Abstract

A conditionally replicative adenovirus is a novel anticancer agent designed to replicate selectively in tumor cells. However, a leak of the virus into systemic circulation from the tumors often causes ectopic infection of various organs. Therefore, suppression of naive viral tropism and addition of tumor-targeting potential are necessary to secure patient safety and increase the therapeutic effect of an oncolytic adenovirus in the clinical setting. We have recently developed a direct selection method of targeted vector from a random peptide library displayed on an adenoviral fiber knob to overcome the limitation that many cell type-specific ligands for targeted adenovirus vectors are not known. Here we examined whether the addition of a tumor-targeting ligand to a replication-competent adenovirus ablated for naive tropism enhances its therapeutic index. First, a peptide-display adenovirus library was screened on a pancreatic cancer cell line (AsPC-1), and particular peptide sequences were selected. The replication-competent adenovirus displaying the selected ligand (AdΔCAR-SYE) showed higher oncolytic potency in several other pancreatic caner cell lines as well as AsPC-1 compared with the untargeted adenovirus (AdΔCAR). An intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR-SYE significantly suppressed the growth of AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors, and an analysis of adenovirus titer in the tumors revealed an effective replication of the virus in the tumors. Ectopic liver gene transduction following the intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR-SYE was not increased compared with the AdΔCAR. The results showed that a tumor-targeting strategy using an adenovirus library is promising for optimizing the safety and efficacy of oncolytic adenovirus therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses, which are genetically programmed to replicate within tumor cells but not in normal cells and directly induce cytotoxic effects via cell lysis, are currently being explored in preclinical and clinical studies of various cancers such as head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer and malignant glioma.1, 2, 3 For this purpose, the variety of oncolytic viruses such as adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, influenza virus, Newcastle disease virus, poliovirus, reovirus, vaccinia virus and vesicular virus have been developed.1, 3 In the context of conditionally replicative adenoviruses (CRAds), two strategies have been employed to restrict virus replication to target cells. One strategy is to introduce a mutation in the E1 region, and the function of these missing genes may be complemented by genetic mutation in tumor cells such as p53 mutation. An alternative strategy is to construct viruses in which the transcription of E1 genes is restricted to tumor cells by either a tumor or a tissue-specific promoter.2, 3 However, a leak of an oncolytic adenovirus from the virus-replicating tumors into systemic circulation often causes ectopic transduction of vital organs such as the liver.2 Therefore, the suppression of naive viral tropism is needed to reduce the undesirable infection of nontarget normal tissues. Importantly, the antitumor effect of oncolytic virus is determined by the capacity to infect tumor cells.4, 5, 6 Thus, the addition of a tumor-targeting potential to an oncolytic adenovirus ablated for naive tropism may enhance its therapeutic index.2, 7

Among strategies to modify the tissue tropism of adenoviruses, the engineering of the adenoviral genome is promising, because the targeting specificity is made inherent to the viral genome and thus maintained on replication.8 Although RGD motif and polylysine residues have been incorporated into the adenovirus fiber knob to enhance the gene transduction efficacy of a tumor, because the loss of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) expression is sometimes associated with malignant progression,9 those motifs also significantly enhanced gene transduction of normal tissues.6, 10 Proper targeting ligands on the cells of interest are still generally not known, which impedes the application of fiber-modified adenovirus vectors for oncolytic virus therapies.

Although a phage display library has been used to identify targeting peptide motifs, the incorporation of the peptides selected by phage display into the adenoviral capsid has not been successful in developing targeted vectors except for a few cases,11, 12, 13 possibly due to the peptide-induced conformational change of the virus capsid and the loss of specificity and affinity of ligand-receptor binding.14 We have recently developed a novel system for producing adenoviral libraries displaying a variety of peptides on the HI-loop of the fiber knob and established a procedure to select an adenoviral vector with high infectivity in target cells.15 As the binding affinity might be determined by the overall conformation of a modified fiber and not by inserted peptides alone, the selection of targeting peptides is highly useful in the context of the adenoviral capsid. In this study, first, the adenovirus library was screened for high affinity to a pancreatic cancer cell line (AsPC-1). Second, we examined whether the selected tumor-targeting ligand could enhance the tumor-specific oncolytic activity of a replication-competent adenovirus ablated for CAR binding. Our vector is a replication-competent adenovirus with a wild E1 gene, and not a conventional CRAd. However, the adenovirus displaying the selected peptide showed infectivity preferentially against tumor cells compared with normal cells and organs, and tumor cytolysis was closely related to the infectivity. Therefore, the strategy of the tumor-targeted virus with the wild replication activity may be included in the category of oncolytic virus therapy. The results showed that a tumor-targeting strategy using an adenovirus library is a promising strategy for optimizing oncolytic virus therapy, for which this is the first report of a targeted oncolytic virus developed by an unbiased library-based approach.

Results

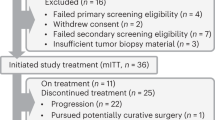

Ectopic liver transduction after intratumoral injection of adenovirus with a wild-type fiber

To examine whether the intratumoral replication of adenovirus with a wild-type fiber causes the ectopic infection of the liver, enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression was assessed in the frozen sections of the liver 2 and 6 days after the direct injection of adenoviruses into AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors. Under a fluorescence microscope, the EGFP-positive cells were not recognized at day 2 in the whole liver sections examined, whereas EGFP-positive cells were detected at day 6 and the number of positive cells in the liver of mice injected with Ad-EGFP was approximately 8.0-fold higher than that of AdΔCAR-EGFP (Figure 1). A replication-incompetent adenovirus with a wild-type fiber (AdΔE1-EGFP) did not show any EGFP expression in the liver at day 6 also. As the results confirmed that the wild-type fiber results in ectopic liver transduction at a significant higher level compared with CAR-binding mutant, we focused on the adenovirus ablated for CAR binding as a backbone vector in the following analyses.

Ectopic liver transduction after intratumoral injection of adenoviruses. Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-positive cells were examined under fluorescence microscope in frozen sections of the liver 6 days after intratumoral injection with AdΔE1-EGFP, Ad-EGFP, AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE. EGFP-positive cells were counted in 10 high power fields, and mean±s.d. are presented.

Selection of adenovirus library clones targeting AsPC-1 cells

To identify the peptides displayed on the fiber knob that produce higher transduction efficiency in AsPC-1 cells, the cells were infected with a peptide-display adenovirus library as described.15 Amplified and expanded adenoviruses on AsPC-1 cells were recovered after three rounds of selection, and the DNA region containing oligonucleotide inserts was amplified by PCR. DNA sequencing of the PCR products revealed enrichment of mainly two peptides, IVRGRVF (58% of the sequenced PCR fragments) and SYENFSA (38%; Table 1).

To examine whether gene transduction is enhanced by the selected peptides, AsPC-1 cells were infected with EGFP-expressing targeted vectors displaying either of the peptides on the fiber knob but ablated for CAR binding (AdΔCAR-IVR and AdΔCAR-SYE; Supplementary Figure 1), and EGFP-positive cells were counted under microscope 24 h after the infection. The numbers of EGFP-positive cells were 2.6- and 4.3-fold higher in AdΔCAR-IVR- and AdΔCAR-SYE-infected AsPC-1 cells than in untargeted adenovirus (AdΔCAR)-infected cells, respectively (Figure 2a, left and middle). Flow cytometry showed that AdΔCAR-SYE and AdΔCAR-IVR resulted in a significantly higher frequency of EGFP-positive cells than AdΔCAR (Figure 2a, right). As AdΔCAR-SYE showed higher gene transduction in AsPC-1 cells than AdΔCAR-IVR by EGFP-positive cell counting, SYENFSA sequence was employed in the following analyses.

Infectivity of various cell lines with the adenovirus displaying the selected peptide. The 1 × 104 cells were infected with adenoviruses at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 in 96-well plates, and 24 h later the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-positive cells in the wells were counted under fluorescence microscope. The 1 × 105 cells were infected with adenoviruses at MOI of 30 in 6-well plates, and 24 h later the flow cytometry was carried out using FACScan systems (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to analyze the frequency of EGFP-positive cells. (a) Infectivity of AsPC-1 cells with adenovirus vectors ablated for coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) binding. Left: representative photographs of EGFP-expressing cells ( × 100 original magnification). Middle: number of EGFP-positive cells counted per well in 96-well plates under microscope. The assays (carried out in eight wells) were repeated a minimum of two times and mean±s.d. are presented. Right: frequency of EGFP-positive cells by flow cytometry. (b) Relative number of EGFP-positive cells after infection of adenovirus vectors ablated for CAR binding in various cell lines. Left: relative number of EGFP-positive cells (the number of EGFP-positive cells infected with AdΔCAR-SYE/AdΔCAR) counted under fluorescence microscope. The statistical differences between the number of EGFP-positive cells infected with AdΔCAR-SYE and with AdΔCAR were as follows: BxPC-3; P=0.0015, AsPC-1; P=0.000013, Panc-1; P=0.000080, MIAPaCa-2; P=0.000013, PSN-1; P=0.41, U138MG; P=0.41, PC3; P=0.11, human umbilical vascular endotherial cells (HUVEC); P=0.20, human pancreatic epithelial cells (HPE); P=0.25. Right: relative frequency of EGFP-positive cells (the frequency of EGFP-positive cells infected with AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP/that with AdΔCAR) by flow cytometry. The statistical differences between the frequency of EGFP-positive cells infected with AdΔCAR-SYE and that with AdΔCAR were as follows: BxPC-3; P=0.00000053, AsPC-1; P=0.000039, Panc-1; P=0.0000026, MIAPaCa-2; P=0.00029, PSN-1; P=0.079, U138MG; P=0.085, PC3; P=0.21, HUVEC; P=0.21, HPE; P=0.15.

The cell-type specificity of AdΔCAR-SYE was then examined by the counting of EGFP-positive cells in various cells. Gene transduction was significantly enhanced in BxPC-3 (6.9-fold), Panc-1 (3.5-fold) and MIAPaCa-2 (2.2-fold) cells, whereas the gene transduction by AdΔCAR-SYE was almost the same as AdΔCAR in PSN-1, U138MG, PC3 and human umbilical vascular endotherial cells (HUVEC; 0.98- to 1.4-fold; Figure 2b, left). Flow cytometry showed that AdΔCAR-SYE significantly enhanced gene transduction in BxPC-3 (5.9-fold), AsPC-1 (3.9-fold), Panc-1 (3.6-fold) and MIAPaCa-2 cells (2.5-fold; Figure 2b, right), which was closely consistent with the results of EGFP-positive cell counting (Figure 2b, left), suggesting that the SYENFSA sequence enhances adenovirus infectivity for a certain population of pancreatic cancer. Ad-EGFP showed higher gene transduction efficiency in BxPC-3 (10.5-fold), AsPC-1 (12.5-fold), Panc-1(6.7-fold), MIAPaCa-2 (5.4-fold), PSN-1 (2.3-fold), HUVEC (4.1-fold) and pancreatic epithelial cells (3.0-fold) when compared with AdΔCAR (Figure 2b, right).

Biodistribution of AdΔCAR-SYE following intravenous administration

To examine the distribution of the adenovirus vector displaying the selected peptide, 2 × 109 PFU of AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP was injected into the mice via the tail vein, and 6 days later EGFP-positive focies were assessed in various organs. The numbers of EGFP-positive cells in the liver and spleen of mice injected with AdΔCAR-SYE were almost compatible with those of the mice injected with AdΔCAR, whereas the liver transduction of the adenovirus (Ad-EGFP) was approximately twofold higher than AdΔCAR and AdΔCAR-SYE (Figure 3a). The liver tropism of CAR-binding mutants based on adenovirus type 5 seems to differ with each mutation point in the fiber.16 The AdΔCAR contains 4-point mutations in the AB-loop, and Einfeld et al. also reported that the CAR binding-ablated vector with the same mutations showed two- to threefold decreases for liver transduction compared with the wild fiber after intravenous injection.17 The EGFP-positive cells were not detected in the lung, kidney and pancreas in all the groups of mice (Figure 3a). The results suggested that the SYENFSA sequence on the fiber knob does not change the biodistribution of an adenovirus vector ablated for CAR binding.

Gene transduction efficiency of various organs and subcutaneous tumors following intravenous injection of adenoviruses. The mice were injected intravenously with 2 × 109 PFU of adenoviruses (AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP; n=3), and then 5 μm slices of frozen sections at day 6 were examined under fluorescence microscopy ( × 200 original magnification). (a) Gene transduction efficiency of various organs. Left: representative photographs of the liver and spleen ( × 200 original magnification). Right: number of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-positive foci. EGFP-positive foci were counted in at least four fields at day 6 in various organs such as the lung, kidney, pancreas, spleen and liver, and mean±s.d. are presented. (b) Gene transduction efficiency of subcutaneous tumors. Left: representative photographs of the AsPC-1 and PC3 tumors ( × 200 original magnification). Right: number of EGFP-positive foci. EGFP-positive foci were counted in at least four fields at day 6 in tumors, and mean±s.d. are presented.

To evaluate the in vivo tumor targetability of AdΔCAR-SYE via a systemic administration, we injected the adenovirus via the tail vein in the AsPC-1 and PC3 tumor-bearing mice. Number of EGFP-positive foci 6 days after the injection showed that the gene transduction of AdΔCAR-SYE was 2.0-fold higher than AdΔCAR in AsPC-1 tumors, whereas the transduction of AdΔCAR-SYE was about half of that of AdΔCAR in PC3 tumors (Figure 3b), suggesting that the SYENFSA peptide enhances the infectivity of an adenovirus vector for AsPC-1 cells in vivo as well as in vitro. However, as the number of EGFP-positive cells in the AsPC-1 tumors was much smaller than that in the liver 24 h after the intravenous injection (data not shown), AdΔCAR-SYE does not seem promising as a vector for a systemic delivery.

In vitro cell killing by AdΔCAR-SYE

To examine whether the enhanced transduction of targeted adenovirus could result in effective cell killing for target cells, AsPC-1 cells were infected with viruses at various multiplicities of infection (MOIs). PC3 cells were used as a negative control, because the targeting ligand does not enhance their gene transduction (Figure 2b). Crystal violet staining, 7 days after the infection, revealed that the infection with AdΔCAR-SYE at MOI of 10 induced significant cell killing for AsPC-1 cells compared with AdΔCAR, whereas AdΔCAR-SYE showed the same cytolysis as AdΔCAR for PC3 cells (Figure 4a). Ad-EGFP resulted in cell lysis for AsPC-1 cells at MOI of 1. Infection of AsPC-1 cells with AdΔE1 induced cytotoxicity at MOI of 100. It has been reported that an adenovirus infection per se sometimes shows cytotoxicity in various cells by the induction of apoptosis and G2/M arrest via the p53-dependent or Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.18, 19

In vitro cell killing by infection of AdΔCAR-SYE. (a) Crystal violet staining of viable cells 7 days after infection. AsPC-1 and PC3 cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates and 24 h later the cells were infected with AdΔE1, AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 0.1, 1, 10 and 100. Seven days after the infection the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and stained with 1% crystal violet staining solution. (b) Cell killing by adenoviruses in various cell lines. The cells were infected with AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP at MOIs of 5, 10, 30, 50 and 100, and cell growth was determined by the in vitro cell proliferation assay 7 days after the infection. The assays (carried out in eight wells) were repeated a minimum of two times, and mean±s.d. are presented. The statistical differences between OD450 values of cells infected with AdΔCAR-SYE and those with AdΔCAR at MOI of 30 are presented.

Then, several cancer cell lines were infected with viruses, and 7 days later the cell growth was examined by in vitro cytotoxicity assay. Although a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation was observed in all cell lines by the infections of viruses, the AdΔCAR-SYE more effectively suppressed the growth of BxPC-3, AsPC-1, Panc-1 and MIAPaCa-2 cells as compared with the AdΔCAR. There was no significant difference in the cytotoxicity for PSN-1, U138MG and PC3 cells between AdΔCAR and AdΔCAR-SYE (Figure 4b). Ad-EGFP reduced the cell number more potently than AdΔCAR-SYE in BxPC-3, AsPC-1, Panc-1 and PSN-1 cells.

Oncolytic effect for cells should be dependent on the viral infectivity for the cells and the viral production within a cell. To compare the increase of adenovirus DNA, we infected AsPC-1 cells and PC3 cells with AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP. As the infectivity of AdΔCAR-SYE is similar to that of AdΔCAR in PC3 cells (Figure 2b), PC3 cells are suitable to estimate the viral production within a cell. In AsPC-1 cells, the adenovirus DNA rapidly increased in AdΔCAR-SYE-infected cells compared with AdΔCAR-infected cells, whereas the amount of adenovirus DNA was similar between the AdΔCAR-SYE- and AdΔCAR-infected PC3 cells even at day 9 (Supplementary Figure 2). The results demonstrated that the insertion of SYENFSA does not influence much the viral production within a cell, suggesting that the enhancement of the cell killing effect by AdΔCAR-SYE over AdΔCAR is due to the increase in virus transduction efficiency in each cell line (Figure 2b).

Tumor growth suppression by intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR-SYE

To investigate whether a targeting peptide displayed on the virus capsid could enhance the antitumor effect of a replication-competent adenovirus ablated for CAR binding, we directly injected subcutaneous AsPC-1 tumors with viruses at doses of 5 × 107∼5 × 108 PFU. The injection of AdΔCAR showed some antitumor effect against AsPC-1 tumors compared with the control virus AdΔE1, whereas the AdΔCAR-SYE more effectively suppressed tumor growth than AdΔCAR did, and almost complete regression of AsPC-1 tumors was observed in mice treated with a high dose (5 × 108 PFU) of AdΔCAR-SYE (Figure 5a). Ad-EGFP resulted in the largest antitumor effect. Although the AdΔCAR-SYE showed the same in vitro cytotoxic activity as AdΔCAR in PC3 cells (Figure 4b), the in vivo antitumor effect was larger for AdΔCAR than AdΔCAR-SYE in the PC3 subcutaneous tumors (Figure 5a).

Tumor growth suppression after intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR-SYE. (a) Tumor growth of AsPC-1 and PC3 subcutaneous tumors. The 0.5∼5 × 108 PFU of adenoviruses (AdΔE1, AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP) was directly injected once into the subcutaneous tumors (n=6∼7). Tumor volume was monitored, and mean±s.d. is presented on the days indicated. The statistical differences between tumor volumes infected with AdΔCAR-SYE and those with AdΔCAR are presented. (b) Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression in AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors. The intratumoral replication of adenoviruses (AdΔE1-EGFP, AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE) was assessed in the tumors. Frozen sections of tumors injected with each virus were examined at days 2, 4 and 6 under fluorescence microscope ( × 200 original magnification). (c) Immunodetection of adenoviral hexon proteins in the treated tumors. Six days after the intratumoral injection of adenoviruses (AdΔE1, AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE), the frozen sections of tumors were stained with anti-hexon antibody ( × 200 original magnification). (d) Increase of virus titer in the AsPC-1 tumors. 1 × 108 PFU of AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE was injected into the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors (n=3), which were collected 4 and 6 days after the virus injection. The 293-38.HissFv.rec cells were infected with the crude viral lysate of the tumors and 24 h after the infection EGFP-expressing cells were counted under florescence microscope to assess the titer of infectious virus. Titer of virus per tumor is presented.

To examine the virus replication in AsPC-1 tumors, the spread of EGFP expression was assessed in frozen sections of virus-injected tumors 2, 4 and 6 days after the intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or AdΔE1-EGFP at a dose of 2.5 × 108 PFU. The EGFP-positive cells were spread more extensively in the tumors injected with AdΔCAR-SYE compared with AdΔCAR (Figure 5b). Many EGFP-positive cells were detected in the AdΔE1-EGFP-injected tumors at day 2, but the number of positive cells rapidly decreased at day 6. To confirm that the spread of EGFP-positive cells indicates the presence of virus progeny in the tumor, an immunostaining to detect virus hexon was performed in sequential sections of tumor samples collected 6 days after the injection of the adenovirus vector. The adenovirus hexon-positive cells were detected in the tumor nodules with a locally concentrated pattern, and the area corresponded with the high EGFP signal (Figure 5c). Furthermore, to confirm the viral replication in the tumors, we injected 1 × 108 PFU of AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE into AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors and examined the amount of infectious virus in the tumors 4 and 6 days after the injection. The infection of 293-38.HissFv.rec cells with the crude viral lysate (CVL) of tumors showed that the titer of virus significantly increased in the AsPC-1 tumors at day 6 than at day 4, suggesting that the virus steadily proliferates in the tumors and tumor reduction is attributable to virus replication.

Ectopic infection of organs after intratumoral injection of targeted adenovirus vector

To evaluate whether the replication of targeted adenovirus in the tumor causes ectopic infection of organs, we analyzed adenovirus DNA by the PCR method in various organs and subcutaneous tumors 2 and 6 days after the intratumoral injection of AdΔE1, AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP at a dose of 2.5 × 108 PFU. The sensitivity of the PCR analysis was estimated to be about one copy per 102–103 genomes. When the replication-incompetent AdΔE1 was injected into the AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors, virus DNA was hardly detected in any of these normal organs except for the liver in a mouse at day 6. In the cases where AdΔCAR or AdΔCAR-SYE was injected, virus DNA was detected in AsPC-1 tumors but not in normal organs at day 2 (Figure 6a). Samples from organs such as the liver, spleen and lung in AdΔCAR-injected mice showed the adenovirus PCR bands at day 6, whereas the bands were recognized in the liver but not in the spleen and lung in the AdΔCAR-SYE-injected mice (Figure 6a). The adenovirus DNA was not detected from the organs of mice whose tumors were diminished before day 6. In contrast, the viral DNA was detected in many of the liver, spleen and lung 2 and 6 days after the injection of Ad-EGFP (Figure 6a).

Ectopic infection of normal organs after intratumoral injection of adenoviruses. (a) Detection of adenovirus DNA by PCR method. AsPC-1 subcutaneous tumors and organs (the liver, spleen and lung) were collected 2 and 6 days after the virus injection (AdΔE1, AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP), and DNA from tissues was subjected to PCR with the primers of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) binding domain in adenovirus fiber knob. (b) Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-positive cells in the liver. EGFP-positive cells were examined in frozen sections of the liver under fluorescence microscope 6 days after the direct injection of adenoviruses (AdΔE1-EGFP, AdΔCAR, AdΔCAR-SYE or Ad-EGFP) into AsPC-1 tumors ( × 200 original magnification). (Arrows: EGFP-positive cells.)

Moreover, to examine whether the detected PCR bands actually mean ectopic liver transduction, EGFP expression was assessed in the liver 2 and 6 days after the intratumoral injection of viruses. Although the EGFP-positive cells were not recognized in the liver of all animals at day 2, only a small number of EGFP-positive cells were sparsely detected in the liver at day 6, and the number of EGFP-positive cells following the intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR-SYE was not increased compared with that of AdΔCAR, which was less than 1/8 of Ad-EGFP (Figures 1 and 6b). An apparent discrepancy between the intensity of PCR bands and the frequency of EGFP-positive cells in the liver suggests that most of the DNA detected by PCR analysis is the partially degraded fragments of virus DNA.

Discussion

In this study, we screened a pancreatic cancer cell line with the peptide-display adenovirus library and identified candidate-targeting ligand sequences. A replication-competent adenovirus displaying the selected peptide showed an enhanced infectivity to the pancreatic cancer cell line and exerted a more potent cell killing in several other pancreatic cancer cell lines as well than the untargeted adenovirus. The intratumoral injection of the selected adenovirus resulted in effective tumor suppression without an increase of ectopic infection of organs.

The findings presented here would open new perspectives in the field of oncolytic virus therapy. The key prerequisite for an efficient oncolytic virus is the restriction of virus replication in tumor cells, and, so far, two major approaches have been examined for an oncolytic adenovirus: genetic complementation type (Type I) has a mutation in the E1 region, and the transcomplementation type (Type II) is designed to harbor a tumor/tissue-specific promoter in the upstream of the E1 gene.2, 3 Although the replication and spreading of such CRAds are restricted to tumor tissue in theory, several levels of additional safety devices are definitely required: the engineering of an adenovirus capsid to restrict infection for tumor cells is the first safety device and E1 manipulation to limit replication in the tumors is the second safety device.

An adenovirus displaying the selected peptide (AdΔCAR-SYE) significantly suppressed tumor growth, and complete regression of tumors was observed in some mice (Figure 5a). The reason for the strong antitumor effect may be that AdΔCAR-SYE has a wild-type E1 region, because the modification of this region usually reduces viral replication capacity in the cells.20, 21 Although we could select a peptide that provides a gene transduction approximately fourfold higher in target cells than an untargeted adenovirus, more efficient and tumor-specific targeting peptides could be isolated by a scaling up of the library size from the current 2 × 105 complexity level. The isolation of such high efficiency-targeting sequences may enable us to propose a new (that is, Type III) CRAds strategy based on tumor-specific infectivity of a replication-competent adenovirus with no E1 manipulation. The engineering of a capsid-coding region often disturbs viral production and replication by impaired viral assembly and maturation, possibly due to the conformational change of the fiber knob.15 A library approach with a replication-competent adenovirus may be highly useful to isolate a targeted oncolytic adenovirus, because the most efficient adenovirus should be selected from the library based on its high infectivity and replication capacity through the process of several rounds of virus amplification and spread through target cells.

We screened a peptide-display adenovirus library on a pancreatic cancer cell line to explore targeting ligands for pancreatic cancer because pancreatic cancer is one of the most intractable cancers, and new therapeutic approaches that can effectively target the spread of this cancer in vivo are urgently needed.15, 22, 23 In pancreatic cancer, a regional therapy is also particularly relevant, because locally advanced cases are surgically unresectable but can be accessible by ultrasound- or CT-guided percutaneous injection. In addition to locally advanced cases, distant metastasis at the liver and in the peritoneal cavity may be a clinical target of local oncolytic virus therapy. As a next step, a combination with other approaches such as immune therapies and systemic chemotherapies may contribute to mount a systemic antitumor effect against pancreatic cancer.

The intratumoral injection of AdΔCAR showed fewer EGFP-positive cells in the liver compared with Ad-EGFP. Although the liver infectivity of CAR-binding mutants is significantly reduced after intratumoral injection compared with the Ad-EGFP (Figure 3a), the lower ectopic liver transduction might be related to the inefficient proliferation of CAR-binding ablated viruses in the tumor. However, the intratumorally injected AdΔCAR-SYE rapidly proliferated and significantly inhibited the growth of an AsPC-1 tumor (Figure 5a) without an increase of the ectopic liver transduction compared with AdΔCAR (Figure 1). Therefore, both of the proliferation activity in the tumor and the in vivo hepatic infectivity of the virus may be related to ectopic liver transduction. In any case, as an adenovirus with a wild-type fiber causes ectopic liver transduction at a significantly high level following an intratumoral injection, the reduction of natural tropism and increased targetability are important even in an intratumoral injection strategy of an oncolytic adenovirus. As CAR-binding ablation alone does not strongly reduce the in vivo natural tropism of the adenovirus vector, the additional ablation of binding sites with integrin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans from the adenoviral capsid might be useful to further reduce naive tropism.24 Furthermore, it was recently reported that coagulation factor (F) X directly binds the hypervariable regions (HVR) of the hexon surface in an adenovirus, leading to liver infection.25 A targeted adenovirus constructed on a mutant HVR backbone to suppress a liver transduction might effectively allow for the development of vectors to specifically transduce certain tumors even through systemic administration.

A selected peptide showed pancreatic cancer-directed infection, because the enhancement of gene transduction by the selected adenovirus was observed in 4 of 5 pancreatic cancer cell lines (Figure 2b). The receptor may be shared by several pancreatic cancer cell lines, or the selected peptide motif binds to different receptors, which are expressed in each pancreatic cell line. Database searches (BLAST) revealed sequence homology of the selected peptide with a known human protein such as BH-protocadherin 7 (PCDH-7).26, 27 However, whether the receptors for PCDH-7 are actually responsible for the SYENFSA-mediated infection is not known. Identification of the receptors may be useful to understand the molecular characteristics of the target cells and can be applied for diagnosis, such as the detection of a relapse of the disease. Additional works, such as those with a proteomics approach, may enable identification of the corresponding receptors.

Although there was a possibility to isolate peptide sequences that can generally enhance gene transduction in many cells, a selected peptide showed cell type-directed infection, which was consistent with our previous results,15 suggesting that library screening based on the binding to target cells may enable identification of tumor-specific targeting ligands. In addition to the positive selection followed by a validation of the tumor cell specificity, negative selection can be incorporated in the early screening phase. We are developing two strategies for negative selection: one is the absorption of vectors, which show high infectivity for many cells, on the mixture of various normal cells before the screening on the target cells, and the other is in vivo screening of the library to specifically transduce tumors using animal models.

This library-based technology for a specific adenovirus vector selection may have broad implications for a variety of applications in medicine and medical sciences.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

In this study a human embryonic kidney cell line (293), pancreatic cancer cell lines (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, MIAPaCa-2, Panc-1 and PSN-1), prostate cancer cell line (PC3), glioma cell line (U138MG), and primary cultures of HUVEC and human pancreatic epithelial cells (HPE) were used. All the cancer cell lines except for PSN-1 were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA), and PSN-1 cell line was established in our laboratory.28 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS); pancreatic cancer cell lines and prostate cancer cell line were in an RPMI-1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) with 10% FBS; glioma cell line was in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (Sigma) with 10% FBS. Primary cultures of HUVEC and HPE (ACBRI 515) were purchased from Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co. (Osaka, Japan) and Cell Systems Corp. (Kirkland, WA, USA), respectively, and cultured according to the manufactures’ instructions. 293.HissFv.rec cells express an artificial receptor against six histidine (His) residues, containing an anti-His single chain antibody (sFv).29 The 293-38 is a high-efficiency virus-producing clone of 293 cells, and the 293-38 cells expressing an anti-His sFv stably (293-38.HissFv.rec) were generated by retrovirus-mediated transduction.15

Shuttle plasmids and recombinant adenovirus DNA

The fiber-modified adenoviral shuttle plasmid pBHIΔCAR includes a 76.1–100 map unit (mu) of the adenoviral genome with a single loxP site, a cytomegalovirus immediate early enhancer/promoter (CMV promoter), the EGFP gene and a SV40 poly(A) signal at the E3 region deleted (79.4–84.8 mu).29 The plasmid has two incompatible restriction enzyme sites in the HI-loop to display random peptides and includes 4-point mutations in the AB-loop of the fiber knob to abolish CAR binding, and six histidine residues were incorporated into the carboxy terminal of the fiber knob, so that the vector can be propagated in the 293 cells expressing an anti-His sFv. The pBHIΔCAR-SYE and pBHIΔCAR-IVR plasmids have TCGTATGAGAATTTTAGTGCG (SYENFSA) and ATTGTTCGTGGTCGGGTGTTT (IVRGRVF) sequences in the HI-loop of the shuttle plasmid, respectively. The pBHI-EGFP plasmid has a wild-type fiber and contains a CMV promoter-driven EGFP gene at the E3 region deleted. The adenoviral cosmid cAd-WT includes the 0–79.4 mu of the adenovirus genome containing a wild-type E1 region and a single loxP site at 79.4 mu. The cAd-WT was recombined with pBHIΔCAR to generate AdΔCAR-WT for preparation of adenoviral DNA tagged with a terminal protein (DNA-TPC), and was recombined with pBHIΔCAR-SYE and pBHIΔCAR-IVR plasmids to generate adenovirus vectors AdΔCAR-SYE and AdΔCAR-IVR, respectively, and was also recombined with pBHI-EGFP to generate Ad-EGFP. The replication-incompetent adenovirus vectors expressing EGFP (AdΔE1-EGFP) or no gene (AdΔE1) were prepared as described.30, 31 The adenovirus vectors were quantified by optical absorbance.32 The infectious units of the viruses were examined in 293-38.HissFv.rec cells, and the ratio of the viral particle to infectious unit for each virus was approximately 30.

Construction of a random peptide-display adenovirus library

A fiber-modified shuttle plasmid library was constructed as described.15 Briefly, the degenerate oligonucleotide 5′-AACGGTACACAGGAAACAGGAGACACAACTTTCGAA(NNK)7ACTAGTCCAAGTGCATACTCTATGTCATTTTCATGG-3′ (N=A, T, G or C, K=G or T) served as a template for PCR with the primers 5′-GAAACAGGAGACACAACTTTCGAA-3′ and 5′-CATAGAGTATGCACTTGGACTAGT-3′. The PCR product was ligated into the HI-loop portion of adenovirus shuttle plasmid pBHIΔCAR and transfected into Max Efficiency electrocompetent cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by electroporation. The fiber-modified shuttle plasmid library was recombined with equal moles of the left hand of the digested DNA-TPC by Cre recombinase (Clontech, Madison, WI, USA) in vitro to produce a full-length adenovirus genomic DNA library. Then, to generate replication-competent peptide-display adenovirus libraries, recombined adenoviral DNA was transfected by the lipofection method (Lipofectamine Reagent; Invitrogen) into 293-38.HissFv.rec cells. When the cells showed an expansion of the cytopathic effect, the first generation of the adenovirus library was harvested. The 293-38.HissFv.rec cells were infected with the CVL again, and the second generation of the library was harvested. The library was estimated to display more than 1 × 104 peptides on the fiber per 60-mm dish.15 As the library used in the screening was collected from twenty 60-mm dishes, the complexity of the peptide sequences displayed in the library was estimated to be approximately at a 2 × 105 level, and the final concentration of the virus library was prepared as 1 × 109 PFU ml−1.

Screening of a random peptide-display adenovirus library

The 2 × 106 of AsPC-1 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes. One day later the cells were infected with a peptide-display adenovirus library at MOI of 1, and 2 h later the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline. In the initial phase of the screening, many low-affinity or nonspecific viruses might bind and internalize into the AsPC-1 cells; however, the use of a replication-competent type of adenovirus could allow for the rapid spreading of the most efficient viruses present in the library, leading to an effective enrichment of such viruses. After 5–7 days following the infection, the replicated adenoviruses were harvested from the cells, and the CVL was reapplied to the target cells at MOI of less than 1. The process was repeated three times.

PCR and sequencing of adenovirus library clones

DNA was extracted from the CVL of the third selection round and then served as a template for a PCR with the primers containing upstream and downstream sequences of the HI-loop: 5′-GAAACAGGAGACACAACTTTCGAA-3′ and 5′-CATAGAGTATGCACTTGGACTAGT-3′. PCR products were cloned into the pBHIΔCAR plasmid. Randomly assigned clones were sequenced using the primer 5′-GGAGATCTTACTGAAGGCACAGCC-3′.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The 1 × 104 of cells were seeded per well in a 96-well plate, and 24 h later the cells were infected with adenoviruses at various MOI. Viable cells were assessed by a colorimetric cell viability assay using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (Tetracolor One; Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) 5 days after the infection. The absorbance was determined by spectrophotometry using a wavelength of 450 nm with 595 nm as a reference.

Subcutaneous tumor model

Female BALB/c nude mice (4- to 5-week old) were purchased from Charles River Japan Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan), and were housed under sterilized conditions. Animal studies were carried out according to the Guideline for Animal Experiments of the National Cancer Center Research Institute and approved by the Institutional Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation. AsPC-1 (5 × 106) and PC3 (1 × 107) cells were subcutaneously injected into the leg of mice. When tumor mass was established (∼0.6 cm in a diameter), 50 μl of a viral solution (0.5–5 × 108 PFU) was injected into the tumor with a 29-gauge hypodermic needle, and the animals were observed for tumor growth. The short (r) and long (l) diameters of the tumors were measured and the tumor volume of each was calculated as r2 × l/2.

Immunohistochemistry

The expression of adenovirus hexon protein in the virus-injected tumors was assessed by an immunohistochemistry using streptoavidin—biotin–peroxidase complex techniques (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). Cryostat tissue sections (4 μm) fixed in cold acetone for 5 min were mounted on glass slides. After blocking with normal goat serum, the sections were stained with goat anti-adenovirus hexon antibody (AB1056; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). Parallel negative controls without primary antibodies were examined in all cases. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Detection of adenovirus DNA from the tumors and normal organs

The subcutaneous tumors and normal organs such as the liver, spleen and lung were collected 2 and 6 days after the intratumoral injection of an adenovirus solution (2.5 × 108 PFU), and DNA was extracted from the tumors and organs using Sepagene (Sankojunyaku, Tokyo, Japan). PCR amplification was carried out using 50 ng of DNA in a 50 μl PCR mixture with the CAR-binding region upstream (5′-GATTCAAACAAGGCTATGGT-3′) and downstream (5′-AAGATGAGCACTTTGAACTG-3′) primers. In total, 30 cycles of the PCR were carried out at 95 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 2 min. Then PCR products were fractionated on a 2.0 % of agarose gel.

Statistical analysis

Comparative analysis of EGFP-positive cell number and frequency, in vitro cell proliferation and subcutaneous tumor growth was performed by the Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P-value was <0.05.

References

Lin E, Nemunaitis J . Oncolytic viral therapies. Cancer Gene Ther 2004; 11: 643–664.

Rein DT, Breidenbach M, Curiel DT . Current developments in adenovirus-based cancer gene therapy. Future Oncol 2006; 2: 137–143.

Young LS, Searle PF, Onion D, Mautner V . Viral gene therapy strategies: from basic science to clinical application. J Pathol 2006; 208: 299–318.

Shinoura N, Yoshida Y, Tsunoda R, Ohashi M, Zhang W, Asai A et al. Highly augmented cytopathic effect of a fiber-mutant E1B-defective adenovirus for gene therapy of gliomas. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3411–3416.

Hemminki A, Dmitriev I, Liu B, Desmond RA, Alemany R, Curiel DT . Targeting oncolytic adenoviral agents to the epidermal growth factor pathway with a secretory fusion molecule. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 6377–6381.

Bauerschmitz GJ, Lam JT, Kanerva A, Suzuki K, Nettelbeck DM, Dmitriev I et al. Treatment of ovarian cancer with a tropism modified oncolytic adenovirus. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 1266–1270.

Hedley SJ, Chen J, Mountz JD, Li J, Curiel DT, Korokhov N et al. Targeted and shielded adenovectors for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2006; 55: 1412–1419.

van Beusechem VW, Mastenbroek DC, van den Doel PB, Lamfers ML, Grill J, Wurdlinger T et al. Conditionally replicative adenovirus expressing a targeting adapter molecule exhibits enhanced oncolytic potency on CAR-deficient tumors. Gene Therapy 2003; 10: 1982–1991.

Hemminki A, Alvarez RD . Adenoviruses in oncology: a viable option? BioDrugs 2002; 16: 77–87.

Ranki T, Kanerva A, Ristimaki A, Hakkarainen T, Sarkioja M, Kanganiemi L et al. A heparan sulfate-targeted conditionally replicative adenovirus, Ad5.pk7-Delta24, for the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Gene Therapy 2007; 14: 58–67.

Nicklin SA, Von Seggern DJ, Work LM, Pek DC, Dominiczak AF, Nemerow GR et al. Ablating adenovirus type 5 fiber-CAR binding and HI loop insertion of the SIGYPLP peptide generate an endothelial cell-selective adenovirus. Mol Ther 2001; 4: 534–542.

Joung I, Harber G, Gerecke KM, Carroll SL, Collawn JF, Engler JA . Improved gene delivery into neuroglial cells using a fiber-modified adenovirus vector. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 328: 1182–1187.

Nicklin SA, White SJ, Nicol CG, Von Seggern DJ, Baker AH . In vitro and in vivo characterisation of endothelial cell selective adenoviral vectors. J Gene Med 2004; 6: 300–308.

Muller OJ, Kaul F, Weitzman MD, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Kleinschmidt JA et al. Random peptide libraries displayed on adeno-associated virus to select for targeted gene therapy vectors. Nat Biotechnol 2003; 21: 1040–1046.

Miura Y, Yoshida K, Nishimoto T, Hatanaka K, Ohnami S, Asaka M et al. Direct selection of targeted adenovirus vectors by random peptide display on the fiber knob. Gene Therapy 2007; 14: 1448–1460.

Nicklin SA, Wu E, Nemerow GR, Baker AH . The influence of adenovirus fiber structure and function on vector development for gene therapy. Mol Ther 2005; 12: 384–393.

Einfeld DA, Schroeder R, Roelvink PW, Lizonova A, King CR, Kovesdi I et al. Reducing the native tropism of adenovirus vectors requires removal of both CAR and integrin interactions. J Virol 2001; 75: 11284–11291.

Brand K, Klocke R, Possling A, Paul D, Strauss M . Induction of apoptosis and G2/M arrest by infection with replication-deficient adenovirus at high multiplicity of infection. Gene Therapy 1999; 6: 1054–1063.

Bruder JT, Kovesdi I . Adenovirus infection stimulates the Raf/MAPK signaling pathway and induces interleukin-8 expression. J Virol 1997; 71: 398–404.

Alemany R, Balague C, Curiel DT . Replicative adenoviruses for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol 2000; 18: 723–727.

Suzuki K, Fueyo J, Krasnykh V, Reynolds PN, Curiel DT, Alemany R . A conditionally replicative adenovirus with enhanced infectivity shows improved oncolytic potency. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 120–126.

Yoshida T, Ohnami S, Aoki K . Development of gene therapy to target pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 283–289.

Safioleas MC, Moulakakis KG . Pancreatic cancer today. Hepatogastroenterology 2004; 51: 862–868.

Mizuguchi H, Koizumi N, Hosono T, Utoguchi N, Watanabe Y, Kay MA et al. A simplified system for constructing recombinant adenoviral vectors containing heterologous peptides in the HI loop of their fiber knob. Gene Therapy 2001; 8: 730–735.

Waddington SN, McVey JH, Bhella D, Parker AL, Atoda H, Pink R et al. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell 2008; 132: 397–409.

Yoshida K, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Seki N, Sasaki M, Sugano S . Cloning, expression analysis, and chromosomal localization of BH-protocadherin (PCDH7), a novel member of the cadherin superfamily. Genomics 1998; 49: 458–461.

Yoshida K, Watanabe M, Kato H, Dutta A, Sugano S . BH-protocadherin-c, a member of the cadherin superfamily, interacts with protein phosphatase 1 alpha through its intracellular domain. FEBS Lett 1999; 460: 93–98.

Yamada H, Yoshida T, Sakamoto H, Terada M, Sugimura T . Establishment of a human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line (PSN-1) with amplifications of both c-myc and activated c-Ki-ras by a point mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1986; 140: 167–173.

Douglas JT, Miller CR, Kim M, Dmitriev I, Mikheeva G, Krasnykh V et al. A system for the propagation of adenoviral vectors with genetically modified receptor specificities. Nat Biotechnol 1999; 17: 470–475.

Aoki K, Barker C, Danthinne X, Imperiale MJ, Nabel GJ . Efficient generation of recombinant adenoviral vectors by Cre-lox recombination in vitro. Mol Med 1999; 5: 224–231.

Ohashi M, Yoshida K, Kushida M, Miura Y, Ohnami S, Ikarashi Y et al. Adenovirus-mediated interferon alpha gene transfer induces regional direct cytotoxicity and possible systemic immunity against pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2005; 93: 441–449.

Mittereder N, March KL, Trapnell BC . Evaluation of the concentration and bioactivity of adenovirus vectors for gene therapy. J Virol 1996; 70: 7498–7509.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for the 3rd Term Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, grants-in-aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and by the program for promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NiBio). T Nishimoto, Y Miura and H Hara are awardees of a Research Resident Fellowship from the Foundation (Japan) for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Gene Therapy website (http://www.nature.com/gt)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishimoto, T., Yoshida, K., Miura, Y. et al. Oncolytic virus therapy for pancreatic cancer using the adenovirus library displaying random peptides on the fiber knob. Gene Ther 16, 669–680 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2009.1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2009.1