Abstract

Purpose

This study examined challenges faced by families and health providers related to genetic testing for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Methods

This qualitative study of 14 parents and 15 health providers identified an unstandardized three-step process for families who pursue ASD genetic testing.

Results

Step 1 is the clinical diagnosis of ASD, confirmed by providers practicing alone or in a team. Step 2 is the offer of genetic testing to find an etiology. For those offered testing, step 3 involves the parents’ decision whether to pursue testing. Despite professional guidelines and recommendations, interviews describe considerable variability in approaches to genetic testing for ASD, a lack of consensus among providers, and questions about clinical utility. Many families in our study were unaware of the option for genetic testing; testing decisions by parents appear to be influenced by both provider recommendations and insurance coverage.

Conclusion

Consideration of genetic testing for ASD should take into account different views about the clinical utility of testing and variability in insurance coverage. Ideally, policy makers from the range of clinical specialties involved in ASD care should revisit policies to clarify the purpose of genetic testing for ASD and promote consensus about its appropriate use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous group of conditions characterized by persistent difficulties in verbal and nonverbal communication that impair social functioning.1 Ideally, a clinical diagnosis of autism is obtained through a multidisciplinary team evaluation that includes assessments of developmental history; speech, language, and intellectual abilities; and educational or vocational attainment.2 However, these “gold-standard diagnostic tools” have not been widely adopted in community-based practice because they are laborious, expensive, and resource-intensive.2

According to Devlin and Scherer3 “About 5–15% of individuals with ASD have an identifiable genetic etiology corresponding to known chromosomal rearrangements or single gene disorders; in addition, rare de novo or inherited copy number variations (CNVs) are observed in 5–10% of idiopathic ASD cases.” Five specialty organizations have promulgated recommendations related to genetic testing for ASD (Table 1), falling into three categories: (i) karyotype and fragile X testing only (American Academy of Neurology4 and American Academy of Pediatrics,5 (ii) chromosomal microarray (CMA) as a first-tier test (International Standard Cytogenomic Array Consortium6 and American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)7), and (iii) clinician discretion to determine which of the above three tests to order (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry8). Genetic testing for ASD is further complicated by variability in available test options, insurance coverage, and parental motivations for testing. In a 2012 qualitative study, most parents had never heard about genetic testing for ASD despite the availability of clinical testing for more than a decade.9 In another study 60% of parents of children with ASD reported that genetic testing was not recommended.10 These findings suggest that many providers are not adhering to professional recommendations and do not discuss genetic testing with their patients. When they do, there is inconsistency about what tests are offered.

Few studies have explored parental experiences and interest in genetic testing for individuals with ASD, or the views of different clinical specialists who care for patients with ASD. This paper reports on an empirical study that examined parental experiences with the multiple pathways to ASD genetic testing and the challenges that families face in the process. We also examine providers’ views on professional recommendations and their decisions about whether to pursue genetic testing for their patients with ASD.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment

Parents with at least one child diagnosed with ASD were eligible to participate in an interview to elicit their experiences with genetic testing of ASD. Parents were recruited in two ways. First, invitation letters were mailed to parents in advance of their child’s scheduled appointment at the University of Washington Center on Human Development and Disability (UW-CHDD) Autism Genetics Clinic in Seattle. These families were then approached at their initial genetics clinic visit and given additional information about the study. Second, parents were recruited through two listservs that function as discussion forums for families living with autism: the Families for Effective Autism Treatment of Washington, a nonprofit organization founded by families for families who have children with autism, and the Autism Information Exchange for parents employed by a large company. A listserv member or manager posted information about the study and parents who were interested in participating were invited to contact the study team directly. A total of 14 families were enrolled. Six families (families 1–6 in Table 3) were recruited through the UW-CHDD autism genetics clinic. The lead author (K.S.B.) observed a genetics clinic visit and, with permission, took notes during the appointments for each of these six families and invited the family members to participate in a follow-up interview. Three accepted (families 2, 3, and 5). An additional eight parents (families 7–14) were recruited through the listservs.

Health-care providers were invited to participate if they were involved in the diagnosis and care of children with autism including geneticists, neurologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, generalist and developmental pediatricians, and genetic counselors. We conducted a Google search using the terms autism, Washington State, and diagnosis to identify providers in the Puget Sound region with expertise in conducting diagnostic tests for autism in children. Most providers were identified from the Autism Speaks family resource website.11Table 2 lists the 14 diagnostic centers in the Puget Sound region that offer the majority of diagnostic services for autism in Washington State. After the first round of provider interviews, a snowball sampling technique was utilized to identify and recruit additional providers until a diverse group of perspectives and disciplines was achieved. A total of 23 providers were invited to participate, of whom 15 agreed. All of the interviewed providers are involved with autism diagnosis and/or genetic testing.

Interview guide

Parents were asked about their experiences with genetic testing of ASD, including the process, motivations for seeking testing, decision making, and overall thoughts and feelings. Providers were asked about the genetic testing process at their facility, personal views and practices regarding genetic testing, the potential effects of genetic testing, communicating with families, and returning results. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and de-identified. Audio recordings were destroyed after the accuracy of the transcripts had been verified. This study was approved by University of Washington Institutional Review Board, and all participants signed written consent forms.

Data collection

Interviews were completed with 11 families and 15 providers. Data reported for three families who did not participate in interviews were abstracted from the genetics clinic observation notes. Interviews were conducted from December 2012 through February 2014 by the lead author in person (n = 11) or by phone (n = 15) and ranged from 5 to 45 minutes (parents) or from 16 to 75 minutes (providers). Variability in interview length was directly related to whether or not families were offered testing; most questions focused on the testing experience, so interviews ended early if testing was not pursued. Providers’ interview length varied because of different levels of experience with genetic testing.

Data analysis

We employed content and thematic network analysis to address the research questions.12,13 Two authors (K.S.B., M.L.) independently coded three provider and four family interviews and reviewed the transcripts to reach agreement when divergent codes emerged to develop a codebook. All transcripts were then coded by the lead author (K.S.B.) using Dedoose software.14 Through an iterative process, coded data were analyzed to identify the main themes and how they relate to each other;13 these were then discussed with the research team to further refine and synthesize the concepts into organizing themes.

Results

Participants

The patients in this study ranged in age from 2 to 35 years, were living in Washington State, had a clinical diagnosis of ASD, and were offered different tests (Table 3). There were 10 male patients (71%) and 4 female patients (29%). The 11 parents interviewed were predominantly white (n = 10, or 91%), and 10/11 interviews (91%) were with the mother. Of the 15 providers (7 = female, 8 = male) interviewed, 4 were psychologists/psychiatrists, 4 pediatricians, 3 geneticists, 2 neurologists, and 2 genetic counselors.

Thematic analysis: pathways to genetic testing

Families and providers described a wide range of experience with genetic testing for ASD, which we summarize here as a three-step process. Step 1 is the clinical diagnosis of ASD, which can be done by one or more providers, practicing alone or as members of a team. Step 2 is the potential offer of genetic testing. For those offered testing, step 3 involves the parents’ decision whether to proceed with testing. While the process may seem straightforward, parents and providers describe barriers and complications that result in multiple paths to testing.

Step 1: initial diagnosis of ASD: who makes the diagnosis and recommendations?

ASD is diagnosed by a range of providers and in a variety of settings, most commonly in large tertiary centers (Table 2). One provider noted, “Most pediatricians aren’t going to make a diagnosis of autism. Most pediatricians, the vast majority, refer out to a tertiary center” (provider 3). Providers may work independently or as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Families who receive an autism diagnosis are typically offered a range of recommendations, which may include medical (including genetic testing), educational, behavioral therapy, and/or community resources, from their providers. One provider explained, “In autism we can look for diagnostic evaluation … and what you end up with is a list of 15 things. ‘You could try this, you could do this, try this, try this, here you go’” (provider 3).

In our study, three families (10, 11, and 13) were not offered genetic testing. A fourth family (8) asked their developmental pediatrician for genetic testing when it was not offered initially. Some families described choices about different therapies, referrals to specialists, or tests to pursue, but these did not include genetic testing. Other parents described genetic testing as one of many options, with little direction about the next steps to take after a diagnosis of autism was made. One parent said they were “just given that big three-ring binder and some book recommendations and told to find an ABA [applied behavior analysis] provider, pretty much” (parent 10).

Step 2: offering genetic testing

The second step in the pathway is offering genetic testing to families. Families may be offered genetic testing at different or multiple times (Table 3). Four patients (2, 3, 5, and 6) received genetic testing on two separate occasions. Additional testing may be offered because of evolving technology, introduction of a new provider, or the patient’s development of additional problems. For example, family 2 visited the UW-CHDD autism clinic when their now-adult child developed serious behavioral issues, many years after the diagnosis. Other families (1, 4, and 12) were not offered genetic testing at diagnosis but were offered testing later.

Who offers genetic testing?

Some families were offered genetic testing by the provider who diagnosed their child whereas others were referred to specialists for consideration of genetic testing. As shown in Table 3, many types of providers order genetic testing for ASD. Providers who believed that testing would be beneficial but who could not order genetic tests themselves (e.g., psychologists) referred the patient to an appropriate provider.

Families recruited through the UW-CHDD clinic (1–6) were referred to the medical genetics clinic to discuss ordering genetic tests. Other providers felt comfortable ordering the testing themselves. A developmental pediatrician stated, “A geneticist doesn’t need to see the ones that are negative … I’m doing the system a service by knowing enough about the recommendations, ordering the test, and if it’s negative it’s done” (provider 12).

However, developmental pediatricians do not always offer genetic testing; this specialty was involved in the care of five of the families we interviewed, but only three had discussions about genetic testing. Family 8 discussed genetic testing (and ultimately completed the testing) with a developmental pediatrician, but only after the parent asked about testing and expressed concern about recurrence risk. Family 5 discussed genetic testing with a developmental pediatrician and had chromosomal testing done years after their initial diagnosis. Family 14 discussed genetic testing with a developmental pediatrician when their child was first diagnosed and decided against testing because of difficulties obtaining a blood sample. Years later, they discussed it again with a neurologist because their child was going to be sedated for other tests, allowing genetic tests to be obtained as well.

Criteria for testing of ASD patients

Some providers in our study routinely referred ASD patients to a genetics clinic, others only in certain circumstances. The factors weighed included the provider’s comfort with ordering and interpreting the tests, accessibility of genetics clinics for the family, and the wait time to see a genetics provider. Many providers indicated that they refer ASD patients for genetic testing on a case-by-case basis, based on the presence or absence of clinical features such as dysmorphic characteristics, seizure disorder, multiple affected systems, severe developmental delay, or multiple family members with autism. One developmental pediatrician explained:

There’s a couple of different strategies—I can’t say that we have a consistent methodology. If I see a child with a number of risk factors, dysmorphic features, unusual head size, unusual family history, my preference would be to send that child to a geneticist to determine the most cost-efficient way to do the genetic evaluation. (Provider 4)

Overall, 12 of 15 providers mentioned using independent risk factors as their primary way to screen patients for genetic testing. One developmental pediatrician stated, “We were always taught that the more severe developmental delay that a child has, the more likely you are to find the genetic etiology and I still believe that’s true” (provider 12).

Lack of consensus about what tests to offer and when

Providers also noted that because of the diversity of disciplines involved in diagnosing ASD, there is no single guideline that all providers follow. Table 1 summarizes the different recommendations of guidelines referenced by providers. In reference to the ACMG recommendation to offer CMA testing to all patients diagnosed with ASD, one geneticist noted, “So I like to give them a choice and I’m willing to be criticized that I’m not delivering the standard of care if the family believes this is not in their best interest or they can’t tolerate the information that may come from there” (provider 13).

We found little provider consensus across medical specialties on what constitutes the standard of care. Although 12 providers reported feeling obliged to comply with the ACMG guidelines, one geneticist stated:

I feel a little manipulated by the national standards that this is the standard of care because I’m not sure if it really influences the management. I’m not sure I agree with that statement and I’m not sure where I stand on those—and my personal point of view is it’s good to know as much as you can about something and if this requires information that you can’t currently interpret, I’m okay with it but I recognize that the patients and their families are not always of the same mind. (Provider 13)

A developmental pediatrician stated, “I think so many things subconsciously go into our minds about how strongly or how ambivalently we make a recommendation” (provider 12). One psychologist simply stated, “I think that the background rate of adherence to guidelines is low” (provider 6).

Among providers at a given center, there may be disagreement regarding which guidelines to follow or how to best translate the recommendations into institutional protocols. Many questioned the utility of different genetic tests used in the context of ASD (including CMA) and said they are waiting for better testing before they commit families to the genetic evaluation process. A genetic counselor explained:

I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to go and meet with the neurodevelopment/autism clinic providers as part of their conversations related to autism, genetic testing, and a paper that was put out in the last year about the recommendations for what genetic testing should look like in this cohort of patients. It was really intriguing to hear those providers talk about their approach to testing because many of them really question the value of testing in this population … meaning that $2,000 for this chromosomal microarray test which may or may not give you an answer. (Provider 11)

One psychologist seemed frustrated that “we’re going to move it forward into clinical deployment before it’s ready for prime time” (provider 6). A geneticist was aware of the way this testing was being perceived by psychologists, stating, “I think basically [the psychologists] are uncomfortable with genetic testing and I think that they also—a lot of them still think of it as being purely in the research realm” (provider 7).

Providers recognized that while there may be a societal value to testing, it may not have value for individual families. As one psychologist put it, “It’s better for moving the science forward as opposed to actually being most helpful for families. So there’s some clinical utility but that’s limited for a small portion of kids with autism” (provider 3).

Step 3: Getting the test

Parental awareness

The final step in the pathway is completing the genetic test. Six families did not complete testing (families 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, and 13); of these, three were never offered testing (families 10, 11, and 13). Eight families (1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 14) had testing done, but of those, two families (1 and 6) declined to participate in a follow-up interview, one (7) never received their results, and one (8) received a positive result. The child with a positive result was found to have a duplication of chromosome 15q11.2-13.1. For that family, knowing the genetic basis for their child’s autism was helpful. They joined a support group of parents of children with the same genetic condition and are now aware of certain medical conditions associated with this syndrome, medications to avoid, and clinicians who specialize in providing for these children.

Insurance

Three families (3, 4, and 12) chose not to pursue testing after the diagnosis, primarily because their insurance would not cover the costs. One family (7) discussed genetic testing with their nurse practitioner and were referred to medical genetics, but insurance denied coverage, so they pursued genetic testing through a research study. However, the research protocol did not include returning results to participants.

Providers also noted difficulties with insurance companies. Provider 4 said, “It seems that most of the insurance plans are increasingly rejecting requests to pay for microarrays. Our lab here has implemented a policy in which unless there is preauthorization, they are not going to proceed with the test.” Provider 7 noted, “some insurers still specifically consider it investigational and won’t pay for it.” Provider 4 commented that the lack of insurance support conveyed a message to providers about the purpose or value of testing: “[the] funding for those tests, that’s tightened up quite a bit recently and it’s forced me to rethink the value of it.”

Discussion

While the ACMG guidelines7 state that everyone who is diagnosed with ASD should be offered a genetic evaluation, other guidelines4,5,6,8 offer different recommendations (Table 1). It is not surprising, therefore, that our provider and parent interviews describe considerable variability in the approaches to genetic testing, including whether or not testing is offered or discussed. No two families will necessarily have the same experience, as each patient’s journey depends on who makes the initial diagnosis, where they are seen, what is offered, what type of insurance they have, the questions they ask, and the nature of their symptoms.

Lack of consensus among providers on when and what tests to offer may be due to differences in professional guidelines coupled with the range of opinions about the relative weight of benefits compared to the burden of time, expense, and energy for families. For four of five families in our study who pursued genetic testing, the results had no impact on their child’s circumstances. One family received a positive result that provided clinical guidance. Although the number is small, our data are roughly consistent with the 6–15% rate for identifying a specific etiology in individuals with ASD reported by Schaefer and Mendelsohn.7

Even in the rare cases where genetic testing points to an etiology for a child’s autism, questions about the clinical utility of genetic testing for ASD remain, due to lack of definitive treatment or impact of most genetic test results. Our provider interviews suggest that the issue of clinical utility remains, in keeping with the lack of consensus on what genetic tests to offer and what guidelines to follow.

Our interviews indicate that many providers choose not to offer testing to families and many families are unaware of the option for genetic testing. Of the parents in our study, six did not obtain genetic testing and three had never been offered or discussed genetic testing with their providers. Our findings align with previous studies indicating that most parents of a child with ASD are unaware of genetic testing options.9,10 The resulting inconsistent practices have generated concerns among some providers. For example, Cuccarro et al.15 state, “the need to understand and improve on referral to genetic services for individuals with ASD is becoming more pressing.”

Our data suggest that testing decisions are influenced primarily by providers and secondarily by insurance carriers. The latter observation is consistent with documentation of poor coverage of ASD genetic testing.16 The interviews also demonstrate that lack of insurance coverage may discourage providers from ordering the test and raise questions about the clinical utility of such testing. Better insurance coverage might lead to more testing, even with existing questions of test utility, as is the case in other countries. For example, higher compliance with testing recommendations in France has been attributed to free access to care.10

Limitations to the generalizability of our study should be noted. Our study included a purposive sample of parents who were either seeking a genetics consultation or were active in online support groups, all in Washington State, where autism diagnostic services are primarily delivered in 14 diagnostic centers. The six families recruited from the UW autism genetics clinic tended to have older children and were referred to the study by a single medical geneticist, thus their experiences may have been particularly influenced by that provider’s perspective. To counter this, we expanded recruitment from listservs to get a more diverse group. Another limitation is that we did not seek information from families or providers about subdiagnoses (e.g., autism, Asperger, or pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified) or intellectual disability. As we did not differentiate the diagnoses, we are unable to assess whether this would have an impact on the pathway to testing. Our parent sample was mostly white and had resources to seek help, and is therefore not representative of parents with autism. Nevertheless, parents described a wide range of experiences that are probably applicable to many parents of children with autism. Our provider sample of 15 respondents represent the full range of specialties involved in the diagnosis of ASD, with a 65% response rate among eligible providers in the Puget Sound region, and thus is likely to represent the views of providers in this metropolitan region.

Our study is exploratory, involving a small number of parents and providers in the Puget Sound region. Further investigation of the experiences of a broader, more representative group of families and from providers in other regions of the country would be helpful. However, our data suggest that the pathway from a diagnosis of ASD to a genetic test is complicated and difficult for families to negotiate. Whether this process should include promotion of routine genetic testing for ASD, however, is not clear. Guidelines about genetic testing are inconsistent. Some of the inconsistency may reflect the rapidly changing technology, given that some guidelines were published more than 9 years ago. The varied experience reported by families and varied opinions reported by providers indicate there is also a lack of a clear standard of care.

Moving forward, providers should be aware of differing views about the clinical utility of testing and limitations in insurance coverage. Ideally, given the variation in practice noted in our study, policy makers should revisit policies to clarify the purpose of genetic testing, promote consensus about the appropriate uses of genetic testing in ASD, and develop information for parents that is balanced and comprehensive. Efforts to convene stakeholders—including provider specialties involved in the diagnosis and care of individuals with ASD, experts on test methodology, insurance providers, and parent/family representatives—to discuss the pros and cons of different approaches to testing would be helpful. Such an approach would not necessarily lead to uniform guidance about genetic testing for individuals with ASD, but could clarify the rationale and criteria for offering testing, including the delineation of areas of consensus and areas of persistent disagreement among different stakeholders. This is a process that will take time and energy and may be a moving target, as treatments, access, and insurance coverage are changing. However, currently the pathway from an ASD diagnosis to genetic testing is challenging, expensive, sometimes random and, as the interviews in this study suggest, often puzzling or dissatisfying to both patients and providers. Efforts to create a clearer and more transparent approach are needed so that all families with an autism diagnosis are given reliable information about genetic testing.

References

Jeste SS, Geschwind DH. Disentangling the heterogeneity of autism spectrum disorder through genetic findings. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:74–81.

Walsh P, Elsabbagh M, Bolton P, Singh I. In search of biomarkers for autism: scientific, social and ethical challenges. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011;12:603–612.

Devlin B, Scherer SW. Genetic architecture in autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2012;22:229–237.

Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Ashwal S et al. Practice parameter: screening and diagnosis of autism: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2000;55:468–79.

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With DisabilitiesJohnson CP, American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilitiesand the, American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2007;120:1183–1215.

Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 2010;86:749–764.

Professional Practice and Guidelines CommitteeSchaefer GB, Professional Practice and Guidelines CommitteeMendelsohn NJ, Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. Clinical genetics evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders: 2013 guideline revisions. Genet Med 2013;;15:399–407.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI)Volkmar F, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI)and the, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53:237–257.

Chen LS, Xu L, Huang TY, Dhar SU. Autism genetic testing: a qualitative study of awareness, attitudes, and experiences among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Genet Med 2013;15:274–281.

Amiet C, Couchon E, Carr K, Carayol J, Cohen D. Are there cultural differences in parental interest in early diagnosis and genetic risk assessment for autism spectrum disorder? Front Pediatr 2014;2:32.

Autism Speaks. Washington: Where to Get an Autism Diagnosis. 2015. https://www.autismspeaks.org/resource-guide/by-state/136/Where%20to%20get%20an%20Autism%20Diagnosis/wa; accessed on 7 April 2016.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288.

Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res 2001;1:385–405.

Dedoose version 7.0.23 SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC:: Los Angeles, CA, 2016. http://www.dedoose.com.

Cuccaro ML, Czape K, Alessandri M et al. Genetic testing and corresponding services among individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Am J Med Genet. A 2014;164A:2592–2600.

Henderson LB, Applegate CD, Wohler E, Sheridan MB, Hoover-Fong J, Batista DAS. The impact of chromosomal microarray on clinical management: a retrospective analysis. Genet Med 2014;16:657–664.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award P50 HG003374. N.A.G. was supported by K01 HG008818. We offer our thanks and our sincere appreciation to the families and providers who shared their experiences and perspectives with us. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barton, K., Tabor, H., Starks, H. et al. Pathways from autism spectrum disorder diagnosis to genetic testing. Genet Med 20, 737–744 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.166

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.166

This article is cited by

-

Detection of autism spectrum disorder-related pathogenic trio variants by a novel structure-based approach

Molecular Autism (2024)

-

Barriers to Genetic Testing Faced by Pediatric Subspecialists in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders (2023)

-

A Narrative Review of Genetic Testing for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the United States

Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2023)

-

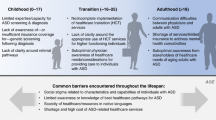

Tackling healthcare access barriers for individuals with autism from diagnosis to adulthood

Pediatric Research (2022)

-

Altered Metabolic Characteristics in Plasma of Young Boys with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2022)