Abstract

Klüver–Bucy syndrome (KBS) comprises a set of neurobehavioral symptoms with psychic blindness, hypersexuality, disinhibition, hyperorality, and hypermetamorphosis that were originally observed after bilateral lobectomy in Rhesus monkeys. We investigated two siblings with KBS from a consanguineous family by whole-exome sequencing and autozygosity mapping. We detected a homozygous variant in the heparan-α-glucosaminidase-N-acetyltransferase gene (HGSNAT; c.518G>A, p.(G173D), NCBI ClinVar RCV000239404.1), which segregated with the phenotype. Disease-causing variants in this gene are known to be associated with autosomal recessive Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC (MPSIIIC, Sanfilippo C). This lysosomal storage disease is due to deficiency of the acetyl-CoA:α-glucosaminidase-N-acetyltransferase, which was shown to be reduced in patient fibroblasts. Our report extends the phenotype associated with MPSIIIC. Besides MPSIIIA and MPSIIIB, due to variants in SGSH and NAGLU, this is the third subtype of Sanfilippo disease to be associated with KBS. MPSIII should be included in the differential diagnosis of young patients with KBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 1930s, Klüver and Bucy1 observed a syndrome of neurobehavioral symptoms after bilateral temporal lobectomy in Rhesus monkeys, which was later named Klüver–Bucy syndrome (KBS). Symptoms comprise (i) the inability to recognize the emotional significance of objects (psychic blindness), (ii) hypersexuality, (iii) altered emotional behavior (placidity), (iv) hyperorality and the ingestion of inappropriate objects, (v) an excessive tendency to react to every visual stimulus (hypermetamorphosis), (vi) aphasia and (vii) memory loss.2, 3 KBS can result from brain injury and from neurodegenerative disorders affecting the amygdalae.2 Children with disease-causing variants in the N-sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase (SGSH, OMIM*605270) and N-acetyl-α-d-glucosaminidase (NAGLU, OMIM*609701) genes suffer from neurodegeneration due to Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA (MPSIIIA, Sanfilippo A, OMIM#252900) and type IIIB (MPSIIIB, Sanfilippo B, OMIM#252920). These patients may exhibit symptoms resembling KBS including a volume loss of the amygdala.4, 5 Progression of MPSIII (including all subtypes A–D) is characterized by delay of language development (stage 1), behavioral disturbances and mental deterioration (stage 2), and finally a neurologic disorder with seizures and spasticity (stage 3).6

We applied autozygosity mapping and whole-exome sequencing (WES) to identify the genetic defect in two siblings with KBS from a consanguineous marriage. Both patients carried a homozygous disease-causing variant in the heparan-α-glucosaminide-N-acetyltransferase (HGSNAT, OMIM*610453) gene, which is responsible for autosomal recessive MPSIIIC (Sanfilippo C, OMIM#252930).

Subjects

IRB approval was obtained from the Charité (EA2/107/14). Guardians provided written informed consent for the study.

Patient III:01

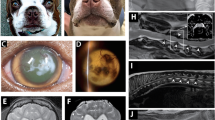

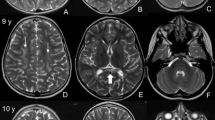

The girl was born to healthy consanguineous parents from Turkey. Her language development was retarded with first words spoken only by 2–3 years of age (NR 0.9–1.0 years). At 4 years she became restless. Global developmental delay was recorded at 6 years (MPSIII stage 1).6 At 8 years she lost her independence for self-care and suffered from sleep disturbance and aggressive behavior (MPSIII stage 2). Intellectual disability (IQ=70) became apparent at 9 years and hypersexuality at 13 years. Since 11.5 years she lived in a children’s home, and 2 years later was referred to a closed institution because of rapidly progressive restlessness in combination with prosopagnosia (face blindness), visual-sensory agnosia (psychic blindness), and hypermetamorphosis. At 18 years she became disinhibited and fearless (placidity), her spontaneous speech was limited to a few words, and her IQ had dropped below 20. She ‘ate anything she could get her hands on’ (hyperorality). As a young adult, seizures, unsteady gait, upper motoneuron signs, and global brain atrophy (Figure 1) became apparent (MPSIII stage 3).

(a–c) Cranial MRI of patient III:01 at the age of 30 years with cortical atrophy, especially around the Sylvian fissure (asterisk) and thickening of the calvarial bone (open arrowheads) due to a marked widening of the diploe portion. (d) Normal T2-weighted cranial MRI of patient III:04 at the age of 11 years. Progressive brain atrophy can be seen in the cranial CT-scans taken at 21 years (e) and 24 years (f) of age. Also in this patient, a marked thickening of the calvarial bone can be noted on the CT-scan.

Patient III:04

Her equally affected brother suffered from deafness and delayed speech development since infancy and became aggressive at the age of 9 years. His disorder developed similarly as in his sister. Detailed clinical features are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Methods

Positional gene mapping using SNP arrays

Autozygosity mapping was performed with DNA samples from patients (III:01, III:04, Figure 2e), unaffected siblings (III:02, III:03), and both parents (II:01, II:02) using the Axiom Genome-Wide Human EU Array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with ≈6 00 000 SNPs. Using HomozygosityMapper2012 (http://www.homozygositymapper.org [Mar2016]),7 we delineated the intervals that were (i) autozygous only in affected individuals (block length=200 SNPs) and excluded (ii) regions that were autozygous over >50 SNPs for the same allele in healthy individuals.

(a) Autozygosity map of the family using four unaffected and two affected family members. The red bars depict the autozygous regions at chromosomes 6 and 8. (b) Projection of the autozygous regions onto the banding pattern of chromosome 8 (red frames). (c) Genomic structure of the HGSNAT gene and location of the variant in exon 5. (d) Protein domain structure with 11 transmembrane domains (yellow) and the intralysosomal domain (purple) as modeled with TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/ [May2016]). The p.(G173D) amino acid exchange is located in the first transmembrane domain. (e) Pedigree of the consanguineous family depicting the genotype of each family member. (f) Electropherograms and the reading frame of the Sanger sequencing of a wildtype control and of patient III:04.

Exome sequencing

Exonic regions were enriched from DNA of patient III:04 with SureSelectv3 (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). WES of 101 bp single-end fragments was done on a HiSeq2000 machine (Illumina). A total of >98% of the 14 GB data reached the Q20-quality threshold. Fragments were aligned to the GRCh37.p11[hg19] reference sequence. For the 34 Mb coding regions of 19 126 RefSeq genes, >94% were covered >20 × by non-redundant reads. Sequence analysis was conducted by MERAP (https://sourceforge.net/projects/merap [Feb2015])8 and by MutationTaster2 (http://www.mutationtaster.org [Apr2016]).9

Sanger sequencing

All 18 coding exons of HGSNAT and flanking intronic regions were PCR-amplified and subjected to automatic sequencing (Supplementary Table 3). Sequences were compared to GenBank NM_152419.2. For verification of a splicing defect by RT-PCR, we generated cDNA from fibroblast RNA, amplified a 597 bp fragment (exons 9–14) with the primers: FW FAM-CTTCAAACATGCAAGTTGGAATG-3, REV 5-CCGAGCCTTGTAATACAATAGTATTT-3, and determined fragment sizes by capillary gel electrophoresis on an ABI3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) along with a GeneScan1000 ROX standard.

Measurement of enzyme activity

Acetyl-CoA:α-glucosaminidase-N-acetyltransferase (EC 2.3.1.3) enzyme activity was measured biochemically in fibroblasts from patient III:04 as described.10 Three control fibroblasts and a pathologic MPSIIIC control were measured alongside to secure batch-to-batch consistency. Briefly, cultured fibroblasts were incubated with substrate buffer (Moscerdam Substrates, Oegstgeest, NL, USA) in a 96-microtiter plate for 21 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the 4-methylumbelliferone moiety (4-MU) was released from the substrate and its fluorescence measured by fluorescence (Ex/Em=365/450 nm) against a calibration curve of 4-MU.

Results

Autozygosity mapping yielded the regions chr6:g.123 919 960—136 225 316 and chr8:g.40 484 239—82 336 285, chr8:g.117 641 610—128 407 443 comprising 12.3 and 52.6 Mbps (Figures 2a and b). WES discovered 60 673 variants that were covered >10 × and deviated from GRCh37.p11. As the parents were consanguineous, variants were filtered for a recessive inheritance model and removed if they occurred homozygously either in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database in >0.5% (http://exac.broadinstitute.org [Apr2016]; http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2015/10/30/030338 [Apr2016]) or in the 1000 Genomes project in >1% (http://www.1000genomes.org [May2016]) of the cases. 5624 variants remained. Of these 240 were homozygous, and 13 were located in the autozygous region. Of these variants, 6 were bioinformatically predicted to be potentially disease-causing (Supplementary Table 2). In HGSNAT we discovered two variants, one in the coding region of exon 5 (chr8:g.43 016 605G>A [GRCh37.p11], c.518G>A [NM_152419.2], p.(G173D), exons are numbered according to GenBank NG_009552.1) and one in the splice acceptor site of intron 11 (chr8:g.43 046 607C>A, c.1170-10C>A), however, a splicing defect could be excluded at the mRNA level where only a single 597 bp fragment was amplified from the cDNA of patient III:04 and controls. The c.518G>A variant has been reported in one unaffected heterozygous carrier (dbSNP137, rs370717845) of 6056 exomes (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ [Mar2016]), but was absent from the 1000 Genomes and from ExAC. The c.518G>A p.(G173D) variant affects the first transmembrane domain of the enzyme (Figure 2d) thereby disrupting an integral portion of the enzyme that connects the intralysosomal N-terminus with the first extralysosomal loop. The result was verified by Sanger sequencing and homozygosity segregated with the disease in the family (Figure 2e). Sanger sequencing of the entire coding region of HGSNAT in two additional unrelated single patients with KBS did not yield a disease-causing variant.

Enzymological studies

As additional proof of pathogenicity for the HGSNAT variant, we found diminished enzymatic activities in cultured fibroblasts of patient III.04 (0.09 nmol/h*mg). This result was below the activities determined in leukocytes from normal controls (0.2–1.3 nmol/h*mg, n=11), thereby corroborating the molecular diagnosis. The activities of three control fibroblast lines were within the normal range, whereas the activity of another MPSIIIC patient was 0.03 nmol/h*mg. The activity of the reference enzyme β-galactosidase was normal in the patient (4.81 nmol/min*mg, NR 1.9–11).

Discussion

We describe an HGSNAT variant as the cause of Klüver–Bucy syndrome with childhood onset. In adults KBS may result from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,11 bilateral temporal lobectomy,2 adrenoleukodystrophy,12 Alzheimer's disease,13 herpes encephalitis,14 and rapid correction of hyponatremia.2 In children KBS has been observed after herpes encephalitis,15 hypoxic insult,16 in neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis,17 MPSIIIA,4 MPSIIIB,5 and as a result of congenital bilateral anterior temporal malformation of the amygdalar-hippocampal complex.18

We report two siblings with MPSIIIC and severely altered emotional behavior who meet the diagnostic criteria for KBS with onset at MPSIII stage 2.6 This finding is in line with a two prospective studies on children with MPSIIIA and MPSIIB that were the first to describe an association between MPSIII and KBS.4, 5 A subset of the study group showed a decline of brain volume affecting more the amygdala than the hippocampus.4 This finding supports former observations on amygdalectomized versus hippocampectomized monkeys, suggesting that dysfunction of the amygdala is associated with many characteristic symptoms of KBS.19 However, as shown in further studies, KBS cannot solely be explained by dysfunction of the amygdala.13 A neuropathological study of the brains of two MPSIIIA and IIIC patients discovered ballooning of the neurons in the basal ganglia, the amygdala and the hippocampus.20 Other studies described hippocampus and amygdala variably21 or not at all13 to be affected in MPSIII (types A–D). In contrast, patients with KBS secondary to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Alzheimer’s disease revealed marked or moderate cell loss and gliosis of the amygdala.11, 13

Spasticity is a common symptom of MPSIII in the final stage.6, 22 In neuropathological studies on two patients with MPSIIIC cerebral atrophy and ballooning of the pyramidal cells including the Betz cells have been described.20 In our study, patient III:01 and to a lesser degree her younger affected brother III.04 developed global brain atrophy and a Babinski sign indicating the development of upper motoneuron signs at the final stage of MPSIIIC.

In conclusion, patients with MPSIIIC can establish the full spectrum of KBS. As pointed out by Potegal et al.4 and Shapiro et al.,5 MPSIII is the first inherited pediatric disease presenting systematically with clinical features of KBS.

References

Klüver H, Bucy PC : Preliminary analysis of functions of the temporal lobes in monkeys. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1939; 42: 979–1000.

Hayman LA, Rexer JL, Pavol MA, Strite D, Meyers CA : Klüver–Bucy syndrome after bilateral selective damage of amygdala and its cortical connections. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10: 354–358.

Lilly R, Cummings JL, Benson DF, Frankel M : The human Klüver–Bucy syndrome. Neurology 1983; 33: 1141–1145.

Potegal M, Yund B, Rudser K et al: Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIA presents as a variant of Klüver–Bucy syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2013; 35: 608–616.

Shapiro E, King K, Ahmed A et al: The neurobehavioral phenotype in mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB: an exploratory study. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2016; 6: 41–47.

Cleary MA, Wraith JE : Management of mucopolysaccharidosis type III. Arch Dis Child 1993; 69: 403–406.

Seelow D, Schuelke M : HomozygosityMapper2012—bridging the gap between homozygosity mapping and deep sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40: W516–W520.

Hu H, Wienker TF, Musante L et al: Integrated sequence analysis pipeline provides one-stop solution for identifying disease-causing mutations. Hum Mutat 2014; 35: 1427–1435.

Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D : MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods 2014; 11: 361–362.

Lukacs Z. Mucopolysaccharides; in: Blau N, Duran M, Gibson KM (eds): Laboratory Guide to the Methods in Biochemical Genetics. Springer: Heidelberg, 2008, pp 287–324.

Dickson DW, Horoupian DS, Thal LJ, Davies P, Walkley S, Terry RD : Klüver–Bucy syndrome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case report with biochemistry, morphometrics, and Golgi study. Neurology 1986; 36: 1323–1329.

Powers JM, Schaumburg HH, Gaffney CL : Klüver–Bucy syndrome caused by adreno-leukodystrophy. Neurology 1980; 30: 1231–1232.

Boccardi M, Pennanen C, Laakso MP et al: Amygdaloid atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett 2002; 335: 139–143.

Marlowe WB, Mancall EL, Thomas JJ : Complete Klüver–Bucy syndrome in man. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav 1975; 11: 53–59.

Pradhan S, Singh MN, Pandey N : Kluver–Bucy syndrome in young children. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1998; 100: 254–258.

Tonsgard JH, Harwicke N, Levine SC : Kluver–Bucy syndrome in children. Pediatr Neurol 1987; 3: 162–165.

Lanska DJ, Lanska MJ : Klüver–Bucy syndrome in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J Child Neurol 1994; 9: 67–69.

Pestana EM, Gupta A : Fluctuating Kluver–Bucy syndrome in a child with epilepsy due to bilateral anterior temporal congenital malformations. Epilepsy Behav EB 2007; 10: 340–343.

Murray EA, Mishkin M : Amygdalectomy impairs crossmodal association in monkeys. Science 1985; 228: 604–606.

Martin JJ, Ceuterick C, Van Dessel G, Lagrou A, Dierick W : Two cases of mucopolysaccharidosis type III (Sanfilippo). An anatomopathological study. Acta Neuropathol 1979; 46: 185–190.

Tamagawa K, Morimatsu Y, Fujisawa K, Hara A, Taketomi T : Neuropathological study and chemico-pathological correlation in sibling cases of Sanfilippo syndrome type B. Brain Dev 1985; 7: 599–609.

Valstar MJ, Ruijter GJG, van Diggelen OP, Poorthuis BJ, Wijburg FA : Sanfilippo syndrome: a mini-review. J Inherit Metab Dis 2008; 31: 240–252.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their parents for participation in the study and Angelika Zwirner for excellent technical assistance. The project was funded by the Max-Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Department of Human Molecular Genetics, by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 665 TP C4) to MS, and the NeuroCure Center of Excellence (Exc 257) to MS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, H., Hübner, C., Lukacs, Z. et al. Klüver–Bucy syndrome associated with a recessive variant in HGSNAT in two siblings with Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC (Sanfilippo C). Eur J Hum Genet 25, 253–256 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2016.149

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2016.149