Abstract

Background

Poppers are a recreational substance of abuse belonging to the alkyl nitrite family of compounds. In the United Kingdom, where they are legal to purchase but illegal to sell for human consumption, 10% of the general population have tried them. They are considered low risk to physical and mental health. Two recent case series from France demonstrated foveal pathology in individuals associated with poppers use.

Method

A case series of seven patients presenting to four hospitals in the United Kingdom with visual impairment and maculopathy associated with inhalation of poppers.

Results

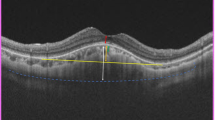

All patients experienced visual symptoms associated with poppers use. The majority had impaired visual acuity, central scotomata, distortion, or phosphenes. Clinical signs on fundoscopy ranged from normal foveal appearance to yellow, dome-shaped lesions at the foveola. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) showed varying degrees of disruption of the presumed inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction.

Discussion

Although poppers have been in use for several decades, in 2007, following legislative changes, there was a change in the most commonly used compound from isobutyl nitrite to isopropyl nitrite. There were no reports of ‘poppers maculopathy’ before this. Poppers maculopathy may be missed if patients are not directly questioned about their use. The disruption or loss of the presumed IS/OS junction on SD-OCT are a characteristic feature. Further study of maculopathy in poppers users is now needed. Raising public awareness of the ocular risks associated with their use may be necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

‘Poppers’ is a slang term referring to recreational substances of abuse belonging to the alkyl nitrite family of compounds. Inhalation of the fumes from these volatile nitric oxide (NO) donors may provide a brief sense of euphoria and sexual arousal. They have been in popular use for many years.1 In the United Kingdom, the most commonly used compound is isopropyl nitrite, which is legal to purchase, but illegal to sell for human consumption.2, 3 They are therefore marketed for alternative uses such as ‘room odourisers’ and ‘video head cleaners’. Suppliers of such products are not regulated in terms of quality control and health-related toxicities, and are not subject to narcotics drugs regulations.

Poppers are readily available for purchase online, in nightclubs, or on the high street. Ten per cent of the UK general population (aged 16–59 years) have tried poppers,3 and they are most widely used in the gay and ‘nightclubbing’ communities.4, 5 Poppers have been regarded, by scientific experts, as low risk to physical and mental health.6

The authors recently encountered seven patients with macular changes associated with poppers use. The retinal findings resemble recent case reports from France.7, 8

Case reports

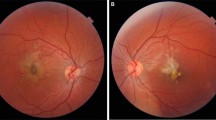

Seven adults (five males and two females) attended four ophthalmic centres in the north of England and north Wales in 2011 with visual disturbance associated with the use of poppers (Table 1). Mean age was 39.5 years (median 37). One patient was HIV positive (case 2), the others either tested HIV negative (case 1) or were untested. Symptoms included reduced visual acuity, fluctuating vision, central scotoma, photophobia, and phosphenes. Abnormal bilateral symmetrical yellow dome-shaped lesions were observed at the foveola. There was some variation in the size of the domes, with the most marked being 100 μm high and 400 μm wide. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) imaging was undertaken in all cases and abnormal architecture of the presumed junction of the inner segment and outer segment of the photoreceptors (inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction) were observed (Figure 1).

Case 2: (a) January 2010 Fundus photography (OD and OS) showing discrete yellow lesions at both fovea. (b) October 2010 SD-OCT scan showing disruption of the IS/OS junction. (c) December 2011 SD-OCT scan showing increased disruption of the IS/OS junction after a further 14 months of continued poppers use.

There was no significant ophthalmic history in any of the cases bar low myopic error (cases 1, 2, and 6). There was no concurrent medical history (excluding case 2) or family history of retinal disease.

Two patients, both gay males, were ‘long-term’ users (cases 1 and 2), who had been using poppers for 20 and 14 years, respectively, but had only noticed visual changes over the past 2 years. They were unable to specify precisely when their visual symptoms had developed, and did not associate symptoms with poppers use. Both cases took longer to diagnose (average 16 months, four appointments). Cases 1 and 2 had the lowest initial visual acuity and, in spite of significant reduction in poppers use (case 1) or complete cessation (case 2), there was no change to visual function.

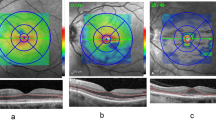

The remaining five patients (cases 3–7) were first time and one time only poppers users. They were heterosexual or sexuality was not discussed. These cases presented with acute visual symptoms associated with recent poppers use, with no further poppers use during their follow-up. Visual impairment was typically less than in the chronic poppers users, and improved following poppers discontinuation. These cases provide information regarding the temporal relationship with both development of SD-OCT findings and resolution of symptoms. Case 4 had SD-OCT performed within 24 h of poppers use and development of symptoms. Although the initial SD-OCT was normal (Figure 2a), at 3 months she had IS/OS disruption, which had partially improved by 5 months (Figures 2b and c). There was a corresponding visual improvement throughout. Cases 5 and 6 both had full visual recovery over 4 and 6 weeks, respectively.

Case 4 SD-OCT scan of the fovea (OD and OS). (a) Day 1 post inhalation of poppers and development of symptoms—retinal architecture appears normal. (b) 3 Months after inhalation of poppers—disruption of the IS/OS junction bilaterally. (c) 5 Months after inhalation of poppers—some improvement in symptoms and a reduction in the degree of IS/OS disturbance, OS more than OD. (d) 17th month, having resumed inhalation of poppers from month 6.

Discussion

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) from prescribed medications are well-recognised patient safety concerns. Ophthalmologists are often aware of ADRs from prescribed medications that can cause visual loss. Both prescribed and ‘over-the-counter’ medications are monitored in the United Kingdom by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.9 Pharmacovigilance has been harmonised across national and international boundaries.10 However, products that are not sold for human consumption (including volatile nitrites when sold as ‘room odouriser’) are not subject to such regulation or scrutiny. Thus, there is a potential health risk if such products are consumed.

Our patients’ clinical history and findings resemble the patients from France who took the same type of poppers between December 2007 and July 20107, 8 (Dr M Paques, Personal communication 2012). The majority of our patients experienced visual impairment with central scotomata, and were found to have bilateral foveal yellow spots and IS/OS junction disruption. These findings demonstrate consistency in different locations across the United Kingdom and internationally. Our cases provide additional information to the previously described maculopathy. Case 4 demonstrates that visual symptoms and acuity loss may predate OCT abnormality following poppers inhalation. Case 4 showed partial resolution at month 5 having ceased use of poppers (’Purple Haze‘ from month 3 of presentation) but was symptomatic with corresponding OCT features at month 17 review having failed to attend any review appointments in between (patient admitted having switched to twice weekly inhalation of ‘Liquid Gold’ from month 6 onward). Cases 3, 4, 5, and 7 demonstrate maculopathy after a single episode of inhalation. Case 4 shows partial resolution, and cases 5 and 6 show complete resolution of signs and symptoms. Our cases demonstrate that there may be a dose-related effect or cumulative toxicity with poppers use as cases 1 and 2, who admitted to long-term regular use, had the most severe disease and showed no sign of improvement on reduced usage or abstinence in the observation period.

Before 2010, there have only been isolated case reports of visual loss following poppers inhalation, albeit with a different clinical picture.11 Pece et al12 describe transient visual impairment to a 30-year-old male after inhalation of isobutyl nitrite, with yellowish-white spots at the fovea, which gradually improved with time. Case 1 in this series has recently been published.13 Given the long-standing use of poppers,1 the question arises as to why maculopathy associated with poppers use has not been recognised until 2010.7 Up to 2007, isobutyl nitrite was the most commonly used compound in poppers in the United Kingdom.2, 14 The Dangerous Substances and Preparations (Safety) Regulations 2006 reclassified isobutyl nitrite as a Class II carcinogen.15 Isobutyl nitrite was thus illegal to supply, in the UK, from August 2007, and was also prohibited from use in consumer products in Europe.16 Davies et al2 found that isopropyl nitrite has largely replaced isobutyl nitrite in poppers found at United Kingdom music festivals and nightclubs since the change in legislation. Cases 1 and 2 were ‘long-term’ users who only developed symptoms after this change. Cases of ‘poppers maculopathy’ may have been missed by ophthalmologists because of failure to enquire about recreational substance abuse, and specifically about poppers inhalation, as occurred in cases 1 and 2. Furthermore, SD-OCT imaging now allows this macular disturbance to be visualised. It is possible that any link of this previously unknown maculopathy to poppers inhalation is simply a chance occurrence. However, we see some evidence of causal link when reviewed against criteria for causality as derived from Sir Austin Bradford Hill17 and subsequently modified by Susser.18

The mechanism by which poppers may lead to macula toxicity, more specifically toxicity to subfoveal cones, is unclear. It is known that the volatile nitrites undergo rapid systemic clearance,19 however, they can lead to increases in NO synthase expression,20 and therefore prolonged NO production. NO has multiple interactions with photoreceptor physiology.21 However, there is little understanding of why isopropyl nitrite should be more toxic to the retina than isobutyl nitrite.

In our opinion, ophthalmologists encountering patients with unexplained foveal yellow spots and/or outer lamellar macular changes should ask about inhalation of poppers. The primary differential diagnosis includes inter alia photic maculopathy and adult onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy.22, 23

We have highlighted this message to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, to the Lesbian and Gay Foundation, and to the UK Home Office Advisory Council for the Misuse of Drugs. Surveillance for this matter in the United Kingdom may now be of merit. With mounting evidence, there may be a role for change in legislation to prohibit supply of isopropyl nitrite to the general public. Special regulatory controls exist where authorities have power to ban or control certain named products. However, the manufacturers often respond to such legal change by developing other unnamed compounds, as has appeared to have already happened with volatile nitrite compounds.2 Legislation change has been adopted in Austria in 2011 with respect to prohibiting all and unspecified products being marketed with the aim of being used by people to achieve a psychoactive effect.24 In conclusion, the potential for harm associated with use of poppers needs to be reassessed and public awareness raised.

References

Sigell LT, Kapp FT, Fusaro GA, Nelson ED, Falck RS . Popping and snorting volatile nitrites: a current fad for getting high. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135: 1216–1218.

Davies S, Salina J, Ramsey J, Holt D . Analysis of the Volatile Alkyl Nitrites. (Internet); 2010 (cited 12 January 2012). Available from: http://www.ltg.uk.net/admin/files/AlkylNitrites_FINAL.pdf.

Smith K, Flatley J . Drug Misuse Declared: Findings from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey. UK Home Office: London, 2011.

Ashworth S, Fountain J . Part of the Picture—The National LGB Drug & Alcohol Database. The Lesbian & Gay Foundation: Manchester, UK, 2011.

Winstock A . MixMag Drugs Survey: Mixmag. Development Hell Ltd.: London, 2011 pp 44–53.

Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C . Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet 2007; 369: 1047–1053.

Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, Paques M . Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1583–1585.

Audo I, El Sanharawi M, Vignal-Clermont C, Villa A, Morin A, Conrath J et al. Foveal damage in habitual poppers users. Arch Ophthalmol 2011; 129: 703–708.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). (Internet; cited 10 January 2012). Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk.

Edwards IR, Biriell C . Harmonisation in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 1994; 10: 93–102.

Fledelius HC . Irreversible blindness after amyl nitrite inhalation. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1999; 77: 719–721.

Pece A, Patelli F, Milani P, Pierro L . Transient visual loss after amyl Isobutyl nitrite abuse. Semin Ophthalmol 2004; 19: 105–106.

Davies AJ, Bhatt PB, Kelly SP . ‘Poppers Maculopathy’—An emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye 2012; 26: 888.

Lockwood B . Poppers: volatile nitrite inhalants. Pharmacy J 1996; 257: 154–155.

The Stationary Office. The Dangerous Substances and Preparations (Safety) Regulations 2006. The Stationary Office: London, 2006.

The Rapid Alert System for Non-Food Products (RAPEX)—EU Directive 76/769/EEC. (Internet); 2008 (cited 12 January 2012). Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/dyna/rapex/create_rapex.cfm?rx_id=217.

Hill AB . The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58: 295–300.

Susser M . What is a cause and how do we know one? A grammar for pragmatic epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 133: 635–648.

Kielbasa W, Fung HL . Pharmacokinetics of a model organic nitrite inhalant and its alcohol metabolite in rats. Drug Metab Dispos 2000; 28: 386–391.

Kielbasa W, Fung HL . Nitrite inhalation in rats elevates tissue NOS III expression and alters tyrosine nitration and phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 275: 335–342.

Goldstein IM, Ostwald P, Roth S . Nitric oxide: a review of its role in retinal function and disease. Vision Res 1996; 36 (18): 2979–2994.

Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Leroy BP, Hoyng CB, Keunen JE, den Hollander AI . The spectrum of ocular phenotypes caused by mutations in the BEST1 gene. Prog Retin Eye Res 2009; 28: 187–205.

Comander J, Gardiner M, Loewenstein J . High-resolution optical coherence tomography findings in solar maculopathy and the differential diagnosis of outer retinal holes. Am J Ophthalmol 2011; 152: 413–419 e6.

New Psychoactive Substances Law (Neue-Psychoaktive-Substanzen-Gesetz). BGBI. I Nr. 146/2011, December 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/tris/pisa/app/search/index.cfm?fuseaction=pisa_notif_overview&iYear=2011&inum=556&lang=EN&sNLang=EN.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Stuart Wilson, Community Optometrist, for clinical data and referral. We are grateful to Mr Peter Bogaert and Dr Peter Feldschreiber for legal comments. We are grateful to Dr John Ramsey, director of TICTAC, for advice.2

Ethical matters

Patient consent for publication was obtained.

Author contributions

AJD, SPK, and SGN are responsible for drafting this manuscript. AJD, SPK, PRB, and MMcK are responsible for conceiving this contribution. PRB, SPK, AJD, SGN, JS, JM, RH, and MMcK were involved in patient care. SPK and AJD are guarantors of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this subject matter.

Additional information

Some of this material was presented at the Yorkshire Retina Society meeting in 2011 and North of England Ophthalmic Society in March 2012.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, A., Kelly, S., Naylor, S. et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of ‘poppers maculopathy’. Eye 26, 1479–1486 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.191

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.191

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of the microvasculature in poppers maculopathy

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Beidseitiges Zentralskotom bei einem 28-jährigen Patienten mit CADASIL-Syndrom

Der Ophthalmologe (2016)

-

Is the mechanism of ‘poppers maculopathy’ photic injury?

Eye (2013)

-

Response to Fajgenbaum

Eye (2013)