–581.

Sturmbauer C, Verheyen E, Rüber L, Meyer A . (1997). Phylogeographic patterns in populations of cichlid fishes from rocky habitats in Lake Tanganyika. In: Stepien CA, Kocher TD (eds). Molecular Systematics of Fishes. Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA. pp 97–111.

Sturmbauer C, Koblmüller S, Sefc KM, Duftner N . (2005). Phylogeographic history of the genus Tropheus, a lineage of rock-dwelling cichlid fishes endemic to Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia 542: 335–366.

Sturmbauer C, Fuchs C, Harb G, Damm E, Duftner N, Maderbacher M et al. (2008). Abundance, distribution and territory areas of rock-dwelling Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish species. Hydrobiologia 615: 57–68.

Suzuki Y, Nijhout HF . (2006). Evolution of a polymorphism by genetic accommodation. Science 311: 650–652.

Van Oppen MHJ, Turner GF, Rico C, Deutsch JC, Ibrahim KM, Robinson RL et al. (1997). Unusually fine-scale genetic structuring found in rapidly speciating Malawi cichlid fishes. Proc Roy Soc Lond B 264: 1803–1812.

Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P . (2004). MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes 4: 535–538.

Verheyen E, Salzburger W, Snoeks J, Meyer A . (2003). Origin of the cichlid fishes from Lake Victoria, East Africa. Science 300: 325–329.

Via S, Lande R . (1985). Genotype-environment interaction and the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Evolution 39: 505–522.

Wasserman M, Koepfer HR . (1977). Character displacement for sexual isolation between Drosophila mojavensis and Drosophila arizonensis. Evolution 31: 812–823.

West-Eberhard M-J . (2005a). Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 102: 6543–6549.

West-Eberhard M-J . (2005b). Phenotypic accommodation: adaptive innovation due to developmental plasticity. J Exp Zool (Mol Dev Evol) 304: 610–618.

Wright S . (1951). The genetical structure of populations. Ann Eugenics 15: 323–354.

Zardoya R, Vollmer DM, Craddock C, Streelman JT, Karl S, Meyer A . (1996). Evolutionary conservation of microsatellite flanking regions and their utility in resolving the phylogeny of cichlid fishes (Pisces: Perciformes). Proc Roy Soc Lond B 263: 1611–1618.

Acknowledgements

We thank Helen Gunter, Stephan Koblmüller and Steven Weiss, as well as four anonymous reviewers, for insightful comments on the manuscript. This study was financed by the Projects P20994-B03 and I48-B0 of the Austrian Science Fund and the Projects 2007-04 and 2010-04 of the Commission of interdisciplinary Ecological Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences to CS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kerschbaumer, M., Mitteroecker, P. & Sturmbauer, C. Evolution of body shape in sympatric versus non-sympatric Tropheus populations of Lake Tanganyika. Heredity 112, 89–98 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2013.78

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2013.78

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microevolutionary change in viscerocranial bones under congeneric sympatry in the Lake Tanganyikan cichlid genus Tropheus

Hydrobiologia (2021)

-

Delineating species along shifting shorelines: Tropheus (Teleostei, Cichlidae) from the southern subbasin of Lake Tanganyika

Frontiers in Zoology (2018)

-

Diversification of functional morphology in herbivorous cichlids (Perciformes: Cichlidae) of the tribe Tropheini in Lake Tanganyika

Hydrobiologia (2017)

-

Fishery composition and evidence of population structure and hybridization in the Atlantic bonefish species complex (Albula spp.)

Marine Biology (2016)

-

Diet disparity among sympatric herbivorous cichlids in the same ecomorphs in Lake Tanganyika: amplicon pyrosequences on algal farms and stomach contents

BMC Biology (2014)