Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its risk factors among patients undergoing cataract surgery.

Methods

A retrospective observational case–control study of all the members older than 50 years who underwent cataract surgery in the Central District of Clalit Health Services in Israel (years 2000–2007) (n=12 984) and 25 968 age- and gender-matched controls. We calculated the prevalence of CVDs’ and their risk factors, including carotid artery disease (CAD), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), systemic arterial hypertension (HTN), chronic renal failure (CRF), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), congestive heart failure, diabetes, smoking, alcohol abuse, and hyperlipidaemia. The main outcome measures were the odds ratio of having CVDs among cataract patients undergoing surgery compared with controls.

Results

No difference was found in demographics (age, gender, marriage status, socioeconomic class, and living place) between the study and control groups. All CVDs’ risk factors were significantly more prevalent in cataract patients in univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association of the following with cataractogenesis: diabetes, CAD, HTN, PVD, smoking, IHD, CRF, hyperlipidaemia, and Ashkenazi origin.

Conclusions

CVDs and their risk factors are more prevalent among cataract patients undergoing cataract surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is generally acknowledged that age-related (senile) cataract is a multifactorial disease. Epidemiologic studies of this disease have suggested many risk factors for cataract.1 Diabetes, glaucoma, several analgesics, myopia, renal failure, smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, hypertension (HTN), low body mass index, use of cheaper cooking fuel, working in direct sunlight, family history of cataract, occupational exposure, and several biochemical factors are just a partial list of the potential risk factors for cataract.2 Interactions among the risk factors can mask the real contribution of each in the development of the diseases. An intriguing link between development of age-related cataracts and increased future risk of coronary heart disease has been suggested.3

As free radical-mediated oxidative damage to lipoproteins may accelerate atherosclerosis as well as cataract formation,4 the development of cataract might be a marker for such damage and, therefore, might be associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease.3

Although some studies support the association of cataract and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs),5 other studies reporting cataract risk factors do not mention CVD. Klein et al6 in the Beaver Dam Eye study reported that CVDs and their risk factors have little effect on the incidence of age-related cataract.

This study aims to evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular morbidity among 12 984 cataract patients undergoing cataract surgery in Israel.

Materials and methods

Study population

The electronic medical records of all members who underwent cataract surgery in the ‘Central District’ of the ‘Clalit Health Services’ health maintenance organization (HMO) in Israel, aged 50 years and older on 1 January 2000, and who did not terminate their membership until 31 December 2007, were included (n=12 984); cataract patients that died or left the HMO during the study period (n=2251) were excluded.

For each cataract patient in the study group, two members of the HMO that were matched in age and gender and did not undergo cataract surgery (n=25 968) were randomly selected from all the members of the HMO (aged 50 years and older) that were members of the HMO on 1 January 2000 and did not discontinue membership (for any reason, including death) till 31 December 2007.

The study was approved by the institutional review board. Informed consent was not required.

Observation procedures

The ‘Clalit Health Services’ HMO maintains a chronic disease registry database, which includes information collected from a variety of sources: primary care physician reports, medication-use files, hospitalization records, and out-patient clinic records. The methods of registry acquisition and maintenance were described elsewhere.7

We extracted information from the registry regarding all participants in the study, looking for the following CVD or CV risk factors: carotid artery disease (CAD), diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), systemic arterial HTN, chronic renal failure (CRF), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), congestive heart failure (CHF), smoking, alcohol abuse, and hyperlipidaemia. The HMO's definitions of HTN are according to the reports of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure.8 Definitions of hyperlipidaemia are based on the European SCORE project.9 Definitions of diabetes are based on the WHO classification.10 CAD was defined by the colour flow duplex ultrasound scan and the typical clinical findings.11 PVD was classified by the Fontaine stages.12 Chronic kidney disease was identified by a blood test for creatinine,13 together with the clinical diagnosis of the treating physicians.

Additional information extracted from patients’ files included age, gender, region of birth (Ashkenazi origin—people born in Europe, North and South America, and Australia vs Sephardic origin those born in Asia and Africa (mainly in the Middle East and North Africa)), place of residency (living in urban (>10 000 inhabitants) or rural (<10 000 inhabitants), marriage status, and social security economic status (indicating members that are exempt from paying social security tax because of a low-socioeconomic status).

Outcome measures

The odds ratio (OR) of having CVDs among cataract patients undergoing surgery compared with controls.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used for continuous variables and χ2 test with Yates’ correction for proportions (SPSS ver.12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)). Probabilities of <5% were considered statistically significant. A logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for the simultaneous effects of the various CVD and CV risk factors as well as age, gender, marriage status, country of birth, place of residency, and socioeconomic status on undergoing cataract surgery.

Results

A total of 12 984 patients underwent cataract surgery during the study period. We examined various CVD and CV risk factors for those patients and compared them with an age- and gender-matched control group from the population of the district (n=25 968). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study populations. No difference was found in demographics (age, gender, marriage status, socioeconomic class, and living place) between the study and control groups except for the patient's origin. The percentage of the Ashkenazi origin patients was significantly lower in the cataract surgery patients than in the matched controls (P<0.0001).

Univariate analyses

Table 2 shows the prevalence of various CVDs and CV risk factors among patients undergoing cataract surgery vs matched controls.

All CVDs and their risk factors were significantly more prevalent among cataract surgery patients. The OR was highest for CAD (OR=1.51), followed by diabetes (OR=1.50), PVD (OR=1.42), and HTN (OR=1.35). P-value was <0.0001 for all the risk factors except for alcohol abuse (P=0.02). Figure 1 shows the proportion of patient with CAD, diabetes, CHF, and HTN among cataract patients and matched controls stratified by age. As can be seen, in most age groups, the difference between cataract patients and controls was highly significant.

Table 3 compares the ORs for various CVDs in patients undergoing cataract surgery and in matched controls in males and females. No significant differences were seen between the genders regarding the association of various CVDs and CV risk factors with cataract surgery.

As the cases and controls differed in their region of origin (Ashkenazi vs Sepharadi), we compared the ORs for various CVDs in Ashkenazi patients separately (Table 4). The association between CVDs and cataract remained statistically significant for all CVDs and CV risk factors except for alcohol abuse.

Multivariate analysis

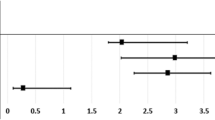

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed a significant effect of nine variables on the ORs for undergoing cataract surgery: diabetes (OR=1.35, P<0.001), CAD (OR=1.27, P<0.001), HTN (OR=1.20, P<0.001), smoking (OR=1.18, P<0.001), IHD (OR=1.14, P<0.001), CRF (OR=1.12, P=0.002), PVD (OR=1.12, P=0.002), hyperlipidaemia (OR=1.08, P=0.002), and Ashkenazi origin (OR=0.83, P<0.001) (Figure 1). However, two variables, which were included in the univariate analyses, were no more significant (CHF (OR=1.03, P=0.55) and alcohol abuse (OR=1.22, P=0.24)).

Discussion

This study shows that various CVDs and CV risk factors have a significantly higher OR in cataract patients undergoing surgery. Epidemiologic data on cataract and the risk of CVDs were examined in earlier studies.5 Although CVDs were not significantly related to cataract in multivariate analysis in the Melbourne VIP study,14 a significant positive association between cataract extraction and CVDs was shown in other studies. Hu et al3 in a prospective study on women nurses found a significant positive association between cataract extraction and the incidence and the overall mortality from coronary heart disease (RR=1.88 and 1.37, respectively). A recent prospective cohort study of Swedish women has also shown that metabolic syndrome and its components (abdominal adiposity, diabetes, and HTN) is associated with the risk of cataract development.15 Another prospective study of male physicians with self-reported cataract reported a relative risk of 1.34 (CI=0.78, 2.32) for fatal cardiovascular events during 5 years of follow-up.16 As the above studies have shown the association of cataract and CVDs separately in males and females, this study shows comparable results for men and women (Table 3).

Interestingly, we found that, for both males and females, the CVD most significantly associated with cataract was CAD. As the carotid is the blood supplier to the eye, CAD can cause cataract by reducing ocular circulation.17 It has been shown that reduced ocular blood flow is partly responsible for various eye diseases.18 Similarly, a high mean velocity in the ophthalmic artery may be associated with a reduced risk of cataract.17

The significant association that we found of both diabetes and smoking with cataract formation was consistently reported across multiple studies.19 Smoking has been found to be associated with both nuclear and PSC cataract,20 and the degree of opacification was shown to be correlated to the dose and pack-years of use.19 Smoking cessation was shown to reduce damage, suggesting a reversible component.16

Similarly, several population-based prospective studies have reported that diabetes is a risk factor for both cortical and PSC cataract.21 A reduced effect of diabetes on cataractogenesis in people over 60 years22 was reported and could be attributed to the increasing influence of other factors washing out the effect of diabetes.19 We also noted a reduction in the effect of diabetes on cataractogenesis with age (Figure 1b), although some effect was present even in patients in their eighties (P<0.001).

Oxidative damage is hypothesized to be the mechanism through which diabetes and smoking may induce cataract.19 The ocular lens, which is exposed to light and ambient oxygen, is particularly sensitive to photooxidative damage.4 Indeed, high levels of many antioxidants exist naturally in the various structures of the eye,23 and extensive oxidation of proteins and other components of the lens have been observed in human cataracts.3

It has been hypothesized that cataract formation reflects more generalized tissue damage associated with oxidative stress, which has been characterized as part of the ageing process,24 The positive association between cataract extraction and incident CVD observed in our study lends indirect support to the function that oxidative stress may have in the pathogenesis of both CVD and cataract.

Another potential mechanism for a positive association between cataract and CVDs may be the glycosylation of tissue proteins associated with diabetes.25 Even among nondiabetics, glycosylation of protein resulting from glucose intolerance may partly contribute to the association between cataract and CVD.3

New evidence suggests that an inflammatory process may also have a function, because elevated serum levels of CRP and interleukin-6 have been associated with diabetes26 and cataractogenesis.

Elevated serum lipids have long been well associated with CVDs.27 The contribution of fatty acids metabolism and serum lipids to cataractogenesis seems to be more complex.27 As some fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid are protective against cataract, some other fatty acids such as linoleic and linolenic acid were associated with higher risk of nuclear cataract.28 Animal studies indicate that these factors interact to promote cataract development, and modification of one factor may be used to reduce risk from another.29

Similar to our findings, HTN has also been associated with cataract in other cross-sectional30 and case–control studies. However, the results are inconsistent31 and the Blue Mountains Eye Study even reported HTN to be inversely related to nuclear cataract (OR=0.8).31 The mechanism relating HTN to cataract is unclear, but the association of HTN with elevated CRP levels might also indicate an underlying inflammatory process.15

Potential limitations of our study must also be considered. Although detailed information on a multitude of potential confounders was collected and adjusted for, the authors cannot rule out the possibility that unmeasured confounders may explain the observed association.3 Being retrospective, there are inherent limitations in the study. Our case–control study is based on the inherent assumption that patients who are not undergoing cataract surgery do not have cataract. It is possible that some patients had cataract, which had no clinical effect or which did not undergo operation as a result of other different reasons. This may be a potential confounder. However, as the study population is relatively homogeny demographically, we believe that the results were not influenced significantly.

We selected controls that did not have cataract surgery. We did not want to limit the controls to only those members that visited an eye clinic, as this might introduce other ocular pathologies in the control group and lead to various biases. However, although the accessibility to health services in Israel is quite high, we assume that if the control patients might have had a visual significant cataract, they would have seen an ophthalmologist and be referred for cataract surgery.

In the Israeli health care system, all patients in the study had the same access to cataract extraction.

However, we cannot exclude a possibility for potential bias because of the underestimation of cataract prevalence, which would lead to diluted risk estimates.15 As we used cataract surgery as a surrogate for cataract, it is possible that the more severely ill cardiovascular patients would not have undergone elective cataract surgery in spite of having cataract. This would act to diminish the association between cataract and CVDs. The fact that in spite of that we found significant associations means that the association of cataract with the various CVDs might be even stronger than reported here.

In conclusion, in a large cohort of 12 984 cataract patients undergoing cataract surgery and 25 968 controls, CVDs were significantly more prevalent among cataract patients. As so many epidemiologic risk factors for cataract have been identified, and currently, there are no tested strategies for the primary prevention of cataract in the community,32 the future of cataract research should focus on the primary prevention of cataract. It may be achieved by performing more complex study designs looking at multiple factors that contribute to a single mechanism of cataractogenesis.19 The need to standardize exposure and outcome measurements will become more important as clinicians seek to synthesize data better from multiple studies.

References

Hodge WG, Whitcher JP, Satariano W . Risk factors for age-related cataracts. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17: 336–346.

Ughade SN, Zodpey SP, Khanolkar VA . Risk factors for cataract: a case control study. Indian J Ophthalmol 1998; 46: 221–227.

Hu FB, Hankinson SE, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Speizer FE et al. Prospective study of cataract extraction and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 153: 875–881.

Varma SD . Scientific basis for medical therapy of cataracts by antioxidants. Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 53: 335S–345S.

Goodrich ME, Cumming RG, Mitchell P, Koutts J, Burnett L . Plasma fibrinogen and other cardiovascular disease risk factors and cataract. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1999; 6: 279–290.

Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE, DeMets DL . Relation of ocular and systemic factors to survival in diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 266–272.

Rennert G, Peterburg Y . Prevalence of selected chronic diseases in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J 2001; 3: 404–408.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–2572.

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP . Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 987–1003.

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ . Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 539–553.

Louridas G, Junaid A . Management of carotid artery stenosis. Update for family physicians. Can Fam Physician 2005; 51: 984–989.

Fontaine R, Kim M, Kieny R . [Surgical treatment of peripheral circulation disorders.]. Helv Chir Acta 1954; 21: 499–533.

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 2034–2047.

McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Fu CL, Taylor HR . The epidemiology of cataract in Australia. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 128: 446–465.

Lindblad BE, Håkansson N, Philipson B, Wolk A . Metabolic syndrome components in relation to risk of cataract extraction: a Prospective Cohort Study of Women. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1687–1692.

Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Seddon JM . Cataract and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease (Abstract). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33: 2026.

Patterson JW . Effect of blood supply on the development of cataracts. Am J Physiol 1955; 180: 495–497.

Barkana Y, Harris A, Hefez L, Zaritski M, Chen D, Avni I . Unrecordable pulsatile ocular blood flow may signify severe stenosis of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 1478–1480.

Abraham AG, Condon NG, West Gower E . The new epidemiology of cataract. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2006; 19: 415–425.

DeBlack SS . Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for cataract and age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Optometry 2003; 74: 99–110.

Hennis A, Wu SY, Nemesure B, Leske MC . Risk factors for incident cortical and posterior subcapsular lens opacities in the Barbados Eye Studies. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 525–530.

Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Connell AM, Hyman L, Schachat A . Diabetes, hypertension, and central obesity as cataract risk factors in a black population. The Barbados Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 35–41.

Trevithick JR, Mitton KP . Vitamin C and E in cataract risk reduction. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2000; 40: 59–69.

Stadtman ER . Protein oxidation and aging. Science 1992; 257: 1220–1224.

Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE . Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, selected cardiovascular disease risk factors, and the 5-year incidence of age-related cataract and progression of lens opacities: the Beaver Dam Eye study. Am J Ophthalmol 1998; 126: 782–790.

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Buring JE, Rifai N, Ridker PM. . C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2001; 286: 327–334.

Hiller R, Sperduto RD, Reed GF, D’Agostino RB, Wilson PW . Serum lipids and age-related lens opacities: a longitudinal investigation: the Framingham Studies. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 578–583.

Lu M, Cho E, Taylor A, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Jacques PF . Prospective study of dietary fat and risk of cataract extraction among US women. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161: 948–959.

Tsutsumi K, Inoue Y, Yoshida C . Acceleration of development of diabetic cataract by hyperlipidemia and low high-density lipoprotein in rats. Biol Pharm Bull 1999; 22: 37–41.

Tavani A, Negri E, La Vecchia C . Selected diseases and risk of cataracts in women: a case-control study from northern Italy. Ann Epidemiol 1995; 5: 234–238.

Schaumberg DA, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, Ajani UA, Stürmer T, Hennekens CH . A prospective study of blood pressure and risk of cataract in men. Ann Epidemiol 2001; 11: 104–110.

McCarty CA, Taylor HR . A review of the epidemiologic evidence linking ultraviolet radiation and cataracts. Dev Ophthalmol 2002; 35: 21–31.

Acknowledgements

The paper was presented in part as a poster during the AAO conference in Atlanta, November 2008. All authors have read and approved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Eye website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nemet, A., Vinker, S., Levartovsky, S. et al. Is cataract associated with cardiovascular morbidity?. Eye 24, 1352–1358 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.34

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.34

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Associations of hospitalisation – admission, readmission and length to stay – with multimorbidity patterns by age and sex in adults and older adults: the ELSI-Brazil study

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

-

Identifying temporal patterns in patient disease trajectories using dynamic time warping: A population-based study

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Latent class analysis of multimorbidity patterns and associated outcomes in Spanish older adults: a prospective cohort study

BMC Geriatrics (2017)

-

Does early onset cataract increase the risk of ischemic stroke? A nationwide retrospective cohort study

Internal and Emergency Medicine (2017)

-

The impact of preoperative evaluation on perioperative events in patients undergoing cataract surgery: a cohort study

Eye (2016)