Abstract

Purpose:

Return of individual research results from genomic studies is a hotly debated ethical issue in genomic research. However, the perspective of key stakeholders—institutional review board (IRB) professionals—has been missing from this dialogue. This study explores the positions and experiences of IRB members and staff regarding this issue.

Methods:

In-depth interviews with 31 IRB professionals at six sites across the United States.

Results:

IRB professionals agreed that research results should be returned to research participants when results are medically actionable but only if the participants want to know the results. Many respondents expected researchers to address the issue of return of results (ROR) in the IRB application and informed-consent document. Many respondents were not comfortable with their expertise in genomics research and only a few described actual experiences in addressing ROR. Although participants agreed that guidelines would be helpful, most were reticent to develop them in isolation. Even where IRB guidance exists (e.g., Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) lab certification required for return), in practice, the guidance has been overruled to allow ROR (e.g., no CLIA lab performs the assay).

Conclusion:

An IRB–researcher partnership is needed to help inform responsible and feasible institutional approaches to returning research results.

Genet Med 2012:14(2):215–222

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most common ethical dilemmas in human genomic research is the challenge of deciding whether to tell participants what researchers discover about their genomes.1,2,3,4,5 With the accelerating use of genomic analysis techniques, researchers are increasingly encountering research results that are associated with potential as well as known health implications. Although this challenge was anticipated in the literature since early in the Human Genome Project,6 and a robust effort has been devoted to developing recommendations and models to address this issue,1,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 there is currently no national policy to guide researchers, research participants, or institutional review board (IRB) professionals. In practice, decisions related to return of results (ROR) are left to local institutions.

The 2007 National Institutes of Health (NIH) data-sharing policy on genome-wide association studies suggests that “contributing institutions and IRBs may wish to establish policies to determine when it is appropriate to return individual findings from research studies.”21 IRBs are a logical place for researchers to look for guidance on deciding whether and how to return research results because they are charged with protecting the rights and interests of research participants in the review and approval of human genomic research protocols. Studies show that researchers identify IRBs as the relevant authority in this regard22 and that IRB chairs and human subjects professionals recognize that returning results is an important human subjects research issue,18,23 yet few studies have analyzed how IRB professionals are thinking about this issue and what they are doing to address it.

If, in the absence of federal public policy guidance, IRBs are to develop a shared capacity to help investigators address the challenge of returning results, it will be important to understand their baseline experiences and local practices. The purpose of the current study was to begin that assessment by analyzing IRB perspectives and approaches for returning research results of genomic studies to individual research participants. The study is part of a larger effort to evaluate experiences and views of IRBs and genomic researchers in the review and conduct of genetic and genomic research.23,24

Materials and Methods

Population

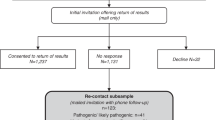

We invited IRB members and staff at four major academic centers and two research hospitals across the United States to participate in semistructured interviews. We first contacted the IRB director at each site to identify the most appropriate method for recruiting IRB professionals. To protect the respondents, several sites requested that neither the site name nor the respondent’s position on the IRB (e.g., chair, cochair) be reported in this paper. Individuals who had been active members of an IRB within the past two years and whose job responsibilities included the review of biomedical research protocols were eligible to participate.

Approach and analysis

Focus groups conducted at two of the six sites informed the development of an interview guide that was used in subsequent one-on-one semistructured interviews. These one-time interviews were conducted mainly in person (and occasionally by phone) and lasted 45–60 min. Owing to the time limit, not every interview included all questions in the guide, but all respondents answered the following questions: “Do you think results of genetic or genomic research studies should be provided to individual participants? Why or why not? Under what conditions should research results be returned?” These questions also gave respondents an opportunity to describe their experiences addressing this issue in their IRB. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed and assigned a study identification code. No personal identifiers were collected and no master list was maintained that could link the code to the respondent. Verbal consent was obtained from all but one site, which required written consent.

We followed criteria established for qualitative methods to assure the rigor and trustworthiness of data collection, coding, and analysis procedures.25,26,27 Briefly, transcripts were first checked for accuracy and the interview text was then analyzed for content related to return of research results. After development of a coding schema by the study team, coding was performed independently by two analysts and compared for agreement. Areas of disagreement were resolved through discussion and, on occasion, by a third coder. The ATLAS.ti software program was used to aid in indexing, searching, and retrieving sections of data related to ROR. In-depth analysis of the coded data was conducted by team review through an iterative process of analytic induction to document and interpret themes and patterns using a grounded theory approach.28,29,30 Responses by IRB members and staff were initially reviewed separately and then compared. Because we did not observe differences in perspectives between the two groups, all responses in this paper are reported as one group of IRB professionals.

We also collected demographic information, including sex, age, education, profession, years of experience with the IRB, average number of genetic or genomic research studies reviewed per month, and experience conducting or participating in genetic or genomic research.

This study was reviewed and approved by the IRBs at each of the six sites.

Results

Demographics of respondents

Thirty-one individuals comprising 24 IRB members and 7 staff participated in the interviews; 18 of the individuals were female. All but one respondent reported experience reviewing genetic or genomic studies on a monthly basis: 20 reported reviewing an average of one to three, whereas 10 reviewed more than four per month. Eleven reported a current or past role in genetic or genomic research as coinvestigator (n = 5), consultant (n = 3), or research staff (n = 3). IRB members represented a spectrum of professions, including 12 health-care providers, 8 researchers, and 1 each representing law, ethics, and a non-scientist community member (one respondent did not report profession).

General perspectives on and experiences with return of individual results

These IRB professionals understood returning individual results as a perplexing issue, describing it as “an incredibly sticky wicket” and “a big kettle of worms.” They described a range of issues that make this topic complicated to address, including the new, fast-paced, and “rapidly evolving nature” of genomic research and its “broad scope,” “with many contexts.” Respondents also described their uncertainty about the reliability of the research result, especially if the result was preliminary, and the psychological consequences of returning results to individual research participants. The frequent and complex interrelationships among these issues adds to the difficulty in responding to questions about whether individual results should be returned (see Table 1 [participant 3 (P3)])

For many respondents, the interview itself offered the first opportunity to analyze the issues associated with ROR and prompted interest in addressing this topic in their IRB: “Not sure if the IRB has ever really thought about that [return of individual results] . . . but I think I’ll have a discussion tomorrow.” Several respondents who did not have experience with returning results anticipated that this issue was going to be more prevalent in the near future as genetics become more routinely integrated into study designs. One respondent remarked, “Well, a great many drug protocols now, or even device protocols, are including genetic sub-studies.” Respondents without special expertise in genetics discussed their difficulty in evaluating the implications for research participants, especially in the absence of national guidance (see Table 1 [P4]).

Ten respondents had either thought about this issue before (n = 5) or had participated in deciding whether to return a genetic or genomic research result (n = 5). In these examples, the IRBs’ moral responsibility in addressing this issue was often highlighted (see Table 1 [P21]). In two examples, respondents described situations they faced regarding the decision of returning research results that were not obtained in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA)-approved laboratory. In both situations, the research assay was available only in the researcher’s laboratory, and no CLIA-approved laboratory had the capacity to perform the assay. Although their local IRB guidance indicated that only results obtained in CLIA-approved laboratories could be returned, in both situations, this guidance was overruled and the individual result was communicated to the research participant. In one of these examples, the respondent reported that a researcher had identified several genes associated with hypercoagulability in an individual research participant. The IRB considered the return of this result to have a low risk of potential harm and high expected benefit to the individual and recommended returning it:

Well, you know, if you had this knowledge, at a minimum you’d get up several times in a five-hour flight across the country. And that may be about the extent of what you can do, but it might keep somebody from having a stroke. And so, in that case, the IRB, I think, felt pretty strongly that this was probably information that should be shared. [P21]

Regardless of the level of experience or expertise, all respondents were able to describe multiple concerns they associated with ROR, identifying many of the common issues described in the ROR literature.1,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 Many concerns centered around the risks of returning a research result and how the research participant would respond to and/or act on that result. Specific concerns included the emotional and psychosocial consequences (e.g., anxiety, worry, family discord), lifestyle changes and decisions (e.g., reproductive choices, employment), and the potential for economic harm (e.g., as a result of losing insurance).

Positions on return of individual results

A spectrum of positions was articulated including the need to respect the research subject’s right to know/not know research results while weighing the potential negative consequences of returning individual results with anticipated benefit. Similar to the literature,1,31 there was general agreement (29/31) that preliminary, unvalidated results should not be returned, although many respondents did not specify what they meant by preliminary or unvalidated. Respondents discussed the importance of validating results, both analytically and clinically ( Table 1 [P15], [P23]).

Unique positions were also articulated. A respondent indicated that, based on ethical and moral principles, research results should almost always be returned ( Table 1 [P16]). Another respondent indicated that because “it is still research,” the mutation status should be returned, but not the interpretation of what that mutation means (e.g., the mutation may be associated with developing a certain disease or responding to a certain drug).

Respondents also discussed the concept of future consideration of research results and the importance of the reliability and utility of the research result, both now and in the future. Nearly one-third (n = 10) of our respondents highlighted the need to consider how a currently uncertain research result might have implications for the future health of the research participant, especially if the researcher maintained contact with research participants over time and maintained a registry of research results:

But something we try to keep in mind, and discuss sometimes with the researchers, is that it’s true that you’re just at the research stage and what you’re looking at right now isn’t necessarily meaningful, but . . . 10 years down the road you may find that information is meaningful. [P27]

Respondents also described concerns about returning individual results both related and unrelated (unexpected or incidental) to the study aims. Overall, most respondents were supportive of returning validated individual results if the research subject desired; however, the provision of such results to individual research subjects was conditioned on a variety of factors.

Conditions for return of individual results

Foremost in the dialogue on conditions for ROR was the need to respect and consider the research subject’s desire to know or not know the research result. Some respondents also described the need to address the implications of returning the result, especially for the individual and/or his or her family (e.g., how to make sense of the result, especially if there was no medical intervention) and, to a lesser degree, for the researcher or research community (e.g., the infrastructure, resources, and logistics that would be required to return research results to individual research subjects). Conditions for return are part of a dynamic circle of often interrelated and overlapping perspectives and criteria.

The most frequent conditions or criteria for returning an individual genetic research result favored a clinical utility perspective (25/31), where results should have “clinical significance,” “be serious or life threatening,” and/or be medically actionable (e.g., a medical intervention was available). Respondents also supported return if withholding a research result would cause clinical or health harm, now or in the future. A personal utility perspective, based on respect for the research subject, was also expressed. Different justifications for this perspective included the position that returning information learned about a research subject was a form of reciprocity for participating in the research, that results could have personal meaning or represent empowerment for the research subject and could provide the opportunity to benefit from non-medical interventions (e.g., lifestyle changes, reproductive decision making, investing in long-term care or additional health or life insurance, changing career path). Some conditions, such as the need to validate a result in a “CLIA-approved laboratory” prior to return, reflected concerns from both the clinical and the personal utility perspectives.

Process to manage ROR

Role of IRB in deciding whether to return a particular research result. Most respondents indicated that a team of people should be involved in ROR decisions, including the research investigator, scientific and other medical peers, other experts in the field, a genetic counselor, a medical geneticist, and the individual’s treating physician. There was limited mention of the research subject or research advocate being involved in the decision-making process, except to decide whether he or she wanted to know the result.

However, respondents did not agree on the specific role that the IRB should play in decision making. Although many indicated that the IRB should be actively involved in making the decision, others were not comfortable with this role and suggested that the IRB should “oversee the process” of decision making, “I’m not sure that we have the expertise as a body to do that [make the decision]. We can raise questions and we can bring up issues that we think need to be addressed” [P3]. In this oversight role, the IRB would not be involved in actual decision making per se, but would ensure that an appropriate, ethical process was followed for decision making, including how the research result was communicated to the research participant. Experience with conducting or reviewing genetic research or years on the IRB did not seem to influence the respondent’s position on the role the IRB should play in this process.

Approaches to managing ROR. Several respondents described guidelines or approaches that were in place at their institution for returning results. However, none indicated that a formal process was established to determine whether to return an individual result, who should be involved in making that determination, and how the result should be communicated to the research subject, if return was warranted. Table 2 summarizes the approaches reported by our respondents to managing ROR. Some respondents indicated that the ROR issue is addressed at the beginning of the study, at the time of IRB review, especially for results related to the study aims. Researchers were expected to indicate in the IRB application and consent document whether research results will be returned and, if so, to offer the research subjects’ options for whether they wanted to know this information. This approach is similar to recommendations from the 1999 National Bioethics Advisory Commission.32 One respondent indicated that the researcher should provide in the IRB application “an honest and thought-through risk and benefit analysis [of whether or not meaningful results might be obtained and/or should be returned]” [P4]. When ROR issues arose after initial IRB review, during the study or after study termination, many respondents considered their deliberations to be “more problematic,” mainly because there were no rules to follow. Many situations described at these times were consistent with finding an incidental result, “stumbling over a medical condition,” rather than one related to the research aims. “Especially if it’s [an incidental result] an issue that could significantly affect the life of the subject, I think it should be disclosed” [P30]. Respondents indicated that situations arising after initial IRB review would be handled, “similar to other IRB issues” on a case-by-case basis, bringing in the appropriate experts. Many respondents voiced that an important factor in the decision-making process is “whether there’s something you can do about it. . . . if there’s not a step that the study participant could take to ward off bad consequences or you know to improve his or her health, then I don’t think so” [P12].

As indicated earlier, some respondents described institution policies regarding CLIA-approved laboratory validation: “Our institution has taken a hard line, ‘No, you can’t [return results] if it’s not a CLIA-approved lab’” [P27]. Respondents also described policies that required that results be communicated by a professional trained in discussing genetic or genomic results with individuals. However, as described earlier, sometimes these policies (e.g., no CLIA-approved laboratory could perform an assay) were overruled to allow ROR.

Desire for guidance

Although respondents were in favor of having some form of guidance regarding whether to return a research result, they differed in the type of information they felt was needed. Some wanted specific rules or regulations to follow, especially “because it still feels to me that it’s a new area” [P11]. Others preferred “general ground rules” to follow to preserve the subjective and interpretive nature of IRB review: “I get really nervous about setting definitive [rules]. So I know everyone likes to operationalize everything, but I think that you could potentially miss a lot” [P1]. The participant added that because of the different contexts of ROR situations, “everything’s different, everything’s unique and everything can go one of 10 different ways” [P1].

Some respondents suggested plans for managing ROR situations (summarized in Table 3 ). This included an “optimal” approach to validating a research result and a two-tiered process for decision making. For assay validation, it was suggested that the assay be repeated with a new sample (or second aliquot of the current sample), and ideally with a second validated test, preferably performed in a clinical laboratory but definitely in a CLIA-approved laboratory. The two-tiered process for decision making included a first tier that would focus on “judging the significance, validity, and actionability of the finding” and involve the researcher, his or her peer group, relevant clinicians and other experts in the field, and the IRB. The second tier would consider the “psychosocial implications” of returning the finding to the research subject and would include the IRB, genetic counselors, the treating physician (if the research subject was also a patient), psychologists, and ethicists. If both tiers favored return, the final step would include developing an appropriate process to communicate the research finding, including asking research participants whether they wanted to know a research finding, how the finding should be presented (e.g., in person or by phone) and by whom (e.g., caring, skilled professional), how to determine the appropriate content and scope of information to be communicated (e.g., probability, positive predictive value), and the type of follow-up counseling (e.g., genetic and/or psychological) and care needed, if any. This approach is similar to that described by Kohane et al.20 Some respondents also recognized the requirement for an infrastructure and resources to support this process.

Discussion

Although our data reflect the perspectives of our respondents and may not be generalizable to all IRB professionals, they offer important insights regarding the challenges that IRBs may face as they address ROR. First is the knowledge and expertise required to appropriately analyze these issues, especially in the context of a rapidly changing field where unprecedented amounts of genomic and phenotypic data are gained and shared at an extraordinary pace and the associations between these findings and disease development may change just as quickly. Second, although return of individual research results is not a new concept in clinical research—imaging studies have had a long history of revealing incidental findings that are communicated to research subjects33,34—ROR that have clinical relevance from basic science studies, especially in genomic research, is a new concern. For some of our respondents, the interview process itself provided one of the first opportunities for in-depth analysis of this issue. Third, the increase in genomic studies that IRBs anticipate reviewing in the future creates even more tension regarding how to address the issue of returning research results. Finally, and perhaps most important, is the lack of national guidance on this issue upon which IRB professionals can anchor their decisions. Neither the Common Rule nor current Office for Human Research Protections guidance address the issue of return of individual research results.1,31 Many respondents in our study were not comfortable developing local policies in isolation. Even those IRBs that have some guidelines in place, including the requirement to validate research results in a CLIA-approved lab before return, found that some real-life situations precluded them from complying with their own rule.

However, despite these challenges and expressions of perplexity, respondents in our study were very thoughtful in trying to integrate all legitimate perspectives on this issue and articulated many of the concerns previously described in the literature.1,5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 These concerns reflected several dimensions of and individual thresholds for uncertainty, including the broad scope of the science juxtaposed with the highly contextual nature of each ROR scenario, and the challenges of appropriately assessing the analytical and clinical validity and clinical utility of a particular research result. The concern of having an individual act on research results that may be incorrect or have low predictive power, or of providing a research result that predicts a condition that has no medical intervention, fueled many of the uncertainties regarding how to appropriately assess potential risk and anticipated benefit. However, our respondents were firm in their position that research participants’ right to know/not know information about themselves be respected and they supported the return of validated, medically actionable results. These positions are similar to those reported by genetic researchers.22,35 Two studies with genetic/genomic researchers, using survey and qualitative methods, respectively, both identified clinical utility, respect for participants, and minimizing harm to participants as the common reasons for determining whether to return results.22,35 Participants in the qualitative study also considered the IRB to be a main authority to ensure that rules were being adhered to before researchers took action.22 However, as our study demonstrates, this can be a challenge when IRBs are still in the process of developing their own guidelines.

Only a few other studies have reported perspectives of IRBs on ROR.23,36 Lemke et al. conducted a survey study with members of a professional group overseeing human subjects research where 78% agreed that an “ethical duty existed to return individual research results that could affect a participant’s health or health care.”23 This view was also supported by the respondents in our study, taking into account contextual variables, such as the type of disease in question and the strength of the association of the result with disease development or response to therapy. The contextual nature of the ROR scenario was further highlighted by Wolf et al. in a study in which IRB chairs were presented with a scenario in which banked DNA was used in a research study to evaluate risk of Alzheimer disease.36 Nearly all IRB chairs in Wolf’s study expressed a desire to have predefined criteria regarding returning results.36 Although respondents in our study also wanted guidance on ROR, the type of guidance differed among the individuals: some wanted more concrete guidelines; others preferred ground rules or best practices to guide them.

We found that respondents often used similar terms in different ways or the same term to encompass a general concept without defining or clarifying what that term meant. The lack of a common nomenclature is a long-standing problem in human subjects research, especially in human specimen research and biobanking.37 In our study, the frequent use of the terms “validated” or “clinical significance” without identifying the threshold for meeting those descriptions can hinder communication and decision making among IRBs, researchers, and research participants. Even in the research community, agreement is lacking regarding what these terms mean and how to measure them consistently.1

We also learned new perspectives. First, many of our respondents expressed a need to consider the meaning of a research result not only today but also in the future. This concern was described especially when the researcher is maintaining contact with the research subject over time and is maintaining a registry or database of research results. The implication was that researchers may have a long-term responsibility to their research subjects to monitor the literature for the clinical relevance, validity, and utility of stored research results and communicate relevant information to the research subjects in the future. In contrast to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommendations suggesting that researchers are responsible for ROR only for the length of time of the study,18 our respondents did not put a time limit on the responsibility for monitoring currently uncertain results for future relevance. Second, we learned that IRB professionals have a range of views regarding whether the IRBs should play an active role in decision making about returning individual results. Some respondents felt that the IRB should oversee the decision-making process but not necessarily be a decision maker. Finally, although there was agreement that results should be returned to individuals who want them, there was little mention about how to incorporate research participants’ views or definitions on what conditions would constitute personal or clinical utility.

The most challenging tension for IRBs in regulating the return of individual research results, however, may be how the practice blurs the line between research and clinical care.34,38 IRBs are responsible for the ethical conduct of research, not the ethical conduct of clinical care. Research is meant to benefit society, not the individual research subject. Yet, in our study, and in society today, “a special power was associated with genomic information.”39 Our respondents expected that genomic or genetic studies would provide important clinical information for the research participant. And therein lies the conflict. The expectation for individual benefit is antithetical to the traditional concept of research. Addressing the return of individual research results that may be acted upon by the research participant crosses the boundary between research and clinical care. However, in our study and others, the communication of information that may benefit the research subject may also be considered part of the IRB’s moral obligation in their role to protect research subjects.23 It is not surprising that respondents expressed different views regarding the responsibility of the IRB to be actively involved in deciding whether a research result should be returned to an individual research subject. It is also not surprising that we lack national guidance.

Next steps: an IRB–researcher partnership

As IRBs are faced with real-life ROR situations, they will be forced to make decisions and develop management plans. Ground rules (and the range of acceptable interpretations) will need to be developed to address what conditions are either necessary or sufficient criteria for ROR(e.g., should actionable but unvalidated results be returned and what constitutes validity) and what situation trumps another. Although much effort is being devoted to the development of national and international policies for disclosing the results of genomic studies to research participants, there are opportunities at the local level to facilitate this process. One is the development of a partnership between IRB professionals and genomic researchers to approach the issue of ROR at their institution. Both IRB professionals and genomic researchers could benefit from a collaborative approach to addressing this issue, with each providing the necessary context and details to inform local management plans. Most important, research participants and the local community could also benefit from this partnership. The partnership could help assess local needs and develop management plans to meet those needs ( Table 4 ). Training exercises involving contextually-based case scenarios could be developed to provide IRBs and researchers with practice in collectively conducting risk/benefit analyses and opportunities to understand each other’s concerns in addressing this issue. Similarly, such exercises could provide opportunities to develop a common nomenclature of relevant terms and examine the logistics, infrastructure, and resources needed to support ROR. The partnership could lead to the development of a management plan that incorporates ways to address mutual concerns. In addition, the naturally occurring experiments that IRBs conduct in their research oversight responsibilities could be studied and analyzed, evaluating factors influencing development of different ROR policies and procedures. Having IRB professionals and researchers working together to address ROR at the local level can also inform development of policy at the national level.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Dressler LG . Disclosure of research results from cancer genomic studies: state of the science. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4270–4276.

Green ED, Guyer MS ; National Human Genome Research Institute. Charting a course for genomic medicine from base pairs to bedside. Nature 2011;470:204–213.

Couzin-Frankel J . Human genome 10th anniversary. What would you do? Science 2011;331:662–665.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:219–248, 211.

Wolf SM, Paradise J, Caga-anan C . The law of incidental findings in human subjects research: establishing researchers’ duties. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:361–383, 214.

Juengst ET . Human genome research and the public interest: progress notes from an American science policy experiment. Am J Hum Genet 1994;54:121–128.

Clayton EW . Incidental findings in genetics research using archived DNA. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:286–291, 212.

Cho MK . Understanding incidental findings in the context of genetics and genomics. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:280–285, 212.

Dressler LG, Juengst ET . Thresholds and boundaries in the disclosure of individual genetic research results. Am J Bioeth 2006;6:18–20; author reply W10–12.

Ravitsky V, Wilfond BS . Disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth 2006;6:8–17.

Ossorio PN . Letting the gene out of the bottle: a comment on returning individual research results to participants. Am J Bioeth 2006;6:24–25; author reply W10–22.

Dressler L . Biobanking and disclosure of research results: addressing the tension between professional boundaries and moral intuition. In: Solbakk JH, Holm S, Hoffman B (eds). The Ethics of Research Biobanking. Springer: New York, 2009:85–99.

Shalowitz DI, Miller FG . Disclosing individual results of clinical research: implications of respect for participants. JAMA 2005;294:737–740.

Shalowitz DI, Miller FG . Communicating the results of clinical research to participants: attitudes, practices, and future directions. PLoS Med 2008;5:e91.

Clayton EW, Ross LF . Implications of disclosing individual results of clinical research. JAMA 2006;295:37; author reply 37; author reply 38.

Bookman EB, Langehorne AA, Eckfeldt JH, et al. ; NHLBI Working Group. Reporting genetic results in research studies: summary and recommendations of an NHLBI working group. Am J Med Genet A 2006;140:1033–1040.

Fernandez CV, Weijer C . Obligations in offering to disclose genetic research results. Am J Bioeth 2006;6:44–46; author reply W10–42.

Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3:574–580.

Knoppers BM, Joly Y, Simard J, Durocher F . The emergence of an ethical duty to disclose genetic research results: international perspectives. Eur J Hum Genet 2006;14:1170–1178.

Kohane IS, Mandl KD, Taylor PL, Holm IA, Nigrin DJ, Kunkel LM . Medicine. Reestablishing the researcher-patient compact. Science 2007;316:836–837.

National Institute of Health (NIH). Points to Consider for IRBs and Institutions in their Review of Data Submission Plans for Institutional Certifications Under NIH’s Policy for Sharing of Data Obtained in NIH Supported or Conducted Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS), 2007; 13. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/gwas/gwas_ptc.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2011.

Meacham MC, Starks H, Burke W, Edwards K . Researcher perspectives on disclosure of incidental findings in genetic research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2010;5:31–41.

Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Edwards KL, Starks H, Wiesner GL ; GRRIP Consortium. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a national survey of professionals involved in human subjects protection. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2010;5:83–91.

Edwards KL, Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, et al. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a survey of human genetics researchers. Public Health Genomics 2011;14:337–345.

Patton M . Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 3rd edn. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2002.

Guba EG . Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Edu Commun Technol 1981;29:75–91.

Lincoln Y, Guba A . Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, 1985.

Charmaz K . Coding in Grounded Theory Practice. Constructing Grounded Theory - A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage: London, 2006:42–71.

Strauss A, Corbin J . Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1990.

Denzin NK . The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989.

National Institutes of Health. OPRR. Human Genetic Research. OPRR. Protecting Human Research Subjects. Institutional Review Board Guidebook 1993. http://www.genome.gov/10001752. Accessed 15 June 2011.

National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC). Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance. Volume 1: Report and Recommendations of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 1999. http://bioethics.georgetown.edu/nbac/hbm.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2011.

Kohane IS, Masys DR, Altman RB . The incidentalome: a threat to genomic medicine. JAMA 2006;296:212–215.

Wolf SM, Kahn JP, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA . The incidentalome. JAMA 2006;296:2800–2801; author reply 2801–2802.

Heaney C, Tindall G, Lucas J, Haga SB . Researcher practices on returning genetic research results. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2010;14:821–827.

Wolf LE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM, Pollack LM, Lo B . IRB chairs’ perspectives on genomics research involving stored biological materials: ethical concerns and proposed solutions. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2008;3:99–111.

Dressler L ; National Cancer Policy Board, Institutes of Medicine and Research Council of the National Academies. Human Specimens, Cancer Research and Drug Development: How Science Policy Can Promote Progress and Protect Research Participants, 2005. http://www.iom.edu/CMS/3798/12774/26207.aspx.

Miller FG, Rosenstein DL, DeRenzo EG . Professional integrity in clinical research. JAMA 1998;280:1449–1454.

Burke W, Diekema DS . Ethical issues arising from the participation of children in genetic research. J Pediatr 2006;149(1 suppl.):S34–S38.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Debra Skinner for her helpful discussions and guidance related to the methods. Dr Skinner is the director of the Methods Core of the University of North Carolina’s Center for Genomics and Society. This study was supported by funding from the NHGRI ELSI program of the Centers of Excellence in Ethical, Legal and Social Implications of Genetic Research, University of Washington, Seattle (P50HG3374); Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio (P50H3390); and the University of North Carolina (P50 HG4488) and the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy.

The Genetic Research Review Issues Project (GRRIP) is a collaborative, multisite consortium examining genomic researchers’ and IRB professionals’ views, positions, and perspectives on several aspects of the review and conduct of human genomic research. Additional members include Jo Boughman, American Society of Human Genetics, Bethesda, MD; Wylie Burke, University of Washington, Seattle; Karen Edwards, University of Washington; Seattle; William Freeman, Northwest Indian College, Bellingham, WA; Mary Quinn-Griffin, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; Amy Lemke, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Patricia Marshall, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; Pearle O’Rourke, Partners HealthCare Systems, Boston, MA; Susan Brown Trinidad, University of Washington, Seattle.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Human Genome Research Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dressler, L., Smolek, S., Ponsaran, R. et al. IRB perspectives on the return of individual results from genomic research. Genet Med 14, 215–222 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.10

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

To disclose, or not to disclose? Perspectives of clinical genomics professionals toward returning incidental findings from genomic research

BMC Medical Ethics (2021)

-

Return of genetic and genomic research findings: experience of a pediatric biorepository

BMC Medical Genomics (2019)

-

Engaging Hmong adults in genomic and pharmacogenomic research: Toward reducing health disparities in genomic knowledge using a community-based participatory research approach

Journal of Community Genetics (2017)

-

Management and return of incidental genomic findings in clinical trials

The Pharmacogenomics Journal (2015)

-

Ethical and legal implications of whole genome and whole exome sequencing in African populations

BMC Medical Ethics (2013)