Abstract

The recent results of Protocol T have illustrated the efficacy of aflibercept in the treatment of diabetic macular edema. It also demonstrated that in patients with poor vision (<6/12), aflibercept offers anatomical and visual advantages over ranibizumab and bevacizumab in the first 12 months of treament. At 2 years, the difference between the three drugs decreased with patients with a better baseline VA (69–78) showing a statistically insignificant advantage for ranibizumab compared with aflibercept.These results were achieved using a pro-re nata (PRN) protocol, which was not previously studied in large phase 3 trials, VIVID and VISTA, that chose to compare the 2.0 mg dose in a monthly and bimonthly regimen. In this review article, we analyzed earlier studies such as DAVINCI and VIVID and VISTA to determine which treatment strategy offers the best results; monthly, bimonthly, or PRN. We also studied the different doses for aflibercept used in DAVINCI to determine which is more effective the 0.5 mg dose or the 2.0 mg dose. In addition, we analyzed the recent data from protocol T with regards to visual and anatomic outcomes to try to determine whether these results concur with previous studies. Finally, we discuss the role of aflibercept as a potential alternative to any diabetic macular edema regimen regardless what the primary drug used is.

Similar content being viewed by others

Aflibercept in diabetic macular edema: evaluating efficacy as a primary and secondary therapeutic option

Anti-vascular endothelial factors (anti-VEGFs) have become the standard of care in the treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME) after several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) established their efficacy compared with other treatment modalities such as laser therapy and steroids.1, 2, 3

There are currently three anti-VEGF drugs that are available for clinical practice; aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY, USA), bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA), and ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genetech, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Aflibercerpt, previously known as VEGF Trap- EYE, is a 115- kDA recombinant fusion protein consisting of the VEGF binding domains of human VEGF receptors 1 and 2 fused to the Fc Domain of human immunoglobulin-G1.4 Preclinical studies have shown that aflibercept has advantages over ranibizumab and bevacizumab that include a longer half-life, stronger binding to VEGF-A and the ability to bind placental growth factors 1 and 2 (another pro-permeability mediator).5

Both ranibizumab (Lucentis) and bevacizumab (Avastin) have been studied extensively in several large randomized controlled trials in the treatment of DME.1, 2, 6, 7 Patients treated with both drugs have shown excellent visual gains, long term stability and improved anatomy compared with grid laser treatment and steroid injections, making them the first line treatment for visual loss associated with DME.2 A study by Regnier et al8 showed that the lifetime cost of treating patients with DME in the UK was £20 019 for ranibizumab PRN and £25 859 for aflibercept using a bimonthly dosing regimen. It also demonstrated that from a UK healthcare perspective ranibizumab provides greater health gains with lower overall costs than aflibercept. In light of differences in cost, are there any significant advantages of using aflibercept over ranibizumab or bevacizumab in terms of outcomes and efficacy, especially in countries where insufficient insurance coverage exists and the primary drug of choice is bevacizumab (http://www.asrs.org/pat-survey/pat-survey-archive).

In this review of literature, we analyze the major RCTs that have studied the effect of aflibercept as a primary therapeutic choice in DME. In addition, we discuss, in theory, alternative roles for aflibercept in the management of eyes with non-naïve diabetic macular edema.

Aflibercept as a primary therapy

The DAVINCI Study

The DAVINCI study was a phase 2 clinical study that aimed at comparing between different doses/regimens of VEGF Trap- Eye (aflibercept) and laser photocoagulation.9, 10 221 patients were enrolled and were divided into five groups; 0.5 mg VEGF Trap-Eye every 4 weeks (0.5q4); 2 mg VEGF Trap-Eye every 4 weeks (2q4); 2 mg VEGF Trap-Eye for three initial monthly doses and then every 8 weeks, (2q8); 2 mg VEGF Trap-Eye for three initial monthly doses and then on an as-needed basis (2 PRN); or macular laser treatment using the modified ETDRS protocol. A summary of the major baseline criteria and results from the DAVINCI study are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

All groups were matched with regards to age, gender, ethnicity as well as baseline BCVA, and central retinal thickness (CRT). However, the 2q8 group had a higher prevalence of type 1 diabetes and a larger number of patients with a history of proliferative diabetic retinopathy compared with other groups. More patients in the 2q8 group had previously received grid laser (66.7%) compared with the other groups (47.7% in the 0.5q4 group, 52.3% in the 2q4 group and 57.8% in the 2PRN group). CRT ranged from 246 to 450 μm and mean visual acuity ranged from 57.6 to 59.9 EDTRS letters.

Outcome

At 24 weeks, the aflibercept groups showed an overall increase in visual acuity of + 8.5 to +11.4 letters compared with +2.5 in the laser group. 34, 32, 17, and 27% of patients in the 0.5q4, 2q4, 2q8, and 2 PRN groups, respectively, had a 15-letter improvement compared with 21% in the laser treated group. No patients in the 2 mg group lost more than 15 letters compared with 9.1% and 4.5% in the laser treated and 0.5 mg groups, respectively. There was a significant difference between each of the aflibercept groups and the laser group at 24 weeks both in terms of visual gains and percentage of patients achieving >15-letter gains.

At 52 weeks there was an overall increase in visual acuity of +9.7 to +12 letters in the aflibercept groups compared with −1.3 letters in the laser treated group. There was a significant difference between the 0.5q4, 2q4, and PRN aflibercept groups and the laser group but not the 2q8 group, which showed no significant difference. The percentage of patients achieving 15-letter gains was 40.9%, 45.5%, 23.8%, and 42.2% in the 0.5q4, 2q4, 2q8 and 2 PRN groups, respectively, compared with 11.4% in the laser group. At 20 weeks there was a steep decline in the visual acuity gains in the laser group from approximately +4 letters at week 20 to −1.3 letters at week 52. Although no explanation was given, we postulate that this drop coincided with the second laser re-treatment. If the laser group had continued on the same trajectory pre 20 weeks, the final visual outcomes in the laser group at 52 weeks might have been higher.

There were similar changes in the CRT that showed statistically significant reductions in CRT in the aflibercept groups compared with the laser groups at week 52 (P<0.0001). Both the 2q8 group and the 2PRN groups showed similar reductions in CRT approximately −175 μm, whereas the 2q4 group showed the most reduction with approximately −225 μm. The 2q8 group demonstrated a ‘see-saw’ pattern in retinal thickness after the first three loading doses. This pattern was not seen in other treatment regimens indicating that it was exclusive to the 2q8 dosing group.

2q8 vs 2q4 dosing

Although the study was not powered to detect differences between the different aflibercept groups, the 2q8 group consistently showed lower visual gains compared with the other groups. At 24 weeks the 2q4 group showed the highest visual gains (+11.4 letters) followed by the PRN group (+10.3 letters). Both the 0.5q4 group and the 2q8 group achieved similar visual gains (+8.5 letters) at 24 weeks. The low visual gains achieved by the 2q8 group were evident early during the study, while these patients were receiving their first three loading doses. This led the authors to attribute these differences to different baseline criteria. The 2q8 group had a higher percentage of patients with type 1 DM and proliferative diabetic retinopathy and a recent post hoc analysis for patients that completed the RISE and RIDE study showed that the severity of diabetic retinopathy negatively affected the response to ranibizumab injections.11 In addition, the 2q8 group had received more grid laser prior to enrollement in the study (66.7%) and based on the results of protocol I that demonstrated less visual gains in the group receiving early laser it might be assumed that laser had a detrimental effect on visual gains.2 The 0.5q4 group showed similar low gains but these differences were attributed to the low efficacy of the 0.5 mg dosage.

Conclusion of DAVINCI

The visual acuity gains were the highest in the 2q4 and the PRN groups and were the least in the 2q8 and the 0.5q4 group. The low gains achieved by the 0.5 mg group were attributed to the low efficacy of the dosage. The low gains achieved by the 2q8 group, however, were attributed to poor baseline criteria. The PRN group achieved high visual gains that parallel those of the monthly dosing group with an average of 7.4 injections, similar to the 7.2 injections needed by the 2q8 group.

VIVID and VISTA

VIVID and VISTA were two phase 3, double-masked, randomized trials that aimed to compare vascular endothelial factor blockade and laser for the treatment of diabetic macular edema.12 They also aimed at comparing between monthly and bimonthly dosing for intravitreal aflibercept (IAI). Table 2 shows the differences between VIVID/VISTA and DAVINCI both in terms of study design as well as outcomes.

VIVID recruited 466 patients and VISTA recruited 406 patients with center involving macular edema and were divided into 3 groups; 2 mg IAI every 4 weeks (2q4), 2 mg every 8 weeks (2q8) and a laser treated group.

Visual outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was change in BCVA at 52 weeks. In both VIVID and VISTA there was a significant improvement in BCVA in both the 2q4 and the 2q8 groups compared with the laser group at 52 weeks. Although the 2q4 group showed higher visual gains in both studies (+12.4 letters in VISTA and +11.2 letters in VIVID), there was no significant difference compared with the 2q8 group (+10.7 letters in VIVID and VISTA), indicating the efficacy of both dosing protocols. In addition, these visual gains were maintained through 100 weeks of follow up.12 It was also observed that the visual gains achieved at 52 weeks by the 2q4 group in VIVID (+10.5 letters in the 2q4 group) were lower than the gains achieved in VISTA (+12.5 letters in the 2q4). This difference was also observed with regards to the percentage of eyes that gained >10 letters and >15 letters(41.6% in the 2q4 and 31.1% in the 2q8 vs 7.8% in the laser group (P<0.0001) in VISTA, and 32.4% in the 2q4 and 33.3% in the 2q8 group vs 9.1% (P<0.0001) in laser group in VIVID). At 100 weeks the differences in visual gains decreased between both studies.

Although no clear explanation was provided in the study, these differences might be attributed to differences in patient demographics that might have affected patient response to IAI. VIVID and VISTA were not evenly matched as there were differences in baseline criteria such as race and prior treatment with anti-VEGF, as highlighted in Table 2. More patients in VISTA (42.9%) had received prior anti-VEGF treatments compared with VIVID (8.9%) indicating that the latter had a lower percentage of patients with untreated edema. Untreated edema could translate to chronicity which might have affected response to treatment. In both the RISE and RIDE7 as well as in RESTORE,1 patients who were included in the laser treatment arm and received delayed ranibizumab showed a reduced response to the anti-VEGF. A recent post hoc analysis looked at the response to treatment in patients with and without prior anti-VEGF treatment. The study showed that at 52 weeks patients without prior anti-VEGF treatment showed higher gains of +14.1 letters in the 2q4 group and +11.0 letters in the 2q8 groups compared with +10.4 letters and +10.5 letters in the group that had received prior anti-VEGF treatment. The study, however, did not directly compare between both groups and only concluded that patients in either group showed significant visual and anatomic improvements compared with the laser group.

Anatomical changes

The changes in visual acuity were also mirrored in the CRT changes during the study, with a significantly greater reduction in the IAI groups compared with the laser group (Table 2). It was also observed that in the 2q8 group there was a fluctuation in the CRT or a ‘see-saw pattern’ that was absent in the 2q4 group. This was previously observed in the DAVINCI 2q8 group, which probably indicates that it is probably related to the dosing regimen. This see-saw pattern was observed only after patients were shifted from the monthly dosing regimen (five doses) to the bimonthly regimen. This see-saw pattern in the 2q8 was maintained throughout the 100 week follow up. It would appear that OCT fluctuations of this kind did not affect long-term outcomes and were an OCT finding. Similar findings were seen in DAVINCI where the PRN group showed no fluctuations on OCT despite this group having received similar number of injections as the bimonthly group during the first year of follow up.9

Rescue therapy

In VIVID and VISTA, the laser group was allowed to receive rescue IAI at 24 weeks. At 52 weeks, the group that received IAI rescue had a gain of 4.2 letters and 3.5 letters compared with 0.2 and 1.2 in the group that received laser alone in VISTA and VIVID respectively. At 100 weeks these gains increased to 6.3 and 5.5 letters in the rescue IAI group compared with 0.9 land 0.7 letters in the laser only group in VISTA and VIVID respectively. The modest gains at 52 weeks can probably be explained by the relatively small percentage of patients (31% in VISTA and 24% in VIVID) who were eligible for rescue therapy at 52 weeks. Patients in the laser group could receive rescue therapy in the form of fivedoses of 2 mg IAI from week 24 provided that they lost > 10 letters on two consecutive visits or > 15 letters from any previous measurement. This meant that only patients who were non responsive to laser and lost significant vision received rescue IAI, whereas paients who did not show any visual improvement were not eligible for rescue. At 100 weeks the percentage of patients receiving IAI increased to 41 and 35% in VISTA and VIVID which might explain why higher gains were achieved at the end of the study.

The IAI groups were also allowed to receive rescue laser at 24 weeks if patients lost >10 letters on two consecutive visits or >15 letters from any previous measurement. Only a small percentage of patients were eligible to receive this treatment; 5.8% in the 2q4 groups and 2.9% in the 2q8 groups in VIVID /VISTA collectively. This small percentage coupled with the poor eligibility criteria means that very few patients significantly lost vision. At 100 weeks 3.2 and 2.2% in the 2q4 groups and 0.7 and 1.5% in the 2q8 groups in VISTA and VIVID respectively, lost >15 letters.

Conclusion of VIVID/VISTA

Unlike DAVINCI, visual gains in the 2q4 group are similar to the 2q8 group at 52 weeks and 100 weeks. This can be attributed to the previously mentioned difference in baseline criteria of the 2q8 group in DAVINCI and also to the fact that the study was a phase 2 study not powered to detect differences between the different aflibercept groups. In addition, although the DAVINCI trial had shown the efficacy of the PRN dosing regimen, it was not studied in this phase 3 trial in favor of the 2q8 dosing.

DRCR protocol T- 1 and 2-year data

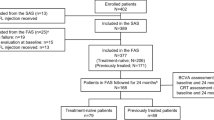

This was a randomized controlled trial13, 14 that aimed at determining the relative efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumabe initial results were published after one year with results of the planned second year extension phase being recently published.14, 15 Table 2 shows a comparison between the previous studies DAVINCI, VIVID/VISTA as well as the aflibercept arm of protocol T.

Treatment protocol

Patients were injected at baseline and then every 4 weeks. During the first 6 months, injections were deferred if patients achieved visual acuity of 20/20 (6/6) or better and had a relatively dry macula (CFT<250 μm on Zeiss Cirrus and <300 μm on Heidelberg Spectralis). However, very few patients achieved the criteria for deferment of injections, 0% in the first 3 months and ~10% in the first 6 months across the different groups. Deferred laser therapy was allowed after the first 6 months based on the results of a previous study that showed its efficacy in comparison to prompt laser.2

Protocol T is also the first major RCT that used spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) in their assessment and treatment of patients. SD-OCT has a higher sensitivity and specificity in detecting fluid as well as the ability to provide repeatable and reproducible retinal thickness measurements compared with the previously used time domain OCT (TD-OCT).16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The re-injection protocol considered worsening as an increase in central subfield thickness of 10% or more, and having reliable retinal thickness measurements is crucial for application of this protocol. In addition, a recent study using SD-OCT in patients with DME showed that its use increased the injection rate and increased the certainty of the decision making process by 36%.18

Protocol T used both OCT measurements and visual acuity in following up patients. This is similar to the protocol used in the previous DRCR study, protocol I, and has several merits.2 First, OCT alone moderately correlates with visual acuity in DME and therefore worsening or improvement in VA might not correspond to changes in thickness measurements.21 Second, the RESTORE study used a visual acuity-only strategy and the visual acuity gains achieved were less (+6 letters gain at 1 year) compared with previous DRCR.net study(+9 letters in Protocol I).1 Therefore, using a combined strategy that involves both visual acuity and OCT would seem to be the more effective strategy.

The absence of a loading dose

In VIVID and VISTA, the 2q8 group first received 5 monthly injections of IAI before starting on the bimonthly dosing regimen.22 The study did not provide clear justification as to why five initial doses were needed. The RESTORE study previously used three loading doses and the DRCR.net protocol I used four to six loading doses of ranibizumab.1, 23

Protocol T was designed to be PRN from the start and as such there were no pre-fixed loading doses. Very few patients received only three injections and most patients required more than six injections during the study. This may support the rationale used in VIVID and VISTA of five initial doses as well as the four to six initial injections used in Protocol I.2, 22 On the basis of these data, three injections might not be a sufficient loading dose and would probably under treat the vast majority of patients.1

Drug dosing used in the study

The study used the 2 mg dose of aflibercept which was found to be more effective than the 0.5 mg dose in treating DME.9 It was also used in a PRN protocol which had been previously attempted in the DAVINCI study and was found to be as effective as the 2 mg monthly dosing regimen (2q4 group).10

The 1.25 mg dose of bevacizumab was the dose previously used in the BOLT study and has proven its efficacy in treating DME.6 Compared with the 2.5 mg dose there was no difference in terms of outcomes or improvement in macular edema.24

The PRN dosing of 0.3 mg ranibizumab has not been previously tested in a large RCT.25 A PRN 0.5 mg dose has been previously tested in several large RCT and its efficacy has been established.1, 2 It is still unknown if the 0.3 mg dose is suboptimal for PRN therapy. However, the visual gains achieved by the 0.3 mg dose (+11.2 letters) in Protocol T are higher than those previously achieved by the 0.5 mg dose in previous studies; RESTORE and Protocol I. In addition, doubling the dose has not been proven to increase the efficacy of ranibizumab in in the treatment of both age related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema.26, 27 The READ-3 compared between 0.5 mg and 2.0 mg ranibizumab in the treatment of diabetic macular edema and found that after 6 months visual gains in the 0.5 mg group were higher (+9.43 letters) than the 2.0 mg group (+7.01 letters; P=0.161).28 In addition, the RISE/RIDE study found no significant difference between monthly 0.3 mg and the 0.5 mg dose of ranibizumab after 24 months of treatment.29

Baseline criteria

Patients were evenly distributed amongst the groups with 224 patients assigned to the aflibercept group, 218 in the ranibizumab group and 218 in the bevacizumab group. The groups were evenly matched with minimal differences in baseline characteristics between the different groups. However, the majority of patients were white (65%) with very few Asian patients enrolled in the study. In VIVID/VISTA, VIVID had a higher percentage of Asian patients and had lower visual gain compared with patients enrolled in VISTA who had very few Asian patients (Table 2).12 The mean visual acuity letter score at baseline was 64.8 EDTRS letters which was higher than the previous mean of 58.9 and 59.4 letters in VIVID/VISTA.

Visual outcomes

The mean improvement in visual acuity at 12 months was greater with aflibercept (+13.3 letters) than with bevacizumab (+9.7 letters) or ranibizumab (+11.2 letters) (P<0.001 for aflibercept vs bevacizumab and P=0.03 for aflibercept vs ranibizumab). At 2 years, the differences between the drugs decreased with the mean gain of +12.8 letters (aflibercept), +12.3 letters (ranibizumab), and +10.0 letters (bevacizumab). There was no longer any statistically significant differences between aflibercept and ranibizumab. However, aflibercept showed higher gains than bevacizumab at 2 years (P=0.02), but there was no significant differences between bevacizumab and ranibizumab (P=0.11).

In the first year of the study, the differences between the drugs were mainly driven by patients with a visual acuity of 20/50 or worse at baseline as there were no significant differences in patients with a visual acuity of 20/32(6/9) to 20/40 (6/12). In addition, the differences were apparent very early during the study, as early as 4 weeks, meaning that probably the efficacy of a single dose of aflibercept is higher than ranibizumab and bevacizumab.

For patients with a VA 20/50 or worse, the percentage of patients showing 15-letter improvements was 67%, 41%, and 50% in year 1 and 58%, 52%, and 55% in year 2 in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively. At 2 years there were no differences between the three drugs. In the same VA group, the mean gains at the end of 2 years were +18.1 letter, +13.3 letters, and +16.1 letters in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab, respectively. There was only a significant difference between aflibercept and bevacizumab, but none between aflibercept and ranibizumab. Patients with VA 20/40 (6/12) or better showed no differences in either 10-letter gains or 15 letters among the different treatment groups at 1 or 2 years of treatment. At 2 years, the mean gain from baseline was +7.8 letters for aflibercept, +6.8 letters for bevacizumab, and +8.6 letters for ranibizumab. There were no significant differences between either ranibizumab and aflibercept or between aflibercept and bevacizumab. With regard to letters lost there was no significant difference between the different drugs regardless of baseline visual acuity indicating that most patients do well (visually and anatomically), regardless of the drug used. It would also seem that for patients with VA 20/40 (6/12) or better, all three drugs have similar efficacy and for patients with VA 20/50 (6/15) or worse these differences are minor.

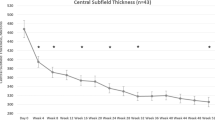

Anatomical outcomes

Unlike visual acuity gains, the anatomical differences were apparent both in the patients with VA 20/32 (6/9.5)–20/40 (6/12) and those with VA 20/50 (6/15) or worse at year 1. Aflibercept was consistently better than bevacizumab with greater mean changes in central macular thickness in both VA groups at year 1 (P=0.01) and at year 2 (P<0.001). At year 2, there were no significant differences between the mean change in central macular thickness in the aflibercept and ranibizumab groups in both VA groups (P= 0.19 in the 20/50 (6/15) or worse group and P=0.26 in the 20/32 (6/9.5)–20/40 (6/12) group).

Approximately, two thirds of all patients treated with aflibercept (70% with baseline VA worse than 20/50 and 62% with baseline VA 20/32 (6/9.5)-20/40 (6/12)) had a central subfoveal thickness (CST)<250 μm at 1 year with only a small increase at year 2 (75% in the 20/50 (6/15) or worse group and 67% in the 20/32 (6/9.5)–20/40 (6/12) group). The number of patients achieving dryness or a CST<250 μm, was significantly higher in the aflibercept group compared with bevacizumab (P<0.001) but not ranibizumab. However, a subgroup analysis showed that it was significantly higher than ranibizumab in the 20/50 (6/15) or worse VA group (P=0.02) at year 1 but not in the 20/32 (6/9.5)–20/40 (6/12) group. By year 2, this difference remained but was no longer significant in the 20/50 (6/15) or worse group (P=0.08).

It would seem that aflibercept is anatomically better than bevacizumab in all VA groups and only slightly better than ranibizumab in the 20/50 (6/15) or worse group. With no significant differences in vision at the end of 2 years whether this anatomic difference is clinically relevant has yet to be determined.

Treatment load and laser treatment

The median number of injections was similar between the three groups; 9 for aflibercept, 10 for bevacizumab, and 10 for ranibizumab (P=0.045 overall comparison) at year 1. In year 2, the median number of injections was five for aflibercept, six for bevacizumab and ranibizumab. In addition, more patients treated with aflibercept did not need laser photocoagulation (63% for aflibercept vs 44% in bevacizumab and 54% in ranibizumab; P<0.001). In the second year, the number of patients needing at least 1 session of laser was 20%, 31%, and 27% in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively. By 2 years, the number of patients needing laser in the aflibercept group was significantly less than both the ranibizumab and bevacizumab groups (P<0.001 aflibercept vs bevacizumab and P=0.04 aflibercept vs ranibizumab). This difference in the frequency of use of laser treatment may be attributed to differences in anatomical improvement between the three drugs.

PRN vs Bimonthly dosing regimens

VIVID/VISTA used five initial loading doses and Protocol T has shown that there is a percentage of patients who do not achieve a dry fovea after five doses. Switching patients to a bimonthly protocol might be premature and lead to under treatment. A recent post hoc analysis of patients enrolled in VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 found that ~33.5% of age-related macular degeneration patients had residual fluid after the first three loading doses of aflibercept.30 These patients were automatically enrolled in the bimonthly fixed dosing regimen despite having fluid.

Previous studies have shown that the number of injections decreases significantly with each year of treatment, reaching two to three injections in the second year and one to two injections in the third year.2 Using a bimonthly regimen, the estimated number of injections in the second year and third year would be five to six injections, which would also be overtreating a percentage of patients. In addition, different patients respond differently to aflibercept, some requiring as little as four to five injections in the first year and a bimonthly fixed dosing regimen would also over treat the early and good responders.15 Finally, bimonthly dosing can not be maintained indefinetly and it is expected that after 2 years of therapy patients will be shifted to PRN.

Unlike AMD, where PRN dosing is slightly inferior to monthly dosing and the need to develop strategies such as treat and extend is necessary to prevent recurrences, diabetic macular edema behaves differently and patients show similar gains with both monthly and PRN dosing.31, 32, 33, 34, 35 In addition, AMD is usually a lifelong disease with required treatment extending all the way up to 7 years or more.36 The recent data from the 5-year extension of protocol I have shown that diabetic macular edema is in fact a disease that can be managed effectively using a PRN strategy.2 Therefore, it can be suggested that bimonthly dosing is unnecessary in DME and that PRN aflibercept is very effective.

With regard to anatomy, it was noted both in DAVINCI and in VIVID/VISTA that there was a fluctuation in macular thickness or a see-saw pattern in patients using a bimonthly dosing regimen. This was absent in the PRN arms of both DAVINCI and Protocol T despite patients requiring a similar number of injections as the bimonthly group. Whether the fluctuations (see-saw pattern) indicate a reduction in drug efficacy during the 2-month interval or whether some patients were being under-treated using the bimonthly regimen has yet to be ascertained. This might lead us to conclude that a tailored treatment regimen leads to a more stable anatomic response with less patients being under or over treated and, eventually, better long-term outcomes.

Aflibercept in non-naive eyes (secondary therapy)

There have been a limited number of studies that have evaluated the effect of changing from bevacizumab to other anti-VEGFs in cases of diabetic macular edema.37, 38 This is in contrast to AMD where the effect of switching between anti-VEGFs in resistant cases has been studied extensively.39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Switching to both aflibercept and ranibizumab has been attempted, with resistant cases usually showing variable degrees of improvement, making this strategy a reasonable option in cases of AMD.

Only three recent studies looked at the effect of switching from ranibizumab or bevacizumab to aflibercept in cases of resistant DME.46, 47 The first study included 21 eyes and showed a significant decrease in CFT from 453.52±143.39 μm to 362.57±92.82 μm (P=0.001) after one injection. At the end of follow-up, the mean CFT was 324.17±98.76 μm (P=0.001). Mean visual acuity was 0.42±0.23 logMAR just prior to the switch, 0.39±0.31 logMAR after one aflibercept injection, and 0.37±0.22 logMAR at the end of follow-up. The second study47 included 14 eyes that were switched to Aflibercept after being non responsive to ranibizumab and/or bevacizumab and showed that 79% of eyes showed a 23% decrease in average central foveal thickness from 421 to 325 μm (P<0.0132). The third study included 50 eyes previously treated with ranibizumab or bevacizumab. Patients had a mean of 13.7 injections prior to conversion and it was found that although the mean VA did not significantly change post first and second injections, there was a significant improvement of macular thickness from 459.2±139 μm to 348.7± 107 μm after two injections (P<0.0001).48 This would seem to indicate that patients with chronic edema improve anatomically, however, fail to respond visually to switching between intravitreal drugs, a finding previously reflected in FAME.49

The idea of switching to aflibercept might also be supported by data from the previous VIVID/VISTA trial.12, 22 Despite 42.9% of patients in VISTA having had prior anti-VEGF therapy, the mean visual gain at 52 weeks was +12.2 EDTRS letters. This would imply that as they were being shifted from one anti-VEGF agent to another, they showed excellent visual gains that were not hampered by prior therapy.

Early switching vs late switching

Late switching Switching as a concept has been criticized mainly because of the lack of well designed RCT studying its effects. Although initial results appear to show that patients with resistant edema respond to changing therapy, the exact timing of this switch remains in question. Some recommend early switching, whereas others recommend switching late in the course of treatment to allow late responders to be identified. Proponents of late switching will argue that patients who show poor early response show a delayed response after continued treatment. In a recent post hoc analysis from RISE/RIDE patients who showed <10% decrease in macular thickness after three injections achieved similar visual acuity gains after 24 months as those who showed an immediate >10% decrease in thickness.50 Similarly, a post hoc analysis of the BOLT and DRCR protocol I studies have identified a sub group of patients defined as late responders who showed this delayed response.51, 52 In addition, a recent analysis of CATT 2-year data showed that the visual and anatomic gains achieved by AMD patients who were switched to aflibercept in several case series and prospective studies were similar to the gains achieved by the patients enrolled in CATT who were eligible for switching, but were maintained on the same drug. They concluded that these patients are part of a ‘late–responder’ group that do eventually respond with continued treatment.53

Early switching A recent post hoc analysis by Dugel et al of Protocol I has demonstrated that patients with a strong early response (≥10 letters at week 12) maintained this strong response over time and those with limited improvements after three injections (<5-letter gain) also showed limited improvement for the entire 3-year study.54 The recent publication by Rahimy et al48 showed that patients switched to aflibercept after a mean of 13 injections of bevacizumab/ranibizumab failed to show any significant visual improvements after 2 months of treatment. This would seem to suggest that patients being switched late in the course of treatment might show anatomic improvement without corresponding visual gains.

It is still unknown if patients achieving fluid resolution early show better long-term outcomes. The FAME study that looked at steroid implants in cases of chronic diabetic edema showed that despite anatomical improvements, vision did not improve.55 Patients in RISE and RIDE who were switched from laser to ranibizumab 2 years into the study failed to achieve similar visual gains.7 It is logical to consider that the longer the edema stays in the retina—however minimal it might be—the more long-term damage it will cause and a strategy that incorporates early anatomic dryness will have better long-term outcomes. This would be in favor of early switching in an attempt to reduce the edema earlier.

The most compelling evidence for early switching and anatomic dryness is perhaps a recent publication by the DRCR.56 The post hoc analysis of protocol I showed that 50% of patients treated with 0.5 mg ranibizumab had edema at 24 weeks (persistent edema group). Forty percent of patients with persistent edema had residual edema at 3 years (chronic persistent edema group) and had a mean gain of +7 letters from baseline compared with +13 letters in the group where the persistent edema had resolved at 3 years. This would seem to suggest that for those 40%, anatomic dryness would remain elusive if they were maintained on the same treatment regimen. In protocol T, patients treated with bevacizumab achieved less visual gains with more residual edema at the end of the first year (50% residual fluid vs 30% in aflibercept treated eyes). It would seem logical that the findings of the post hoc analysis of protocol I regarding chronic persistent edema would be more pronounced with bevacizumab. Therefore at least for bevacizumab treated patients, early switching might be worth exploring if the primary aim is achieving better anatomic outcomes.15, 56

Final conclusions

Aflibercept is an effective primary treatment choice for patients with DME especially for patients with VA 20/50 or worse. A higher percentage of patients achieve a dry macula after being treated with Aflibercept. A PRN regimen provides visual and anatomic outcomes similar to a monthly regimen. The bimonthly regimen, although more convenient in terms of patient visits, might over- or undertreat many patients and has not been proven to be more effective than the PRN regimen. On the other hand, the PRN regimen of protocol T had higher visual gains compared with the monthly and bimonthly arms of VIVID/VISTA.

Switching to aflibercept may be a valid option for patients being treated with alternate anti-VEGFs, especially bevacizumab, however, the exact efficacy and timing of this strategy in lieu of late responders has yet to be determined.

References

Mitchell P, Bandello F, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lang GE, Massin P, Schlingemann RO et al. The RESTORE study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2011; 118 (4): 615–625.

Elman MJ, Ayala A, Bressler NM, Browning D, Flaxel CJ, Glassman AR et al. Intravitreal Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: 5-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (2): 375–381.

Domalpally A, Ip MS, Ehrlich JS . Effects of intravitreal ranibizumab on retinal hard exudate in diabetic macular edema: findings from the RIDE and RISE phase III clinical trials. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (4): 779–786.

Holash J, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, Croll SD, Ho L, Russell M et al. VEGF-Trap: a VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99 (17): 11393–11398.

Gaudreault J, Fei D, Rusit J, Suboc P, Shiu V . Preclinical pharmacokinetics of Ranibizumab (rhuFabV2) after a single intravitreal administration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46 (2): 726–733.

Michaelides M, Kaines A, Hamilton RD, Fraser-Bell S, Rajendram R, Quhill F et al. A prospective randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy in the management of diabetic macular edema (BOLT study) 12-month data: report 2. Ophthalmology 2010; 117 (6): 1078–1086 e1072.

Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, Boyer DS, Patel S, Feiner L et al. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: the 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2013; 120 (10): 2013–2022.

Regnier SA, Malcolm W, Haig J, Xue W . Cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab versus aflibercept in the treatment of visual impairment due to diabetic macular edema: a UK healthcare perspective. ClinicoEconomics and outcomes research : CEOR 2015; 7: 235–247.

Do DV, Nguyen QD, Boyer D, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Brown DM, Vitti R et al. One-year outcomes of the da Vinci Study of VEGF Trap-Eye in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2012; 119 (8): 1658–1665.

Do DV, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Gonzalez VH, Gordon CM, Tolentino M, Berliner AJ et al. The DA VINCI Study: phase 2 primary results of VEGF Trap-Eye in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2011; 118 (9): 1819–1826.

Sophie R, Lu N, Campochiaro PA . Predictors of functional and anatomic outcomes in patients with diabetic macular edema treated with ranibizumab. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (7): 1395–1401.

Brown DM, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Do DV, Holz FG, Boyer DS, Midena E et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 100-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (10): 2044–2052.

Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Wells JA Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Glassman AR Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Ayala AR Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Jampol LM Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N Aiello LP et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015; 372 (13): 1193–1203.

Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Bressler NM, Bressler SB et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 2016; 123 (6): 1351–1359.

Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, Jampol LM, Aiello LP, Antoszyk AN et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015; 372 (13): 1193–1203.

Bressler SB, Edwards AR, Chalam KV, Bressler NM, Glassman AR, Jaffe GJ et al. Reproducibility of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography retinal thickness measurements and conversion to equivalent time-domain metrics in diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132 (9): 1113–1122.

Cukras C, Wang YD, Meyerle CB, Forooghian F, Chew EY, Wong WT . Optical coherence tomography-based decision making in exudative age-related macular degeneration: comparison of time- vs spectral-domain devices. Eye (Lond) 2010; 24 (5): 775–783.

Liu MM, Wolfson Y, Bressler SB, Do DV, Ying HS, Bressler NM . Comparison of time- and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in management of diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014; 55 (3): 1370–1377.

Nigam N, Bartsch DU, Cheng L, Brar M, Yuson RM, Kozak I et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography for imaging ERM, retinal edema, and vitreomacular interface. Retina 2010; 30 (2): 246–253.

Fiore T, Androudi S, Iaccheri B, Lupidi M, Giansanti F, Fruttini D et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of retinal thickness measurements in diabetic patients with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Curr Eye Res 2013; 38 (6): 674–679.

Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research N. The relationship between OCT-measured central retinal thickness and visual acuity in diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2007; 114 (3): 525–536.

Korobelnik JF, Do DV, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Boyer DS, Holz FG, Heier JS et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2014; 121 (11): 2247–2254.

Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Edwards AR et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010; 117 (6): 1064–1077 e1035.

Lam DS, Lai TY, Lee VY, Chan CK, Liu DT, Mohamed S et al. Efficacy of 1.25 MG versus 2.5 MG intravitreal bevacizumab for diabetic macular edema: six-month results of a randomized controlled trial. Retina 2009; 29 (3): 292–299.

Lang GE, Berta A, Eldem BM, Simader C, Sharp D, Holz FG et al. Two-year safety and efficacy of ranibizumab 0.5 mg in diabetic macular edema: interim analysis of the RESTORE extension study. Ophthalmology 2013; 120 (10): 2004–2012.

Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, Heier JS, Suner IJ, Li Z et al. Twelve-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013; 120 (5): 1046–1056.

Ho AC, Busbee BG, Regillo CD, Wieland MR, Van Everen SA, Li Z et al. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2014; 121 (11): 2181–2192.

Do DV, Sepah YJ, Boyer D, Callanan D, Gallemore R, Bennett M et al. Month-6 primary outcomes of the READ-3 study (Ranibizumab for Edema of the mAcula in Diabetes-Protocol 3 with high dose). Eye (Lond) 2015; 29 (12): 1538–1544.

Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, Boyer DS, Patel S, Feiner L et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2012; 119 (4): 789–801.

Moshfeghi DM, Hariprasad SM, Marx JL, Thompson D, Soo Y, Gibson A et al. Effect of fluid status at week 12 on visual and anatomic outcomes at week 52 in the VIEW 1 and 2 trials. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2016; 47 (3): 238–244.

Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, Dubovy SR, Michels S, Feuer W et al. A variable-dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: year 2 of the PrONTO Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2009; 148 (1): 43–58.e41.

Berg K, Pedersen TR, Sandvik L, Bragadottir R . Comparison of ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration according to LUCAS treat-and-extend protocol. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (1): 146–152.

Holz FG, Amoaku W, Donate J, Guymer RH, Kellner U, Schlingemann RO et al. Safety and efficacy of a flexible dosing regimen of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the SUSTAIN study. Ophthalmology 2011; 118 (4): 663–671.

Arnold JJ, Campain A, Barthelmes D, Simpson JM, Guymer RH, Hunyor AP et al. Two-year outcomes of "treat and extend" intravitreal therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (6): 1212–1219.

Rayess N, Houston SK 3rd, Gupta OP, Ho AC, Regillo CD . Treatment outcomes after 3 years in neovascular age-related macular degeneration using a treat-and-extend regimen. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 159 (1): 3–8.e1.

Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS, Sadda SR, Zhang K . Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 2013; 120 (11): 2292–2299.

Hanhart J, Chowers I . Evaluation of the Response to Ranibizumab Therapy following Bevacizumab Treatment Failure in Eyes with Diabetic Macular Edema. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2015; 6 (1): 44–50.

Dhoot DS, Pieramici DJ, Nasir M, Castellarin AA, Couvillion S, See RF et al. Residual edema evaluation with ranibizumab 0.5 mg and 2.0 mg formulations for diabetic macular edema (REEF study). Eye (Lond) 2015; 29 (4): 534–541.

Arcinue CA, Ma F, Barteselli G, Sharpsten L, Gomez ML, Freeman WR . One-year outcomes of aflibercept in recurrent or persistent neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 159 (3): 426–436.e422.

Aslankurt M, Aslan L, Aksoy A, Erden B, Cekic O . The results of switching between 2 anti-VEGF drugs, bevacizumab and ranibizumab, in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Ophthalmol 2013; 23 (4): 553–557.

Bakall B, Folk JC, Boldt HC, Sohn EH, Stone EM, Russell SR et al. Aflibercept therapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration resistant to bevacizumab and ranibizumab. Am J Ophthalmol 2013; 156 (1): 15–22.e11.

Batioglu F, Demirel S, Ozmert E, Abdullayev A, Bilici S . Short-term outcomes of switching anti-VEGF agents in eyes with treatment-resistant wet AMD. BMC Ophthalmol 2015; 15: 40.

Ehlken C, Jungmann S, Bohringer D, Agostini HT, Junker B, Pielen A . Switch of anti-VEGF agents is an option for nonresponders in the treatment of AMD. Eye (Lond) 2014; 28 (5): 538–545.

Fassnacht-Riederle H, Becker M, Graf N, Michels S . Effect of aflibercept in insufficient responders to prior anti-VEGF therapy in neovascular AMD. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014; 252 (11): 1705–1709.

Gharbiya M, Iannetti L . Visual and anatomical outcomes of intravitreal aflibercept for treatment-resistant neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 273754.

Lim LS, Ng WY, Mathur R, Wong D, Wong EY, Yeo I et al. Conversion to aflibercept for diabetic macular edema unresponsive to ranibizumab or bevacizumab. Clin Ophthalmol 2015; 9: 1715–1718.

Wood EH, Karth PA, Moshfeghi DM, Leng T . Short-term outcomes of aflibercept therapy for diabetic macular edema in patients with incomplete response to ranibizumab and/or bevacizumab. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2015; 46 (9): 950–954.

Rahimy E, Shahlaee A, Khan MA, Ying GS, Maguire JI, Ho AC et al. Conversion to aflibercept after prior anti-VEGF therapy for persistent diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol 2015.

Campochiaro PA, Brown DM, Pearson A, Chen S, Boyer D, Ruiz-Moreno J et al. Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts provide benefit for at least 3 years in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2012; 119 (10): 2125–2132.

Pieramici DJ, Wang PW, Ding B, Gune S . Visual and anatomic outcomes in patients with diabetic macular edema with limited initial anatomic response to ranibizumab in RIDE and RISE. Ophthalmology 2016; 123 (6): 1345–1350.

Sivaprasad S, Crosby-Nwaobi R, Heng LZ, Peto T, Michaelides M, Hykin P . Injection frequency and response to bevacizumab monotherapy for diabetic macular oedema (BOLT Report 5). Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97 (9): 1177–1180.

Bressler SB, Qin H, Beck RW, Chalam KV, Kim JE, Melia M et al. Factors associated with changes in visual acuity and central subfield thickness at 1 year after treatment for diabetic macular edema with ranibizumab. Arch Ophthalmol 2012; 130 (9): 1153–1161.

Ying GS, Maguire MG, Daniel E, Ferris FL, Jaffe GJ, Grunwald JE et al. Association of baseline characteristics and early vision response with 2-year vision outcomes in the comparison of AMD treatments trials (CATT). Ophthalmology 2015; 122 (12): 2523–31.e1.

Late Breaking Developments, Retina Subspeciality Day. American Academy of Ophthalmology: Las Vegas, Nevada, 2015.

Cunha-Vaz J, Ashton P, Iezzi R, Campochiaro P, Dugel PU, Holz FG et al. Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous implants: long-term benefit in patients with chronic diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2014; 121 (10): 1892–1903.

Bressler SB, Ayala AR, Bressler NM, Melia M, Qin H, Ferris FL 3rd et al. Persistent macular thickening after ranibizumab treatment for diabetic macular edema with vision impairment. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 278–285.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ashraf, M., Souka, A., Adelman, R. et al. Aflibercept in diabetic macular edema: evaluating efficacy as a primary and secondary therapeutic option. Eye 30, 1531–1541 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.174

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.174