Abstract

Purpose:

The potential of interactive multimedia to improve biobank informed consent has yet to be investigated. The aim of this study was to test the separate effectiveness of interactivity and multimedia at improving participant understanding and confidence in understanding of informed consent compared with a standard, face-to-face (F2F) biobank consent process.

Methods:

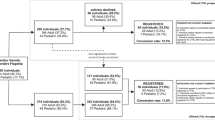

A 2 (face-to-face versus multimedia) × 2 (standard versus enhanced interactivity) experimental design was used with 200 patients randomly assigned to receive informed consent. All patients received the same information provided in the biobank’s nine-page consent document.

Results:

Interactivity (F(1,196) = 7.56, P = 0.007, partial η2 = 0.037) and media (F(1,196) = 4.27, P = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.021) independently improved participants’ understanding of the biobank consent. Interactivity (F(1,196) = 6.793, P = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.033), but not media (F(1,196) = 0.455, not significant), resulted in increased participant confidence in their understanding of the biobank’s consent materials. Patients took more time to complete the multimedia condition (mean = 18.2 min) than the face-to-face condition (mean = 12.6 min).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated that interactivity and multimedia each can be effective at promoting an individual’s understanding and confidence in their understanding of a biobank consent, albeit with additional time investment. Researchers should not assume that multimedia is inherently interactive, but rather should separate the two constructs when studying electronic consent.

Genet Med 18 1, 57–64.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biobanks collecting genetic material for research report considerable interest in using online portals and technologies such as computerized kiosks and tablet computers (tablets) to obtain informed consent.1,2 Informed consent promotes deliberate, voluntary participation in research and is important in biobanking given the potency of genomic information, the open-ended nature of biobank-supported research, and constraints on privacy and confidentiality.3 However, traditional face-to-face (F2F) consent processes pose challenges for biobanks.

Of the many types of biobanks, one subset is designed to support human health research using human biological samples and associated data.4 Obtaining informed consent for many of these biobanks is resource intensive and costly, requiring trained consenters to staff multiple recruitment points in clinical and/or community settings.5 Information in biobank consent materials also presents unique challenges. Individuals are typically asked to consent to future research studies that can be described only in the most general terms. Many are faced with information that requires a challenging level of genetic and genomic literacy.6 Studies have found that individuals misunderstand issues such as the risks of biobanking to privacy and confidentiality, ownership of samples, and the disclosure of individual results from genomic research.7 Thus both the efficiency and effectiveness of informed consent in promoting an adequate understanding of biobank participation are in need of improvement.

Electronic delivery of informed consent

A potential alternative to more traditional methods of obtaining consent is to automate the process and deliver information via a website or stand-alone computer program. Improvements in electronic delivery have made possible a shift in the consent format from text to multimedia (MM), including the addition of graphics, audio narration, and video. Electronic technologies can shift F2F delivery of consent information to methods that provide to patients more control over the pace of delivery and more engagement with research concepts through interactivity and other proactive instructional strategies.

Electronic delivery of study information also offers the potential to reach more participants using less staff time. Tablets, for example, can become a portable, paperless means of presenting consent information and documenting consent. Online availability provides broader access and allows participants to review consent information at their own pace, possibly even in their homes. Touchscreen technology can be used to capture participant signatures. Electronic tools can also support digital document storage and efficient retrieval, as well as ongoing education about a biobank’s activities, the (non)disclosure of research results, and recontact with participants.8

Multimedia

Research has yet to demonstrate that electronic consent (e-consent) processes communicate study information more effectively than traditional F2F methods. Efforts to improve participants’ understanding of information presented in the consent process for research through electronic media, primarily MM, have proved challenging.9 Some interventions have been successful at improving research participants’ understanding,10,11 whereas others have not.8 Most studies have compared MM methods to F2F methods without considering the theoretical underpinnings of the delivery strategies or carefully controlling variables across conditions. Mahnke et al.12 posited that the inconsistency in MM study results may be the result of a lack of rigorous development of MM and alternative materials.

This study applied theories of human perception and cognition to MM instruction13 in designing a MM informed consent presentation. According to dual coding theory,14 people process information through two simultaneous pathways: verbal (words and symbols) and spatial (pictures and movement). Well-designed instruction capitalizes on MM and the ability to combine visual and auditory information13,15 and strategically presents information through both modalities to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of instruction.13,16,17,18

In addition, cognitive load theory suggests that MM can be designed to enhance learning by maintaining an optimal level of cognitive load, the amount of information in use by working memory.19,20,21 By selecting content and designing the presentation of instruction to optimize load, learning engages but does not overwhelm the learner.20,22,23 To optimize cognitive load, designers focus on both the content and the delivery (e.g., how much information is presented and how it is organized) to improve participant learning.

Interactivity

Whereas studies of MM informed consent for research have had inconsistent results,9 use of interactive (e.g., test–feedback) strategies to engage participants in the consent process have generally shown improved understanding of informed consent information.24,25 Because definitions of interactivity differ across domains (computer science, communication studies, psychology), an empirically verifiable definition of “interactivity” is difficult to identify and even harder to apply to informed consent.26,27,28,29,30 Defined in the most general terms common among theorists, similar to Yacci’s31 “loop,” interactivity consists of three parts: (i) a prompt, (ii) a response from the participant, and (iii) feedback to the response.

In a standard consent session, F2F discussions between participants and researchers can be highly interactive in the broadest sense of the term. On hearing information they do not understand, participants may ask questions and receive feedback about those questions from the researcher. Although this is interactivity, it is unstructured and inconsistent, and the standard consent process does not ensure that a patient-driven dialogue occurs. However, interactivity can be structured and made consistent through strategically placed multiple-choice questions (i.e., prompts), which ask for a response from the participant and feedback to correct misconceptions or reinforce correct responses. Questions can be specifically targeted to improve understanding of difficult concepts. We label this type of interactivity “enhanced interactivity.” For this study, we included this structured interactivity, which could be controlled and thus potentially improve our understanding of the effect of interactivity on the consent process.

The interactive, MM presentation reported here is based on these distinct but interconnected concepts of MM and interactivity. Other ways of designing electronic and interactive MM consent are possible.9 Because producing interactive, MM materials can be time consuming and expensive, researchers need good theory and evidence-based principles to maximize their investment. This study was designed to test the hypothesis that MM and interactivity each would improve understanding and confidence in the understanding of a biobank’s informed consent.

Materials and Methods

Overview

A prospective, randomized study was integrated into the ongoing recruitment process for a comprehensive biobank at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City, Iowa. The University of Iowa Biobank collects saliva samples (with the option to collect blood and tissue) directly from patients for storage and future research. Informed consent is obtained using a nine-page consent document containing segments on the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, and informational elements required by the federal code of regulations on informed consent.32 The consent document addresses all 15 topics that experts suggest need to be addressed in biobank consent documents.3 The document is presented to eligible individuals as part of an opt-in, broad consent process developed with the institution’s institutional review board from data showing a statewide preference for an opt-in, active consent model.33

The Biobank and institutional review board permitted the researchers to enroll patients in the Biobank after randomization into one of four consenting conditions. Because the study involved experimental procedures for the consent process, participants’ comprehension of the information was assessed, and participants were automatically provided additional instruction for any missed assessment questions before enrollment in the Biobank. To avoid confusing individuals with two consent processes, potentially contaminating data, a waiver of consent/authorization of consent was obtained for this minimal-risk study.

Any patient approached by the Biobank in 2013 was considered eligible for the study. This included patients in dermatology, rheumatology/immunology, pulmonology, and family medicine clinics and those recruited by the Biobank through posters, fliers, ResearchMatch.org, and announcements distributed on the medical campus and in universitywide e-mail blasts and newsletters. To maintain consistency with Biobank procedures, research associates (RAs) were trained by the Biobank supervisor to conduct F2F consent and collect specimens. Training included specific points to emphasize during the consent process. In addition, researchers for this study trained the RAs on the study’s protocol and how to use the interactive and MM components. Mock consent sessions were practiced until RAs reported a moderate level of comfort with the study protocol.

Study conditions

This study tested the effectiveness of adding MM and enhancing interactivity on participants’ understanding of and confidence in their understanding of biobank consent information using a 2 (F2F versus MM) × 2 (standard versus enhanced interactivity) experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to receive informed consent using one of four processes:

-

F2F standard interactivity—paper consent document with standard researcher–participant discussion (control)

-

F2F enhanced interactivity—paper consent document, researcher–participant discussion, and 13 targeted, interactive questions

-

MM standard interactivity—paper consent document converted to an electronic slideshow with text, graphics, and verbatim narration of the text

-

MM enhanced interactivity—MM consent procedure as above and 13 targeted, interactive questions

All four conditions received the same information in the Biobank’s nine-page paper consent document.

Face-to-face conditions. The F2F standard interactivity condition was the standard informed consent process used by the Biobank. RAs reviewed the informed consent document with participants and answered any participant questions. In the F2F enhanced interactivity condition, the informed consent document was reviewed as in the F2F standard interactivity condition. However, 13 stoppage points were added, where the RAs asked participants scripted multiple-choice questions about critical elements of the consent, such as the purpose of the Biobank, sample types, and the risks and benefits of participation. After each question, RAs provided scripted feedback based on the participants’ response, reinforcing correct answers and clarifying misconceptions. RAs were trained for consistency in their communication style and feedback for both F2F conditions.

MM conditions. For the MM conditions, a PowerPoint-type slide show was developed. Cognitive load theory principles for effective MM learning were used to guide the chunking of text and selection of supporting graphics. The words from the paper consent document were divided (“chunked”) across slides, with graphics added to some slides to reinforce specific concepts, yielding a 93-slide presentation. All text was narrated verbatim. Hyperlinks were not used, and participants were not allowed to skip pages.

Tablets were used to present the Flash-based MM module. Participants could adjust the volume or mute the audio and could move forward or backward in the slideshow. The slideshow was incorporated into a delivery system developed by a commercial company (Patient Education Institute, Coralville, IA) with experience in patient education software using Flash-based Web technologies.

In the MM standard interactivity condition, participants were presented the slideshow, including the exact text from the consent document, graphics, and narration of the text. The MM enhanced interactivity condition included all slides from the MM standard interactivity condition, with the addition of the 13 interactive questions also asked in the F2F enhanced interactivity condition. Upon answering the interactive questions, participants received automated feedback based on their responses, reinforcing correct answers and clarifying misconceptions.

Participants were provided a paper copy of the consent document to look at during the consent process. In keeping with the Biobank’s consent practices, participants were encouraged to ask questions of RAs at any time during the consent process. RAs were not blinded to the conditions, nor could they be blinded to the interactive questions. However, the assessment questions (i.e., knowledge, satisfaction, demographics) for all conditions were provided on tablets. Thus RAs were not privy to the assessment questions or participants’ performance on those questions (outcome measures).

Formative evaluation. Various stakeholders participated in a formative evaluation of the MM slide show (evaluating chunking and graphics) and the interactive components (questions and feedback) for the enhanced interactivity conditions. Ethics consultants with expertise in biobanking, two Biobank directors, and an institutional review board chair participated in a first-round evaluation by completing a heuristic evaluation form.34 Next, five community members participated in two iterative rounds of evaluation, completing the MM enhanced interactivity module using think-aloud protocols35 and a debriefing with study investigators. The research team used stakeholder feedback, whenever feasible and appropriate, to improve the presentation. One notable change as a result of stakeholder feedback was the addition of a preliminary statement that participants would be asked questions and that the questions were for their benefit in the enhanced interactive conditions. Some graphics were modified or replaced and interactive questions were refined based on stakeholder feedback.

Outcome measures. To assess understanding of the information presented in the informed consent, a two-part assessment was developed modeled on the design for cancer clinical trials by Joffe et al.36 and the adaptation for biobanking consent by Ormond et al.7 Participants in all conditions completed the same assessment on a tablet using an online survey format. RAs were present during the assessment to answer participant questions or address technical problems.

The understanding of consent portion of the assessment contained 27 true/false statements covering the eight essential components of informed consent as specified in the federal regulations32 ( Table 1 ). For each item, participants could agree, disagree, or declare they were unsure about the statement. Following Ormond et al.7 and Joffe et al.,36 participants received 100 points for each correct response, 50 points for unsure responses, and 0 points for incorrect responses. Total points were averaged to yield an understanding consent score between 0 and 100 for each participant.

The confidence in understanding portion of the assessment consisted of 23 questions in which participants rated their confidence from 1 (“I didn’t understand this at all”) to 5 (“I understood this very well”). The confidence in understanding items were summed, averaged, and normalized in accordance with the equation provided by Joffe et al.36 ((Average confidence – 1) × 25) to create a confidence score.

In addition, participant consent time was calculated as the time elapsed (in seconds) from the beginning of the consent to the end of the consent, before participants began the assessment instruments. For all conditions, this included time during which RAs answered any of the participant’s questions.

Data management and analysis. To test the hypothesis that MM and enhanced interactivity would improve participant understanding and confidence, the outcome measures (understanding of consent, confidence in understanding, and consent time) were analyzed using 2 × 2 factorial multivariate analysis of variances, with media (F2F versus MM) and interactivity (standard versus enhanced) as independent variables, in SPSS version 21 (IBM, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY. see http://www-01.ibm.com/support/docview.wss?uid=swg21476197). Responses to open-ended, qualitative questions probing participants’ likes, dislikes, and suggestions were reviewed and coded by two independent coders. Coders developed a code book and met several times with a study principal investigator to refine the code book and coding categories.

Results

Sample

Two hundred individuals (50 per condition) participated in the study. Participants had a mean age of 47 years (range 18–86 years), were more likely to be women (76%), and were predominantly Caucasian (96%). Participants were well educated: 79% reported at least a college degree or higher. Almost one of every four (24%) reported a total household income of $100,000 or more.

Understanding of the biobank consent

Testing the hypothesis that MM and enhanced interactivity would improve participant understanding (media × interactivity multivariate analysis of variance on understanding consent scores), main effects for both interactivity (F(1,196) = 7.56, P = 0.007, partial η2 = 0.037) and media (F(1,196) = 4.27, P = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.021) were statistically significant, although the interaction between interactivity and media was not (F(1,196) = 0.004, not significant). Based on main effects, individuals in the enhanced interactivity conditions (collapsed across type of media) demonstrated better understanding (mean = 94.7) than those in the standard conditions (mean = 92.3). Similarly, individuals in both standard and enhanced MM conditions (collapsed across level of interactivity) demonstrated better understanding (mean = 94.4) than those in the F2F conditions (mean = 92.6) ( Figure 1 ). For the total sample (N = 200), the average understanding of consent score was 93.5.

Although average understanding was high, differences between groups on certain critical items were of note ( Table 2 ). For example, fewer than half of the participants in the F2F standard interactivity (48%) and just over half of those in the F2F enhanced interactivity (58%) conditions, compared with most of the MM participants (standard interactivity 82%, enhanced interactivity 86%), correctly understood that the Biobank allowed access to samples and health information by outside researchers (not affiliated with the University of Iowa). Almost half of the F2F standard interactivity participants (42%) misunderstood that the Biobank could not guarantee that their privacy and confidentiality would never be violated, compared with 18% of the participants in the MM standard interactivity, 20% in the MM enhanced interactivity, and 24% in the F2F enhanced interactivity groups.

Participant confidence in understanding

Testing the hypothesis that MM and enhanced interactivity would improve participants’ confidence in their understanding of the Biobank consent (media × interactivity multivariate analysis of variance on confidence scores), the main effect for level of interactivity was statistically significant (F(1,196) = 6.793, P = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.033), although media (F(1,196) = 0.455, not significant) and the interaction between interactivity and media (F(1,196) = 0.502, not significant) were not. In other words, individuals who received enhanced interactivity (13 multiple-choice questions) reported higher confidence in their understanding of the Biobank consent (mean = 97.9) compared with individuals in the standard interactivity conditions (mean = 96.3) ( Figure 2 ). For the total sample (N = 200), the average confidence score was 97.1.

Participant consent time

The multivariate analysis of variance (media × interactivity) on consent time revealed that both main effects for media (F(1,195) = 42.15, P < 0.001) and interactivity (F(1,195) = 29.94, P = 0.001) were statistically significant, although the interaction of interactivity and media was not (F(1,196) < 0.001, not significant). Collapsing across interactivity, participants in the MM conditions took more time to complete the consent (mean = 18.2 min) than those in the F2F conditions (mean = 12.6 min). Collapsing across media, participants receiving enhanced interactivity took more time to complete the consent (mean = 17.8 min) compared with those in the standard conditions (mean = 13.1 min). Participants in the MM enhanced interactivity condition took twice the time (mean = 20.6 min) to complete the consent compared with those in the F2F standard interactivity condition (mean = 10.3 min) ( Figure 3 ). The average elapsed time for the total sample (N = 196) was 15.4 min. Times for four participants were excluded because of missing data.

Attitudinal data

Using three open-ended questions, all study participants were asked what about the Biobank’s informed consent process they liked, disliked, and suggested for improvement. A total of 93 participants (46.5%) responded to at least one of these questions. Participants liked elements of all four study conditions. Likable elements of the MM conditions included the tablet and the interactive interface, the touchscreen and the “simple and direct” interface, the recorded verbal narration of the consent text, and the graphics. Likable elements of the F2F conditions included being “well explained,” “quick,” and “easy”; its interactivity by virtue of the presence of a consenter; and the perceived professionalism, “humor,” and “friendliness” of the consenter.

The duration of the consent process, as well as the perceived “redundancy” of some of the content in the consent document, was disliked by some participants in all four conditions. Duration of consent was a more prominent theme among participants in the MM conditions compared with the F2F conditions. Participants in the MM enhanced interactivity, however, which took the most time, did not criticize the duration of the consent process more than those in the MM standard interactivity group.

Suggestions for improving the biobank consent process included shortening the presentation, bulleting key information, and adding a short video to the MM presentation. Participants also suggested making the informed consent document available online and providing it before patients’ appointments.

Decision to enroll

Of the 200 participants, 4 (2%) chose not to enroll in the Biobank after completing the informed consent. Two were in the MM enhanced interactivity condition, one was in the MM standard interactivity condition, and one was in the F2F standard interactivity condition.

Discussion

Results from this study suggest that interactivity and multimedia are at least as good as, and perhaps better than, the Biobank’s standard F2F consent process at promoting understanding of the information presented in its informed consent document. Thus, incorporating interactivity and/or multimedia into a biobank’s consent process is one option for improving the process. Converting a biobank’s informed consent document to multimedia delivery by chunking text into slides, adding relevant graphics, and narrating the text benefited consent participants. Enhancing interactivity by adding multiple-choice questions with feedback improved the understanding of and confidence in the informed consent information for participants in both MM and F2F conditions. Comparing understanding of the F2F standard interactivity group with that of the MM enhanced interactivity group results in a large effect size (Cohen d = 0.67), suggesting that further study of this combination is warranted. Given the individual effects of multimedia and interactivity, however, researchers should not assume that multimedia is inherently interactive; rather, they should separate the two constructs when studying e-consent.

Results suggest that interactivity, which has not been treated as a separate construct in past multimedia research, deserves more attention. Adding multiple-choice questions with feedback offered a relatively easy and straightforward means of improving understanding, even in a F2F consent process. This means that enhanced interactivity can be incorporated into different delivery approaches, as this study illustrates. Other forms of interactivity, such as repetition and elaboration of information upon incorrect answers to questions37 or extended discussions with researchers based on question responses,38 should be studied as potential ways to improve interactivity in multimedia informed consent.

Biobanks will need to consider the tradeoff of improved participant understanding against increased participant time. Although participants in the MM conditions understood the material better, the gains were small and the MM conditions took more time for participants to complete than the F2F conditions. MM participants likely listened to all the slide narration, similar to reading the complete informed consent document, whereas RAs in the F2F conditions summarized the main points.

The qualitative feedback from study participants suggests that interactive multimedia is well tolerated but that the duration of a biobank consent process and redundancy may be problematic from a participant standpoint, regardless of how the information is presented. Participant feedback suggests that biobanks should consider providing staff-assisted consent options in addition to electronic processes for people who prefer a “human touch” and/or a paper document. Some individuals may prefer to listen to the audio narration in a multimedia slideshow, whereas others may prefer to read the text without narration. Preferences for interactivity may also vary. Research into the feasibility and benefits of providing the consent document online before any formal consent process in the clinic environment is also warranted. Multimedia consenting may be one of several options (i.e., in the form of a “menu-type” approach) offered to accommodate a diverse population with different levels of technology access, physical and perceptual ability, literacy, and other capabilities.

Biobanks should also consider that interactive multimedia consenting tools require a number of developmental steps. Formative evaluation and community consultation12 provide key insights into stakeholder needs and preferences with respect to the usability of e-consent. Evaluation processes used in this study resulted in improvements to the materials, which may have improved participant usage and satisfaction.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted at a single, Midwestern, nonurban institution with a primarily Caucasian and relatively well-educated sample. Because of the small group sizes, comparison of racial/ethnic differences or differences in recruitment settings was not possible. Further study of these findings with a more diverse population in different regions of the country and different recruitment settings is warranted. In addition, the lack of RA blinding to study conditions may have affected results. RA exposure to the interactive questions in the F2F enhanced interactivity condition may have influenced their handling of the standard F2F condition, accounting in part for the relatively high mean understanding score of participants in this condition. Researchers may want to consider using two sets of RAs in similar future research—one set devoted to multimedia and another to F2F conditions—to minimize possible contamination.

Finally, this study produced little data on whether e-consent might affect participation in biobanks. In addition, biobanks need to have more information about how e-consent processes affect staff time and patient relationships.

Conclusion

Biobanks are diverse entities that may benefit in multiple ways from electronic interfacing with research participants. Issues of time and costs for developing electronic materials, computer access, user preference, and integration with electronic patient records will need to be addressed in efforts to harness the benefits of electronic informed consent. From an ethical and legal standpoint, e-consent processes need to be at least as good as standard F2F consent processes at promoting informed, deliberate choices about research participation. Results from this study, showing improvement in understanding and confidence in the understanding of a biobank informed consent document, indicate the potential for improving the biobank consent process using interactive multimedia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Simon CM, Klein DW, Schartz HA. Traditional and electronic informed consent for biobanking: a survey of U.S. biobanks. Biopreserv Biobank 2014;12:423–429.

Thiel DB, Platt J, Platt T, et al. Testing an online, dynamic consent portal for large population biobank research. Public Health Genomics 2015;18:26–39.

Beskow LM, Dombeck CB, Thompson CP, Watson-Ormond JK, Weinfurt KP. Informed consent for biobanking: consensus-based guidelines for adequate comprehension. Genet Med 2015;17:226–233.

Simeon-Dubach D, Watson P. Biobanking 3.0: evidence based and customer focused biobanking. Clin Biochem 2014;47:300–308.

Ahmed FE. Biobanking perspective on challenges in sample handling, collection, processing, storage, analysis and retrieval for genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics data. Anal Methods 2011;3:1029–1038.

Kaphingst KA, Facio FM, Cheng MR, et al. Effects of informed consent for individual genome sequencing on relevant knowledge. Clin Genet 2012;82:408–415.

Ormond KE, Cirino AL, Helenowski IB, Chisholm RL, Wolf WA. Assessing the understanding of biobank participants. Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A:188–198.

Chalil Madathil K, Koikkara R, Obeid J, et al. An investigation of the efficacy of electronic consenting interfaces of research permissions management system in a hospital setting. Int J Med Inform 2013;82:854–863.

Nishimura A, Carey J, Erwin PJ, Tilburt JC, Murad MH, McCormick JB. Improving understanding in the research informed consent process: a systematic review of 54 interventions tested in randomized control trials. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:28.

Karunaratne AS, Korenman SG, Thomas SL, Myles PS, Komesaroff PA. Improving communication when seeking informed consent: a randomised controlled study of a computer-based method for providing information to prospective clinical trial participants. Med J Aust 2010;192:388–392.

Rowbotham MC, Astin J, Greene K, Cummings SR. Interactive informed consent: randomized comparison with paper consents. PLoS One 2013;8:e58603.

Mahnke AN, Plasek JM, Hoffman DG, et al. A rural community’s involvement in the design and usability testing of a computer-based informed consent process for the Personalized Medicine Research Project. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:129–140.

Mayer RE. Multimedia Learning, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York, 2009.

Low R, Sweller J. The modality principle in multimedia learning. In: Mayer RE (ed). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press: New York, 2005:147–158.

Mayer R. Introduction to multimedia learning. In: Mayer RE (ed). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press: New York, 2005:1–16.

Mayer RE. Cognitive theory and the design of multimedia instruction: an example of the two-way street between cognition and instruction. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 2002;2002:55–71.

Mousavi SY, Low R, Sweller J. Reducing cognitive load by mixing auditory and visual presentation modes. J Educ Psychol 1995;87:319–334.

Sadoski M, Paivio A. Imagery and Text: A Dual Coding Theory of Reading and Writing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, 2001.

Schnotz W, Kürschner C. A reconsideration of cognitive load theory. Educ Psychol Rev 2007;19:469–508.

Sweller J, Van Merrienboer JJ, Paas FG. Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educ Psychol Rev 1998;10:251–296.

Van Merrienboer JJ, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory and complex learning: recent developments and future directions. Educ Psychol Rev 2005;17:147–177.

Chandler P, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cogn Instr 1991;8:293–332.

Mayer RE, Moreno R. Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educ Psychol 2003;38:43–52.

Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA 2004;292:1593–1601.

Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 2011;31:151–173.

Downes EJ, McMillan SJ. Defining interactivity: a qualitative identification of key dimensions. New Media and Society 2000;2:157–179.

Heeter C. Interactivity in the context of designed experiences. Journal of Interactive Advertising 2000;1:3–14.

Jensen JF. The concept of interactivity—revisited: four new typologies for a new media landscape. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Designing Interactive User Experiences for TV and Video. ACM: New York, NY, 2008.

Kiousis S. Interactivity: a concept explication. New Media and Society 2002;4:355–383.

Koolstra CM, Bos MJ. The development of an instrument to determine different levels of interactivity. International Communication Gazette 2009;71:373–391.

Yacci M. Interactivity demystified: a structural definition for distance education and intelligent CBT. Educational Technology 2000;40:5–16.

Office for Human Research Protections, US Department of Health and Human Services. General requirements for informed consent (45CFR46.116). 45 C.F.R. Sect. 46.116, 2009, http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html. Accessed 20 November 2014.

Simon CM, L’heureux J, Murray JC, et al. Active choice but not too active: public perspectives on biobank consent models. Genet Med 2011;13:821–831.

Alessi SM, Trollip SR. Multimedia for Learning: Methods and Development, 3rd edn. Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, 2001.

Krug S. Usability test script: Advanced Common Sense, 2012, http://sensible.com/downloads-dmmt.html. Accessed 18 July 2012.

Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:139–147.

Wirshing DA, Sergi MJ, Mintz J. A videotape intervention to enhance the informed consent process for medical and psychiatric treatment research. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:186–188.

Coletti AS, Heagerty P, Sheon AR, et al.; HIV Network for Prevention Trials Vaccine Preparedness Study. Randomized, controlled evaluation of a prototype informed consent process for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;32:161–169.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Human Genome Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R21HG006293).

The authors thank Joyce Craig, Abe Klein, Jamie L’Heureux, Jenni Rigdon, and Laura Shinkunas, as well as Jeff Murray, University of Iowa Biobank Director, for their assistance with and support of this study. In addition, the authors thank the following consultants for their excellent feedback: Wendy Foth, Wendy Wolf, and Jennifer McCormick. Excellent feedback from Andrew Bertolatus, Betsy Chrischilles, Lauris Kaldjian.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, C., Klein, D. & Schartz, H. Interactive multimedia consent for biobanking: a randomized trial. Genet Med 18, 57–64 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.33

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.33

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ten years of dynamic consent in the CHRIS study: informed consent as a dynamic process

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Assessing the stability of biobank donor preferences regarding sample use: evidence supporting the value of dynamic consent

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

A training and education program for genome medical research coordinators in the genome cohort study of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization

BMC Medical Education (2019)

-

Facilitating Informed Permission/Assent/Consent in Pediatric Clinical Trials

Pediatric Drugs (2019)

-

Optimising informed consent for participants in a randomised controlled trial in rural Uganda: a comparative prospective cohort mixed-methods study

Trials (2018)