Abstract

The detection of silica-rich dust particles, as an indication for ongoing hydrothermal activity, and the presence of water and organic molecules in the plume of Enceladus, have made Saturn’s icy moon a hot spot in the search for potential extraterrestrial life. Methanogenic archaea are among the organisms that could potentially thrive under the predicted conditions on Enceladus, considering that both molecular hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) have been detected in the plume. Here we show that a methanogenic archaeon, Methanothermococcus okinawensis, can produce CH4 under physicochemical conditions extrapolated for Enceladus. Up to 72% carbon dioxide to CH4 conversion is reached at 50 bar in the presence of potential inhibitors. Furthermore, kinetic and thermodynamic computations of low-temperature serpentinization indicate that there may be sufficient H2 gas production to serve as a substrate for CH4 production on Enceladus. We conclude that some of the CH4 detected in the plume of Enceladus might, in principle, be produced by methanogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus emits jets of mainly water (H2O) from its south-polar region1. Besides H2O, the ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) onboard NASA’s Cassini probe detected methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), ammonia (NH3), molecular nitrogen (N2), and molecular hydrogen (H2) in the plume2. In addition, carbon monoxide (CO) and ethene (C2H4) were found among other substances with moderate ambiguity3,4,5,6 (Table 1). At 1608.3 ± 4.5 kg m[−31, Enceladus possesses a relatively high-bulk density for an icy moon, which leads to the assumption that a substantial part of its core consists of chondritic rocks7. At the boundary between the liquid water layer and the rocky core, geochemical interactions are assumed to occur at low to moderate temperatures (<100 °C)2,7,8. The most prominent potential source of H2 in Enceladus’ interior may be oxidation of native and ferrous iron in the course of serpentinization of olivine in the chondritic core. Olivine hydrolysis at low temperatures is a key process for sustaining chemolithoautotrophic life on Earth9 and if H2 is produced in significant amounts on Enceladus, then it could also serve as a substrate for biological CH4 production. Considering that 139 ± 28 × 109 to 160 ± 43 × 109 kg carbon year−1 of the CH4 found in the atmosphere of Earth is emitted from natural sources10, including biological methanogenesis, the question was raised if CH4 detected in the plume of Enceladus could in principle also originate from biological activity11.

To date, methanogenic archaea are the only known microorganisms that are capable of performing biological CH4 production in the absence of oxygen12,13. On Earth, methanogens are found in a wide range of pH (4.5–10.2), temperatures (<0–122 °C), and pressures (0.005–759 bar)13 that overlap with conditions predicted in Enceladus’ subsurface ocean, i.e., temperatures between 0 and above 90 °C8, pressures of 40–100 bar8, a pH between 8.5–10.58 and 10.8–13.514, and a salinity in the range of our oceans. While autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogens might metabolise some of the compounds found in Enceladus’ plume, other compounds which were detected in the plume with different levels of ambiguity, such as formaldehyde (CH2O), methanol (CH3OH), NH3, CO, and C2H4 are known to inhibit growth of methanogens on Earth at certain concentrations15,16,17.

Here we show that methanogens can produce CH4 under Enceladus-like conditions, and that the estimated H2 production rates on this icy moon can potentially be high enough to support autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenic life.

Results

Effect of gaseous inhibitors on methanogens

To investigate growth of methanogens under Enceladus-like conditions, three thermophilic and methanogenic strains, Methanothermococcus okinawensis (65 °C)18, Methanothermobacter marburgensis (65 °C)19, and Methanococcus villosus (80 °C)20, all able to fix carbon and gain energy through the reduction of CO2 with H2 to form CH4, were investigated regarding growth and biological CH4 production under different headspace gas compositions (Table 2) on H2/CO2, H2/CO, H2, Mix 1 (H2, CO2, CO, CH4, and N2) and Mix 2 (H2, CO2, CO, CH4, N2, and C2H4). These methanogens were prioritised due to their ability to grow (1) in a temperature range characteristic for the vicinity of hydrothermal vents21, (2) in a chemically defined medium22, and (3) at low partial pressures of H223. Also, in the case of M. okinawensis, the location of isolation was taken into consideration, since the organism was isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent field at Iheya Ridge in the Okinawa Trough, Japan, at a depth of 972 m below sea level18, suggesting a tolerance toward high pressure.

While M. okinawensis, M. marburgensis, and M. villosus all showed growth on H2/CO2 to similar optical densities, no growth of M. marburgensis could be observed when C2H4 (Mix 2) was supplied in the headspace (Fig. 1). Growth of both M. villosus and M. okinawensis was observed even when CO and C2H4 were both present in the headspace gas. However, while M. villosus showed prolonged lag phases and irregular growth under certain conditions, M. okinawensis grew stably and reproducibly on the different gas mixtures without extended lag phases (Fig. 1). As expected, the final optical densities did not reach those of the experiments with H2/CO2, likely because in Mix 1 and Mix 2 lower absolute amounts of convertible gaseous substrate (H2/CO2) were available compared to the growth under pure H2/CO2. Consequently, growth kinetics showed a different, gas-limited linear inclination in the closed batch setup when using Mix 1 and Mix 222,24. Due to its reproducible growth, M. okinawensis was chosen for more extensive studies on biological CH4 production under putative Enceladus-like conditions.

Influence of the different headspace gas compositions on growth of M. marburgensis, M. villosus, and M. okinawensis. The error bars show standard deviations calculated from triplicates. OD curves of a, d, g, j, m M. marburgensis, b, e, h, k, n M. villosus and c, f, i, l, o M. marburgensis for a–c H2/CO2, d–f H2/CO, g–i H2, j–l Mix 1, and m–o Mix 2. Growth of M. marburgensis was inhibited by the presence of C2H4 (see Table 2 for detailed gas composition). Only M. marburgensis seemed to be able to use sodium hydrogen carbonate (supplied in the medium) as C-source in case of a lack of CO2 (H2 or H2/CO as sole gas in the headspace). Both, M. villosus and M. okinawensis showed growth when Mix 1 and Mix 2 were applied to the serum bottle headspace; however, M. villosus exhibited extended lag phases. The dips in the graphs b, c were caused by substrate limitation due to depletion of serum bottle headspace of H2/CO2 at high-optical cell densities

M. okinawensis tolerates Enceladus-like conditions at 2 bar

Growth and turnover rates (calculated via the decrease in headspace pressure) of M. okinawensis cultures were determined in the presence of selected putative liquid inhibitors detected in Enceladus’ plume (NH3, given as NH4Cl, CH2O, and CH3OH). While growth of M. okinawensis could still be observed at the highest concentration of NH4Cl added to the medium (16.25 g L−1 or 0.30 mol L−1), the organism grew only in the presence of up to 0.28 mL L−1 (0.01 mol L−1) CH2O. This is less than, but importantly still in the same order of magnitude of, the observed maximum value of 0.343 mL L−1 CH2O detected in the plume25. Growth and CH4 production of M. okinawensis in closed batch cultivation was shown at CH3OH and NH4Cl concentrations exceeding those reported for Enceladus’ plume4,5,25,26.

To explore how the presence of these inhibitors might influence growth and turnover rates of M. okinawensis, we have applied these compounds at various concentrations in a multivariate design space setting (Design of Experiment (DoE)). At different concentrations of CH2O, CH3OH, and NH4Cl, M. okinawensis cultures showed growth (Fig. 2) and turnover rates from 0.015 ± 0.012 to 0.084 ± 0.018 h−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1; experiments L and K in Fig. 2). CH3OH amendments at concentrations between 9.09 and 210.91 µL L−1 (0.22–5.21 mmol L−1) did not reduce or improve growth of M. okinawensis (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Compared to the highest applied CH2O concentration, the turnover rate of M. okinawensis was ~5.6-fold higher at the lowest tested concentration. The results of this experiment indicated that M. okinawensis possessed a physiological tolerance towards a broad multivariate concentration range of CH2O, CH3OH, and NH4Cl and was able to perform the autocatalytic conversion of H2/CO2 to CH4 while gaining energy for growth.

Schematic of the experimental setting and DoE raw data growth curves showing OD measurements. The DoE is based on a central composite design (figure in the upper left corner). NH4Cl, CH2O, and CH3OH were used as factors during the experiment and systematically varied in a multivariate design space (see Supplementary Table 1 for the concrete values). Each of the factors setting was examined in triplicates. The centre point (O) was examined in quintuplicates. The colours of the dots and the letters of the figure in the upper left corner correspond to the growth curves. The line labelled ZC represents the optical density of a corresponding zero control experiment, which was done with the same medium as the experiments labelled with O (central point), but without inoculum. The different colours represent different performances. For better readability, the error bars in this diagram were excluded, which were in a standard deviation range between 0.0009 and 0.1544. According to statistical selection criteria three experiments (one experiment F and two experiments O) were excluded from ANOVA analysis (Supplementary Table 2)

We used the mean liquid inhibitor concentrations for CH2O determined in the DoE experiment (DoE centre points) and Enceladus-like concentrations for CH3OH and NH4Cl (Supplementary Table 3) to test growth and turnover rates of M. okinawensis, using different gases in the headspace (H2/CO2, Mix 1, and Mix 2 (Fig. 3)). Under all tested headspace gas compositions, M. okinawensis showed gas-limited growth (max. OD values of 0.67 ± 0.02, 0.17 ± 0.03, and 0.13 ± 0.03 after ~237 h for H2/CO2, Mix 1 and Mix 2, respectively). The calculated turnover rates correlated with the different convertible amounts of H2/CO2 in Mix 1 and Mix 2. Hence, M. okinawensis was able to grow and to convert H2/CO2 to CH4 when CH2O, CH3OH, NH4Cl, CO and C2H4 were present in the growth medium at the concentrations calculated from Cassini’s INMS data (assuming 1 bar, compare Tables 1 and 2). The mixing ratios of these putative inhibitors were based on INMS data4,5,25,26 but higher than those calculated by using the most recent Cassini data2,6 (Table 1). This demonstrates that growth and biological CH4 production of M. okinawensis is possible even at higher inhibitor concentrations.

Growth and turnover rate of M. okinawensis under Enceladus-like conditions at 2 bar. a, c, e Growth curves (OD578 nm) and b, d, f turnover rates (h−1) as a measure of CH4 production of M. okinawensis on a, b H2/CO2 (4:1), c, d Mix 1 and e, f Mix 2. For detailed composition of gases and media see Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. I and II (light and dark colours, respectively) denote two independent experiments (each performed in triplicates, error bars = standard deviation). Enceladus-like concentrations were used for NH4Cl and CH3OH and mean liquid inhibitor concentrations determined in the DoE were used for CH2O. The dip in a was caused by substrate limitation due to depletion of serum bottle headspace of H2/CO2 at high-optical cell densities

M. okinawensis tolerates Enceladus-like conditions up to 50 bar

Due to the fact that methanogens on Enceladus would possibly need to grow at hydrostatic pressures up to 80 bar8 and beyond, the effect of high pressure on the conversion of headspace gas for M. okinawensis was examined in a pressure-resistant closed batch bioreactor. Headspace H2/CO2 conversion and CH4 production was examined at 10, 20, 50, and 90 bar, either using H2/CO2 in a 4:1 ratio or applying H2/CO2/N2 in a 4:1:5 ratio. A gas conversion of >88% was shown for each of the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 2) except for the 90 bar experiment using H2/CO2/N2, where the headspace gas conversion was found to be at 66.4%. However, no headspace gas conversion and CH4 production could be detected when cultivating M. okinawensis at 90 bar using H2/CO2 only (data not shown).

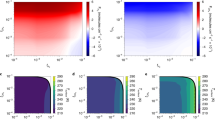

Final experiments were designed to investigate headspace H2/CO2 conversion and CH4 production of M. okinawensis according to INMS data (Table 3) and under conditions of high pressure (10.7 ± 0.1, 25.0 ± 0.7, and 50.4 ± 1.7 bar). Turnover rate, methane evolution rate (MER, calculated via pressure drop) and biological CH4 production (calculated via gas chromatography measurements) for these experiments are shown in Fig. 4. When simultaneously applying putative gaseous (Table 4) and liquid inhibitors (Supplementary Table 3) under high-pressure conditions, we reproducibly demonstrated that M. okinawensis was able to perform H2/CO2 conversion and CH4 production under Enceladus-like conditions.

CH4 production, MER, and turnover rate of M. okinawensis under Enceladus-like conditions at high pressure. Biological CH4 production determined by gas chromatography (blue) (Vol.-% h−1) and turnover rates (h−1) (green) and MER·10 (mmol L−1 h−1) (red) measured from headspace gas conversion using M. okinawensis (experiment 1 in light colours, experiment 2 in dark colours) under putative Enceladus-like conditions in a 2.0 L bioreactor (for detailed medium composition, see Supplementary Table 3 and for detailed gas composition see Table 4, n = 2). The positive control experiment contained also the liquid inhibitors but only H2/CO2 (4:1) in the headspace. For high-pressure experiments without any inhibitors see Supplementary Fig. 2

Methanogenic life could be fuelled by H2 from serpentinization

In light of these experimental findings and the presence of H2 in Enceladus’ plume2, the question arose if serpentinization reactions can support a rate of H2 production that is high enough to sustain autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenic life. To address this question, we used the PHREEQC27 code to model serpentinization-based H2 production rates under Enceladus-like conditions (Table 5) with the assumption that the rate-limiting step of the serpentinization reaction is the dissolution of olivine. H2 production rates are poorly constrained, as they strongly depend on assumed grain size and temperature. These rates correspond to the low end of the range of H2 production rates, which were based on a thermal cooling and cracking model28. Of the many reactions involved in serpentinization of peridotite, dissolution of the Fe(II)-bearing primary phases is a critical one29, and the only one for which kinetic data are available. In the model, CO2 reduction to CH4 is predicted to take place once enough H2 in the system was produced to generate thermodynamic drive for the reaction. While abiotic CH4 production is kinetically more sluggish than olivine dissolution30, biological CH4 production is fast and may be controlled by the rate at which H2 is supplied. The abiotic CH4 production rates listed in Table 5 are hence also modelled such that olivine dissolution is the rate-limiting step. The results of these thermodynamic and kinetic computations show that H2 and CH4 production is predicted for a range of rock compositions (Table 5) and temperature conditions (Supplementary Table 4). The model system essentially represents a closed system with high-rock porosity, such as proposed for Enceladus2. The computational results predict how much H2 and CH4 should form within the intergranular space inside Enceladus’ silicate core with water-to-rock-ratios between 0.09 and 0.12 (Table 5). The serpentinization reactions are predicted to produce solutions with circumneutral to high pH between 7.3 and 11.3, as well as amounts of H2 that greatly exceed the amount of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) trapped in the pore space. As the computations indicate that there is ample thermodynamic drive for reducing DIC to CH4, these results corroborate the idea that serpentinization reactions on Enceladus might fuel autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenic life. However, we would like to point out that if methanogenic life were indeed active on Enceladus, biological CH4 production would always compete with abiotic CH4 generation processes resulting in a mixed CH4 production.

Discussion

In this study, we show that the methanogenic strain M. okinawensis is able to propagate and/or to produce CH4 under putative Enceladus-like conditions. M. okinawensis was cultivated under high-pressure (up to 50 bar) conditions in defined growth medium and gas phase, including several potential inhibitors that were detected in Enceladus’ plume2,4,6. The only difference between the growth conditions of M. okinawensis and the putative Enceladus-like conditions was the lower pH value applied during the high-pressure experiments. Due to the supply of CO2 at high-pressure in the experiments the pH decreased to ~5, while pH values between 7.3 and 13.5 were estimated for Enceladus’ subsurface ocean (this study and refs. 8,14).

Another point of debate might be the cultivation temperatures used for the thermophilic and hyperthermophilic methanogens in this study. The mean temperature in the subsurface ocean of Enceladus might be just above 0 °C except for the areas where hydrothermal activity is assumed to occur. In these hydrothermal settings temperatures higher than 90 °C are supposedly possible8, and are therefore the most likely sites for higher biological activity on Enceladus. Although methanogens are found over a wide temperature range on Earth, including temperatures around 0 °C31, growth of these organisms at low temperatures is observed to be slow13.

We estimated H2 production rates between 4.03 and 50.7 nmol g−1 L−1 d−1 in the course of serpentinization on Enceladus (Table 5). These estimates are rather conservative, as they are based on the assumption of small specific mineral surface areas. In a recent study, the rate of serpentinization has been estimated from a physical model that predicts how fast cracking fronts propagate down into Enceladus’ core28. Combining this physically controlled advancement of serpentinization (8 × 1011 g y[−128) with our estimates for kinetically limited rates of H2 production leads to overall rates of 3–40 × 104 mol H2 y−1 for Enceladus. Although still high enough to support biological methanogenesis, these rates are orders of magnitude lower than the previously suggested 10 × 108 mol H2 y[−128 assuming that the speed of cracking front propagation controls the rate of H2 production. We hence suggest that reaction kinetics may play an important role in determining the overall H2 production rate on Enceladus. Our computed steady-state H2 production rates are lower than the 1–5 × 109 mol H2 y−1 estimated from Cassini data2. This apparent discrepancy in flux rates can be reconciled if the Enceladus plume was a transient (i.e., non-steady state) phenomenon. The predicted H2/CH4 ratio of 2.5 (Fo90:En:Diop = 8:1:1) to 4 (Fo90) for the magnesian compositions of Enceladus’ core (Table 5) are consistent with the relative proportions of the two gases in the plume (0.4–1.4% H2, 0.1–0.3% CH4)2.

Based on our estimated H2 production rate, we can calculate how much of the available DIC on Enceladus could be fixed into biomass through autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. If we assume a typical elementary composition of methanogen biomass32, 7.13 g carbon could be fixed per g hydrogen fixed. Under optimal growth conditions, ~3%22,23 of the available carbon can be assimilated into biomass, and assuming that methanogens possess a molecular weight of ~30.97 g C-mol[−122 and that the total amount of H2 produced would be available for the carbon and energy metabolism of autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogens, a biomass production rate between 20 and 257 C-nmol g−1 L−1 y−1 could be achieved. In another approach, we can use the actually predicted CH4 production rates of 1.32–2.05 nmol g−1 L−1 d−1 (Table 5) and a Gibbs energy dissipation approach in which we assume that 10% of the energy of CH4 production is fuelling biosynthesis28. This yields similar numbers of biomass production rate, i.e., 28 and 56 C-nmol g−1 L−1 y−1.

Based on our findings, it might be interesting to search for methanogenic biosignatures on icy moons in future space missions. Methanogens produce distinct and lasting biosignatures, in particular lipid biomarkers like ether lipids and isoprenoid hydrocarbons. Other potential biomarkers for methanogens are high-nickel (Ni) concentrations (and its stable isotopes33), as Ni is e.g., part of methyl-coenzyme M reductase, the key enzyme of biological methanogenesis23. However, both lipid biomarkers and Ni-based biosignatures are likely only to be identifiable at the site of biological methanogenesis, and the effect of dilution with increasing distance away from the methanogen habitat is likely to prevent their use as a general marker for biological methanogenesis in Enceladus’ plume or in a subsurface ocean. If, however, bubble scrubbing would occur, a process by which organic compounds and cells adhere to bubble surfaces and are carried away as bubbles rise, which was suggested to occur on Enceladus34, the amount of bioorganic molecules and cells would be much higher and future lander missions could easily collect physical evidence for the presence of autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenic life on Enceladus.

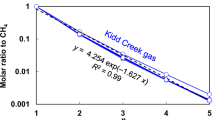

Additionally, one could consider using stable isotopes of CH4 and CO2 and ratios of low-molecular weight hydrocarbons to evaluate the possibility of biological methanogenesis on Enceladus11. But given the uncertainties on the geological and hydrogeological boundary conditions that influence the targeted isotope and molecular patterns in Enceladus’ plume, such an approach is not trivial. In contrast to biological and thermogenic CH4 production, the latter resulting from the decomposition of organic matter, abiogenic CH4 is believed to be produced by metal-catalysed Fischer–Tropsch or Sabatier type reactions under hydrothermal conditions and particularly in the course of serpentinization of ultramafic rocks35. Although biologically produced CH4 is usually characterised by its strong 13C depletion, growth of methanogens at high-hydrostatic pressures and high temperatures, which is typical of deep-sea hydrothermal systems, may significantly reduce kinetic isotope fractionation and result in relatively high δ13C values of CH4, hampering discrimination from non-microbial CH436. Given such uncertainties, multiply substituted, so-called ‘clumped’ isotopologues of CH4 emerge as new proxy to constrain its mode of formation and to recognise formation environments like serpentinization sites37.

Another approach to identify the origin of CH4 could be CH4/(ethane + propane) ratios, as low ratios are typical of settings dominated by thermogenic CH438. However, this ratio may fall short to unequivocally discriminate abiogenic from biologically produced CH4. For instance the ratio of CH4 concentration to the sum of C2+ hydrocarbon concentration (C1/C2+) in the serpentinite-hosted Lost City Hydrothermal Field of 950 ± 76 was found to be most similar to ratios obtained in experiments with Fischer–Tropsch type reactions (<100–>3000). Thermogenic reactions produce C1/C2+ ratios less than ~100, whereas biological methanogenesis results in ratios of 2000–1300039. More than 30 years of research on CH4 production have revealed that its biologic, thermogenic or abiogenic origin on Earth is often difficult to trace40. However, the experimental and modelling results presented in this study together with the estimates of the physicochemical conditions on Enceladus from earlier contributions make it worthwhile to increase efforts in the search for signatures for autotrophic, hydrogenotrophic methanogenic life on Enceladus and beyond.

Methods

Estimations of Enceladus’ interior structure

Due to its rather small radius, the uncompressed density of the satellite is almost equal to its bulk density, which makes a simplified model of Enceladus’ interior reasonable. Enceladus was divided into a rocky core (core density of 2300–2550 kg m−3), a liquid water layer (density of 960–1080 kg m−3), and an icy shell (ice density of 850–960 kg m−3) and hydrostatic equilibrium was assumed. Calculations of the hydrostatic pressure based on Enceladus mass of 1.0794 × 1020 kg41 and its mean radius of 252.1 km41 assuming a core radius of 190–200 km, an subsurface ocean depth of 60–10 km and a corresponding ice shell thickness of 2.1–52.1 km results in a pressure of ~44.3–25.2 bar or 80.1–56.2 bar (depending on the method, Supplementary Methods) at the water-core-boundary. For the high-pressure experiments in this study, including all inhibitors, three pressure values were chosen that lie in the range given by Hsu et al. (10–80 bar)8 and are related to our calculations, i.e., 10, 25, and 50 bar.

Low-pressure experiments

Growth and tolerance towards putative inhibitors of the three methanogenic strains Methanothermococcus okinawensis DSM 14208, Methanothermobacter marburgensis DSM 2133, and Methanococcus villosus DSM 22612 were elucidated (Fig. 1). All strains were obtained from the Deutsche Stammsammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany. Growth was resolved by optical density (OD) measurements (λ = 578 nm). H2/CO2–CH4 gas conversion [%], turnover rate [h−1] (see Equation (2) below), and MER were calculated from the decrease of the bottle headspace pressure and/or from measuring CH4 production in a closed batch setup22,24. The headspace pressures were measured using a digital manometer (LEO1-Ei, −1…3barrel, Keller, Jestetten, Germany) with filters (sterile syringe filters, w/0.2c μm cellulose, 514-0061, VWR International, Vienna, Austria), and cannulas (Gr 14, 0.60 × 30 mm, 23 G × 1 1/4”, RX129.1, Braun, Maria Enzersdorf, Austria). The detailed setting can be seen in Fig. 3(a) in Taubner and Rittmann22. All pressure values presented in this study are indicated as relative pressure in bar.

For the experiments at 2 bar regarding CO and C2H4 tolerance (see Figs. 1 and 3), the strains were incubated in the dark either in a water bath (M. marburgensis and M. okinawensis, 65 ± 1 °C) or in an air bath (M. villosus, 80 ± 1 °C). The methanogens were cultivated in 50 mL of their respective chemically defined growth medium. Compositions of the different growth media of the experiments shown in Figs. 1 and 3 can be found in Supplementary Tables 3 and 5–10. The final preparation of the medium in the anaerobic culture flasks was performed in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, USA). Experiments were performed over a time of 210–270 h. After each incubation period, serum bottle headspace pressure measurement (in order to be unbiased, flasks were previously cooled down to room temperature), OD-sampling, and gassing with designated gas or test gas was performed. OD measurement was performed at 578 nm in a spectrophotometer (DU800, Beckman Coulter, USA). A zero control was incubated together with each individual experiment and the OD of this control was subtracted from the measured OD from the inoculated flasks each time.

For hydrogenotrophic methanogens, which utilise H2 as electron donor for the reduction of CO2 to produce CH4 and H2O as their metabolic products, the following stoichiometric reaction equation was used12,23,24:

The turnover rate [h−1] correlates with the catalytic efficiency per unit of time, i.e., it is a way to indirectly quantify CH4 productivity. By assuming the above-mentioned chemical CO2 methanation stoichiometry and neglecting biomass formation, the turnover rate is an equivalent method for indirect quantification of CH4 production. It is defined as

where Δp [bar] is the difference in pressure before and after incubation, Δpmax [bar] is the maximal theoretical difference that would be feasible due to stoichiometric reasons22, and Δt [h] is the time period of incubation.

For the initial pressure experiments at 2 bar, the three methanogenic strains were tested under five different gas phase compositions (Table 2). A significant change in OD and turnover rate was observed between these experiments (as can be seen in Fig. 1). When Mix 1 and Mix 2 were applied, only a maximum of 22.66 ± 0.23 Vol.-% H2 (average, Table 2) could be converted to CH4 and biomass.

To evaluate the influences of the potential inhibitors NH3, CH2O, and CH3OH on the growth of M. okinawensis, several preliminary experiments were performed. For easier handling, NH3 was substituted by NH4Cl. Based on INMS data (Table 1) the amount of NH4Cl was calculated according to Henry’s law. For that, Henry’s law constant was calculated to be 0.1084 mol m−3 Pa−1 at 64 °C. This results in 11.6 g L−1 (0.22 mol L−1) NH4Cl to have ~1% of NH3 in the gaseous phase at equilibrium for the experiments under closed batch conditions. The influence of NH4Cl between 0.25 and 16.25 g L−1 (4.67 and 303.79 mmol L−1), CH2O between 0 to 111 µL L−1 (0–4.03 mmol L−1), and CH3OH between 0 and 200 µL L−1 (0–4.94 mmol L−1) was tested individually. CH2O (37 Vol.-%) and CH3OH (98 Vol.-%) were used as stock solutions.

To find an appropriate ratio for the final experiments, an experiment in a DoE setting was established. A central composite design with the parameters shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2 was chosen. The design space is spherical with a normalised radius equal to one. Experiments A–N were done in triplicates; experiments O were performed in quintuplicate. The results of these experiments in terms of OD can be seen in Fig. 2 and in terms of turnover rate in Supplementary Fig. 1. Each incubation time period was 10.0 ± 0.5 h. The ANOVA analysis of this study can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

The setting for the experiments under Enceladus-like conditions at 2 bar pressure included the medium described in Supplementary Table 3 and Mix 2 (Table 2) as gaseous phase. As can be seen in Fig. 3 there was a lag phase of two days, but after that continuous but slow growth was observed.

To calculate the molar concentration of H2 and CO2 in the medium (Table 3), Henry’s law was used:

where p X is the partial pressure of the respective gas and kH is Henry’s constant as a function of temperature:

where \({\mathrm{\Delta }}_{{\mathrm{soln}}}{\mathrm{H}}\) is the enthalpy change of the dissolution reaction. For \(k_{\mathrm H}^ \ominus\) the values 7.9 × 10−4 mol L−1 bar−1 and 3.4 × 10−2 mol L−1 bar−1 and for \(\frac{{ - {\mathrm{\Delta }}_{{\mathrm{soln}}}{\mathrm{H}}}}{R}\) the values 500 K and 2400 K for H2 and CO2, respectively, were used. This results in a Henry constant at 65 °C of 6.481 × 10−4 mol L−1 bar−1 and 1.329 × 10−2 mol L−1 bar−1 for H2 and CO2, respectively.

Another potential liquid inhibitor detected in Enceladus’ plume was hydrogen cyanide (HCN)3,4. However, calculations on HCN stability under the assumed conditions on Enceladus show that HCN would hydrolyse into formic acid and ammonia42. Further investigations on the stability of HCN at different pH values and temperatures yielded similar results43,44. It was therefore assumed that HCN might originate either from a very young pool, a recent aqueous melt, or from the icy matrix on Enceladus4,42. Due to this reasoning and the low probability of HCN presence in the subsurface ocean of Enceladus, HCN was neglected in all growth media used to perform the experiments.

High-pressure experiments

M. okinawensis initial high-pressure experiments were performed at its optimal growth temperature of 65 ± 1 °C using a chemically defined medium (250 mL, see Supplementary Table 10 for exact composition) and a fixed stirrer speed of 100 r.p.m. in a 0.7 L stirred stainless steel Büchi reactor. Before each of the experiments, the reactor was filled with medium and the entire setting was autoclaved under CO2 atmosphere to assure sterile conditions. Thereafter, the inoculum (1 Vol.-%), the NaHCO3, l-cysteine, Na2S·9 H2O (0.5 M) and trace element solution were transferred via a previously autoclaved transfer vessel into the reactor. Then the reactor was set under pressure with the selected gas mixture (added ~5 bar in discrete steps every 10 min). The initial high-pressure experiments were performed using both an H2/CO2 (4:1) gas phase and an H2/CO2/N2 (4:1:5) mixture. The reactor was equipped with an online pressure (ASIC Performer pressure sensor 0–400 bar, Parker Hannifin Corporation, USA) and temperature probe (thermo element PT100, −75 °C − 350 °C, TC Mess- und Regeltechnik GmbH, Mönchengladbach, Germany). The conversion was always above 88% except for the 90 bar experiment, wherein also N2 fixation into biomass could be assumed. Interestingly, the time until start of the conversion decreases for the H2/CO2 experiments upon an increase of headspace pressure in the initial setup. This could be an indication for a barophilic nature of this organism, but also due to the experimental closed batch setup.

Increasing pCO2 and associated pH change was determined using a pH probe (see Supplementary Fig. 3). This analysis showed that even a rather small pCO2 (2 bar) already decreases the pH from nearly neutral to >5 due to the medium composition, which is due to application of a medium with low-buffering capacity, also possibly occurring in Enceladus’ subsurface ocean. However, it remains an open question if the medium on Enceladus is buffered. This would lead to higher possible pCO245 without having a drastic influence on the reported pH. Furthermore, we calculated if NaHCO3 could be used as source of dissolved inorganic carbon and what would be the effect on the pH of the medium. Postberg et al. suggested a concentration of 0.02–0.1 mol kg−1 NaCO3 and 0.05–0.2 mol kg−1 NaCl in the medium to reach a pH level between 8.5 and 946. Calculations on the concentrations of dissolved CO2 in the high-pressure experiments were performed by using the mole fraction of dissolved CO2 in H2O depending on pCO2. The mole fractions for pCO2 of 0.7, 1.2, and 3.1 bar (as used in the experiments) at 65 °C were generated by extrapolation of given values in the region of pCO2 = 0–1 bar. H2/CO2 conversion and CH4 production could still be measured at 10 bar, 20 bar and 50 (i.e., pCO2 = 10) bar with H2/CO2 (4:1) gas phase, but no decrease in pressure was observed at 90 bar with H2/CO2 (4:1) gas phase (i.e., pCO2 = 18 bar) after >110 h (data not shown). It is assumed that no growth occurs under these conditions due to the high pCO2 (18 bar) and the associated decrease to a pH of <3, which is beyond the reported pH tolerance of M. okinawensis18.

The high-pressure experiments under Enceladus-like conditions were carried out in the presence of both gaseous and liquid inhibitors applying the optimal growth temperature of 65 ± 1 °C at individual pressures of 10, 25, and 50 bar in a stirred 2.0 L Büchi reactor at 250 r.p.m. The gas ratios of the final gas mixtures are reported in Table 4. The final liquid medium was the same as the one used in the final 2 bar experiments (incl. the liquid inhibitors, Supplementary Table 3). Due to the results from the pH experiments (Supplementary Fig. 3), the low pCO2 (~3 bar) was chosen to avoid a pH shift to more acidic values, which is not representative of Enceladus-like conditions. For final high-pressure experiments, the medium volume was set to 1.1 L and M. okinawensis H2/CO2 grown pre cultures of an OD = 34.4 and OD = 34.5 were used as inoculums (11 mL each). Preparation of the high OD M. okinawensis suspension was performed by collecting 1 L of serum bottle grown fresh culture (OD ~0.7), centrifuging the cells at 5346×g anaerobically for 20 min (Heraeus Multifuge 4KR Centrifuge, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Osterode, Germany), and re-suspending the cells in 20 mL of freshly reduced appropriate growth medium. The gases were added into the bioreactor headspace in the following order: CO, N2, CO2, H2, and C2H4 (5 bar every 10 min). During all high-pressure experiments OD measurements were not conducted because upon reactor depressurisation cell envelopes of M. okinawensis were found to be disrupted. To determine the amount of produced CH4 in the high-pressure experiments, gas samples were taken after reducing the pressure in the reactor down to 1.36 ± 0.25 bar. The sample was stored in 120 mL serum bottles and sealed with black septa (3.0 mm, Butyl/PTFE, La Pha Pack, Langerwehe, Germany). The volumetric concentrations of CH4 was determined using a gas chromatograph (7890 A GC System, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) equipped with a TCD detector and a 19808 ShinCarbon ST Micropacked Column (Restek GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany)22.

To determine the CH4 production [Vol.-% h−1] shown in Fig. 4, the value of CH4 Vol.-% was divided by the time of biological CH4 production in h. To exclude a potential lag phase, the starting point of biological CH4 production was set to the point in time when the decrease in pressure exceeded the initial pressure by 5% for 10 bar experiments or by 1% during the other experiments.

Serpentinization simulations

The PHREEQC27 code was used to simulate serpentinization reactions from 25 to 100 °C and from 25 to 50 bar in order to assess H2 production on Enceladus. The Amm.dat and llnl.dat databases were used for all simulations, which account for temperature and pressure dependent equilibrium constants for dissolved species and solid phases up to 100 °C and 1000 bar. Solution composition was taken from the chemical composition of erupting plume of Enceladus4, as the true chemistry of its subsurface sea is unknown. Dissolved concentrations of Ca2+, Fe2+, Mg2+, and SiO2 were assumed to be seawater-like and values from McCollom and Bach47 were used. At the very low water-to-rock ratios of our model, the compositions of the interacting fluids will be entirely rock buffered, so that the model results are insensitive to the choice of the starting fluid composition. DIC concentration was set to 0.04 mol L−1 taken from Glein et al.14, who estimated a possible range of 0.005–1.2 molal DIC in Enceladus’ subsurface ocean. The solid phase assemblage was composed of varying amounts of olivine, enstatite and diopside, as well as varying olivine compositions. Most planetary bodies exhibit olivine solid solutions (Mg, Fe)2SiO4 that are dominated by forsterite (Mg2SiO4). This has been shown for micrometeorites found on Earth, lunar meteorites, comets, and asteroids48,49,50,51. Stony iron meteorites, such as pallasites contain forsteritic olivine with up to 20% Fe2+ content52. Olivines in chondrites show a more varied compositions ranging between 7 and 70% ferrous iron53,54, to almost pure fayalite (Fe2SiO4)55. A realistic assumption is that olivines on Enceladus have a more forsteritic composition that resembles those of stony iron and lunar meteorites.

A composition of Fo90 was adopted for olivine. Calculations were limited to Fo90, fayalite, enstatite, and diopside, as experimental data on their dissolution kinetics at high pH and low temperature are available. Kinetic rate laws were applied for forsteritic olivine, fayalite, enstatite, and diopside from Wogelius and Walther56,57, Daval et al.58, Oelkers and Schott59, and Knauss et al.60, respectively. Dissolution rate laws for Fo90 and fayalite at 100 °C were extrapolated from rate data in Wogelius and Walther57 using the Arrhenius equation. Enstatite and diopside rate laws at 100 °C were power-law fitted from experimental data provided by Oelkers and Schott59 and Knauss et al.60, respectively. All rate laws are valid over a pH range from 2 to 12 at all temperatures. Kinetic rate laws were multiplied by the total surface area of each mineral present in solution in order to calculate moles of minerals dissolved per time. Surface areas of 590 cm2 g−1 for Fo90 and fayalite61, 800 cm2 g−1 for enstatite59, and 550 cm2 g−1 for diopside60 were used. These specific surface areas have been suggested to be typical for fine-grained terrestrial rocks. We adopted these numbers in our computations, as we have no constraints on what specific surface areas in Enceladus may be. If the core of Enceladus was similar to carbonaceous chondrite, then the average mineral grain size is smaller and hence the specific surface areas greater than we assumed62. We choose to use fairly small specific surface areas to provide conservative estimates for H2 production rates. Model 1 uses Fo90, enstatite and diopside in a ratio of 8:1:1, model 2 uses a pure Fo90 composition. The effect of ferrous iron content in olivine on H2 production rates was tested in computations where Fo50 (Fo:Fa 1:1, model 3) and Fo20 (Fo:Fa 2:8, model 4) were dissolved as the sole mineral. Fo50 and Fo20 were dissolved according to dissolution rates of Wogelius and Walther (their equation (6))57, and for temperatures beyond 25 °C dissolution rates for fayalite were extrapolated to 50 and 100 °C after Daval et al.58. Model 1 contained 40 mol of Fo90 and 5 mol of enstatite and diopside. For models 2–4, 55 mol of Fo90, Fo50, and Fo20 were used. Applying these amounts yield water-to-rock-ratios between 0.09 and 0.12 (Table 5).

The most likely environmental conditions present within Enceladus are temperatures between 25 and higher than 90 °C at 25–80 bar8, and temperatures of 50 °C and pressures of 50 bar were chosen for the four different models. In a separate set of computations, temperatures were altered to 25 and 100 °C, and pressures were set at 25 and 100 bar. These results are shown in Supplementary Table 4. As pressure has a negligible effect on H2 production, only the variations in temperature change are shown.

Data availability

The data sets analysed during the current study are available in this article and its Supplementary Information file, or from the corresponding author on request.

References

Porco, C. C. et al. Cassini observes the active south pole of Enceladus. Science 311, 1393–1401 (2006).

Waite, J. H. et al. Cassini finds molecular hydrogen in the Enceladus plume: evidence for hydrothermal processes. Science 356, 155–159 (2017).

Waite, J. H. et al. Cassini ion and neutral mass spectrometer: Enceladus plume composition and structure. Science 311, 1419–1422 (2006).

Waite, J. H. et al. Liquid water on Enceladus from observations of ammonia and 40Ar in the plume. Nature 460, 487–490 (2009).

Bouquet, A., Mousis, O., Waite, J. H. & Picaud, S. Possible evidence for a methane source in Enceladus’ ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1334–1339 (2015).

Magee, B. A. & Waite Jr, J. H. Neutral gas composition of Enceladus’ plume – model parameter insights from Cassini-INMS. In 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, abstr. 2974 (2017).

Sekine, Y. et al. High-temperature water-rock interactions and hydrothermal environments in the chondrite-like core of Enceladus. Nat. Commun. 6, 8604 (2015).

Hsu, H.-W. et al. Ongoing hydrothermal activities within Enceladus. Nature 519, 207–210 (2015).

Mayhew, L. E., Ellison, E. T., McCollom, T. M., Trainor, T. P. & Templeton, A. S. Hydrogen generation from low-temperature water-rock reactions. Nat. Geosci. 6, 478–484 (2013).

Tian, H. et al. The terrestrial biosphere as a net source of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Nature 531, 225–228 (2016).

McKay, C. P., Porco, C. C., Altheide, T., Davis, W. L. & Kral, T. A. The possible origin and persistence of life on Enceladus and detection of biomarkers in the plume. Astrobiology 8, 909–919 (2008).

Liu, Y. & Whitman, W. B. Metabolic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of the methanogenic archaea. in. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1125, 171–189 (2008).

Taubner, R.-S., Schleper, C., Firneis, M. G. & Rittmann, S. K.-M. R. Assessing the ecophysiology of methanogens in the context of recent astrobiological and planetological studies. Life 5, 1652–1686 (2015).

Glein, C. R., Baross, J. A. & Waite, J. H. The pH of Enceladus’ ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 162, 202–219 (2015).

Schink, B. Inhibition of methanogenesis by ethylene and other unsaturated hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 31, 63–68 (1985).

Kato, S., Sasaki, K., Watanabe, K., Yumoto, I. & Kamagata, Y. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of the thermophilic, aceticlastic methanogen methanosaeta thermophila responding to ammonia stress. Microbes Environ. 29, 162–167 (2014).

Daniels, L., Fuchs, G., Thauer, R. K. & Zeikus, J. G. Carbon monoxide oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 132, 118–126 (1977).

Takai, K., Inoue, A. & Horikoshi, K. Methanothermococcus okinawensis sp. nov., a thermophilic, methane-producing archaeon isolated from a western Pacific deep-sea hydrothermal vent system. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 1089–1095 (2002).

Schönheit, P., Moll, J. & Thauer, R. K. Growth parameters (Ks, μmax, Ys) of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Arch. Microbiol. 127, 59–65 (1980).

Bellack, A., Huber, H., Rachel, R., Wanner, G. & Wirth, R. Methanocaldococcus villosus sp. nov., a heavily flagellated archaeon that adheres to surfaces and forms cell–cell contacts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 1239–1245 (2011).

Martin, W., Baross, J., Kelley, D. & Russell, M. J. Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 805–814 (2008).

Taubner, R.-S. & Rittmann, S. K.-M. R. Method for indirect quantification of CH4 production via H2O production using hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Front. Microbiol. 7, 532 (2016).

Thauer, R. K., Kaster, A.-K., Seedorf, H., Buckel, W. & Hedderich, R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591 (2008).

Rittmann, S. K.-M. R., Seifert, A. & Herwig, C. Essential prerequisites for successful bioprocess development of biological CH4 production from CO2 and H2. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 35, 141–151 (2015).

Waite, J. H. et al. Enceladus plume composition. In EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011 (2011).

Perry, M. E. et al. Inside Enceladus' plumes: the view from Cassini’s mass spectrometer. In American Astronomical Society, DPS Meeting 47, abstr. 410.04 (2015).

Parkhurst, D. L. & Appelo, C. A. J. User’s Guide to PHREEQC (Version 2): A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations. Water-Resources Investigations Report 99–4259 (USGS, 1999).

Steel, E. L., Davila, A. & McKay, C. P. Abiotic and biotic formation of amino acids in the Enceladus ocean. Astrobiology 17, 862–875 (2017).

Bach, W. Some compositional and kinetic controls on the bioenergetic landscapes in oceanic basement. Front. Microbiol. 7, 107 (2016).

McCollom, T. M. Abiotic methane formation during experimental serpentinization of olivine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13965–13970 (2016).

Cavicchioli, R. Cold-adapted archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 331–343 (2006).

Duboc, P., Schill, N., Menoud, L., Van Gulik, W. & Von Stockar, U. Measurements of sulfur, phosphorus and other ions in microbial biomass: influence on correct determination of elemental composition and degree of reduction. J. Biotechnol. 43, 145–158 (1995).

Cameron, V., Vance, D., Archer, C. & House, C. H. A biomarker based on the stable isotopes of nickel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10944–10948 (2009).

Porco, C. C., Dones, L. & Mitchell, C. Could it be snowing microbes on Enceladus? Assessing conditions in its plume and implications for future missions. Astrobiology 17, 876–901 (2017).

Horita, J. & Berndt, M. E. Abiogenic methane formation and isotopic fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Science 285, 1055–1057 (1999).

Takai, K. et al. Cell proliferation at 122 C and isotopically heavy CH4 production by a hyperthermophilic methanogen under high-pressure cultivation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10949–10954 (2008).

Wang, D. T. et al. Nonequilibrium clumped isotope signals in microbial methane. Science 348, 428 LP–428431 (2015).

Whiticar, M. J. Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. Chem. Geol. 161, 291–314 (1999).

Proskurowski, G. et al. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at lost city hydrothermal field. Science 319, 604–607 (2008).

Etiope, G. & Sherwood Lollar, B. Abiotic methane on earth. Rev. Geophys. 51, 276–299 (2013).

NASA. Enceladus: by the Numbers. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/enceladus/facts (2017).

Glein, C. R., Zolotov, M. Y. & Shock, E. L. Liquid water vs. hydrogen cyanide on Enceladus. In American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, abstract #P23B-1365 (2008).

Sanchez, R. A., Ferbis, J. P. & Orgel, L. E. Studies in prebiodc synthesis: II. Synthesis of purine precursors and amino acids from aqueous hydrogen cyanide. J. Mol. Biol. 30, 223–253 (1967).

Miyakawa, S., James Cleaves, H. & Miller, S. L. The cold origin of life: A. Implications based on the hydrolytic stabilities of hydrogen cyanide and formamide. Orig. Life. Evol. Biosphys. 32, 195–208 (2002).

Roosen, C., Ansorge-Schumacher, M., Mang, T., Leitner, W. & Greiner, L. Gaining pH-control in water/carbon dioxide biphasic systems. Green Chem. 9, 455 (2007).

Postberg, F. et al. Sodium salts in E-ring ice grains from an ocean below the surface of Enceladus. Nature 459, 1–4 (2009).

McCollom, T. M. & Bach, W. Thermodynamic constraints on hydrogen generation during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 856–875 (2009).

Demidova, S. I., Nazarov, M. A., Ntaflos, T. & Brandstätter, F. Possible serpentine relicts in lunar meteorites. Petrology 23, 116–126 (2015).

Kurat, G., Koeberl, C., Presper, T., Brandstätter, F. & Maurette, M. Petrology and geochemistry of Antarctic micrometeorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 3879–3904 (1994).

Lisse, C. M. et al. Comparison of the composition of the tempel 1 ejecta to the dust in Comet C/Hale–Bopp 1995 and YSO HD 100546. ICARUS 187, 69–86 (2007).

Cruikshank, D. P. & Hartmann, W. K. The meteorite-asteroid connection: two olivine-rich asteroids. Science 223, 281–283 (1984).

Buseck, P. R. & Goldstein, J. I. Olivine compositions and cooling rates of pallasitic meteorites. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 80, 2141–2158 (1969).

Chizmadia, L. J., Rubin, A. E. & Wasson, J. T. Mineralogy and petrology of amoeboid olivine inclusions in CO3 chondrites: relationship to parent-body aqueous alteration. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 37, 1781–1796 (2002).

Dodd, R. T. The petrology of chondrules in the sharps meteorite. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 31, 201–227 (1971).

Hua, X. & Buseck, P. R. Fayalite in the Kaba and Mokoia carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 563–578 (1995).

Wogelius, R. A. & Walther, J. V. Olivine dissolution at 25 °C: effects of pH, CO2, and organic acids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 943–954 (1991).

Wogelius, R. A. & Walther, J. V. Olivine dissolution kinetics at near-surface conditions. Chem. Geol. 97, 101–112 (1992).

Daval, D. et al. The effect of silica coatings on the weathering rates of wollastonite (CaSiO3) and forsterite (Mg2SiO4): an apparent paradox? In Water Rock Interaction - WRI-13 Proc. 13th International Conference on Water Rock Interaction (eds Birkle, P. & Torres-Alvarado, I. S.) 713–717 (Taylor & Francis, 2010).

Oelkers, E. H. & Schott, J. An experimental study of enstatite dissolution rates as a function of pH, temperature, and aqueous Mg and Si concentration, and the mechanism of pyroxene/pyroxenoid dissolution. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 1219–1231 (2001).

Knauss, K. G., Nguyen, S. N. & Weed, H. C. Diopside dissolution kinetics as a function of pH, CO2, temperature, and time. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 285–294 (1993).

Golubev, S. V., Pokrovsky, O. S. & Schott, J. Experimental determination of the effect of dissolved CO2 on the dissolution kinetics of Mg and Ca silicates at 25 °C. Chem. Geol. 217, 227–238 (2005).

Bland, P. A. et al. Why aqueous alteration in asteroids was isochemical: high porosity ≠ high permeability. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 287, 559–568 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Barbara Reischl, MSc and Annalisa Abdel Azim, MSc are gratefully acknowledged for expert technical assistance during the closed batch experiments. We thank Dr. Jessica Koslowski for proofreading and comments on the manuscript. R.-S.T. would like to thank Mark Perry and Britney Schmidt for discussions. We also thank David Parkhust for helping with the PHREEQC code and Silas Boye Nissen for his support in the initial attempts of the serpentinization modelling. Financial support was obtained from the Österreichische Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft (FFG) with the Klimafonds Energieforschungprogramm in the frame of the BioHyMe project (grant 853615). R.-S.T. was financed by the University of Vienna (FPF-234) and a fellowship of L’Oréal Österreich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.-S.T., P.P., C.Pr., P.K., and S.K.-M.R.R. performed the experiments. R.-S.T., P.P., S.B., A.H.S., C.Pa., and S.K.-M.R.R. designed the experiments. D.S. and J.Z. designed and performed PHREEQC modelling. W.B. supervised the PHREEQC modelling. R.-S.T., P.P., J.Z., D.S., S.B., A.H.S., A.K., W.B., J.P., C.Pa, M.G.F., C.S., and S.K.-M.R.R. discussed the data. R.-S.T., J.Z., D.S., W.B., J.P., C.S., and S.K.-M.R.R. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.-S.T., P.P., D.S., J.Z., C.Pr., P.K., W.B., J.P., C.Pa., M.F., C.S., and S.K.-M.R.R. declare no competing financial interests. Due to an engagement in the Krajete GmbH, A.H.S., S.B., and A.K. declare competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taubner, RS., Pappenreiter, P., Zwicker, J. et al. Biological methane production under putative Enceladus-like conditions. Nat Commun 9, 748 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02876-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02876-y

This article is cited by

-

Hydrogen storage and geo-methanation in a depleted underground hydrocarbon reservoir

Nature Energy (2024)

-

Sustained and comparative habitability beyond Earth

Nature Astronomy (2023)

-

Life on the Edge: Bioprospecting Extremophiles for Astrobiology

Journal of the Indian Institute of Science (2023)

-

Active lithoautotrophic and methane-oxidizing microbial community in an anoxic, sub-zero, and hypersaline High Arctic spring

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Microbial biosignature preservation in carbonated serpentine from the Samail Ophiolite, Oman

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.