Abstract

Gene duplications can have a major role in adaptation, and gene families underlying chemosensation are particularly interesting due to their essential role in chemical recognition of mates, predators and food resources. Social insects add yet another dimension to the study of chemosensory genomics, as the key components of their social life rely on chemical communication. Still, chemosensory gene families are little studied in social insects. Here we annotated chemosensory protein (CSP) genes from seven ant genomes and studied their evolution. The number of functional CSP genes ranges from 11 to 21 depending on species, and the estimated rates of gene birth and death indicate high turnover of genes. Ant CSP genes include seven conservative orthologous groups present in all the ants, and a group of genes that has expanded independently in different ant lineages. Interestingly, the expanded group of genes has a differing mode of evolution from the orthologous groups. The expanded group shows rapid evolution as indicated by a high dN/dS (nonsynonymous to synonymous changes) ratio, several sites under positive selection and many pseudogenes, whereas the genes in the seven orthologous groups evolve slowly under purifying selection and include only one pseudogene. These results show that adaptive changes have played a role in ant CSP evolution. The expanded group of ant-specific genes is phylogenetically close to a conservative orthologous group CSP7, which includes genes known to be involved in ant nestmate recognition, raising an interesting possibility that the expanded CSPs function in ant chemical communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The important role of gene duplications in organismal evolution has been acknowledged for a long time, and rapidly accumulating genomic data now allow estimating the dynamics of gene family evolution. Gene families expand through gene duplication and contract through gene loss or pseudogenization. The process results both in orthologous genes that have evolved from a common ancestral gene by speciation and in paralogous genes, which have been produced by gene duplication events. The number of gene copies within a gene family can vary extensively between species and even within a species (Schrider and Hahn, 2010). This copy number variation has been suggested to have a significant role in adaptation and could provide raw material for genes with new functions (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009; Innan and Kondrashov, 2010). Rapid turnover of genes within a gene family has been shown to correlate with fast evolution at sequence level (Chen et al., 2010), and gene families which are conserved in size also evolve, on average, more slowly at sequence level.

Some functional classes of genes repeatedly show signs of accelerated gene gain and loss in several animal groups. Among these are genes involved in immune defense, stress response, metabolism, cell signaling, reproduction and chemoreception (Demuth and Hahn, 2009). Genes underlying chemosensation have been studied in several insects (Nozawa and Nei, 2007; Vieira et al., 2007; Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009; Smadja et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010; Vieira and Rozas, 2011). Within chemosensory gene families, relatively few genes can be recognized as orthologues shared by different insect orders, and the number of orthologous groups quickly decreases with increasing divergence time (Vieira and Rozas, 2011). Instead, subfamilies have commonly expanded within specific taxonomic lineages presumably as a response to changing environment. Chemosensory genes are interesting also because of their putative role in speciation. Chemosensory systems and chemical signals seem to have an important role in premating isolating barriers, and recent direct evidence from pea aphids suggests that chemoreceptor genes have a role in host plant specialization and speciation (Smadja et al., 2012).

Social insects (ants, termites, social bees and wasps) add yet another dimension to the study of chemosensory genomics because their communication takes place in a highly complex social context and much of their communication relies on chemicals. In addition to signals used by other animals, such as those involved in mate choice and habitat choice, social insects need to communicate to a large group of individuals in order to coordinate the actions of the whole colony. Chemical signals are for example used in ant nestmate recognition (Lahav et al, 1999), which is crucial for the colony cohesion and inclusive fitness benefits, directing the altruistic behavior to colony mates. Furthermore, chemical signals (pheromones) are used to control and suppress reproduction by other queens or workers and to stimulate specific worker tasks, for example to make them take care of larvae (Holman et al., 2010). Thus, social life involves unique long-lasting selection pressures. For example, protecting the nest against intruders drives selection for nestmate recognition; in addition, there exist extensive within colony conflicts linked to reproduction and roles of different castes. The effects of these two selection pressures could mirror that of sexual antagonism (Swanson and Vacquier, 2002) or arms race against pathogens as seen in immune genes (Sackton et al., 2007).

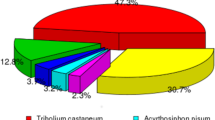

Proteins coded by several different gene families contribute to the reception of chemical messages. Growing evidence supports that odorant binding proteins (OBP) and chemosensory proteins (CSP) are involved in solubilizing and transporting odorants and pheromones through aqueous hemolymph in insects (Leal et al., 2005; Ozaki et al., 2005). The chemical messages carried by the OBPs and CSPs are decoded when odorant receptors (OR) or in some cases gustatory receptors (GR) selectively bind different chemicals (Vosshall and Stocker, 2007). The odorant receptor family varies in size from 54 genes in Drosophila virilis to 299 in the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Nozawa and Nei, 2007; Engsontia et al., 2008). The OBP and CSP gene families are smaller, OBP family containing 4–81 genes and CSP 3–22 genes in the insect species studied this far (Forêt and Maleszka, 2006; Forêt et al., 2007; Gong et al., 2007; Vieira and Rozas, 2011). OBPs and CSPs belong to different gene families, but possibly have common evolutionary origin of 380–450 million years ago (Mya) (Vieira and Rozas, 2011). Several studies find that chemosensory gene families evolve under purifying selection and there is no or little indication of positive selection (Forêt et al., 2007; Vieira et al., 2007; Gardiner et al., 2008; Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010). Exceptions are the pea aphid OR and GR gene families, where the most recent expansions evolve under positive selection (Smadja et al., 2009) with ecologically based selection for host plant specialization as the possible driving force. Another case is provided by the honeybee where positive selection is driving the diversification of C-subclade of the OBP gene family (Forêt and Maleszka, 2006).

In this study we focus on the CSP gene family in ants. In the ant Camponotus japonicus, one of the CSPs is the major protein expressed in the antennae and this protein binds the cuticular hydrocarbons used in nestmate recognition (Ozaki et al., 2005). Changes in this protein could thus putatively alter workers’ acceptance of individuals and discrimination between friends and foes. The major protein expressed in the antennae of the red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta is also a CSP that binds cuticular substances but not hydrocarbons (González et al., 2009). This does not rule out its possible role in nestmate recognition if recognition in the fire ants is based on other substances than hydrocarbons (González et al., 2009). The Argentine ant, Linepithema humile was also shown to express CSP as a major protein in its antennae (Ishida et al., 2002). In addition to these examples, the specific function of individual CSP genes is not well known in ants. Expression studies in the honeybee suggest that CSPs represent a multifunctional gene family and participate in a range of cellular processes, one of which is chemosensation (Forêt et al., 2007). Also, involvement in developmental processes has been shown in honeybee (Maleszka et al., 2007).

Here we identify and annotate the CSP genes from seven ant species covering a period of 130 My, and study their evolution both at gene family and sequence level by estimating the rate of gene turnover and the rate of sequence evolution (nonsynonymous to synonymous changes (dN/dS)). Our results reveal repeated expansions and a rapid rate of sequence evolution in the ant CSP genes. Surprisingly, but perhaps intuitively, we find that the ant CSP gene family comprises of two classes of genes with differing modes of evolution. Recently duplicated ant-specific genes represent one class, and show rapid evolution accompanied with positive selection and propensity to duplicate. The other class contains genes that can be found as orthologues from all the ants and partly from the honeybee, and they are evolving more slowly, with strong purifying selection and no propensity to duplicate. Our results underline that gene families are not necessarily homogenous, but can contain genes with differing modes of evolution, possibly indicating connection to their function. The ant-specific expansions and rapid evolution connected to positive selection suggest the adaptive evolution of CSP genes in ants.

Materials and methods

CSP gene identification

We annotated CSP genes in seven published ant genomes (C. floridanus, Harpegnathos saltator, S. invicta, L. humile, Pogonomyrmex barbatus, Acromyrmex echinatior and Atta cephalotes) (Bonasio et al., 2010; Nygaard et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011, 2011; Suen et al., 2011; Wurm et al., 2011) (Figure 1). The abbreviations used here are, respectively, Cflo, Hsal, Sinv, Lhum, Pbar, Aech and Acep. We first searched the predicted protein models of each ant species using the protein sequences of insect CSPs (Forêt et al., 2007; Gong et al., 2007; González et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009; Vieira and Rozas, 2011) and e-value of 1.0 e-3. Adding the hits of the first search to queries, we searched the ant genome assemblies using tblastn. We also ran HMM search recovering only one or two new hits. We ran iterative blasts until no new genes were found. All the hits were confirmed by conserved domain search in GenBank (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2011), and only sequences which belonged to the OS-D superfamily (pfam03392) were considered putative CSPs. In one case, no similarity to any protein superfamily was observed but the sequence was allocated to CSP family based on the best hits in GenBank. Pseudogenes were defined on the basis of interrupting stop codons and/or frameshifts.

Ant species used in this study. The divergence estimates are in My and based on large-scale sequence data from Brady et al. (2006) and Moreau et al. (2006).

Sequence alignment and analysis

All the retrieved sequences were aligned using several approaches (programs Muscle (Edgar, 2004), MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2005) and PRANK (Löytynoja and Goldman, 2005)). In order to evaluate whether different approaches give similar results, we made a neighbour-joining tree of each alignment and confirmed that different alignment methods produced similar overall topology. For the final analysis, we used PRANK’s codon-based alignment method as this has been shown to perform best in several comparisons (Jordan and Goldman, 2012; Privman et al., 2012). PRANK avoids overaligning sequences by paying special attention to small insertions and deletions. Our strategy was as follows. As suggested by the developer of PRANK (Löytynoja A, personal communication), we first produced an alignment with MAFFT using ant CSPs from all the seven species. This alignment was used to produce a guide tree with a maximum likelihood program RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006; Stamatakis et al., 2008). RAxML was run under default parameter values and with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree was then used as a guide tree for PRANK’s codon-based alignment. The reliability of the alignment produced by PRANK was evaluated with GUIDANCE (Penn et al., 2010), which assigns confidence scores (ranging from zero to one, one being confident) for the whole alignment and for each site separately using a bootstrap procedure. This alignment was used in subsequent molecular evolutionary analyses by using all the sequences or dividing them in subsets as indicated below. Another alignment was made with PRANK from amino acid sequences including all the ant CSP sequences (intact and pseudogenes) together with Apis mellifera and D. melanogaster sequences, and a phylogenetic tree was produced using RAxML (Figure 2). In pseudogenes, frameshifts and stop codons were marked as missing information. Also in this case, a guide tree for PRANK was first produced with MAFFT and RAxML. To compare the CSP gene evolution across different holometabolous insects, CSP sequences of T. castaneum, A. mellifera, Bombyx mori and Anopheles gambiae were retrieved from GenBank. Nucleotide sequences of each species were aligned with PRANK’s codon-based method. The MEGA 5.05 (Tamura et al., 2011) software was used to estimate amino acid divergences under the JTT empirical amino acid substitution model and applying the pairwise deletion option.

(a) Maximum likelihood tree constructed from all the ant (Cflo, Sinv, Aech, Acep, Lhum, Pbar, Hsal), honeybee (Amel) and common fruit fly (Dmel) CSP protein sequences. Gene tree shows the orthologous groups (ant CSP1–7). The ant-specific expansion has been collapsed and shown as black triangle. Confidence values above 40% (1000 bootstraps) are indicated. Genes have been named using numbers, pseudogenes are indicated with additional P in the end. (b) Only the ant-specific expansion is shown. Confidence values above 40% (1000 bootstraps) are indicated. Genes have been named using numbers, pseudogenes are indicated with additional P in the end.

To study the extent of selection affecting the CSP gene family in ants, we used the softwares HyPhy and PAML (Kosakovsky Pond and Frost, 2005a; Yang, 2007) to estimate synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions. HyPhy has several models (SLAC, FEL and REL) to study site-specific selection categorizing each site into one of the following classes: purifying selection (dN/dS <1), positive selection (dN/dS >1) or neutral evolution (dN/dS =1). We used SLAC (counting-based method) and FEL (estimates dN/dS ratio on a site-by-site basis using maximum likelihood), both of which are more conservative than REL (Kosakovsky Pond and Frost, 2005b). In PAML, we used the program codeml for branch tests and site tests (Bielawski and Yang, 2005). We first used the branch tests to compare a model of single dN/dS ratio against the free ratios model for the data containing CSP sequences from all the seven ant species. In this step, a global dN/dS was estimated from the data (model M0) and compared with a model where each branch can have its own dN/dS ratio (free ratios) with a likelihood ratio test. We also calculated the average dN/dS ratio for each ant species separately with both SLAC and codeml. To compare the dN/dS ratio in ant CSP genes with that of other insects, we calculated the dN/dS ratios of T. castaneum, A. mellifera, B. mori and A. gambiae CSP genes with SLAC in HyPhy and codeml (M0). All the phylogenetic trees used in codeml analysis were made with RAxML under default parameters and 1000 bootstraps.

The phylogenetic gene tree (Figures 2a and b) containing all the ant CSP genes shows seven well-supported orthologous groups of genes in ants (see Results for details). Most of these are old genes also found in the honeybee A. mellifera and Drosophila. In addition to orthologous genes, there are several ant-specific expansions. To test whether the orthologous groups of genes exhibit different selective regimes than the ant-specific expansions, we divided the sequences into two sets (one set is formed by functional genes in Figure 2a and other by genes in Figure 2b), and analyzed them separately. We used first HyPhy to divide sites into categories with different selective regimes (SLAC and FEL). We then used the site test in PAML comparing neutral model (M1a) with a model allowing positive selection (M2a). As some branches in the CSP gene tree have low bootstrap support, we ran PAML analyses also by collapsing the branches under 40% bootstrap support. This did not change the results. To map the positively selected sites to the protein model, we performed a search in the Protein Data Bank and found that ant CSPs are sufficiently similar to known CSP structure of Mamestra brassicae (Campanacci et al., 2003). We used Phyre2 server (Kelley and Sternberg, 2009) to model the structure of ant CSPs using HsalCSP11 as query. The resulting model was viewed in Pymol (the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5 Schrödinger, LLC, www.pymol.org) and positively selected sites were mapped to the model.

Gene gain and loss in CSP family

We estimated the rate of gene duplication and loss within the CSP gene family with the software BadiRate (Librado et al., 2011) using the seven ant species and 12 other arthropods analyzed earlier by Vieira and Rozas (2011), namely D. melanogaster, D. virilis, D. erecta, D. ananassae, A. gambiae, B. mori, T. castaneum, A. mellifera, P. humanus, A. pisum, D. pulex and Ixodes scapularis and divergence times from Vieira and Rozas (2011). First, we estimated the global λ (the number of gene births and deaths per existing gene per million years) (L-GR-ML) and second, we estimated the birth (β) and death (δ) rates separately (BDI-GR-ML). Furthermore, we used the formulae of Vieira et al. (2007) to calculate birth and death rates from information on the inferred number of duplications and losses (that is, pseudogenization) within each branch of the ant species tree by adding each event separately in the summation. As our results show, the ant-specific expansions have mainly taken place separately within the lineages and the ancestral ants have had at least seven CSP genes corresponding to the inferred orthologous groups. For estimating the birth rate, we let the ancestral number in ants range from eight to eleven, assuming that the duplications in ants are species specific, except for several duplications in the ancestral leafcutters (Supplementary Figure 1). We estimated the losses on the basis of pseudogenes. This approach underestimates the rates as it does not correct for gains and losses that have occurred without any trace in the data.

Results

Size and dynamics of the CSP gene family in ants

The CSP gene family has expanded in ants compared to four copies in Drosophila and six in the honeybee. We identified a total of 11–21 functional CSP genes per ant species (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Data set 1), the predicted length of the produced protein ranging from 100 to 130 amino acids with a signal peptide. Three of the 97 annotated genes were unusually short (length 60–80 amino acids) but they were classified as functional based on support from gene models in the Hymenoptera Genome Database (Munoz-Torres et al., 2011). Additionally, we detected several pseudogenes (0–6 per species, the highest numbers being in the leafcutting ants A. echinatior and A. cephalotes) marked by inframe stop codon mutations or frame shifts or usually both, and several partial gene fragments (length <20 amino acids). S. invicta has the highest number of CSP genes adding up to total of 21 intact and two pseudogenes, and P. barbatus and H. saltator have the lowest numbers of 11 intact CSP genes. We included the pseudogenes when constructing the phylogenetic gene tree, but left them out from further sequence analyses. The partial gene fragments were not used in any analysis. These could, for example, represent additional pseudogenes or allelic variation of the already assembled genes.

The alignment of ant CSPs along with four Drosophila and six honeybee genes had a GUIDANCE score of 0.84 (1 being the highest and 0 lowest). The gene tree shows seven groups of orthologous genes and a cluster of ant-specific duplications (Figures 2a and b). The orthologous groups are conserved and these genes have been retained in all the ants (always one functional gene per species). Only one of the seven groups contains one pseudogene. Even though the produced gene tree is unrooted, it seems reasonable to conclude that each of the seven orthologous groups forms a distinct monophyletic clade (CSP1 to CSP7 in ants, Figure 2a), which are all well supported with bootstrap values ranging from 84 to 100%. Five of these orthologous clades include also an A. mellifera gene, indicating that these genes have been duplicated already in the common ancestor of ants and bees.

In addition to the seven orthologous groups, there are several ant-specific duplications most likely expanded from a single ancestral source (Figure 2b). This clade is well supported (98% bootstrap) including one of the orthologous gene groups (ant CSP7) at the base. Many bootstrap values within this expansion are very low. Nevertheless, there are several well-supported species-specific gene clusters. These include one group with eight S. invicta genes, one of which is a pseudogene (SinvCSP8, SinvCSP9, SinvCSP10, SinvCSP12, SinvCSP13, SinvCSP19, SinvCSP20, SinvCSP23P, Figure 2b), another group of five genes in S. invicta (SinvCSP11, SinvCSP15, SinvCSP16, SinvCSP17, SinvCSP21, Figure 2b) and several single duplications like CfloCSP8 and CfloCSP11, LhumCSP10 and LhumCSP11 along with HsalCSP8 and HsalCSP9. Furthermore, the genes of the leafcutting ants are mainly in small groups of 8, 5, 4 and 3 genes, commonly in such a way that the genes of the two species (A. echinatior and A. cephalotes) form a pair. These patterns indicate that the ant-specific duplications have most likely originated from one or only few ancestral copies, and the gene family has expanded separately in different lineages. The ant genomes have not been fully assembled to correspond to actual chromosomes, still some of the ant-specific duplicates show tandem structure, one contig containing one–five CSP genes within one species. The species-specific duplications such as those of S. invicta are to large extent situated in same scaffolds (Supplementary Table S1).

The rate of turnover (the number of gene births and deaths per existing gene per million years) for the CSP gene family is λ=0.0043 when calculated using the data from seven ant species and 12 other arthropods analyzed earlier by Vieira and Rozas (2011), namely D. melanogaster, D. virilis, D. erecta, D. ananassae, A. gambiae, B. mori, T. castaneum, A. mellifera, P. humanus, A. pisum, D. pulex and I. scapularis. When estimated separately, the birth rate is 0.0043 and the death rate 0.0045. These estimates use no information about the orthology relationships, and the calculation therefore implicitly assumes that the ancestral number of genes has been intermediate and has increased in some lineages and decreased in others. For this reason, BadiRate assumes less duplications and more losses than the actual gene tree of ants indicates. We therefore also estimated the birth and death rates using the formulae applied from Vieira et al. (2007) (Supplementary Figure S1). The ancestral number in ants was assumed to be within the range of 8–11. Most duplications were assumed to be species specific, except for several duplications in the ancestor of leafcutters. With these assumptions, the estimated birth rate in ants is within 0.0038–0.0054 births per gene per million years, and the death rate 0.0012 (Supplementary Figure S1).

Sequence evolution of CSP genes in ants

The nucleotide sequence alignment of the functional ant genes had a GUIDANCE score of 0.92, indicating confident alignment. This alignment was used in further sequence analyses. Within each ant species the average estimated amino acid divergence per site among CSP genes is very similar, and range from 1.1 in A. cephalotes to 1.3 in L. humile. Assuming that synonymous substitutions accumulate at a fairly constant rate, the dN/dS ratio measures the relative rate of evolution at the protein level. The estimated relative rate of protein evolution (dN/dS) in ant CSP genes varies from low (0.09) to high (0.38) depending on ant species in question (Table 1). The CSP proteins are more conservative in T. castaneum, B. mori and A. mellifera (dN/dS=0.006–0.05) than in any of the ants. Of insects only A. gambiae CSP genes have a dN/dS ratio (0.13) comparable to some of the ant species. Combining the CSP genes from all the ant species, the dN/dS ratio is, on average, 0.40 when calculated by SLAC and 0.33 when calculated by codeml (Table 1). Estimates from codeml are consistently lower than estimates from SLAC (Table 1). In the following results, only dN/dS estimates obtained with codeml are discussed, but both SLAC and codeml estimates are reported in the tables. The free-ratio model of codeml fits the data better than the model of single dN/dS ratio for all branches (M0) (likelihood ratio test value 1633.5, df=191, P<0.001) indicating different rates of sequence evolution along the gene tree of ant CSPs.

To investigate whether the seven groups of orthologous genes (Figure 2a) have been under different selection regime than the ant-specific expansion (Figure 2b), we estimated the dN/dS ratio for these two groups separately. Within the different orthologous groups (ant CSP1–7) the average estimated amino acid divergence per site ranges from 0.10 to 0.52. The pairwise divergence among all the orthologous genes ranges from 0.02 to 2.6 and the ant-specific duplications have pairwise amino acid differences ranging from 0.13 to 1.6. Overall, the ant-specific expansion has a significantly higher average dN/dS ratio (0.51) than the genes in the orthologous groups (0.21). When the dN/dS ratios are calculated for each orthologous group separately, they vary from 0.07 to 0.27 (Table 2). S. invicta has a large number of lineage-specific duplicates and it also has a high dN/dS ratio. To exclude the possibility that ant-specific duplicates are evolving fast simply because they include several S. invicta genes, we calculated dN/dS separately for this expanded group excluding S. invicta. This does not change the result (dN/dS=0.41 for ant-specific duplicates after removing S. invicta genes). Rather it seems that the mean dN/dS ratio in S. invicta is high because it contains many fast evolving recent duplicates.

Selection in ant CSP genes

Rapid sequence evolution can reflect positive selection or alternatively relaxation from purifying selection. To investigate the causes of different dN/dS ratios in the orthologous groups in contrast to expanded ant-specific genes, we analyzed potential selection with HyPhy and PAML (Table 3). The results from HyPhy indicate that the selective pressures differ between these two groups of genes in such a way that there are more sites under purifying selection in the orthologous groups (41% of codons under purifying selection) than in the expanded ant-specific group (21% of codons under purifying selection). Both SLAC and FEL models give consistent results, SLAC being more conservative. No indication of positively selected sites in the orthologous group was detected either by SLAC and FEL models in HyPhy, or by a comparison of M1a and M2a in PAML. In stark contrast, several sites are under positive selection in the ant-specific group. Fourteen positions in total are indicated to be under positive selection by at least one of the methods SLAC, FEL and M2a (Table 3). Some of these sites are identified by all three programs, some by only one or two. Inference of positive selection does not reflect fast-evolving S. invicta genes as their removal does not change the overall result.

We modeled the molecular structure of ant CSPs using the protein structure from M. brassicae (PDB ID 1n8v) as template. We used one of the sequences (HsalCSP11) in the ant-specific expansion, which according to Phyre2 had 100% confidence, 80% coverage, 31% identity with the M. brassicae model at amino acid level. HsalCSP11 consists of six α-helices and has a cavity with several openings (Figure 3), like the M. brassicae CSP. Three residues in M. brassicae CSP (Y26, W81 and W94) were suggested to be crucial for binding substrates (Campanacci et al., 2003). These three residues are highly conserved in the ant sequences, two of them showing no variation and one (MbraCSP W94) being mutated only in two sequences. In M. brassicae, the amino acids located at the openings of the binding pocket were suggested to have a role in substrate binding (Campanacci et al., 2003). None of these residues are among the positively selected amino acids inferred in ants, but also the openings to the binding pocket in the ant model are on different locations. One of the predicted cavity openings in HsalCSP11 shows two positively selected amino acids (M73 and I92), whereas others reside largely on the surface of the molecule.

The mode of evolution in the CSP genes that have a role in nestmate recognition

The possible role of CSPs in nestmate recognition has been studied in three of the taxa used here. Both C. japonicus (congeneric with C. floridanus) and L. humile use cuticular hydrocarbons for nestmate recognition, and in both species the major protein expressed in the antennae is a CSP (Ishida et al., 2002; Ozaki et al., 2005). In C. japonicus, this protein was shown to bind the cuticular hydrocarbons used in nestmate recognition. The protein in C. japonicus differs from that in C. floridanus in only two amino acids and the gene tree shows that the antennal CSPs of Camponotus and Linepithema belong to the same orthologous group (ant CSP7) (Figure 2). This orthologous group CSP7 has an overall dN/dS ratio similar to other orthologous groups (dN/dS=0.13) and no sites are indicated to evolve under positive selection by SLAC, and the model including positive selection does not fit the data significantly better in M1a–M2a comparison in codeml. The third possible involvement of CSP in nestmate recognition is in S. invicta, where SinvCSP19 codes for the major protein expressed in antennae (González et al., 2009). This gene (SinvCSP19) belongs to the largest S. invicta-specific expansion including eight genes, one of which is a pseudogene. Restricting the analysis to the seven functional genes, the dN/dS ratio within this clade is exceptionally high with a mean 1.3, but no positively selected sites are found with the SLAC or FEL model of HyPhy. However, when analyzed with codeml, the model allowing positive selection fits the data better than the neutral model (M1a versus M2a, likelihood ratio test 15.56, df=2, P<0.001) and suggests that 24 sites are under positive selection, seven of which have probabilities over 90%.

Discussion

Our findings on CSP gene family evolution in ants agree with reports on highly dynamic evolution of animal chemosensory genes by birth-and-death model (Nei et al., 2008; Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009), but depart from those studies that found insect CSPs to be a conserved gene family (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009). Earlier studies have shown that many insect CSPs are ancient and shared by different insect orders (Zhou et al., 2006; Gong et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009). However, including data from several arthropod genomes led Vieira and Rozas (2011) to conclude that the CSP family is more dynamic in terms of gene loss and gain than previously found. That result was largely based on branches covering long evolutionary time scales (up to 700 My) and the authors considered it desirable to have genomic information from species that are more closely related. Our present data help to fill that gap as the seven ant species have diverged from each other during the last 130 My. Furthermore, several studies have overlooked sequence evolution or have failed to detect positive selection in gene families involved in chemosensation (Forêt et al., 2007; Vieira et al., 2007; Gardiner et al., 2008; Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010). In contrast, our results highlight the rapid evolution and positive selection in the most recent duplicates of ant CSP genes.

Expansion of CSP genes in ants

Our manual annotation of CSP genes in the seven ant genomes identified 11–21 functional CSP genes per species. Ants thus have CSP gene families that range from medium sized to one of the largest found in insects. The number is clearly high compared to the six genes in the closest analyzed relative, the honeybee A. mellifera. The seven well-supported orthologous groups have been retained in all the ant species and five of them can be found from the honeybee, indicating broad phylogenetic conservation of these genes. The two orthologous groups present in all the ants but not in the honeybee suggest that these genes have originated after the split of ant and bee lineages (ca. 163.5 My) or that the genes have been lost in the honeybee. The additional expansions have clearly taken place separately within the ant lineages.

This is seen in the gene tree where genes from a single species, or from two closely related species in the case of leafcutting ants, cluster together. In Drosophila, the overall number of chemoreceptor genes (OR and GR) within species correlates with the genome size and is thus partly explained by large-scale genomic changes (Gardiner et al., 2008). Similarly, in ants the total genome size correlates with the number of CSP genes (functional and pseudogenes) significantly (r=0.81, df=5, P<0.05). This parametric correlation is greatly influenced by S. invicta that has the largest genome (484 Mb) (Wurm et al., 2011) and the largest number of CSP genes. Removing S. invicta reduces correlation to r=0.69 that is not quite significant, but the sample size is also small. However, irrespective of the genome size, the predicted total number of genes per genome is very similar in all the ants, also in S. invicta, therefore the positive correlation cannot apply to all the gene families. We can also note that compared to ants the honeybee genome is intermediate in size. The difference in the number of CSP genes in bees and ants is thus not simply explained by large-scale genomic changes. As a large proportion of the ant CSP genes belong to the group that seems to have expanded independently in different ant lineages, we can conclude that the gene family has expanded in ants.

Gene families expand through gene duplication and contract through gene loss or pseudogenization. The overall turnover rate (number of gene gains and losses per gene per My) of the CSP gene family estimated here in 19 arthropods by maximum likelihood (λ=0.0043) is higher than previous estimates of birth (0.0028) and death (0.0007) (Vieira and Rozas, 2011). The differences can stem from the fact that we did not use information of the orthology relationships in our estimate as such information is partial for the ants, and therefore not suitable for the current maximum likelihood methods. With information only on the number of genes in each species, the resulting gains and losses deduced by maximum likelihood do not reliably reflect the gene tree of ant CSPs. The birth (0.0038–0.0054) and death (0.0012) rates of ant CSPs calculated with the modified formulae of Vieira et al. (2007) are more reliable, even though they probably underestimate the gene turnover. All our estimates, especially those of birth rate, are higher than previously estimated for CSPs and higher than the average for all gene families in several organisms, the genome-wide estimates obtained with the program CAFE ranging from λ=0.002 in yeast to λ=0.0016 in mammals, λ=0.0012 in Drosophila (Demuth and Hahn, 2009) and λ=0.0010 in holometabolous insects (M Helmkampf personal communication). This means that there are more gene duplications and losses in CSP gene family than in gene families on average. Rapid turnover rates have been observed in other chemosensory gene families of many insects (Vieira et al., 2007; Gardiner et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2010) and the rate of turnover in CSP gene family falls well within the turnover rates estimated for Drosophila in OBP (λ=0.005), OR (λ=0.006) and GR (λ=0.011) gene families (Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009, estimated with program CAFE).

Interestingly, gene turnover is unevenly distributed among the ant CSP genes, the orthologous groups being conserved and having a slow rate of turnover as no new duplicates and only one pseudogene associate with these. In contrast, the genes specific to ants show higher turnover with new duplicates and many pseudogenes. The probability of gene duplication is likely to depend on the organization of the genes in the genome, and tandemly arranged duplicates increase the chance of further changes in the gene number. The available data show that some of the genes in the ant-specific expansion are linked in adjacent positions within species, suggesting evolution by tandem duplication. However, it is premature to conclude that the different turnover rates of orthologous groups compared to ant-specific expansion would simply result from different genomic arrangements as two of the conserved genes (CSP3 and CSP1 in ants) are tandemly located, but show no recent duplicates. Two pairs of the honeybee CSP genes (AmelCSP3 and 4, as well as AmelCSP5 and 6) are also located within a few kilobases from each other, yet the gene family has not expanded in bees. The repeated expansion of the CSP gene family in each ant lineage separately raises questions about the function of these genes and their possible role in adaptation. Are there any signs of adaptive evolution in the ant-specific expansions of CSP genes?

Two groups of genes with different evolutionary patterns

The seven orthologous groups and the expanded ant-specific group have contrasting modes of evolution, the ant-specific duplicates being more dynamic in several aspects. In addition to the slower turnover rate, the orthologous groups have been retained in all the ant species suggesting that their function is conserved. These orthologous genes are also more conserved at the sequence level (dN/dS=0.21) and show more sites under purifying selection than the expanded ant-specific duplicates (dN/dS=0.51). Moreover, this rapid evolution in the ant-specific expansion does not entirely reflect relaxed selection as several sites are indicated under positive selection. Both PAML and HyPhy give consistent results in that both methods suggest positive selection in the ant-specific duplicates, but not in the conserved orthologous groups.

There are also some differences between the results provided by the models in HyPhy and PAML. SLAC model in HyPhy gives consistently higher dN/dS ratios than codeml in PAML, a difference that can be expected when the underlying methods of estimation are different. Dramatically different results between SLAC and codeml are obtained when analyzing the S. invicta-specific clade containing the possible nestmate cue binder. SLAC does not find any indication of positive selection, whereas codeml suggests 24 sites under selection. Some confidence in codeml result is given by the fact that six of the sites are same as suggested to be under positive selection in the ant-specific group of genes (even when excluding the S. invicta specific expansion). Also the average dN/dS (1.3) of this S. invicta-specific expansion suggests positive selection. The orthologous group (CSP7 in ants) containing the proteins for binding cuticular hydrocarbons used as nestmate recognition cues in Camponotus and Linepithema does not show accelerated evolution or positive selection, and thus no signs of arms race with intruders. Interestingly, the nestmate cue binder in C. japonicus and L. humile is not orthologous with the putative nestmate cue binder of S. invicta, an observation that fits well with the hypothesis that different substances are used for nestmate recognition (González et al., 2009).

The genes that show higher rate of turnover also change more rapidly at sequence level in the ant CSP gene family, a result which agrees with a large-scale comparison of gene families in some other animals (Chen et al., 2010). Evolutionary rates have also been associated to other biological factors like gene essentiality (He and Zhang, 2006) and expression level (Pal et al., 2001), and gene families that are conserved in size have a higher proportion of essential genes and a higher level of gene expression and expression breadth (Chen et al., 2010). It remains to be shown whether such differences characterize also the two groups of CSP genes in ants.

Indication of positive selection in the expanded group of ant-specific genes suggests that these genes are involved in adaptation. Interestingly, the positively selected sites are not inside the protein molecule, but some are located at the cavity opening and some on the surface of the protein structure. This finding is in agreement with the earlier results that the binding pocket of CSPs is more conservative than the positions of the core protein (Forêt et al., 2007), but in contrast to results from the honeybee OBP genes, where the positively selected sites were located in the putative binding pocket (Forêt and Maleszka, 2006). Nevertheless, positively selected sites in ant CSP genes can have an effect on the interactions the mature protein has with other molecules like pheromones and other chemicals. The positively selected sites at the cavity opening could possibly affect which chemicals are bound. It has also been suggested that conformational changes in CSPs would trigger recognition in ORs (Campanacci et al., 2003). We can thus speculate that the positively selected sites may also have a role in the interaction between CSPs and ORs.

Evolution of ant CSP gene family in contrast to other insects

The evolution of gene families has often been discussed within the framework of three alternative models: concerted evolution, diversification and random birth-and-death model (genomic drift) (Nei and Rooney, 2005; Vieira et al., 2007). Several studies on chemosensory gene families have favored the model of birth and death evolution where new members of a gene family replace the lost copies, and this has also been suggested for CSPs Sánchez-Gracia et al., 2009. Focusing on details of functional properties and evolutionary dynamics of gene duplicates, Innan and Kondrashov (2010) list ten different models. Depending on the model, the new gene duplicates can evolve either under purifying selection if duplication confers a selective advantage or under relaxed purifying selection when no immediate advantage is conveyed. In some models, positive selection can be involved in some phases of the duplicate evolution. The data on ant CSP genes are partly compatible with the genomic drift model as there are both gains and losses of genes. However, this turnover is not evenly distributed across the gene family members. In addition, the CSP genes show repeated and independent expansion in different ant species and characteristics of adaptive diversification indicated by positive selection. A plausible explanation is that duplicates have experienced a period of relaxed purifying selection after which some sites have undergone positive selection and the proteins diversified in function. In a similar way, relaxed selection has been suggested to be precursor for phenotypic plasticity (Hunt et al., 2011) in the sense that sequences experiencing relaxed selection more readily take on new expression patterns.

In contrast to our findings, purifying selection is often identified as the main force in the evolution of insect chemosensory gene families with no or little indication of positive selection. This is the case in Drosophila OBP (Vieira et al., 2007), OR and GR (Gardiner et al., 2008), and in Acyrthosiphon pisum OBP and CSP (Zhou et al., 2010) gene families. The few exceptions of positive selection are offered by the honeybee OBP gene family where positive selection was detected in one subfamily (so-called C-clade) (Forêt and Maleszka, 2006), and the OR and GR genes in a pea aphid, where the most recent duplicate genes were found to evolve under positive selection (Smadja et al., 2009). One reason for contrasting results can be that commonly the selection analyses in chemosensory genes are restricted to orthologous genes, which are not expected to experience positive selection if they have a conserved function. It is likely that positive selection is detected more easily in recent duplicates because long-term exposure to purifying selection drowns the signal of episodic positive selection.

In conclusion, the ant CSP gene family evolves fast at both gene family level (λ) and at molecular level. In particular, the dN/dS ratios in the expanded ant-specific duplicates are exceptionally high. Our work underlines the observation that selective pressures are not uniform among the members of one gene family. The observation that ant-specific genes evolve faster than the older conserved genes, can be caused either by positive selection or relaxed purifying selection. Both explanations seem to apply as there is less purifying selection in the ant-specific duplicates than in the conserved orthologous genes. Still the ant-specific expansion is not evolving neutrally, but show signs of positive selection. Our data raises interesting question about the function of the expanded CSP genes in ants. Generally, insect CSPs are highly expressed in the sensillar lymph and, in vitro, capable of binding different components of pheromonal blends (Pelosi et al., 2006), but not all CSPs are restricted to chemosensory organs. Basal to ant-specific expansions is the orthologous CSP7, which in both L. humile and C. japonicus is conserved in the function of binding cuticular hydrocarbons used in ant chemical communication. If the ant-specific expansion has originated from the CSP7 or similar ancestral gene, as seems likely, the genes in ant-specific expansion could be adapted to chemosensory functions. Whereas the accelerated evolution coupled with positive selection suggests adaptive role of recently duplicated CSPs in ants, expression studies will shed light if the function of these genes is indeed related to chemosensation.

Data archiving

Data is found as Supplementary Material and has also been deposited in the Dryad repository: doi:10.5061/dryad.7sh4r.

References

Bielawski JP, Yang Z (2005). Maximum likelihood methods for detecting adaptive protein evolution. In: Nielsen R, (ed) Statistical Methods in Molecular Evolution. Springer: New York, USA.

Bonasio R, Zhang G, Ye C, Mutti S, Fang X, Qin N et al (2010). Genomic comparison of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. Science 329: 1068–1031.

Brady SG, Schultz TR, Fisher BL, Ward PS (2006). Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18172–18177.

Campanacci V, Lartique A, Hällberg BM, Jones TA, Giudici-Orticoni MT, Tegoni M et al (2003). Moth chemosensory protein exhibits drastic conformational changes and cooperativity on ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5069–5074.

Chen FC, Chen CJ, Li WH, Chuang TJ (2010). Gene family size conservation is a good indicator of evolutionary rates. Mol Biol Evol 27: 1750–1758.

Demuth JP, Hahn MW (2009). The life and death of gene families. BioEssays 31: 29–39.

Edgar RC (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797.

Engsontia P, Sanderson AP, Cobb M, Walden KKO, Robertson HM, Brown S (2008). The red flour beetle's large nose: an expanded odorant receptor gene family in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 38: 387–397.

Forêt S, Maleszka R (2006). Function and evolution of a gene family encoding odorant binding-like proteins in a social insect, the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Genome Res 16: 1404–1413.

Forêt S, Wanner KW, Maleszka R (2007). Chemosensory proteins in the honey bee: insights from the annotated genome, comparative analyses and expressional profiling. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 37: 19–28.

Gardiner A, Barker D, Butlin RK, Jordan CJ, Ritchie MG (2008). Drosophila chemoreceptor gene evolution: selection, specialization and genome size. Mol Ecol 17: 1648–1657.

Gong DP, Zhang H, Zhao P, Lin Y, Xia QY, Xiang ZH (2007). Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 37: 266–277.

González D, Zhao Q, McMahan C, Velasquez D, Haskins WE, Sponsel V et al (2009). The major antennal chemosensory protein of red imported fire ant workers. Insect Mol Biol 18: 395–404.

He X, Zhang J (2006). Higher duplicability of less important genes in yeast genomes. Mol Biol Evol 23: 144–151.

Holman L, Jorgensen CG, Nielsen J, d́Ettorre P (2010). Identification of an ant queen pheromone regulating worker sterility. Proc R Soc B 277: 3793–3800.

Hunt BG, Ometto L, Wurm Y, Shoemaker D, Yi SV, Keller L et al (2011). Relaxed selection is a precursor to the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 15936–15941.

Innan H, Kondrashov F (2010). The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat Rev Genet 11: 97–108.

Ishida Y, Chiang V, Leal WS (2002). Protein that makes sense in the Argentine ant. Naturwissenschaften 89: 505–507.

Jordan G, Goldman N (2012). The effects of alignment error and alignment filtering on the sitewise detection of positive selection. Mol Biol Evol 29: 1125–1139.

Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T (2005). MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 511–518.

Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE (2009). Protein structure prediction on the web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc 4: 363–371.

Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SDW (2005a). Datamonkey: rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics 21: 2531–2533.

Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SDW (2005b). Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol 22: 1208–1222.

Lahav S, Soroker V, Hefetz A, Vander MRK (1999). Direct behavioral evidence for hydrocarbons as ant recognition discriminators. Naturwissenschaften 86: 246–249.

Leal WS, Chen AM, Ishida Y, Chiang VP, Erickson ML, Morgan TI et al (2005). Kinetics and molecular properties of pheromone binding and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 5386–5391.

Librado P, Vieira FG, Rozas J (2011). BadiRate: estimating family turnover rates by likelihood-based methods. Bioinformatics 28: 279–281.

Löytynoja A, Goldman N (2005). An algorithm for progressive multiple alignment of sequences with insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 10557–10562.

Maleszka J, Forêt S, Saint R, Maleszka R (2007). RNAi-induced phenotypes suggest a novel role for a chemosensory protein CSP5 in the development of embryonic integument in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Dev Genes Evol 217: 189–196.

Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C et al (2011). CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D225–D229.

Moreau CS, Bell CD, Vila R, Archibald SB, Pierce NE (2006). Phylogeny of the ants: Diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science 312: 101–104.

Munoz-Torres MC, Reese JT, Childers CP, Bennett AK, Sundaram JP, Childs KL et al (2011). Hymenoptera genome database: integrated community resources for insect species of the order Hymenoptera. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D658–D662.

Nei M, Niimura Y, Nozawa M (2008). The evolution of animal chemosensory receptor gene repertoires: roles of chance and necessity. Nature Rev Genet 9: 951–963.

Nei M, Rooney AP (2005). Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families. Annu Rev Genet 39: 121–152.

Nozawa M, Nei M (2007). Evolutionary dynamics of olfactory receptor genes in Drosophila species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7122–7127.

Nygaard S, Zhang G, Schiøtt M, Li C, Wurm Y, Hu H et al (2011). The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. Genome Res 21: 1339–1348.

Ozaki M, Wada-Katsumata A, Fujikawa K, Iwasaki M, Yokohari F, Satoji Y et al (2005). Ant nestmate and non-nestmate discrimination by a chemosensory sensillum. Science 309: 311–314.

Pal C, Papp B, Hurst LD (2001). Highly expressed genes in yeast evolve slowly. Genetics 158: 927–931.

Pelosi P, Zhou JJ, Ban LP, Calvello M (2006). Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1658–1676.

Penn O, Privman E, Ashkenazy H, Landan G, Graur D, Pupko T (2010). GUIDANCE: a web server for assessing alignment confidence scores. Nucleic Acids Res 38: W23–W28.

Privman E, Penn O, Pupko T (2012). Improving the performance of positive selection inference by filtering unreliable alignment regions. Mol Biol Evol 29: 1–5.

Sackton TB, Lazzarro BP, Schlenke TA, Evans JD, Hultmark D, Clark AG (2007). Dynamic evolution of the innate immune system in Drosophila. Nature Genet 39: 1461–1468.

Schrider DR, Hahn MW (2010). Gene copy-number polymorphism in nature. Proc R Soc B 277: 3213–3221.

Smadja C, Canbäck B, Vitalis R, Gautier M, Ferrari J, Zhou JJ et al (2012). Large-scale candidate gene scan reveals the role of chemoreceptor genes in host plant specialisation and speciation in the pea aphid. Evolution 66: 2723–2738.

Smadja C, Shi P, Butlin RK, Robertson HM (2009). Large gene family expansions and adaptive evolution for odorant and gustatory receptors in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Mol Biol Evol 26: 2073–2086.

Smith CD, Zimin A, Holt C, Abouheif E, Benton R, Cash E et al (2011). Draft genome of the globally widespread and invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5673–5678.

Smith CR, Smith CD, Robertson HM, Helmkampf M, Zimin A, Yandell M et al (2011). A draft genome of the red harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex barbatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5667–5672.

Stamatakis A (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690.

Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J (2008). A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol 57: 758–771.

Suen G, Teiling C, Li L, Holt C, Abouheif E, Bornberg-Bauer E et al (2011). The genome sequence of the leaf-cutter ant Atta cephalotes reveals insights into its obligate symbiotic lifestyle. Plos Genet 7: e1002007.

Swanson WJ, Vacquier VD (2002). Rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nature Rev Genet 3: 137–144.

Sánchez-Gracia A, Vieira FG, Rozas J (2009). Molecular evolution of the major chemosensory gene families in insects. Heredity 103: 208–216.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28: 2731–2739.

Vieira FG, Rozas J (2011). Comparative genomics of the odorant-binding and chemosensory protein gene families across the Arthropoda: origin and evolutionary history of the chemosensory system. Genome Biol Evol 3: 476–490.

Vieira FG, Sánchez-Gracia A, Rozas J (2007). Comparative genomic analysis of the odorant-binding protein family in 12 Drosophila genomes: purifying selection and birth-and-death evolution. Genome Biol 8: R235.

Vosshall LB, Stocker RE (2007). Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annu Rev Neurosci 30: 505–533.

Wurm Y, Wang J, Riba-Grognuz O, Corona M, Nygaard S, Hunt BG et al (2011). Genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5679–5684.

Xu YL, He P, Zhang L, Fang SQ, Dong SL, Zhang YJ et al (2009). Large-scale identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins from expressed sequence tags in insects. BMC Genomics 10: 632.

Yang ZH (2007). PAML 4: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1586–1591.

Zhou JJ, Kan Y, Antyoniw J, Pickett JA, Field LM (2006). Genome and EST analyses and expression of a gene family with putative functions in insect chemoreception. Chem Senses 31: 453–465.

Zhou JJ, Vieira FG, He XL, Smadja C, Liu R, Rozas J et al (2010). Genome annotation and comparative analyses of the odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. Insect Mol Biol 19: 113–122.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Biocenter Oulu Graduate School (JK), the Center of Excellence in Biological Interactions, Academy of Finland (grant 122210 to PP), the Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters (PP), BBSRC (grant number BB/K004204 to YW) and an ERC grant to Laurent Keller (YW). Some computation was performed at the vital-IT Center for high-performance computing (http://www.vital-it.ch). We thank Martin Helmkampf for discussions on gene turnover rates, Julien Roux for discussions on estimation of dN/dS, Ari Löytynoja for discussions on alignment and Heli Havukainen for guidance in protein modeling. We thank Lumi Viljakainen and Kalle Trontti for discussion and comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Heredity website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kulmuni, J., Wurm, Y. & Pamilo, P. Comparative genomics of chemosensory protein genes reveals rapid evolution and positive selection in ant-specific duplicates. Heredity 110, 538–547 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2012.122

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2012.122

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Host-plant adaptation as a driver of incipient speciation in the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2022)

-

De novo transcriptome assembly and its annotation for the black ant Formica fusca at the larval stage

Scientific Data (2018)

-

Antennal RNA-sequencing analysis reveals evolutionary aspects of chemosensory proteins in the carpenter ant, Camponotus japonicus

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Si-CSP9 regulates the integument and moulting process of larvae in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Expression Analysis and Binding Assays in the Chemosensory Protein Gene Family Indicate Multiple Roles in Helicoverpa armigera

Journal of Chemical Ecology (2015)