Abstract

Purpose

To examine the evolution and complications of preretinal hemorrhage under silicone oil after diabetic vitrectomy.

Methods

A total of 44 cases of primary diabetic vitrectomy with silicone oil infusion were reviewed in a 3-year period. Intravitreal bevacizumab was used preoperatively for cases with active proliferation, and in all cases at the end of surgery. Intraoperative bleeding, postoperative extent of preretinal hemorrhage, blood reabsorption time, and reproliferation and treatment results were assessed.

Results

Maximal blood distributed in thin and scattered patterns (23 cases), thick and localized patterns (10 cases), or thick and scattered patterns (10 cases) developed within 1 week after surgery, and was largely reabsorbed within a month with improved postoperative vision. Confluent blood extending to the midperiphery (one case) resulted in severe fibrosis and detachment. Complications included fibrotic plaque (two cases), and fibrous band and thick membrane (seven cases). Six cases underwent preretinal tissue removal. Vision improvement≥3 lines was noted in three cases.

Conclusion

Most of the rebleeding occurred within the first post-op week, with gradual reabsorption in the posterior pole within 4 weeks; widespread confluent bleeding might result in severe reproliferation and detachment. A major complication of preretinal bleeding was the formation of preretinal fibrosis. Re-operation achieved a mild VA improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Treatment of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) with broad vitreoretinal adhesion causing severe retinal detachment may require the use of silicone oil for long-term retinal tamponade.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Preretinal blood under oil is a common occurrence after surgery, resulting from retained blood at the end of the surgery or from postoperative recurrent bleeding. Because blood and the factors containing within it have been shown to be potent stimuli for cellular proliferation7, 8 and silicone oil may sequester these proliferation-stimulating factors in the space between the retina and the oil, the presence of blood may become an important factor for peri-silicone oil proliferation, which is a major cause of surgical failure.9, 10, 11 Our previous study found that around 20% of cases with or without bevacizumab pretreatment had detectable recurrent hemorrhage under oil.1 Although anatomical and functional outcomes after primary diabetic vitrectomy with silicone oil infusion have been reported, how the preretinal blood under oil evolves and how the amount of blood influences structural changes have not been specifically studied. In addition, the surgical results for complications related to preretinal bleeding have not been evaluated. To better understand the influence of preretinal bleeding on visual prognosis, we undertook a retrospective study to examine the patterns of preretinal hemorrhage, its recurrence, reabsorption, and complications, as well as treatment results of complications.

Patients and methods

From 2006 to 2008, clinical charts of all patients who underwent vitrectomy with primary silicone oil infusion for severe diabetic retinopathy were reviewed. Patients who failed to gain retinal attachment at the end of surgery were excluded from the study. Patients with blood diseases or history of preoperative (within 2 weeks before surgery) or postoperative anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy (including heparin, warfarin and its derivatives, aspirin, or clopidogrel) were also excluded. The decision for silicone oil infusion was made during the operation. The criteria for oil infusion were: (1) four quadrants of severe proliferation with fibrovascular tissue extending beyond the equator in at least three quadrants and (2) the presence of residual traction or multiple breaks in different quadrants with suspected missed breaks after membrane dissection. In these conditions, we believed that the possibility of redetachment was high without long-term tamponade. All patients were followed up for at least 12 months after surgery. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before surgery. The same surgeon (C-MY) performed all operations.

Operative techniques

Intravitreal bevacizumab (1.25 mg) was used <1 week before surgery for active cases (defined as the presence of visible large new vessels within the proliferative tissue with fresh preretinal and/or vitreous hemorrhage). The basic surgical techniques are described elsewhere.12, 13 In brief, a 20-gauge vitrectomy system was set up in every case. Anterior–posterior traction release was attempted first, followed by fibrovascular tissue removal with delamination as the principal technique. Hemostasis was achieved by raising the infusion bottle, applying mechanical compression with a soft-tipped cannula, endodiathermy, or a combination of the above techniques. Blood clots were removed carefully, except those close to the bleeding sites, which were trimmed to small islands. Fluid–air exchange with internal drainage of subretinal fluid was performed through pre-existing or iatrogenic breaks followed by supplementary panretinal photocoagulation extending beyond the equator, peripheral cryotherapy, and silicone oil (5000 cs) infusion. In certain cases, a 360° encircling buckle was placed to counter possible residual peripheral vitreous traction. Bevacizumab (0.05 mg) in an insulin syringe was injected through an upper sclerotomy just before silicone oil infusion in every case.

After surgery, patients were kept in a prone position overnight and were allowed to lie on either side during sleep thereafter, but maintained a head-down position during waking hours for 2 weeks. Ophthalmological examinations were performed daily for the first 1 week after surgery, then weekly for 4 weeks, biweekly for 1 month, and monthly for at least 6 months. The demographics and clinical findings collected included age, sex, study eye, type and duration of diabetes mellitus, systemic diseases such as hypertension, renal insufficiency, best-corrected visual acuity, intraocular pressure, intraoperative findings, degree of intraoperative bleeding, surgery duration, combined lens extraction, and the use of a scleral buckle. The extent of neovascularization, the severity of retinal traction, and the amount of fresh vitreous hemorrhage before surgery were documented. Data regarding the extent, severity change, and distribution pattern of preretinal blood in the postoperative period, time, duration, and frequency of recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, and duration of follow-up were also compiled.

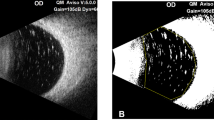

Intraoperative bleeding was classified into three grades: grade 1, minor bleeding that stopped either spontaneously or by transient bottle elevation; grade 2, moderate bleeding requiring endodiathermy or with the formation of broad sheets of clots extending away from the bleeding site; and grade 3, thick clot formation covering at least half of the posterior pole or interfering with the surgical plane.14 Postoperative preretinal blood was classified into four grades according to blood thickness and distribution: grade 1, localized or scattered thin layers of clot distributed over one to four quadrants; grade 2, localized thick layers of clot distributed over one or two quadrants; grade 3, scattered thick layers of clot distributed over more than two quadrants; and grade 4, confluent thick layers of hemorrhage involving the whole posterior pole and four quadrants (Figures 1a–d). Any noticeable increase in preretinal blood was defined as recurrent hemorrhage. The thickness of the blood clot was judged from its color: dark red indicated a thick layer of clot; bright red indicated a thin layer of clot. Maximal amount of preretinal blood was used for grading the extent of hemorrhage. The severity of intraoperative bleeding in each case was graded and agreed upon by two investigators performing the operations together in our group (Yeh and Yang), as was the severity and distribution patterns of postoperative preretinal hemorrhage (by Yang and Yang). Fundus pictures were taken on the first postoperative day and after rebleeding to the maximal size. Indirect ophthalmoscopy and fundus photography were used to determine the location, size, and pattern of the preretinal blood. Upon disagreement between examiners or in indeterminate cases, measurement of the hemorrhage area on the fundus pictures was performed using the individual disc size as the measuring unit. The severity of intraoperative bleeding, the extent of postoperative preretinal bleeding, blood reabsorption time within the posterior pole and around the disc area, the rate of recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, and the change of best-corrected visual acuity were documented. All visual acuity results were converted to logMAR for statistical analysis. Complications related to preretinal blood were recorded. The classification and data collection were possible because it had been our practice to carefully document the changes by two independent examiners for every diabetic case that had undergone vitrectomy. Posterior preretinal fibrosis formed where previous preretinal blood had been present or had occurred in the adjacent area, and was considered to be a complication of the preretinal blood. Selected cases with such condition underwent further surgery. The indication for operation was macular structural changes by fibrotic re-proliferation with decreased visual acuity, but without extensive retinal atrophy or disc pallor.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean±SD. Paired t-test was performed in comparing pre- and postoperative logMAR visual acuity. Statistical analyses of non-continuous variables were performed with χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A multiple lineal regression analysis was performed to determine the significance of the following factors related to the intra-operative hemorrhage: age, sex, active or fibrotic type of PDR, duration of diabetes (<10 years or ≥10 years), hypertension, and renal insufficiency. Pre-operative bevacizumab and scleral buckle were also added into another regression model for analyzing the associated factors of postoperative hemorrhage. All of the statistical analyses were performed using STATA 8.2 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

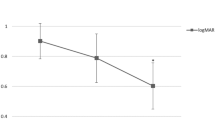

A total of 44 cases (44 eyes in 44 patients) were collected, with a male–female ratio of 20 : 24 and an average age of 51.0±8.7 years. Of these, 29 cases were predominantly active and had received bevacizumab injection within 1 week before surgery, while 15 cases had basically fibrotic tissue proliferation. All cases had either mild (25 cases) or moderate (19 cases) intraoperative bleeding. Twelve cases (27.3%) had recurrent hemorrhage. Ten cases had a single episode of recurrent hemorrhage and two cases had a second episode of rebleeding. All recurrent hemorrhages occurred within the first week after surgery. There was no statistical difference between active and inactive cases in recurrent hemorrhage (P=0.50). Blood reabsorption time (posterior pole and around the disc) was 3.6±1.7 weeks on average. Pre-operative best-corrected visual acuity ranged from light perception to 20/200 (average 1.78±0.21 in LogMAR vision); postoperative best-corrected visual acuity at the end of follow-up ranged from light perception to 20/50 (average 1.51±0.41 in LogMAR vision). The difference was statistically significant (P=0.0002).

Grade 1 severity of postoperative preretinal hemorrhage was found in 14 cases (48.3%) in the active proliferation group and in 9 cases (60.0%) in the predominantly fibrotic group; grade 2 to 4 hemorrhage was found in 6, 8, 1 cases in the active group and 4, 2, 0 cases in the fibrotic group. The proportion of grade 2 or more severe hemorrhage was 15/29 cases (51.7%) and 6/15 cases (40.0%) in the two groups (P=0.89).

Clinical observations showed that a scattered thin pattern had complete resolution (Figure 2); grade 2 and 3 postoperative hemorrhage also showed gradual resolution (Figure 3). However, some grade 2 (3/10) and grade 3 (6/10) preretinal blood may result in preretinal fibrotic bands (3 cases), thick fibrotic membrane (4 cases) or plaque (2 cases) (Figure 4); the only case of grade 4 resulted in a thick and confluent pattern and ended up with retinal detachment.

An example of resolution of grade 1 (scattered thin pattern) preretinal blood. (a) The preoperative fundus picture shows severe fibrovascular proliferation with traction detachment in a 46-year-old woman. (b). Maximum bleeding of grade 1 severity developed 1 week after the surgery. (c) Resolution of hemorrhage in the posterior pole was noted 6 weeks after the surgery.

An example of resolution of grade 3 (scattered thick pattern distributed over more than two quadrants) preretinal blood. (a) The preoperative fundus picture shows severe fibrovascular proliferation with traction detachment in a 34-year-old man. (b) Maximum bleeding of grade 3 severity developed 1 week after the surgery. (c) Resolution of hemorrhage in the posterior pole was noted 6 weeks after surgery.

Preretinal fibrosis after resolution of preretinal blood. (a) Grade 2 preretinal hemorrhage developed after surgery of severe fibrovascular proliferation with traction detachment in a 59-year-old man. (b) Preretinal fibrotic band gradually developed 3 months after the surgery. (c) The preoperative fundus picture shows severe fibrovascular proliferation with traction detachment in a 42-year-old man. (d) After resolution of grade 3 preretinal blood postoperatively, preretinal fibrotic plaque gradually developed 3 months after the surgery.

The multiple linear regression analysis model revealed that the grade of intraoperative bleeding was only significantly associated with the active type of PDR (P=0.04), but no factors could be identified to be associated with the grade of postoperative bleeding.

Six of nine patients underwent further membrane removal surgery in an average of 5.2±2.1 months after primary operation. During the operation, proliferative tissues that adhered to major vessels were noted in four cases. Silicone oil was removed in all cases. Anatomic improvement was noted in 5/6; best-corrected visual acuity improved in five of the six cases, and in three of them for more than three lines (Table 1). No case had recurrent retinal detachment or other complications, such as abnormal intraocular pressure. However, significant recurrent membrane was noted in three cases within postoperative 3 months. An example is shown in Figure 5.

Treatment of preretinal fibrosis developed after resolution of preretinal blood. (a) The preoperative fundus picture shows severe fibrovascular proliferation with traction detachment in a 31-year-old woman. (b) After resolution of grade 2 preretinal blood postoperatively, preretinal fibrotic band causing macular dragging gradually developed 3 months after the surgery. (c) Removal of preretinal tissue resulted in normal appearance of the macula. (d) Recurrence of a preretinal membrane of less severity developed 3 months after the second operation.

Discussion

In a silicone oil-infused eye, blood is confined to a limited preretinal space between the retina and the oil. Various cytokines or growth factors derived from the ischemic retina or contained within the blood clots are highly concentrated, greatly enhancing tissue reproliferation.10, 11 On the other hand, the mechanical effect and the compartmentalization of various factors, including anti-coagulant factors, provided by the oil may possibly have the effect of limiting the frequency or severity of recurrent hemorrhage.15 In this study, we followed and recorded the evolution of preretinal blood under oil after diabetic vitrectomy to examine its reabsorption pattern and complications. Unlike the conventional concept which holds that preretinal blood almost always induces a thick fibrotic membrane and greatly disturbs vision,16, 17 our study showed that most preretinal blood would be gradually reabsorbed. We separated preretinal blood into several categories depending on the involved area, distribution patterns, and thickness. Only one case with massive preretinal blood covering the whole posterior pole and extending to the periphery failed to be reabsorbed and resulted in reproliferation with retinal detachment. Significant localized reproliferation was found with increasing rate in grade 2 and 3 preretinal hemorrhage (3/10 and 6/10, respectively). Others might have thin epiretinal membrane (ERM) formation without obvious macular structural changes. These results suggest in the majority of cases that silicone oil may be safely used as the substance for long-term tamponade in primary complicated vitrectomy.

Amounts of blood clots during surgery may directly influence the severity of preretinal blood after surgery. Apart from careful intraoperative manipulations, methods have been developed to decrease the intraoperative bleeding during surgery. Presurgical bevacizumab has been shown to decrease intraoperative bleeding in cases with active NV.1, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 In this study, all cases with active FVP received intravitreal bevacizumab 3–7 days before operation. In cases with predominantly fibrotic tissue, intravitreal bevacizumab may cause more traction without the benefit of reducing the likelihood of intraoperative bleeding.23 Some investigators have suggested the use of bevacizumab at the end of operation to reduce postoperative hemorrhage induced by early growth of neovascularization.24, 25 We injected 0.05 mg of bevasizumab before silicone oil infusion in an attempt to inhibit early postoperative neovascularization. The exact effect of the treatment in a silicone oil-filled eye remains to be studied.

Recurrent hemorrhage under oil manifests itself as fresh preretinal hemorrhagic patches, or as an increase in size and darkening in color of pre-existing hemorrhagic patches. It usually occurs within 1 week after surgery. In this study, more than one-fourth of the cases had recurrent bleeding. Thus, silicone oil cannot completely prevent recurrent hemorrhage; however, it does have the effect of confining recurrent hemorrhage. In our study, recurrent hemorrhage rarely becomes too massive to involve the whole posterior retina and extending into the periphery. Only one case had massive postoperative preretinal hemorrhage. None of our other cases with recurrent hemorrhage ended up with severe reproliferation. These results seem to suggest that patients may be safely followed for spontaneous reabsorption of preretinal blood even if scattered thick layers of clot distributed over more than two quadrants have been observed postoperatively. However, massive confluent hemorrhage involving the posterior pole and four quadrants of the retina may be associated with severe reproliferation and detachment. In such conditions, perhaps early oil removal should be considered.

Although in most cases spontaneous blood reabsorption is anticipated, the area where blood clots were located or were nearby may form the preretinal membrane during follow-up. We believe that these membranes may be either directly transformed from the blood clots or were significantly contributed by the presence of blood clots. The formation of ERM under oil is common after vitreoretinal surgery even without the presence of blood. In this study, we found that important features of ERM under oil associated with blood clot are the propensity of the formation of fibrotic bands and its attachment of the membrane with normal blood vessels. Attempting to remove the tissue with forceps pulling was likely to cause bleeding and render adequate removal of the membrane difficult. Proper ERM removal may result in gradual normalization of the macular structure. However, we found that significant recurrent membrane was noted in half of the operated cases in <3 months, suggesting the persistent, strong, pro-proliferative microenvironment of these eyes.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature; however, study bias was kept as low as possible by our careful documentation of the clinical data and our employment of two investigators to evaluate clinical changes. Our study showed that rebleeding under oil after diabetic vitrectomy was not rare; recurrent hemorrhages usually occurred within the first post-op week; except confluent extensive rebleeding, blood clots in the posterior pole were reabsorbed in most cases within 4 weeks; widespread confluent blood carries poor prognosis. Major complications of preretinal blood were the formation of preretinal fibrotic bands or fibrotic plaques. Re-operation achieved only mild VA improvement. Recurrent ERM was frequent. A large-scale prospective study may be necessary to confirm our observations.

References

Yeh PT, Yang CM, Lin YC, Chen MS, Yang CH . Bevacizumab pretreatment in vitrectomy with silicone oil for severe diabetic retinopathy. Retina 2009; 29 (6): 768–774.

Castellarin A, Grigorian R, Bhagat N, Del Priore L, Zarbin MA . Vitrectomy with silicone oil infusion in severe diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87 (3): 318–321.

Douglas MJ, Scott IU, Flynn Jr HW . Pars plana lensectomy, pars plana vitrectomy, and silicone oil tamponade as initial management of cataract and combined traction/rhegmatogenous retinal detachment involving the macula associated with severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2003; 34 (4): 270–278.

Hoerauf H, Roider J, Bopp S, Lucke K, Laqua H . Endotamponade with silicon oil in severe proliferative retinopathy with attached retina. Ophthalmologe 1995; 92 (5): 657–662.

McLeod D . Silicone oil in diabetic vitrectomy. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87 (10): 1303–1304; author reply 1304-1306.

Shen YD, Yang CM . Extended silicone oil tamponade in primary vitrectomy for complex retinal detachment in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A long-term follow-up study. Eur J Ophthalmol 2007; 17 (6): 954–960.

Burke JM, Smith JM . Retinal proliferation in response to vitreous hemoglobin or iron. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981; 20 (5): 582–592.

Pinon RM, Pastor JC, Saornil MA, Goldaracena MB, Layana AG, Gayoso MJ et al. Intravitreal and subretinal proliferation induced by platelet-rich plasma injection in rabbits. Curr Eye Res 1992; 11 (11): 1047–1055.

Oyakawa RT, Schachat AP, Michels RG, Rice TA . Complications of vitreous surgery for diabetic retinopathy. I. Intraoperative complications. Ophthalmology 1983; 90 (5): 517–521.

Asaria RH, Kon CH, Bunce C, Sethi CS, Limb GA, Khaw PT et al. Silicone oil concentrates fibrogenic growth factors in the retro-oil fluid. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88 (11): 1439–1442.

Lewis H, Burke JM, Abrams GW, Aaberg TM . Perisilicone proliferation after vitrectomy for proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology 1988; 95 (5): 583–591.

Yeh PT, Yang CM, Yang CH, Huang JS . Cryotherapy of the anterior retina and sclerotomy sites in diabetic vitrectomy to prevent recurrent vitreous hemorrhage: an ultrasound biomicroscopy study. Ophthalmology 2005; 112 (12): 2095–2102.

Yang CM, Yeh PT, Yang CH . Intravitreal long-acting gas in the prevention of early postoperative vitreous hemorrhage in diabetic vitrectomy. Ophthalmology 2007; 114 (4): 710–715.

Yang CM, Yeh PT, Yang CH, Chen MS . Bevacizumab pretreatment and long-acting gas infusion on vitreous clear-up after diabetic vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 146 (2): 211–217.

Charles S, Katz A, Wood B (eds). Vitreous Microsurgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philaldelphia, 2002, pp 104–125.

Kono T, Kohno T, Inomata H . Epiretinal membrane formation. Light and electron microscopic study in an experimental rabbit model. Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113 (3): 359–363.

Bringmann A, Wiedemann P . Involvement of Muller glial cells in epiretinal membrane formation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 247 (7): 865–883.

Ishikawa K, Honda S, Tsukahara Y, Negi A . Preferable use of intravitreal bevacizumab as a pretreatment of vitrectomy for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eye (Lond) 2009; 23 (1): 108–111.

Yamaji H, Shiraga F, Shiragami C, Nomoto H, Fujita T, Fukuda K . Reduction in dose of intravitreous bevacizumab before vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2011; 129 (1): 106–107.

Abdelhakim MA, Macky TA, Mansour KA, Mortada HA . Bevacizumab (Avastin) as an adjunct to vitrectomy in the management of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a prospective case series. Ophthalmic Res 2011; 45 (1): 23–30.

Hernandez-Da Mota SE, Nunez-Solorio SM . Experience with intravitreal bevacizumab as a preoperative adjunct in 23-G vitrectomy for advanced proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2010; 20 (6): 1047–1052.

Modarres M, Nazari H, Falavarjani KG, Naseripour M, Hashemi M, Parvaresh MM . Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab before vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol 2009; 19 (5): 848–852.

Arevalo JF, Maia M, Flynn Jr HW, Saravia M, Avery RL, Wu L et al. Tractional retinal detachment following intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in patients with severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92 (2): 213–216.

Park DH, Shin JP, Kim SY . Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and triamcinolone acetonide at the end of vitrectomy for diabetic vitreous hemorrhage: a comparative study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010; 248 (5): 641–650.

Cheema RA, Mushtaq J, Al-Khars W, Al-Askar E, Cheema MA . Role of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injected at the end of diabetic vitrectomy in preventing postoperative recurrent vitreous hemorrhage. Retina 2010; 30 (10): 1646–1650.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

The work has not been presented at any meeting before.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yeh, PT., Yang, CM. & Yang, CH. Distribution, reabsorption, and complications of preretinal blood under silicone oil after vitrectomy for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eye 26, 601–608 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.318

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.318

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Refining vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Silicone oil removal after extended tamponade in proliferative diabetic retinopathy—a long range of follow-up

Eye (2020)

-

Safety and efficacy of transpupillary silicone oil removal in combination with micro-incision phacoemulsification cataract surgery: comparison with 23-gauge approach

BMC Ophthalmology (2018)

-

Surgical Management of Tractional Retinal Detachments in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

Current Ophthalmology Reports (2016)

-

Clinical and histological features of epiretinal membrane after diabetic vitrectomy

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2014)