Abstract

Purpose: The clinical introduction of first trimester aneuploidy screening uniquely challenges the informed consent process for both patients and providers. This study investigated key aspects of the decision-making process for this new form of prenatal genetic screening.

Methods: Qualitative data were collected by nine focus groups that comprised women of different reproductive histories (N = 46 participants). Discussions explored themes regarding patient decision making for first trimester aneuploidy screening. Sessions were audio recorded, transcribed, coded, and analyzed to identify themes.

Results: Multiple levels of uncertainty characterize the decision-making process for first trimester aneuploidy screening. Baseline levels of uncertainty existed for participants in the context of an early pregnancy and the debate about the benefit of fetal genetic testing in general. Additional sources of uncertainty during the decision-making process were generated from weighing the advantages and disadvantages of initiating screening in the first trimester as opposed to waiting until the second. Questions of the quality and quantity of information and the perceived benefit of earlier access to fetal information were leading themes. Barriers to access prenatal care in early pregnancy presented participants with additional concerns about the ability to make informed decisions about prenatal genetic testing.

Conclusions: The option of the first trimester aneuploidy screening test in early pregnancy generates decision-making uncertainty that can interfere with the informed consent process. Mechanisms must be developed to facilitate informed decision making for this new form of prenatal genetic screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Two changes have taken place in the practice of obstetrics that affect every pregnant woman in the United States. These changes, one in clinical practice guidelines and the other in genetic screening technology, were put into place to enhance pregnant women's access to fetal genetic information and expand the range of choices about pregnancy. Although intended to improve the quality of antepartum care, these tandem events introduce new challenges for informed consent and decision making. In doing so, they provoke salient questions about how patients provide informed consent for fetal genetic testing and how clinicians facilitate patients' informed decision making under this new paradigm of prenatal care.

One of these important changes took place when the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists updated their practice recommendations regarding prenatal genetic testing. This new statement recommended the universal offering of fetal aneuploidy screening and testing for all patients.1 Before this new recommendation, aneuploidy screens were offered predominantly to patients of advanced maternal age, i.e., women aged 35 years or older at the time of delivery. This update reflected the growing appreciation that all women are at risk for carrying a fetus with this kind of chromosomal abnormality.1 Although the risk of fetal aneuploidy does increase with a woman's age, the former practice was based more on a statistical cutoff value that weighed the risk of a woman giving birth to a child with Down syndrome against the chance of iatrogenic miscarriage from invasive diagnostic procedures.1 The modified recommendation places greater emphasis on patients' personal preferences about pregnancy, disability, parenthood, and abortion than statistically derived comparisons. By expanding the potential testing pool, this new clinical recommendation will increase the number of patients who must be prepared to make informed decisions about aneuploidy screening tools.

Another notable event was the clinical introduction of a new way to perform aneuploidy screening. Until recently, the Triple Screen and the Quadruple Screen were the primary tools for prenatal aneuploidy screening.2–4 One of the limitations of these conventional screening procedures is their timing, as they are not be performed until after the 15th week of pregnancy. Thus, choices about the pregnancy after confirmatory diagnostic testing cannot be made until well into the second trimester, a time when the choice to continue or terminate the pregnancy has very different implications.5 First trimester aneuploidy screening is a new approach consisting of risk calculation based on measurements of maternal serum markers and fetal nuchal translucency. This new tool confers similar fetal genetic risk information regarding Down syndrome as the Quadruple Screen but is performed as early as 11 weeks' gestation.6–8 Timed 1 month earlier than its second trimester counterparts, this new screening modality gives patients a wider range of options during the course of their prenatal care, including the opportunity to undergo immediate diagnostic procedures.

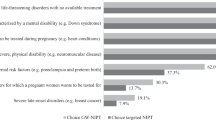

These events are significant because of the 2-fold impact they carry for informed consent. Patient education and informed decision making are two core components of informed consent. By expanding the indications for fetal aneuploidy testing to all pregnant patients, obstetric providers must now meet the practical challenges of facilitating patient education and informed decision making for larger number of pregnant women. At the same time, the advent of first trimester aneuploidy screening expands the panel of prenatal testing options, requiring additional time and resources to prepare patients to make informed decisions whether to undergo or defer this opportunity (Figure 1). However, the preexisting shortage of certified genetic counselors and health care providers with specific training in genetics illuminates the magnitude of the task at hand.9 At the same time, there is a body of literature outlining the numerous barriers to informed consent for prenatal genetic testing that have existed even before the clinical introduction of this new form of aneuploidy screening.10–15 The current situation raises timely and important questions about health care professionals' ability to meet the informed decision-making needs of pregnant patients as they consider their current range of testing options.

An additional challenge for health care professionals is ensuring that patients understand the unique test characteristics of first trimester aneuploidy screening and how it differs from its conventional precursors. First, this new aneuploidy screen combines two procedures, a blood draw and an ultrasound, into a single risk assessment.6,7 In contrast, the Triple and Quadruple Screens are a one-step procedure that calculates risk based on measurements from a single blood draw.8 As part of the informed consent process for first trimester screening, patients must comprehend how and why these two separate testing procedures are performed and how to individualize fetal risk for Down syndrome from them. Additionally, they must also comprehend their other available testing options, including the possibility of downstream tests and procedures based on the first screen result. For example, first trimester screening may either be used alone or, more commonly, in conjunction with second trimester maternal serum measurements to increase the detection rate of aneuploidy.16,17 Patients must also comprehend the potential for combined protocols, specifically when they are used and what the final result means in terms of the health of the developing fetus. In addition, they must be aware of their first trimester diagnostic testing options in the case of an abnormal screen result.1 Thus, the introduction of first trimester aneuploidy screening undoubtably expands the educational and decision-making needs that must be met by obstetric providers in the informed consent process.

Prenatal screening without informed consent puts patients at risk for engaging in procedures and choices for which they were unprepared to make about the pregnancy, such as the decision for further genetic testing or considering the option of pregnancy termination. Given the importance of informed consent for genetic testing and the challenges taking shape in the current setting of prenatal medicine, we designed this study to collect information about the process of decision making for first trimester aneuploidy screening. These data are critical to determining patients' informational needs to guide decision making regarding use of this new form of prenatal genetic testing. In turn, these findings can be used to develop targeted educational interventions to meet these needs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Focus groups were conducted and analyzed to explore women's decision making for first trimester aneuploidy screening. Participants were recruited from the Cleveland Clinic outpatient obstetric clinics. Inclusion criteria for participation included women between the ages of 18 and 45 years with a current or past history of pregnancy. For the purpose of recruitment, current pregnancy included women at any trimester of pregnancy. A past history of pregnancy included those women who had delivered a previable fetus or viable neonate (whether a live birth or intrauterine fetal demise), experienced a miscarriage, or undergone pregnancy termination. Exclusion criteria included women younger than 18 years, inability to provide consent for research participation, prior participation in this study, or inability to speak or read English.

Study personnel recruited participants by approaching pregnant patients in the waiting rooms of eight outpatient obstetric clinics. Those who expressed interest in participating in the study were asked to provide contact information for focus group scheduling. Participants were also asked to self-report their reproductive history by responding to a basic set of questions about their current and past pregnancies. Recruitment also took place using fliers posted at each clinic. Interested patients were instructed to contact study personnel by telephone for additional information and to provide contact and basic reproductive history information for scheduling of the focus groups.

A follow-up phone call was placed to schedule participants into specific focus groups depending on their reproductive history and time availability. To explore different stages of the decision-making process for aneuploidy screening, participants were stratified based on their reproductive history and were assigned to one of three subgroups to reflect these obstetric experiences: (1) women who were currently pregnant with their first pregnancy (to capture the framework of the initial decision-making process), (2) women who were currently pregnant and had been pregnant in the past (to capture varied educational needs concerning experience with pregnancy and prenatal genetic testing), and (3) women who were not pregnant but had been pregnant in the past (to capture the reflective insight of undergoing testing on the experience of decision making during pregnancy). Sampling was performed to conduct a minimum of nine focus groups, with three focus groups per obstetric subgroup. Recruitment and data collection were continued until content saturation was received, and participants were broadly distributed across the three obstetric groups.

Four to six participants were included in each focus group, and a total of nine focus groups were conducted with multiple sessions per subgroup. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of the session. Before the focus group discussion, all participants were asked to complete a brief questionnaire. This instrument contained multiple-choice questions to collect information on participant demographics, knowledge of Down syndrome and aneuploidy screening tests, and experience with genetic testing during this or previous pregnancies. Items for this instrument were developed based on current professional medical organizations' guidelines for aneuploidy screening.1

All focus groups were facilitated with a moderator guide consisting of a series of open-ended questions. Each discussion was guided by a line of inquiry exploring experiences, attitudes, and perceptions about pregnancy and genetic testing, with a specific group of questions that addressed first trimester aneuploidy screening. Additional topic areas included the role of a screen-positive result and the risks and benefits of follow-up diagnostic testing and the decision-making process. As this is a new method of prenatal aneuploidy screening, two steps were taken to develop a consistent level of knowledge among participants. First, the moderator introduced the topic of first trimester aneuploidy screening to explore initial reactions and responses to this new test. Because knowledge of a series of medical terms was required for this discussion (i.e., aneuploidy, nuchal translucency, and chorionic villus sampling) a 5-minute informational video was shown in the beginning stages of each focus group, which provided a basic outline of first trimester aneuploidy screening and follow-up testing options. This video was developed by the study investigators and presented the customary information domains of informed consent for aneuploidy screening as based on recommendations in the literature, including the indications, risks, benefits, follow-up diagnostic procedures, and alternatives of first trimester aneuploidy screening. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions specific to first trimester aneuploidy screening before continuing with the discussion. A content expert was present during the focus group sessions to answer these questions. Focus group sessions last approximately 90 minutes and were digitally audio recorded and transcribed. All participants received compensation for their participation.

A combination of grounded theory and analytic induction methods was used to identify patterns and major themes in the focus group narratives.18 Two members of the research team used a sample of transcripts to create a coding scheme to categorize the text into major domains, subdomains, and subcategories. Consensus for the resulting coding scheme was achieved among the research team through research meetings. Two members of the research team then conducted independent analysis of all transcripts using NVivo8, followed by review of their respective codes and resolution of discrepancies through consensus. The research team then used inductive analysis to generate interpretations of the focus group narratives from the coded transcripts.

Data analysis from the participant questionnaire was conducted using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Frequency data were generated for participant demographics, knowledge, and experience of aneuploidy screening.

RESULTS

A total of 46 patients participated in nine focus groups (Table 1). Most participants were 26–30 years of age (32.6%) or older than 35 years (28.0%), white (72.0%) or African American (22.0%), and had either a college (52.0%) or graduate (30.0%) degree. More than half (54.0%) were currently pregnant, and of those, 54.0% were pregnant for the first time (Table 2).

Sixty-three percent reported some basic knowledge of first trimester aneuploidy screening, and 35.0% reported that they had already undergone first trimester aneuploidy screening (Table 3). A greater percentage of participants reported knowledge of (82.6%) and experience with (50.0%) the Quadruple Screen. Most were familiar with amniocentesis (89.0%) and fewer with chronic villus sampling (42.5%). Reported experience with one or both of these diagnostic tests was uncommon, as only 13.0% of participants reported having undergone amniocentesis and 4.5% chronic villus sampling.

Qualitative analysis: Themes and domains

The focus group narratives illustrated a recurrent theme of uncertainty surrounding the first trimester and the decision for aneuploidy screening in general. One set of themes pertained to uncertainty at baseline, including emotional responses to a new pregnancy, candidates for aneuploidy screening, and the advantages and disadvantages of aneuploidy screening at any time in the pregnancy. Another set of themes emerged regarding first trimester aneuploidy screening, specifically concerning the benefits and drawbacks of initiating fetal genetic inquiries in the early weeks of pregnancy compared with deferring this until the second trimester. Discussions revealed that uncertainties regarding first trimester aneuploidy screening were layered on to more general baseline concerns, resulting in multifaceted sources of uncertainty that characterized the decision-making process for this new form of aneuploidy screening.

The first trimester of pregnancy and the stage of decision making

Participants reported that the first trimester is an emotionally and physically tumultuous time. Participants described a broad spectrum of emotions and uncertainty at a baseline in both their physical and psychological reactions to pregnancy before contemplating any available testing options. These concerns composed the bulk of decision-making activities in the first trimester.

The range of emotional responses to a new pregnancy was associated with several factors. One factor pertained to the planned or unplanned nature of the pregnancy. Several participants commented that the pregnancy was unanticipated, and their reactions to their situation were mixed. Participants captured this sentiment with “This one was a shocker to me,” “I had a lot of mixed emotions,” and “When I found out I was pregnant I went through every emotion in the spectrum.” Even in the context of a desired and planned pregnancy, participants reported experiencing a wide range of emotions during the first trimester. A participant described her own experiences as, “I think I have a lot of mixed emotions … I was excited … I was nervous that something would go wrong.”

Issues of fertility were another contributor to the context of the first trimester. In particular, participants who experienced delayed times to pregnancy or assisted reproductive technologies described initial anxiety, disbelief, and emotional distancing from the pregnancy that was strongest in the first trimester with comments such as “My husband and I tried getting pregnant for five years and we went through all the different treatments and everything … So when it finally happened it was shock. It was disbelief, um, I didn't even believe it for like four months. It just didn't set in.” For these participants, emphasis during this time was more on disbelief and then celebration of conception rather than their genetic testing options.

The physical events of the first trimester were also a prominent theme. Participants verbalized their comprehension that miscarriage most often occurs in the first weeks of pregnancy, either from their own personal experiences or from the experiences of friends and family. Tangible concerns about pregnancy loss arising from vaginal bleeding or the findings of an early ultrasound colored the initial experiences and attachment to the pregnancy. These concerns were also expressed by those women who had experienced miscarriage, fetal loss, or neonatal death in a previous pregnancy. As one participant shared, “I definitely had some more trepidation because I did have a miscarriage. So, I was very nervous during those beginning weeks and um, it was hard for me to be happy ….”

Baseline uncertainty Part I: Who is at risk?

There was uncertainty and indecision among the groups about which patients were at increased risk for having a fetus with Down syndrome and who should be recommended for aneuploidy screening. In general, participants were not familiar with the current scientific evidence that all women are at risk for fetal aneuploidy. There was a similar lack of awareness about current recommendations of prenatal screening for all pregnant patients. Most participants discussed advanced maternal age as the primary indication for testing and stated that younger women would not be indicated for or have any need to undergo aneuploidy screening. One participant captured this concept by stating “I didn't see myself as being high risk because I am only twenty-eight and my view of having that first trimester screening is for older women that are approaching thirty-five or over thirty-five. I didn't think that it would be for me even if it was offered.” Another participant who met the criteria for advanced maternal age reflected on another type of misperception about the use of these tests during prenatal care. “I think my doctor had mentioned it, but also because I was over thirty-five, I knew I would—I thought I would be getting an amniocentesis. So, I wasn't really too mindful of the first trimester screening.”

Baseline uncertainty Part 2: Benefits and risks of aneuploidy screening

Participants articulated a range of benefits of aneuploidy screening, described in terms of the ability to prepare for the birth of a child with disabilities or to decrease anxiety. “I always believe in trying to get as much information as you can … be well informed, and be able to make the decisions. So part of me early on was leaning definitely toward [testing]. Well, let's get the test because if something is wrong we will at least be able to study up and be knowledgeable and be prepared.”

Participants outlined the risks of aneuploidy screening and follow-up testing. Specifically, participants discussed the risk of iatrogenic miscarriage and the impact a screen-positive result would have in the decision to go ahead with follow-up testing. Although participants recognized the significance of the physical risks associated with screening and testing, they were much more vocal about the emotional sequelae associated with aneuploidy screening and the dominant role this played on the decision-making process. Specifically, concerns about emotional stress and anxiety resonated throughout discussions of aneuploidy screening. “Having already lost one pregnancy I knew that if we got either a false positive or negative results back it would only add to the stress of the pregnancy and it wasn't going to change the outcome... We opted to just alleviate that additional stress that could have taken place.”

Despite the fact that participants could readily articulate the benefits and risks of aneuploidy screening, they seemed very conflicted over which factor might outweigh the other. Participants expressed uncertainty about the best course of action, both in theory and in the context of their own pregnancy. As expressed by one participant, “You wouldn't want to spend nine months worrying. Then on the other hand, you might want to know because you might want to be prepared. So it [the decision for aneuploidy screening] would be hard. That would be really hard and I'm glad I'm here and I'm thinking about all this because it really poses a lot of questions. You know, what would I really do?”

Is earlier better? Considering the timing of first trimester screening

Indecision and uncertainty about prenatal testing carried over into discussions specific to first trimester aneuploidy screening. Some participants viewed testing earlier in the pregnancy as a better alternative than waiting until the second trimester. One participant expressed her beliefs as, “I don't feel right about aborting a baby that is so far along. If we are going to make that decision I would rather make it at 13 weeks than make it at 20 weeks or you know, what have you. So we went with the earlier test.” Those who voiced a preference for first trimester testing also cast their perspectives in terms of the psychological benefits of earlier testing. “It would be a harder decision to make, as a woman, to decide to continue … with the pregnancy if you knew for certain very early on that there could be something wrong.” For these women, earlier information provided a longer period of reassurance and freedom from anxiety about the health of the fetus or choices to face during the pregnancy. Some participants raised the value of decision making about fetal genetic testing before the outward physical manifestations of pregnancy have become apparent to family and friends. “My thought on the first trimester screening is that … you have a lot more choices as an individual being so early on at week 11 or 12. Because if you so choose, pretty much no one can know you are pregnant and um, so that is a good thing … that would be something that at least could be a very private decision.”

For most participants, the advantages of first over second trimester aneuploidy screening were less definitive. Indecision predominantly revolved around whether earlier testing would increase or decrease stress and anxiety about the pregnancy. For a majority of the participants, earlier testing introduced a component of anxiety into the early pregnancy that lingered until delivery. One participant captured a recurrent theme among the group by commenting, “I am kind of one of those people would kind of rather find out later. I didn't want to have to spend the next, you know, six months or so, you know, stewing and worrying about that because that is not healthy for anybody either,” while another added, “If they [her children] weren't born healthy, would I have wanted to know so that I could start collecting resources and know what to do? I weighed that between spending nine months worrying about it and the false positives … I'd rather know later than … trying to live that nine months. To me that [information from first trimester screening] would just been too much of a burden at that point in time.”

Decision-making about the timing of testing seemed to be less influenced by physical considerations of pregnancy termination. None of the participants addressed the fact that earlier diagnosis would be associated with a decrease in procedure-related risks of termination or emotional sequelae in the first trimester as opposed to the second.

Informational mismatch and decision making for first trimester screening

Participants discussed preferences about the kind of information that they believe should be presented during discussions about first trimester aneuploidy screening. As in the case of conventional forms of aneuploidy screening, the standard informational domains of indications, risks, benefits, and alternatives were a part of the decision-making process. A critical aspect of these discussions was the consideration of disability and pregnancy termination. Participants expressed the need for their obstetric providers to “be upfront,” “not assume anything,” and openly broach patient values and preferences about continuing or terminating a pregnancy with an affected fetus before going ahead with first trimester screening. “I just want to make sure when you choose the test, to be aware of what's gonna happen. And then also so if you choose this test–if it's positive– are you going to consider to keep the baby or are you going to give up? So I think parents should be aware about what's going to happen after this test. So I think that's also has to be informed.”

Participants discussed their experiences specific to the decision-making process, namely the ability to access and discuss the consequences of initiating first trimester aneuploidy screening. Information about possible avenues following screening was so highly valued that, in some instances, discussion of downstream options took priority over the standard information domains for aneuploidy screening. “It's [the choice to continue or terminate the pregnancy] an important ethical part of the whole decision about whether or not to take any of these tests.” In some cases, participants reflected on the difficulty of eliciting this type of information during discussions about testing. For many, it seemed that their health care provider placed more emphasis on the standard information domains of aneuploidy screening and less on the topics that were their key decision-making factors for this test.

Shifting decision making to the first trimester: Access to the right kind of information at the right time

Participants articulated two leading aspects of the decision-making process for first trimester aneuploidy screening that pose challenges within the current practice patterns of prenatal care. First, on a practical level, participants voiced concern about the narrow window of time in which to make an informed decision about first trimester aneuploidy screening. All participants stated that they wanted access to information about the screen as early as possible. However, for many patients, the timing of access was a challenge. One participant reflected on her recent experiences, noting that the initial obstetric visit was not until the later half of the first trimester. “My obstetrician doesn't even want to see us until we're eight weeks pregnant so that doesn't leave a whole lot more time in your first [trimester]. So, I'd like to hear about it at my first visit if that were the case so that I would know that was an option to mull over before you know, before that time came up.” Participants did not feel that they had sufficient time to learn about Down syndrome, screening and testing options, and how to interpret the different test results with the limited time between the initial prenatal visit and the timing of first trimester aneuploidy screening. As stated by one participant, “You almost would have had to gone in [for the initial obstetric visit] knowing that it is an option.” In addition, comments addressed the concern they did not have adequate time in this narrow window to resolve any of their own baseline uncertainty regarding personal values of abortion and disability in addition to the decision and whether to engage in any form of genetic testing.

Even if patients had earlier access to prenatal care, they found the first prenatal visit ripe for information overload. “That initial prenatal appointment is overwhelming. There is a lot of information presented to you and you don't necessarily remember everything and you're excited and you forget what questions you do have.” Regardless of reproductive history, the first obstetric visit was perceived as an information-rich time. Participants discussed that this visit is primarily an opportunity to obtain fundamental information about pregnancy and routine milestones of prenatal care. Information pertaining to early genetic testing was often a secondary concern during this visit, unless the pregnant woman had a medical or reproductive history for which lead her to inquire about such tests. For most participants, these first weeks were the “honeymoon” period of a pregnancy, when the thoughts about children and the transition to motherhood took precedence. For others, this was a time when the concern about the threat of miscarriage was real. In addition, there was a subset who was taken aback by the nature of this discussion at the intial prenatal visit. “It was one of those early meetings where you go in and suddenly he [the obstetrician] was just kind of giving me the gamut of possibilities.”

The timing of first trimester screening was another important consideration in the decision-making process and the ability to acquire necessary informational factors. Given the specific timing of the test and gestational age at the initial prenatal visit, conversations about fetal genetic testing, disability, and abortion were topics that had to be discussed at the first prenatal visit. Participants noted that these are some of the most challenging topics to broach and explore in any physician-patient relationship, both in a new and existing relationship. Participants described the first prenatal appointment as a difficult and often awkward time to initiate, discuss, or be receptive to conversations about these deeply personal values. The challenges of these discussions were most pronounced when the patient and physician met for the first time at the beginning of the pregnancy. However, participants voiced the importance of these discussions even in the early weeks of the pregnancy.

DISCUSSION

Although first trimester aneuploidy screening provides women with the opportunity to make decisions at an earlier stage of pregnancy, it also introduces a set of unique challenges for both patients and providers. These challenges, in turn, carry the potential to interfere with informed decision making and meaningful informed consent.

One important factor is the unique decision-making time frame introduced by first trimester aneuploidy screening. The timing of this new screen shifts decision making about prenatal genetic testing from the second trimester into the first, thus changing the context of these extremely important decisions. This shift is significant because the first trimester is a distinct period in pregnancy characterized by a specific set of changes for the pregnant woman. It is common for a woman at this time to be under physical strains from nausea, vomiting, and fatigue.19 Studies have shown that emotional stress and anxiety peak during this time.20,21 Common stressors also include the potential for miscarriage, knowledge of an unplanned pregnancy, or anxiety in reaction to a history of miscarriage, fetal loss, or infertility.

Our findings illustrate several important implications of shifting decision making to the first trimester. Data from the focus groups illustrate that uncertainty characterizes the decision-making context for first trimester aneuploidy screening. One source of uncertainty arises from the baseline context of the first weeks of a new pregnancy. Women in our study expressed a wide range of emotions about the circumstances of this period. Although some women described happiness or excitement about the new pregnancy, comments were overarchingly characterized by worry, anxiety, and uncertainty. Even in the context of a planned, desired pregnancy, women recalled the uneasiness of this time in terms of planning for their impending role of mother and the health of the fetus. As a significant number of pregnancies each year continue to be unplanned,22 it is not surprising that some participants also described this as an emotional time during which they came to terms with an unplanned pregnancy and faced considerations about whether to continue or terminate in these beginning weeks. These findings speak to the level of baseline decisional uncertainty regarding a new pregnancy that coincides with the testing window for first trimester screening.

Uncertainty also is generated from decision making specific to aneuploidy screening. Our study shows that, during the first trimester of pregnancy, women struggled with the decision to undergo any form of aneuploidy screening, whether in the first or second trimester. As this is a period of uncertainty about the outcome of the pregnancy itself, participants expressed their indecision about whether the benefits of screening at this time outweigh its burdens and risks. Another stressor arose from the choice to initiate screening in the first trimester of pregnancy or to wait until the second. The choice to undergo testing at this stage of the pregnancy was neither clear cut nor was the notion that “earlier is better.” For some, earlier testing introduced a level of worry that, if the Quadruple Screen had been selected, would have been deferred until later and, thus, had an appreciably different effect on the experience of pregnancy.

Shifting aneuploidy screening decision making into the first trimester entails another consideration for informed consent. Most pregnant women present for their initial prenatal visit between 8 and 12 weeks of pregnancy. For our participants, this time frame was a function of one's ability to access a health care provider after learning about a new pregnancy or the practice patterns of the chosen obstetric practitioner. Because of the close proximity of the initiation of prenatal care to the latest possible time to undergo first trimester aneuploidy screening, the bulk of education and decision making must take place during or within the initial clinical visit. This is an important contrast to the Quadruple Screen in which patient education and decision making take place over the course of one to two additional prenatal encounters. Furthermore, this is an information-rich visit with the potential for “information overload” as patients must also learn about and make choices regarding a variety of other tests customarily performed in these early weeks of pregnancy. As voiced by the participants, this decision-making context strains the educational and cognitive processes needed to make an informed decision about first trimester screening before its window of opportunity has passed.

What is significant about these findings is that they have the potential to interfere with the core processes of informed decision making, raising questions about the integrity and effectiveness of informed consent for first trimester aneuploidy screening. Women considering any form of prenatal genetic testing face a steep learning curve about genetic disease, testing modalities, and concepts of risk. As choices about prenatal genetic testing involve profoundly personal values, patients must also have the opportunity to integrate this information with their beliefs about motherhood, disability, and abortion before proceeding with testing. However, these cognitive processes can all be negatively affected by the common stressors of the first trimester of pregnancy. Specifically, uncertainty and anxiety can interfere with the ability to acquire, recall, and synthesize medical information in a way that is necessary for informed decision making.23–29 Studies have shown that stress and anxiety also interfere with risk perception, namely the ability to interpret risk information and formulate an accurate perception of risk.23,30 Additionally, patients' intention to undergo genetic testing has been shown to be more strongly related to perceived risk than actual risk.31–33 For instance, data demonstrate that an abnormal screening result generates anxiety.34,35 Such stressors, in turn, impact perceptions of risk and alter decision-making processes, often in favor of undergoing further diagnostic testing.24,32 Equally important in the setting of prenatal genetic screening, evidence indicates that shifting notions of risk perception are closely tied to values, beliefs, and preferences about the disease in question.34–38 As a result, concern and anxiety in the testing context have been shown to increase an individual's subjective beliefs about their personal degree of risk while increasing a sense of aversion to that specific risk.29,39

Health care providers must be prepared for these hurdles to informed consent for first trimester aneuploidy screening. However, there is a growing awareness of the challenges clinicians face to incorporate advances in genetic technology into patient care.40–44 A recent study on Down syndrome screening practices reported that less than half of sampled obstetricians considered themselves to be well qualified to counsel patients about Down syndrome risk and screening in general, 41% to counsel patients at elevated risk of Down syndrome, and 36% to counsel patients who screened positive for Down syndrome.40 At the same time, data gaps exist about the kind of informational resources patients need to make an informed decision or how to facilitate informed consent for these tests. A body of research is emerging about the development of decision aides to help patients navigate their prenatal genetic testing options.45,46 These instruments will play an important role in educating pregnant patients about genetic testing. However, much remains unknown about the decisional factors that influence how patients choose to proceed with prenatal genetic testing and the specific information patients need to make informed decisions about the first trimester aneuploidy screen. For instance, the notion of an educational mismatch is finding from our work. Our study shows that patients may prioritize a different set of decision-making factors than what clinicians customarily emphasize in the informed consent discussion. The standard rubric of informed consent includes indications, risks, benefits, and alternatives of aneuploidy screening. However, our data point to the fact that patients may rely on an extended set of decision-making factors, specifically the risk of anxiety associated with testing, options after the diagnosis of fetal Down syndrome, and preemptively exploring acceptable avenues if fetal aneuploidy is confirmed. These data will be vital to developing educational interventions that address the informed decision-making needs of pregnant women.

More broadly, our findings speak to larger issues regarding prenatal genetic testing. Our data show that pregnant women seem to be conflicted about aneuploidy screening in general and the choice to access this kind of fetal genetic information at any stage of the pregnancy. Our findings support similar observations noted by scholars in this field over the past 15 years that additional mechanisms should be in place to help patients through these complex decisions.47–50 Even before the advent of first trimester aneuploidy screening, debate abounded about the adequacy of resources in place to help pregnant women make informed, value consistent decisions about the use of prenatal genetic screening. What is additionally troubling is that the recent changes in prenatal genetic screening have unfolded without the resolution of such existing issues or the concurrent development of evidence-based mechanisms to mitigate them. The similarities that we have found in our data with earlier studies point to the fact that this must be a priority area of research.

Our study has brought to light several important considerations regarding the clinical use of first trimester aneuploidy screening. However, there are some limitations to this study that must be recognized. These qualitative data represent the opinions and experiences of one community of women. Thus, the study's findings may be limited in terms of its generalizability. In addition, we chose to use a brief educational video during the focus groups to bring all participants to a common level of knowledge about the aneuploidy screen in question. As first trimester aneuploidy screening is a relatively new procedure, we recognized the need to provide this information to achieve a level of dialog to explore the issues in question. Of note, there was a range of reproductive histories and ethnicities within the participant group, which serves as a strength despite the small sample size. A quantitative survey constructed with the key findings from the focus group is currently being conducted to assess the slope of these findings.

The availability of first trimester screening provides women the opportunity to make important personal choices early in the pregnancy. However, shifting the time frame of aneuploidy screening introduces a host of first trimester-specific factors that can negatively affect decision-making. At the same time, there are limited resources in place to help patients make informed decisions about these prenatal testing options. Evidence-based mechanisms are needed to facilitate informed consent for first trimester aneuploidy screening. Additionally, efforts to counter outdated and lingering assumptions about the risk of fetal aneuploidy and indications for screening, specifically those linking risk solely with advanced maternal age. Finally, timing and access to prenatal care is an issue that must also be addressed, so that patients may elect or defer first trimester aneuploidy screening in an informed manner. Without such resources in place, pregnant patients are at risk for engaging in prenatal aneuploidy screening without meaningful consent or, in other cases, declining testing without sufficient information. Given the importance of informed consent for prenatal genetic testing, it is critical that these barriers be prioritized in clinical research and health policy.

REFERENCES

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins ACOG Practice Bulletin 77: screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109: 217–227.

Saller DN, Canick JA . Current methods of prenatal screening for Down syndrome and other fetal abnormalities. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008; 51: 24–36.

Kazerouni NN, Currier B, Malm L, et al. Triple-marker prenatal screening program for chromosomal defects. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114: 50–58.

Driscoll DA, Gross S . Prenatal screening for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2556–2562.

Grossman D, Blanchard K, Blumenthal P . Complications after second trimester surgical and medical abortion. Reprod Health Matters 2008; 16: suppl 31 173–182.

Spencer K . Aneuploidy screening in the first trimester. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2007; 145C: 18–32.

Reddy UM, Wapner RJ . Comparison of first and second trimester aneuploidy risk assessment. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 50: 442–453.

Driscoll DA, Gross SJ . First trimester diagnosis and screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genet Med 2008; 10: 73–75.

Suther S, Goodson P . Barriers to the provision of genetic services by primary care physicians: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med 2003; 5: 70–76.

Marteau TM, Dormandy E . Facilitating informed choice in prenatal testing: how well are we doing?. Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 185–190.

van den Berg M, Timmermans DR, Ten Kate LP, van Vugt JM, van der Wal G . Are pregnant women making informed choices about prenatal screening?. Genet Med 2005; 7: 332–338.

Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM . Informed choice: understanding knowledge in the context of screening uptake. Patient Educ Couns 2003; 50: 247–253.

van den Berg M, Timmermans DR, ten Kate LP, van Vugt JM, van der Wal G . Informed decision making in the context of prenatal screening. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 63: 110–117.

Mulvey S, Wallace EM . Levels of knowledge of Down syndrome and Down syndrome testing in Australian women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 41: 167–169.

Jaques AM, Halliday JL, Bell RJ . Do women know that prenatal testing detects fetuses with Down syndrome?. J Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 24: 647–651.

Malone F, Canick J, Ball R, et al. First trimester or second trimester screening, or both, for Down syndrome. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2001–2010.

Reedy U, Mennuti M . Incorporating first trimester Down syndrome studies into prenatal screening. Obs Gyn 2006; 107: 167–173.

Strauss A, Corbin J . Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications 1998;

Gabbe S, Niebyl J, Simpson L . Obstetrics: normal and problem pregnancies, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier Science 2007;

Ohman SG, Grunewald C, Waldenstrom U . Women's worries during pregnancy: testing the Cambridge worry scale on 200 Swedish women. Scand J Caring Sci 2003; 17: 148–152.

Muller MA, Bleker OP, Bonsel GJ, Bilardo CM . Nuchal translucency screening and anxiety levels in pregnancy and puerperium. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 27: 357–361.

Finer LB, Henshaw SK . Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2006; 38: 90–96.

Frost CJ, Venne V, Cunningham D, Gerritsen-McKane R . Decision making with uncertain information: learning from women in a high risk breast cancer clinic. J Genet Couns 2004; 13: 221–236.

Hurley KE, Miller SM, Costalas JW, Gillespie D, Daly MB . Anxiety/uncertainty reduction as a motivation for interest in prophylactic oophorectomy in women with a family history of ovarian cancer. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001; 10: 189–199.

McNally RJ . Cognitive bias in the anxiety disorders. Nebr Symp Motiv 1996; 43: 211–250.

Persson I, Thurfjell E, Bergstrom R, Holmberg L . Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Nested case-control study in a cohort of Swedish women attending mammography screening. Int J Cancer 1997; 72: 758–761.

Leung W, Goldberg F, Zee B, Sterns E . Mammographic density in women on postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. Surgery 1997; 122: 669–673.

Coles ME, Heimberg RG . Memory biases in the anxiety disorders: current status. Clin Psychol Rev 2002; 22: 587–627.

Chapman G, Elstein A, Cognitive processes and biases in medical decision making. Chapman G, Sonnenberg F editors Decision making in health care: theory, psychology, and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2000; 183–210.

Watson M, Duvivier V, Wade Walsh M, et al. Family history of breast cancer: what do women understand and recall about their genetic risk?. J Med Genet 1998; 35: 731–738.

Bossuyt PM, Raaymakers TW, Bonsel GJ, Rinkel GJ . Screening families for intracranial aneurysms: anxiety, perceived risk, and informed choice. Prev Med 2005; 41: 795–799.

Marteau TM, Kidd J, Cook R, et al. Perceived risk not actual risk predicts uptake of amniocentesis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98: 282–286.

Shiloh S, Saxe L . Perception of risk in genetic counseling. Psychol Health 1989; 3: 45–61.

Abuelo DN, Hopmann MR, Barsel-Bowers G, Goldstein A . Anxiety in women with low maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein screening results. Prenat Diagn 1991; 11: 381–385.

Marteau TM, Cook R, Kidd J, et al. The psychological effects of false-positive results in prenatal screening for fetal abnormality: a prospective study. Prenat Diagn 1992; 12: 205–214.

Statham H, Green J . Serum screening for Down's syndrome: some women's experiences. BMJ 1993; 307: 174–176.

Khoshnood B, De Vigan C, Blondel B, et al. Women's interpretation of an abnormal result on measurement of fetal nuchal translucency and maternal serum screening for prenatal testing of Down syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 28: 242–248.

Georgsson Ohman S, Grunewald C, Waldenstrom U . Perception of risk in relation to ultrasound screening for Down syndrome during pregnancy. Midwifery 2009; 25: 264–276.

Lerner JS, Keltner D . Fear, anger, and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol 2001; 81: 146–159.

Driscoll DA, Morgan MA, Schulkin J . Screening for Down syndrome: changing practice of obstetricians. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 200: 459.e1–459.e9.

Rostant K, Steed L, O'Leary P . Prenatal screening and diagnosis: a survey of health care providers' knowledge and attitudes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 43: 307–311.

Tyzack K, Wallace EM . Down syndrome screening: what do health professionals know?. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 43: 217–221.

Yankowitz J, Howser D, Ely J . Differences in practice patterns between obstetricians and family physicians: use of serum screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 1361–1365.

Cleary-Goldman J, Morgan MA, Malone FD, Robinson JN, D'Alton ME, Schulkin J . Screening for Down syndrome: practice patterns and knowledge of obstetricians and gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107: 11–17.

Kuppermann M, Norton ME, Gates E, et al. Computerized prenatal genetic testing decision-assisting tool: randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 53–63.

Nagle C, Gunn J, Bell R, et al. Use of a decision aid for prenatal testing of fetal abnormalities to improve women's informed decision making: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BJOG 2008; 115: 339–347.

Rapp R . Testing women, testing the fetus. London: Routledge 1999;

Charo RA, Rothenberg KH, “The good mother”: the limits of reproductive accountability and genetic choice. Apple RD, Golden J, Rothenberg K, Thomson EJ editors Women and prenatal testing: facing the challenges of genetic technology. Columbus: Ohio State University Press 1994; 105–130.

Rothman BK, The tentative pregnancy: then and now. Apple RD, Golden J, Rothenberg KH, Thomson EJ editors Women and prenatal testing: facing the challenges. Columbus, Ohio State University Press 1994; 260–294.

Press N, Browner CH . Risk, autonomy, and responsibility: informed consent for prenatal testing. Hastings Cent Rep 1995; 25: suppl 3 S9–S12.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the KL2 award from the Cleveland Clinic/Case Western Reserve University CTSA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farrell, R., Dolgin, N., Flocke, S. et al. Risk and uncertainty: Shifting decision making for aneuploidy screening to the first trimester of pregnancy. Genet Med 13, 429–436 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182076633

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182076633

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Measuring informed choice in population-based reproductive genetic screening: a systematic review

European Journal of Human Genetics (2015)