Abstract

The results of genome-wide association studies have revealed that most human complex diseases (for example, cancer, diabetes and psychiatric disorders) are affected by a large number of variants, each of which explains a small increase in disease risk, suggesting a pattern of polygenic inheritance. At the same time, it has been argued that most complex diseases are genetically heterogeneous because many sporadic cases are observed, as well as cases with a family history. In this study, under the assumption of polygenic inheritance, we derive the expected proportion of sporadic cases using analytical methods and simulation. We show how the proportion of sporadic cases depends on disease prevalence (K) and heritability on the underlying liability scale (hL2). We predict the underlying heritability and the proportion of sporadic cases for a range of human complex diseases, and show that this proportion is typically large. For a disease with hL2=63% and K=0.4%, such as schizophrenia, >83% of proband cases are predicted to be sporadic (no affected first-, second- and third-degree relatives) in typical families (on an average, two children per couple). For the majority of these diseases, a large proportion of sporadic cases is expected under the polygenic model, implying that the observed large proportion of sporadic cases is not informative to the causal mechanism of a complex genetic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-scale, high-density genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have greatly facilitated the discovery of genetic variants that affect the predisposition to human complex diseases.1 The results of recent GWAS suggest that the majority of susceptible loci have small contributions to phenotypic variation, which indicates that there should be a large number of susceptibility loci involved in the genetic basis of complex disease.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 These findings are consistent with the polygenic model, proposed almost a century ago,9 underlying the genetic etiology of complex diseases. At the same time, on the basis of the knowledge of family history, differentiation is often made between sporadic and familial cases. This differentiation implies some sort of genetic heterogeneity, either that environmental factors are more important in sporadic cases or that sporadic cases arise from new mutations of large effect size. Integrating this differentiation into an understanding of the genetic architecture of complex disease depends on the frequency of sporadic cases, consistent with the polygenic model.

In this study, we investigate the relative proportion of sporadic and familial cases expected under the polygenic threshold model. We assume that disease susceptibility is genetically homogeneous in the population and the observed illness results from the accumulative effect of multiple common genetic and environmental effects that exceeds a certain threshold.10, 11, 12, 13 We conducted a simulation study to calculate the probability of a proband case without family history. Furthermore, we investigated the relationship of disease prevalence, heritability of liability, recurrence risk (RR) and family size, and analytically predicted heritability of liability and the proportion of sporadic cases in human complex diseases under the polygenic model.

Methods and results

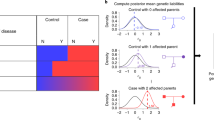

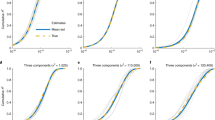

We simulated pedigrees with three generations. For each pair of parents in the first and second generations, the number of offspring was independently drawn from a Poisson distribution, as in Cui and Hopper.14 The structure of the simulated pedigree is illustrated in Figure 1. The disease liability (y) of each individual in the pedigree was simulated by a simple genetic model y=a+e, where a is the additive genetic effect; e is the environmental effect; e ∼ N(0, h2L); and hL2 is the narrow sense heritability of liability. The additive effects of the individuals in the first generation were drawn from a ∼ N(0, h2L), whereas those in the second and third generations were generated by a=0.5aF+0.5aM+m, where aF and aM are the additive effects of parents, and m is the effect due to Mendelian segregation, m ∼ N(0, 0.5h2L) (Appendix). A range of heritability levels (hL2=0, 10,…100%), along with three levels of disease prevalence (K=10, 1 and 0.1%), was considered to be representative of human complex diseases. An individual was considered to be diseased if y>T, where T is the threshold on the normal distribution truncating the proportion K. A total of 100 000 pedigrees with at least one disease case (proband) in the third generation were generated for each of combinations of hL2, K and S, where S is the mean family size per couple. A proband case was considered to have a family history of disease on the basis of two different definitions: (I) at least one first-degree relative with disease, and (II) at least one first-, second- or third-degree (1°, 2° or 3°, illustrated in Figure 1) relative is affected, and the probability of a sporadic case was defined accordingly.

It is shown in Figure 2 that P(sporadic) depends mainly on disease prevalence K. It increases markedly with decreasing K, and gradually increases with decreasing hL2 and S. For a disease with a prevalence of 0.1%, a proband case has a probability of ∼78% (definition I) or ∼70% (definition II) to be sporadic, even if the heritability of disease is 100% and family size is large (S=5). We investigated the relationship between the underlying and observed scale. In theory, P(sporadic) is approximately equal to  where

where  is standard normal cumulative distribution function; fn is the number of nth-degree relatives;

is standard normal cumulative distribution function; fn is the number of nth-degree relatives;  with i=z/K; and z is the height of the standard normal curve at the truncation point T (Appendix). For example, when S=2 and for diseases with prevalence ranging from 0.1 to 1%, P(sporadic) will range from 66 to 99% (definition I) or from 52 to 99% (definition II), with hL2 from 100 to 0%. Therefore, for these diseases, the proband cases observed in typical families will more likely seem to be sporadic no matter how heritable the disease is. By contrast, a large proportion of probands would present with a family history for a disease with a high prevalence (K=0.1); even if the heritability is extremely low (hL2=10%), there are 31% (definition I) or 65% (definition II) of probands having a family history. In addition, the nth-degree RR can be calculated analytically as

with i=z/K; and z is the height of the standard normal curve at the truncation point T (Appendix). For example, when S=2 and for diseases with prevalence ranging from 0.1 to 1%, P(sporadic) will range from 66 to 99% (definition I) or from 52 to 99% (definition II), with hL2 from 100 to 0%. Therefore, for these diseases, the proband cases observed in typical families will more likely seem to be sporadic no matter how heritable the disease is. By contrast, a large proportion of probands would present with a family history for a disease with a high prevalence (K=0.1); even if the heritability is extremely low (hL2=10%), there are 31% (definition I) or 65% (definition II) of probands having a family history. In addition, the nth-degree RR can be calculated analytically as  (Appendix). The RRs for relatives from this equation were verified by simulations and are listed in Table 1. In line with the results for P(sporadic), RRs largely depended on disease prevalence K. Although the relationship of hL2, K and λn is theoretically nonlinear, the relationship between log(λ1) and −hL2 log(K) is approximately linear for each K (Figure 3), and is roughly log(λ1)=−0.62 hL2 log(K) with regression R2=99.4% for K from 0.01 to 10%.

(Appendix). The RRs for relatives from this equation were verified by simulations and are listed in Table 1. In line with the results for P(sporadic), RRs largely depended on disease prevalence K. Although the relationship of hL2, K and λn is theoretically nonlinear, the relationship between log(λ1) and −hL2 log(K) is approximately linear for each K (Figure 3), and is roughly log(λ1)=−0.62 hL2 log(K) with regression R2=99.4% for K from 0.01 to 10%.

An analytical method to calculate hL2 using K and λ1 is provided in the Appendix. We used this method to predict heritability of liability for a range of common complex diseases using the observable parameters, namely, disease prevalence and first-degree RR (Table 2). Given hL2 and K of disease, we also predicted P(sporadic) from our analytical approximation and checked all our analytic results by simulation. The predictions of P(sporadic) for these diseases are presented in Table 2. The predictions of P(sporadic) from simulation agreed well with those from approximation, with a correlation of 0.998.

Discussion

Using the relationship between underlying and observed scale parameters under a polygenic inheritance model, we predicted hL2 for a list of human complex diseases, using K and λ1 collected from literature. The proportion of sporadic cases and RRs for relatives depends mainly on disease prevalence. If we consider three-generation pedigrees with S=2, then for diseases with a low prevalence (K<1%), even if they are highly heritable (hL2=90%), the disease cases will seem more likely to be sporadic, P(sporadic II) >63% (Figure 2b). On the other hand, for a disease with a high prevalence (K >10%), a large proportion of disease cases seems to have a family history, P(sporadic II) <37% (Figure 2b), even when disease heritability is extremely low (hL2=10%). Kendler15 modeled familial versus sporadic schizophrenia and major depression using simple genetic and environment etiology models. He showed that family history had a high positive predictive value, but a low negative predictive value. Under the liability threshold model, these results still apply, that is, a positive family history implies a high genetic liability to disease and a negative family history implies very little about genetic liability to disease.

Our results necessarily reflect our assumptions in modeling complex genetic disease. First, we assumed that the causes of familiality of complex disease reflect only genetic rather than family environment factors. As more distant relatives are less likely to share the same environmental risk factors, this assumption can be tested by comparing RRs for different types of relatives with their expected values under a genetic etiology model. Second, we used idealized family history assuming that the true disease status of all relatives is known, ignoring recall errors and age of onset factors. This implies that our estimates of proportion of sporadic cases are conservative and in practice may be even higher than our prediction. Moreover, in some diseases, family history reflects increased severity of the disease,16 which, although not inconsistent with a polygenic model, may imply genetic heterogeneity. Finally, we assumed that a liability threshold model is representative of complex genetic diseases. The model assumes a normally distributed liability to disease, with disease occurring in those who exceed a liability threshold. A normal distribution of liability would be achieved if there are multiple genetic and environmental factors, each making a small contribution to the risk of disease. Comparison of the prediction frequency of familial versus sporadic cases provides some benchmark for the validity of our assumptions. For example, a Swedish population study investigated breast cancer in 1 732 775 sisters from 763 963 families (S=2.3) before the age of 70 years.17 A total of 16 505 proband cases and 714 sisters of probands were identified with breast cancer, which provides the estimates of K=1% and λs=3 for breast cancer before the age of 70 years. We predicted an hL2 of 35% by our analytical equation. Given K and hL2, we simulated 1 million nuclear families with S=2.3, and estimated a multiplex proportion of siblings (the number of families with at least two affected siblings divided by the number with at least one sibling) of 4.6%, with 95% CI of 4.2% ∼5.0%, which is consistent with the observed proportion of 4.3%.

We consider the example of schizophrenia. The prevalence of sporadic versus familial cases has been considered in detail under a range of genetic models15, 18 in the context of etiological heterogeneity of schizophrenia. The latest evidence from GWAS for schizophrenia points to a large polygenic component.19 At the same time, significantly increased rates of de novo copy number variant (CNV) mutations have been reported in sporadic (but not familial) cases of schizophrenia,20 together implying genetic heterogeneity. In combination, these results point to many risk alleles that have a range of frequencies and effect sizes but that are still consistent with a normally distributed underlying liability to disease. Genetic epidemiology parameters of schizophrenia are classically quoted to be K=1%, λ1=8.6 and hL2=81%,21 but results from a Swedish population sample of >9 million have revised these estimates to K=0.4%, λ1=9 and hL2=64%.22, 23 For K=0.4% and λ1=9, we predict hL2 to be 63%, and for K=1% and λ1=8.6, we predict hL2 to be 80%, reflecting that under a threshold liability model, the lower disease prevalence forces a lower estimate of hL2 for the same λ1. For K=0.4% and hL2=63%, we predict the proportion of sporadic schizophrenia cases to be 90% (definition I) and 83% (definition II) in three-generation pedigrees with S=2 (Table 2). The Swedish population study observed a multiplex proportion of 3.8% (the number of families with at least two affected members divided by the number with at least one affected member)17 from nuclear families with ∼3.8 members per family.16 We simulated 1 million nuclear families with S=1.8, and estimated the multiplex proportion as 4.0% (95% CI of 3.7–4.4% from 100 simulation replicates) and P(sporadic I) as 90.6% (95% CI of 89.7–91.5%).

In conclusion, although sporadic cases can arise from nongenetic risk factors and from new mutations with large effects, a large proportion of sporadic cases is expected under the polygenic model, a result that reflects the relatively low prevalence rates (<5%) that are typical of common complex genetic diseases. Therefore, it is not possible to make any inference with regard to the causal mechanism of a complex disease from the observed proportion of sporadic cases alone.

References

WTCCC: Genome-wide association study of 14 000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature 2007; 447: 661–678.

Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD et al: Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 857–864.

Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 638–645.

Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ et al: Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 830–832.

Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD et al: Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 596–604.

Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M et al: Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 310–315.

Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG et al: Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 316–321.

Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM et al: Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature 2007; 447: 1087–1093.

Fisher RA : The correlation between relatives on the supposition of Mendelian inheritance. Trans R Soc Edinb 1918; 52: 399–433.

Gottesman II, Shields J : A polygenic theory of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1967; 58: 199–205.

Falconer DS, Mackay TFC : Introduction to quantitative genetics. England: Longman, 1996.

Pharoah PDP, Antoniou A, Bobrow M, Zimmern RL, Easton DF, Ponder BAJ : Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat Genet 2002; 31: 33–36.

Dempster ER, Lerner IM : Heritability of threshold characters. Genetics 1950; 35: 212–236.

Cui J, Hopper JL : Why are the majority of hereditary cases of early-onset breast cancer sporadic? A simulation study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000; 9: 805–812.

Kendler KS : Sporadic vs familial classification given etiologic heterogeneity: I. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value. Genet Epidemiol 1987; 4: 313–330.

Harney S, Wordsworth BP : Genetic epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Tissue Antigens 2002; 60: 465–473.

Rebora P, Czene K, Reilly M : Timing of familial breast cancer in sisters. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008; 100: 721–727.

Eaves LJ, Kendler KS, Schulz II SC : The familial sporadic classification: its power for the resolution of genetic and environmental etiologic factors. J Psychiatr Res 1986; 20: 115–130.

The International Schizophrenia Consortium: Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 2009; 460: 748–752.

Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, van Rensburg EJ, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M : Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 880–885.

Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC : Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: 1187–1192.

Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Bjork C et al: Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet 2009; 373: 234–239.

Lichtenstein P, Bjork C, Hultman CM, Scolnick E, Sklar P, Sullivan PF : Recurrence risks for schizophrenia in a Swedish national cohort. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 1417–1425.

Lynch M, Walsh B : Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 1998.

James JW : Frequency in relatives for an all-or-none trait. Ann Hum Genet 1971; 35: 47–49.

Reich T, James JW, Morris CA : The use of multiple thresholds in determining the mode of transmission of semi-continuous traits. Ann Hum Genet 1972; 36: 163–184.

Risch N : The genetic epidemiology of cancer: interpreting family and twin studies and their implications for molecular genetic approaches. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001; 10: 733–741.

Risch N : Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. I. Multilocus models. Am J Hum Genet 1990; 46: 222–228.

McGue M, Gottesman II, Rao DC : The transmission of schizophrenia under a multifactorial threshold model. Am J of Hum Genet 1983; 35: 1161–1178.

Craddock N, Khodel V, Van Eerdewegh P, Reich T : Mathematical limits of multilocus models: the genetic transmission of bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 57: 690–702.

Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF : Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 1097–1106.

Hyttinen V, Kaprio J, Kinnunen L, Koskenvuo M, Tuomilehto J : Genetic liability of type 1 diabetes and the onset age among 22 650 young Finnish twin pairs: a nationwide follow-up study. Diabetes 2003; 52: 1052–1055.

Das SK, Elbein SC : The genetic basis of type 2 diabetes. Cellscience 2006; 2: 100–131.

Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist K, Sundquist J : Familial risks for asthma among twins and other siblings based on hospitalizations in Sweden. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37: 1320–1325.

Marenberg ME, Risch N, Berkman LF, Floderus B, Defaire U : Genetic susceptibility to death from coronary heart disease in a study of twins. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1041–1046.

Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA et al: Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 204–210.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mike Goddard and Shaun Purcell for helpful comments on the paper. This study was supported by the Australian National and Medical Research Council (Grants 389892, 442915, 339450, 443011 and 496688) and by the Australian Research Council (Grant DP0770096).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix Relationship of additive genetic effects between parents and offspring under a polygenic model

Following Lynch and Walsh,24 under the assumption of a polygenic inheritance for a quantitative trait, the additive genetic effect of a parent (ap) and its gamete (ag) is

where xi is coded as 0, 1 or 2 if the genotype at locus i is qq, Qq or QQ (alleles are arbitrarily called Q or q); zi is coded as 0 or 1 if the genotype of locus i is q or Q; and bi is the allelic effect at locus i.

Although the parent passes half of the genome to its gamete, ag is not necessarily equal to ½ap because of random segregation of alleles.

Assuming that all of the loci are independent, the additive genetic variance equals

where pi is the frequency of allele Q at locus i.

As

Therefore, we can express the additive effect of a gamete as

Consequently, we can express the additive effect of offspring as

where aF and aM are the additive effects of two parents, m is the effect due to Mendelian segregation,

Relationship between underlying and observed scales under a threshold liability model

Consider a disease on the basis of a threshold liability model with population prevalence K. The liability of the nth-degree relatives of the proband case follows the normal distribution of Falconer and Mackay11

where hL2 is the heritability of liability and z is the height of the standard normal curve at the truncation point T pertaining to a disease prevalence of K.

Given a proband case, the probability of the nth-degree relative being is

where  is standard normal cumulative distribution function and

is standard normal cumulative distribution function and

Therefore, the nth-degree RR is  , which provides a link between the underlying liability scale and the observed risk scale. In particular, the RR to MZ twin is

, which provides a link between the underlying liability scale and the observed risk scale. In particular, the RR to MZ twin is  Following James,25 the nth-degree RR can also be expressed as

Following James,25 the nth-degree RR can also be expressed as  where

where  is the covariance between the proband case and its nth-degree relatives on the observed 0–1 scale, hence

is the covariance between the proband case and its nth-degree relatives on the observed 0–1 scale, hence  Therefore, the heritability on the observed 0–1 scale is

Therefore, the heritability on the observed 0–1 scale is

In addition, if there are fn number of nth-degree relatives, the probability of a proband case without family history is approximately

This approximation is a conservative prediction of P(sporadic) because the probabilities of affected relatives are not independent, especially when both K and hL2 are high and lots of relatives are included.

All the derivations above begin with K and hL2 being known parameters; in practice, however, only λn and K are observable. Given λ1 and K, hL2 can be predicted by rearranging Eq. A1 for n =1 and solving for hL2.24, 26

where T1 is truncation point pertaining to the accumulative probability

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Visscher, P. & Wray, N. Sporadic cases are the norm for complex disease. Eur J Hum Genet 18, 1039–1043 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2009.177

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2009.177

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in polygenic scores: translation, equitability, methods and FAIR tools

Genome Medicine (2024)

-

Development and multi-site external validation of a generalizable risk prediction model for bipolar disorder

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

Bipolar multiplex families have an increased burden of common risk variants for psychiatric disorders

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)

-

The genomics of major psychiatric disorders in a large pedigree from Northern Sweden

Translational Psychiatry (2019)

-

Advanced paternal age effects in neurodevelopmental disorders—review of potential underlying mechanisms

Translational Psychiatry (2017)