Abstract

Purpose

Anterior approach white line advancement presents a novel surgical option for correction of blepharoptosis. The technique draws on several advantages of other approaches. The aim of this study was to present outcomes using this technique at a minimum follow-up of 18 months.

Patients and methods

Participants having undergone anterior approach white line advancement ptosis correction at a single institution were retrospectively recruited at a minimum of 18 months’ follow-up. A total of 18 independent eyelid measurements were recorded at final review. Outcomes included long-term rate of surgical success, upper eyelid margin-reflex distance (MRD1) at both early and late post-operative follow-up, inter-eyelid asymmetry, complications, re-operation rate, patient satisfaction, and quality-of-life improvement using the Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI). Pre- and post-operative MRD1, as well as inter-eyelid asymmetry, were compared using a two-tailed t-test.

Results

In total, 82 eyelids of 47 participants were included with a mean follow-up of 2.3 years (range 1.5–3.7). Surgical success was achieved in 91.5%, with a final mean MRD1 of 3.5 mm (95% confidence 3.2–3.7). An increase of 2.4 mm (2.1–2.8) in eyelid height was observed between baseline and long-term follow-up (P<0.0001). No significant change was observed between early and late post-operative follow-up. Pre-operative asymmetry was reduced from 1.0 mm (0.7–1.3) to 0.4 mm (0.3–0.5; P<0.0001). Patient satisfaction was 95.7% with a mean GBI score of +21.8 (13.2–30.3).

Conclusions

Anterior approach white line advancement presents an excellent option for patients undergoing ptosis correction with favourable long-term results. Comparisons are made with other techniques with respect to anatomical, functional, and surgical factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past century, there has been no shortage of techniques proposed and modified for correcting blepharoptosis.1, 2 This reflects the complexity of ptosis surgery, with consensus yet to be reached among surgeons. Broadly speaking, the modern surgeon has at his or her disposal a choice of two principles for correcting mild-moderate ptosis: advancement of the levator aponeurosis or resection of Müller’s muscle. The advantages and disadvantages of each can be largely classified as relating either to the surgical approach (‘anterior’ transcutaneous versus ‘posterior’ transconjunctival) or the anatomical and physiological effects that they bring about. Although common posterior approaches involve Müllerectomy, it is suggested that this disrupts the regulatory role played by Müller’s muscle in maintaining involuntary levator contraction.3, 4 Furthermore, the relationship between Müller’s muscle resection and ptosis correction is complex, the degree of lid heightening is limited, and its success may actually lay primarily in the advancement of the Müller’s muscle stump where it arises from the underside of the levator aponeurosis.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 For these reasons, many surgeons advocate an anterior approach, which has the logical advantage of addressing the underlying etiology by advancing the dehisced levator aponeurosis.12, 13, 14, 15 In a UK survey, >80% of oculoplastic surgeons employed an anterior approach.16 This is typically achieved by dissecting the orbital septum to expose the anterior plane of the aponeurosis, beneath the pre-aponeurotic fat pad. This approach has its own drawbacks: first, the septum and preaponeurotic fat likely have an important role in upper eyelid and periorbital cosmesis; second, the anterior fibres of the aponeurosis are weak and predominantly continuous with the orbital septum superiorly, in contrast with the posterior aponeurotic fibres, which are stronger and insert into the superior tarsus.17 It is speculated that both factors might promote a less predictable eyelid height and aesthetic outcome.15, 18 Malhotra et al5, 19 recently described advancement of the aponeurotic sheet (the white line) from a posterior approach, with encouraging results. However, some conjunctival inflammation and scarring is inevitable with any conjunctival breach. This exacerbates ocular surface irritation post-operatively.20, 21 The other disadvantage of a transconjunctival approach is that an additional incision is required to perform concurrent blepharoplasty. Indeed, skin blepharoplasty is indicated in more than half of cases where transconjunctival ptosis correction is performed.5, 15

In 2014, the senior author (BTP) first presented a novel technique for ptosis correction to the British Oculoplastic Surgical Society.22 This technique (described herein) permits advancement of the posterior aponeurotic fibres to the tarsus through a skin crease incision, without disruption to the orbital septum, pre-aponeurotic fat, or conjunctiva, and avoiding resection of Müller’s muscle. It has been performed more than 600 times at the author’s institution since 2009 and has gained growing popularity around the United Kingdom since. The aim of this retrospective study was to report the long-term outcomes (minimum of 18 months’ follow-up) of this technique.

Materials and methods

Surgical technique

Video available online in Supplementary Material.

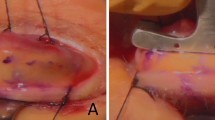

All cases were performed under local anaesthesia without sedation, except for one case under general anaesthesia, with the following standard technique. The mid-pupil position on the upper eyelid margin and desired skin crease is marked with gentian violet. A standard pinch technique is used to mark the upper extent of skin blepharoplasty when clinically indicated. Following povidone-iodine preparation, ~0.75 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200 000 adrenaline is infiltrated subconjunctivally, just superior to the upper border of the tarsal plate, followed by 1–2 ml subcutaneous infiltration along the skin crease. An upper eyelid traction suture is placed at the pre-marked mid-pupillary position on the eyelid margin to aid with dissection. A protective corneal shield can be used if desired to prevent inadvertent damage to the ocular surface. A skin crease incision is made with a number 15 Bard–Parker blade. An upper eyelid skin and partial orbicularis muscle blepharoplasty is performed if indicated. All further dissection is performed using high-temperature handheld cautery (AA01 high-temp fine-tip, 1204 °C, Bovie Medical Corporation, New York, NY, USA, or equivalent). The superior third of the tarsal plate is exposed by inferior dissection from the skin crease. Any residual strands of the levator insertion are reflected superiorly from the anterior tarsus (Figure 1a) and the dissection is continued proximally in the pre-Müller muscle plane until the underside of aponeurotic sheet becomes visible as a white line (Figure 1b). Using high-temperature cautery, Müller’s muscle is freed from the underlying conjunctiva, starting at its insertion to the superior tarsus and dissecting up to its origin on the posterior surface of the aponeurosis (Figure 1c). Inferior traction on Müller’s muscle is applied to create a fold in the levator aponeurosis at the point of Müller’s origin, which provides a useful landmark for suture placement in most patients (Figure 1d). In cases where additional lid heightening is required, dissection may continue in the plane posterior to the Müller–levator complex, beyond the origin of Müller’s. A single-armed 6/0 monofilament polybutester (Novafil, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) suture is placed through the underside of the aponeurosis either at Müller’s origin or beyond and attached to the tarsal plate ~2 mm below its upper border in a single wide half thickness bite (Figure 1e). The suture is tied on temporary knot, and eyelid height and contour are checked. Eyelid height may be adjusted by replacing the suture either higher or lower on the posterior surface of the aponeurosis, lower on the anterior tarsal plate, or loosened into a ‘hang-back’ suture.23 Polybutester is used to avoid the granulomatous reaction observed with absorbable polyglycolic acid (Vicryl, Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ, USA) sutures.24 The skin is closed with a continuous 6/0 polybutester suture, including bites into the free inferior part of Müller’s muscle to reform the skin crease. This suture is removed one week post-operatively.

Participants and recruitment

Consecutive patients that had undergone ptosis surgery using the described technique at The Royal Bournemouth Hospital between January 2012 and May 2014 were invited to participate. Participants were excluded if they had a levator function (LF) of <8 mm, a history of congenital, myogenic or neurogenic ptosis, or prior ptosis surgery. Approval for recruitment and all study procedures was gained from the host institution’s research and innovation directorate. Based on a 5% margin of error and 95% confidence level, 82 eyelids would be needed to estimate the success rate for the 138 eyelids operated on within the pre-specified study period.

Study measures

Case note review was used to record age, sex, LF and operative details, as well as pre-operative and early post-operative (1–2 weeks) upper margin-reflex distance (MRD1). All participants attended a dedicated research clinic and, after obtaining informed consent, were examined by three independent ophthalmologists, each recording the participant’s MRD1 and LF in each eye, as well as a subjective assessment of whether the eyelid contour was satisfactory. A digital photograph was taken of each participant by a trained ophthalmic photographer in a frontal plane, at a standardised distance. During post-hoc analysis of the digital images, the MRD1 for each eye was calculated by three independent observers, each taking three repeated measurements from the mid-pupillary point to the upper lid margin (a), and to the lower limbus (b) in pixels. The MRD1 in millimetres was calculated as 5.85 × a/b (assuming that the mean vertical white-to-white corneal diameter is 11.7 mm25). The final ‘late post-operative MRD1’ for each eye was calculated as a mean of all 18 independent measurements (9 clinical and 9 from photographs). Surgical success was defined for each eyelid by a late post-operative MRD1 ≥2 and ≤5.0 mm, an inter-eyelid height asymmetry ≤1 mm, and a satisfactory eyelid contour reported by all three clinicians. Secondary outcomes included early and late post-operative MRD1 and the difference between pre- and late post-operative MRD1. Other post-operative complications were recorded. Patient reported outcome measures included both the Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI)26 and a four-point scale of patient satisfaction (graded as ‘completely satisfied’, ‘significant improvement’, ‘no change’, or ‘worse than before surgery’).

Results

In total, 79 potential participants were identified as eligible for study inclusion. Of these, 52 patients (65.8%) agreed to participate. At the study visit, a further five were identified as ineligible (two previous ptosis surgery, one congenital ptosis, one myogenic ptosis, and one neurogenic ptosis). The mean participant age was 68.8±13.5 (range 13–86), 66.0% were female, and all but one were of a White ethnicity (one Asian patient). This is in keeping with the demographics of the study institution’s catchment area. Of the 47 participants, 36 (76.6%) had bilateral ptosis correction. One patient who underwent bilateral surgery had one eyelid excluded due to a unilateral neurogenic diagnosis (Bell’s palsy). The baseline and operative characteristics of all 82 operated eyelids are outlined in Table 1.

Long-term operative success

Early and late post-operative outcomes are detailed in Table 2. The overall long-term success rate as per the strict pre-defined criteria was 86.6%. On review of the ‘unsuccessful’ eyelids, four cases warrant special consideration and led to an adjusted long-term success rate of 91.5%. First, one of the ‘unsuccessful’ eyelids showed asymmetry with the contralateral, surgically naive eyelid, which was ptotic secondary to a Bell’s palsy and brow ptosis; the operated eyelid was otherwise within the criteria for success and the patient was satisfied. The patient declined surgery in the contralateral eyelid and so the operated eye was re-defined as successful; second, three patients underwent bilateral surgery, where one eyelid met the criteria for successful height at follow-up, but the other eyelid did not. In all three cases, both eyelids were originally classified as unsuccessful; one eyelid being deemed unsuccessful only due to asymmetry with the ‘failed’ eyelid. In these cases, it was considered more appropriate that only the ‘failed’ eyelid should be classified as unsuccessful. Of those eyelids that did not meet the criteria for surgical success (n=7), 4 were under-corrected (mean increase in MRD1=1.0 mm; SD=0.6; range=0.4–1.7), and 3 were over-corrected (mean increase in MRD1=2.8 mm; SD=0.4; range 2.7–2.9).

Change in eyelid height

Figure 2 demonstrates the pre-operative, early post-operative, and late post-operative eyelid height; using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, there was a significant increase in eyelid height (MRD1) of 2.4 mm (95% CI 2.1–2.8; P<0.0001) between baseline and at a mean of 2.3 years (range 1.5–3.7) follow-up. Eyelids were also more symmetrical post-operatively, with a reduction in pre-operative inter-eyelid asymmetry of 0.6 mm (95% CI 0.4–0.7; P<0.0001). Most eyelids (93.9%) underwent concurrent skin blepharoplasty. The mean increase in MRD1 in those eyelids with blepharoplasty was 2.5 mm versus 2.1 mm in those without (P=0.34). A small reduction (mean 0.3 mm) in eyelid height between the early and late post-operative period can be observed in Figure 2. The 95% confidence limits for this change were −0.1 to 0.7 mm and there was no significant correlation between the duration of follow-up and the amount of change observed (Pearson’s r=0.02; P=0.9).

Eyelid height measured at baseline, in the early post-operative period and late post-operative period in patients undergoing anterior approach white line advancement ptosis correction (n=82). Early post-operative is defined as 1–2 weeks; late post-operative period is a mean of 2.3 years (range 1.5–3.7); round markers represent mean margin-reflex distance (MRD), with error bars representing the upper and lower 95% confidence limits. P-value calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test between pre-operative and late post-operative MRD.

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient benefit as evaluated by the GBI total score (and each of its subscales) is portrayed in Figure 3. A positive benefit was observed in both the total score and the general subscale, with no significant benefit in either the support subscale or physical subscale. In total, 80.9% of participants reported a positive health benefit following ptosis correction as measured by the GBI. This is in keeping with the rate of patients that were ‘completely satisfied’ (83.0%; Table 2). Of the eight patients with a negative GBI score, all were deemed to have been ‘surgical successes’ as per the specified criteria. Although 93.6% of participants were either ‘completely satisfied’ or felt there had been a ‘significant improvement’, three patients felt that there was ‘no change’; all three of these participants met the criteria for surgical success and, among these, there was a mean increase in MRD1 of 2.6 mm (SD 1.7).

Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI) total and subscale scores, measured at long-term follow-up in patients undergoing anterior approach white line advancement ptosis correction (n=47). Long-term follow-up is a mean of 2.3 years (range 1.5–3.7); round markers represent mean values with error bars marking the upper and lower 95% confidence limits.

Discussion

This series presents outcome data supporting the safety, efficacy, and reliability of a novel technique for blepharoptosis correction. Considering the importance of the underlying degenerative etiology, outcomes are presented at a minimum follow-up of 18 months and a mean of more than 2 years. In this series, >91% of ptosis corrections were deemed to be successful at long-term follow-up. This is comparable with other techniques for anterior approach levator advancement; McCulley et al27 reported a success rate of 77% in a series of over 800 patients. Over a mean follow-up of 8.2 months, Ben Simon et al15 achieved a mean post-operative eyelid height of 2.0 mm using external levator advancement and 2.6 mm when this was combined with blepharoplasty. Although not directly comparable, the 3.5 mm final eyelid height achieved in the present study is encouraging.5, 15, 18, 21 In agreement with others,5, 15, 18 the senior author (BTP) has previously found a less than satisfactory upper lid profile in a proportion of patients undergoing conventional anterior approach levator advancement. It is not clear exactly what role the septum has, but it is postulated that its relation to the thickened arcus marginalis provides a strong and evenly distributed resistance to both the concentric contraction of the pretarsal orbicularis and the posterior vector force of levator; surgical breach of the septum might disrupt the distribution of this resistance. Others have reported more satisfactory cosmetic outcomes using a posterior approach, either as a conjunctivomüllerectomy,15, 21 or posterior approach white line advancement; perhaps due to an intact septum. The presently described technique of anterior approach white line advancement allows access to Müller’s muscle and the posterior fibres of the aponeurosis without breaching the orbital septum; a satisfactory and symmetrical eyelid contour was observed in 98.8% of eyelids. It has been suggested that the posterior approach is also associated with higher rates of success in eyelid heightening; the success rate in this series is comparable to that of posterior white line advancement (87.3%5) and conjunctivomüllerectomy (92%21). There are three distinct advantages of this technique over posterior approach surgery: first, no breach of the conjunctiva is necessary, reducing the risk of ocular surface irritation; second, concurrent blepharoplasty is indicated in the majority of patients in both this series and in others,20, 21 and can be performed through the same skin incision; third, the degree of eyelid elevation that can be achieved using müllerectomy is likely limited when compared with levator advancement.5 In agreement, Ben Simon et al15 observed a mean increase in eyelid height of 1.4 mm in conjuctivomüllerectomy, compared with 1.9 mm elevation in transcutaneous levator advancement; this series reports a mean increase of 2.4 mm and would be expected to restore >30% of the patient’s superior visual field.28 In keeping with other reports of ptosis surgery, the rate of any major complications is low.2

A series by Sagili18 has recently reported short-term results using a similar technique with a 90% success rate in 29 eyelids. Therein, the author describes small but significant differences from the original technique presented in 2014 (Parkin22) and described here. First, the tarsal insertion of Müller’s was left intact and only the pre-Müller plane was dissected. The presently described technique allows the advancement to be extended higher as needed without breaching the origin of Müller’s; this limits disruption to the afferent fibres within Müller’s that autoregulate involuntary levator contraction.3, 4 Furthermore, the present technique causes tightening of the Müller’s stump into the pre-tarsal space rather than leaving it in a state of low tension behind the aponeurosis. It is suggested that this has two benefits: first, it promotes long-lasting adhesions to form with the anterior lamella and anterior surface of the tarsus; second, this eccentric tightening might further enhance Müller’s autoregulatory role. A final difference between these techniques relates to the choice of suture material; the authors promote the use of polybutester due to the granulomatous reaction observed with polyglycolic acid sutures on histopathological examination.24 Despite these differences, the report by Sagili adds support to anterior approach white line advancement, within the limitations of a 6-week follow-up; peak eyelid height after ptosis surgery is generally achieved at 6 weeks, with 18% of patients experiencing eyelid lowering after this period.29 To that end, it is very reassuring that in this series, after a postoperative period of 1.5–3.7 years, eyelid height was maintained. Equally encouraging is that even after this timespan, patients recall the positive benefit that surgery has had on their life, as evaluated using the GBI. This patient-reported scale measures post-operative change in general and psychosocial well-being, as well as support and physical function. It was originally validated for use in otorhinolaryngological patients and although its use in ptosis surgery has been reported,30, 31, 32 validity data in the currently studied population is limited. Despite the risk of response bias inherent in its design, the GBI is a generic and translatable instrument that can measure both positive and negative impact (scored from +100 to −100) across a range of procedures;32, 33 it has been shown to correlate with both markers of surgical success34, 35, 36 and quality of life.37 The positive score of +21.8 is comparable with previous reports for ptosis surgery, with mean total scores consistently between +21 and +25, adding some support for its reliability in this population. In those patients where a negative GBI was observed, or where ‘no change’ was reported using the satisfaction scale, the patients’ views could not be corroborated by the surgical definition of success or by objective measures in eyelid height. In contrast, of those patients that did not meet the objective criteria for surgical success, all were satisfied, with positive GBI scores. This highlights the complex relationship between clinical outcomes and patient-reported assessment and the essential role of pre-operative counselling in managing patient expectations.

In defining surgical success, this series mirrors that of several others5, 16, 18, 27 by setting criteria for acceptable inter-eyelid asymmetry of ≤1 mm, as well as both minimally and maximally acceptable post-operative MRD1. Others have arbitrarily set the upper limit of acceptable MRD1 as 4.5 mm. Given that the population served by this study’s institution are almost entirely of a White ethnicity, it was deemed that having an upper acceptable limit of <5 mm would be unjustified; an MRD1 of 5 mm still leaves the lid margin below the level of the limbus25 and is entirely in keeping with normal measurements in White ethnic groups.38 In this study, there were seven eyelids with a late post-operative MRD1 between 4.5 and 5 mm, with a mean of 4.8 mm (range 4.6–5.0); the absence of any upper scleral show was verified on retrospective review of digital photographs. None of those participants had any asymmetry in eyelid height >1 mm (mean 0.3 mm) and all were ‘completely satisfied’, with a mean GBI total score of +15.5. This contrasts with the three eyelids where the MRD1>5 mm (range 5.2–5.9); these all demonstrated upper scleral show and one demonstrated an asymmetry of >1 mm with the fellow eyelid. These findings provide reassurance that in this study population, 5.0 mm is a valid and justified upper limit for acceptable MRD1. In agreement with others,5, 18, 27 2 mm was deemed an acceptable lower threshold for post-operative MRD1. There is an inverse and linear relationship between MRD1 and visual field loss that is evident as soon as the MRD1 drops below 4 mm.28 With an MRD1 of 2 mm, there is an associated loss of 12°–15° in the superior visual field, but without any encroachment on the central 30° of vision.

Limitations

This was a retrospective non-comparative series and comparing outcomes with previous reports is difficult. That said, an attempt has been made to provide the reader with as much pre- and post-operative data as possible so that this series can be put into context with others. Prospective comparative trials in ptosis surgery and are very much needed to shed light on this complex field.2 Another limitation with this study is the validity and reliability of outcome measures: it is still not clear what the relationship is between patient satisfaction and clinical measures; there is no black-and-white definition of success in ptosis surgery. This study has made a concerted effort to justify the outcome measures used. Although the limitations of eyelid measurements is recognised, their reliability has been previously demonstrated.39, 40 In this study, a total of 18 measures for MRD1 (both clinical and digital) were taken using six different observers to improve the accuracy of these outcomes. Finally, the study population was almost entirely of a White ethnic background and the results should be interpreted with caution in other ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Since the development of this technique in 2009 (and its first report in 2014 (Parkin22)), this is the only report of long-term outcomes in anterior approach white line advancement ptosis correction. The technique avoids breaching the orbital septum or conjunctiva, while still addressing the underlying aetiology of levator dehiscence. The transcutaneous approach permits skin blepharoplasty to be performed through the initial incision. Using this technique in the present series, significant increases in eyelid height were achieved with encouraging rates of success; these changes remain stable for at least 2 years. Patient satisfaction and rates of quality-of-life improvement are excellent, even at long-term follow-up. In this population, anterior approach white line advancement offers a safe, effective, and reliable option for patients undergoing correction of blepharoptosis.

References

Gonzalez MO, Durairaj VD The history of ptosis surgery. In: Cohen AJ, Weinberg DA (eds). Evaluation and Management of Blepharoptosis. Springer Science & Business Media: New York, USA, 2011 pp 5–11.

Chang S, Lehrman C, Itani K, Rohrich RJ . A systematic review of comparison of upper eyelid involutional ptosis repair techniques: efficacy and complication rates. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 129 (1): 149–157.

Matsuo K . Stretching of the mueller muscle results in involuntary contraction of the levator muscle. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18 (1): 5.

Matsuo K . Restoration of involuntary tonic contraction of the levator muscle in patients with aponeurotic blepharoptosis or horner syndrome by aponeurotic advancement using the orbital septum. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2009; 37 (2): 81–89.

Patel V, Salam A, Malhotra R . Posterior approach white line advancement ptosis repair: the evolving posterior approach to ptosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2010; 94 (11): 1513–1518.

Ben Simon GJ, Lee S, Schwarcz RM, McCann JD, Goldberg RA . Müller's muscle–conjunctival resection for correction of upper eyelid ptosis: relationship between phenylephrine testing and the amount of tissue resected with final eyelid position. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2007; 9 (6): 413–417.

Putterman AM, Fett DR . Muller's muscle in the treatment of upper eyelid ptosis: a ten-year study. Ophthal Surg 1986; 17 (6): 354–360.

Weinstein GS, Weinstein GS, Buerger Jr GF, Buerger GF . Modification of the Müller's muscle-conjunctival resection operation for blepharoptosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1982; 93 (5): 647–651.

Dresner SC . Further modifications of the Muller's muscle-conjunctival resection procedure for blepharoptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1991; 7 (2): 114.

Perry JD, Kadakia A, Foster JA . A new algorithm for ptosis repair using conjunctival Müllerectomy with or without tarsectomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18 (6): 426.

Buckman G, Jakobiec FA, Hyde K, Lisman RD, Hornblass A, Harrison W . Success of the Fasanella-Servat operation independent of Müller's smooth muscle excision. Ophthalmology 1989; 96 (4): 413–418.

Jones LT, Quickert MH, Wobig JL . The cure of ptosis by aponeurotic repair. Arch Ophthalmol 1975; 93 (8): 629–634.

Anderson RL, Dixon RS . Aponeurotic ptosis surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 1979; 97 (6): 1123–1128.

Lucarelli MJ, Lemke BN . Small incision external Levator repair: technique and early results. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 127 (6): 637–644.

Ben Simon GJ, Lee S, Schwarcz RM, McCann JD, Goldberg RA . External levator advancement vs Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection for correction of upper eyelid involutional ptosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140 (3): 426–432.

Scoppettuolo E, Chadha V, Bunce C, Olver JM, Wright M . BOPSS OBO. British Oculoplastic Surgery Society (BOPSS) National Ptosis Survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92 (8): 1134–1138.

Kakizaki H, Zako M, Nakano T, Asamoto K, Miyaishi O, Iwaki M . The levator aponeurosis consists of two layers that include smooth muscle. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 21 (5): 379–382.

Sagili S . Anterior approach white-line advancement: a hybrid technique for ptosis correction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 31 (6): 478–481.

Malhotra R, Salam A . Outcomes of adult aponeurotic ptosis repair under general anaesthesia by a posterior approach white-line levator advancement. Orbit 2012; 31 (1): 7–12.

Dailey RA, Saulny SM, Sullivan SA . Müller muscle–conjunctival resection: effect on tear production. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18 (6): 421.

Lake S, Mohammad-Ali FH, Khooshabeh R . Open sky Müller's muscle-conjunctiva resection for ptosis surgery. Eye 2003; 17 (9): 1008–1012.

Parkin B . In: The Eyelid: Video Panel–4 Ways To Do Ptosis, British Oculoplastic Surgical Society 2014 Annual Meeting (Liverpool, UK, 2014).

Meltzer MA, Elahi E, Taupeka P, Flores E . A simplified technique of ptosis repair using a single adjustable suture. Ophthalmology 2001; 108 (10): 1889–1892.

Cartmill BT, Parham DM, Strike PW, Griffiths L, Parkin Ben . How do absorbable sutures absorb? A prospective double-blind randomized clinical study of tissue reaction to polyglactin 910 sutures in human skin. Orbit 2014; 33 (6): 437–443.

Rüfer F, Schröder A, Erb C . White-to-white corneal diameter: normal values in healthy humans obtained with the Orbscan II topography system. Cornea 2005; 24 (3): 259.

Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Browning GG . Measuring patient benefit from otorhinolaryngological surgery and therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996; 105 (6): 415–422.

McCulley TJ, Kersten RC, Kulwin DR, Feuer WJ . Outcome and influencing factors of external levator palpebrae superioris aponeurosis advancement for blepharoptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 19 (5): 388.

Cahill KV, Bradley EA, Meyer DR, Custer PL, Holck DE, Marcet MM et al. Functional indications for upper eyelid ptosis and blepharoplasty surgery: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2011; 118 (12): 2510–2517.

Tucker SM, Verhulst SJ . Stabilization of eyelid height after aponeurotic ptosis repair. Ophthalmology 1999; 106 (3): 517–522.

Maycock N, MacGregor C, Saunders DA, Parkin B . Long term patient-reported benefit from ptosis surgery. Eye 2015; 29 (7): 872–874.

Mahroo OA, Hysi PG, Dey S, Gavin EA, Hammond CJ, Jones CA . Outcomes of ptosis surgery assessed using a patient-reported outcome measure: an exploration of time effects. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 98 (3): 387–390 bjophthalmol–2013–303946–390.

Smith HB, Jyothi SB, Mahroo OAR, Shams PN, Sira M, Dey S et al. Patient-reported benefit from oculoplastic surgery. Eye 2012; 26 (11): 1418–1423.

Hendry J, Chin A, Swan IRC, Akeroyd MA, Browning GG . The Glasgow Benefit Inventory: a systematic review of the use and value of an otorhinolaryngological generic patient‐recorded outcome measure. Clin Otolaryngol 2016; 41 (3): 259–275.

Oh JR, Chang JH, Yoon JS, Jang SY . Change in quality of life of patients undergoing silicone stent intubation for nasolacrimal duct stenosis combined with dry eye syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99 (11): 1519–1522.

Jutley G, Karim R, Joharatnam N, Latif S, Lynch T, Olver JM . Patient satisfaction following endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: a quality of life study. Eye 2013; 27 (9): 1084–1089.

Ho A, Sachidananda R, Carrie S, Neoh C . Quality of life assessment after non-laser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Otolaryngol 2006; 31 (5): 399–403.

Morzaria S, Westerberg BD, Anzarut A . Quality of life following ear surgery measured by the 36-item short form health survey and the Glasgow benefit inventory. J Otolaryngol 2003; 32 (5): 323–327.

Murchison AP, Sires BA, Jian-Amadi A . Margin reflex distance in different ethnic groups. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2009; 11 (5): 303–305.

Nemet AY . Accuracy of marginal reflex distance measurements in eyelid surgery. J Craniofac Surg 2015; 26 (7): e569–e571.

Boboridis K, Assi A, Indar A, Bunce C, Tyers AG . Repeatability and reproducibility of upper eyelid measurements. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85 (1): 99–101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Eye website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schulz, C., Nicholson, R., Penwarden, A. et al. Anterior approach white line advancement: technique and long-term outcomes in the correction of blepharoptosis. Eye 31, 1716–1723 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.138

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.138