Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to assess whether differences in frequency and phenotype of APC and MUTYH mutations exist among racially/ethnically diverse populations.

Methods:

We studied 6,169 individuals with a personal and/or family history of colorectal cancer (CRC) and polyps. APC testing involved full sequencing/large rearrangement analysis (FS/LRA); MUTYH involved “panel testing” (for Y165C, G382D mutations) or FS/LRA performed by Myriad Genetics, a commercial laboratory. Subjects were identified as Caucasian, Asian, African American (AA), or other. Statistical tests included χ2, Fisher’s exact test, analysis of variance, and z approximation.

Results:

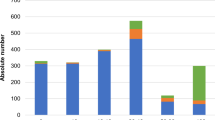

Among participants, 17.5% had pathogenic APC mutations and 4.8% were biallelic MUTYH carriers. With regard to race/ethnicity, 18% were non-Caucasian, with >100 adenomas and younger ages at adenoma or CRC diagnosis (P < 0.0001) than Caucasians. The overall APC mutation rate was higher in Asians, AAs, and others as compared with Caucasians (25.2, 30.9, 24, and 15.5%, respectively; P < 0.0001) but was similar in all groups when adjusted for polyp burden. More MUTYH biallelic carriers were Caucasian or other than Asian or AA (5, 7, 2.7, and 0.3%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Among Caucasians, 5% were biallelic carriers identified by panel testing versus 2% identified by sequencing/large rearrangement analysis (LRA) (P = 0.002). Among non-Caucasians, 3% undergoing panel testing were biallelic carriers versus 10% identified by sequencing/LRA (P < 0.0002).

Conclusion:

Non-Caucasians undergo genetic testing at more advanced stages of polyposis and/or are younger at CRC/polyp diagnosis. Restricted MUTYH analysis may miss significant numbers of biallelic carriers, particularly in non-Caucasians.

Genet Med 17 10, 815–821.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 5% of colorectal cancers (CRCs) diagnosed annually are attributed to highly penetrant genetic syndromes. Of these, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), an autosomal dominant condition, is associated with the development of hundreds to thousands of adenomas in carriers of germ-line mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Individuals with the classically defined syndrome have an almost 100% lifetime risk of developing CRC in the absence of medical or surgical intervention because colorectal adenomas often develop in the second decade of life and require intensive endoscopic evaluation. Up to 10% of APC gene mutation carriers have a milder presentation referred to as “attenuated” FAP, with fewer than 100 colorectal adenomas that, along with CRC, can manifest at older ages.

However, an APC gene mutation may not be detected in up to 20% of patients with a classic FAP phenotype and up to 90% with an attenuated polyposis phenotype.1 Another form of polyposis, caused by alterations in the MUTYH gene, leads to an entity known as MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP). MAP is an autosomal recessive syndrome most often associated with an attenuated polyposis phenotype and is predominantly caused by two commonly detected missense mutations: Y165C and G382D.2 Patients with attenuated FAP and MAP may have similar clinical features, and the conditions may be indistinguishable. Both cause an increased risk of CRC with few polyps and present at older ages, as compared with the easily recognizable classic polyposis phenotype of FAP.1,3,4,5

The majority of information regarding the genetic epidemiology, phenotypic characteristics, cancer risks, and preventive strategies related to FAP and MAP has been reported from studies involving mostly Caucasian individuals from North America, Western Europe, and/or Australia.6,7,8,9,10 However, data from non-Caucasian individuals of diverse ancestral backgrounds have been limited. The goals of this study were to evaluate and compare the presence of APC and MUTYH mutations and associated phenotypic characteristics among different ethnic and racial groups in a large cohort of subjects in the United States who had undergone genetic testing for these genes through Myriad Genetics Laboratory, a large commercial laboratory in the United States. In addition, we assessed the proportion of gene variants detected in APC and MUTYH and the frequency of MUTYH mutations beyond the known common gene hotspots.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Data for this cross-sectional study were obtained from 8,676 individuals who underwent genetic testing for both the APC and MUTYH mutations between 2004 and 2011.1 Patients were selected for genetic testing by health-care providers because of their personal and/or family history of colorectal polyps and/or CRC. Clinically relevant information related to each subject’s cancer and polyp history, along with family cancer history, was obtained from a test requisition form completed by the provider and submitted, along with the patient’s blood samples, to Myriad Genetics Laboratory. Information included age at testing, personal cancer history, age at cancer diagnosis, adenoma count (options prespecified as 0, 1, 2–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–99, 100–999, and ≥1,000), family history of CRC and polyps (including degree of relation, cancer site, age at diagnoses). Data on ancestry were obtained regarding the following prespecified categories: western/northern European, central/eastern European, Ashkenazi, Latin American/Caribbean, African, Asian, Near/Middle Eastern, Native American, or other ancestry. Only those subjects who reported one ancestry were included. Patients who did not report any ancestry, reported multiple ancestries, or had incomplete polyp and/or CRC information were excluded.

Individuals were classified into the following four racial/ethnic groups: (i) Caucasian (western/northern European, central/eastern European, Ashkenazi ancestry), (ii) Asian, (iii) African American, and (iv) other (Latin American/Caribbean, Near/Middle Eastern, Native American, other). The last category comprised combined groups because of the small sample size in each individual group. We defined these groups as “race/ethnicity” because the information was self-reported and subjects may have responded based on a biological or social context. “Ancestry” and “race” are biological identifications with a particular group and do not necessarily relate to cultural or environmental characteristics, whereas “ethnicity” can relate to cultural identification among individuals who may or may not have a common genetic origin. Therefore, the use of “race/ethnicity” incorporates both a biological and cultural interpretation.

The study was initiated by the investigators. Data collection and statistical analysis occurred independently. The collection of clinical data and molecular analyses occurred at Myriad Genetic Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT). An anonymized data set was provided to the investigators at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Columbia University Medical Center for all data analyses, which were conducted by clinical researchers (J.A.I., F.K.) who are not affiliated with Myriad Genetic Laboratories. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Columbia University Medical Center.

Laboratory methods

As previously described,1 all subjects had undergone APC and MUTYH gene testing. Subjects had full gene sequencing and large rearrangement analysis of the APC gene. Full gene sequence of ~8,532 base pairs comprising 15 exons and 420 adjacent noncoding intronic base pairs was determined in the forward and reverse directions. For large rearrangement analyses, all exons of the APC gene were examined for evidence of deletions and duplications using standard Southern blot methods.

All individuals also underwent DNA sequence analysis of MUTYH, but the mutational analyses performed varied among subjects. The type of MUTYH testing conducted was based on the provider’s specification on the test requisition form. Options included (i) sequencing specific portions of MUTYH designated to detect the two most common mutations (Y165C and G382D), also referred to as “panel testing,” or (ii) full MUTYH gene sequencing without initially restricting DNA mutational analysis to the two most common mutations. When one of the common gene mutations was detected on panel testing, full gene sequencing was conducted reflexively, without the need for a specific request by the provider.

Directed DNA sequence analysis, designed to detect the mutations Y165C and G382D, was performed on exons 7 and 13. Full sequence analysis was performed in both the forward and reverse directions of ~1,608 base pairs comprising 16 exons and ~450 adjacent noncoding intronic base pairs. The noncoding intronic regions of MUTYH that were analyzed do not extend more than 20 base pairs proximal to the 5′ end and 10 base pairs distal to the 3′ end of each exon. Aliquots of patient DNA were each subjected to polymerase chain reaction amplification reactions. The amplified products were each directly sequenced in forward and reverse directions using fluorescent dye–labeled sequencing primers.

Individuals with deleterious or suspected deleterious mutations in either the APC or MUTYH gene were defined as having pathogenic mutations. We report only results of biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers. The presence of recurrent pathogenic mutations among non-Caucasians was evaluated for both genes and, when identified, the presence in Caucasians (whether in this data set and/or reported in the published literature or public databases) also was assessed. Individuals with suspected polymorphisms were defined as having nonpathogenic mutations. Individuals with gene mutations whose association with FAP and MAP disease risk is unknown were defined as having variants of unknown significance (VUSs). DNA mutational analysis techniques did not change during the study period.

Statistical methods

The primary outcome of interest was the frequency of pathogenic APC and MUTYH mutations among the four racial/ethnic groups. Secondary outcomes of interest were a comparison of genotype–phenotype characteristics among gene mutation carriers in the four racial/ethnic groups by assessing adenoma count, age at adenoma diagnosis, personal history of CRC, age at CRC diagnosis, and history of CRC in first-degree relatives. For subjects with adenomas identified more than once, a cumulative adenoma count was computed. Adenoma count was a categorical variable (0, <10, 10–19, 20–99, 100–999, ≥1,000 adenomas). In subjects diagnosed with CRC more than once, the age at diagnosis was defined as the age at first diagnosis. Age was analyzed as a continuous variable. All categorical and binary variables were analyzed by a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test and reported as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All continuous variables were analyzed by analysis of variance and were reported as mean values with SEs and 95% CIs. The z approximation test compared differences between two proportions. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For missing data related to adenoma counts and age at adenoma diagnosis, a multiple imputation approach was used to obtain estimates, as previously reported.1 The coefficients of five rounds of imputation (performed in R software using the ArgeImpute function) were combined to obtain the final estimates for missing data. All other statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Subject characteristics

Data from 8,676 individuals who had undergone genetic testing for both the APC and MUTYH genes were analyzed. Subjects who did not report any race or ethnicity or who provided more than one race or ethnicity were excluded. A total of 6,169 subjects were included; Table 1 provides data on the participants’ characteristics. The majority of subjects (5,041/6,169; 81.7%) were Caucasian; 151 (2.5%) were Asian, 382 (6.2%) were African American, and 595 (9.6%) were of other race/ethnicity. Among all subjects, 5,176 (83.9%) reported a personal history of adenomas, with a mean age of 45 years at the time of first diagnosis. A personal history of CRC was reported by 1,660/6,169 individuals (27%), and the mean age at diagnosis was 46.5 years. The majority of subjects with CRC also reported having adenomas (1,292/1,660; 21%) whereas only 6% of all subjects had CRC but no adenomas. The majority of patients with adenomas had <100 polyps (4,074/5,236; 77.8%). Last, 1,929/6,169 of the subjects (31.3%) reported having a first-degree relative with CRC.

Presence of APC gene mutations and phenotypic characteristics of mutation carriers

More than 17% of subjects (1,081/6,169; 17.5%) were identified as APC mutation carriers ( Table 2 ). Among Caucasians, 782/5,041 (15.5%) had a pathogenic APC mutation detected. The APC mutation rates in the Asian, African-American, and other groups were almost twice the rate among Caucasians (25.2, 30.9, and 24%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Among all APC mutation carriers, there were no significant differences in the phenotypic characteristics between any of the racial/ethnic groups, including number of adenomas, age at adenoma diagnosis, presence of CRC, age at CRC diagnosis, and first-degree relates with CRC (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online). Non-Caucasians reported a personal history of both CRC and adenomas more often than Caucasians (P = 0.05). There was no difference in the frequency of pathogenic APC mutations according to polyp counts between Caucasians and non-Caucasians. There were no recurrent pathogenic APC mutations identified among non-Caucasians that were associated with a particular phenotype. The majority of recurrent mutations identified among non-Caucasian carriers were also seen in Caucasians. Supplementary Table S5 online includes data on recurrent APC gene mutations among non-Caucasian carriers and associated phenotypes.

Of all subjects undergoing APC testing, 6% (399/6,169) were found to have a VUS ( Table 2 ). The highest proportion of VUSs was detected among Asians and African Americans; 11% of Asians and African Americans had a VUS (17/151 and 43/382, respectively) versus 6% for Caucasians and others (303/5,041 and 36/595, respectively; P < 0.0001) ( Table 2 ). The APC I1307K alteration was more prevalent among Caucasians (55/303; 18.5%) versus others (3/36; 8.3%). No APC I1307K alterations were detected among African Americans or Asians.

Presence of MUTYH gene mutations and phenotypic characteristics of mutation carriers

Nearly five percent (298/6,169, 4.8%) of subjects were identified as biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers, and most were Caucasian (250/298; 84%) ( Table 2 ). The prevalence of biallelic MUTYH mutations among all Caucasian subjects was 5% (250/5,041), as compared with 2.7% in Asians (95% CI: 0.7–6.6), 0.3% in African Americans (95% CI: 0.01–1.5), and 7.2% in others (95% CI: 5.3–9.6) (Supplementary Table S1 online). There were no significant phenotypic differences among the biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers when stratified by race/ethnicity (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 online). The majority of MUTYH gene mutation carriers had an attenuated polyposis phenotype with <100 polyps (225/298; 75%), regardless of race/ethnicity. There was no difference in the frequency of biallelic MUTYH mutations according to polyp count between Caucasians and non-Caucasians. Upon review of the mutation spectrum associated with pathogenic MUTYH gene mutations, the E466X mutation was identified solely among Asian individuals. All other recurrent mutations identified among non-Caucasians were also reported in Caucasians.

Of all subjects who underwent genetic testing for MUTYH, 0.9% (55/6,169) were found to have a VUS ( Table 2 ). The highest VUS rates were in Asians (3/151; 2%) and African Americans (12/382; 3.1%), as compared with Caucasians (39/5,041; 0.8%) and others (1/595; 0.2%; P < 0.0001).

DNA mutational analysis for the identification of biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers

Of all subjects undergoing DNA mutational analysis for MUTYH, 89% (5,491/6,169) had panel testing for Y165C and G382D, whereas 11% (678/6,169) had full sequencing/large rearrangement analysis. Of all Caucasians who were identified as biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers, 5% (239/4,526) were identified by panel testing, whereas only 2% (11/515) were identified using full sequencing/large rearrangement analysis (P = 0.002) ( Table 3 ). Of all non-Caucasians who were identified as biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers, only 3% (31/965) were identified by panel testing, whereas 10% (17/163) were identified using full sequencing/large rearrangement analysis (P < 0.0002). Supplementary Table S6 online provides data on recurrent MUTYH gene mutations and associated phenotypes among non-Caucasian carriers.

Clinical characteristics of all subjects undergoing genetic testing, stratified by race or ethnicity

Because there were no differences in the phenotypic characteristics of APC and biallelic MUTYH gene mutation carriers among the four racial/ethnic groups despite variation in the frequency of deleterious mutations, we assessed the eligible subjects’ clinical characteristics at time of genetic testing. An attenuated polyposis phenotype was more prevalent among Caucasians than among non-Caucasians (adenoma count ≤10, 11–19, 20–99; P = 0.15, 0.02, and 0.06, respectively; Table 4 ). Conversely, all non-Caucasian groups had a higher prevalence of the classic polyposis phenotype as compared with Caucasians, with more individuals reporting 100–999 adenomas and ≥1,000 adenomas (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.009, respectively). The mean age at adenoma diagnosis for non-Caucasians was younger than that of Caucasians (43.4 vs. 45.4 years). Specifically, Asians, African Americans, and others had mean ages of 43.5 years (95% CI: 41.2–45.7), 43.9 years (95% CI: 42.5–45.2), and 42.9 years (95% CI: 41.8–44.1), respectively, whereas Caucasians had a mean age of 45.4 years (95% CI: 45–45.76; P < 0.0001).

There were no differences regarding personal history of CRC with or without history of adenomas (P = 0.11 and P = 0.39, respectively) and presence of a first-degree relative with CRC (P = 0.07) between the four racial/ethnic groups ( Table 5 ). Similar to age at adenoma diagnosis, however, the mean age at CRC diagnosis was younger in non-Caucasians than in Caucasians (43.7 vs. 47.3 years); Asians, African Americans, and others were diagnosed at mean ages of 44.8 years (95% CI: 40.7–48.6), 44.6 years (95% CI: 42.0–47.3), and 41.7 years (95% CI: 39.4–44.0), respectively (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

This study is the largest to examine the results of genetic testing for APC and MUTYH gene mutations among individuals from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds with a history of CRC and adenomas. Our initial objective was to determine whether there were differences in disease manifestations among mutation carriers of different ethnicities, which has not been studied extensively thus far. We found no differences in phenotypic characteristics among APC and biallelic MUTYH mutation carriers who were of Caucasian, Asian, African-American, or other race or ethnicity, but, surprisingly, there were significant differences in the frequency of APC and MUTYH gene mutations within these groups. These differences are most likely due to the selection of patients undergoing genetic testing or methods of DNA mutational analyses used, rather than inherent biologic differences between the groups. Overall, non-Caucasian patients more often had a history of colorectal adenomas and/or CRC diagnosed at younger ages and a stronger polyposis phenotype as compared with Caucasians, who were older at the time of adenoma/CRC diagnosis and had an attenuated polyposis phenotype. Because the majority of non-Caucasian subjects undergoing testing had a more severe presentation than Caucasians, it is not surprising that the APC mutation rates in the Asian, African-American, and other patient groups were significantly higher.

Conversely, among individuals with biallelic MUTYH gene mutations, the mutation frequency was significantly higher among Caucasians and others as compared with Asians and African Americans. These results may be attributed to the variable approaches of DNA mutation analyses in the detection of MUTYH gene mutations. In this study, 89% of all subjects tested for MUTYH alterations had analyses limited to the common Y165C and G382D mutations, whereas only 11% of subjects had full sequencing/large rearrangement analysis. The current practice for detecting MUTYH gene mutations begins with analysis of either Y165C or G382D mutations.11 Among Caucasians these missense mutations account for the majority of pathogenic MUTYH mutations detected; up to 93% of biallelic mutation carriers carry at least one of these two “hotspots.”12 However, other mutations may be more frequent in non-Caucasians and potentially missed by restricted mutational analysis. For example, the E466X mutation has been commonly reported in Pakistani or Indian individuals with MAP13 and was a recurrent mutation among the Asian biallelic MUTYH carriers in our study. Although a limited testing strategy may miss deleterious mutations in all patients undergoing MUTYH genetic testing, the impact may be particularly pronounced among non-Caucasians. Among the non-Caucasian biallelic MUTYH gene mutation carriers, 17/48 (35%) would not have been identified if testing had been limited to detection of the two common missense mutations.

In contrast to MAP, FAP has been more extensively studied, and multiple studies have reported the prevalence of APC gene mutations and genotype–phenotype correlations among carriers related to disease severity, age at polyp detection and cancer onset, and the presence of extracolonic manifestations.14,15,16 However, these data have been derived predominantly from Caucasian subjects enrolled in North American, Australian, or European familial cancer registries. Although some studies suggest that the prevalence of certain APC gene mutations may vary worldwide17,18,19 and that some ethnic variation in the clinical presentation of FAP may exist,20 results have been inconsistent and limited by the small patient populations assessed. The results of our study do not support the existence of any phenotypic differences between APC gene mutation carriers of different races and ethnicities. We also did not identify any specific recurrent mutations among non-Caucasians to be associated with a particular phenotype.

Highly penetrant polyposis syndromes are easily recognized and are likely to prompt genetic evaluation. A more subtle presentation, such as that associated with attenuated polyposis, may be less recognized, and the opportunity to refer patients for genetic evaluation may be missed. Individuals with 10 or more cumulative adenomas should be considered for genetic evaluation and testing for germ-line APC or MUTYH mutations,21 as supported by recent evidence that an increasing number of adenomas, as well as young age at adenoma onset, are strong predictors of carrying a deleterious APC or MUTYH gene mutation.1 However, studies report that physicians who care predominantly for non-Caucasian patients are less likely to order genetic testing or recommend genetic evaluation and counseling.22 Although our study cannot address why non-Caucasian patients with polyposis less often undergo genetic testing, we speculate that a number of issues may exist beyond the health-care providers’ lack of referral. Patients may not appreciate the benefits of genetic testing for attenuated polyposis because the burden of disease among family members may be less apparent and perception of inherited CRC risk and acceptance of genetic testing may be different between different ethnic/racial groups. Studies have shown that African Americans and Hispanics are less knowledgeable about genetic testing for certain diseases as compared with Caucasians, and African Americans are less confident in the benefits of genetic testing.23,24,25 There may also be significant differences in insurance coverage of genetic testing for individuals with an attenuated polyposis phenotype, which may have a more substantial negative impact on individuals of lower socioeconomic status and/or underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds.26 These issues were beyond the scope of our study and may be areas for future research.

Our study has a number of important strengths. It represents a nationwide sample of patients diagnosed with CRC and/or adenomas undergoing genetic testing and is the largest cohort of APC and MUTYH mutation carriers studied to date. It includes a diverse population from different ethnic and racial backgrounds and allows us to explore the impact of variable genetic testing approaches in different populations, particularly for the detection of MUTYH alterations. We were able to examine differences in the spectrum of APC and MUTYH mutations in different racial/ethnic groups, in particular the frequency of VUS. We found a higher detection rate of VUS for both genes among non-Caucasians. The rate of VUS detected in the APC gene among Asians and African Americans was nearly double that of Caucasians and individuals of other race or ethnicity. Although the overall frequency of VUS was much lower in the MUTYH gene (0.9%), the pattern was similar to that of APC VUS among the different groups. Although the current methods used to classify VUS are complex, studies that include racially and ethnically diverse populations are necessary.

There are also a number of potential limitations related to this study. Misclassification of race and ethnicity may have been possible because this information was gathered by self-report, and subjects were required to answer based on predefined categories. In an attempt to minimize misclassification, eligibility was limited to only those subjects who reported one race/ethnicity. A more updated race and ethnicity classification system, such as the one currently supported by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in clinical trials (which combines both race and ethnicity in each predefined category), would have been preferred and should be considered for future studies. In addition, the data were provided by a single commercial laboratory and rely on clinical information reported on the mandatory test requisition form, where verification of diagnoses and collection of additional data were not possible. Although reporting errors may occur, the fact that health-care professionals are the sources of data likely minimizes those based on incorrect diagnoses, and results using similar data sets have been validated using external data from familial cancer registries.27,28 Last, the overall prevalence of biallelic MUTYH gene mutation carriers is low, even more so for non-Caucasian patients, despite the large number of patients undergoing testing for CRC and polyposis. This may limit our interpretation of results pertaining to genotype–phenotype correlations among non-Caucasian individuals with MUTYH gene mutations.

In summary, the results of this study provide new insight into the current practices and patterns of predictive testing for APC and MUTHY mutations among a large, racially and ethnically diverse population undergoing genetic testing for colorectal adenomas and CRC in the United States. High detection rates of APC mutations among non-Caucasians of Asian and African descent likely relate to testing patients with a severe clinical presentation of classic polyposis and onset of CRC at a young age than individuals with an attenuated polyposis phenotype. Conversely, fewer MUTYH gene mutations were detected among non-Caucasians; this likely relates to the decreased uptake of full gene sequencing for MUTYH in cases in which selective DNA mutational analysis may miss pathogenic MUTYH mutations among these patients. Additional studies that examine the contribution of race/ethnicity to the genetic epidemiology related to inherited CRC syndromes are needed, as are studies of the possible barriers related to genetic testing for cancer susceptibility among diverse patient populations.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Grover S, Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas. JAMA 2012;308:485–492.

Sampson JR, Jones N . MUTYH-associated polyposis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2009;23:209–218.

Russell AM, Zhang J, Luz J, et al. Prevalence of MYH germline mutations in Swiss APC mutation-negative polyposis patients. Int J Cancer 2006;118:1937–1940.

Renkonen ET, Nieminen P, Abdel-Rahman WM, et al. Adenomatous polyposis families that screen APC mutation-negative by conventional methods are genetically heterogeneous. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5651–5659.

Jenkins MA, Croitoru ME, Monga N, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in monoallelic and biallelic carriers of MYH mutations: a population-based case-family study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:312–314.

Aceto G, Curia MC, Veschi S, et al. Mutations of APC and MYH in unrelated Italian patients with adenomatous polyposis coli. Hum Mutat 2005;26:394.

Enholm S, Hienonen T, Suomalainen A, et al. Proportion and phenotype of MYH-associated colorectal neoplasia in a population-based series of Finnish colorectal cancer patients. Am J Pathol 2003;163:827–832.

Gismondi V, Meta M, Bonelli L, et al. Prevalence of the Y165C, G382D and 1395delGGA germline mutations of the MYH gene in Italian patients with adenomatous polyposis coli and colorectal adenomas. Int J Cancer 2004;109:680–684.

Isidro G, Laranjeira F, Pires A, et al. Germline MUTYH (MYH) mutations in Portuguese individuals with multiple colorectal adenomas. Hum Mutat 2004;24:353–354.

Vandrovcová J, Stekrová J, Kebrdlová V, Kohoutová M . Molecular analysis of the APC and MYH genes in Czech families affected by FAP or multiple adenomas: 13 novel mutations. Hum Mutat 2004;23:397.

Goodenberger M, Lindor NM . Lynch syndrome and MYH-associated polyposis: review and testing strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:488–500.

Sampson JR, Dolwani S, Jones S, et al. Autosomal recessive colorectal adenomatous polyposis due to inherited mutations of MYH. Lancet 2003;362:39–41.

Dolwani S, Williams GT, West KP, et al. Analysis of inherited MYH/(MutYH) mutations in British Asian patients with colorectal cancer. Gut 2007;56:593.

Järvinen HJ, Peltomäki P . The complex genotype-phenotype relationship in familial adenomatous polyposis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:5–8.

Giardiello FM, Krush AJ, Petersen GM, et al. Phenotypic variability of familial adenomatous polyposis in 11 unrelated families with identical APC gene mutation. Gastroenterology 1994;106:1542–1547.

Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF . Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;61:153–161.

Schnitzler M, Koorey D, Dwight T, et al. Frequency of codon 1061 and codon 1309 APC mutations in Australian familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Hum Mutat 1998(suppl 1):S56–S57.

Gavert N, Yaron Y, Naiman T, et al. Molecular analysis of the APC gene in 71 Israeli families: 17 novel mutations. Hum Mutat 2002;19:664.

Cao X, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F, Zao Y, Cheah PY . APC mutation and phenotypic spectrum of Singapore familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2000;8:42–48.

Han SH, Ryu JS, Kim YJ, Cho HI, Yang YH, Lee KR . Mutation analysis of the APC gene in unrelated Korean patients with FAP: four novel mutations with unusual phenotype. Fam Cancer 2011;10:21–26.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colorectal Cancer Screening (2.2013). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colorectal_screening.pdf. Accessed 13 January 2014.

Shields AE, Burke W, Levy DE . Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: results of a national survey. Genet Med 2008;10:404–414.

Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M . Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. JAMA 2005;293:1729–1736.

Peters N, Rose A, Armstrong K . The association between race and attitudes about predictive genetic testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:361–365.

Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, Wicklund CA . Awareness and attitudes regarding prenatal testing among Texas women of childbearing age. J Genet Couns 2007;16:655–661.

Suther S, Kiros GE . Barriers to the use of genetic testing: a study of racial and ethnic disparities. Genet Med 2009;11:655–662.

Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, Balmaña J, et al.; Colon Cancer Family Registry. Comparison of the clinical prediction model PREMM(1,2,6) and molecular testing for the systematic identification of Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer. Gut 2013;62:272–279.

Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, Mercado R, et al. The PREMM(1,2,6) model predicts risk of MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 germline mutations based on cancer history. Gastroenterology 2011;140:73–81.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lynn Ann Burbidge and Richard J. Wenstrup of Myriad Genetics Laboratories for their assistance in data retrieval and preparation. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grants K07 CA151769 (F.K.) and K24113433 (S.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

(DOC 274 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Inra, J., Steyerberg, E., Grover, S. et al. Racial variation in frequency and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in 6,169 individuals undergoing genetic testing. Genet Med 17, 815–821 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.199

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2014.199