Abstract

Purpose:

Population screening of three common BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jews (AJ) apparently fulfills screening criteria. We compared streamlined BRCA screening via self-referral with proactive recruitment in medical settings.

Methods:

Unaffected AJ, age ≥25 years without known familial mutations, were either self-referred or recruiter-enrolled. Before testing, participants received written information and self-reported family history (FH). After testing, both non-carriers with significant FH and carriers received in-person genetic counseling. Psychosocial questionnaires were self-administered 1 week and 6 months after enrollment.

Results:

Of 1,771 participants, 58% were recruiter-enrolled and 42% were self-referred. Screening uptake was 67%. Recruited enrollees were older (mean age 54 vs. 48, P < 0.001) and had less suggestive FH (23 vs. 33%, P < 0.001). Of 32 (1.8%) carriers identified, 40% had no significant FH. Post-test counseling compliance was 100% for carriers and 89% for non-carrier women with FH. All groups expressed high satisfaction (>90%). At 6 months, carriers had significantly increased distress and anxiety, greater knowledge, and similar satisfaction; 90% of participants would recommend general AJ BRCA screening.

Conclusion:

Streamlined BRCA screening results in high uptake, very high satisfaction, and no excess psychosocial harm. Proactive recruitment captured older women less selected for FH. Further research is necessary to target younger women and assess other populations.

Genet Med advance online publication 08 December 2016

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Identifying unaffected BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers offers prevention and early surveillance opportunities that reduce morbidity and mortality.1 Although direct-to-consumer testing exists,2 current medical referrals focus on persons who either are already affected or have significant family history.3,4 A major limitation of this approach is that approximately half of carriers lack suggestive family history,5,6 despite being at increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer.7

In Ashkenazi Jews (AJ), three common BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations have a combined carrier frequency of 2.5%.6,7 Our data7 suggest that testing for these mutations in AJ fulfills World Health Organization population screening criteria.8 A recent UK randomized control trial found that testing AJ regardless of family history identified significantly more carriers than family history–based testing without psychological sequelae.6 However, transitioning from testing limited numbers of high-risk individuals to population-wide screening may require new test delivery strategies. Pretest in-person genetic counseling of many individuals at low a prioi risk may not be feasible or warranted. Previous studies of population screening among AJ in Canada9 and in Poland10 used a streamlined approach. Before testing, participants received only written information. After testing, results were provided by telephone to carriers and to non-carriers with significant family history. Carriers were also offered in-person genetic counseling. Participants reported high satisfaction and, in the AJ study, no significant distress.9,10,11 However, these studies were performed with self-referred individuals who responded to newspaper notices. A formal screening program would proactively recruit participation among eligible individuals. The purpose of this study was to compare streamlined BRCA screening via proactive recruitment in medical settings with self-referral.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Chaim Sheba Medical Center and Clalit Health Services, and by the Israel National Ethics Committee.

Participants

Participants were AJ (self-defined as four grandparents of AJ origin), age ≥25 years, previously unaffected with cancer, and without a known familial BRCA mutation. Participants were not selected based on cancer family history.

Enrollment

Self-referral approximates self-initiated participation in an open-access screening program, whereas recruiter enrollment approximates proactive, medically initiated screening.

Recruiter enrollment

Recruiters offered participation in a mammography center, ambulatory clinics, and an executive screening clinic. Potential participants received written information. People meeting inclusion criteria who declined to participate (refusers) were asked to complete a short sociodemographic survey.

Self-referral

Information about the study was disseminated using posters and brochures provided in hospitals and clinics (including routine breast examination clinics). Interested persons could self-refer by contacting study personnel.

Pretest process

Participants provided written informed consent after receiving written information explaining the study, BRCA testing, and testing implications.

Enrollment questionnaire

All participants completed an enrollment questionnaire that requested (i) sociodemographic information, (ii) family history of cancer, and (iii) surveillance habits for breast and ovarian cancer.

Genetic testing

Testing for the AJ founder mutations BRCA1-185delAG (c.68_69delAG), BRCA1-5382insC (c.5266dupC), and BRCA2-6174delT (c.5946delT) was performed as previously published.7

Posttesting process

Participants were informed at enrollment that the post-test process would depend on their family history and test results, which were provided within 3 months.

A genetic counselor assessed family-history questionnaires before test results were available. Family history was classified as indicating no, low, moderate, or high likelihood for hereditary breast–ovarian cancer (HBOC) using previously published criteria7 (Supplementary Table S1 online). Non-carriers with family history indicating no or low likelihood for HBOC received a letter including test results and routine surveillance recommendations. Non-carriers with moderately or highly suggestive family history and all carriers (regardless of family history) received results by in-person genetic counseling, followed by a summary letter.

Psychosocial assessment

Self-administered questionnaires were sent 1 week after enrollment, before results were received (Q1), 6 months after enrollment, and after results were received (Q2). Questionnaires were e-mailed and Web-based when possible; if not, then they were mailed. They included six psychosocial measures:

-

1. General satisfaction with participation and testing (5-point scale score: 1–5; very dissatisfied to extremely satisfied).

-

2. Satisfaction with Health Decision scale (SWHD) (score range: 6–30; low to high satisfaction): SWHD measures satisfaction with health-care decisions,12 has good psychometric properties, and correlates with “decisional confidence.”13 It has been used to assess HBOC genetic counseling.14 Each of 6 items has a 5-point scale.

-

3. State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (score range: 6–24; low to high anxiety): The 6-item anxiety subscale of the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory15 is a validated, widely used measure of state anxiety. Respondents indicate how they feel “right now, at this moment” using a 4-point frequency scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “very much so” (4).

-

4. Impact of Events Scale (IES) (score range: 0–75; no to high distress): The IES is a 15-item self-report measure assessing current subjective distress in relation to a specific stressor,16 in this case BRCA testing. Frequency of intrusive and avoidant ideation and behaviors during the past 7 days is rated using a four-category frequency scale: “not at all” (0), “rarely” (1), “sometimes” (3), and “often” (5). A total score ≥30 indicates significant distress.16,17,18

-

5. Perceived Personal Control (PPC) (score range: 0–2): The PPC, a validated measure of genetic counseling outcomes, assesses counselees’ subjective perceptions of the degree of control they have over their genetic condition.19 It has high reliability19,20 and has been used in studies on HBOC predisposition testing.21,22,23 The score is the mean of 9 items, each scored 0–2.

-

6. Knowledge (score range: 0–10): Knowledge of breast cancer genetics and genetic testing was assessed using 10 true–false items (Supplementary Table S2 online) based on two published knowledge scales24,25 and modified to apply to individuals at low risk. Modifications were piloted in 20 patients and 10 breast cancer genetics professionals.

Statistical analysis

The mean value of continuous variables was compared using the t-test. Frequencies of categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Paired t-tests and McNemar test were used to compare paired continuous and categorical data, respectively. For multivariate analysis, linear regression and logistic regression were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. P values are two-tailed with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Study population

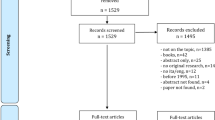

We enrolled 1,771 participants: 1,027 (58%) were recruiter-enrolled and 744 (42%) were self-referred. Sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Participant mean age was 52 years (SD = 13) and 79% (1,406/1,771) were female. Recruiter enrollees were older than self-referred participants (mean age 54 vs. 48 years, respectively; P < 0.001) and were therefore more likely to have ever been married ( Table 1 ). A family history consistent with a moderate to high likelihood of HBOC was more common in self-referred than in recruiter-enrolled participants (33 vs. 23%, respectively; P < 0.001).

Uptake of BRCA testing

Uptake could be evaluated among individuals offered enrollment by a recruiter. Of those, 1,027 (out of 1,530; 67%) consented to participate. Participants and refusers had similar age, gender, and child or daughter status (Supplementary Table S3 online). Recruitment location significantly affected participation rates, which were 55% in mammography centers, 73% in executive screening clinics, 81% in ambulatory clinics, and 92% when participation was offered by a gynecologist (P < 0.001). Recruitment location was the only significant predictor of uptake in multivariate analysis. Compared with ambulatory clinics, recruitment in a mammography center reduced participation by 2.5-fold (P < 0.001), whereas recruitment by a gynecologist increased participation by 3.3-fold (P = 0.005).

Genetic test results

Genetic testing was completed for all 1,771 participants. Thirty-two (1.8%) mutation carriers were identified: 16 (0.9%) BRCA1 carriers (185delAG—10 carriers and 5382insC—6 carriers), 15 (0.8%) BRCA2 6174delT carriers, and 1 BRCA1 and BRCA2 double carrier (185delAG and 6174delT). The carrier rate for females was 26/1,380 (1.8%), which was similar to that for males (6/365; 1.6%). The mean age of female carriers was 45.3 years (SD = 13.6), which was significantly younger than that of noncarriers, whose mean age was 51.4 years (SD = 12.8) (P = 0.02) ( Table 2 ). The mean age of male carriers was 48.0 years (SD = 16.7) compared with 52.2 (SD = 13.4) years for non-carriers (not significant NS). Carriers were more likely to have a suggestive family history (P < 0.001; Table 2 ). Nevertheless, 13/32 carriers (40%) had no or little likelihood of HBOC. The carrier rate was significantly higher in self-referred participants: 21/744 (2.8%) vs. 11/1,027 (1.1%) in recruiter enrollees (P = 0.006). However, family history was the only significant predictor of carrier status in multivariate analysis. Compared with participants with no family history, the odds ratios (ORs) for carrier status of participants classified as having low, moderate, or high likelihood for HBOC were 1.2, 3, and 4.5, respectively (P = 0.02).

Compliance with post-test genetic counseling for high-risk individuals

All 32 carriers received posttest counseling. Among non-carriers, 468/1,771 (26%) had suggestive family history. Compliance with posttest counseling in this group was 87% (413/468): 93% (245/264) among self-referred vs. 82% (168/204) among recruiter-enrolled participants (P = 0.002); compliance was 89% for women vs. 78% for men (P = 0.01). Enrollment type was the only significant predictor of counseling compliance in logistic regression, but its absolute effect was negligible (OR = 1.01 for self-referral versus recruiter enrollment; P = 0.01). Female gender had borderline significance as a predictor (P = 0.06) but had a greater effect (OR = 1.99). Age, education, having children, and family history were not significant predictors of post-test counseling compliance.

Psychosocial assessment

Response to questionnaires. The results described are for 1,255 participants because, due to technical difficulties, the first 516 participants did not receive questionnaires. The response rates were 67% (845/1,255) for Q1 (1 week after testing, before receiving genetic test results) and 50% (623/1,255) for Q2 (6 months after testing, after receiving results). Forty percent (497/1,255) of participants answered both Q1 and Q2, enabling paired analysis in this group.

In univariate analysis, participants who completed Q1 were younger than those who did not complete Q1 (mean age 50.8 vs. 52.0 years; P = 0.06). The Q1 response rate was higher for women than for men (51 vs. 36%; P < 0.001), among those with a moderate to highly suggestive family history (53 vs. 45% for participants with no to low likelihood of HBOC; P = 0.004), and among self-referred participants (56 vs. 43% for recruiter-enrolled participants; P < 0.001). In multivariate analysis, the following same factors significantly predicted greater Q1 response: female gender (P = 0.001), higher likelihood of HBOC (P = 0.03), and type of study enrollment (P < 0.001). However, the only substantial OR was for gender (OR = 1.66 for women vs. men). For family history and type of enrollment the OR was approximately 1 (1.055 and 0.999, respectively). Participants’ age and education levels did not affect the Q1 response rate. We also called a random sample of 50 nonresponders for Q1. Almost all indicated that they did not respond for technical reasons (e.g., time constraints or incorrect e-mail address).

Psychosocial outcomes. Questionnaire outcomes are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 . Comparisons of Q2 with Q1 ( Table 3 ) include only non-carriers because Q1 preceded knowledge of genetic status. Q2 outcomes for carriers are described separately ( Table 5 ).

Satisfaction with study participation:

In Q1, 91% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with study participation ( Table 3 ). Logistic regression indicated that greater perceived control (PPC score) predicted high satisfaction (OR = 7.6; P < 0.001), as did self-referral (OR = 2.5; P = 0.009). Among recruiter enrollees, in Q1 the recruitment site significantly affected satisfaction rates, which were 80% for gynecologist offices, 84% for executive screening clinics, 91% for mammography centers, and 93% for ambulatory clinics (P = 0.02, controlled for PPC). In the entire group, participant age, gender, having children, education level, family history, IES, and knowledge scores did not significantly predict satisfaction. In Q2, total satisfaction increased to 93% (satisfied/very satisfied) and remained higher among self-referred (96%) versus recruiter-enrolled participants (90%) (P = 0.02). Satisfaction increased over time. In Q2, more participants were very satisfied than at in Q1 (57 vs. 47%; P = 0.06 for paired analysis).

All other psychosocial outcomes were assessed using linear regression; each measure was a dependent variable and the independent variables were the sociodemographic characteristics and other measures ( Table 4 ). Satisfaction with participation had significant covariance with SWHD; therefore, only SWHD was included as a satisfaction measure in these analyses.

SWHD

Total mean SWHD score in Q1 was high (25.8/30; SD = 3.3) ( Table 3 ). Younger age, self-referral, higher PPC score, and lower IES and STAI-6 scores significantly predicted higher SWHD score, but these factors had only small absolute effects (e.g., self-referral increased SWHD score by 0.6 points; P = 0.003; Table 4 ). In Q2, SWHD score remained higher in the self-referred group (P = 0.012), but the difference decreased from 1.1 to 0.6 (of 30) points ( Table 3 ). In paired analysis, SWHD was higher in Q2 than Q1 (P = 0.004).

PPC (range 0–2)

In Q1, mean PPC score was 1.05 (SD = 0.5), which was 0.1 (out of 2) points higher in self-referred versus recruiter-enrolled participants (P < 0.001; Table 3 ). Higher SWHD scores, better knowledge, and lower anxiety (STAI-6) were significant but weak, predictors of the PPC score. For example, each 1-point increase in knowledge or SWHD scores increased PPC by only 0.03 points (P < 0.001) and 0.08 points (P < 0.001), respectively. Other variables did not affect PPC ( Table 4 ). Mean PPC score increased to 1.23 in Q2, and the 0.1-point difference between the two enrollment groups was conserved ( Table 3 ; P = 0.006). For participants who completed both questionnaires, PPC score was significantly higher in Q2 (P < 0.001), and the 0.2-point increase observed was within the range of observed effects of in-person genetic counseling (0.07–0.37).21,26

IES (0–75)

The mean IES score in Q1 was 5.8 (SD = 7.6), which was 0.8 (out of 75) points higher among self-referred participants (P = 0.02). IES of more than 30 (indicating high post-event distress) was reported by only 14 (1.7%) individuals: 11/398 (2.7%) self-enrolled and 3/417 (0.7%) recruiter-enrolled (P = 0.02; Table 3 ). In multivariate analysis, female gender, younger age, positive family history, lower SWHD scores, and higher STAI-6 scores were significant predictors of higher IES scores. IES score was 3.2 points higher for women versus men (P < 0.001). Other predictors were weaker; for example, IES score was higher by 0.07 points for participants with moderate to high HBOC likelihood versus those with no to low likelihood (P = 0.009; Table 4 ). In Q2, distress scores decreased slightly, nonsignificantly, to a mean of 5.2 (SD = 7.7) ( Table 3 ). Likewise, only 6/587 (1%) participants reported IES >30. No significant difference was found between enrollment groups. Paired analysis showed no significant change in IES scores over time.

STAI

Mean STAI-6 score in Q1 was 10/24 (SD = 3.5). Similar to the IES score, STAI-6 score was higher, although not significantly, among self-referred compared with recruiter-enrolled participants ( Table 3 ). Younger age, lower SWHD and PPC scores, and higher IES score were significantly associated with increased state anxiety but had weak absolute effects (e.g., a 0.1 point (of 24 points) increase in STAI-6 score was observed for every additional 1 point (of 75 points) in the IES; P < 0.001; Table 4 ). Paired analysis showed no significant change in anxiety over time.

Knowledge

Mean knowledge score in Q1 was 7.0/10 (SD = 2.5), which was higher for self-referred versus recruiter-enrolled participants (P < 0.001; Table 3 ). Female gender and university education increased knowledge scores very modestly (by 0.5 (P = 0.046) and 0.05 points (P = 0.01), respectively; Table 4 ).

In Q2, the mean knowledge score was slightly higher (7.1; SD = 2.4; NS versus Q1) and remained higher among self-referred versus recruiter-enrolled participants (7.5 (SD = 2.2) and 6.8 (SD = 2.5) respectively; P < 0.001). Paired analysis also showed no significant change in knowledge over time among non-carriers. For non-carriers with a suggestive family history who were invited for post-test genetic counseling, mean knowledge in Q2 was 7.6/10, which was significantly higher (P = 0.002) than for non-carriers without a family history.

Correlation between psychosocial measures

Distress scores (IES) were correlated with anxiety scores (STAI-6) (rp = 0.3; P < 0.001). PPC scores correlated with SWHD scores (rp = 0.56; P < 0.001) and with knowledge scores (rp = 0.25; P < 0.0001); they were inversely correlated with stress level (IES) (rp = −0.83, P = 0.02). Knowledge was also correlated with the SWHD score (rp = 0.2; P < 0.001).

Recommendation for BRCA screening

Participants were asked whether they would recommend BRCA population screening using the same process they experienced. In Q1, 677 (86%) indicated they would recommend screening, 7 (1%) were opposed, and 106 (13%) were unsure ( Table 3 ). Of those unsure, some mentioned, in an open remark, that they would support BRCA screening if they were assured that testing would be voluntary. The proportion of participants recommending screening was not affected by type of enrollment and increased with time, to 90% at in Q2.

Psychosocial outcomes in carriers versus non-carriers

Psychosocial outcomes in carriers were compared with those of non-carriers after participants received test results (Q2; Table 5 ). Satisfaction level, SWHD, PPC, and recommendation rate for population BRCA screening were similar. Significant differences were found for the distress and anxiety measures: mean IES score was 19.9 for carriers versus 4.9 for non-carriers (P < 0.001) and mean STAI-6 score was 12.6 for carriers versus 9.9 for non-carriers (P = 0.02). Knowledge scores were also significantly higher for carriers (8.7 vs. 7.1 for non-carriers; P < 0.001). Paired analysis in carriers showed increased knowledge over time (from 7.5 in Q1 to 8.8 in Q2; not significantly different in this small sample).

Discussion

This trial of population screening for common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unaffected AJ compares possible real-life strategies: recruitment by medical personnel (58%) or self-referral (42%). With a view toward large-scale screening,9,10 we used a streamlined process of pretest written information. After testing, in-person genetic counseling was provided for carriers and for non-carriers with a significant family history. Overall, more than 90% of participants reported high or very high satisfaction both 1 week and 6 months after testing, with significantly increased satisfaction over time. The majority would recommend population screening: 86% at 1 week and 90% at 6 months after testing. Only 1% were opposed and the remaining 10–13% were mainly concerned about screening remaining voluntary. Participation rate, measured among recruiter enrollees, was 67%, which was similar to the 71% rate in a recent UK study of AJ.6 Having children, specifically daughters, did not affect participation, suggesting personal risk assessment was the main motivation for testing. Compliance with post-test counseling was 100% for carriers and 89% for female non-carriers, showing that streamlining did not result in lack of follow-up, regardless of type of enrollment (OR = 1.01).

Compared with self-referral, recruiter enrollment in medical settings captured women less selected for family history. Among recruiter enrollees, 24% indicated a suggestive family history versus 35% of self-referred participants. However, both these rates are substantially higher than the ~10% background rate of breast/ovarian family history among AJ in Israel.7 Consistent with previous reports,7,9,10 40% of carriers identified in this study had no significant family history. Therefore, although family history is a significant motivator for screening, our results reiterate the importance of reaching women without such history. Proactive population-wide recruitment is a step in this direction, but it requires further refinement.

The mean ages of recruiter enrollees and self-referred participants were 54 and 48 years, respectively, which were similar to the mean ages of 54 and 49 years, respectively, observed in studies of AJ in the United Kingdom6 and Canada.9 In a self-referral study in Poland,10 the mean age of female carriers was 45.6 years, which is comparable to 45.3 years in this study. This is substantially older than optimal for cancer prevention in carriers because cancer risks increase sharply with age. Although risks are very low before age 30, by age 50, combined risks for breast cancer and ovarian cancer are 41 and 16% for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, respectively.7 In this and in previous studies of unaffected AJ,9 the carrier rate was lower than the expected 2.5%, probably because many carriers have already become affected by their late 40s and early 50s. To maximize cancer prevention through BRCA screening, it is imperative to develop and empirically validate strategies that engage younger women. This may require identifying concerns specific to this age group, as well as tailoring outreach approaches (e.g., utilizing social media). Empiric assessment is crucial. We originally expected higher uptake in women undergoing routine mammography, presuming this indicates an interest in preventive breast health. Although uptake at a mammography center was appreciable (55%), it was significantly lower than at other locales, perhaps because mammography-associated anxiety reduced receptiveness for additional testing.27 Conversely, recruitment in clinics and, particularly, recommendation by a physician significantly increased uptake (to >80%).

Recruitment site also affected satisfaction, ranging from 80% for gynecologist referral to 93% for ambulatory clinics. These results indicate the need to optimize recruitment schemes and sites to improve participation and satisfaction. Increasing access is clearly necessary. Despite a significant family history in 29% of participants, none were previously counseled or tested. This could be related to lack of awareness, limited familial communication, and bureaucratic (referral and payment) barriers that a screening program can overcome. Themes regarding access and familial communication, which emerged in extensive qualitative interviews, are reported elsewhere.28

Self-referred participants reported greater satisfaction with testing than recruiter enrollees, with higher SHWD scores and better sense of control (PPC), perhaps because their participation was self-initiated. However, their distress (IES) scores were also higher, consistent with the greater a priori risk of self-referred participants, who were younger and more likely to have a suggestive family history. At 6 months after testing, carriers and non-carriers showed similar satisfaction, SWHD, and PPC. Carriers had significantly increased distress and anxiety but also significantly greater knowledge. Compared with previous studies addressing psychosocial outcomes of HBOC genetic counseling and testing, we reported high SWHD scores (>25/30) for all groups (non-carriers, carriers; recruiter-enrolled, self-referred), similar to SWHD scores reported following traditional genetic counseling for BRCA testing.14 Distress (IES) was low (<6) at both time points for both self-referred and recruited non-carriers. In the Canadian AJ self-referral study, mean IES scores were 10.4 at baseline and 10.7 at 1 year. Studies of traditional BRCA counseling and testing in general reported higher distress levels,29,30 but most included women who were affected or at higher a priori risk, whereas in this study all participants were unaffected and 71% had no suggestive family history. Indeed, a suggestive family history, younger age, and lower satisfaction scores predicted higher distress, even though their effect size was small. Knowledge and education did not affect distress levels.

Although in non-carriers distress and anxiety were low and stable over time, among carriers, mean IES and STAI-6 scores at 6 months increased significantly to 19.9 (SD = 15.6) and 12.6 (SD = 4.2). Increased distress and anxiety have been consistently observed at 6 months to 1 year after disclosure of carrier status in studies of traditional, in-person genetic counseling.31,32,33 This distress declines over time34,35,36 and will be reassessed in future evaluations of study participants. Over time, carriers also undergo risk reduction surgeries that further reduce distress and anxiety.11,37 In the Canadian AJ study, mean IES score for carriers at 1 year was 23.8 (SD = 14.5) and decreased to 17.2 (SD = 14.5) at 2 years. Importantly, satisfaction with testing (SWHD) was as high in carriers as in non-carriers and, similar to all previous studies, distress and anxiety scores for carriers were generally below the threshold of clinically meaningful psychological dysfunction.38

The mean knowledge score 1 week after testing was 7.0/10 (SD = 2.5), similar to knowledge scores of ~70% in previous studies of education sessions or written information.39,40 Among women invited for posttest counseling, knowledge increased to 7.6/10 (P = 0.002); among carriers, knowledge at 6 months was increased substantially to 8.7/10. In qualitative interviews reported elsewhere,28 participants indicated that they regarded knowledge on a “need to know” basis, i.e., they sought knowledge only once they were found to be at risk. In this study, 69% of participants were at low a priori risk and remained so after testing. To summarize, psychosocial outcomes were generally favorable and similar to those observed both with traditional genetic counseling and in other non-family-history-based trials.

Study limitations

This study population is highly educated. Recruitment at mammography, executive screening, and breast surgeon clinics ascertained highly health-aware individuals. We did not aim to enroll a representative sample of the Israeli AJ population, but rather to explore alternative options of performing general BRCA1/BRCA2 screening. In this respect, the study population provides insight into the profile of potential participants in different versions of a screening program. The response rate to questionnaires was partial (67% for Q1 and 50% for Q2), but responders were representative of women study participants. The study was performed in one country. Sociocultural and health-system particulars may differ elsewhere.

Conclusion

Screening AJ for common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations using a streamlined process without in-person pretest counseling resulted in high (67%) uptake, very high (>90%) satisfaction, and very high post-test counseling compliance (89–100%). Most participants (71%) had no suggestive family history, and restricting in-person counseling to high-risk persons at the post-test stage resulted in no substantial psychosocial harm. Forty percent of carriers identified did not have a suggestive family history. Self-referral and medical-based recruitment captured different groups of women, suggesting that a multimethod approach will widen ascertainment. Current strategies target women who are around age 50, which is older than optimal for effective prevention. Further research is necessary to address screening implementation for younger women and for various societies and health systems.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High RisK Assessment: Breast and Ovarian (Version 2. 2016) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2016.

Francke U, Dijamco C, Kiefer AK, et al. Dealing with the unexpected: consumer responses to direct-access BRCA mutation testing. Peer J 2013;1:e8.

Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, Pearlman R, Wiesner GL ; Guideline Development Group, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee and National Society of Genetic Counselors Practice Guidelines Committee. A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genet Med 2015;17:70–87.

Moyer VA ; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:271–281.

King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB ; New York Breast Cancer Study Group. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science 2003;302:643–646.

Manchanda R, Loggenberg K, Sanderson S, et al. Population testing for cancer predisposing BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in the Ashkenazi-Jewish community: a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:379.

Gabai-Kapara E, Lahad A, Kaufman B, et al. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:14205–14210.

Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med 2007;9:665–674.

Metcalfe KA, Poll A, Royer R, et al. Screening for founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in unselected Jewish women. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:387–391.

Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Byrski T, et al. Direct-to-patient BRCA1 testing: the Twoj Styl experience. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006;100:239–245.

Metcalfe KA, Mian N, Enmore M, et al. Long-term follow-up of Jewish women with a BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation who underwent population genetic screening. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;133:735–740.

Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, et al. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: the satisfaction with decision scale. Med Decis Making 1996;16:58–64.

Kasparian NA, Wakefield CE, Meiser B. Assessment of psychosocial outcomes in genetic counseling research: an overview of available measurement scales. J Genet Couns 2007;16:693–712.

Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, et al. Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:442–452.

Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31 (Pt 3):301–306.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979;41:209–218.

Cella DF, Mahon SM, Donovan MI. Cancer recurrence as a traumatic event. Behav Med 1990;16:15–22.

Zilberg NJ, Weiss DS, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: a cross-validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982;50:407–414.

Berkenstadt M, Shiloh S, Barkai G, Katznelson MB, Goldman B. Perceived personal control (PPC): a new concept in measuring outcome of genetic counseling. Am J Med Genet 1999;82:53–59.

Smets EM, Pieterse AH, Aalfs CM, Ausems MG, van Dulmen AM. The perceived personal control (PPC) questionnaire as an outcome of genetic counseling: reliability and validity of the instrument. Am J Med Genet A 2006;140:843–850.

Albada A, van Dulmen S, Spreeuwenberg P, Ausems MG. Follow-up effects of a tailored pre-counseling website with question prompt in breast cancer genetic counseling. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:69–76.

Rothwell E, Kohlmann W, Jasperson K, Gammon A, Wong B, Kinney A. Patient outcomes associated with group and individual genetic counseling formats. Fam Cancer 2012;11:97–106.

Zilliacus EM, Meiser B, Lobb EA, et al. Are videoconferenced consultations as effective as face-to-face consultations for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic counseling? Genet Med 2011;13:933–941.

Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, et al. BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. A prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. JAMA 1996;275:1885–1892.

Van Riel E, Wárlám-Rodenhuis CC, Verhoef S, Rutgers EJ, Ausems MG. BRCA testing of breast cancer patients: medical specialists’ referral patterns, knowledge and attitudes to genetic testing. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:369–376.

Pieterse AH, van Dulmen AM, Beemer FA, Bensing JM, Ausems MG. Cancer genetic counseling: communication and counselees’ post-visit satisfaction, cognitions, anxiety, and needs fulfillment. J Genet Couns 2007;16:85–96.

Consedine NS, Magai C, Krivoshekova YS, Ryzewicz L, Neugut AI. Fear, anxiety, worry, and breast cancer screening behavior: a critical review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:501–510.

Lieberman S, Lahad A, Tomer A, Cohen C, Levy-Lahad E, Raz A. Population screening for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations: lessons from qualitative analysis of the screening experience. Genet Med, in press. doi:10.1038/gim.2016.175.

Pieterse AH, Ausems MG, Spreeuwenberg P, van Dulmen S. Longer-term influence of breast cancer genetic counseling on cognitions and distress: smaller benefits for affected versus unaffected women. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:425–431.

Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Hughes C, Main D, Isaacs C, Lerman C. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing on psychologic distress in a clinic-based sample. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:514–520.

Meiser B, Butow P, Friedlander M, et al. Psychological impact of genetic testing in women from high-risk breast cancer families. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:2025–2031.

Watson M, Foster C, Eeles R, et al.; Psychosocial Study Collaborators. Psychosocial impact of breast/ovarian (BRCA1/2) cancer-predictive genetic testing in a UK multi-centre clinical cohort. Br J Cancer 2004;91:1787–1794.

Nelson HD, Fu R, Goddard K, et al. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer: Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, 2013.

Arver B, Haegermark A, Platten U, Lindblom A, Brandberg Y. Evaluation of psychosocial effects of pre-symptomatic testing for breast/ovarian and colon cancer pre-disposing genes: a 12-month follow-up. Fam Cancer 2004;3:109–116.

Calzone KA, Prindiville SA, Jourkiv O, et al. Randomized comparison of group versus individual genetic education and counseling for familial breast and/or ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3455–3464.

Beran TM, Stanton AL, Kwan L, et al. The trajectory of psychological impact in BRCA1/2 genetic testing: does time heal? Ann Behav Med 2008;36:107–116.

van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Lodder LN, et al. Long-term psychological impact of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation and prophylactic surgery: a 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3867–3874.

Graves KD, Vegella P, Poggi EA, et al. Long-term psychosocial outcomes of BRCA1/BRCA2 testing: differences across affected status and risk-reducing surgery choice. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:445–455.

Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, et al. Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:148–157.

Skinner CS, Schildkraut JM, Berry D, et al. Pre-counseling education materials for BRCA testing: does tailoring make a difference? Genet Test 2002;6:93–105.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (NY) (to E.L.L.). For assistance in patient recruitment, we thank Judy Kop (Hala Breast Clinic, Jerusalem), Sharona Hujja (Women’s Health Center, Clalit Health Services, Jerusalem), Dorina Katzenellenbogen and Michal Chemi (Institute of Medical Screening, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer), and Haviv Gabai (Terem Clinic, Modi’in). For administrative assistance, we thank Carmit Cohen, Halel Dolinsky, Vered Colthof, and Yael Keren.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

(DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lieberman, S., Tomer, A., Ben-Chetrit, A. et al. Population screening for BRCA1/BRCA2 founder mutations in Ashkenazi Jews: proactive recruitment compared with self-referral. Genet Med 19, 754–762 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.182

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.182

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Diagnostic yield of genetic screening in a diverse, community-ascertained cohort

Genome Medicine (2023)

-

Residential Locale Is Associated with Disparities in Genetic Testing-Related Outcomes Among BRCA1/2-Positive Women

Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023)

-

Attitudes and interest in incorporating BRCA1/2 cancer susceptibility testing into reproductive carrier screening for Ashkenazi Jewish men and women

Journal of Community Genetics (2022)

-

Primary care physician referral practices regarding BRCA1/2 genetic counseling in a major health system

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2022)

-

Rate of breast biopsy referrals in female BRCA mutation carriers aged 50 years or more: a retrospective comparative study and matched analysis

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2022)