Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the demographics, visual impairment, and diagnoses of patients presenting to Vision Care for Homeless People (VCHP), Crisis clinics for London’s under-researched homeless population.

Patients and methods

Two hundred eighty-three patients records, including data on sociodemographic, diabetic status, visual acuity, and ocular examination, via a comprehensive eye test were reviewed from the VCHP clinics held at 10 London ‘Crisis at Christmas’ centres in 2014.

Results

Two hundred eighty-three individual patients were seen at the VCHP clinics. Eighty-nine percent of patients were male and 11% were female. Thirty-two percent (90) patients had an ocular pathology. Lens problems, including cataracts (7%), vitreoretinal (6%), ocular motility (5%), and external eye disease (5%), were the four most common pathologies. In total, 6.4% of the patients reported that they were diabetic and a medical referral letter was given to 10% of the patients seen. Two hundred thirty-three were dispensed glasses (82%). Readers were most common (39%), then distance (28%), bifocals (15%). Presenting visual impairment was 12% in the patients tested. After refractive correction, this dropped to 2.5%.

Conclusion

This study shows that there is a high prevalence of uncorrected refractive error among patients attending the Crisis for Christmas eye clinic. These data also show high prevalence of ocular pathology. There is a clear need for the provision of eye tests and spectacles to tackle the issues and prevent visual impairment. More research and eye care services are needed to investigate how this is linked to their living status and enable this vulnerable population to transition out of homelessness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Homeless persons represent one of the most vulnerable groups within our society. It not only includes rough sleepers seen on the streets, but also the ‘hidden homeless’, those who stay in environments such as squats (unlawfully inhabited buildings) or live fulltime on a friend’s sofa. This group has an increased risk of a variety of physical illnesses,1 but also suffers disproportionately from mental health problems and higher rates of drug and alcohol use.2 Statistics tell us that homelessness is on the rise year on year. Nearly 8000 people slept rough at some point in London during 2014, doubling the figure that was reported in 2010. With it becomes a burgeoning public health concern.3, 4

It is well researched that homelessness is linked to a wide range of morbidities, however, there is relatively little on their ocular health. A study in Canada concluded that homeless persons do have higher prevalence of visual impairment, reporting 25% with vision problems, four times higher than the general population in Toronto.5 The study points to inequality and poor access to eye care as the main cause of the difference. Visual impairment has been shown to be heavily linked to lower well-being and reduced earning potential, therefore, poor vision has important implications for those experiencing homelessness.6 It is the seemingly modest tasks such as reading and completing job application forms that can make all the difference when tackling homelessness. However, the majority of homeless and vulnerable people are not in receipt of financial benefits, so are not eligible for an NHS eye examination and voucher towards their spectacles. For the few that are, few practices will make spectacles totally free of charge, and even a small charge may be unmanageable.

Since 1972, the charity Crisis runs ‘Crisis at Christmas’ centres in London providing food, shelter, and companionship during the festive period. They offer supportive healthcare services, including vision clinics run by the charity ‘Vision Care for Homeless People (VCHP)’.7 Volunteer opticians and ophthalmologists run full eye tests and examinations with donated equipment providing glasses and referrals to those in need. The VHCP clinics provide a free eye test and spectacles to homeless people who require them. The ‘Crisis at Christmas’ clinics are an extension of the weekly clinics focusing on homeless persons throughout the UK.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of visual impairment in patients at the vision clinics and conclude whether there is a link between homelessness and poor ocular health. The focus was on 10 London Crisis centres analysing patient record cards completed by volunteer ophthalmic health professionals. We hope this research highlights the need for more focus on this vulnerable group to help more people take steps out of homelessness.

Materials and methods

Crisis at Christmas 2014 was held from 22–29 December at 10 homeless shelters around London. The centres were open to the public. This study included all visitors to the 10 vision clinics during this period. In total, 283 patients were seen and provided the basis for this research. The sample size of 283 was the total number of patients that were seen and recorded during the Crisis at Christmas period. All patients that were recorded as being seen during the period were included in the study.

Sociodemographic data including gender and date of birth was collected. Past health problems with a focus on ocular history was taken from every patient. All patients were examined by a qualified optometrist who undertook an eye examination according to General Optical Council and College of Optometrist guidelines. The clinic measured visual impairment and blindness with unaided visual acuity using a LogMar Chart with Snellen scoring. As recommended by WHO, presenting acuity rather than best corrected visual acuity was used to analyse visual impairment as this reflects the reality homeless persons are living through (Table 1). Low vision was defined by categories 1 and 2. Blindness was defined by categories 3, 4, and 5. Therefore, visual impairment is defined in this study as a presenting visual acuity of worse than 6/18 in the best eye. Retinoscopy was performed by trained opticians and prescriptions were supplied for patients. Emmetropia is defined as a prescription between −0.25 and +1, myopia as less than −0.25, and hyperopia as greater than +1. High refractive error was defined as greater −/+6. Intraocular pressures were also measured with a non-contact tonometer.

Research ethics approvals were obtained from Crisis at Christmas Research and Evaluation Team and the Board of Trustees at the VHCP charity.

Results

The number of persons surveyed in this study are estimated to be 0.6% of the total homeless population in London. This was calculated from the number of rough sleepers, the available beds for homeless people in London, and an estimation of the proportion of the hidden homeless from Crisis UK.8 Of the 283 patients records, 253 (89%) were male and 30 females (11%). Age was recorded for 281 of the patients seen; date of birth was not recorded for two patients. The average presenting age was 49 years old with a range between 20 and 86. In total, 6.4% of the patients reported that they were diabetic. These demographics reflect current UK statistics.9

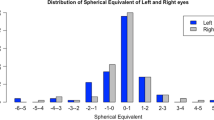

After the eye test was completed, if required, a patient had the opportunity to choose from a range of frames and order glasses. Eighty-two percent of patients were dispensed a brand new pair of glasses to improve their eye sight. From those dispensed glasses, readers were most common (39%), then distance spectacles (28%), and finally bifocals (15%). In total, 557 prescriptions were completed. Emmetropia made up 51% of eyes tested. Myopia and hyperopia were seen at 29% and 20%, respectively. High refractive error, defined as greater −/+66, was at 2%.

In total, 278 eyes had their intraocular pressure measured. The average was 15 mm Hg. Seventeen eyes were over 21 mm Hg requiring further examination according to guidance on the referral of Glaucoma suspects by community optometrists.10

Visual acuity was measured for 98% of the patients. The remaining patients refused to be examined. Presenting visual impairment was 12% in the patients tested as shown in Table 2. Categories are illustrated in Table 1. After correction, this dropped to 2.5%. Therefore, 85% of patients (27 out of 33) can be said to have uncorrected refractive error causing their visual impairment.

From 281 patients examined during the clinics, 32% (90) patients had an ocular pathology. In total, 562 eyes were examined and 20% (127) had an ocular pathology. There was a wide range of ocular presentations seen in the patient population, 39 in total. Table 3 illustrates the pathologies by category. Lens (including cataract), vitreoretinal, external eye disease, and ocular motility pathologies were the four most common. A hospital referral letter was given to 10% of the patients seen as a result of the clinical examination.

Discussion

Visual impairment was reported at 12% in presenting patients at the Crisis at Christmas VCHP clinics although these people live in a society that eye care is readily available. Presenting visual impairment in this sample is higher than the general population living in London (2%).11 Moreover, after correction visual impairment drops to 2.5%, close to the general population. Therefore, there is a high prevalence of uncorrected refractive error in patients visiting the clinic causing visual impairment. Ocular pathology is also higher than seen in the general population. This is consistent with other studies in homeless ocular health1 and ads to studies showing significant health issues in the homeless population.

Glasses were dispensed to 82% of the patients having an eye test. In addition, 10% of patients were referred for further medical investigation due to the pathology found. The Optical Confederation reports 3.6% of eye tests resulted in referrals to GP or hospital from UK opticians.12 This highlights the need for this important service to continue. Practitioners at homeless persons services point to several barriers to homeless people receiving eye care services, most importantly that over 50% of homeless people are ineligible for free NHS eye tests and glasses at the point of service.

As a future consideration, it would be useful to collate data on the living arrangements of patients to further investigate those visiting the eye clinics. The sample used in this study is a small percentage of the total population of homeless people in London. Due to a lot of the homeless population being defined at ‘hidden’ on friend’s sofa and bed and breakfasts, it is difficult to estimate the total population figure. There is a large gender disparity (89% male) reported in the sample. Crisis UK reports that in England, women make up 26% of clients that use homelessness services and 12% of rough sleepers in London are women.13

This study can conclude that there is a high prevalence of uncorrected refractive error in patients attending the eye clinic causing visual impairment. This highlights the need in the patients visiting the clinic for eye care services and spectacles. Due to the small sample size, it is difficult to elicit a link between homelessness and poor ocular health. However, it is clear that more research is needed into eye care in the homeless population. Homeless persons are a population that are vulnerable and need help. Better eye care and services to address visual impairment is required to empower these people to make a change and enable them transition out of homelessness. Alongside accommodation, job skills, access to opportunities and funding, mental and general health, ocular health is an important factor to give the best opportunity to tackle homelessness.

References

Homeless link The Unhealthy State of the Homelessness. Health Audit Results. Homeless Link: London, 2014, p. 3.

Martens WH . A review of physical and mental health in homeless persons. Public Health Rev 2001; 29 (1): 13–33.

Mayor Of London CHAIN Full Annual Report 2014/15. Greater London Authority: London, 2015, p. 3.

Mayor Of London CHAIN. Street to Home Bulletin 2009/10. Greater London Authority: London, 2010, p. 2.

Noel C, Fung H, Srivastava R, Lebovic G, Hwang S, Berger A et al. Visual impairment and unmet eye care needs among homeless adults in a Canadian city. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015; 133 (4): 455–460.

Taylor H . The economic impact and cost of visual impairment in Australia. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90 (3): 272–275.

Vision care charity for homeless people (Internet), 2016 (cited 27 May 2016). Available at www.visioncarecharity.org.

Crisis UK. Hidden homelessness (Internet), 2016 (cited 5 June 2016). Available at http://www.crisis.org.uk/pages/about-hidden-homelessness.html.

Diabetes: Stats and Facts. Diabetes UK: London, 2015, p 3.

The College of Optometrists and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Guidance on the referral of glaucoma suspects by community optometrists, 2010, p. 1.

Royal National Institute of Blind People. RNIB’s sight loss data tool. London custom report, 2015.

Optical Confederation. Optics at a glance 2014 (Internet), 2014 (cited 1 September 2016). Available at http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/optics-at-a-glance2014web.pdf.

Crisis UK. Homelessness amongst different groups (Internet), 2016 (cited 27 May 2016). Available at http://www.crisis.org.uk/pages/homeless-diff-groups.html.

Acknowledgements

I thank David Brown and Elaine Styles from VCHP charity for their ongoing support in undertaking this research project. Also the Research and Evaluation team, especially Tom Schlosser and Ligia Teixeira at Crisis, for their technical support. And Antigoni Koukoulli for valuable scientific guidance and ophthalmic expertise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sawers, N. The state of ocular health among London’s homeless population. Eye 31, 632–635 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.283

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.283