Abstract

Purpose:

This study investigated how genome sequencing results affect health behaviors, affect, and communication.

Methods:

We report on 29 participants who received a sequence result in the ClinSeq study, a cohort of well-educated, postreproductive volunteers. A mixed-methods design was used to explore respondents’ use, communication, and perceived utility of results.

Results:

Most participants (72%) shared their result with at least one health-care provider, and 31% reported subsequent changes in the health care they received. Participants scored high on the Positive Experiences subscale and low on the Distress subscale of a modified version of the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment. The majority (93%) shared their result with at least one family member. Participants described deriving personal utility from their results.

Conclusion:

This article is the first to describe research participants’ reactions to actionable sequencing results. Our findings suggest clinical and personal benefit from receiving sequencing results, both of which may contribute to improved health for the recipients. Given the participants’ largely positive or neutral affective responses and disclosure of their results to physicians and relatives, health-care providers should redirect concern from the potential for distress and attend to motivating patients to follow their medical recommendations.

Genet Med 18 6, 577–583.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an increasing number of research participants undergo exome and genome sequencing, there is growing debate about the development of guidelines on whether and how to return results (result-return guidelines). This is often contextualized within a larger debate about how to return research results to participants more broadly. Some have argued that researchers should be prepared to share individual results out of respect for their participants or in situations when there is a possibility of benefit to the participant.1,2 However, others suggest that there may be some harm in disclosing results that have no clinical utility.3 Several publications1,2,4 have recommended including research participants’ perspectives in the development of result-return guidelines and emphasize the need for empirical research on the outcomes of receiving genetic testing results. Some important outcomes to consider include the impact of the results on health-care behaviors, the communication of results within families, and the effects of results on psychological well-being.5 To our knowledge, there have been no reports of the impact of genome sequencing results on any of these outcomes.

Studies have explored the responses of research participants and the general population to anticipated return of results from genome sequencing,6 direct-to-consumer genetic profiles,7 and gene panels.8 These studies found that most individuals are enthusiastic about their hypothetical results, experience little distress, and express intentions to use their results to improve their personal health. However, there are several characteristics of genome sequencing results, including their breadth and uncertainty, that differ in degree from single-gene testing results. Genome sequencing has the potential to generate multiple results with varying implications for personal health, which may or may not be related to the patient’s main motivation for testing or emanate from their personal or family history. Sequencing results are more likely to be unexpected, and participants who receive them are less likely to have experience with the condition they are at risk for than recipients of single-gene test results. These differences are likely to affect how participants respond to and act on results. In the future, sequencing is expected to increasingly take genetic testing results out of the context of family risk and rare disease and integrate them into mainstream medicine because of their ability to guide health management in a predictive, personalized way.9 This exploratory study aims to generate hypotheses about the ways that receipt of results may resemble those of single-gene testing. Specifically, we describe whether the receipt of results in the context of differing motivations and family experiences affects relevant outcomes, such as compliance with screening recommendations and communication of results within a family.

Another important factor to consider in developing result-return guidelines is personal utility,10 which refers to outcomes that make a result valuable for reasons beyond clinical health benefits. Personal utility may include making practical preparations for the future, experiencing greater awareness of personal health behaviors and choices, or even satisfying curiosity.11 Study participants and members of the general population alike have cited these factors as motivators for receiving results,12,13 but it is unknown whether or how participants will perceive personal utility when faced with actual results.

Kohane and Taylor14 suggest that without knowing more about how participants view their results, we are unable to adequately frame the harms and benefits of disclosure because “personal views and values shape the benefits of even painful knowledge for a participant.” Our study provides preliminary findings regarding the impact of receiving an individual genetic result on health behaviors, communication of results, affect, and perceptions of personal utility for a subset of participants in an exome sequencing study.

Materials and Methods

Participants were recruited from the ClinSeq study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00410241), which was designed to pilot the application of clinical exome and genome sequencing. Study participants were largely self-referred and consented to receive four general types of results: those that predispose to preventable or treatable conditions, those that predispose to conditions that are not preventable or treatable, those that establish carrier status, and those of uncertain clinical significance.15 At the time of enrollment in the study, participants provided data on their race and ethnicity from a list of options provided by the study, which is required for annual reporting metrics by the National Human Genome Research Institute’s institutional review board. As results became available, participants were contacted via phone and offered the opportunity to receive them. Results were considered urgent if significant health risk was involved and actions could be taken to mitigate that risk. It was recommended, rather than merely presented as an option, that participants choose to receive such results.

Returned results were validated in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA)-compliant process and disclosed during a counseling session with a geneticist and genetic counselor at the National Institutes of Health. The sessions typically occurred within 3 weeks of the telephone call offering the results and took about 1 hour. If a participant was unable to travel to the National Institutes of Health, their result was disclosed via telephone. The counseling sessions provided information on the condition(s) the participant was at risk for, basic genetics and inheritance of the result, recommendations for screening for and treating the condition, recommendations for testing relatives, and psychosocial counseling. Participants received a copy of the CLIA report at their counseling session (or in advance of their telephone counseling session) and were sent a letter summarizing their result and our recommendations within 4 weeks of the session. All participants who received a result pertaining to cardiomyopathy or arrhythmia were offered screening for the condition(s) at the National Institutes of Health.16

All participants who had received one sequencing result with personal health implications and were not involved in previous focus groups on return of results preferences6 were eligible to participate (n = 46). Each eligible participant was contacted up to three times via telephone, secure e-mail, and postal mail about the study.

A mixed-methods design was used to encourage participants to elaborate on their experience of receiving sequencing results while also gathering quantitative data. We developed a semistructured interview guide that explored the medical and affective impact of sequence results, personal utility of results, whether and how results were shared within families, and preferences for receiving future results. The guide began with open-ended questions to allow original ideas and perspectives to arise. This was followed by closed-ended questions to assess the disclosure of results to health-care providers, use of specific screening tests, and disclosure of results to family members. A modified version of the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) was administered orally. The MICRA is a 23-item scale designed to assess test-specific distress using three subscales: Distress (six items; a = 0.86), Uncertainty (nine items; a = 0.77), and Positive Experiences (four items; a = 0.75).17 Our version was modified to refer to test results, not specifically to cancer. Two coauthors (P.D.C. and M.F.W.), who were trained in interview techniques by a senior investigator (B.B.B.), conducted the interviews by telephone.

The interviews lasted 30 minutes, on average, and were audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded using NVivo 10 software (QSR International). An initial codebook was developed based on the interview guide, and then iteratively revised with input from both coders. Each interview transcript was independently coded by two coauthors who did not conduct the interview (P.D.C., T.C.H., or S.C.), and discrepant codes were reviewed and most were reconciled for 80% agreement. Upon completion of coding, the data were analyzed to identify common themes and patterns. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) was used to compute summed responses, averages, and SDs for responses to the quantitative scales.

The National Human Genome Research Institute’s institutional review board approved the study. All participants gave verbal consent to participate in the interview study at the time of their recruitment. Participants were not compensated for their participation in the ClinSeq study or the interview study.

Results

Participants

Thirty-one participants agreed to participate in the interviews, for a response rate of 67%. The majority of participants who did not participate did not respond to recruitment attempts and did not give a reason for their nonresponse. Two interviews were not recorded and thus not included in the analysis. Twenty-three of the participants received urgent results that pertained to risk for cancer, hyperlipidemia, cardiomyopathy, or arrhythmia, and it was recommended, rather than merely presented as an option, that they elect to receive their result. Seven participants received a result related to risk for cardiomyopathy or arrhythmia and were screened for the condition at the National Institutes of Health. Two participants received results via telephone. None of the participants were aware of the genetic variant we shared with them before participation in our study. The length of time between result disclosure and completion of the interview ranged from 3 months to 4 years. No differences were found between those who had recently received their results and those who received them years before the interview.

Most participants were white and had at least a college education. They ranged in age from 52 to 71 years, and 52% were men ( Table 1 ). These demographic characteristics are consistent with those of larger samples of the ClinSeq population.12,18 The majority of results pertained to conditions that can be screened for and/or treated and that are included on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics’s list of genes and variants recommended for return of incidental findings19 ( Table 2 ).

Impact on health care

Quantitative data. Most participants (72%) shared their result with at least one health-care provider; however, the majority of participants (69%) did not report any changes to their health care following the receipt of their result. Of those who did experience changes to health care, five reported that they underwent cancer screening based on their result, two had screening for heart disease, one had a skin exam, and one underwent an eye exam (Supplementary Table S1 online). No participants reported receiving screening that was inappropriate for their result.

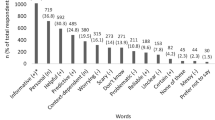

Qualitative data. Participants valued their results for disease prevention and early detection for themselves or their family members even though many did not report any changes to their health care. The participants who did not share their results with a health-care provider explained that they did not think it would affect their health care or that “it just didn’t seem to be relevant” (female, 60 years old, SGCE result). Most participants (n = 25) sought information about the variant and its associated health condition by searching online a few times soon after receiving their result.

Affective impact

MICRA data. Participants generally had high scores on the Positive Experiences subscale (mean = 15.2, SD = 5.6, range: 0–20) and low scores on the Distress (mean = 1.7, SD = 3.9, range = 0–30) and Uncertainty subscales (mean = 4.3, SD = 7.0, range: 0–45).

Qualitative data. Most participants (n = 25) reported that their result had either a positive or neutral impact on their affect. Positive outcomes included feeling relieved that the result was not about a more serious condition, reassured that they were already following the appropriate health-care recommendations, and pleased to be able to seek out surveillance. Most participants (n = 27) reported that their feelings about receiving their result became more positive over time as they had time to adapt.

Most participants (n = 17) mentioned that their family history influenced the emotional impact of their result. Both positive and negative family histories for the condition related to the result were mentioned as reassuring: participants with a known family history felt they already knew and were managing their risk, whereas those with a negative family history minimized the likelihood that they would be affected since none of their family members had been.

So I was doing everything appropriate. So there was no sense of, “Oh my God, I have to do something now that’s different. I have to now take some new action” or “Oh my God, I’m failing to do something that I should have been doing,” there is none of that. (Male, 71 years old, APOB result)

The other thing is that no one in my family, on either side of my family—and I have a big family—and they never had kidney cancer or collapsed lung. So, I do want my son to get screened…and I will get a kidney scan every couple of years, whatever the recommendation is but…I think if somebody told me I had some other thing I would be more upset. (Female, 67 years old, FLCN result)

Another factor that influenced the emotional impact of results was age. Most study participants were over age 60 and concluded that if they had not already developed symptoms of the condition, they were unlikely to do so in the future. Similarly, several participants said that their existing health problems were more concerning than their test result.

I was surprised, maybe a little bit concerned at first until I had an opportunity to digest all the information in the report, high risk factors for certain types of cancer are only minimally elevated. I have far more concerns about other aspects of my health than I do that. (Male, 66 years old, BRCA1 result)

Other participants noted that their positive emotional response to their result was not surprising because they would not have enrolled in the study if they did not feel they could cope with their personal results.

This is me. I can handle things better when I have a name to it. You know, whatever it is, don’t keep me guessing. Tell me what I have. Tell me what I need to do, what’s the plan? (Female, 69 years old, MYH7 result)

Less commonly, people had ambivalent feelings about their result. These participants generally had positive feelings about the potential personal health benefit and availability of screening, but felt worried or sad about learning their risk.

So that’s obviously a big benefit that may prevent me from getting colon cancer again. So that’s the positive. The negative side is that, you know, and I thought about this, is that I have to think about the fact that I’m a little bit a higher risk of getting colon cancer or other cancers, not just colon cancer. (Male, 69 years old, PMS2 result)

Negative affective responses to learning a result were far less common. In both of such cases, the participants described feeling surprised at the result they received. One participant said that she thought the result would pertain to heart disease and was unprepared to learn about risks for cancer. Another participant had strong preferences against receiving a result for hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome because he did not have any living female relatives.

Impact on communication

Objective data. The majority of participants (93%) disclosed their result to at least one family member. More participants shared their results with their daughters than with their sons. Even when hereditary breast ovarian cancer–related results, which have greater health implications for females than males, were removed from the analysis, more participants shared their result with their daughters (100%) than their sons (83%). Of the participants who had a living parent, 55% shared their result with at least one parent, and 70% of participants told at least one sibling.

Qualitative data. The majority of participants (n = 18) emphasized the importance of the information being easy to understand. Receiving results in simple terms helped them not only understand their result but also bolstered their confidence in being able to share the result with their family members.

And it was explained to me very, I mean obviously we are novice, we don’t know. We are not doctors and we don’t understand all the language and everything. And they did absolutely a great job of explaining in really simple terms, I mean. I explained it, you know, to my relatives, to my daughter, my sister in the same terms they gave it to me. So it was done very well. (Male, 69 years old, PMS2 result)

Participants were divided on whether they felt obligated to share their result with their family or considered it an individual choice. The participants who described disclosure as an obligation commonly reported sharing their result widely so that their family members would be aware of their risk.

And so what I basically did, I just went down the whole paternal lineage and I identified as many, just about everybody who is still alive and I put together a memo and an e-mail and sent it to everybody. (Male, 71 years old, APOB result)

On the other hand, participants who viewed disclosure as an individual choice were more likely to describe a process of selective disclosure. They cited a variety of factors in deciding whom to share with, including the age of their relatives, whether someone was likely to worry about the result, the closeness of their relationship with a relative, and the likelihood that the relative would be interested in the result.

Participants who had children sometimes mentioned that the decision to share their result with their children took additional factors into account. Those included feeling a responsibility to protect and make decisions on behalf of the family, a desire for openness within the family about health issues, and motivation to get results for the benefit of the entire family.

With my son, I did not ask whether he wanted to know because I felt that there was something that was my responsibility and it was his responsibility towards his children. So, you know, that is what I gave them. (Female, 68 years old, PROS1 result)

Personal utility

Participants in the study also described elements of personal utility in receiving their results. One of the most commonly reported experiences was increased self-awareness, particularly with regard to the impact of health choices.

Yeah, you don’t think about it, you really think you’re Superman. I mean that was the shock to realize I wasn’t a Superman and I wasn’t overcoming something that was deep in my being and I inherited from my father…and to realize that my father, who was a relatively sedentary machinist, tool and die maker, and he has been working in the shop…that notwithstanding all of my exercise, which was about 100 times more than he ever did, I was still in exactly the same trajectory. (Male, 71 years old, APOB result)

Another common theme for participants was increased vigilance. This referred not to increased screening or surveillance, but to being more self-aware, engaged with family members on health issues, and motivated to be healthy in general.

I think knowing that I have…maybe I’m a little more in tune with my body, and, you know, any symptoms or nonsymptoms…you know, maybe I’m a little more cautious. (Female, 64 years old, LDLR result)

These results also prompted participants to reevaluate priorities in other areas of their life, such as organizing their personal documents or creating a will.

For some participants (n = 12), the result confirmed a diagnosis that they knew ran in their families. These individuals often attributed great personal value to understanding why their family was affected. Many participants (n = 18) also described that their result satisfied their curiosity or was interesting, even if it did not have strong implications for their health.

I’d say that my…I’m drawn in a positive way because it’s just very interesting to find out what is going on in the world you’re living in, that you’re living with all this genetic stuff and also very interesting to find out something about me as an individual. (Female, 69 years old, MYH7 result)

Practical preferences for return of results

Participants generally reported a positive response (n = 27) to the process of receiving results. Most participants felt they received sufficient information and found the discussion of their results to be thorough. Participants were split on the value of receiving their results in person. Some participants felt the in-person session reassured them that they had the undivided attention of the providers delivering the results, and that they benefitted from both observing the nonverbal cues of the providers and having their own nonverbal cues visible as well. Other participants said that the in-person visit was inconvenient and called for greater flexibility in the process.

The most commonly mentioned negative process was the phone call used to query participants about their desire to receive the result. Participants stated that they wanted more reassurance in this call and that it provoked worry, especially since there was often a waiting period between the phone call and result session to allow for CLIA confirmation of the result.

Most participants (n = 25) expressed a strong desire to receive all future results. Some participants commented that the receipt of this result influenced their desire to receive future results, generally affirming their intentions to receive results.

Oh, for sure, yeah. Now that I know that I can take it, you know. I feel pretty confident if I hear about something else I won’t feel scared. (Female, 57 years old, MSH6 result)

Discussion

One of the main factors that is considered when developing result-return guidelines is the potential for the results to have medical benefits for the participant and their family. The majority of participants in this study shared their testing result with at least one health-care provider, which is similar to disclosure rates of BRCA1 results to primary care physicians.20,21 These high disclosure rates are also consistent with participants’ stated intentions to use their individual testing results to engage in preventive health behaviors.6

Disclosure of actionable genetic testing results is desirable because primary care physicians are responsible for coordinating ongoing screening and, in some cases, treatment for the conditions in question. In addition, physician recommendations for health screenings, such as mammography, have been associated with increased patient use of those screenings.22 A modest number of participants noticed changes to their health care after receiving their result, suggesting that their risk for these conditions had not been identified through other means, such as review of their personal or family history. This is similar to previous findings in our cohort23 and points to the potential for sequencing to identify risks that family history may not.

Many individuals described the importance of receiving information in simple terms for sharing the result with family members. When information was conveyed in simple terms, participants reported feeling more confident in their ability to communicate it to family members. This is consistent with previous research on factors influencing communication of genetic risk, which found that unclear or uncertain results were less likely to be communicated.24 Although participants reported valuing a discussion with a health-care provider, it is also possible that receiving results with clear health implications through an interactive platform would be acceptable as long as the information was easy to understand. The high rates of disclosure are consistent with the stated intentions of our participants to use their results to better the health of their family members12; they also provide support for the notion that participants understood the implications of their results for their family members.

Regardless of whether participants experienced changes to their clinical care, many reported that their result had personal utility. These participants’ experiences of deriving personal utility from receipt of a result are consistent with our prior findings and those described in a hypothetical study.6,25 Bunnik et al.11 provide a framework for categorizing elements of personal utility into either a health-care or consumer perspective. The aspects of personal utility most often mentioned by this cohort fit within the health-care perspective, including greater awareness about health in general, reevaluation of personal health behaviors, and making practical preparations for the future. These outcomes may lead to general health benefits if an individual becomes more engaged with their health care as a result of their testing. Less commonly, participants mentioned outcomes that fell into the consumer perspective of personal utility, such as satisfying curiosity or the inherent value of knowing the information. A deeper understanding of what personal utility participants derive from receiving their sequence results would be helpful in defining the construct.

Several publications have outlined concerns that the return of individual results may provoke negative emotional reactions.26,27 However, previous studies of individuals receiving direct-to-consumer genetic profiles,7 genome sequencing,28 and APOE genetic testing for Alzheimer disease susceptibility29 found that adverse psychological outcomes are rare. Similarly, the participants in this study reported largely positive or neutral emotional reactions to their results and described several factors that influenced their response, including their family history, personal history, and age. These factors merit additional research as potential predictors of positive affective outcomes. The factors that influence affective outcomes could be important to assess during the consent process because they could be used to contextualize results in a way that would facilitate coping. They may also help distinguish patients who would most benefit from genetic counseling. However, our findings of low levels of concern and no discernible distress suggest that adverse psychological reactions to results may be minimal, similar to what has been found in other genetic testing settings.7,30 Finally, these data provide evidence that receiving a result does not diminish participants’ enthusiasm to receive future results.

These results also provide additional evidence to inform the practice of returning sequencing results to participants. ClinSeq participants have expressed openness to receiving results through a variety of mechanisms as long as the disclosure process minimizes lag time between being offered the result and receiving it.6 For participants in this study, the telephone call and ensuing wait to receive results were the most negative parts of the process, which reaffirms the importance of expediency in disclosure protocols. This may be a uniquely important consideration in the return of sequencing results since participants do not have prior knowledge of what condition they may be at risk for and therefore experience greater uncertainty when faced with a pending result. If these findings are replicated in larger quantitative studies, they have implications for the design of result disclosure protocols, both in terms of the need for efficiency and for the potential to study interventions designed to manage uncertainty.

This study has several limitations. The participants in this study were well educated, predominantly white, older than reproductive age, and are early adopters of genome sequencing. As such, our findings may not describe the experiences of others seeking return of their results from genome sequencing. We are currently repeating this study using a cohort that has distinct sociodemographic attributes, which will contribute to our understanding of the experiences of those receiving unexpected medically actionable results from genome sequencing. Given the qualitative design of the study, findings are not expected to be generalizable, but rather to generate hypotheses to be tested in larger populations. While we noted no differences, the exploratory design of this study and small number of those receiving results by telephone (n = 2) preclude us from determining whether there were differences in outcomes between those who received results via telephone and those who received them in person. We did not ask about relatives’ health behaviors and may have missed further use of results in families. We are collecting these data longitudinally to report in the future. In addition, these individuals self-selected to participate in genome sequencing and therefore may be more interested in learning their results or more motivated to act on them than other cohorts.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the majority of these participants had a positive or neutral emotional response to the results and experienced very little distress. Yet participants were motivated to communicate their results to health-care providers and family members, which suggests an understanding of their results and their implications for others. These responses are consistent with participants’ stated intentions to use individual results for the improvement of personal and family members’ health status. Taken together, these findings may indicate that providers whose patients receive results in a research setting should be less concerned with the potential for distress and instead attend to motivating patients to follow their medical recommendations.

Disclosure

L.G.B. is an uncompensated adviser to Illumina and receives royalties from the Genentech Corporation. NextGxDx currently employs G.W.H., but the company did not have any role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Shalowitz DI, Miller FG. Disclosing individual results of clinical research: implications of respect for participants. JAMA 2005;294:737–740.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:219–48, 211.

Clayton EW, Ross LF. Implications of disclosing individual results of clinical research. JAMA 2006;295:37; author reply 37–38.

Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3:574–580.

Henderson GE, Wolf SM, Kuczynski KJ, et al. The challenge of informed consent and return of results in translational genomics: empirical analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2014;42:344–355.

Wright MF, Lewis KL, Fisher TC, et al. Preferences for results delivery from exome sequencing/genome sequencing. Genet Med 2014;16:442–447.

Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med 2011;364:524–534.

Sie AS, Prins JB, van Zelst-Stams WA, Veltman JA, Feenstra I, Hoogerbrugge N. Patient experiences with gene panels based on exome sequencing in clinical diagnostics: high acceptance and low distress. Clin Genet 2015;87:319–326.

Collins FS. Exceptional opportunities in medical science: a view from the National Institutes of Health. JAMA 2015;313:131–132.

Foster MW, Mulvihill JJ, Sharp RR. Evaluating the utility of personal genomic information. Genet Med 2009;11:570–574.

Bunnik EM, Janssens AC, Schermer MH. Personal utility in genomic testing: is there such a thing? J Med Ethics 2015;41:322–326.

Facio FM, Brooks S, Loewenstein J, Green S, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Motivators for participation in a whole-genome sequencing study: implications for translational genomics research. Eur J Hum Genet 2011;19:1213–1217.

Bollinger JM, Scott J, Dvoskin R, Kaufman D. Public preferences regarding the return of individual genetic research results: findings from a qualitative focus group study. Genet Med 2012;14:451–457.

Kohane IS, Taylor PL. Multidimensional results reporting to participants in genomic studies: getting it right. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:37cm19.

Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res 2009;19:1665–1674.

Ng D, Johnston JJ, Teer JK, et al.; NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (NISC) Comparative Sequencing Program. Interpreting secondary cardiac disease variants in an exome cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013;6:337–346.

Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol 2002;21:564–572.

Lewis KL, Han PK, Hooker GW, Klein WM, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Characterizing Participants in the ClinSeq Genome Sequencing Cohort as Early Adopters of a New Health Technology. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132690.

Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al.; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013;15:565–574.

Kinney AY, Simonsen SE, Baty BJ, Mandal D, Neuhausen SL, Seggar K, et al. Risk reduction behaviors and provider communication following genetic counseling and BRCA1 mutation testing in an African American kindred. J Genet Couns 2006;15:293–305.

Botkin JR, Smith KR, Croyle RT, et al. Genetic testing for a BRCA1 mutation: prophylactic surgery and screening behavior in women 2 years post testing. Am J Med Genet A 2003;118A:201–209.

The National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? Results of the NCI breast cancer screening consortium and National Health Interview Survey Studies. JAMA 1990;264:54–58.

Johnston JJ, Rubinstein WS, Facio FM, et al. Secondary variants in individuals undergoing exome sequencing: screening of 572 individuals identifies high-penetrance mutations in cancer-susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:97–108.

Forrest K, Simpson SA, Wilson BJ, et al. To tell or not to tell: barriers and facilitators in family communication about genetic risk. Clin Genet 2003;64:317–326.

Henderson G, Garrett J, Bussey-Jones J, Moloney ME, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith G. Great expectations: views of genetic research participants regarding current and future genetic studies. Genet Med 2008;10:193–200.

Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, et al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med 2013;15:258–267.

Yu JH, Harrell TM, Jamal SM, Tabor HK, Bamshad MJ. Attitudes of genetics professionals toward the return of incidental results from exome and whole-genome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet 2014;95:77–84.

Sanderson SC, Linderman MD, Kasarskis A, et al. Informed decision-making among students analyzing their personal genomes on a whole genome sequencing course: a longitudinal cohort study. Genome Med 2013;5:113.

Roberts JS, Christensen KD, Green RC. Using Alzheimer’s disease as a model for genetic risk disclosure: implications for personal genomics. Clin Genet 2011;80:407–414.

Heshka JT, Palleschi C, Howley H, Wilson B, Wells PS. A systematic review of perceived risks, psychological and behavioral impacts of genetic testing. Genet Med 2008;10:19–32.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Flavia Facio for her input on preliminary drafts of the interview guide, Taylor Montminy for her help recruiting participants, and the ClinSeq participants for their time and participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1

(DOC 94 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, K., Hooker, G., Connors, P. et al. Participant use and communication of findings from exome sequencing: a mixed-methods study. Genet Med 18, 577–583 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.133

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.133

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Behavioral and psychological impact of genome sequencing: a pilot randomized trial of primary care and cardiology patients

npj Genomic Medicine (2021)

-

Secondary findings in inherited heart conditions: a genotype-first feasibility study to assess phenotype, behavioural and psychosocial outcomes

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

The Feelings About genomiC Testing Results (FACToR) Questionnaire: Development and Preliminary Validation

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2019)

-

Clinical providers’ experiences with returning results from genomic sequencing: an interview study

BMC Medical Genomics (2018)

-

Distress, uncertainty, and positive experiences associated with receiving information on personal genomic risk of melanoma

European Journal of Human Genetics (2018)