Abstract

Cystic fibrosis is the most common severe autosomal recessive disease, with a prevalence of 1 in 2,500–3,500 live births and a carrier frequency of 1 in 25 among Northern Europeans. Population-based carrier screening for cystic fibrosis has been possible since CFTR, the disease-causing gene, was identified in 1989. This review provides a systematic evaluation of the literature from the past 23 years on population-based carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, focusing on the following: uptake of testing; how to offer screening; attitudes, opinions, and knowledge; factors influencing decision making; and follow-up after screening. Recommendations are given for the implementation and evaluation of future carrier-screening programs.

Genet Med 2014:16(3):207–216

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It has been 23 years since the discovery of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene in 1989, which made carrier screening for cystic fibrosis (CF) possible.1 CF is the most common severe autosomal recessive condition in those of Northern European ancestry, with a prevalence of 1 in 2,500–3,500 live births and a carrier frequency of 1 in 25.2 Mutations in the CFTR gene result in reduced or absent CFTR channel function in the epithelial cells of the lungs, pancreas, liver, sweat ducts, male reproductive tract, and digestive tract.2 More than 1,900 gene alterations have been identified, with p.F508del being the most frequently occurring mutation in the Northern European population, accounting for ~70% of all mutations present.2

Chronic suppurative lung disease is the most severe feature of CF and is largely responsible for the reduced life expectancy. There is currently no cure for CF, and the median survival time is 37 years.3 Treatment involves daily chest physiotherapy, regular antibiotics, pancreatic enzyme replacement, vitamin and salt replacement, and a controlled diet.4 Lung transplantation is possible, although the 6-year survival rate after transplantation is 50%.2 Diagnosis of CF by newborn screening (NBS) is routine in many European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, and New Zealand.5 Parents of children diagnosed with CF through NBS are identified as carrier couples. In Victoria, Australia, most carrier couples identified through NBS in 1990–1995 had no further children or used prenatal diagnosis for subsequent pregnancies.6

Carrier couples may also be identified through population-based CF carrier screening, the aim of which is to offer testing to as many individuals as possible regardless of family history. In the United States, guidelines recommend that CF carrier screening be offered to all pregnant women and couples planning a pregnancy.7 In Australia there have been similar recommendations.8 In the United Kingdom, Canada, and France, population-based CF carrier screening is not currently recommended and is generally offered only to those who have a family history of CF and to partners of individuals with CF. The UK National Screening Committee is currently reviewing its policy on screening for CF carrier status during pregnancy.9

Some major issues regarding implementation of routine CF carrier screening in the general population include the following: accessibility; how best to provide education and counseling; perceived relevance in the absence of a family history; carrier detection rate, including residual risk due to the fact that screening is less than 100% sensitive; and the psychological impact of being found to be a carrier.

Therefore, it is timely to review the available evidence on population-based CF carrier screening. This review provides a systematic evaluation of the literature from the past 23 years.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched (latest search date: 31 October 2012): Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; 1950–present), Embase (Excerpta Medica Database; 1980–present), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsychINFO, and the Cochrane Library. A detailed search strategy for each database is available from the authors upon request.

Search terms were key words and relevant medical subject headings for CF, genetic carrier testing, or screening. Search terms, combined with the term “cystic fibrosis,” were the following: carrier testing, heterozygote detection, screening, genetic research, medical genetics, population genetics, pregnancy, prenatal diagnosis, preconception care, behavior, psychological processes, attitude to health, genetic counseling, and genetic risk. Reference lists of identified studies were examined, and citations were tracked for any potentially relevant additional studies. The search outputs were managed using Endnote (version X).

Criteria for inclusion

The focus of this article was peer-reviewed original research in which participants were offered CF carrier screening or were asked to consider a hypothetical offer of screening, or their views on CF carrier screening were sought.

The areas reviewed were the following:

-

1

Attitudes to screening: studies assessing attitudes of participants/potential participants, formally or informally, toward population-based screening for CF.

-

2

How to offer screening: studies exploring the method of offering CF carrier screening.

-

3

Uptake of screening: studies measuring the number of individuals/couples who accepted or declined an offer of CF carrier screening.

-

4

Factors influencing decisions about screening: studies determining barriers and facilitators with regard to undergoing CF carrier screening.

-

5

Knowledge: studies reporting knowledge of CF and genetic screening at any point before, during, or after the screening process.

-

6

Outcomes and follow-up of screening for CF carrier status: studies reporting outcomes of screening in terms of recalling/understanding carrier status, screening of partner, current/future reproductive behavior, and dissemination of information to family members.

-

7

Psychological factors: studies exploring psychological effects on participants involved in screening for CF carrier status.

Key findings of the studies and experiences are described in this review.

Criteria for exclusion from review

Non–English language articles and studies not generating any original research data, such as editorials, opinions, commentaries, and reviews, were excluded from the review. Studies in which diagnostic testing such as NBS, as opposed to carrier testing, was conducted and studies focusing on laboratory aspects of screening, rather than clinical aspects, were also excluded.

Assessment for potential inclusion of studies

Three reviewers (B.J.M., L.I., and L.F.) independently assessed the studies based on both title and abstracts for inclusion or exclusion according to the criteria outlined above. Another reviewer (S.A.M.) was available to resolve any potential differences.

Data extraction

Data collected from the studies included name of first author, year, title, country, aim/hypothesis of study, participant characteristics, study design, sample size, measures used, key results, and conclusions.

Data analysis

Analysis of categorical variables was undertaken using χ2 analyses. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the studies.

Results

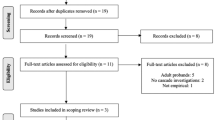

The search yielded 15,982 references and, after duplicates were removed, 14,761 studies remained. A total of 85 references met the inclusion criteria for data extraction ( Figure 1 ; Table 1 ; see Supplementary Material online).

All the studies were published after 1989: 31 (37%) were from the United Kingdom, 21 (25%) were from the United States, and eight (9%) were from Australia. Sixty-four (75%) articles involved actually offering CF screening, with 34 (40%) focusing on prenatal screening and 26 (31%) on preconception screening. The remaining 25 (29%) offered CF screening to the general population regardless of pregnancy status ( Table 1 ). Due to the heterogeneity of the samples in the studies, this review will use the term “target population” as a collective term to refer to the participants included in each study. These participants may be couples and individuals being offered screening (or asked to consider a hypothetical offer of screening) in a prenatal setting (or before conception) or may be members of the general population including settings such as high schools or colleges. The various settings for each study are described in further detail in the Supplementary Material online.

During data extraction, the studies were coded into the seven areas of interest, with some covering multiple areas ( Table 2 ). The number of papers was spread relatively evenly across these areas. The highest number of articles (n = 40) reported “uptake” (47%), and the least number of studies (n = 17) evaluated “how to offer” screening (20%).

When comparing studies that offered screening and those in which screening was hypothetical, studies in which screening was offered were more likely to measure knowledge (χ2 = 24.79, P < 0.01); outcomes and follow-up of screening (χ2 = 15.77, P < 0.01); and psychological factors associated with screening (χ2 = 10.35, P < 0.01).

Please refer to the Supplementary Material online for information on each of the studies included in the review. The Supplementary Material provided includes the following: first author; year; country where the study was conducted; the setting in which testing was offered; study design; whether testing was offered or hypothetical; and uptake rates of testing, if measured.

Attitudes toward CF carrier screening

Assessing attitudes of the target population toward population-based CF carrier screening can inform likely interest in and uptake of screening. In the general population, 60–100% believed screening for CF carrier status should be made available,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and 80–96% felt it should be routinely offered.17,18,19 However, some reservations were reported about the widespread offer of screening and its perceived systematic implementation by governments.10,14 The best time to offer screening was believed to be to individuals of reproductive age, before pregnancy, or when planning a pregnancy.10,11,12,20 The general population believed results of screening would influence their reproductive decisions.10,21,22 Interest in screening was high, with 54–80% of the general population showing interested,19,22,23,24 although interest differed depending on life stage, with those of reproductive age showing more interest than those who had finished or were yet to start their families.19,24,25

Population-based CF carrier screening can be implemented at various life stages, including the neonatal stage, high school and college age, reproductive age, when planning a family, or during the early stages of pregnancy. The majority of studies in which attitudes were measured showed that individuals of high school and college age had positive attitudes toward screening for CF,19,26,27,28 with 86–96% believing such screening should be available19,28,29 and 40–59% stating that the best time to offer screening is before pregnancy.27,28 However, most studies showed that the majority of those questioned did not want to have screening while at school.19,24,27

Nonpregnant women and couples planning a pregnancy had positive attitudes,30,31,32,33,34 with 69–89% believing that CF carrier screening should be routinely offered to all couples planning a pregnancy.30,32,33,34 Pregnant women had similar attitudes toward screening.35,36,37,38,39 Ninety-eight percent of pregnant women believed that the best time to offer screening is before pregnancy.23 Nevertheless, 69% indicated they would accept an offer of screening during pregnancy, and 67% said they would utilize prenatal diagnosis.23 Attitudes of pregnant women toward screening have been shown to be influenced by perceived susceptibility, in addition to barriers to and benefits of screening, with barriers having the most negative impact on attitudes.40

How to offer CF carrier screening

Determining the most effective approach to both providing information and offering screening is essential to ensure maximum opportunity for participation and informed decision making.

Between 50 and 94% of the target population preferred to receive an offer of CF carrier screening, pretest information, and counseling from a general practitioner.12,15,24,37,41 A consultation with a general practitioner resulted in higher uptake of screening: 25% uptake in couples planning a pregnancy, as compared with only 9–12% uptake when invited to attend a dedicated group information session.33,34

When exploring the method of offering testing, 39–70% of the target population preferred to be offered testing in person rather than receiving the offer via a letter or brochure.42,43 How information is provided has been explored, with 77–96% reporting brochures/information leaflets as useful.14,21,41,44,45 The main information that potential participants wanted to receive was information about CF and screening, in particular, the risk of being a carrier and having a child with CF.46

Written and audiovisual information were found to be equally effective.47 There was no difference in knowledge for those who received pretest information from an interactive computer program as compared with those attending a genetic counseling session.48 However, one study showed that presenting a videotape in addition to a leaflet resulted in significantly higher knowledge than when only a leaflet was provided.39

Uptake of CF carrier screening

Uptake was reported as the percentage of individuals/couples who accepted an offer of CF carrier screening of the total number of individuals/couples offered. Uptake ranged from 46 to 99.8% in the prenatal setting, 2–96% in the preconception setting, and 8–17% in the general population ( Table 3 ).

Uptake was higher in women as compared with that in men,49,50 and the screening approach—whether couples were screened as a unit (couple screening) or individually (stepwise screening)—did not influence uptake.51,52

Factors influencing decisions about CF carrier screening

Factors that influence the decision to accept or decline an offer of CF carrier screening have been explored in various studies. Gender, ethnicity, parity, future reproductive plans, income, and level of education were all factors that influenced the decisions regarding CF carrier screening. Affluent Caucasian women with high education who had no children and were planning future pregnancies were most likely to accept an offer of screening.43,53,54,55 Life stage was also shown to be important in decisions about screening, with studies showing lower interest from preconceptional individuals as compared with those already pregnant.14,15 Although a study exploring the decision-making process of pregnant women regarding an offer of screening concluded that pregnancy is not the best time for informed decision making, pregnancy had a powerful influence on the decision-making process.56

The main factors that arose when exploring the reasons for accepting and declining an offer of screening are shown in Table 4 . Other factors that influenced the decision to accept screening were ease of test procedure; individuals’ feelings that they could not refuse the offer; individuals’ feelings that they would regret not undergoing screening; perceived importance of the test; perceived positive consequences; perceived fewer barriers; and perceived less difficulty in informing relatives.30,57,58 Other factors that influenced the decision to decline an offer of screening were concern about test sensitivity; not wishing to be tested during pregnancy; not wanting to know; insurability; limited knowledge; the requirement of a blood test; and religious beliefs.15,31,59

Knowledge of CF and genetic screening

Evaluating knowledge of CF and CF carrier screening can assess individuals’/couples’ informed decision making in the context of accepting or declining such an offer. Knowledge has been tested at various points during the screening process: before receiving information, after receiving information, and after receiving test results. Testing knowledge before receiving information is indicative of the general knowledge held by the population. Many studies have shown that initial knowledge of CF and CF carrier screening is low,10,12,21,22,24,28,29,60,61 with gender and education significantly influencing knowledge level:12,47,62 well-educated women had higher knowledge scores. Secondary and tertiary students tended to have a higher level of knowledge as compared with those in the general population.27,28,29,63 In general, the studies showed that participants were unaware that CF is an inherited condition,12,21,24,57 did not know that CF affected the lungs,10,12,61 were unaware that the majority of carriers do not have a family history of CF,16,21,61 and thought carriers had symptoms of the disease.61 Knowledge levels increased after receiving information on CF and screening.28,29,58,60,62 One study found that those who declined screening had a lower level of knowledge than those who accepted.32

Evaluation of knowledge after receiving the test result has shown that carriers of CF had a higher level of knowledge as compared with noncarriers.20,42,58,64 Knowledge decreased with the time elapsed since the test,64 although this may be the case only for noncarriers, with no decrease in knowledge observed for carriers 3 months after testing.58

The majority of those screened did not understand the concept of residual risk for future pregnancies, believing that a negative test result meant they had no chance of having a child with CF.48,63,64,65,66,67,68 Although the majority of noncarriers understood the meaning of their carrier status, some believed that they were definitely not a carrier,20,42,47,50,52,53,57,69,70,71,72,73,74 and some carriers believed they had no risk of having a child with CF due to their partner’s negative test result.58,74 The confusion regarding residual risk may have implications for a carrier if he or she is to change partners in the future.

Outcomes and follow-up of screening for CF carrier status

Studies involving the follow-up of CF carrier screening were undertaken at various time points ranging from 2 weeks to 3 years after testing; these explored recollection and understanding of carrier status, testing of partners, impact on current and future reproductive plans, and the dissemination of information to other family members. The majority of carriers and noncarriers correctly recalled their carrier status,47,52,64,71,74,75 with carriers more frequently recalling their carrier status as compared with noncarriers.20,53,67,73,76 Nevertheless, some carriers believed they were only likely to be carriers of CF.42,50,53,64,73

Individual carrier status did not affect reproductive intentions or behaviors, with carriers not altering their reproductive plans after receiving a positive test result.65,66,67,71,73,76,77,78 Screening of partners of carriers to determine risk of having a child with CF had an uptake of 61–100%,20,36,52,74,78,79,80,81,82,83 with reasons for partners not being tested being as follows: anxiety about result; would be tested when planning to start a family; would not alter reproductive plans; and had no further reproductive plans.74,78 When participants were asked to consider their reproductive intentions if they were found to be a carrier couple, the majority stated that they would not have (more) children,10,71 would utilize prenatal diagnosis in future pregnancies,10,52,71 were unsure, or would not terminate an affected fetus.23,52,57 In actuality, 80–100% of the carrier couples identified utilized prenatal diagnosis,38,39,41,51,60,66,75,78,79,80,82,84,85 and the majority terminated an affected fetus.38,51,60,66,75,79,80,82,84 Only one study reported the continuation of an affected pregnancy, with the carrier couple having twins who were both identified as being affected.39

The dissemination of information from carriers to other family members about increased risk is often evaluated when exploring the outcomes of screening. The majority of carriers reported informing relatives of their carrier status,20,58,63,65,67,74,81 most frequently telling parents and siblings.74,81,86

Psychological factors associated with screening for CF carrier status

Concerns have been raised over the potential psychological harm of population screening for CF carrier status. Although there was an increase in anxiety on receiving a positive test result,42,50,67,74,79,83 this dissipated once partners were tested and found to be negative,65,79,83 following genetic counseling,71,78 or after a period of 3–6 months.42,50,71 Anxiety appears to be transient among carriers, with little to no anxiety present at 6–12 months or more after testing.65,74,78

There was no significant difference in anxiety between carriers and noncarriers37,39,73,78,84 and between those who were screened and those not screened.85 In the majority of studies, anxiety level was measured using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory, General Health Questionnaire, Miller Behavioral Style Scale, and/or the Tolerance for Ambiguity Scale.

On receiving test results, the majority of those screened were reassured, whereas some were slightly apprehensive.45 Most carriers expressed feelings of surprise, shock, and worry on receiving their positive test result,57,71,81 whereas some expressed negative feelings and troubling thoughts.87 All individuals who had carrier screening attributed negative feelings to being a carrier, whereas carriers attributed positive feelings to themselves but negative feelings to other carriers.64 A study involving secondary school students showed a marked increase in uncertainty regarding feelings of concern and self-esteem after receipt of test results.28 Some studies showed that carriers perceived their current health to be poorer than that of noncarriers,73,76 although other studies showed no difference between carriers and noncarriers for past, present, and future perception of health.67,84 Despite these reports, 83–97% of those screened, including carriers, felt that they made the right decision and would make the same decision again,20,34,69,78 with only 2–12% stating that they were unsure or regretted their decision to have screening.66,78

Discussion

The available studies of population-based screening for CF carrier status have positive implications for the routine offer of screening to pregnant couples, couples planning a pregnancy, and individuals wishing to know their carrier status. The review demonstrates the following for the majority of studies: positive attitudes toward the routine offer of CF carrier screening; high uptake of screening in a prenatal setting; correct recall and understanding of carrier status; high rate of testing of carrier’s partners; willingness to inform family members and relatives of increased risk if found to be a carrier; and no long-term psychological harm. Understanding of residual risk was poor in many of the studies evaluated in this review.

These studies are heterogeneous in a number of ways, including the setting in which screening was offered; populations who were offered screening; the cost of the test; how testing was offered; pretest counseling; pretest information; disclosure of test results; and posttest counseling. In addition, a number of the studies involved hypothetical screening; therefore, although the results are still important in determining predicted attitudes and behaviors toward screening, these might change on receipt of an actual offer of screening. Although there is some difficulty in comparing these studies, a great deal can still be learned.

The discovery of the CFTR gene in 1989, enabling CF carrier screening to take place, sparked a rise in research, with the majority of studies included in the review being published in the 1990s. The largest number of studies was conducted in the United States, in line with recommendations for the routine offer of CF carrier screening in that country. However, since the implementation of these recommendations, there has been limited evaluation. Fewer studies were based in the United Kingdom, which is currently reviewing its advice not to recommend routine screening. These UK studies often reported psychological factors in response to a policy recommendation to gather further data on the psychological consequences of carrier detection.88

Uptake rates are an important evaluation tool of screening programs. However, in a number of the studies included in this review, the uptake rate could not be reported because the overall number of individuals or couples who were offered screening was not recorded. Generally, uptake of CF carrier screening was higher in those who were pregnant at the time of offer as compared with those who were not pregnant or the general population. Screening was perceived as more relevant during pregnancy, with some nonpregnant individuals of reproductive age stating that they would not accept screening at this life stage.14,15,27

When determining attitudes and opinions toward the offer of screening, most studies showed that potential participants would like to receive an offer of screening, in addition to pretest information and counseling from their general practitioner or primary health-care provider, and would prefer a direct offer rather than a passive offer. An information leaflet or brochure on CF carrier screening was perceived to be useful in addition to the face-to-face information. Although this review does not report on the attitudes of health professionals toward CF carrier screening, studies have shown that they perceived various practical barriers to the offer of screening. Health professionals are often the gatekeepers of screening, and their attitudes, opinions, and knowledge regarding screening are significant in the effectiveness of offering population-based screening for CF carrier status. This is borne out by a number of studies that have shown that a doctor’s recommendation is an influencing factor in accepting screening.14,20,55,85

Potential participants believed that the best time to have CF carrier screening is before pregnancy because identification of carrier couples preconceptionally provides the most reproductive options, in addition to giving couples more time to make reproductive decisions, as compared with prenatal screening. Although this may be the most advantageous time to be screened, preconception screening was associated with lower uptake than prenatal screening due to lack of interest at this life stage; lack of preconception health-care settings in which to offer screening; and a large number of unplanned pregnancies.18 Offering CF carrier screening in high school has been proposed because it can reach a large proportion of the population.89 High uptake has been associated with screening in Jewish high schools, with 98% of Jewish high school students accepting an offer of carrier screening for a number of conditions, including CF.90 The delay in the use of information obtained from CF carrier screening in high school is the main criticism of this approach; the American College of Medical Genetics stated that carrier screening should “not be offered to adolescents as the information is only relevant for reproductive planning.”91 However, research has indicated that adolescents screened recalled their positive carrier status, had their partners tested, and used this information to make future reproductive decisions.92 Despite concerns that adolescents identified as carriers of CF would face stigmatization and discrimination from peers, research has shown that adolescent carriers have few negative psychological effects as a result of knowing their carrier status.92

The majority of studies reported that willingness to accept an offer of screening was associated with wanting to know carrier status, high perceived susceptibility, and avoiding having a child with CF. The main factors associated with declining an offer of screening were low perceived susceptibility, lack of intention to terminate a pregnancy, and lack of family history of CF. More than half of the studies in this review exploring these influencing factors did not involve an actual offer of screening. Therefore, the majority of factors mentioned are perceived to influence the decision for hypothetical screening but may or may not actually influence decisions when individuals are faced with an offer of screening. Increasing acceptance of CF carrier screening could be achieved by increasing knowledge, as perceived susceptibility and perceived severity appeared to be the main themes among the influencing factors. For example, absence of a family history of CF as a reason for declining screening highlights a lack of knowledge because the carrier rate is 1 in 25 and most children with CF are born to couples who do not have a family history of CF.93

Henneman et al32 found that those who declined screening had lower knowledge than those who accepted screening. Knowledge of CF and screening has been shown to be low before screening but to improve thereafter. A potential reason for this increase may be the perceived relevance of that information, particularly if the individual is found to be a carrier. Provision of posttest counseling is also likely to improve knowledge, with carriers usually receiving more follow-up than noncarriers.20

Lack of knowledge/understanding of residual risk has been one of the major issues to arise from this review. Although carrier screening for most diseases has a test sensitivity of nearly 100%, CF carrier screening has a test sensitivity of approximately 80% among Northern Europeans when screening for 23 CFTR mutations, each with a frequency equal to or greater than 0.1% in the CF population.2 Individuals who obtain a negative result for CF carrier screening, therefore, still have a residual risk of being a carrier and having an affected child. This has led to confusion among noncarriers and carriers with a noncarrier partner, with some of these individuals believing they have no risk of having a child with CF.

Approximately 70% of the target population in the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Netherlands stated that the results of screening for CF carrier status would influence their reproductive behavior.15,22,33 However, the review showed that the majority of carriers would not change their reproductive behavior as a result of their carrier status unless their partner was also found to be a carrier.

An outcome of population-based carrier screening is the reduction of CF in the population through the provision of reproductive choices to individuals and couples identified as carriers. This is borne out by the majority of carrier couples utilizing prenatal diagnosis and terminating an affected fetus. NBS also identifies parents as carrier couples and provides reproductive options for future pregnancies. In Australia, 67% of parents identified as carriers through NBS chose to use prenatal diagnosis when having more children. The implementation of carrier screening has been shown to be associated with a reduction in the incidence of CF, as judged by the number of infants with CF identified by NBS in both Massachusetts (United States) and northern Italy since 1999 and 1993, respectively94,95 However, there has been no reduction in the incidence of CF in Colorado, where screening for CF began in 1982.96

The dissemination of information by carriers to family members is important because they are at increased risk of being carriers of CF. This is particularly relevant if they are planning a pregnancy but is less so if they are not of reproductive age, do not have a partner, or have finished reproducing.20 Although most carriers stated that they informed family members of their carrier status, a study by McClaren et al97 evaluating cascade testing after a child is diagnosed with CF through NBS showed that identifying an individual as a carrier of CF usually results in an average of only 11% of family members being tested.

Psychological harm because of screening has been proposed as a barrier to the implementation of population-based CF carrier screening. Although there have been various studies reporting anxiety and feelings of poorer health in carriers, anxiety was generally transient, and perception of poor health reflected a lack of knowledge. The majority of studies reported little evidence of long-term psychological harm, with the provision of counseling. This is supported by Henneman et al,98 who reported that the potential psychological harms associated with population-based CF carrier screening are insufficient to warrant the refusal to offer carrier screening to the general population in the Netherlands.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that population-based CF carrier screening is generally associated with relatively high uptake, positive attitudes, correct recall and understanding of carrier status, and no long-term psychological harm. Although barriers to routinely implementing CF carrier screening in the population exist, they are not insurmountable. There would appear to be no psychosocial reasons why population-based CF carrier screening should not become part of regular health care.

Despite the considerable heterogeneity among the included studies, there is now a substantial body of evidence collected to inform programs. Needed now are large-scale studies of “routine” screening to evaluate—in a real-world setting—the perceived benefits, harms, barriers, motivators, and behaviors that have been identified in the literature so far.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

O’Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and charaterization of complementary DNA. Science 1989;245:1066–1073.

Moskowitz SM, Chmiel JF, Sternen DL, Cheng E, Cutting GR . CFTR-Related Disorders. In: GeneTests Medical Genetics Information Resource (database online). Copyright, University of Washington, Seattle. 1993–2013. http://www.genetests.org. Accessed 21 January 2013.

Dodge JA, Lewis PA, Stanton M, Wilsher J . Cystic fibrosis mortality and survival in the UK: 1947-2003. Eur Respir J 2007;29:522–526.

Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ . Mechanisms of disease: cystic fibrosis. New Engl J Med 2005;352:1992.

Castellani C, Massie J . Emerging issues in cystic fibrosis newborn screening. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16:584–590.

Sawyer SM, Cerritelli B, Carter LS et al. Reproductive behaviours in parents of children with cystic fibrosis changing their minds with time: a comparison of hypothetical and actual. Pediatrics 2006;118:649–656.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 486: Update on carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1028–1031.

Human Genetics Society of Australasia. Cystic fibrosis population screening position paper (Document No. PS02). HGSA: Sydney, Australia. http://www.hgsa.org.au/website/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/2010PS02-CYSTIC-FIBROSIS-POPULATION-SCREENING1.pdf. Accessed 4 December 2012.

UK National Screening Committee. Cystic fibrosis (pregnancy). UK NSC Policy Database. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/cysticfibrosis-pregnancy. Accessed 22 September 2012.

Decruyenaere M, Evers-Kiebooms G, Denayer L, Van den Berghe H . Cystic fibrosis: community knowledge and attitudes towards carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis. Clin Genet 1992;41:189–196.

Green JM . Principles and practicalities of carrier screening: attitudes of recent parents. J Med Genet 1992;29:313–319.

Magnay D, Wilson O, el Hait S, Balhamar M, Burn J . Carrier testing for cystic fibrosis: knowledge and attitudes within a local community. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1992;26:69–70.

Ten Kate LP, Tijmstra T . Community attitudes to cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Prenat Diagn 1990;10:275–276.

McClaren BJ, Delatycki MB, Collins V, Metcalfe SA, Aitken M . ‘It is not in my world’: an exploration of attitudes and influences associated with cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2008;16:435–444.

Poppelaars FA, Henneman L, Adèr HJ, et al. How should preconceptional cystic fibrosis carrier screening be provided? Opinions of potential providers and the target population. Community Genet 2003;6:157–165.

Ioannou L, Massie J, Lewis S, McClaren B, Collins V, Delatycki MB . 'No thanks'-reasons why pregnant women declined an offer of cystic fibrosis carrier screening. J Community Genet, in press.

Mennie M, Compton M, Gilfillan A, et al. Prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis: attitudes and responses of participants. Clin Genet 1993;44:102–106.

Poppelaars FA, van der Wal G, Braspenning JC, et al. Possibilities and barriers in the implementation of a preconceptional screening programme for cystic fibrosis carriers: a focus group study. Public Health 2003;117:396–403.

Ten Kate LP, Tijmstra T . Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Lancet 1989;2:973–974.

Ioannou L, Massie J, Collins V, McClaren B, Delatycki MB . Population-based genetic screening for cystic fibrosis: attitudes and outcomes. Public Health Genomics 2010;13:449–456.

Watson EK, Mayall E, Chapple J, et al. Screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis through primary health care services. BMJ 1991;303:504–507.

Watson EK, Williamson R, Chapple J . Attitudes to carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: a survey of health care professionals, relatives of sufferers and other members of the public. Br J Gen Pract 1991;41:237–240.

Botkin JR, Alemagno S . Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: a pilot study of the attitudes of pregnant women. Am J Public Health 1992;82:723–725.

Williamson R, Allison ME, Bentley TJ, et al. Community attitudes to cystic fibrosis carrier testing in England: a pilot study. Prenat Diagn 1989;9:727–734.

Twal M . Women’s perceptions of the value of genetic screening at different life stages. Health Sci: Dissertation Abstracts Int 1998;59:Abstract 2712-B.

Neiger R, Abuelo DN, Passero MA . Attitudes toward genetic testing for cystic fibrosis among college students. J Genet Couns 1992;1:219–226.

Welkenhuysen M, Evers-Kiebooms G, Decruyenaere M, Van den Berghe H, Bande-Knops J, Van Gerven V . Adolescents’ attitude towards carrier testing for cystic fibrosis and its relative stability over time. Eur J Hum Genet 1996;4:52–62.

Durfy SJ, Page A, Eng B, Chang PL, Waye JS . Attitudes of high school students toward carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. J Genet Couns 1994;3:141–155.

Cobb E, Holloway S, Elton R, Raeburn JA . What do young people think about screening for cystic fibrosis? J Med Genet 1991;28:322–324.

Poppelaars FA, Henneman L, Adèr HJ, et al. Preconceptional cystic fibrosis carrier screening: attitudes and intentions of the target population. Genet Test 2004;8:80–89.

Clayton EW, Hannig VL, Pfotenhauer JP, Parker RA, Campbell PW 3rd, Phillips JA 3rd . Lack of interest by nonpregnant couples in population-based cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Am J Hum Genet 1996;58:617–627.

Henneman L, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg HM, et al. Participation in preconceptional carrier couple screening: characteristics, attitudes, and knowledge of both partners. J Med Genet 2001;38:695–703.

Henneman L, Bramsen I, van Kempen L, et al. Offering preconceptional cystic fibrosis carrier couple screening in the absence of established preconceptional care services. Community Genet 2003;6:5–13.

Henneman L, Weijers-Poppelaars FAM, Ten Kate LP . Desirability and feasibility of preconception cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Neth J Med 2004;148:618–622.

Sturm EL, Ormond KE . Adjunct prenatal testing: patient decisions regarding ethnic carrier screening and fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Genet Couns 2004;13:45–63.

Cuckle H, Quirke P, Sehmi I, et al. Antenatal screening for cystic fibrosis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:795–799.

Harris HJ, Scotcher D, Craufurd D, Wallace A, Harris R . Cystic fibrosis carrier screening at first diagnosis of pregnancy in general practice. Lancet 1992;339:1539.

Jung U, Urner U, Grade K, Coutelle C . Acceptability of carrier screening for cystic fibrosis during pregnancy in a German population. Hum Genet 1994;94:19–24.

Witt DR, Schaefer C, Hallam P, et al. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote screening in 5,161 pregnant women. Am J Hum Genet 1996;58:823–835.

Fang CY, Dunkel-Schetter C, Tatsugawa ZH, et al. Attitudes toward genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis among pregnant women: the role of health beliefs and avoidant coping style. Womens Health 1997;3:31–51.

Harris H, Scotcher D, Hartley N, Wallace A, Craufurd D, Harris R . Cystic fibrosis carrier testing in early pregnancy by general practitioners. BMJ 1993;306:1580–1583.

Bekker H, Modell M, Denniss G, et al. Uptake of cystic fibrosis testing in primary care: supply push or demand pull? BMJ 1993;306:1584–1586.

Tambor ES, Bernhardt BA, Chase GA, et al. Offering cystic fibrosis carrier screening to an HMO population: factors associated with utilization. Am J Hum Genet 1994;55:626–637.

Livingstone J, Axton RA, Mennie M, Gilfillan A, Brock DJ . A preliminary trial of couple screening for cystic fibrosis: designing an appropriate information leaflet. Clin Genet 1993;43:57–62.

Mennie ME, Liston WA, Brock DJ . Prenatal cystic fibrosis carrier testing: designing an information leaflet to meet the specific needs of the target population. J Med Genet 1992;29:308–312.

Myers MF, Bernhardt BA, Tambor ES, Holtzman NA . Involving consumers in the development of an educational program for cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Am J Hum Genet 1994;54:719–726.

Clayton EW, Hannig VL, Pfotenhauer JP, Parker RA, Campbell PW 3rd, Phillips JA 3rd . Teaching about cystic fibrosis carrier screening by using written and video information. Am J Hum Genet 1995;57:171–181.

Castellani C, Perobelli S, Bianchi V, et al. An interactive computer program can effectively educate potential users of cystic fibrosis carrier tests. Am J Med Genet A 2011;155A:778–785.

Flinter FA, Silver A, Mathew CG, Bobrow M . Population screening for cystic fibrosis. Lancet 1992;339:1539–1540.

Bekker H, Denniss G, Modell M, Bobrow M, Marteau T . The impact of population based screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis. J Med Genet 1994;31:364–368.

Brock DJ . Prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis: 5 years’ experience reviewed. Lancet 1996;347:148–150.

Miedzybrodzka ZH, Hall MH, Mollison J, et al. Antenatal screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis: randomised trial of stepwise v couple screening. BMJ 1995;310:353–357.

Honnor M, Zubrick SR, Walpole I, Bower C, Goldblatt J . Population screening for cystic fibrosis in Western Australia: community response. Am J Med Genet 2000;93:198–204.

Fries MH, Bashford M, Nunes M . Implementing prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis in routine obstetric practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:527–534.

Hall J, Fiebig DG, King MT, Hossain I, Louviere JJ . What influences participation in genetic carrier testing? Results from a discrete choice experiment. J Health Econ 2006;25:520–537.

Sparbel KJ, Williams JK . Pregnancy as foreground in cystic fibrosis carrier testing decisions in primary care. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2009;13:133–142.

Harris H, Scotcher D, Hartley N, Wallace A, Craufurd D, Harris R . Pilot study of the acceptability of cystic fibrosis carrier testing during routine antenatal consultations in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:225–227.

Delvaux I, van Tongerloo A, Messiaen L, et al. Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis in a prenatal setting. Genet Test 2001;5:117–125.

Mennie ME, Gilfillan A, Compton ME, Liston WA, Brock DJ . Prenatal cystic fibrosis carrier screening: factors in a woman’s decision to decline testing. Prenat Diagn 1993;13:807–814.

Grody WW, Dunkel-Schetter C, Tatsugawa ZH, et al. PCR-based screening for cystic fibrosis carrier mutations in an ethnically diverse pregnant population. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:935–947.

Hill R, Stanisstreet M, Boyes E, O’Sullivan H . Public lacks knowledge about genetic testing and gene therapy. BMJ 1995;311:1370.

Bernhardt BA, Chase GA, Faden RR, et al. Educating patients about cystic fibrosis carrier screening in a primary care setting. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:336–340.

Kaplan F, Clow C, Scriver CR . Cystic fibrosis carrier screening by DNA analysis: a pilot study of attitudes among participants. Am J Hum Genet 1991;49:240–242.

Gordon C, Walpole I, Zubrick SR, Bower C . Population screening for cystic fibrosis: knowledge and emotional consequences 18 months later. Am J Med Genet A 2003;120A:199–208.

Brandt NJ, Schwartz M, Skovby F, Clausen H . [A follow-up study of carriers of cystic fibrosis]. Ugeskr Laeg 1996;158:4623–4627.

Clausen H, Brandt NJ, Schwartz M, Skovby F . Psychological and social impact of carrier screening for cystic fibrosis among pregnant woman–a pilot study. Clin Genet 1996;49:200–205.

Clausen H, Brandt NJ, Schwartz M, Skovby F . Psychological impact of carrier screening for cystic fibrosis among pregnant women. Eur J Hum Genet 1996;4:120–123.

Marteau TM, Michie S, Miedzybrodzka ZH, Allanson A . Incorrect recall of residual risk three years after carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: a comparison of two-step and couple screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:165–169.

Hartley NE, Scotcher D, Harris H, et al. The uptake and acceptability to patients of cystic fibrosis carrier testing offered in pregnancy by the GP. J Med Genet 1997;34:459–464.

Payne Y, Williams M, Cheadle J, et al. Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis in primary care: evaluation of a project in South Wales. The South Wales Cystic Fibrosis Carrier Screening Research Team. Clin Genet 1997;51:153–163.

Wake SA, Rogers CJ, Colley PW, Hieatt EA, Jenner CF, Turner GM . Cystic fibrosis carrier screening in two New South Wales country towns. Med J Aust 1996;164:471–474.

Mitchell J, Scriver CR, Clow CL, Kaplan F . What young people think and do when the option for cystic fibrosis carrier testing is available. J Med Genet 1993;30:538–542.

Axworthy D, Brock DJ, Bobrow M, Marteau TM . Psychological impact of population-based carrier testing for cystic fibrosis: 3-year follow-up. UK Cystic Fibrosis Follow-Up Study Group. Lancet 1996;347:1443–1446.

Watson EK, Mayall ES, Lamb J, Chapple J, Williamson R . Psychological and social consequences of community carrier screening programme for cystic fibrosis. Lancet 1992;340:217–220.

Doherty RA, Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Erickson JL, Haddow JE . Couple-based prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis in primary care settings. Prenat Diagn 1996;16:397–404.

Henneman L, Bramsen I, van der Ploeg HM, ten Kate LP . Preconception cystic fibrosis carrier couple screening: impact, understanding, and satisfaction. Genet Test 2002;6:195–202.

Dacus J, Mabie B, Gailey T, Rogers C, Likes C, Metcalf L . Cystic fibrosis screening at the Greenville Hospital System. J S C Med Assoc 2006;102:14–16.

Levenkron JC, Loader S, Rowley PT . Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: test acceptance and one year follow-up. Am J Med Genet 1997;73:378–386.

Mennie ME, Gilfillan A, Compton M, et al. Prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis. Lancet 1992;340:214–216.

Schwartz M, Brandt NJ, Skovby F . Screening for carriers of cystic fibrosis among pregnant women: a pilot study. Eur J Hum Genet 1993;1:239–244.

Boulton M, Cummings C, Mayall E, Watson E, Williamson R . A video to inform and reassure autonomous cystic fibrosis carriers identified by a community screening programme. Health Educ J 1996;55:203–214.

Massie J, Petrou V, Forbes R, et al. Population-based carrier screening for cystic fibrosis in Victoria: the first three years experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:484–489.

Mennie ME, Compton ME, Gilfillan A, et al. Prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis: psychological effects on carriers and their partners. J Med Genet 1993;30:543–548.

Livingstone J, Axton RA, Gilfillan A, et al. Antenatal screening for cystic fibrosis: a trial of the couple model. BMJ 1994;308:1459–1462.

Loader S, Caldwell P, Kozyra A, et al. Cystic fibrosis carrier population screening in the primary care setting. Am J Hum Genet 1996;59:234–247.

Ormond K . Implementing prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis in routine obstetric practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:904; author reply 904–904; author reply 905.

Marteau TM, Dundas R, Axworthy D . Long-term cognitive and emotional impact of genetic testing for carriers of cystic fibrosis: the effects of test result and gender. Health Psychol 1997;16:51–62.

Murray J, Cuckle H, Taylor G, Littlewood J, Hewison J . Screening for cystic fibrosis. Health Technol Assess 1999;3:i–iv, 1.

Gason AA, Delatycki MB, Metcalfe SA, Aitken M . It’s “back to school” for genetic screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2006;14:384–389.

Ioannou L, Massie J, Lewis S, et al. Evaluation of a multi-disease carrier screening programme in Ashkenazi Jewish high schools. Clin Genet 2010;78:21–31.

Multhaupt-Buell TJ, Lovell A, Mills L, Stanford KE, Hopkin RJ . Genetic service providers’ practices and attitudes regarding adolescent genetic testing for carrier status. Genet Med 2007;9:101–107.

Mitchell JJ, Capua A, Clow C, Scriver CR . Twenty-year outcome analysis of genetic screening programs for Tay-Sachs and beta-thalassemia disease carriers in high schools. Am J Hum Genet 1996;59:793–798.

McClaren BJ, Metcalfe SA, Amor DJ, Aitken M, Massie J . A case for cystic fibrosis carrier testing in the general population. Med J Aust 2011;194:208–209.

Hale JE, Parad RB, Comeau AM . Newborn screening showing decreasing incidence of cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:973–974.

Castellani C, Picci L, Tamanini A, Girardi P, Rizzotti P, Assael BM . Association between carrier screening and incidence of cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2009;302:2573–2579.

Sontag MK, Wagener JS, Accurso FJ, Sagel SD . Consistent incidence of cystic fibrosis in a long-term newborn screen population [abstract]. Pediat Pulmonol 2008; 43:272 (Abstract A203).

McClaren BJ, Metcalfe SA, Aitken M, Massie RJ, Ukoumunne OC, Amor DJ . Uptake of carrier testing in families after cystic fibrosis diagnosis through newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:1084–1089.

Henneman L, Poppelaars FA, ten Kate LP . Evaluation of cystic fibrosis carrier screening programs according to genetic screening criteria. Genet Med 2002;4:241–249.

Wald NJ, George L, Wald N, MacKenzie IZ . Further observations in connection with couple screening for cystic fibrosis. Prenat Diagn 1995;15:589–590.

Slostad J, Stein QP, Flanagan JD, Hansen KA . Screening for mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene in an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril 2007;88:1687–1688.

Mélançon MJ, De Braekeleer M . Adolescents’ attitude towards carrier testing for cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Genet 1996;4:305–306.

Coiana A, Faa’ V, Carta D, Puddu R, Cao A, Rosatelli MC . Preconceptional identification of cystic fibrosis carriers in the Sardinian population: A pilot screening program. J Cyst Fibros 2011;10:207–211.

Donaldson C, Shackley P, Abdalla M, Miedzybrodzka Z . Willingness to pay for antenatal carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. Health Econ 1995;4:439–452.

Sparbel KJH . Cystic fibrosis carrier testing decision-making for women in primary care: role of context. Nurs Health Sci 2007;9:234.

O’Connor BV, Cappelli M . Health beliefs and the intent to use predictive genetic testing for cystic fibrosis carrier status. Psychol Health Med 1999;4:157–169.

Acknowledgements

M.B.D. is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) practitioner fellow. S.L. was funded by an NHMRC Capacity Building Grant in Population Health. M.B.D. is a consultant with Healthscope Pathology. This study was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Material

(XLS 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ioannou, L., McClaren, B., Massie, J. et al. Population-based carrier screening for cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of 23 years of research. Genet Med 16, 207–216 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.125

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.125

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Couples’ experiences with expanded carrier screening: evaluation of a university hospital screening offer

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

The prevalence, genetic complexity and population-specific founder effects of human autosomal recessive disorders

npj Genomic Medicine (2021)

-

Attitudes of relatives of mucopolysaccharidosis type III patients toward preconception expanded carrier screening

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

Sequencing as a first-line methodology for cystic fibrosis carrier screening

Genetics in Medicine (2019)

-

Direct-to-consumer carrier screening for cystic fibrosis via a hospital website: a 6-year evaluation

Journal of Community Genetics (2019)