Abstract

Purpose

To describe the outcomes of a simple technique of anterior lamellar excision (ALE) with laissez-faire healing for management of aberrant lashes in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP).

Methods

Prospective interventional case series.

Results

Seven OCP patients underwent grey line split and ALE with laissez-faire healing over a 24-month period in a tertiary referral centre. All patients had undergone previous interventions for the misdirected lashes. Nine procedures were undertaken (three upper and six lower lids). Mean follow-up was for 25.66±12.3 months (range: 9–43 months). Residual lashes were noted in three patients. In two cases, the lashes were isolated and managed successfully by a single electrolysis treatment. One patient needed further ALE for residual remnant of trichiatic cilia at the lateral edge of the lid. All patients were satisfied with their post-operative appearance. None of the patients showed exacerbation of disease or needed additional immunosuppression as a consequence of the lid surgery.

Conclusions

Anterior lamellar excision with spontaneous granulation is a simple and effective procedure for management of aberrant lashes. Risk of disease exacerbation was reduced in OCP with minimal conjunctival manipulation and reduced post-operative lash-globe touch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Management of aberrant lashes is particularly challenging in the presence of an underlying progressive cicatricial pathology (eg, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, OCP), which is occasionally undiagnosed before the intervention.1 An external approach to avoid conjunctival manipulation and proceeding after adequate immunosuppression or with quiescent disease has been advocated to prevent disease exacerbation.2, 3, 4 Excision of involved lash follicles can be a definite treatment and has previously been combined with advancement of the skin muscle layer.5, 6 We reported a modification with the excision of the lash-bearing anterior lamellar strip in a preliminary study of three cases of recurrent trichiasis.7 The lid defect was allowed to heal by spontaneous granulation without advancement or suturing. We have since extended the use of this simple, definitive technique to include more complex cases including patients with OCP, and we report our long-term outcomes.

Materials and methods

Seven consecutive patients underwent surgery (2006–2008) following informed consent and counselling regarding wound healing and permanent lash loss. OCP was diagnosed by conjunctival biopsy (in all but Case 7) and by its characteristic clinical appearances. Surgery was undertaken once disease was quiescent with or without treatment for a minimum of 3 months. The main outcome measures were absence of residual lashes post-operatively and absence of disease exacerbation in OCP cases.

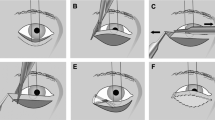

All surgeries were performed under local anaesthesia (50% mixture of 0.75% Chirocaine and 2% lignocaine with 1 : 100 000 adrenaline). An incision was made posterior to the aberrant lashes, usually at the grey line, and the anterior lamella (skin orbicularis) was dissected from the anterior tarsal surface. Two vertical cuts (4 mm high) were made at the medial (2 mm from puncta) and lateral ends, ensuring complete removal of the lash follicles. The anterior lamellar strip (skin, orbicularis oculi muscle and lash follicles) between the vertical incisions was excised. Haemostasis was achieved by pressure or light cautery, and the eyelids were dressed with Chloramphenicol ointment, paraffin gauze, and padded overnight. Post-operatively a short course of topical antibiotic (Chloramphenicol 0.5%) was prescribed. Patients were reviewed at 2, 6, and 12 weeks to monitor wound healing with spontaneous granulation and for a minimum of 6 months thereafter.

Results

Nine procedures were undertaken (three upper and six lower lids) in seven patients (average age, 70±22 years; 66.7% females). Patient details and surgical outcomes are presented in Table 1. Average follow-up period was 25.66±12 months (range: 9–43 months). Three of the seven patients needed further minor interventions. Single electrolysis procedures were carried out for an isolated lash at the medial edges of excised lamella in Cases 4 and 6. Residual lateral lashes in Case 1 were managed by further excision of remnant anterior lamella from the lateral edge of the lid. No residual misdirected lashes were present at 6 months follow-up in any of the patients. None of the cases showed exacerbation of inflammation or needed additional immunosuppression as a consequence of the lid surgery in the immediate post-operative period. The skin defects re-reepithelialised within 2–6 weeks in all patients with the newly formed lid having similar consistency to the normal lids with stable lid margins. Figure 1 shows the pre- and post-operative (1 week) lid appearance in Case 1.

Discussion

Outcomes with traditional treatment modalities for trichiasis are worse in cicatricial (27–56% success rate) vs non-cicatricial cases (70–90% success).3, 4 Cryotherapy in a quiet ‘white eye’ in 12 OCP patients was associated with minimal complications and no evidence of disease progression but only a 40% success rate at 12 months.2 Elder and Collin3 performed a conjunctival sparing anterior lamellar repositioning with grey line split in 16 upper lids of 11 OCP patients. Post-operatively two patients had disease exacerbation and there were five failures (31.3%). The same group used ‘Jones’ inferior retractor plication, again avoiding the conjunctiva, for lower lid entropion with trichiasis to counteract the contraction of the posterior lamella and additional mechanisms such as over-riding of the orbicularis and lid retractor laxity that are present in lower lid alongside the cicatricial disease.4 Six patients (42.8%) had persistent lash-globe touch after 14 procedures in 10 patients, one due to further inflammation and disease progression.

Our technique appears to be a promising alternative to more complicated procedures. Large areas of lashes including those at the lid corners can be treated with minimum risk of complications. Residual lashes as seen in three cases were less common later in the series. We consider these to be due to an initial conservative approach and part of our learning curve in this patient subgroup. We recommend extending the anterior lamellar excision (ALE) to lateral and medial lid edges to ensure complete lash follicle removal.

However, in certain cases mostly involving the upper eyelids, extent of ALE was limited to small areas of misdirected cilia with less than complete horizontal width of tarsus being exposed, this being especially important in cases with lid notching following previous interventions (Figure 1, Case 5). In our earlier technique, a 10 mm high anterior lamellar strip excised from the upper lids to correspond to the upper tarsus. This was decreased to 4 mm high strip in both upper and lower lids to reduce risk of lid retraction, hypertrophic scar, or even an entropion secondary to reduced anterior lamellar support. Laissez fairer healing in periocular region has been used for increasingly larger defects with satisfactory cosmetic and functional outcomes along with low rates of infection and wound contraction;8 and this was confirmed with our results. Absence of lashes was more obvious for upper lids than lower lids and if the procedure was unilateral due to asymmetry. Risk of lid lag and exposure is more likely in younger patients with less vertical lid laxity or in those with surgery on upper lids or both upper and lower lids simultaneously, and these are the scenarios in which we recommend proceeding with caution.

In conclusion, ALE with spontaneous granulation is a simple, safe, and effective technique for managing aberrant lashes, especially in patients with OCP. It can additionally be performed even in the primary care setting by the general ophthalmologist with excellent outcomes.

References

Hatton MP, Raizman M, Foster CS . Exacerbation of undiagnosed ocular cicatricial pemphigoid after repair of involutional entropion. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 24: 165–166.

Elder MJ, Bernauer W . Cryotherapy for trichiasis in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol 1994; 78: 769–771.

Elder MJ, Collin R . Anterior lamellar repositioning and grey line split for upper lid entropion in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Eye 1996; 10: 439–442.

Elder MJ, Dart JK, Collin R . Inferior retractor placation surgery for lower lid trichiasis in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol 1995; 79: 1003–1006.

Wojno TH . Lid splitting with lash resection for cicatricial entropion and trichiasis. Ophthal Plast reconstr Surg 1992; 8: 287–289.

Clorfeine GS, Kielar RA . Lash excision in trichiasis. Ann Ophthalmol 1977; 9: 525–528.

Moosavi AH, Mollan SP, Berry-Brincat A, Abbott J, Sutton GA, Murray A . Simple surgery for severe trichiasis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 23: 296–297.

DaCosta J, Oworu O, Jones CA . Laissez-Faire: How far can you go? Orbit 2009; 28: 12–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presentation: Data presented in part at a rapid fire presentation at Oxford Congress, 2009 and poster at Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Congress, Birmingham, 2009

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Eye website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kadyan, A., Barry, R. & Murray, A. Anterior lamellar excision and laissez-faire healing for aberrant lashes in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Eye 24, 990–993 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.268

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.268