Abstract

Supporting consultands to communicate risk information with their relatives is key to obtaining the full benefits of genetic health care. To understand how health-care professionals address this issue in clinical practice and what interventions are used specifically to assist consultands in their communication of genetic information to appropriate relatives, we conducted a systematic review. Four electronic databases and four subject-specific journals were searched for papers published, in English, between January 1997 and May 2014. Of 2926 papers identified initially, 14 papers met the inclusion criteria for the review and were heterogeneous in design, setting and methods. Thematic data analysis has shown that dissemination of information within families is actively encouraged and supported by professionals. Three overarching themes emerged: (1) direct contact from genetic services: sending letters to relatives of mutation carriers; (2) professionals’ encouragement of initially reluctant consultands to share relevant information with at-risk relatives and (3) assisting consultands in communicating genetic information to their at-risk relatives, which included as subthemes (i) psychoeducational guidance and (ii) written information aids. Findings suggest that professionals’ practice and interventions are predicated on the need to proactively encourage family communication. We discuss this in the context of what guidance of consultands by professionals might be appropriate, as best practices to facilitate family communication, and of the limits to non-directiveness in genetic counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supporting consultands of genetic services to effectively communicate information about genetic risks with their relatives is key to obtaining the full benefits of genetic health care.1 Genetic health practitioners typically rely on the proband (or, for child probands, the parents) to inform relatives about their potential at-risk status. Passing on such information can be problematic, which may prevent relatives from making informed choices regarding risk management of the disease and life planning decisions.2 Individual characteristics and patterns of family behaviour and relationships, disease characteristics and cultural factors may withhold or delay disclosure of genetic information to at-risk relatives, even when consultands see this as their personal responsibility.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Although guidelines recommend that professionals should not contact family members directly, that also state that professionals should actively encourage consultands to transmit relevant risk information to relatives and support them throughout the communication process; however, there is lack of clarity regarding how this should be done.8, 9 There has been some discussion on how to cascade information about genetic health risks to the relatives of patients with familial hyper-cholesterolaemia, including the active contacting of relatives directly by professionals, although this depends entirely upon information provided by the proband.10 With genetic diseases increasingly treatable and preventable, some recommend a more proactive role of genetic professionals.11, 12

A potential obstacle to professional encouragement of family communication may be too great a respect for the principle of non-directiveness, when understood as the rather unhelpful notion of simply having to give the patient what they ask for.13 An adequate notion of non-directiveness puts emphasis on the need sometimes to challenge the statements, attitudes and beliefs of the consultand or patient.14, 15 Thus, too great an emphasis on respect for the patient’s wish not to disclose information to relatives or the relatives’ wish not to know may become a barrier to disclosure. This raises ethical issues for health professionals and services, as their degree of responsibility for ensuring relatives’ awareness of their risks – and the extent to which they should be proactive in this task – have long been debated in genetic health care.16, 17

Previous reviews have been published on the process and outcomes of communication of genetic information within families,18, 19, 20 including the communication between children and their parents,21 the factors influencing patterns of intrafamilial communication and awareness,22, 23 and on the analysis of the communication between genetic specialists and patients.24 However, to our knowledge there has been no systematic review of studies that have analysed how family communication of information about genetic risks is addressed in genetic counselling practice. This study aims to address that gap.

To inform discussion on the facilitation of family communication about genetics, it is relevant to examine how genetic health-care professionals deal with this issue in clinical practice. This systematic review aims to identify and critically reflect on the research evidence available on this topic with the objective of answering the following questions: (1) How and by what means is family communication about genetics approached in genetic counselling practice? (2) What are the actions taken by the professionals involved? (3) What are the characteristics and contents of the interventions specifically assisting consultands in their communication of genetic information to their relatives?.

Materials and methods

This systematic review follows the process developed by the PRISMA statement,25 including the definition of the relevant search terms, selection of studies based on clear inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality appraisal of papers.

Search strategy

The electronic databases PubMed, Academic Search Complete-EBSCO, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar were searched focussing on articles published in English between January 1997 (after direct mutation detection became available and pre-symptomatic testing protocols were generally adopted)26 and May 2014. The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles and was performed between January and May 2014. A preliminary search was performed to determine the appropriate search terms; after experimentation, the following terms were defined and searched: genetic counsel(l)ing OR genetic services AND health professional OR genetic counsel(l)or OR geneticist AND family OR relatives OR kin OR offspring AND communicat* OR disclos* OR transmi* OR shar*.

In addition, the indexes of four relevant journals (Journal of Genetic Counseling, American Journal of Medical Genetics, Clinical Genetics and European Journal of Human Genetics), as well as reference lists and key-author searches were hand-searched to identify additional relevant articles missed by this search strategy. Studies were selected and reviewed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Data evaluation

A total of 2926 papers were initially identified as potential papers for inclusion. Of these, 372 were duplicates, leaving 2554 papers for examination. One additional paper was identified in the hand-search. Based on the titles and abstracts of the remaining papers, 2521 were excluded, leaving a total of 34 papers. The full papers of these studies were obtained. After complete reading by the first and second authors, 20 papers were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1). A total of 14 remaining papers met the inclusion criteria. All these remaining papers were eligible for quality appraisal.

All titles and abstracts of the identified studies were independently assessed by two authors (AM and MP) for inclusion or exclusion in the review. Papers were excluded when both reviewers agreed that inclusion criteria were not met. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Eligible papers were assessed for their quality using the tool suggested by Kmet et al.27 This tool is suitable for evaluation of both quantitative and qualitative studies, using two types of checklists for the studies’ appraisal. For each paper, a score between 0 and 2 was assigned against each question (‘yes’=2, ‘partial’=1, ‘no’=0). For studies using mixed-methods design, we decided to score the papers using both qualitative and quantitative checklists. Authors (AM and MP) independently assessed each paper and then met to discuss scores; areas of disagreement were discussed until consensus was reached. As the tool does not specify a cutoff score to discard poor quality papers, we decided to adopt the criteria already followed by Skirton et al,28 where a cutoff point of 60% was defined. The reported score is the mean score of the assessments made by the authors.

Data analysis

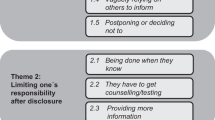

Relevant data were extracted from the 14 studies included and were compiled in Table 2 (see Supplementary Material). A meta-analysis of the data would not be feasible given the variability among studies regarding study design, interventions and populations. A thematic analysis was conducted to synthesize the data qualitatively, aiming to identify overarching themes through an iterative process of examining data displayed in the studies to identify themes or patterns.29 Data are presented in narrative form. The analytic process was enabled through ongoing discussion between the authors (AM and MP). Three overarching themes emerged from the analysis of the data: (1) direct contact from genetic services: letters sent to relatives of mutation carriers; (2) professionals’ encouragement of initially reluctant consultands to share relevant information with at-risk relatives and (3) assisting consultands in the communication of information to at-risk relatives, which includes subthemes (i) psychoeducational guidance and (ii) written information aids.

Results

Description of the data

Data from the studies included are presented in Table 2. The countries of origin of the 14 studies included in the review are: 6 – United States, 2 – The Netherlands, 2 – Australia, 1 – Sweden, 1 – United Kingdom and 1 – Finland; 1 multisite study, involving both the United Kingdom and Australia. The focus of the studies regarding type of disease was: 6 – hereditary cancers; 5 – combination of adult-onset inherited conditions; 1 – combination of paediatric single gene conditions; 1 – inherited cardiac disease, and 1 – inherited hereditary cholesterol. Regarding methods, studies used: 8 – quantitative methods (5 – survey-based and 3 – clinical intervention studies); 3 – qualitative methods; 2 – mixed-methods; 1 – randomised controlled trial. Sample/participant sizes ranged from 16 to 626 participants. 9 studies were published between 2000 and 2010, and 5 since 2011.

Themes that emerged from the studies

Direct contact from genetic services: letters sent to relatives of mutation carriers

This theme comprises two papers30, 31 presenting studies in which services/professionals directly contact the family members potentially at-risk. The two papers explore the acceptability and feasibility of direct contact by genetic services to high-risk relatives informing them about the availability of genetic counselling and testing. Direct contact consisted in sending a letter to relatives of mutation-positive consultands. In both studies, the wording of the letters was in general terms and neither identified the proband nor provided details about the disease; the time of sending this letter was decided with the proband. No privacy or autonomy concerns were reported by participants (the recipients of the letter). For those relatives who contacted the genetic services seeking further information, genetic counselling comprised the exploration of the pedigree and discussions about advantages and disadvantages of genetic testing, including possible psychological reactions and employment and insurance issues. Post-test counselling was arranged and mutation carriers were referred for surveillance measures. Results of these studies show high levels of acceptability for genetic services to notify high-risk relatives directly. This was corroborated by the absence of adverse psychosocial and legal reactions, and the higher uptake of genetic services to clarify their status by at-risk relatives contacted directly than by those informed by family members.

Professionals’ encouragement of initially reluctant consultands to share relevant information with at-risk relatives

This theme arose in three papers with studies focussing on active nondisclosure, that is, situations where consultands explicitly refuse to pass relevant risk information to their relatives.32, 33, 34 Professionals’ practice included encouragement of consultands about the appropriateness of sharing relevant risk information with at-risk relatives, but without coercion. In cases of explicit nondisclosure, professionals’ tried to persuade consultands to disclose relevant information to relatives, including:32 further discussion with the consultand (to reinforce the importance of disclosure and to clarify the consultands’ reasons for nondisclosure), involving more experienced colleagues in the discussions with the consultand, and using written reminders as efforts to encourage disclosure; in no circumstance was coercion reported. Professionals also reported having reflected upon the possibility of notifying at-risk relatives without the consultands’ consent,33, 34 for which colleagues’ advice, formal case discussion at a conference presentation and using legal consultants and institutional review boards were the most frequently utilised resources to inform their decision. The actual disclosure of information to relatives without the consultand’s permission was reported by professionals as either having not occurred32 or only rarely.33, 34

Assisting consultands in the communication of information to at-risk relatives

This theme comprises nine papers with studies focussing on professionals’ practice35, 36, 37 and specific interventions to assist consultands in the communication of information to at-risk relatives.38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Features of practice included psychoeducational guidance and information aids that were used as adjuncts to clinical practice.

Psychoeducational guidance. These strategies were facilitated by genetic counsellors and by a specialist nurse, and were provided in addition to the standard pre-disclosure genetic counselling sessions, and by phone 2–4 weeks and 3–6 months after result disclosure. Guidance strategies included the provision of supportive and informative elements: face-to-face explanation of the pedigree and risks and asking consultands to estimate their risk and identify at-risk relatives; education about the familial implications and risks of a genetic diagnosis; exploration of the perceived obstacles to passing on information to at-risk relatives; encouragement and ‘instruction’ to communicate with relatives, and offering follow-up support for consultands; in cases of (non)communication between parents and children or young adults, tailoring the content of the information to the children’s age and stage of development, asking the parent’s opinion about how information should be shared. Buckman’s ‘breaking bad news’ model44 was used as a communication skills-building intervention to educate and assist consultands in the disclosure process, including the exploration of the relatives’ level of knowledge about their at-risk status, their willingness to know about it and responding to the relatives’ reactions.

Written information aids. Various information aids were used, either given to consultands at the consultation or sent to their homes according to the proband’s preference. Materials were produced by professionals from patient organizations and revised by doctors and patients known by the organization, or by physicians and genetic counsellors from the clinical institutions. Tools mainly consisted of letters, leaflets/brochures or resource guides. Materials were also made available through packages/binders integrating separate components containing the following information: clinical implications about the specific disease; recommendations for surveillance and prevention; the importance of family history; the benefits and limitations of testing; guidance on how to inform relatives; a letter to family members stating that a disease-causing mutation was identified in their relative; a fact sheet with frequently asked questions about disease risk, costs of genetic testing and insurance issues; contact information for genetic counsellors specific to each eligible relative according to their geographic residence; information about support websites and a CD version of all the documents provided. Personalized medical information was also made available, for example, including copies of the pedigree and medical reports, and videotapes from the initial genetic counselling session.

Discussion

This review summarises the findings of 14 studies related to the practice of health professionals in clinical genetics and and genetic counselling services on the issue of communication of genetic information within families. Although studies were heterogeneous in design and setting, the findings of this review identified three overarching themes representing how family communication about genetics is addressed in practice.

The dissemination of information within families has been shown to be actively encouraged and supported in genetic counselling professionals, following the published guidelines and recommendations from various professional bodies.8 In cases of active nondisclosure, a policy of active encouragement and persuasion characterises the professionals’ role and only very rarely do professionals override their patients’ confidentiality. This suggests that consultands are commonly willing to disclose genetic information to their family members, even though difficulties may be felt on how to actually communicate rather than on deciding whether they wish to inform them. For those requiring support or showing difficulties in this process, there is psychoeducational guidance, and written information aids are available as means through which professionals can assist their consultands in the communication process. These interventions were generally effective ‘cues for action’ both in terms of intrafamilial disclosure of genetic information and of genetic testing uptake among at-risk relatives. There is also a more direct approach to family communication, whereby genetics services send informative letters to at-risk relatives informing them of their risks and the availability of genetic counselling services for further information. This approach was fully acceptable to the relatives, and effective in promoting further clarification of at-risk relatives’ genetic status.

Most of the practices reviewed were part of research interventions rather than describing the relevant routine practices among genetic health professionals. The studies have described the various ways of addressing the issue of family communication about genetics in practice, ranging from more process-focused approaches (such as direct contact) to others that privilege the provision of specific guidance, but they include few details of the actions taken by professionals and of their strategies for facilitating family communication. Most of the interventions used to support patients to communicate genetic information to their relatives focused on information content (as in the ‘deficit’ model of the public understanding of science) and were delivered as a single transaction with consultands, whereas in only two cases did follow-up contact occur.

Some of the intervention studies in this review are predicated on the need to encourage family communication, and that it would be in the interests of other family members for the consultand to disclose information about him/herself because their relatives may find it helpful to know about their risk of developing a genetic disorder. The issue of family communication in genetic health care may be regarded as an area where a strict adherence to a narrow, ‘shallow’ conception of non-directiveness may be inappropriate, and where the explicit confrontation of the consultands with information or with a call to consider the potential outcomes of a range of hypothetical scenarios, in which they have made different decisions, could be seen as ‘appropriate directiveness’.15

Family communication depends on a plethora of factors that go beyond consultands’ motivations and the pre-determined actions of professionals within genetic counselling. Furthermore, measures of the number of relatives contacting genetic services or the uptake of testing are not necessarily indicative of communication within families. Recent counselling-oriented interventions aimed at facilitating family communication about genetic information are currently being implemented, aiming at fostering patients’ autonomy and their self-efficacy towards making informed decisions.45, 46, 47 Although it may be unhelpful to impose an operational definition of what addressing family communication about genetics in practice should be, without such a definition the question of what guidance of consultands by professionals might be appropriate remains unclear. Whereas an accurate understanding of information is key for the appropriate communication with relatives and the consultand’s autonomous decision-making (nondirective), counselling on this specific topic does not mean just presenting full and unbiased information as something that can be passed, unaltered, from person to person in the family; this is especially salient in families where parents are considering whether and how to communicate genetic information to their young adult children. As others have argued,1, 18 family communication about genetics is a multistage process that requires genetic information to be understood beyond simplistic models of communication. The voicing by both consultand and professionals of their perspectives and some dialogue about the differences has been proposed as a helpful way for professionals to consider when it may be unhelpful and inappropriate for them to challenge the consultand and where, in contrast, it may be very useful for them to contribute more proactively with their perspective, without coercion and without denying the critical importance of the patient’s wider value systems.13

Implications for practice and further research perspectives

Perhaps rather than focussing on the content of the information to be given in genetic consultations, engaging with the consultand in a reflective consideration of the relevance and value of transmitting risk information to those relatives identified as at potentially high risk, and exploring the family dynamics and patterns of communication, as well as the possible nature and causes of poor communication within families, may provide more targeted support and facilitate more open communication within the family.38, 46 The complexity of family functioning perhaps makes it more fruitful and more ethical for professionals to be open to address these issues using more contextual strategies.18 The family genetic risk communication framework48 may be of help in the clinical context as an orienting tool to work with consultands through their communication process. Clinical genetic services and the health-care system more broadly might also want to consider the specificities of the communication throughout the family’s life cycle,49 namely between parents and children/young adults,50 both in the context of genetic counselling practice and in the facilitation of family-oriented psychosocial support.51, 52 Future research including process studies and observational studies could contribute to the better understanding of how family communication about genetics is specifically addressed in genetic counselling, namely the actual strategies and responses used by genetic health professionals. Further research should also discuss these data with genetic health-care professionals and with members of families affected by inherited conditions, aiming to look at the advantages and pitfalls of these approaches.

Limitations

Some limitations need to be considered within this review. Given that in this review, only English language studies published in scholarly peer-reviewed journals were included, unpublished data or data published by other means or in other languages that could have contributed to a better understanding of this topic were not analysed. These biases therefore regrettably privilege those studies conducted in countries where the English language is well established and where research funding is available and this impedes access to different cultural and socioeconomic research contexts.

References

Gaff C, Bylund C (eds): Family Communication About Genetics: Theory and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Parker M, Lucassen A : Concern for individuals and families in clinical genetics. J Med Ethics 2003; 29: 70–73.

Forrest K, Simpson S, Wilson B et al: To tell or not to tell: barriers and facilitators in family communication about genetic risk. Clin Genet 2003; 64: 317–326.

Wilson BJ, Forrest K, Teijlingen ER et al: Family communication about genetic risk: the little that is known. Community Genet 2004; 7: 15–24.

Hallowell N, Foster C, Eeles R, Ardern-Jones A, Murday V, Watson M : Balancing autonomy and responsibility: The ethics of generating and disclosing genetic information. J Med Ethics 2003; 29: 74–83.

Featherstone K, Atkinson P, Bharadwaj A, Clarke AJ : Risky Relations: Family, Kinship and the New Genetics. Oxford: Berg, 2006.

Gaff CL, Collins V, Symes T, Halliday J : Facilitating family communication about predictive genetic testing: probands' perceptions. J Genet Couns 2005; 14: 133–140.

Forrest LE, Delatycki MB, Skene L, Aitken M : Communicating genetic information in families—a review of guidelines and position papers. Eur J Hum Genet 2007; 15: 612–618.

Black L, McClellan KA, Avard D, Knoppers BM : Intrafamilial disclosure of risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Points to consider. J Community Genet 2013; 4: 203–214.

Newson AJ, Humphries SE : Cascade testing in familial hypercholesterolaemia: How should family members be contacted? Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 401–408.

Battistuzzi L, Ciliberti R, Forzano F, De Stefano F : Regulating the communication of genetic risk information: The Italian legal approach to questions of confidentiality and disclosure. Clin Genet 2012; 82: 205–209.

Otlowsky M : Australian reforms enabling disclosure of genetic information to genetic relatives by health practitioners. J Law Med 2013; 21: 217–234.

Elwyin G, Gray J, Clarke AJ : Shared decision making and nondirectiveness in genetic counselling. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 135–138.

Wolff G, Jung C : Nondirectiveness and genetic counseling. J Gen Couns 1995; 4: 3–25.

Clarke AJ : The process of genetic counselling: Beyond nondirectiveness. In: Harper P, Clarke AJ (eds): Genetics, Society and Clinical Practice. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers, 1997, pp 179–200.

Clarke AJ : Challenges to genetic privacy: The control of personal genetic information. In: Harper P, Clarke AJ (eds): Genetics, Society and Clinical Practice. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers, 1997, pp 149–164.

Hodgson J, Gaff C : Enhancing family communication about genetics: ethical and professional dilemas. J Genet Couns 2013; 22: 16–21.

Gaff CL, Clarke AJ, Atkinson P et al: Process and outcome in communication of genetic information within families: A systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet 2007; 15: 999–1011.

Wiseman M, Dancyger C, Michie S : Communicating genetic risk information within families: a review. Fam Cancer 2010; 9: 691–703.

Seymour K, Addington-Hall J, Lucassen A, Foster C : What facilitates or impedes family communication following genetic testing for cancer risk? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of primary qualitative research. J Genet Couns 2010; 19: 330–342.

Metcalfe A, Coad J, Plumridge GM, Gill P, Farndon P : Family communication between children and their parents about inherited genetic conditions: A meta-synthesis of the research. Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 1193–1200.

Atkinson P, Featherstone K, Gregory M : Kinscapes, genescapes & timescapes: families living with genetic risk. Sociol Health Illn 2013; 35: 1227–1241.

Nycum G, Avard D, Knoppers BM : Factors influencing intrafamilial communication of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic information. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 872–880.

Paul J, Metcalfe S, Stirling L, Wilson B, Hodgson J : Analyzing communication in genetic consultations—a review. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98: 15–33.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG,, The PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: 1000097.

Tibben A : Predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. Brain Res Bull 2007; 72: 165–171.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS : Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2004.

Skirton H, Cordier C, Ingvoldstad C, Taris N, Benjamin C : The role of the genetic counsellor: a systematic review of research evidence. Eur J Hum Genet 2014; 23: 452–458.

Braun V, Clarke V : Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101.

Aktan-Collan K, Haukkala K, Pylvänäinen K et al: Direct contact in inviting high-risk members of hereditary colon cancer families to genetic counselling and DNA testing. J Med Genet 2007; 44: 732–738.

Suthers GK, Armstrong J, McCormack J, Trott D : Letting the family know: Balancing ethics and effectiveness when notifying relatives about genetic testing for a familial disorder. J Med Genet 2006; 43: 665–670.

Clarke AJ, Richards M, Kerzin-Storrar L et al: Genetic professionals' reports of nondisclosure of genetic risk information within families. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 556–562.

Falk MJ, Dugan RB, D'Riondan MA, Matthews AL, Robin NH : Medical geneticists' duty to warn at-risk relatives for genetic disease. Am J Med Genet 2003; 120A: 374–380.

Dugan RB, Wiesner GL, Juengst ET et al: Duty to warn at-risk relatives for genetic disease: genetic counselors' clinical experience. Am J Med Genet 2003; 119C: 27–34.

Gallo AM, Angst DB, Knafl KA, Twomey JG, Hadley E : Health care professionals' views of sharing information with families who have a child with a genetic condition. J Genet Couns 2010; 19: 296–304.

Stol YH, Menko FH, Westerman MJ, Janssens RM : Informing family members about a hereditary predisposition to cancer: Attitudes and practices among clinical geneticists. J Med Ethics 2012; 36: 391–395.

Forrest LE, Delatycki MB, Curnow L, Skene L, Aitken MA : Genetic health professionals and the communication of genetic information in families: Practice during and after a genetic consultation. Am J Med Genet 2010; 152A: 1458–1466.

Montgomery SV, Barsevick AM, Egleston BL : Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: Report of a randomized control trial. Fam Cancer 2013; 12: 537–546.

Roshanai AH, Rosenquist R, Lampic C, Nordin K : Does enhanced information at cancer genetic counseling improve counselees' knowledge, risk perception, satisfaction and negotiation of information to at-risk relatives? A randomized study. Acta Oncol 2009; 48: 999–1009.

Forrest LE, Burke J, Bacic S, Amor DJ : Increased genetic counseling support improves communication of genetic information in families. Genet Med 2008; 10: 167–172.

Van der Roest WP, Pennings JM, Bakker M, Van den Berg MP, Tintelen PV : Family letters are an effective way to inform relatives about inherited cardiac disease. Am J Med Genet 2009; 149A: 357–363.

Van den Nieuwenhoff H, Mesters I, Nellissen J, Stalenhoef AF, de Vries NK : The importance of written information packages in support of case-finding within families at risk for inherited high cholesterol. J Genet Couns 2006; 15: 29–40.

Kardashian A, Fehniger, Creasman J, Cheung E, Beattie MS : A pilot study of the Sharing Risk Information Tool (ShaRIT) for families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2012; 10: 4.

Buckman R : How to Break Bad News: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1992.

de Geus E, Aalfs CM, Verdam M, de Haes H, Smets E : Informing relatives about their hereditary or familial cancer risk: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014; 15: 86.

Gaff C, Hodgson J : A genetic counseling intervention to facilitate family communication about inherited conditions. J Genet Couns 2014; 23: 814–823.

Hodgson J, Metcalfe SA, Aitken MA et al: Improving family communication after a new genetic diagnosis: a randomized controlled trial of a genetic counseling intervention. BMC Med Genet 2014; 15: 33.

Wiens ME, Wilson BJ, Honeywell C, Etchegary H : A family risk communication framework: Guiding tool development in genetics health services. J Community Genet 2013; 4: 233–242.

Rolland J, Williams J : Toward a biopsychosocial model for 21st-century genetics. Fam Proc 2005; 44: 3–24.

Metcalfe A, Plumridge G, Coad J, Shanks A, Gill P : Parents’ and children’s communication about genetic risk: a qualitative study, learning from families’ experiences. Eur J Hum Genet 2011; 19: 1–7.

Rowland E, Hutchison S, Jackson C et al: Co-designing an intervention to facilitate family communication about inherited genetic conditions (IGC). Eur Soc Hum Genet Confer 2014.

Mendes Á, Chiquelho R, Santos TA et al: Supporting families in genetic counselling services: a multifamily discussion group for at-risk cancer families. J FamTher 2015; 37: 343–360.

Acknowledgements

AM (SFRH/BPD/88647/ 2012) and MP (SFRH/BPD/66484/2009) were the recipients of postdoctoral grants from FCT (the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology). We thank João Silva (CGPP, IBMC) for his critical reading on earlier drafts of this manuscript, and Anabela Costa, library consultant at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Porto, for her consultation with the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendes, Á., Paneque, M., Sousa, L. et al. How communication of genetic information within the family is addressed in genetic counselling: a systematic review of research evidence. Eur J Hum Genet 24, 315–325 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.174

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.174

This article is cited by

-

The experience of receiving a letter from a cancer genetics clinic about risk for hereditary cancer

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Personalising genetic counselling (POETIC) trial: Protocol for a hybrid type II effectiveness-implementation randomised clinical trial of a patient screening tool to improve patient empowerment after cancer genetic counselling

Trials (2023)

-

Direct letters to relatives at risk of hereditary cancer—study protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial of healthcare-assisted versus family-mediated risk disclosure at Swedish cancer genetics clinics (DIRECT-study)

Trials (2023)

-

Interventions to support patients with sharing genetic test results with at-risk relatives: a synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM)

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

“I have always lived with the disease in the family”: family adaptation to hereditary cancer-risk

BMC Primary Care (2022)